LESSON 6

Adversity Is an Opportunity

I think that the only true disability is a crushed spirit; a spirit that’s been crushed doesn’t have hope, it doesn’t see beauty, it no longer has our natural, childlike curiosity and our innate ability to imagine.

—AIMEE MULLINS

It may seem hard to believe, but it’s catastrophe that offers the most promise for an even richer life. This is the gateway to the good stuff. In other words, you never truly know which way the wind is blowing until the shit hits the fan.

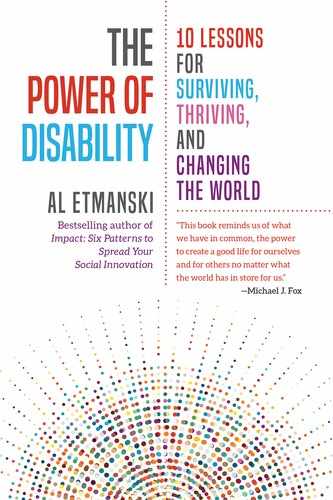

—MICHAEL J. FOX

What Sam Sullivan Taught Me

What Sam Sullivan Taught Me

MANY OF THE world’s most enduring advances have come from people whose love in the face of adversity was so strong that they had no choice but to rise again. And again and again.

If Sam Sullivan hadn’t decided to get into politics, he could have become the king of gizmos. (He defines gizmos as one-of-a-kind customized devices and gadgets that make life easier for people with disabilities.) Instead he became mayor of Vancouver. He remains a well-known British Columbia politician.1 Sullivan’s inventiveness emerged out of darkness. He broke his neck in a skiing accident at the age of nineteen. All the things that had meant so much to him, like music and sports, no longer seemed possible. He struggled with depression for years. In the depths of his despair he considered ending it all. As he played out the details in his mind, he found himself thinking of those he loved, particularly his young niece. By coincidence, she visited him the next day, greeting him with her usual “Hi, Uncle Sam!” It was a watershed moment. He decided to stop thinking about what he was missing and to live his life with gusto. He resolved to do whatever was necessary to make that happen. What started as self-preservation led to breakthroughs that have spread far and wide, affecting people inside and outside the world of disability.

Traveling with Sullivan always turns me into an apprentice. I remember one road trip from Vancouver to Oakland, California, to visit Jerry Brown when he was mayor of the city. It was an exercise in collecting the scraps of paper that Sullivan doodled on. Or scribbling on scraps to write down another one of his bright ideas. Sullivan can’t help himself. He’s a modern-day Leonardo da Vinci. Ever curious, he is constantly thinking of ways to eliminate the barriers that prevent people from getting to know each other and helping each other out.

His innovations include a suite of organizations to assist people with spinal cord injuries who want to fly ultralights, play and record music in a fully accessible studio (he named his own band Spinal Chord), sail boats simply by sipping and puffing with their mouths, and garden at wheelchair height. He also helped invent the TrailRider, a one-wheeled vehicle that enables people with spinal cord injuries to travel in the backcountry. It’s been used to reach the base camp of Mount Everest. Sullivan’s ingenuity lives on in the Tetra Society, which has unleashed a network of gizmo inventors across North America. It matches volunteer engineers, technicians, and designers to people with disabilities who have an accessibility challenge. He also played a leadership role in generating public support for the first safe injection site in North America, a decade before anywhere else, and established a “greeting fluency” initiative to teach people how to greet people from other cultures in their own languages.

Adversity can be our teacher if we let it. And why shouldn’t we? Sooner or later, it will find us. And we have to decide what to do with it. Conquer it? Hide from it? Fight it? Leave it to others? Often we have no choice but to accept it. Acceptance isn’t resignation or giving in. It’s an acknowledgment of reality, of what exists. Acceptance gives us a base to begin figuring out what to do next. Adversity appears in a variety of forms: accident, loss, hardship, cruelty, destruction. Whether it happens to us or to someone or something we love, the suffering and pain is deeply personal, at times unbearable. Grief, anger, fear, and despair are understandable reactions to adversity. So too are the opportunities that people find. This is not to gloss over anyone’s misfortune or to suggest that they are solely responsible for addressing the situation they find themselves in. They are not. A person’s adaptive, problem-solving capacity is enhanced by a caring network and access to resources.

Adversity calls forth our ingenuity. We must do something because no one else is or will. Justice burns brightly. We try anything, borrow anything, cobble together anything at any hour of the day and night until something works or somebody does something. We act with a focus and creativity that we never thought we had. Adversity also cracks us open. We see the world as it is, not as we thought it was or want it to be. We embrace its complexities, contradictions, and ugliness, with a determination and love that we never thought possible.

The people profiled in this lesson treat adversity as an opportunity. While it may not be the opportunity they wanted, it’s the one they have been presented with. They have made use of their suffering and hardship to find common ground with others, often making improvements that have benefited many others.

My wish is that we find the natural strength that exists within each of us. That we find meaning in our struggles and losses. That we don’t treat them as personal failings and that we don’t shut ourselves off from others. As Sam Sullivan discovered, adversity may be the mother of invention, but love is another parent.

Mothering On CHRISTA COUTURE

Mothering On CHRISTA COUTURE

Resilience is born from suffering and reflected in celebration.

Singer, songwriter, storyteller, and self-described cyborg Christa Couture is no stranger to grief and loss. Her left leg was amputated when she was thirteen as a cure for bone cancer. Then her two baby boys, Emmett and Ford, died for different reasons, one at a day old, the other at fourteen months. In between, her father died. Later there was a divorce. Recently she had two surgeries on her neck—the first to remove a thyroid cancer, the second to address an arterial bleed that erupted shortly after and which threatened her singing voice and her destiny, a destiny that was foretold by the indigenous elder who, in honor of her mixed Cree heritage, gave her the traditional name of Sanibe, which means “singing woman.” “Grief is a very lonely feeling, and so getting to make songs about it and share those songs was a way that I could be less alone,” she told a radio interviewer. “It’s how I have survived the hardest parts of my life.”2

Despite her candor, Couture is careful about what she shares publicly. She simply knows there are parts of grief that naturally reveal themselves to others. So she makes those parts beautiful through her songs and blog posts. The rest remains private. Her philosophy might be summed up by the advice that a drag queen once gave her: “If you can’t hide it, decorate it.” A good example was her decision to post pictures of her recent pregnancy. Not seeing any pictures of pregnant women with disabilities online, she made her own. It was the first time she had taken off her state-of-the-art prosthesis for a photo. The leg, decorated in a floral fabric, leans against the wall as she sits cross-legged, looking directly at the camera. The pictures went viral. “I knew people might do a double take, because they’ve only been fed images of certain bodies,” she said. “But we need to normalize these differences.”3 She hopes that other disabled women will come across her images and feel that their difference is powerful. “Go get all glowy with your pregnant self,” she wrote. “Whatever body you’re in.”4

Although the surgeries changed her voice, Couture is still singing. And she is learning to celebrate. “I don’t just accept my disability—I can celebrate it.”5 She says she had become so focused on not letting her pain be swept under the rug in our get-over-it culture that she forgot to shine a light on her joys and many accomplishments—which include becoming the mother of a baby girl, hosting a radio show, and writing her new book, How to Lose Everything. It is scheduled to be published in late 2020. “It’s not that it gets easier, but it does change,” she says.6

Breathing Love into Zika THE GUERREIRA MOTHERS OF BRAZIL

Breathing Love into Zika THE GUERREIRA MOTHERS OF BRAZIL

Love and adversity are a powerful combination.

In the lead-up to Brazil’s 2016 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, the world’s gaze was fixated on what the media described as the horror and tragedy of congenital Zika syndrome (CZS). They portrayed Brazilian parents and their babies as grieving victims. They used the images as a backdrop to discuss the herculean challenge that Western science has to overcome to eradicate the virus. In doing so, the journalists missed another gaze—the look of love in these same parents as they fussed over their babies.

They also missed the determination of Brazilian parents, particularly moms, to rise to the occasion. These parents consider their children a blessing even though they face tough challenges and strains, including the demonization of their babies. They know that science and technology can’t solve every problem, and that they distract attention and deflect resources that should be available to support these families.

Brazilians with disabilities and their families receive limited government support. So a group of mothers who have had babies with CZS created United Mothers of Angels (UMA) to share information, referrals, and treatment, and to make sure their children are not forgotten. They call each other guerreiras (warriors). Germana Soares is their leader. “We are protesting so that this generation of special needs children will not be rendered invisible. Our babies are citizens, they have rights, and while they cannot speak we are their voice,” she said in an interview.7 Germana’s son Guilherme has already exceeded the predictions of doctors. He is starting to speak. “He has a really strong personality, he is very strong-willed,” said Soares. “He knows what he wants and when it’s a no, it’s a no.”8

Debora Diniz, a Brazilian anthropologist and lawyer, and author of Zika: From the Brazilian Backlands to Global Threat, described these mothers as “the domestic scientists who have been key in advancing our understanding of CZS” in an interview. She said they are guiding the “white coats and biomedical groups.”9

Radical Optimist HELEN KELLER

Radical Optimist HELEN KELLER

Adversity demands justice.

Mark Twain said that Helen Keller would be as famous a thousand years from now as when she lived. It wasn’t for the reasons most people think. What they know about Keller has been fashioned by the film The Miracle Worker and its two remakes. They know that a mysterious illness when she was a baby left her unable to see, hear, or speak, and that her teacher Annie Sullivan helped her learn how to read and write. Twain understood that there was more to Keller’s story. He was impressed by her intelligence, quick wit, and commitment to justice and equality.

Keller was a popular lecturer and writer who became known as the socialist Joan of Arc. “I, too, hear the voices that say ‘Come,’” she wrote, “and I will follow, no matter what the cost, no matter what the trials I am placed under. Jail, poverty, calumny—they matter not.”10 She campaigned for women’s and workers’ rights and an end to racial segregation. She was an early advocate of birth control. She was a cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). She wrote a series of essays on socialism called Out of the Dark. Keller believed that it was an unjust economic system that kept people with disabilities and others poor and unemployed. Her radical politics led to public criticism. Some newspapers criticized her by drawing attention to her disabilities, suggesting that her “mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development.”11 She even drew the attention of the FBI, which suspected she might be a communist because of her radical ideas. She wasn’t. Later in her life, she became a successful diplomat, representing the United States in post–World War II Japan.

Keller’s optimism wasn’t the cross your fingers and hope for the best kind. It was a learned optimism that emerged from the experience of adversity. She wrote in her journal, “Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, vision cleared, ambition inspired, and success achieved.”12 She advised people to hold their head high and look the world straight in the face. “For imagination creates distances and horizons that reach to the end of the world,” she wrote in The Story of My Life. She added, “It is as easy for the mind to think in stars as in cobble-stones.”13 Keller received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964.

Adversity Is an Opportunity AIMEE MULLINS

Adversity Is an Opportunity AIMEE MULLINS

The ability to adapt is a key survival skill.

If Aimee Mullins can change her legs, she thinks the least you can do is change your mind—about disability and adversity. She’s no stranger to either. Both her legs were amputated below the knee when she was a year old, due to a condition she was born with. She has twelve different pairs of prosthetic legs, changing them depending on the terrain, and whether she is running, going out for the evening, or simply wanting to change her height. Some she describes as wearable sculptures. She jokes that half of Hollywood has more prosthetic in their body than she does but we don’t think of them as disabled.

Mullins first attracted media attention for her athletic achievements when she set world records in the one hundred meters, two hundred meters, and long jump. Today she is better known as a fashion model—the face of L’Oréal—and as an actress, including playing Eleven’s mother on the Netflix series Stranger Things. She is also one of the reasons why Chris Anderson purchased and transformed TED Talks into a global phenomenon. Her three TED Talks have been viewed more than seven million times.

Mullins is regularly asked to speak about overcoming adversity, which makes her uneasy. She says adversity isn’t about triumph over tragedy, or about overcoming a challenge, unscathed. “It’s just change we haven’t adapted ourselves to yet,” she says in her TED Talk titled “The Opportunity of Adversity.”14 It changes us physically and emotionally. And our responsibility is not to shield our loved ones from adversity; it’s to prepare them to meet it with confidence and creativity.

Adversity is inevitable, she suggests. The question isn’t whether we will meet it but how. Seeing it as “natural, consistent, and useful” means that “we are less burdened by its presence.”15 She paraphrases Charles Darwin: “It’s not the strongest of the species that survives, nor is it the most intelligent that survives; it is the one that is most adaptable to change.”16

Better and Darker Angels ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Better and Darker Angels ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Making peace with darkness makes us wiser.

Abraham Lincoln is considered one of the greatest US presidents. The challenges he faced have been well documented. They included the death of his eleven-year-old son, Willie; an apparently loveless marriage; and the terrible death and discord of the Civil War. He also experienced clinical depression. In those days it was called “melancholy.” When Lincoln was in his twenties, neighbors occasionally took him in for fear that he might take his own life. His law partner observed that “his melancholy dripped from him as he walked.”17

According to Joshua Wolf Shenk, author of the book Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness, Lincoln’s depression “lent him clarity and conviction, creative skills in the face of adversity, and a faithful humility that helped him guide the nation through its greatest peril.”18 Lincoln’s open-heartedness and humanity derived from integrating the polarities of darkness and light in his own life. He didn’t separate Americans into two camps, North/South, victor/vanquished, or good/bad. He urged “an awe-inspiring sense of love for all” in his second inaugural address.19 In his first inaugural address, Lincoln said, “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”20

Image Maker FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT

Image Maker FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT

Adversity expands the heart.

The reason that the image of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) is on the American dime is because he founded the March of Dimes. In 1938, he encouraged people to donate by forming a march of dimes all the way to the White House to help find a cure for childhood polio. Dimes came by the truckload—2,680,000 dimes, or $268,000, in the first month. Jonas Salk benefited from the donations and eventually developed the polio vaccine. The American public had a general sense that Roosevelt had polio because he had retired temporarily from politics. Few understood that he was paralyzed below the waist and could not walk on his own when he returned. That’s because he stage-managed his appearances. On his first inauguration day, he rolled to the stage in his wheelchair, hidden by a barrier. Then he walked the last few steps, supported by one of his sons. He had hand controls in his cars so that he could be seen driving, and he banned people from taking pictures of him with his braces, wheelchair, or canes. Roosevelt felt the camouflage was essential because the designation “cripple” would have caused the erasure of a politician of that era.

Ironically FDR’s disability prepared him to lead the American people through the Depression, World War II, and the implementation of the New Deal. His secretary of labor, Frances Perkins, watched FDR’s long period of rehabilitation, which began in 1921 when he was thirty-nine. “The man emerged completely warm-hearted, with a new humility of spirit,” she said.21 His wife, Eleanor, said that polio had made her husband more sensitive to the pain of others and determined to do something about it. Roosevelt was much blunter. “Once you’ve spent two years trying to wiggle one toe, everything is in proportion,” he said.22

Roosevelt’s New Deal faced stiff opposition. It was criticized as either creeping fascism or closet communism, and as too much, too soon. Roosevelt persisted and was reelected in a landslide. One of the strategies his administration employed was nurturing the arts. The result was an outpouring of creativity that reflected the sentiments and values of New Deal policies. “I, too, have a dream,” wrote Roosevelt in a 1938 letter, “to show people in the out of the way places, some of whom are not only in small villages but in corners of New York City . . . some real paintings and prints and etchings and some real music.”23

Roosevelt’s success at political image making has meant that the allure of the New Deal lives on. Sadly, so does the effect of his personal image making, which hid his disability. The headline of an article written by Roosevelt’s grandson Curtis in 1998 reads, “FDR: A Giant Despite His Disability.”24 That is why advocates with disabilities ensured that the statue placed at the entrance to his memorial in Washington, DC, in 2001 shows him seated in a wheelchair. It was paid for with private money raised by the National Organization on Disability. Inscribed on the plaque is this quote from Eleanor Roosevelt: “Franklin’s illness . . . gave him strength and courage he had not had before. He had to think out the fundamentals of living and learn the greatest of all lessons—infinite patience and never-ending persistence.”25

Breaking Ground PEARL S. BUCK

Breaking Ground PEARL S. BUCK

Adversity gives birth to social movements.

Pearl S. Buck’s first book, The Good Earth, was published in 1931. It went on to become a classic of American literature. It won the Pulitzer Prize and helped Buck to become the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. The novel tells a story about the struggles of Chinese peasants during a period of drought before World War I. Wang Lung, the main character, has a child with a disability whom he loves and cares for throughout the starvation and hardships of peasant life.

In 1950, Buck broke new ground again when she wrote The Child Who Never Grew: A Memoir. The title reflects the diagnosis she received when her daughter Carol was born, a diagnosis she never accepted. During that era, parents who refused the advice of doctors to place their child in an institution and go home and forget about him or her were left in what Buck described as “private and sacred isolation.” Newspapers refused to let parents place ads seeking other parents who had children with disabilities. Buck explained that she started writing because she needed extra money. “For I knew all too well the cost of lifelong care for such a child. . . . I was well paid as teachers go, but now I had to earn much more.”26 The money she earned from The Good Earth paid for several years of her daughter’s schooling.

Pearl Buck’s decision to write about her daughter Carol helped give birth to the family arm of the disability movement. There is a direct connection between her and small groups of families who were banding together to advocate for their children throughout Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America. That included the Kennedy family. John F. Kennedy’s sister Rosemary had an intellectual disability. When he became president, he established what is now the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities. JFK’s sister Eunice Kennedy Shriver helped found the Special Olympics. Collectively, this international movement of families persuaded the UN to create a Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons in 1975. It was the first UN Declaration of any kind. Buck said that placing her daughter in a school affected her for the rest of her life: “I don’t know of any blow in all my life that was as rending. It was as if my very flesh were torn.”27

The Dark Side of the Game TIM GREEN

The Dark Side of the Game TIM GREEN

Some things in life are costly. Others are priceless.

Tim Green made his reputation tackling opposing quarterbacks for the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons. He then became a successful broadcaster and writer. In 2016, he was diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, named after the New York Yankees baseball star, who also had ALS. Green believes his ALS is the result of the constant blows to his head that he received as a defensive lineman for the Atlanta Falcons. He lost track of the number of concussions he suffered. “I used my head on every play. Every play. Every snap. It was like throwing myself headfirst into a concrete wall,” he said in an interview.28 He said that he might not have developed ALS if the current regulations that limit helmet-to-helmet contact in practice and penalize it in games had been in place. He believes football has taken ten to twenty years off his life.

Green made his diagnosis public on CBS’s 60 Minutes when he could no longer hide his symptoms. Denying pain and injury was a survival strategy that worked for him when he was playing football. “I’m a strange guy,” he told an NPR interviewer. “I get something in my head and I can just run with it. I was really afraid I had ALS. But there was enough doubt that I said, ‘All right, I don’t. Let’s not talk about it. Let’s not do anything.’”29 Green was ambivalent about whether playing football was worth it. “Can I say getting ALS was worth it? I don’t know. I don’t know.”30 He pointed out that most people who play football don’t get ALS.

Green is determined to maintain the positive attitude that he has had all his life. “So whenever the end point is,” he said, “I ask to be strong enough to maintain that positive attitude no matter what the challenges are.”31 After leaving football, Green became a best-selling author. He is writing his thirty-ninth book with a sensor on his glasses that he uses to point at letters on the computer. He said he wants to continue being the best dad, lawyer, writer, and businessperson he can be. “I don’t know anyone more fortunate and blessed than me—even with this,” he told 60 Minutes.32 Green’s memoir is called The Dark Side of the Game: My Life in the NFL.

Note: Tim Green is one of a growing number of football players who have been diagnosed with ALS. The NFL’s current concussion settlement acknowledges the link between countless head collisions and ALS. It includes payouts for former players who have ALS, including Green.

Did You Know . . . the First Bicycle Was a Wheelchair

In 1655, Stephan Farffler, a Nuremberg, Germany, watchmaker, invented a three-wheeled device called a manumotive carriage. It is believed that Farffler either had a spinal cord injury or had had his legs amputated. He moved the carriage by turning a hand crank attached to the front wheels. It was the first self-propelled wheelchair and the forerunner of the tricycle and bicycle.

Did You Know . . . Hand Signals in Baseball

Hand signals in baseball were devised by William Hoy in the late 1800s. Hoy was a center fielder who holds the record for throwing three runners out at the plate in a single game and hitting the first-ever grand slam home run in the American League. He was also deaf. He had to ask his coaches whether a ball or a strike was called. While awaiting their answer, the pitcher often sneaked in a quick pitch, striking the batter out before he was ready to swing. Hoy devised hand signals that the third base coach could use to relay the umpire’s call so that he could keep his focus on the pitcher.

Nowadays, more than one thousand silent instructions are given during a regular nine-inning baseball game.