Chapter 3

Should You Change Horses?

All growth is a leap in the dark, a spontaneous, unpremeditated act

without benefit of experience.

—Henry Miller 1

You have been carjacked.

You are now sitting in the passenger seat and a man in a ski mask is pointing a gun at you while he drives your car. You have only a split second to size up the situation. Does he intend to kill you, or will he drop you off somewhere up ahead on the road? Your door is unlocked, so the thought passes through your mind that you could jump out of the moving car onto the street and run away. But would you survive the jump? Are you better off staying in the car with the danger that you know, rather than making a leap into the unknown?

How do you know it is the right time to give up the world that you know, even when it has become dangerous, for something new?

In your personal and business life, you will often face such forks in the road. They will not always be this dramatic, but the choices can be just as sharp and the implications just as ambiguous. You will be faced with the choice of holding onto an old model that may not be working or adopting a new one with uncertain repercussions. If you are facing trouble in your marriage or at work, do you abandon your model of family life or your model for a career, or do you stick with the old model despite the problems? When do you need to make the leap, and how do you do it? This chapter examines these issues, beginning with the unfortunate story of Lord George Simpson, who perhaps should have looked a bit harder before he leaped.

Imagine you are Lord George Simpson, who took the reins of General Electric Company (GEC) in the United Kingdom (no relation to U.S.-based General Electric) in September 1996. Under the leadership of your predecessor, Lord Arnold Wein-stock, GEC had risen to become one of the most powerful companies in Britain. It was an extremely successful money-making machine that dominated British defense, power and electronics.

Weinstock, who ran the company with an iron fist for 33 years, introduced an approach to operating the conglomerate in the 1960s that was radical for its time in the UK. He sat in his office and ran the corporation's 180-some companies based on a set of key financial ratios, firing managers when their ratios dipped below acceptable levels. He rarely walked into his own factories, but he watched the numbers like a hawk. And his managers trembled when they heard him on the other end of the phone line. He stripped away wasteful overhead and instituted strong controls. He added new businesses through major acquisitions.

While Weinstock indulged a personal passion for gambling on horses at the racetrack, he didn't leave anything at the company to chance. He created a model for running the business that was so successful, it became the standard for other large British firms.

While Weinstock's mechanical model and conservative strategy for the business were rewarded by strong financial performance, at least according to his measures, the low-growth approach was punished by the market in boom times. As Weinstock neared the end of his term in the mid-1990s, GEC's share price was languishing. Investors, who wanted growth, were rewarding GEC's rivals who entered microchips or consumer electronics. Weinstock and his managers were flogging performance out of existing businesses, but they were not aggressively pursuing the technology-driven growth that other competitors were achieving in computing and telecommunications.

As George Simpson, when you enter the building on your first day, you have inherited a very successful company, but one that is no longer the darling of investors. You are sitting on a pile of more than ![]() 2 billion in cash. As you walk into the stodgy offices in Hyde Park Corner and settle down into Weinstock's large chair under an oil painting of one of the racing horses he so much admired, you begin to consider your strategy. GEC is a solid war-horse, but it certainly can't keep pace with the nimble thorough-breds running past it to the high-tech winner's circle. Is Weinstock's powerful organization finally losing its footing? The cozy political relationships that allowed for lucrative cost-plus defense contracts are fading fast. New technologies are transforming the competitive landscape and creating red-hot opportunities. Clearly, it seems, a different model is needed. Isn't it time to switch horses? Do you stay the course or put your own mark on the organization? What would you do?

2 billion in cash. As you walk into the stodgy offices in Hyde Park Corner and settle down into Weinstock's large chair under an oil painting of one of the racing horses he so much admired, you begin to consider your strategy. GEC is a solid war-horse, but it certainly can't keep pace with the nimble thorough-breds running past it to the high-tech winner's circle. Is Weinstock's powerful organization finally losing its footing? The cozy political relationships that allowed for lucrative cost-plus defense contracts are fading fast. New technologies are transforming the competitive landscape and creating red-hot opportunities. Clearly, it seems, a different model is needed. Isn't it time to switch horses? Do you stay the course or put your own mark on the organization? What would you do?

Your choices at such forks in the road are often the most important decisions you can make. How do you know whether the old business model, and the mental model on which it is based, are worn out or just need to be reshod? How do you know that the new model will live up to its hype?

All the time that people are making such decisions about which models to bet on, the horses keep on running; there isn't a pause in the action. Not having much time to assess the situation, people tend to keep rolling over the same old bets, or to jump impulsively from horse to horse.

Place Your Bets

There are no easy answers to the underlying questions. In making decisions about changing mental models—whether they involve a corporate growth strategy through acquisitions or a personal "antigrowth" strategy of diet and weight control—you face the danger of two kinds of serious mistakes:

- Being left behind. The first mistake is to stick with the wrong model and be left behind. You are backing an old nag that should have been put out to pasture long ago. You are running your business on an industrial model in an information age. You are eating a processed-food diet of the 1950s while knowledge of nutrition and exercise have moved forward. The rest of the pack, with better mental models, thunder by, and you are left in the dust. You fail to seek out something new until your losses accumulate or the horse you are backing keels over. Sometimes then it is too late. As Simpson took over GEC, he must have worried that the model that Weinstock had used to build the company was losing steam. It seemed that the time was ripe for a revolution, while the company still had the resources to pull it off. When you leave the safety of tried-and-true bets, however, you risk a second possible mistake.

- Backing the wrong horse. In jumping to a new mental model, you might abandon a perfectly adequate one before it has been exhausted. An even more serious danger is that you might change to a model that turns out to be much worse. When Internet start-ups and venture capitalists convinced the world to look at eyeballs rather than ROI, they attracted big bets on a model that focused on how many users were looking at their Web pages rather than how many dollars were flowing into their coffers. A short time and billions of dollars later, many investors gave their heads a vigorous shake and were a bit shocked to see this same picture through very different eyes. They concluded that their bets, in many cases, had been unwisely made, based upon a vague and poorly understood model. As a consequence, there were big losses. This is the trouble Lord Simpson ultimately found himself in.

A Wild Ride

Lord Simpson apparently decided it was time for a revolution. Weinstock had described his successor as "a man of vision," and he was right. Simpson moved the company out of its conservative Hyde Park headquarters to trendy offices on Bond Street and changed its generic name to the more nuanced Marconi, signaling his intent to concentrate on the hot-growth sector of telecommunications. The company sloughed off the old defense business to British Aerospace and drove full bore into telecom.

Marconi now had the kind of focus on growth that shareholders dream about. Lord Simpson had transformed the boring, old-fashioned conglomerate into a dynamic, sharply focused high-tech firm. As the bright red 1999 annual report gushed: "Our future ... will be digital. We will lead the race to capture, manage and communicate information. We will ride the rising tide of demand for data transmission. We will be a leading global player in communications and IT."2

The dream was seductive. Despite signs that the telecom market was weakening, Simpson held to his view of the world. He had burned his boats to make a stand on this foreign shore and there was no way back. As competitors such as Nortel, Nokia and Ericsson warned of declining sales and profits in the first quarter of 2001, Simpson stubbornly clung to his view of telecom as a hot market. On May 16, 2001, he told shareholders: "We anticipate the market will recover around the end of this calendar year, initially led by European established operators ... we believe we can achieve growth for the full year, as a result of our relative strength supplying these operators."3

As commentator Frank Kane wrote in the Observer in August, while the rest of the world saw that Marconi's vision was collapsing, Simpson refused to give up on his view. He was, perhaps, too deeply committed. Kane wrote that "What might have been called brave determination a month ago has turned into willful stubbornness coupled with a blind refusal to see reality."4

The dream of Marconi turned to a nightmare as the company was swallowed up in the telecom bust, which left the global industry with a hangover of ![]() 750 billion in excess capital expenditure and debt. By September, Simpson and his top managers had stepped down from a business that was reeling. Marconi shed 10,000 employees. The more than

750 billion in excess capital expenditure and debt. By September, Simpson and his top managers had stepped down from a business that was reeling. Marconi shed 10,000 employees. The more than ![]() 2 billion in reserves existing when Simpson took charge were gone, replaced by a crater of more than

2 billion in reserves existing when Simpson took charge were gone, replaced by a crater of more than ![]() 4 billion in debt. The company's share price plummeted from a vigorous peak of

4 billion in debt. The company's share price plummeted from a vigorous peak of ![]() 12.50 to the comatose level of four pence at the time of Lord Weinstock's death in July 2002.5 He lived to see the once-great company he had built brought to the brink of bankruptcy. It was, in the words of the BBC, "one of the most catastrophic declines in UK corporate history."

12.50 to the comatose level of four pence at the time of Lord Weinstock's death in July 2002.5 He lived to see the once-great company he had built brought to the brink of bankruptcy. It was, in the words of the BBC, "one of the most catastrophic declines in UK corporate history."

How did this "man of vision" go so wrong? Marconi's business was built on a chain of assumptions. In 2000, when telecom operators were spending more than 25 percent of their revenue on expanding their networks, they had a voracious appetite for Marconi's telecom equipment and software. This spending was, in turn, based on projections of a rapid increase in customers and an insatiable demand for bandwidth. These projections were wildly optimistic and, as they collapsed in 2001, the industry suffered from overcapacity and quickly cut back on spending. During its acquisition spree, Marconi had paid top dollar to create end-toend solutions for customers, based on a perception of continued growth in the sector. When these projections of growth collapsed, so did Marconi's business. All these changes occurred in the broader context of several decades of deregulation that had transformed the telecom industry.

The business models Lord Weinstock and Lord Simpson created were based upon totally different mental models. Lord Weinstock ran a business that was risk averse and very conservative, a vision that may have been shaped by his childhood as a poor Jewish immigrant from eastern Europe. He ran the business by the numbers. The affable Lord Simpson, a member of seven golf clubs, worked from personal relationships. He had built his career upon making deals. He had sold Rover to BMW and closed other major deals earlier in his career that helped in selling GEC's defense business and making a series of acquisitions to build Marconi's capabilities.

Both men had become successful based on their world views, and both in different ways were blinded by them. Lord Weinstock's reliance on financial controls over personal management may have led to his poor judgment in appointing Simpson as his successor. Lord Simpson's reliance on personal relationships and deal making may have blinded him to the importance of rigorous controls that are needed to run the business. As both men entered a process of establishing a new model for GEC's business, they made the dangerous move from their areas of deepest experience into new industries and ways of operating that were not familiar.

To institute a new order of things, leaders need to be able to persevere against the naysayers and rise above obstacles. They need to be able to overlook the limits of today to build the business for tomorrow. When does the "brave determination" that is needed to champion a new vision become "a blind refusal to see reality"?

There are several psychological forces that tend to keep people committed to a course of action long beyond the point when they should rationally quit. The first is the "sunk cost fallacy." This can be seen in the actions of the stock market investor who has watched share prices of a company plummet from ![]() 60 to

60 to ![]() 20. At this point, instead of objectively assessing the potential of the stock, the investor may hold onto this stock—or buy more shares—in hopes of regaining these "sunk costs."6 But if the company is collapsing, there will just be more losses. Managers with deep investments in a given project, financial or reputational, will likely sustain it beyond when they should objectively pull the plug. This tendency to deepen commitment can also be seen in political commitments such as the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, where past investments made it very difficult to pull out.7

20. At this point, instead of objectively assessing the potential of the stock, the investor may hold onto this stock—or buy more shares—in hopes of regaining these "sunk costs."6 But if the company is collapsing, there will just be more losses. Managers with deep investments in a given project, financial or reputational, will likely sustain it beyond when they should objectively pull the plug. This tendency to deepen commitment can also be seen in political commitments such as the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, where past investments made it very difficult to pull out.7

A related factor that clouds our judgment about when to quit is the escalation of conflict. In a competitive situation, investments in a given course of action can reach ludicrous levels. For example, in an auction game in which two competitors bid to win a dollar bill (with the winner paying the sum of the two final bids), bidding quite often ends with the winner paying three to five dollars to obtain a single dollar.8 There are a variety of factors that drive this escalation. Initially, it might be a desire to make money or prevent a future loss, but as the bids mount, regaining losses or simply outdoing an opponent become more important.9 In the dollar auction, the ridiculousness of such bidding is very clear, but the same effect can lead to overbidding for much higher stakes (such as the G3 wireless auctions in Europe) and a heavier "winner's curse." Once Simpson was committed to his course of action in transforming GEC, it became very difficult to pull back, despite the mounting losses.

This is not to say that GEC should have continued on the course set by Lord Weinstock. His model of centralized financial control of a conglomerate may have been too slow for the late 1990s. It was due for a change, perhaps, especially since the market did not value such companies highly. There are other cautionary tales from companies that changed too slowly—Xerox seeing its business undermined by Japanese competitors in the 1980s or, a decade later, IBM watching its business drained away by the PC and Sears seeing its department store whittled away by the rise of new retail formats. IBM was so focused on tracking measures for mainframes that it missed the fact that its total share of computing was declining. Sears was watching department store rivals so intently that it missed the rise of different niche retail formats that were taking business away in clothing or hardware. When the racing bell goes off, it is dangerous to stand still.

Simpson's tale of woe emphasizes the inherent difficulty of shifting mental models. If telecoms had fulfilled their outrageously rosy predictions, Lord Simpson would have been a visionary and a hero who had taken his company in a bold new direction. Instead, he walked away from the track in disgrace, having squandered virtually his entire inheritance. Other choices, however, had been open to him, other than betting the entire company on a new direction.

Knowing When To Switch Horses

To their credit, Lord Simpson and Lord Weinstock did recognize that the world was changing and that GEC needed to change. This recognition is the first challenge, because it is often difficult to see there even is a problem with the old model until it is too late. While businesses can be destroyed by the race to new models, others are also destroyed by standing still. How do you recognize when you need to change your mental models?

- When the old model dies, you have no choice. The clearest sign that you need to shoot your old model is when the old nag stumbles and breaks a leg. When you face a serious crisis or failure of the old model, there is no question that you need to find a new one. If you have to shoot the current horse, you may find yourself on the side of the road with no transportation. When your old models in various areas fail, you risk losing your health, eroding the profits in a business or undermining the prosperity of society. You face dangers in waiting this long to act. How do you see the trouble coming before you encounter a full-blown crisis?

- Pay attention to outliers and "just-noticeable differences." In psychology there is a concept of a "just-noticeable difference." It is a change that could be noticed but is absorbed by the process of normalizing variance. When you see something that doesn't fit the current model, you make it fit. In the movie The Matrix, in which the characters are living in a simulated world that they believe is real, it is only through small glitches in the program that they are able to see beyond this illusion. Most of the time, people normalize the variations that they see, and this can get them into trouble. The temperature rises slowly in a room, and you don't realize the change until you break into a sweat. You dismiss chest pains or lack of energy until these symptoms turn out to be a serious medical problem. A company like Motorola is building analog wireless phones at a time when the industry is turning to a global digital standard, but because its current business is successful, it fails to recognize quickly enough that the world is changing. As a result, it is forced to concede significant market share to Nokia, Ericsson and others.

Often these small variations are truly insignificant, but they can sometimes turn out to be the tail that wags the dog. If you systematically pay attention to them, you can recognize when they should make you reconsider your mental models. The more hubris you have built up as an individual, an organization or a society, the more you need to be alert for these outliers and to look at them from different angles to see what they mean. As an adult with many years of experience, you may need to deliberately take time to sit down with young people, read widely or otherwise seek out views that contrast sharply with your own. As a mature organization, you may need to create processes for reporting the information around the fringes rather than just looking at the big averages or the statistics that you have always tracked. These past statistics will tell you where you have been but not where you are headed. You need to look for differences that indicate your old model is not working or that the potential for a new model has emerged.

- Avoid cognitive lock. Part of the challenge of seeing these small variations is "cognitive lock." People become so fixed in a single view of the world that they filter out all information that conflicts with this model and are unable to see another possible explanation. The problems with the O-rings on the Challenger space shuttle were apparent before the disastrous explosion, but they were attributed to quality control in the manufacturing process rather than to the effect of low temperatures. Viewing the challenge through the lens of disciplinary training in manufacturing or engineering let the real problem remain unseen. If your education is in marketing, you'll tend to see problems as marketing problems. If your education is in finance, you'll see everything in terms of ROI and cash flow.

- Create an early warning system. One way to recognize small differences and avoid cognitive lock is to create systems for identifying specific changes in your environment. During the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union had their fingers on the buttons of nuclear weapons aimed at one another, they developed sophisticated early warning systems to let them know when trouble was headed their way. These systems essentially were designed to signal that the deterrent model of "mutually assured destruction" (MAD)—a standoff where neither side moves because of the threat of annihilation from the other—had broken down. In this case a new model, of open nuclear war, would have been signaled, requiring a different set of actions.

You need to develop early warning systems so you know when to look more closely at your models. Robert Mittelstaedt, Jr., has pointed out that many serious disasters from airline crashes or nuclear accidents occur through a chain of multiple mistakes. 10 There is often time to recognize and address the initial mistakes, but they are overlooked until they become compounded. Chemical companies and other firms have found it very effective to conduct analyses of "near misses," instead of waiting for major catastrophes. The major accidents usually do lead to a thorough analysis, but the near misses often are overlooked. Managers wipe their brows and go back to work. By systematically identifying and making sense of these near misses, companies can achieve higher levels of learning and correct potential problems without the pain of very serious mistakes.

Early warning systems should be based on real-time feedback and have trip wires for action or more intense investigation. Any latencies or lags in basic control systems cause instability. The trip wires should be based on your understanding of your current models. If you know your models' limits, and the assumptions upon which your models are based, you can monitor when the limits have been crossed and the assumptions contradicted. A missile crossing into U.S. territory would have been a clear sign that the assumptions of the Cold War standoff were no longer valid.

These trip wires are not the kind of absolute cutoffs for ratios that Lord Weinstock monitored, but rather events that call for increased scrutiny in a certain area. For example, a credit card company set trip wires for a certain level of customer complaints, employee or customer attrition, reductions in average purchases or declining frequency of use of the card. Companies also set up trip wires for detecting fraud. If a customer uses a card outside his or her normal pattern or geography, the company will turn down the charge until the customer verifies it.

The problem with trip wires and warning systems is that they can sometimes blind you to larger changes in the environment. Trip wires are based on preconceived scenarios of possible events on the current model. Other events, which you may not anticipate at all, could sneak up on you from a different direction. The "digital dashboards" that are being developed to keep critical performance measures in front of managers in organizations tend to focus attention on a few key metrics. The U.S. and Soviet systems were designed to recognize a nuclear missile attack but would have been ineffective against a suitcase bomb or other terrorist act. Lord Weinstock's ratios were not what allowed him to recognize the changing terrain of investment and the telecom industry.

The more you rely on systems to guide your actions, the more you may erode the intuition to see something new. In addition to these more rigid systems for running the business, you also need to cultivate flexible metrics and monitoring. You need the tactile experience of your "hands on the wheel." The best race car drivers are not necessarily those with the best dashboards but rather those with the best feel for the road. You need to look up from the dashboard occasionally and peer out the front and side windows to ensure you are truly headed in the right direction.

- Look at the world through the eyes of customers. One way to get a fresh view of your products or services is to look through the eyes of your customers. Too many companies are internally focused, so customers can offer a fresh perspective on the business.

- Recognize fads. When people decide to abandon their old mental models, they become much more susceptible to the crosswinds of fads, pursuing mirages that appear just beyond the horizon. The assumptions can be wildly off, as was Simpson's view of the growth of telecom. Similarly, in personal life, when you set out to change your traditional diet, you can be swept into an endless series of fad diets, some with radically different mental models. Some are based on taking pills or fortified drinks to replace meals; some strip away almost all red meat and encourage high-fiber, low-calorie eating; while others, such as the Atkins diet, allow unlimited meats and cheeses while scorning carbohydrates. Barry Sears' 40/30/30 ZONE diet calls for a balance of 40 percent carbohydrate, 30 percent protein and 30 percent fat. Some diets are based on eating all you can of certain foods on certain days—or an unlimited quantity of a certain food such as cabbage soup—while others are designed around periods of fasting where you eat no foods. Some are based on one-size-fits-all approaches, while others, such as the plan proposed by Peter D'Adamo in Eat Right for Your Type, tailors the diet to your specific blood type—recommending a hunter-caveman diet for Type Os while Type As are to eat a more vegetarian diet. Can all these diets be right?

In assessing potential new models, you need to be rigorous in your analysis. What is the basis for the claims? Can the model really deliver on its promise? In what ways does this new mental model create a different set of blind spots and how can you protect yourself against these?

- Know yourself. Depending on your own experience, you can face different kinds of pitfalls in shifting models. Very inexperienced people, in general, will tend to jump too quickly to embrace a new model. Most experienced people, in general, have a tendency to stick too long with the old model. By understanding ourselves, we can better avoid being blinded by either maturity or inexperience.

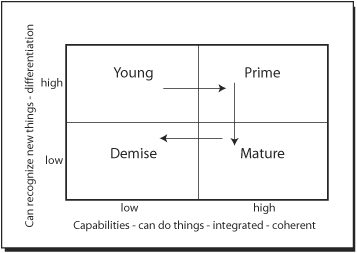

As illustrated in Figure 3.1, young people or start-up organizations have high differentiation (are able to see the world through fresh eyes) but have fewer capabilities for action.11 As they age, they reach a prime state where they are both able to recognize new things and have the capabilities needed to act on these insights. Maturation follows, when they are still good at getting things done but increasingly are locked into their well-worn models and cannot recognize new things. They have accumulated considerable experience, which they tend to use to explain everything, whether the explanation actually fits or not. As differentiation and capabilities sink low, the individual or organization enters demise.

Flexibility and openness to new ideas, which are more common in young individuals and in start-ups that are still formulating their processes and mindsets, can lead to a tendency to run from fad to fad, chasing new models merely because they are new. On

FIGURE 3.1 Knowing yourself

the other hand, the status quo approach, which is more common in mature individuals and organizations, leads to a tendency to dismiss new opportunities and mindsets. This is the approach seen in Lord Weinstock, who stuck doggedly to his old models even as the world was changing around him. The danger if yours is a mature organization is that you will back the wrong horse, missing changes in your environment because all new information will be force-fitted into the old model. With maturity, you have considerable experience and a vast mental model repertoire, which have served you well but are both a blessing and a curse. Demise follows when the ability to get things done diminishes and new things are increasingly difficult to handle.

Individuals have little choice but to follow this path from youth to demise in their physical development, although many consistently reinvent themselves to stay young in their thinking. Organizations generally react to a perception that they are headed into decline by attempting to reinvent themselves and bring in new leadership, as GEC did with the arrival of Lord Simpson. This is a turning point for the organization, and a potentially dangerous one. It is like a heart transplant. In attempting the transition from the old to the new the patient may gain many more productive years of life—or may be lost on the operating table.

Some visitors to the racetrack will have a tendency to stick to the same horses and riders they have always known. Others will tend to jump from horse to horse, backing whatever hot new jockey or horse enters the starting gate. Both tendencies will lead to certain kinds of mistakes. Knowing how you approach the process of shifting new mental models can help you be more vigilant about errors.

- Beware of the midlife crisis from postponing change. Because of this cycle, mature individuals and organizations sometimes hit a "midlife crisis." They avoid changes for a long while and then make a dramatic leap, often with very negative consequences. The impact of the corporate version of this process can be seen in Lord Simpson's decisions. This pattern can also be seen in the wholehearted embrace of the Internet in the late 1990s by companies that had long dismissed it. In the more personal version of this crisis, the protagonist may give up the minivan for a sports car, abandon a marriage of many years to revisit the bars and dating of his youth or give up a stable career to launch a new business venture. Some people use this route to successfully reinvent their lives, but many destroy their family relationships and their careers in the process, with little to show for it at the end. They become frustrated with their old mental model and essentially throw it out to adopt a new one.

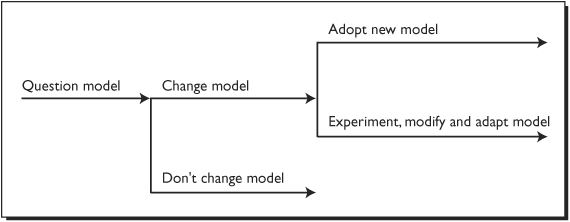

- Use experimentation to avoid a leap in the dark. One way to avoid the "midlife crisis" and minimize the need for dramatic leaps is to engage in continuous adaptive experimentation. (We'll discuss approaches in Chapter 7.) Though Henry Miller contends that leaps in the dark are necessary for growth, they are not always necessary and they don't have to be in the dark. People often present options in the form of stark, binary positions (staying or leaping, resting on GEC's laurels or reinventing its future), but usually there are many more options. The fork in the road presented by a new mental model is more complex, as illustrated by Figure 3.2. At these decision points, you could decide to keep your existing model without changing it; throw out the old model and adopt a new one, as Lord Simpson appeared to do; or conduct experiments, monitor and modify or adapt your model as needed. Unless an extreme shift is needed, this third approach is very attractive. With more experimentation, Lord Simpson might have discovered the weaknesses of his model at a lower cost. You do need to beware of using "experimentation" as an excuse to avoid courageous changes that are needed. In many cases, however, as Shakespeare put it, "discretion is the better part of valor." Why take a big and dangerous leap when you can design experiments that offer you insights with a lot less danger?

In reality, there are even more degrees of freedom than are suggested by Figure 3.2. You may not need to choose rigidly between the old model and the new. Instead you can develop a portfolio of models and apply the one that works best for the specific situation. Simpson didn't have to abandon Weinstock's old ratios and controls. They embodied quite a bit of wisdom that might have served the new organization well, even as it created new models and moved into new directions. In this way, paradigm shifts are not absolute and irrevocable, but rather "a two-way street," as discussed in Chapter 4.

FIGURE 3.2 Choices for change

Off To The Races

The horses are already out of the starting gate. Your life and your business continue to race forward. You have placed your bet on a given model, and it has probably served you well up until now. Is it time to change horses? How do you avoid making the mistakes that GEC made in shifting its business and mental models? How do you know when to switch horses? How do you avoid backing the wrong horse or making a series of bad leaps?

Even under the best of circumstances, not all your bets will pay off. The story of Lord Simpson's decisions in this chapter, with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, is not intended as a personal critique. Everyone has made similar—although perhaps less dramatic—mistakes. The important question is: What can you learn going forward?

Given that mental models determine your reality, it is your understanding of your mental models—and knowing when to change them—that determines your opportunities for success and your risks of failure. The chapters that follow discuss this process of building bridges between old and new mindsets, engaging in adaptive experimentation and managing the challenge of complexity. Through these and other approaches, we can recognize the need to change and move in directions that are neither a leap nor in the dark.

Endnotes

1. Miller, Henry. The Wisdom of the Heart, ©1960 by Henry Miller. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

2. GEC Annual Report and Accounts. 1999.

3. Randall, Jeff. "Where Did Marconi Go Wrong?" BBC News. 5 July 2001. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/1423642.stm.

4. Kane, Frank. "Steer Clear Until Simpson Goes." The Observer. 19 August 2001. http://www.guardian.co.uk/Archive/Article/0,4273,4241635,00.html.

5. "Obituary: Lord Weinstock." The Economist. 27 July 2002. p. 85. Heller, Robert. "A Legacy Turned into Tragedy." The Observer. 19 August 2002. http://observer.guardian.co.uk/business/story/0,6903,776226,00.html.

6. Staw, Barry M. "The Escalation of Commitment to a Course of Action," Academy of Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 1 (October 1981), pp. 577–587.

7. Staw, Barry M., and Jerry Ross. "Commitment to a Policy Decision: A Multi-Theoretical Perspective," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1 (March 1987), pp. 40–64.

8. Shubik, Martin. "The Dollar Auction Game: A Paradox in Noncooperative Behavior and Escalation," Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 15, No. 1 (March 1971), pp. 109–111.

9. Teger, Allan T. Too Much Invested To Quit, New York: Pergamon Press, 1980, pp. 55–60.

10. "Want to Avoid a Firestone-like Fiasco? Try the M3 Concept." Knowledge@Wharton. 28 September 2000. <http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/articles.cfm?catid=2&articleid=242>.

11. This is based on an interpretation of the work of Nobel-prizewinning biologist Gerald Edelman.