Preface

Hijackingo Our Minds

At first glance, mental models may seem abstract and inconsequential. But they cannot be dismissed as optical illusions, parlor games or academic curiosities—all in our head. Our models affect the quality and direction of our lives. They have profit-and-loss and even life-and-death implications.

The debate about U.S. intelligence following the September 11 terrorist attacks illustrates the difficulty of making sense in today's complex environment. Congressional post-mortems focused on who knew what when—on the information—but not on the more critical mental models that shaped how that information was processed. As is almost always the case in our information age, what led to the tragedy was not primarily a shortage of data. Plenty of data points indicated that an attack using an aircraft as a missile was possible, and there was even information pointing to potential members of the conspiracy. While more specific information could have been gathered and shared among different agencies, the failure was only partially one of data gathering. This was not a failure of intelligence per se. It was, at least in part, much more a failure to make sense.

Information was filtered through existing mental models related to terrorism and hijackings. For example, middle-class, clean-cut young working men with everything to live for did not fit the profile of the stereotypical wild-eyed young fanatics who became suicide bombers. So when these apparently more stable men began studying in flight school or asking about crop dusters, the possibility of terrorism was filtered out. Hijackings also followed a certain well-established pattern. The plane and its crew typically were taken hostage and flown to some remote location, where the hijackers made demands. Pilots were instructed that the best course of action for passengers and crew was not to resist. During the September 11 attacks, the information was filtered through a set of mental models that made it hard to see what was really happening until it was too late.

The events of September 11 also dramatically illustrate the power of shifting mental models. When passengers on the fourth plane, United Flight 93, received reports by cell phone from friends and family about the attack on the World Trade Center, several quickly realized that this was not a typical hijacking. They could see that their own aircraft would be used as a missile against another target. In a matter of minutes, they were able to transform their mental models and take heroic actions to stop the hijackers. As a result, the last plane failed to reach its target, crashing in a field in western Pennsylvania, a tragedy that could have been much worse if some of its passengers hadn't been able to make sense of what was going on and move to stop it. The passengers and crew of Flight 93 were presented with a picture that was similar to the hijackings earlier that day. What they suddenly developed, however, was a different mental model. They were able to quickly make sense of what was happening and to act on this new understanding. And that made all the difference.

Mental Models

One of our most enduring—and perhaps limiting—illusions is our belief that the world we see is the real world. We rarely question

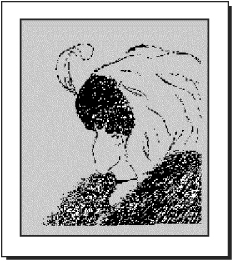

Romancing the Internet: The picture didn't change dramatically, but first we saw an attractive young woman, then an old crone. W. E. Hill, "My Wife and My Mother-in-Law."

our own models of the world until we are forced to. One day, the Internet was infinitely attractive. It could do no wrong. It was magnificent and beautiful. The next day, it was overhyped and ugly. It could do nothing right. Nothing had changed about the picture, yet in one instant we saw it as a seductive young woman and the next minute we rejected it. What happened?

This is called a "gestalt flip." The lines and data points are the same, but the picture is dramatically different. What has changed? Not the picture, but our making sense. What is in front of our eyes is the same. What is behind our eyes has changed. The same sight produces a very different perception.

We use the phrase "mental models" (or "mindsets") to describe the brain processes we use to make sense of our world. In recent decades, science and technology have progressed to the point where we can undertake direct observation of the brain. This is starting to transform philosophy and neuroscience. Instead of just thinking about thinking, we can now directly monitor brain processes as we think and observe. This research is generating a vast amount of experimental data. Confronting the incredible complexity of the brain, a range of neuroscience theories have emerged to explain what is going on inside our heads. In business and other organizations, these interactions become even more complex, as individuals with their own mental models interact through group decision making or negotiation, and they are susceptible to biases such as "group think" that can limit flexibility and constrict options.

As we were leading transformation initiatives at the Wharton School and Citicorp, and helping other executives transform their organizations, we began to realize how important these mental models are to the process of change. We have written this book to explore the implications of mental models for transforming our businesses, personal lives and society. This book does not support a specific interpretation of the neuroscience evidence, but it does recognize that the brain has a complex internal structure that is determined genetically and shaped by experience.

The ways we make sense of our world are determined to a large extent by our internal mind and to a lesser extent by the external world. It is this internal world of neurons, synapses, neurochemicals and electrical activity, with its incredibly complex structure—functioning in ways we have only a vague sense of—that we call the "mental model." This model inside our individual brains is our representation of our world and ourselves. (The appendix provides a more detailed explanation of developments in neuro-science that have influenced the thinking behind this book.)

Mental models are broader than technological innovations or business models. Mental models represent the way we look at the world. These models, or mindsets, can sometimes be reflected in technology or business innovations, but not every minor innovation represents a truly new mental model. For example, the shift to diet soft drinks was a tremendous innovation in the marketplace, but it represents only a minor change in mental models. Our mental models are much deeper, often so deep that they are invisible.

As a core component of our perception and thinking, mental models come up often in discussions of decision making, organizational learning and creative thinking. In particular, Ian Mitroff has explored their impact in creative business thinking in several books, including The Unbounded Mind with Harold Linstone.1These authors examine the need to challenge key assumptions, particularly in moving from "old thinking" to new "unbounded systems thinking." Peter Senge discusses how mental models limit or contribute to organizational learning in The Fifth Discipline and other works, and John Seely Brown examines the need to "unlearn" as the world changes.2 J. Edward Russo and Paul J.H. Schoemaker emphasize the role of framing and overconfidence in decision making in Decision Traps and, more recently, in Winning Decisions.3 Russell Ackoff, in Creating the Corporate Future4 and other works, stresses the importance of approaching planning by challenging fundamental models through a process of "idealized design," starting with the desired end and working backward to the goals and objectives in reaching it. There have also been more rigorous academic considerations of these topics, such as Decision Sciences by Paul Kleindorfer, Howard Kun-reuther and Paul Schoemaker,5 and research on organizational learning by Chris Argyris.6 Many other books and articles have touched in some way on mental models.

With so much having already been written on the topic, why another book? First, research in neuroscience is now supporting what we may have recognized intuitively in the past. This research makes mental models more substantial and, for us, more convincing, especially considering their inherent invisibility. Second, this book examines the impact of mental models more broadly, not just how they affect organizational decision making or learning, but the way they work and their implications for transformation—personal, organizational and societal. Finally, despite all that has been written about our mental models, the failure to see how they shape how we think and act is still leading to serious errors and missed opportunities. This is a lesson we can keep learning. This book represents an original take on the subject and an exploration of how these insights apply to personal and business life.

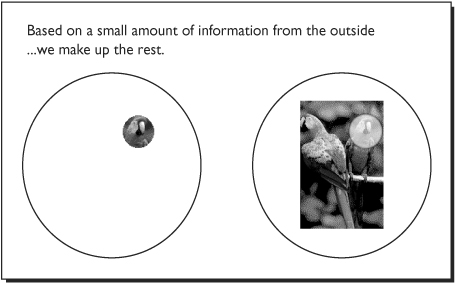

What We See Is What We Think

Whether considering a business move or a personal decision, what we "see" is not what we see (see sidebar, "The Difference Between Sight and Sense"). What we "see" is what we think. We usually trust what we see with our own eyes or perceive with our other senses. But research shows that we often use very little of the sensory information we take in from the outside world; most of it is discarded. Though we experience the process as seeing the external world, what the incoming stream of images actually does is to evoke other experiences from our internal world. This does not mean that the external world does not exist (although philosophers have argued this point), but only that we ignore much of it.

Most of what we see is in our minds.

The power of the mind in creating reality is demonstrated in the experiencing of a "phantom limb" by people who have lost a real limb through accident or surgery. The physical limb is no longer there, but the person continues to feel it. In a famous experiment, neurologist Dr. Ramachandran of the Salk Institute used Q-Tips®to touch a patient's face, evoking the reaction that he had just touched the patient's nonexistent hand. It turns out that the body map inside our brain has the hand and the face located in adjacent areas. When the hand was lost in an accident, the associated hand-mapping neurons moved into the adjacent face area for sensory input. The brain could now experience having its nonexistent hand touched. The person's experience of this touch was completely real. As Dr. Ramachandran observed in a series of lectures on the BBC, our brains are "model-making machines," and we construct "virtual reality simulations" of the world and then act upon them.7

While most of us have never experienced a "phantom limb," we have all had the experience of believing something and finding out suddenly that we were mistaken. This is the pivot upon which a magician's tricks often turn, as we are led to see a particular thing when, in fact, something quite different is actually taking place. Many of the great dramas and mysteries of fiction and of our own experience involve such twists. We are surprised and amazed by the shifts in how we make sense of the world.

The Difference Between Sight And Sense

The ability to make sense is different from the ability to see. Mike May, an accomplished downhill skier who had been blind since the age of three recovered some sight through an operation at the age of 46. In his diary, he describes the experience of seeing the world for the first time.8

On his first airplane flight with his newfound vision, he looked out the window but couldn't figure out what he was seeing. He thought the white lines he saw against the brown and green of the ground were mountains. He turned to the passenger in the seat beside him and explained his situation and asked: "Could you help me figure out what I am seeing?"

The woman sitting next to him explained that the white lines were haze, and then proceeded to point out the valleys, fields and roads in the scene below. When he later looked at the night sky with his new sight, he experienced the stars as "all these white dots, so many white dots" before truly recognizing them as stars.

The process of recovering his physical sight was just the beginning of the process of learning how to make sense of this new visual information.

The Importance of Mental Models

Mental models affect every aspect of our personal and professional lives and our broader society. Consider a few examples:

- Personal—Wellness. Every day, we are bombarded with new medical studies and other information. Some studies find that certain foods or activities have harmful or beneficial consequences. Some of these reports are contradictory. Even studies in respected medical journals are sometimes later overturned or found to be less conclusive than first touted to be in the media. We also receive other information about potential threats from diseases such as AIDS, mad cow disease, West Nile virus and SARS. How do we assess the danger and take appropriate action? We also face some more fundamental questions about our approach to health. For example, we can adopt the traditional Western focus on treatment of disease after it occurs, or we can focus on prevention of disease through diet, supplements and exercise. Or we can combine the two approaches. We can put our faith in allopaths, homeopaths, osteopaths or naturopaths. Our decisions in this area have a lot to do with how we make sense of the world. If we choose to adopt a diet to lose weight, we confront a cacophony of conflicting diets to choose from. The way we make sense of this picture has significant implications for our length and quality of life. How can we make sense of all these options? How can we become better at assessing the options and making decisions about our personal wellness?

- Corporate—Growth. Many companies have built their strategies around a traditional model of growth. Companies such as McDonald's, Coca-Cola and Starbucks have achieved growth in domestic markets and then sustained it by looking at overseas opportunities or new distribution channels. Other companies have grown through rollups and acquisitions. But the drive for growth has the potential to dilute the value of the brand—Star-bucks coffee has a completely different meaning when served in gas stations and supermarkets. Yet the commitment to investors often keeps these companies addicted to growth. How can companies create healthy growth strategies, which either enhance the brand (reduce churn, maximize lifetime value of customers, capture market share, enter new markets, add new distribution options, etc.), extend the brand to new product/markets, or create new brands (new growth engines)? What other models have companies used to build and sustain successful businesses? Could you apply them to your business?

- Society—Diversity and Affirmative Action. Mental models also play a key role in debates on challenges for our society. For example, what is the best way to address historical inequities in the treatment of ethnic minorities or other populations (such as women) that have faced discrimination? One model, embodied in U.S. Affirmative Action programs, creates a formal structure designed to compensate for historical discrimination. As President Lyndon Johnson explained in a speech at Howard University: "You do not take a person who for years has been hobbled by chains and liberate him…and then say 'You're free to compete with all the others' and still justly believe that you have been completely fair." But opponents of these strategies hold a different model—that programs such as Affirmative Action are in themselves discriminatory and tend to emphasize and thus perpetuate the very racism they are designed to counter. President George W. Bush called an Affirmative Action program at the University of Michigan, "divisive, unfair, and impossible to square with the U.S. Constitution."9The choice of these models has serious implications for legislation and society—and individuals. The competing views have played out in a series of high-profile court cases.

In each of these examples, mental models play a crucial role in our thinking and actions. Our models shape what we see, and this opens or limits our possibilities for action. We will explore some specific dilemmas of personal life, business and society in Chapter 11.

Thinking the Impossible

How do we engage in impossible thinking? The parts of the book that follow provide an overview of a process (see the sidebar, "Choices for Change").

First, we need to recognize the importance of models and the way they create limits and opportunities, as discussed in Part I. Then we have to find ways to keep our mental models relevant, deciding when to change to a new model (while adding the old to our portfolio of models), where to find ways of seeing, how to zoom in and out to make sense of a complex environment, and how to conduct continuous experimentation, as considered in Part II. Even if we are willing to change our thinking, we also need to recognize the walls that keep us in the old models, the confining influence both of the infrastructure and processes of our lives and of the slowly adapting models of those around us. In Part III we consider these obstacles to change and strategies for addressing them. Finally, we recognize that models are used in order to act quickly, and in the last part of the book we explore ways to access models quickly through intuition to transform our world.

Choices For Change

RECOGNIZE THE POWER AND LIMITS OF MENTAL MODELS

- Understand how models shape your world

- Recognize how models limit or expand your scope of actions

KEEP YOUR MENTAL MODELS RELEVANT

- Know when to shift horses

- Recognize that paradigm shifts are a two-way street

- See a new way of seeing

- Zoom in and out to make sense from complexity

- Engage in experiments

OVERCOME INHIBITORS TO CHANGE

- Dismantle the old order

- Find common ground to bridge adaptive disconnects

TRANSFORM YOUR WORLD

- Develop and refine your intuition

- Transform your actions

Endnotes

1. Mitroff, Ian I., and Harold A. Linstone. The Unbounded Mind: Breaking the Chains of Traditional Business Thinking. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

2. Brown, John Seely. "Storytelling: Scientist's Perspective." Storytelling: Passport to the 21st Century. <http://www.creatingthe21stcentury.org/JSB3-learning-to-unlearn.html>.

3. Russo, J. Edward, and Paul J. H. Schoemaker. Decision Traps: Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them. New York: Doubleday, 1989; Russo, J. Edward, and Paul Schoemaker, Winning Decisions: Getting It Right the First Time. New York: Doubleday, 2001.

4. Ackoff, Russell L. Creating the Corporate Future: Plan or Be Planned For. New York: Wiley, 1981.

5. Kleindorfer, Paul R., Howard C. Kunreuther, and Paul J. H. Schoemaker. Decision Sciences: An Integrative Perspective. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

6. Argyris, Chris. On Organizational Learning, 2d ed. Blackwell Publishers, 1999.

7. Ramachandran, Vilayanur S. "Neuroscience: The New Philosophy." Reith Lecture Series 2003: The Emerging Mind. BBC Radio 4. 30 April 2003.

8. Sendero Group, "Mike's Journal," March 20, 2000, <http://www.senderogroup.com/mikejournal.htm>.

9. Greene, Richard Allen. "Affirmative Action: History of Controversy." BBC News World Edition. 16 January 2003. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/2664505.stm>.