Chapter 3

Craft a Compelling Narrative

Building the Framework to Support Your Message

Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together.

There it begins.

—Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Just as architects must start by first constructing a solid foundation for a building, communicators must begin by creating solid material—the architecture—for their message: the words, facts, and other content that will support their intention and allow them to accomplish their objective. Whether speaking to an audience of one or a crowd of thousands, the first step in the process is gathering and compiling all the pertinent information, creating smooth and logical transitions, and making sure that the material to be delivered will fit into the allotted time.

As any actor knows, you are nothing without strong material. In the theater, the script is the foundation of the performance. And for anyone who thinks a good script isn't important, go watch Robert De Niro in Raging Bull and then watch a clip of him doing an interview while promoting a movie; same brilliant actor, two very different performances—one the result of having strong material and being comfortable and prepared while delivering it, the other out of character and off the cuff. The same is true in a corporate setting: an effective message begins with strong material that not only is well-organized but also supports your intention and objective.

In July 1863, during the height of the American Civil War, General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army clashed with Union forces near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in the battle of Gettysburg. The fighting—the bloodiest of the war—lasted three days and resulted in more than 43,000 casualties. When Lee's army finally retreated, more than 7,600 Americans (some as young as sixteen) lay dead on the blood-soaked battlefield; the scene was horrific. Because of the sheer volume of bodies, most of the dead were simply covered with dirt in the exact spot where they fell.

Weeks later, when Andrew Gregg Curtin, the governor of Pennsylvania, toured the battlefield, the rains had washed away much of the dirt that had covered the bodies. The governor was appalled, believing these brave men deserved a more honorable resting place. He immediately planned for a military cemetery to be constructed on the site to serve as a memorial to the lives lost that terrible day. In four months, the cemetery was finished and a dedication ceremony was planned. The governor needed a powerful figure to deliver the main dedication speech that day so he invited the man who was widely thought of as the best orator in America to deliver the memorial: a man named Edward Everett, a former governor and senator of Massachusetts. Almost as an afterthought, Curtin also extended an invitation to the White House for President Lincoln to say a few words at the event. Lincoln accepted and planned a trip by train to Gettysburg. The president hoped that his presence at the memorial could help ease the pain of his divided country and raise the spirits of the American people. Lincoln, like Everett, was known to give a good speech. An actor himself, Lincoln had refined his oratorical techniques by performing the speeches of Shakespeare for any willing (or unwilling) audience who would listen.1 He also knew how to use his voice and inflection to engage and influence a crowd.

In the weeks before the trip, Lincoln did not get much time to prepare his remarks, though he had an overall idea about what he wanted to say and how he wanted his audience to react. After a sixteen-hour train ride, Lincoln arrived in Gettysburg as the sun was going down. He ate dinner and went to his room to finalize the words he would deliver the following day.

The next morning, a slow parade of men on horseback made its way to the military cemetery where a huge crowd had gathered. A military band played patriotic music and soldiers stood at attention, saluting, as President Lincoln and the procession passed, making their way to the stage. After an opening prayer, Edward Everett took the stage to deliver his dedication address. He spoke of the causes of the war, the war itself, the effect the war had on cities, the soldiers who perished in the fighting, and his hopes for a speedy resolution to the fighting. He spoke of many things … in fact, his speech went on for over two hours—a whopping 13,607 words!

When Everett finished, he took a seat and President Lincoln took his place before the crowd of thousands. He looked out over the battlefield, the very place where those thousands of brave men lost their lives. He saw the faces of those in the crowd as they waited for him to speak, to offer them hope and inspiration. Taking out a paper containing the message that he had carefully crafted, he took a breath and spoke the words that would become so famous: “Four score and seven years ago …”

And in less than three minutes, he was done.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address would go on to be widely acknowledged as one of the greatest speeches of all time, something Harper's Weekly described as “the most perfect piece of American eloquence.” The day after the dedication, Edward Everett, recalling the reaction Lincoln had generated in the crowd that day, wrote to the president, saying, “I wish that I could flatter myself that I had come as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” At only 272 words—a mere three paragraphs—Lincoln's Gettysburg Address is an exercise in economy. His use of powerful word choices, alliteration, and metaphor showed how a simple, well-crafted message with a clear purpose can move the masses and resonate in a nation's collective consciousness for centuries.

Composing Your Message: An Overview

For most people who have to deliver a speech, facilitate a training session, or present material of any kind, there is nothing more unnerving than the blank sheet of paper. The process of beginning can be daunting and even overwhelming, filling one with anxious questions. But unfortunately, thinking is not doing. Eventually you have to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) and begin. As the writer Jack London once remarked, “You can't wait for inspiration; you have to go after it with a club.”

A good place to start?

The two most important factors to focus on when crafting your material are content (what you'll say) and organization (how you'll make the pieces of content fit together into a cohesive and compelling whole). Content comes first. Make a list. What points do you want to cover? What can you read about the subject in preparation? What supporting material will you need? Actually putting your thoughts or ideas onto paper—in any order to start with, you'll organize it later—provides you with clay to start molding.

Once you have your clay—your raw content—you can begin creating a structure for your message. The classic outline structure is unbeatable for organizing not only the order of material but also the relative importance of your points and the relationships among topics and subtopics. An effective presentation, like any good play or movie, needs to have a solid, well-built structure and move smoothly from one topic or section to the next in a logical way. Each point should build upon the point that came before it, and there should be clear transitions between points. Content that is meandering, disjointed, or difficult to follow can frustrate or confuse an audience.

Once you have a rough outline, decide how much time should be allotted for each topic or section, based upon the total amount of time you have for your presentation. Begin fleshing out the outline accordingly, paying attention to both your points and the spaces between them—your introductions, transitions, planned pauses or breaks, and so forth. Over the course of several drafts, you should strive to create a narrative that reflects your personality and feels comfortable and appropriate to both your message and your audience. Above all, bring yourself to the content.

The written word and the spoken word work in different ways; practice reading the material out loud to make sure it is easy to speak. If sentences are too long to be read in one breath, you may need to rewrite them to make them simpler to speak out loud. Read the material through, taking the audience's perspective. Is it clearly organized in a way that will be accessible and interesting to your listeners? While you are the expert when it comes to the content itself, it's crucial that it be organized with your audience in mind. Well-organized material will not only flow more smoothly and make a speaker sound more confident and credible, it will be easier for an audience to follow, easier for them to understand, and ultimately easier for them to remember. With any message you deliver—whether it is a speech to thousands, a meeting with your boss, or a status update to stakeholders—think of yourself as a tour guide, navigating your audience through the information you are there to deliver.

In the next page or two we discuss audience and theme. Basically, these are lenses through which to view your content as you're drafting your presentation. Each will help you focus your material and target your presentation.

Assessing Your Audience

One of the basic rules of effective communication is always know your audience. An audience, whether it consists of one person or one hundred, is a living, breathing entity with specific expectations it is looking to have met. In life and business—just as in the theater—without an audience, communication is impossible. The audience completes the act—as the great Broadway composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim put it, “When the audience comes in, it changes the temperature of what you've written.”2 Without someone listening to what you are saying, you will have no one to buy your products, implement your programs, or pass along your message.

Listen, wait, and be patient. Every shaman knows you have to deal with the fire that's in your audience's eye.

—Ken Kesey

The best way to ensure that your audience listens to you is to first pay attention to them, starting when you are putting the presentation together. What needs are they looking to have met? What do they want? By understanding the expectations of your listeners, you will be prepared to meet or exceed those expectations. And this can only happen with content that both supports your intention and offers a clear benefit to your listeners. When preparing to address a particular audience, answer the following questions, as applicable:

- Who is my audience?

- What is the size of my audience?

- What are the demographics of my audience (age, gender, educational background, religious views, and so on)?

- What is my audience's level of familiarity with my content and topic?

- What are my audience's feelings about my content and topic?

- What are my audience's feelings about me as a speaker?

- What are my audience's goals and expectations?

- What benefit can I offer to my audience?

Every proposal you pitch, every sales call you make, and every meeting you facilitate should be thought of in dramatic terms—like a story. And, like any good story, the message you are communicating should have a hero and a villain. The problem that needs to be solved—that's your villain. (For our organization, Pinnacle Performance Company, boring meetings, forgettable presentations, and ineffective communications are the villains; hence, the tools and techniques taught in our workshops are the heroes.) When approaching your material, ask yourself how you or your company will facilitate positive change for your customer or their organization. How will your product save them time? How will your service make their life easier? Once you identify how you are going to help them, you can use your intention and objective to vanquish the villain (the underlying problem or need) and make yourself (that is, your product or proposal) the hero.

Finding Your Core Theme

What is your presentation about? While assembling your content, it is helpful to identify a core theme for your message and let it serve as a touchstone. Think of your core theme as a distillation of your communication down to its essence, expressed in the form of a headline—a short, compact summary that puts across the main thrust of your message in a single phrase. The core theme you decide upon will guide you to what content you choose to include and how you choose to include it. (Your intention and objective will guide you as well—ask yourself what material you need to include in order for your audience to react the way you want them to react.)

As Dwight D. Eisenhower believed, the core theme of a speaker's message should fit on the inside of a matchbook.3 Most memorable speeches or presentations throughout history can be simplified to a single theme or idea. For example, Steve Jobs unveiling the iPhone (“Apple Reinvents the Phone”), Barack Obama campaigning for president (“Change Is Coming to America”), and George W. Bush launching the war on terrorism (“Either You're with Us or with the Terrorists”). Once chosen, your core theme can serve as a framing device, allowing you to shape and form the intention behind your communication—whether you are a parent reprimanding your child (“Follow the Rules or No Ice Cream”), a human resources director detailing company policies (“Sexual Harassment Will Not Be Tolerated”), or a software sales rep pitching a new product (“Protect Your Data in Three Easy Steps”).

Identifying a core theme can also be helpful when you are presenting or facilitating with others. With your fellow presenters, collectively decide on a core theme: it will inform all aspects of the content and ensure that everyone is telling the same story, employing the same intention, and pursuing the same objective. And since communication is always about providing a benefit to an audience, your core theme should be written from the perspective of the listener, indicating what is in it for them.

The Primacy–Recency Effect

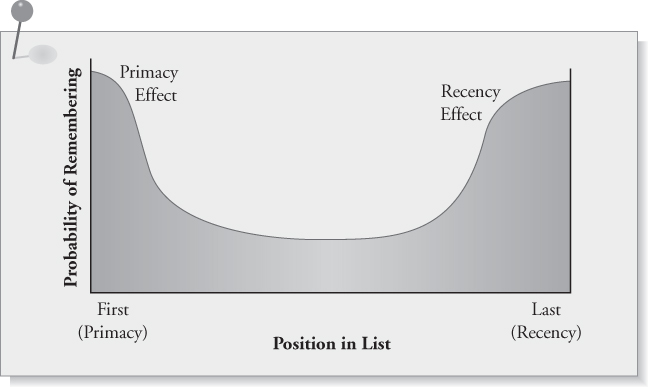

You want your audience to retain the main points of your communication. How you structure it can make a difference to retention. One effective way to do this is to work with what is called the serial position effect, a term coined by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late nineteenth century (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Primacy and Recency.

Source: David A. Sousa, How the Brain Learns, 4th ed. (London: Corwin Press, 2011), p. 95.

Ebbinghaus found that when people take in information, they tend to remember the first and last things they hear, with the content in the middle being the least likely to be recalled. This phenomenon is known in psychological circles as the primacy-recency effect, and it presents a unique challenge for anyone communicating a message, since the meat of a message usually falls smack dab in that middle section.4 But since the ideas or information that stick best for people are what they hear at the beginning and at the end, it is essential that you carefully place your most important content where it is most likely to be remembered (to support this, we discuss the importance of Master Introductions and Master Closings in a few pages). Using a three-part structure of an opening, a main body, and a closing can assist you in doing this—a structure we discuss later in the chapter.

The Rule of Three

The rule of three is a concept in writing that suggests that content or messages delivered in threes is generally more satisfying and effective than content delivered in other numbers. A series of three parallel words, phrases, or clauses—called a tricolon—is a rhetorical device that has been used for centuries by world leaders and great communicators. Three is the smallest number of elements required to create a pattern and it is precisely the combination of pattern and brevity that allows content structured in threes to carry such a punch. It is not by accident that most Hollywood movies employ a classic three-act structure or that some of the most memorable quotes throughout history also follow this simple organizing principle. In fact, the Latin expression omne trium perfectum literally means “everything that comes in three is perfect.”

In Writing Tools, author Roy Peter Clark discusses the rule of three: “The mojo of three offers a greater sense of completeness than four or more.”5 He goes on to explain how and when to use other sets of points for greatest effect: “Use one for power. Use two for comparison, contrast. Use three for completeness, wholeness, roundness. Use four or more to list, inventory, compile, and expand.” In truth, we've all been exposed to the rule of three since we were children. Fairy tales employ the rule of three to teach lessons (think of “Three Blind Mice,” “Three Little Pigs,” and “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”). Good jokes use it as well.

Governor Jon Huntsman, the U.S. Ambassador to China from 2009 to 2011, often uses the rule of three to help simplify his message when negotiating. Asked in an interview why speaking in triplicate was a device he employed so frequently, Huntsman replied: “It's easy to manage, easy to stay on top of, and easy to do.”6 Barack Obama used the progression of three to great effect during his 2009 inaugural address when he said, “We must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America.”

Using the rule of three can be especially helpful to gain commitment or buy-in from an audience. Concluding your message with a call to action that embodies the rule of three leaves no ambiguity about what you seek or what you want from that audience. A group of energy executives whom we trained recently presented a proposal to senior leadership that ended by asking for a significant commitment: an investment of $20 million. To be crystal clear about what they sought at the end of their presentation, these executives used a one-two-three punch in their call to action, concluding, “Gentlemen, we need your buy-in. We need your support. We need your endorsement.”

Repetition is another tool that can be used to help drive your most important points home. By stating a figure or fact more than once, you are signaling to your audience that it is significant and should be given special attention. Winston Churchill, one of the most persuasive communicators in history, praised the value of the rule of three as it related to repetition when he said, “If you have an important point to make, don't try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time—a tremendous whack.”

Mastering Your Transitions

One of the most common reasons that presentations or meetings fail to achieve their desired outcome is that the facilitator or presenter does not have clear and specific transitions; this is usually a result of inadequate preparation. Consequently, everything just blends together in one long blur of data. When crafting your message, it is important to give special attention to how you move from one topic to the next. Think of transitions as little openings and closings—the connective tissue that links the different sections of your content together. The tighter and more efficiently you are able to move from one point to the next, the easier it will be for your audience to stay with you. Without seamless transitions, your message will likely seem choppy or disjointed. Transitions should be clear, smooth, and logical, effortlessly moving your audience from one point or topic to the next.

Try to build every section to a mini climax by using any of the transitional tools described in this section as a button to signal to your audience that one topic is ending and a new one is about to begin. Conversely, once you have buttoned up one section, you then have to start the next session off by capturing your audience's attention through a hook, another device discussed shortly. Effective transitions are often done verbally with words or phrases such as “Moving on …” “Additionally,” and “Turning to …” but can also be signaled nonverbally, through the use of the voice or body. Here are some examples of nonverbal transitions that can be used effectively:

- Movement

- A change in facial expression

- Silence or dramatic pause

- A change in pace

- Variance in pitch

- A change in body posture

- Use of a prop

- Adjustment in volume

- A new visual aid

- Variance in gestures

Structuring Your Message

Certain types of presentations or messages will require more structure than others, for example, when you are teaching a class or demonstrating a process. As you begin to gather and organize your material, don't think of yourself as writing a speech or presentation; think of yourself as preparing one. Once your core theme is set, select material that will support your intention and then assemble it all in a logical order. Just like a good story, almost any message you deliver can be divided into three parts:

- The Opening

- The Main Body

- The Closing

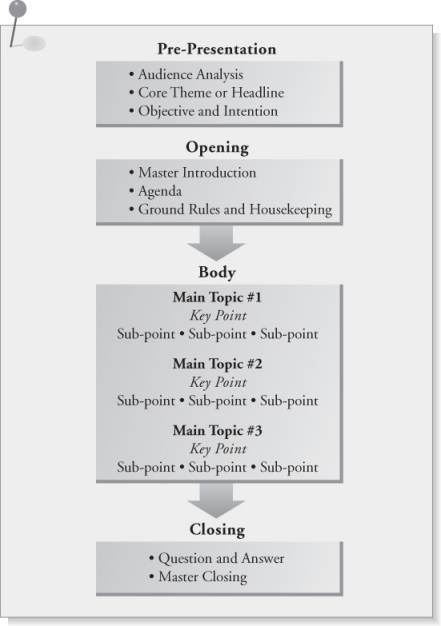

Whether you are asking your boss for a raise, presenting a status update to a team, or seeking commitment from a group of stakeholders, the three-part structure can help you frame your message in a way that is clear and concise. Think of how prosecutors or defense attorneys in court present their case to a jury—both follow a similar three-part structure: an opening statement, the trial itself, then a closing statement. Each of the three sections serves a purpose and helps move your audience in the direction of your intended objective. The flow chart in Figure 3.2 maps a typical business presentation, from the preparatory work to the close.

Figure 3.2 Presentation Flow.

The Opening

The opening of your presentation is where it all begins. This is your chance to make a strong first impression in the eyes of your audience, establish your credibility, and set up what points or topics you will be discussing and what your goals are at the end. The opening is also your opportunity to cover any housekeeping details (frequency of breaks, start and end times, location of rest rooms, and so on), set up your agenda, and establish any ground rules that will need to be followed.

Establishing Your Credibility

If your audience is not aware of your qualifications, the opening would be the place to establish your credibility. If appropriate, include mention of any pertinent degrees, awards, accomplishments, education, experiences, titles, or affiliations that might help establish your bona fides in the eyes of your audience. Unless there's a program for your presentation that contains your biographical information, don't assume that your listeners are aware of your history or accomplishments. Establishing your credibility at the outset compels your audience to listen to what you have to say and give you their full attention.

Using a Hook

In 2003, actor Will Ferrell was invited to give the commencement address at Harvard University, perhaps the most prestigious school in America. As he was introduced, Ferrell entered, dressed in a blue and white yachtsman's uniform (complete with a captain's hat and ascot), dancing to “Celebration” by Kool and the Gang. After a few moments, Ferrell stopped, apparently confused. Feigning embarrassment that he had shown up at the wrong event, he spoke into the microphone. “This is not the Wooster Mass. Boat Show, is it? I'm sorry. I have made a terrible mistake …” This is what we call an effective hook.

A hook is any attention-grabbing device used to capture an audience's interest and compel them to continue listening. As Lyndon Johnson once said, “If they're with you at the takeoff, they'll be with you in the landing.”7 Because of this, try to position a hook as close to the beginning as possible. When considering a hook to include, be creative. People respond to emotion, so you might try to craft an opening that appeals to an audience's heart as well as their head. Surprise them; challenge them; intrigue them. Or as Will Ferrell did, make them laugh.

When the poet Maya Angelou spoke at the funeral of Coretta Scott King, before she uttered a single word, she began by singing the first few lines of a gospel song: I open my mouth to the Lord and I won't turn back, no. I will go, I shall go. I'll see what the end is gonna be. This attention-grabbing opening was so unexpected and moving that the audience in the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church erupted in cheers and applause. At a funeral. Any time you can take your audience by surprise with an opening hook, you increase the odds that they will stick with you for the rest of your message. Examples of potential hooks:

- Stating a problem

- Making a provocative statement

- Sharing an impressive statistic

- Reciting a famous quote

- Asking a thought-provoking question

- Telling a relevant story

- Utilizing a meaningful prop

- Referencing a previous speaker

- Using humor

A warning: Hooks are not all created equal, so be careful when developing yours. A poorly chosen hook can confuse an audience and detract from the message you are attempting to communicate. Test your hook out on others ahead of time and gauge their reaction. Ask yourself: How will it be received by my audience? Does it serve as an appropriate springboard for the message that will follow? Does it logically tie in to the core theme of the material itself?

Presenting a Master Introduction

The purpose of your Master Introduction is to establish the core theme of the message in a way that engages the audience and compels them to listen to you. It should also establish you as a credible messenger and summarize your main points in a way that compellingly introduces the benefit you'll provide the audience. These are the five points that need to be established in an effective Master Introduction:

- Hook or attention grabber

- Name, role, and credibility

- Reason we are here

- Benefit to audience

- Goal at the end of the presentation

Chris Epperly is the director of strategic partnerships with the Country Music Association in Nashville. As part of Chris's role, he frequently has to speak to potential advertisers and promote the CMA brand. His intention and objective are clear: he wants to excite these sponsors so they forge a partnership with the CMA. One of his potential clients was NASCAR. During his preparation for his presentation to NASCAR executives, Chris knew that in order to capture their attention, he would need to begin by crafting an effective Master Introduction. Using the guidelines just provided as a road map, he put together the following Master Introduction:

Thirty-eight NASCAR events over the course of ten months in any given year. Forty-seven million fans. That's a lot, right? Now double that. Ninety-four million—that's how many country music fans there are out there. My name is Chris Epperly and for the past ten years, I have had the privilege of creating strategic partnerships with a lot of corporate American brands, bringing these brands to the Country Music Association. So why are we here? I am here to tell you about our core assets at the CMA as well as why you should be involved in the things we have to offer. What's the benefit to you? Well, that's easy: I want to increase your brand awareness. I want to drive consumer insight and enlighten people as to why your brand is so unique and why the consumer should consider using it. The goal for this presentation is pretty simple: I want to provide you with a unique partnership opportunity with CMA as a whole and then, once we've become partners, I want to drive consumer traffic to your business.

As you can see, Epperly hits all five points of the Master Introduction. He hooks us at the outset with an exciting stat (“Thirty-eight NASCAR events over the course of ten months in any one given year. Forty-seven million fans. That's a lot, right? Now double that. Ninety-four million—that's how many country music fans there are out there”). After his initial hook, Epperly introduces himself, setting up his role and why he should be taken seriously (“My name is Chris Epperly, and for the past ten years I have had the privilege of creating strategic partnerships with a lot of corporate American brands”), before outlining very clearly the overall purpose of the presentation (“I am here to tell you about our core assets at the CMA as well as why you should be involved in the things we have to offer”). Epperly then lays out, in clear terms, exactly what the benefit is to the customer (“I want to increase your brand awareness. I want to drive consumer insight and enlighten people as to why your brand is so unique”) before spelling out his goal at the end of the exchange (“I want to provide you with a unique partnership opportunity … I want to drive consumer traffic to your business”). Because Epperly has included all five points in his Master Introduction, his audience knows exactly who he is, why they should listen, and what's in it for them.

Main Body

Once your opening is completed and you have delivered your Master Introduction, it's time to get into the meat of your presentation. The main body will be the largest section of your presentation. This is your chance to lay out your main points in detail and supply supporting material that backs up your arguments or helps illustrate your points. What are the three or four main topics you will be covering? Once you identify them, you need to expound upon those main topics through key points and sub-points that can illustrate or illuminate what you are attempting to communicate. This can be done through explanations, examples, and facts. Without the inclusion of data and information that support your core theme and explain your main topics, your presentation runs the risk of being nothing more than a series of assertions. There are countless places from which to gather information—books, periodicals, industry surveys, studies, encyclopedias, interviews, video recordings, and organizational websites are just a few examples, as well as internal company documents that are relevant to your topic and appropriate to share. It is also important to give examples or share anecdotes that link to your listeners' experiences; this will help them understand and retain the information you are discussing.

This is the part of your presentation where you might choose to use supporting material to help clarify, justify, or emphasize the points you are trying to make. This could include data, statistics, charts, graphs, quotes, video or audio clips, photographs, testimony, or anecdotes. As you consider specific supporting material to include, ask yourself the following questions, and only use the material if the answers are all yes.

- Are your statistics accurate?

- Are your sources reliable?

- Are you using the statistics correctly?

- Do your statistics support your points and intention?

Oral presentations are not the same as written presentations. As you create the text for your content, write in a tone that is conversational, as if you are speaking to a friend. Try to avoid long, run-on sentences. These are hard to speak and difficult for an audience to follow and comprehend. Keep your phrasing simple. A good way to test out your text is to read it out loud. Are your phrases and sentences easy to say? Do you use words likely to show up in an informal conversation? If you find yourself tripping or stumbling over words or running out of breath before you reach the end of a sentence or phrase, these are the sections you might want to go back and rewrite.

The information you don't include in your content is often just as important as the information you do include. A good speech or presentation cannot just be a data dump. Less is almost always more, so thoughtfully restrict the information you choose to include. Leonardo da Vinci once said, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” Or, as Steve Jobs put it in an interview with Businessweek, “Simple can be harder than complex: You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it's worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains.”8

William Henry Harrison, the ninth president of the United States, learned this lesson the hard way. On March 4,1841, while standing outside in the freezing cold, Harrison gave the longest inaugural address of any president in U.S. history—lasting 105 minutes! As a result of the speech being so long (and because Harrison was sick and refused to dress appropriately for the event), he ended up coming down with pneumonia and died a few weeks later, making him the shortest serving president in history and the first president to die while in office. Perhaps President Harrison could have benefited from the advice of actor and comedian George Burns, who often joked that the secret to a good speech was “to have a good beginning and a good ending, then having the two as close together as possible.”9

Too often, presenters don't take the time to properly edit their material and, as a result, they waste their audience's time with redundant or unnecessary content. Honor your audience by reducing your content to only the essential information needed to make your points and achieve your objective. Editing is the art of synthesizing your material down to the minimum needed to communicate your message. Winston Churchill understood the importance of honing and refining content. After delivering one rather lengthy address, he was reported to have remarked: “I must apologize for making a rather long speech this morning. I didn't have time to prepare a short one.” Another reason to limit the amount of content you attempt to communicate is that the human short-term memory can only process so much information. Including too much can be overwhelming to an audience and can result in their missing the main points you are trying to make.

In 1956, psychologist George A. Miller published a paper titled “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” in The Psychological Review.10 The paper presented the concept of “chunking” as it related to the average person's ability to process and remember data, facts, or information. What Miller found in his studies was that people are only able to hold between five and nine separate pieces or “chunks” of information in any meaningful way—with the “magic number” being seven. (A good example of this is the “I'm going on a camping trip” game we played as children. Seldom does the game progress much past nine items before people start to get eliminated.) As Miller's study suggested, working memory can only retain so much information, so it is helpful to limit the main points of your message to around seven, and then illustrate those points through the use of supporting material. By limiting your content to seven points or fewer, you help your audience more clearly understand how each point links to your overall theme. A person of few words needs to make those words count, so choose carefully.

Miller's theory should extend to any PowerPoint slides you choose to create as well. For slides, we recommend you follow what we call the “statute of six,” meaning no more than six word slides in a row (break them up with a graph, diagram, or photo), no more than six bullets per slide, no more than six words per bullet, and (most important), the main message or essence of your slide should be easily understood in six seconds or less. For excellent examples of visual aid use, watch Al Gore in An Inconvenient Truth or any product launch by Steve Jobs.

Closing

After completing the main body of your presentation and taking questions, it is time to wrap things up. The goal is to end your presentation with impact so the audience is able to walk away remembering exactly what you wanted them to remember. Make sure that you take time to summarize what you have previously told them and drive home your key points one last time.

Creating a Master Closing

Just as your Master Introduction framed your message at the outset, you need a Master Closing to revisit those points and reframe the message for your listeners at the end. Here are the five points that should be included with your Master Closing:

- Summary of main points

- Review of benefit to audience

- Reintroduce the goal and ask for action

- Closing hook or challenge

- Thank-you to audience for time

We used the example earlier in this chapter of a Master Introduction done by Chris Epperly from the Country Music Association to the NASCAR executives. At the end of his presentation, Epperly's Master Closing might look something like this:

So I've provided quite a bit of detail today about the CMA brand as a whole and all of the exciting assets we could make available to you if you choose to join with us as a strategic partner. If you do decide to align yourself with all that the CMA has to offer, I am confident that we will be able to increase your brand awareness and, ultimately, drive consumer insight, showing people exactly why your brand is so unique. To put it plainly: it will increase your business. The goal I laid out at the top of this presentation was to provide you with a unique partnership opportunity. I've detailed why I believe a partnership with the CMA would drive consumer traffic to your business. The ball is in your court now. As Henry Ford once said, “Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.” Thank you very much for your time. I look forward to your decision.

Again, following the road map of an effective Master Closing, Epperly summarizes his main points (“I've provided quite a bit of detail today about the CMA brand as a whole and all of the exciting assets we could make available to you”) and then reminds the audience of the benefit (“increase your brand awareness and, ultimately, drive consumer insight”). He tells them again what he wants to come from the presentation (“provide you with a unique partnership opportunity … drive consumer traffic to your business”) and before thanking them, ends with a closing hook (Ford quote) and challenge (“The ball is in your court”). Because Epperly made sure to incorporate all five points in his Master Closing, the conclusion of his presentation and the purpose of his overall message are clear and unequivocal.

Rhetorical Tools and Techniques

This section presents a number of rhetorical tools that can help you keep your audience engaged, illustrate a point or idea, and make the information you are providing stick in their memory. Try to think of times when you have used these in your own communication and try to recognize how others—politicians, coaches, broadcasters, or executives—have used them effectively when delivering their message.

Signposts

Signposts are brief previews, usually in the form of a short list, that let your audience know where you are headed and help them organize the ideas or concepts you are discussing. Think of each signpost as a little road sign for your audience as they travel down the highway that is your presentation. Since your audience will rarely have a hard copy of your presentation, signposting helps them organize your points mentally for better comprehension and retention—simply put, signposts can help your listeners stay with you by providing them a road map. Examples of signposting:

Spotlights

Spotlights are used to give special focus to a specific fact or detail in your presentation. Think of this technique as suddenly shining a bright light on a particular piece of information that you want your audience to remember or give special attention to. Examples of spotlighting:

Another way to use spotlighting effectively is to repeat a specific word or phrase to give it emphasis in the eyes of your audience. For example:

When tasked with presenting slides or other visual aids that contain too much content or overly technical information, spotlighting can be used effectively to boil the content down to something the audience can absorb. For example:

Teasers

Teasers are used to give your audience a peek into something—a topic or subject—that will be coming up later in your presentation. This will serve to pique their interest enough that they will stay with you as you take them along on the journey that is your presentation. Be careful not to give them too much information. Make sure it is just enough to whet their appetite so they want to hear more and stay with you all the way. Think of movie trailers and how they show you just a few exciting scenes from a movie. If the trailer is good, it will show just enough to hook people so that they will want to see the entire movie. In fact, according to world-renowned anthropologist Dr. Helen Fisher, when we are teased with some information and left with a bit of mystery it actually triggers the flow of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that provides a natural high.11

Examples of teasers:

At a recent conference in San Diego one speaker used a teaser quite effectively. The main topic of his particular session was “The Ten Secrets of Effective Time Management.” Over the course of his one-hour session, this polished and compelling speaker discussed the first five secrets to an audience that was clearly engaged with his content and delivery. As the one-hour mark approached, the speaker smiled and remarked, “As you might have noticed, I have only given you five of the ten secrets and we are, unfortunately, out of time.” The audience groaned with disappointment. “Well, fear not, friends,” smiled the presenter. “It is not my intention to leave you hanging here. What we have done, is we have placed a secret link on the homepage of our website.” He then flashed a slide containing his company's website and instructions for accessing the secret link. “Go to our website and click on that secret link. It will take you to a page containing the final five secrets to effective time management.” Do you think the vast majority of that audience went to the secret link to get those remaining five tips? Of course they did! Not only did this speaker surprise his audience with the secret link, he created a teaser that actually drove traffic to his company's website!

Callbacks

This is a technique often used by comedians—they “call back” to a joke they told earlier in the set, often in a different context. Presenters can use them too, mentioning something from earlier in the presentation to reiterate a point or draw a comparison. Not only does it help create familiarity and rapport with an audience, it also helps to reinforce any important points that you want your audience to take away and remember. Examples of callbacks:

Metaphor and Simile

A metaphor is a figure of speech that uses one thing to mean another in order to make a comparison between the two, often unrelated, things. Examples would be Shakespeare's “All the world's a stage”; “The torch has been passed” in John F. Kennedy's inaugural address; or simply referring to someone who does well at something as having “hit a home run.” A simile is a form of metaphor that uses the words “like” or “as” to compare two different things to create a new meaning. “They fought like cats and dogs,” “A ruby as red as blood,” and “She laughs like a hyena” are all examples of simile. Sprinkled strategically throughout your delivery, metaphors and similes can be powerful tools to connect with an audience and communicate points quickly and effectively. Of course, the various parts of your metaphor must be drawn from the same realm of experience. “Hit a home run” is clear, but “hit a home run right through the goal posts” is confusing and thus ineffective.

When crafting and organizing the content for your meeting or presentation, return frequently to the structure elements and rhetorical tools discussed in this chapter. Try to include as many of them as possible. Experiment with some you use less frequently. Surprise yourself. Creating solid material takes time and effort. By putting in the necessary hours and carefully constructing your content with an eye toward your overall intention and objective, you not only demonstrate a respect and appreciation for your audience, you also give yourself a launching pad from which to begin preparing your delivery.