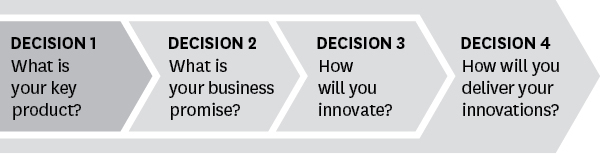

Decision 1What Is Your Key Product? |

Imagine you’ve been offered a job running an important subsidiary of a major company. You’ll be expected to deliver a profit year after year even though you can’t change anything—nothing at all—about the one key product your organization produces. Not only that, but if you were to start turning out a better product, the parent company would reach down and take your best assets. Would you accept that job?

You might if you were a baseball fan. This is exactly the challenge faced by the general manager of the Lehigh Valley IronPigs, a Triple-A farm team of the Philadelphia Phillies. The IronPigs—the name refers to molds used in making steel—have figured out how to succeed under those conditions. Between 2008—when they began playing in a new ballpark—and 2015, they have filled on average over 80 percent of the ballpark’s total seating capacity, fixed and temporary, for each of 423 regular-season home games.

How have they done it? Through the Third Way. They can’t innovate in their core product, a professional baseball game with its immutable set of rules, so they’ve had to attract fans by innovating around the game.

By coming up with inventive promotions, novel merchandise, and entertaining stunts, the IronPigs have made a compelling proposition of what has often been a subpar product. Despite a steadily declining record over the last three years, fans return year after year.1 In fact, the Lehigh Valley IronPigs have the highest average attendance of any club in the minor leagues, despite playing in one of the smallest markets. Examples of promotions and stunts include giving away foam fingers on Prostate Cancer Awareness Night (remember, their fans are mostly men) and free funeral services on Celebration of Life Night. They were the first team in North America to adopt a video game system called Ski the Piste in which the user of a urinal guides a skier down a slope, avoiding fences and aiming for penguins.* FoxNews.com ranked IronPigs fans the best among all minor league baseball teams.2

Large organizations typically don’t have to live with the stringent constraints the IronPigs face. Most firms have the resources and freedom to innovate wherever and however they want. Given that autonomy, it seems counterintuitive to ask them to begin an innovation program by specifying where they will not innovate.

But a quick look at the companies we’ve already discussed reveals that this is precisely what they did, even in the face of competitive threats. CarMax’s key product was late-model used cars, and Apple’s was PCs, at least in the late 1990s.3 LEGO, in fact, almost went out of business when it tried to innovate away from its key product, plastic-brick-based construction sets. Only when it returned to the brick—but in a new way, surrounded by complementary innovations—did it go on to renewed success.

In this chapter, we will first describe key products in more detail—what they are and the considerations you should keep in mind as you pick them. Then we will describe, once you’ve picked a key product, what you must do to prepare it for Third Way success.

Choosing a Key Product

Choosing a key product is a decision to focus on that product, to honor it, and to build around it. It sends a signal to the organization that this product and its customers will be a central focus of effort in the months and years to come. It’s also a strategic decision about the type of innovation you won’t be investing in: you won’t be creating new products that will conquer new markets, and you won’t be using “disruptive” technologies to create revolutionary new products that replace existing ones. Instead, choosing a key product is a decision to keep that key product essentially the same and to build a portfolio of complementary products and services around it.

Because a key product or service will be the stable foundation on which you will build an entire system of interrelated innovations, it needs to be chosen with care.

What Qualifies to Be a Key Product?

A key product is any product you’ve chosen to make more appealing by building a system of complementary innovations around it. Designating a key product is often an easy, straightforward decision, an obvious choice, especially for firms with a strong brand. It’s the business you’re in, what your customers have come to expect from you. It’s what your firm did yesterday, does today, and most likely will do tomorrow.

While we’ve said it can be any major product or product line, a strong key product usually passes the following six tests:

Is it a product that is or could be central to your company—something that defines or helps define you and what you do? Is it something customers can link with your company and your brand? Will it build or reinforce your company’s strategic identity? Will selling it take you toward your strategic goals? Will it build your presence and brand in your company’s existing markets or some future market it seeks to enter? In short, is it a good fit with your firm—with what your organization does, how it’s seen, and where it wants to go?

Does or could this key product appeal to a distinct and sizable set of customers? The most successful key products appeal, or could appeal, to an important market segment. Without a clear target market, you will have difficulty identifying the needs that the product and its complementary innovations will meet. Such a clear set of needs is the basis for selecting a strong promise and identifying innovations that fulfill that promise (decisions 2 and 3).

Does or could the key product exist more or less autonomously? Or is it somehow tied to another product? For example, it wouldn’t make sense for Apple to designate its iTunes Music Store as a key product because it exists only as a complementary innovation that works with and supports Apple’s other products such as iPods or iPhones.

Is the key product a stable product? Is it likely to remain essentially unchanged—that is, undergo nothing more than incremental improvements—over at least the next few years? It would make little sense to build a system of complementary innovations around something that will itself undergo significant change in the foreseeable future.

Does the key product draw on and reflect the strengths and values your company is known for? Circuit City chose to launch CarMax largely because selling used cars was a sizable retail business where no one had yet applied the deep expertise in retailing that Circuit City possessed. Apple was virtually alone among computer makers in its ability to make hardware and software work together. By that time in the short history of personal computing, all major companies focused on either hardware or software. Because Apple retained expertise in both, it was able to create a uniquely seamless computing experience for the user. Almost everything it did in pursuing the Third Way reflected and drew on this distinctive capability.

Could the product and its complements generate significant revenues? Handled properly, surrounded by the right complementary innovations, could your key product and its family of complements generate enough profits to justify the effort and resources devoted to them?

All these questions might be summed up very simply: does the product you’re considering have the potential for higher sales, and if it produces higher sales, will those sales take your company closer to its strategic goals?

Identify the Key Customers for the Key Product

Once you’ve identified the key product you wish to innovate around, the next step, a critical one, is to identify the key customers for your key product and why they buy it. The story of Gatorade in chapter 1 perfectly illustrates this indispensable task.

Before Sarah Robb O’Hagan’s arrival, Gatorade had been pursuing the often-misguided course we see many companies follow, especially when the growth of an important product has flagged. Product managers search for new customers by spinning out new product variations and new ways and places to market them. Every new variant costs more but sells less. The result may be an increase in sales, but that increase comes with declining profits. Even worse, in their efforts to reach ever more customers in every conceivable market segment, managers lose sight of the segments with the most loyal customers. As they reach for everyone, the product loses its specific and enduring attraction for its most loyal customers.

The decision of Robb O’Hagan and her team to focus on serious athletes took courage. It meant abandoning all those casual customers PepsiCo had added with more product versions and mass distribution. To others at Pepsi, it must have looked as if Robb O’Hagan’s response to falling sales was to target a smaller market—not an obvious route to success. To grow sales that way meant selling more to each customer. And that was what she and her team did by adding nutrition products—complementary innovations—around the drink. With those additions, Gatorade, or G, could satisfy a compelling need of serious athletes: it provided the “sports fuel” they needed for peak performance.

The key lesson of Gatorade’s turnaround is this: when selecting a key product, choose as well the key customer segment—a “beachhead” set of customers—on which you will concentrate your initial efforts to sell the product. Focusing on that segment and discovering its specific needs will lead you to a more compelling promise, and a more compelling promise will guide you to the most compelling portfolio of complementary innovations that surround the key product. After that initial group of customers has been satisfied, you can expand out from there to additional groups. But the more vague and broad the definition of that initial group of customers, the more vague and unconvincing the promise and all that follows from it will be.

Everything Robb O’Hagan and her people did to turn around Gatorade flowed naturally from their choice of serious athletes as the target customer.

Some Don’ts in Choosing a Key Product

Don’t dismiss legacy products. Surprisingly, though the key product in many companies is easy to identify, it no longer commands much attention and respect. It’s the old, boring product line that supplies the profits that fund the company’s exciting new ventures. Sometimes those old products really are on their way out. But maybe, though, that tired legacy product can be more than just a cash cow. Maybe the Third Way can infuse it with new purpose and life. LEGO thought construction toys based on the plastic brick had seen their day, until it discovered how to revive them for a new generation.

Don’t reject a key product candidate just because it’s not profitable. This advice may sound odd, but many key products don’t make money for the companies that offer them. They’re key products because they lead to the sale of other profitable products or services. Auto companies, for example, have been described as manufacturers that make a product that they sell for essentially zero profit in the hopes of getting the financing revenue. Printer makers may sell their product for little or no profit in hopes of selling pricey ink cartridges.

Don’t overlook the possibility that a key product may not be yours. This situation is unusual, but there are companies that thrive by selling the complementary innovations that surround someone else’s product. To extend the previous example—there are companies that sell discount toner and color cartridges for someone else’s printers. Logitech sells accessories—Bluetooth keyboards, laser presentation pointers, mice, and the like—for PCs made by others. Dunhill, the British luxury goods company, began life a century ago by selling “motorities”—accessories such as driving gloves, goggles, horns, and luggage for owners of the then-new automobile.

Don’t reject a product because it’s struggling in the marketplace. Many companies have turned flawed products into great successes not by improving the products themselves but by surrounding them with the right complementary innovations. CarMax suffers from a purchasing disadvantage with its competitors. LEGO’s bricks are far more expensive than competitors’ versions. And Novo Nordisk was late to the HGH market with a me-too product.

Can a Company Have More Than One Key Product?

Avoid the self-limiting mistake of thinking a key product can only be your firm’s most important and strategic product or product line. It may be that, and it certainly was for the IronPigs, CarMax, LEGO, Gatorade, and Apple. But it needn’t be. For Novo Nordisk, its HGH therapy drug, Norditropin, was secondary to the company’s main line of insulin and other diabetes-related products. Still, Norditropin was an important new product with great potential that could only be differentiated by the innovations surrounding it.

If your company is organized around multiple strategic business units or divisions, you should think about key products in the context of those units, rather than the firm as a whole. For example, a car company may, and probably should, consider its family sedans, pickup trucks, and sport coupes separate key products (actually, product lines) because they attract different buyers and the complementary innovations that appeal to each set of buyers are likely to be different.

The possibility of multiple key products raises an important question, however. Can you have too many key products, each with a different system of complementary innovations? The answer is yes. Each system will require real time and effort from people across the organization. At some point, the total effort will become too onerous for the firm as a whole. Too many key products can become what Jim Collins calls “the undisciplined pursuit of more,” which can lead to a loss of focus on the products and customers that are truly important.4

A Key Product Can Change over Time

We’ve emphasized that a key product is where you will not focus any major innovation efforts. Those efforts will go, instead, to the creation of complements around the key product that make it more attractive. Two exceptions to this general rule deserve comment.

First, you can and should continue to make sustaining, incremental improvements to a key product as long as the changes aren’t significant—that is, as long as they don’t diminish the product’s ability to work with the complementary innovations surrounding it. This point may seem obvious, but some change in a competitive product or some other move by a competitor may tempt you to respond in kind. When AutoNation threatened its very existence, CarMax could have followed by adding new cars to its product line or by acquiring existing dealers to expand rapidly. But both those options would have led it to abandon its original approach. In the end, CarMax prevailed by continually improving its approach without changing it fundamentally.

Second, a key product and its complements can change because of market response. When Apple released the original iPod in 2001, it was a complementary innovation intended, with iTunes, to drive sales of the Mac computer, which would be the hub of a user’s digital life. But that approach changed dramatically in 2003, when Apple launched iTunes for Windows, which effectively made the iPod a key product rather than a complementary innovation. With the later release of the redesigned iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad, those too joined the Mac as key products. Customers could use one or all of them to help manage their digital lives. In 2016 the iPhone, which began almost as an afterthought, an accessory designed to sell more Macs, provided over 60 percent of Apple’s revenue.5

Preparing a Key Product for Success

Picking a key product is the first crucial step in pursuing the Third Way. But before proceeding to decision 2 (choosing a promise for the key product) and beyond, you must take some further steps in decision 1 to help ensure success. Selecting a key product is akin to doubling down in blackjack, a process where you double your bet, limit your ability to take new cards, and—if done intelligently—increase your chances of winning.6 Just like doubling down, choosing a key product means you’ll be betting more on less, so you should be sure that this decision is made decisively and transparently and that you communicate it widely through your organization.

Identify the Key Product and the Approach Clearly

Because the Third Way will involve so many people across your organization, it’s important to begin by consciously and clearly communicating to all involved inside and outside what you’ve done and what it means. At this stage, you need to communicate three messages consistently.

You need to explain that the product you’ve chosen will receive special attention. If this product is not the company’s core product or an obvious candidate for attention, you also need to explain why this product was chosen—that is, why you think an opportunity exists to increase its sales.

You should describe how most innovation efforts will be focused not on the product itself but around it in the form of complementary innovations that make the product more appealing. Otherwise, people will naturally assume that innovation efforts will focus on the product itself.

Finally, explain that those complementary innovations will come from across the organization and from outside partners, not just from people in product development and marketing. It’s important for all groups to know that they can and should play a role.

Make the Key Product Lean and Trim

You may have noticed that every company we’ve described so far—except for Novo Nordisk, whose HGH drug was a new product—took the same step early in the process. That is, they all rationalized and trimmed the product line they’d just selected as a key product.

Steve Jobs eliminated dozens of Mac models that had been added to the line haphazardly. In focusing on serious athletes, Sarah Robb O’Hagan cut back drastically the number of flavors and variations that Gatorade had added in its quest to become a mass market beverage. LEGO, when it returned to the brick, cut its inventory of shapes and colors in half. And CarMax, after deciding to sell used cars, trimmed its product line even further to focus only on late-model used cars.

What makes all this culling necessary is simple, though possibly painful: if you’re going to develop complementary innovations, you will need to coordinate different innovation efforts across diverse groups. That becomes much more difficult if your key product is complex and confusing and its target customers no longer well defined or understood. Also, by reducing the money-losing proliferation of product variants, you will free up resources to invest in complementary innovations.

Make the Key Product as Strong as Possible

As you focus your innovation efforts around a key product, people may assume that all efforts to improve the product itself should cease.

So it’s important to be clear: a key product must be as strong as possible. Make sure its production, delivery, sale, and distribution processes are as efficient and effective as possible. When CarMax identified newer used cars as its key product, it worked hard to be better than anyone else at knowing which cars to buy, at what price, in the wholesale market.

When Apple reduced its product line to four Mac models, it began work on a better operating system. It also increased quality and cut costs by outsourcing manufacturing and completely reworking its supply chain. Similarly, when LEGO returned to the brick, it reworked its supply chain and outsourced some manufacturing operations.

The Challenges of Decision 1

Decision 1 can seem so simple and self-evident that you might think making it can be done quickly. This is sometimes the case, but take care to get your key product or service clear, focused, and strong. If you don’t, you won’t be able to get the subsequent decisions right. Everything else depends on it.

Though it can seem simple, making decision 1 can in practice offer certain challenges. The first, which we described in chapter 3, is that the choice of a key product, the choice of key customers for that product, and decisions around culling a product line can create winners and losers inside your company. Thus, it’s important that you make these choices in ways that are both inclusive and open. By inclusive, we mean a process that gives full and thoughtful consideration to all product candidates, so that supporters of “losing” products, though disappointed, will feel they’ve been heard and the process was fair. By open, we mean a process in which all involved know from the beginning how and by whom these choices will be made.

The second challenge in decision 1 is that making any important product off-limits to change can cut against the grain of today’s thinking about innovation, thinking that says everything should be considered a candidate for drastic change. Conventional wisdom says that the best response to a significant threat is to radically change yourself. But we’re saying, before you do that, you should first ask, “Do we really need to fundamentally change our important products or services?” Often the answer is no; what’s needed is to return to, honor, and build around the product or products that made your company great. Focusing on one or a few key products takes courage and discipline, but many companies have succeeded by doing it well.

When you’ve completed decision 1, you will have identified the key product—the product around which you will focus your innovation efforts, you will have identified the key customers for that product and you will have made that product line as trim and strong as possible. In chapter 5, we will take you through the next step: identifying the promise you will make to your customers—the promise that the key product and its family of complementary innovations will satisfy.

Three Takeaways for Chapter 4

![]() The Third Way begins, first, by clearly identifying the key product around which you will create a family of complementary innovations and second, by identifying the “beach head” customer segment—the group at whom you will target the key product.

The Third Way begins, first, by clearly identifying the key product around which you will create a family of complementary innovations and second, by identifying the “beach head” customer segment—the group at whom you will target the key product.

![]() A key product should be stable, strategically important for your company, and capable of generating sizeable revenues. It should be a product that you produced yesterday, are producing today, and will continue to produce tomorrow.

A key product should be stable, strategically important for your company, and capable of generating sizeable revenues. It should be a product that you produced yesterday, are producing today, and will continue to produce tomorrow.

![]() The first step for many companies after selecting a key product will be to trim and strengthen that product. Unnecessary product variants should be culled and innovation efforts refocused on the development of complementary innovations.

The first step for many companies after selecting a key product will be to trim and strengthen that product. Unnecessary product variants should be culled and innovation efforts refocused on the development of complementary innovations.

* In spite of what it seems to mean in this context, piste is French for “ski trail.”