Chapter 1

Understand the Secrets of Persuasion

Communicating with Intention and Objective

The starting point of all achievement is desire.

—Napoleon Hill

We've all seen or heard persuasive speakers—people who engage us with their communication effectively, whatever its subject may be. And because they are able to capture our attention (and perhaps our imagination), the chances are good that they will also be able to move us emotionally or change the way we think about a topic or issue. But how exactly do they do it? What makes someone persuasive as a communicator?

The story of one of history's most famously persuasive speakers gives us some insight.

Often regarded as the greatest of Greek orators, Demosthenes, the Athenian statesman and rhetorician, rallied the citizens of Athens against the military power of Philip of Macedon and Philip's son, Alexander the Great, for almost thirty years. So powerful was Demosthenes in his ability to rouse the passions of his audiences that Cicero (perhaps the greatest Roman orator) called him “the perfect orator.”

But Demosthenes, who was the son of a wealthy sword maker and was orphaned at age seven, was not always celebrated for his abilities—in fact, his early attempts at speaking were met with ridicule.

In ancient Greece, public speaking was a vital aspect of everyday life, and skilled orators or rhetoricians were valued very highly. When he was still a boy, Demosthenes saw some of the great rhetoricians of the day speaking in court or in the assembly—a regular meeting of the citizenry, where they would deliberate and vote on all aspects of Athenian life. He was captivated by their power and popularity, and set about to study their methods and become a great orator himself.

He had some early success in court, bringing suit against his guardians for mishandling his estate. But his first efforts in the assembly were met with jeers and derision—his style was stilted, his sentences tortuously long, his voice weak and breathy. People hated listening to him. Crushed by this public humiliation, Demosthenes fled the assembly in shame.

On another day, when Demosthenes had not been allowed to speak before the assembly at all, he came upon an acquaintance—an actor named Satyrus. It's not fair, Demosthenes said. I work hard on my speeches; I'm far better prepared than any of those idiots they let speak, and they won't even listen to a word. Satyrus, as a professional actor, perfectly understood the cause of Demosthenes' failure in the assembly: the problem was not his message—it was the poor delivery of his message. Demosthenes' speeches failed to connect with his audience because they lacked something vital—they lacked intention. The young orator took no care in how he came across to his audience—he didn't even seem to know he should—and as a result he thoroughly alienated the people he meant to persuade.

To demonstrate the problem, Satyrus had Demosthenes read a passage from the classics, and then he read it himself, using his voice and body with all his skill. Demosthenes was thunderstruck—the passage seemed like an entirely different text when the actor read it—and from that day he began to believe that if a speaker neglected his presentation, he might as well not speak at all. He saw that a speaker's intention—the choice to act and speak persuasively—was imperative and essential to his objective—to persuade.

Demosthenes took to the actor's teaching with a vengeance. He built an underground chamber—a sort of cave—and he practiced his gestures and intonation there every single day. He picked apart speeches—his own and others'—rephrasing what was said more gracefully and practicing it aloud in his chamber. He trained his breathing by reciting a speech while running or climbing. He put pebbles in his mouth to improve his enunciation. He rehearsed in front of a mirror to check how his posture, gestures, and other body language would come across to his audience.

When it was time for Demosthenes to speak in front of the assembly again, all of Athens took notice. His fiery speeches about the political, social, and economic issues of the day riveted, persuaded, and roused the Greek citizenry. Neither his subject matter nor his audience had changed, nor had his objective—to compel his listeners to action. But once he began delivering his speeches with intention—and with an actor's techniques—the results could not have been more different.

Intention and Objective

The Pinnacle Method, adapting the actor's approach to a wide range of communications, is based on the simple premise that whether you are making a customer service call, delivering a large presentation, running a team meeting, or having dinner with your family, the success of your communication depends upon two things. First, you must identify an objective—something you want or need from your audience. And second, you must choose an intention that will assist you in the pursuit of that objective. Think of the objective and intention in your communication like this:

- Objective = What You Want

- Intention = How You Are Going to Get It

Actors, by training, know the secrets of objective and intention and how to make them work together for effective communication.

It's a common misconception that actors pretend to be other people. In reality that's not what we do at all. Rather, we are trained to put ourselves—our true selves—into imaginary circumstances and deliver our message (in this case, our lines) with a specific intention to generate a desired reaction from our audience (whether that audience is our scene partner or the audience who paid to come and see us). We need our audience to believe what we are saying as the character in that moment. If they don't believe what we say, the credibility of our character comes into question, and the success of our performance is compromised.

The same can be said for any person's communication. If we don't believe what someone is saying—whether that person is a salesman, a mayoral candidate, or our teenage daughter—they end up communicating to us something different from what they intended—for example, we come to believe that this product is actually not a good fit for our needs; that these policies don't sound very effective; or that perhaps we should check to see if her homework is really done.

All of these people in the examples above want something that depends on us, their audience—a sale, a win, a trip to the mall—and they want to compel us to do something—buy the product, vote for them, give them permission to go. If their objective and intention are not well aligned, we'll remain unconvinced, their communication will have failed, and they won't get what they wanted.

Thus an objective, if properly aligned with intention, should result in a successful communication—one that changes your audience's knowledge, attitude, or action with regard to the topic being discussed or presented. As a communicator, you must have a specific objective in mind—something you need to accomplish—if you hope to impact and move your audience. In the end, without an activated intention behind your delivery—and one that is specifically in line with your objective—the best your message will be is ambiguous. A strong intention behind your words will literally fuel the emotion of your delivery.

In the rest of this chapter, we show you how to clearly identify a specific objective for your communication—to understand exactly what you want to have happen as a result of your message. We also guide you in the process of pinpointing and choosing the most effective intention to accomplish it.

For your communication to achieve its objective, all aspects of your delivery must be supported and driven by the chosen intention. It is the ability to combine these two elements working in tandem that separates engaging communicators from those who fail to engage an audience in any meaningful way.

Defining Your Objective

As Demosthenes discovered, effective communication never consists of words alone. There must be a purpose behind those words that calls an audience to action. The result of this action is, ideally, identical to what we call a communicator's objective. Simply put, your objective is the goal or purpose you hope to achieve with your audience as a result of the delivery of your message. A computer sales rep wants to sell a computer, a teacher wants the students to learn their state capitals, and a safety manager wants the workers to avoid injury.

Constantin Stanislavski, the founder of the Moscow Art Theatre in the late nineteenth century and the father of modern acting, wrote extensively on the concept of objective in his groundbreaking book An Actor Prepares.1 In his books and methods, Stanislavski developed an approach to realistic acting that is still used to this day. One of the major precepts of the Stanislavski system was the importance of a particular kind of preparation. An actor was to begin by studying the script and identifying goals and objectives for every scene, seeking answers to the following questions:

By carefully and thoroughly answering these three questions, actors gain a much clearer idea of what they want to accomplish in a particular scene. The questions are so effective that they have come to represent a sort of “holy trinity” for actors.

But they can just as easily be applied to communication in any setting—whether you're managing a team, hoping to influence a stakeholder, or asking someone out on a date. As Stanislavski explains, “Life, people, circumstances … constantly put up barriers … Each of these barriers presents us with the objective of getting through it….2 Every one of the objectives you have chosen … calls for some degree of action.”3

But not all objectives are created equal, and most communication doesn't consist of just one objective; instead, it comprises numerous objectives—smaller goals that need to be achieved in order to accomplish the main one. Your most important objective, the one that best describes your overall goal, Stanislavski called a super-objective. For example, a teacher's super-objective might be to teach the students geometry, but first they must be induced to take their seats and be quiet.

Before delivering any message, you need to understand what you want at the end of your communication. What is your super-objective? Is it buy-in from the other party, or commitment for more funding, or additional personnel? Is it a signature on a contract or the adoption of a new policy? Whatever the goal is for your communication, you need to clearly understand it for yourself. Otherwise you risk being like a marathoner who runs and runs but has no idea where the finish line is. Write it down, using concrete language. If you have more than one objective, express each clearly and concretely.

Once you know your objective you have half of what you need to communicate effectively. The other half is the communicator's secret weapon and most invaluable tool—intention.

Choosing an Intention

Often when we develop a message, we focus primarily on the words and content we are delivering. We usually also have an objective in mind, of course, even if we have not defined it carefully and precisely. What we often fail to ask ourselves is why that overall message should be important to our audience. Why should they care? What would make them care? We neglect to pair intention with objective. This very common mistake is usually fatal to effective communication.

Before delivering their messages, communicators must understand with great clarity how they want their audience to react to each message. How do they want their audience to feel as a result of their communication? The answer to this question is the speaker's intention; according to the dictionary, intention is “an aim that guides action.”

Understanding the importance of intention and deploying it effectively is the cornerstone of brilliant acting, often separating a memorable performance from a forgettable one. Actors use intention in every aspect of their performance, breaking down each moment of a scene to understand their objective and help them identify the specific intentions they will use to deliver their lines. Actors always have an objective in a scene, something they want (to get the money, to sleep with the girl, to convince the bully to stop picking on them) and they always pair that objective with a complementary intention. They use their intentions to threaten, seduce, or intimidate to accomplish the objective. While actors focus their intention and objective on their partner in a scene, there is always another audience at play in the theater: the people sitting in the dark watching the action on stage. The director's job is to make sure that the intentions of the actors on stage are strong and specific so they have the effect of bringing the other (theatrical) audience along, ensuring that they feel the appropriate emotions at the appropriate times. And as circumstances in a scene change, an actor's objectives and intentions will change as well. As a communicator, you'll find intention the most powerful tool in your arsenal too. It will not only bring passion and purpose to your message, it is the most critical component in the pursuit of your objective—the rocket fuel that will launch you toward the eventual accomplishment of your goal.

In Tell to Win, Hollywood producer and former chairman of Sony Pictures Peter Guber writes that capturing your audience's attention “involves focusing your whole being on your intent to achieve your purpose…. Your intention is actually what signals listeners to pay attention.”4 In other words, without a strong intention supporting your delivery, your audience is less likely to give you their attention in the first place. And that's just the first benefit a strong intention brings to your attempts to communicate. It also holds the audience's attention, and the passion and purpose it conveys actually bring the audience members into sympathy with your point, so that they are connecting both emotionally and intellectually with your message.

Dan Siegel, a UCLA neuroscientist and author of The Mindful Brain, has discovered that a listener's mirror neurons only switch on when they sense another person is acting with passion and purpose. Everything people do with their voice or their body communicates information to a listener or audience. For this reason, Siegel states that people such as teachers or instructors “need to be aware of their intentions … to make the experience of learning as meaningful and as engaging as possible…. In return, [the students or audience] will feel inspired and engaged in the passion of the work.”5 Humans begin reading each other's intention cues as soon as they are physically close enough to see, hear, or smell them. Says Siegel, “With the attention to intention we develop an integrated state of coherence.”6 This is precisely why all aspects of a person's communication and delivery must be in sync. The cues your face, voice, and body send are so powerful that your audience will pay attention to them before anything else; thus an intention that's out of sync with the content of your message or your desired objective will torpedo your communication.

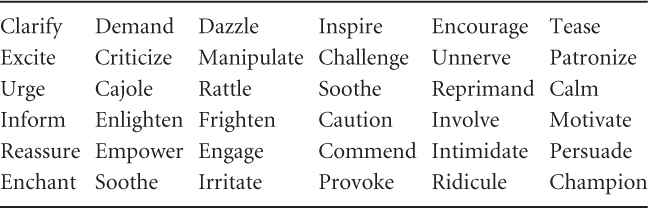

When you're identifying your intention, express it as a verb—a strong action word that can activate and inform your delivery. For example, your intention might be to inspire your employees to act in a certain way, or to reassure a colleague that a decision was correct. Here are a few examples of different intentions commonly used during the average person's daily communication:

Think of a recent interaction with someone where you tried to convey one of the intentions in the list. Did your physical and vocal delivery support your intention so effectively that your listeners knew exactly how you wanted them to feel? A strong intention, activated properly, will inform all aspects of one's communication—body language, facial expressions, vocal dynamics, and all the rest. To experience how this works, try this: using the list of intentions provided previously, say the phrase, “Can I see you in my office?” five different times, each time reflecting a different intention. You will notice how the delivery of the words changes as your intention does.

Putting Intention and Objective into Practice

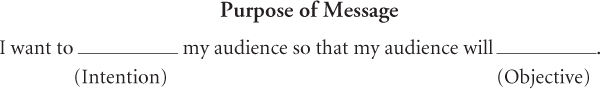

The famous acting teacher Uta Hagen writes in her seminal book Respect for Acting, “The action of the words, how I will send them, for what purpose and to whom, under what circumstances, hinges solely on what I want or need at the moment.”7 What she is speaking about here is the combination of intention and objective. When identifying the intention and objective, you should be able to describe the purpose of your message in a single sentence:

Here are a few examples of different communication scenarios to illustrate the point:

Intention and Objective: I want to warn my employees about their unsafe behavior so they comply with safety policies and avoid injuries.

Intention and Objective: I want to commend my staff and volunteers for their great work in this campaign so they feel appreciated and validated.

Intention and Objective: I want to motivate my daughter so she applies herself and studies harder.

Intention and Objective: I want to caution these new cashiers about their personal conduct so they understand company policy and don't commit employee theft.

Intention and Objective: I want to persuade this homemaker about the superiority of this vacuum cleaner so she places an order for purchase.

In any communication, it is helpful to imagine that your intention is connected to a human emotion you hope to access in your audience. Imagine how you want your audience to feel as a result of hearing the words you will be saying. Remember, it is always about your audience and how you want them to feel about your material or message; it is never about how you feel. You might find the material boring. You might not feel connected to or enthusiastic about your company's product or offering. In fact, you may not even agree with the program you are required to speak about or the subject you are assigned to teach. In the end, the fact that you are not engaged with your material is irrelevant because, as a communicator, it is never about you: it is always about your audience. You must choose an intention that makes your audience react the way you need them to react (we discuss using your voice effectively in Chapter Six). For example, if you want new employees to feel welcome, smile when you are introducing them to the team and use the various aspects of your voice (something else discussed in later chapters) to express your enthusiasm. If you are disciplining a child for breaking a vase, use stern facial expressions and direct eye contact to communicate the seriousness of the situation.

We all know what it means to truly have an objective. To get him or her into bed, to get the job, to get out of mowing the lawn, to borrow the family car. We know what we want, and, therefore, we know whether we're getting closer to it or not, and we alter our plans accordingly. This is what makes a person with an objective alive: they have to take their attention off themselves and put it on the person they want something from.

—David Mamet

Often we are tasked with presenting material or a message that might be dry or dull. This is a case when intention and objective are particularly valuable tools in your communication arsenal. Even though you may not personally find the topic or content interesting or exciting, you still need to understand why that information is important to your audience, and you still have to deliver the information with meaning. (Delivering financial numbers or technical data can be especially challenging, both from your perspective as the speaker and from your audience's perspective. This is a case where it becomes vital to clearly understand why the information you are providing is important to the audience and what you hope to achieve by conveying it to them.)

Regardless of the content of your message, you want your listeners to be emotionally engaged, and you want their investment in what you are saying. You may or may not be emotionally engaged or invested in your message; that's not the point. You can still communicate effectively if you choose your intentions wisely. Let's see how that works in practice.

Intention Cues

So, to review: for your communication to have impact, you first must decide how you want your audience to act upon your message (your objective); then you need to pinpoint an intention to deliver that message in order to best achieve that action. Finally, you must activate what are known as your intention cues—the vocal and physical manifestations of your intention—to ensure the words and delivery match up and the message achieves the desired result with your audience.

As mentioned previously and as we return to in later chapters, everything you do with your voice and body must support your intention. When all of your vocal and physical cues are in sync with your chosen intention, this is called congruence. When you offer mixed signals, or there is a disconnect between what you are saying and how you are saying it, your audience can become confused or distracted. This is called incongruence and it is the enemy of effective communication.

For instance, if a doctor's intention is to convince a patient to eat a healthier diet, his intention cues would have to reflect that. Depending on the patient, cues might include a serious facial expression, direct eye contact, and a warm but serious tone of voice. Other signals such as rushed speech, flickering eye contact, or attention to the file or the clock rather than the patient can convey a lack of seriousness or concern and lead the patient to tune out the message.

Let's try another example. The stereotype of a used car salesman is of someone who communicates in a pushy or dishonest way. Of course, in reality, there are good used car salesmen and bad used car salesmen. Any used car salesman has an objective: he wants to sell you a car. But his intention cannot be the same as his objective. If his intention is to sell, then everything he does with his body language and vocal cues would signal “selling,” and this would be a turn-off for a potential customer. For the salesman to sell that car effectively, he needs to think not about selling but about the feelings he wants to elicit in his audience—trust, reassurance, and excitement. That's his message: “I see what you want in a car; this is a good car that I feel proud to have in inventory; you'll feel good owning it.” Not “I want to sell you this car”—never that. He has to convey his intention through the way he uses his body and voice—a smile and open posture, attentive facial expression when the buyer is talking, quiet excitement in his voice and gestures when he is showing off the car's features. The buyer needs to feel persuaded or excited about purchasing that car for the salesman to achieve his objective and, in the end, make that sale. But the way the salesman achieves his objective is to turn his back on it, so to speak, and immerse himself in his intention—how he wants to make his audience feel.

In whatever position you find yourself, determine first your objective.

—Ferdinand Foch

Once you understand your objective and intention, you can become aware of how your intention cues get your audience to react the way you want. By shouting, you will get a room of children to be quiet; by waving your arms wildly you will get the attention of the lifeguard; by smiling at your coworkers you will let them know you are happy to see them. In Chapters Five and Six we talk more about intention cues and how to best deliver your message, both vocally and physically.

Primary and Secondary Intentions

Just as an actor might identify various intentions throughout a scene, someone presenting in a corporate environment will most likely move through different intentions over the course of a speech or presentation. We call these primary and secondary intentions. The primary intention will be your main intention and the one that connects most directly to your super-objective, while secondary intentions are no less important but shift according to the smaller objectives you move through in the course of the presentation. You might think of the primary intention and the super-objective in terms of strategy, while your secondary intentions and objectives are tactics in support of that strategy.

As a speaker moves from one intention to the next, noticeable changes should take place in eye contact, facial expressions, vocal aspects, and body language to help signify and communicate that change to the audience. Each of these transitions from one intention to the next must be clear. For example, the intention at the opening of your presentation might be to welcome your audience, but could shift to reassure as you begin presenting industry trends, and then to excite as you unveil the new product you will be launching. Actors call these transitions that move you from moment to moment beats, the term used by Stanislavski at the Moscow Art Theatre, where actors were trained to break up their scenes into smaller sections.

Every communication you deliver will include various intentions and objectives. Understanding what you want and how you are going to get it is important whether the communication is in a formal business setting or happens more informally over drinks with friends. If the message you are delivering is in the form of a speech or presentation, you may take advantage of the format (which is prepared in advance to the point of written notes or talking points, an outline, or a full manuscript) to practice breaking your message down into beats. Actors do this when they mark up their scripts, physically marking or coding each section by intention and objective.

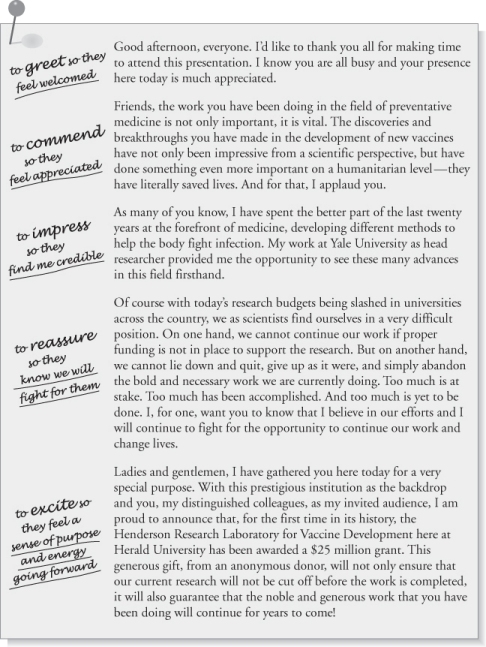

Take a look at the speech in Figure 1.1 as an example. As you can see, the speaker has coded the text of the speech by identifying the intentions to be applied throughout, paired with their corresponding objectives.

Figure 1.1 Speech Markup.

Each of the first four paired intentions and objectives works in the service of the final set of primary intention (excite) and objective (make the listeners feel good about the organization and their work).

The How of Intention Cues

As the speaker who codes beats in advance will clearly understand, identifying the objective and activating the proper intention in each section of the message will help the audience understand how they should feel about the material or information they are receiving.

So how would someone delivering the speech in Figure 1.1 activate the intention cues throughout the actual delivery? Simple: by playing the circumstances and intentions of only one section at a time. For example, the first section (to greet) will require a smile to support the message and appear genuine. The next section (to commend) would probably benefit from continued smiling, enthusiasm in the voice, and the prompting of applause from the audience to make people feel appreciated and valued. The next sections (to impress and reassure) get more serious, so the tone of voice will need to reflect this as well. And seriousness doesn't require a smile here, so that can fade for the moment. Finally, as the speaker moves to the main point of the message and the big finish (to excite), the task would be to build the energy of the delivery by modulating volume, pace, gesture, and facial expression so that the audience clearly understands what this new information means to them and exactly how they should feel about it.

It may all seem a lot to consider, and it is. But the ability to identify super-objective and primary intention, the process of breaking a whole message down into beats of paired objective and intention, and the practice of simply concentrating on one beat at a time, makes the effective delivery of even the most complex communication not only possible but even easy.

As you begin to consider your own individual communication and how you can start to incorporate an awareness of intention and objective into it, understand this: once your objective and intention are engaged, these two elements will often do your communication work for you. If you can generate a genuine feeling or emotion inside, it will be reflected in what others see and hear. But this cannot happen without your choosing and activating a specific intention and objective.

To impact or influence your audience you must have clarity and purpose in your message, and this can only happen through identifying an objective for your communication and then activating the specific intention (or intentions) that will move you toward it and result in your audience reacting the way you want them to react.