Decision 4How Will You Deliver Your Innovations? |

|

Thus far, you’ve chosen your key product; defined a clear, compelling promise; and designed a portfolio of complementary innovations that deliver the promise. Now you must bring those complementary innovations to market by deciding who will do each and how you will deliver the entire project.

In this chapter, we will discuss the challenges raised by decision 4 and how to deal with them. For that purpose, we will focus on the critical role of the manager leading a Third Way project. Get that role right, and many of the other problems will become manageable. Get it wrong, and your Third Way project is probably doomed.

We begin with the story of Guinness, the Irish brewer, and what it did to execute decision 4 well.1

Guinness and Irish Pubs

In the early 1990s, managers at Guinness noticed something unexpected: a spike in demand for Guinness beers in diverse markets and communities across Europe. Higher sales were showing up even in places like Germany, France, Italy, and Switzerland, where no one had anticipated much, if any, growth.

When Guinness managers looked into this welcome development, they discovered that much of the growth was coming from areas where successful Irish pubs were located. The growth was coming not only from the pubs themselves, but also from bars and restaurants around the pubs. Clearly, the Irish pubs were introducing local drinkers to Guinness, and those drinkers were asking for it wherever they dined or drank.

At the time, 90 percent of Guinness draft beer was sold in Ireland and the United Kingdom, and so Guinness managers sensed an opportunity to expand their market. But how to repeat those local successes? The company was a brewer, not a retailer. Trying by itself to create a network of Irish pubs around Europe and elsewhere would require a huge, risky investment in a part of the business Guinness knew virtually nothing about.

Wisely, the company’s first step was to send a team of designers, restaurateurs, marketers, and real estate people to study the pubs.2 After looking at some seventy or eighty establishments, the group reported its findings.

Most of the pubs were the genuine article—real Irish pubs that faithfully replicated the great mid- and late-Victorian pubs of Dublin and Belfast. Their owners had made significant investments in the pubs’ design. In fact, they had bought the millwork—doors, window casings, cabinets, back bar and mirror, and other signature components—from Irish firms where artisans plied a unique two-hundred-year-old craft. The pubs also served food, including Irish dishes prepared with fresh, local ingredients.

While most of the pub owners were not Irish, many had family ties to Ireland and most had visited Ireland and studied Irish culture. Above all, they understood how to create the warm, friendly atmosphere that made real Irish pubs uniquely and universally appealing.

Eager to grow the number of Irish pubs in Europe and elsewhere but unprepared to open pubs itself, Guinness chose an approach, which continues today, that grows the number of pubs by helping others open them.3 First, it identified in Ireland the critical expertise that independent owner-operators would need to create a genuine Irish pub. Second, it created an initiative inside Guinness, dubbed the Irish Pub Concept, that would mentor prospective owner-operators through the process of building, opening, and operating successful pubs.

Each of the design-build firms that Guinness identified in Ireland starts work on a new pub by helping the owner choose the right location for the pub and the pub’s layout. Authentic Irish pubs aren’t rectangular blocks; they twist and turn so that the customer discovers new rooms around every corner, including a back bar—an important component of any true Irish pub. Then it lets the new pub owner choose which style of pub he or she prefers—country, Celtic, or Victorian, for example—and completes the design specifically for the site where it will be located. Then the firm builds the pub in an Irish warehouse, disassembles it, loads it into a shipping container, and reassembles it on site.

Guinness also identified hospitality consultants, food service equipment companies, real estate professionals, architectural consultants, and site selection experts—in short, a pool of know-how and experience that owner-operators can tap as needed. Finally, it helps the new pub owner find young adults with red hair, freckles, and Irish accents who will go work in the new pub.

It’s an informal arrangement. Guinness itself pays nothing to members of the pool; nor are there any contracts linking Guinness and the other firms (although the woodwork in most pubs has “Guinness” carved into it somewhere). The entire venture now exists outside of Diageo Guinness; each firm belongs because it benefits from belonging.

The second major piece of the Irish Pub Concept is the mentoring of prospective pub owner-operators. Because the concept cannot succeed unless the pubs succeed as stand-alone businesses, the Irish Pub Concept helps new owner-operators in several ways.

It works with each of them to ascertain if opening a pub is the right thing for them to do. Part of that determination hinges on their ability to make the substantial investment required. While Guinness and the Irish Pub Concept don’t directly involve themselves with financing, they will connect prospective owners with banks and help the owners prepare the plans and projections banks need before making a loan. Once financing is in hand, consultants work step-by-step through the entire development process with each owner—some three thousand steps, in fact—to make sure everything is done in a proper and timely way and to help each owner avoid the mistakes new restaurateurs often make. The consultants also provide training in every aspect of running a successful pub. The training program, appropriately, includes a pub crawl around Dublin.

People from Irish Pub Concept and the design-build firms have traveled throughout Ireland, observing hundreds of pubs to understand how they, though they’re all different, create the welcoming, convivial atmosphere that transforms a pub into a genuine Irish pub. Creating this magic, they’ve found, comes from imbuing each pub with its own quirky authenticity—in the way it’s laid out, its architectural details, its millwork, the way it’s run, and even in minor but essential touches like real photographs and bric-a-brac from Ireland.

Key to that authenticity is the personal story that the design-build firm helps the owner create. It’s the story of how that specific pub, its site, and its owner are somehow linked to Ireland—for example, through the history of Irish immigrants in the area, the owner’s family history, or something similar. That story is then told in various media throughout the pub. An image from the story might appear in a stained-glass window, an old photograph, or the millwork or artwork created just for the pub.

In all these ways, each pub is both unique and similar. None is a duplicate of another. Yet each, when done right, captures the spirit of Ireland as a place that is warm, open, and welcoming, a place where complete strangers find themselves talking, a haven from the friction and turmoil of the world outside. Guinness benefits by linking its beer with the appeal of the pub. Those who drink it there return again and again, and they order it in other eating and drinking establishments when they seek to re-create at least a piece of the pub’s conviviality.

The Irish Pub Concept has paid off for Guinness. Over a period of six years, some twenty-five hundred Irish pubs opened in Europe, increasing annual sales of Guinness draft beer throughout Europe by about half a million barrels. Where only 10 percent of Guinness draft beer was sold outside Ireland and the United Kingdom before 1990, the share has now increased to 32 percent.

As Donal Ballance, a former senior manager at Guinness who was involved in this venture, said, “If you want to make your brand come alive, the best way you can do it is to build a shrine around it. That’s what the Irish Pub Concept did for Guinness.” It’s hard to think of a better way of describing how the Third Way works. By creating a system of new ventures that worked to the advantage of all players, Guinness achieved the distinctive benefits of this approach: low costs, low risk, and high returns.

The story of Guinness and Irish pubs highlights the benefits and perils of decision 4, where all your prior work comes to fruition. The benefits for Guinness were more customers and higher sales. The perils were perhaps less obvious, but they were real nonetheless. They arose from the fact that executing the Third Way often takes you far away from what your company is good at doing. For Guinness, the challenge was that the complementary innovation it chose—opening Irish pubs throughout Europe—had to be done largely outside the Guinness organization. Owner-operators had to be found, design-build firms identified, and myriad sources of other expertise located.

Guinness wanted to set up and manage that unfamiliar work, though nothing in its long history as a creator, brewer, and marketer of beer had prepared it for such a challenge. Though it understood its end consumers quite well, it possessed little expertise in architecture, financing, construction, hiring, running a successful restaurant business, and the many other skills needed to build and manage an Irish pub.

Problem: Leading a Third Way Project through an Existing Innovation Process

Many leaders try to pursue the Third Way, but their organizations stumble when they get to decision 4. The reason is that most companies have designed their internal roles, metrics, and processes to support and encourage more of the same—that is, incrementally better versions of current products or new variants of current products for new market segments.

Those roles, metrics, and processes are designed to reduce the risk and increase the success rate of such new product development ventures. But will they work when you’re developing a complementary innovation that’s not more of the same?

Try this thought experiment. Turn back the clock and imagine that you work for Guinness in the early 1990s, and the company has decided to develop the Irish Pub Concept internally using the same system it has used for decades to develop successful new beer varieties. You are the product manager who has developed many of those varieties, and you’ve just been challenged to grow Guinness sales in Germany by developing a new beer specifically for that market.

You and your group do field research and discover that Guinness sells better in German neighborhoods that have Irish pubs. In fact, you meet individuals in your research who express interest in investing in and owning an Irish pub. You return to Dublin convinced that, to succeed in Germany, Guinness needs both a new beer variety and a program that fosters Irish pub ownership across the country.

You make a presentation to Guinness leaders, and you convince them to go forward with both the new beer and the German pub program. Their approval initiates the company’s well-established process for managing innovation, which is essentially a series of stages. At the end of each, you will report on your progress, and if the leaders are happy, they will allow you to proceed to the next stage. This is the tried-and-true product development process the company has used for many years with good results.

Now think about how this project might unfold:

![]() You, the product manager, are an experienced and respected leader. But you know nothing about building a pub, and so you will have to find and work with outside experts. You’ve never had to do that before in your role. Even more problematic is that you, in your product manager role, have no authority to reach out and form partnerships with outside architects,

You, the product manager, are an experienced and respected leader. But you know nothing about building a pub, and so you will have to find and work with outside experts. You’ve never had to do that before in your role. Even more problematic is that you, in your product manager role, have no authority to reach out and form partnerships with outside architects,

![]() You are given a team of experienced, dedicated, and smart people to work with you on the pub concept, as well as extra part-time support from the business development, legal, and finance departments. But the team members you’re given also know nothing about building and launching a pub or about forming partnerships with outside firms that do know. Many team members, in fact, have never before been asked to innovate in this way. And the supervising management team that you report to lacks the knowledge and experience needed to provide you and your team the support and guidance you need.

You are given a team of experienced, dedicated, and smart people to work with you on the pub concept, as well as extra part-time support from the business development, legal, and finance departments. But the team members you’re given also know nothing about building and launching a pub or about forming partnerships with outside firms that do know. Many team members, in fact, have never before been asked to innovate in this way. And the supervising management team that you report to lacks the knowledge and experience needed to provide you and your team the support and guidance you need.

![]() The company’s standard product development process requires that you develop a detailed business case, outlining the investments required, the profits expected, and the timeline for the various outlays and income. Your business case is now split into two: one for the beer and one for the pubs. The business case for developing a new beer is straightforward and familiar. You know the investment required, the risks, the marketing costs, and the potential payback. But the business case for the pubs is much more difficult to construct. You’ve found prospective owners who will invest in the first few pubs, but you know that additional investment will be needed to build a program that encourages more owners to open pubs in the future. You suspect that management is unlikely to invest the company’s limited funds in this project at the expense of others with better, faster, and lower-risk returns.

The company’s standard product development process requires that you develop a detailed business case, outlining the investments required, the profits expected, and the timeline for the various outlays and income. Your business case is now split into two: one for the beer and one for the pubs. The business case for developing a new beer is straightforward and familiar. You know the investment required, the risks, the marketing costs, and the potential payback. But the business case for the pubs is much more difficult to construct. You’ve found prospective owners who will invest in the first few pubs, but you know that additional investment will be needed to build a program that encourages more owners to open pubs in the future. You suspect that management is unlikely to invest the company’s limited funds in this project at the expense of others with better, faster, and lower-risk returns.

![]() As you construct a project plan, you realize that the pub concept will take much longer to develop than the new beer. You present your plan to management and argue for an expansion of the plan and more time. But you’re still given a very tight time frame to both develop the beer and launch the first pub. That’s a problem because growing the number of Irish pubs in Germany will take much longer than developing the beer, and your business case for the success of the beer depends on a boost of sales from your new pubs.

As you construct a project plan, you realize that the pub concept will take much longer to develop than the new beer. You present your plan to management and argue for an expansion of the plan and more time. But you’re still given a very tight time frame to both develop the beer and launch the first pub. That’s a problem because growing the number of Irish pubs in Germany will take much longer than developing the beer, and your business case for the success of the beer depends on a boost of sales from your new pubs.

This is, of course, an extreme example. Guinness didn’t even think about trying to develop the Pub Concept this way. But we suggest this thought experiment because it illustrates the pitfalls that are harder to see in less extreme settings. It’s obvious that Guinness would have failed if it had tried to treat the Pub Concept as if it were a new beer. But this approach, unfortunately, is what many companies try to do. They have one process for innovation, and they put every innovation project through that process. The result for a Third Way initiative is almost certain failure.

The goals of a traditional product development process—to manage risk, reduce the cost of development, and increase the probability of success—are still the right goals. But a portfolio of complementary innovations must be developed differently, by different people, and judged by different standards because it will deliver benefits to the

organization in a different, more complex way.

A New Leader for a New Approach

The starting point for any Third Way project is to recognize that the conventional methods and techniques most companies have always used won’t work anymore. To succeed, the Third Way calls for a different approach, and a different approach calls for a different kind of leader. A traditional product manager cannot do this job. What’s needed is a new leader who has the right mandate, as well as the right tools, for the job.

A New Mandate for the Project Leader

When a company designates a key product, it must also name a project leader who will manage all the innovation efforts around it. Most companies assume––mistakenly––that this person should be the traditional product manager responsible for the product.

To understand the problems this approach can create, look again at the GoPro story, but now look at it from inside a key competitor. When Sony saw GoPro emerge as a serious competitor, its executives challenged product managers in Japan to produce a “better” action camera.4 The product development team succeeded by producing an action camera that was superior in several dimensions: more pixels, image stabilization, better GPS, and a third lower cost. Unfortunately, it was a case of winning the battle—a better camera—but losing the war. GoPro still sold many more cameras. Why? In spite of a better camera, Sony still lacked good mounts, a good smartphone app, PC software, and a good social media site—all crucial complements that helped customers capture their adventures.5

Sony product managers succeeded with the goal they were given. But that goal was based on the traditional definition of a product manager’s role—to focus solely on the product itself. In setting that narrow goal, Sony leadership focused on beating the competition rather than “dating” the customer. Sony didn’t support what the customer was trying to do with the camera. This is how product managers are set up to fail when the situation calls for the Third Way. If they are limited to the traditional goal of producing “a better product,” as the Sony product managers were told to do, they can succeed in achieving the goal while simultaneously losing the market.

The scope of the project leader’s authority is crucial. Defining that role too narrowly can kill any chance of Third Way success, because, as we suggested in chapter 3, this approach calls for a higher-level role, a solution integrator. The most important responsibility of the person in this role is to create and lead a cross-functional team that is separate from but connected to the hierarchy. The job of the leader and team is to spearhead the cross-organizational process of working through the four decisions: designating a key product; finding the strongest possible promise for that product; selecting, specifying, and designing a complete set of complementary innovations around it; and then choosing and managing, inside and outside the company, those who will deliver the innovations.

Mindset is critical throughout this process. The leader and team need to be guided by a deep understanding of the customer and the context in which the customer uses the product. What is the customer’s entire experience of, first, sensing a need for the product and then finding, acquiring, and using the product? What will it take to make all parts of that process work better? What more can be done to help the customer solve the entire problem he or she is trying to solve when buying the product?

The Third Way can only succeed if the solution integrator and team possess the ability, mindset, and mandate to lead both a companywide effort and outside partners as well. And it can succeed only if the leader and team are held responsible not just for developing or improving a product but also for helping the customer get value from the product, even if success requires the leader and team to take steps that reach across the organization.

Does this mean you should eliminate the role of product manager? On the contrary, decisions about allocating product development resources will become even more complex, and there’s still a strong need for someone to manage the product and ensure that it has the necessary features and quality. But this role is no longer the final decision maker about the product. The allocation of development resources will be based on the needs of internal and external customers. Partners developing complementary products will need information and support, and the person managing the development of the key product will be as busy as ever.

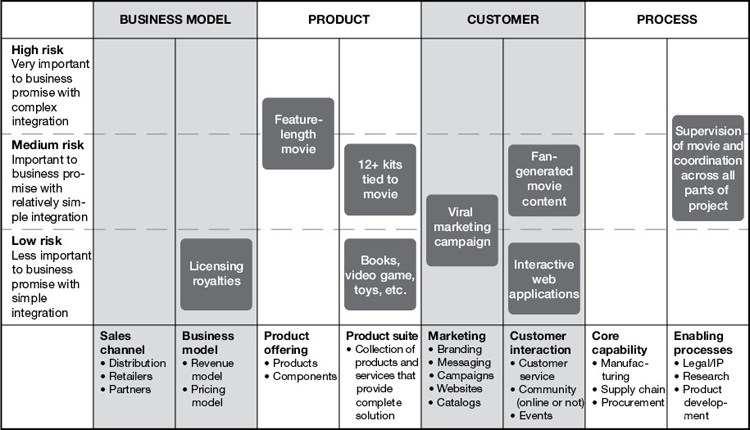

Table 7-1 summarizes the key differences between the old role of product manager and the new role of solution integrator.

The evolution of the Third Way product leader: from product manager to solution integrator

| Product manager responsibilities | Solution integrator responsibilities |

|

|

|

If the Sony product managers had been given the right mandate and authority—to meet the needs of adventurers who wanted to record and share their greatest accomplishments—the outcome might have been much different. Those managers and their teams were probably doomed to failure before they started, by the structure, process, team members, and goals that they were given.

Because it’s so vulnerable to such organizational issues, decision 4 differs from the other decisions in that it begins early and continues throughout the project. Decision 4 is a set of interlocking smaller decisions, all of which will begin to get made very early in the project, but many of which will not make their effects known until much later. In other words, bad decisions made early can doom a project later.

One of the most important responsibilities of solution integrators and their teams in these early stages will be to prepare management, team members, and, later, outside partners for the new challenges of the Third Way. For this purpose, the solution integrator and his or her team will need to create simple, early versions of the overall project specification, business plan, and project plan. These will be revised and expanded as the project moves into decisions 3 and 4.

The project specification defines the product, complementary innovations surrounding it, and expected project outcomes. While many of the documents that make up the project specification are familiar to innovators, we recommend adding a new one—the innovation matrix, described below—which will help summarize and communicate the project and its goals.

The business plan makes financial projections of income, investments, variable costs, and projected profitability for the project. Most companies have specific methods and formats for computing a project’s projected revenues and costs. But as with everything else about a Third Way project, there are a few differences in the way a team should construct its business plan, differences that can make or break a project. We will discuss these differences below.

Finally, the project plan lays out who will do what, when, to achieve the expected outcome. This is a more straightforward exercise. While a project plan is never simple, if a project team has done the other steps carefully, the planning should not be different from the planning done for any other large, complex project.

In the sections below, we’ll talk about project specifications, business plans, and project plans for Third Way projects. The goal, as in other parts of this book, is not to review existing and well-understood material but to show where a different approach will prove useful.

A New Leadership Tool: The Innovation Matrix

Every innovation project needs a clear statement of tasks and deliverables, and a Third Way project is no exception. With traditional product development, the structure and contents of early deliverables for the product—customer needs, product specifications, product costs and price, and investment targets—are usually well understood. As a company makes the transition to the Third Way, however, it will need to create an additional set of deliverables that cover both the key product and the multiple complementary innovations around it. Many of these deliverables will be straightforward adaptations of existing templates. But two in particular will be different for the Third Way—the overall project plan and the business case. First, the project plan.

In February 2014, LEGO released the company’s first full-length animated feature film with the LEGO brand attached. While LEGO had worked with outside groups to create direct-to-video movies and episodic TV shows, it had never put the company’s name on a full-length feature film. Another major challenge of the movie was that it was done using an entirely new type of computer-generated animation, in which every scene was made to look as if it were created with real LEGO pieces. This type of animation represented a huge technical challenge—creating waves in a sea of blue LEGO bricks, for example, was no small feat.

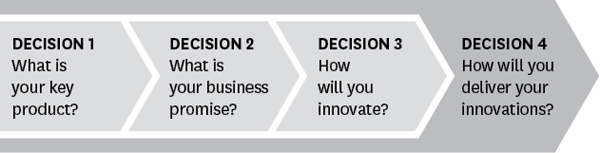

To track the different parts of this Third Way project, LEGO would have used the innovation matrix (figure 7-1), a project management tool it developed internally. The innovation matrix lets a team track and coordinate the different components of a project and their associated levels of risk.6 It’s a project management and communication tool used to ensure that every part of the project is coordinated well and completed on time. Here is how LEGO might have used this powerful tool to produce The LEGO Movie.

A sample innovation matrix for The LEGO Movie

Note: “IP” stands for intellectual property

No two companies will create the same matrix. The unique nature of the key product at the center of the project will drive the definition of the categories. But the overall structure of the matrix should be the same: the horizontal axis is a set of business categories that define the different types of innovation. These different categories should be structured so that they correspond to the different functional groups in the company. The vertical axis shows the risk level of each innovation in the project. The result is a one-page description of the total project.

The first step in building a matrix is to define the horizontal axis—the different types of innovation. These types fall into four general categories. Left to right in the matrix shown in figure 7-1, they are as follows:

![]() Business model innovations: These included new revenue models, pricing schemes, and channels to market. LEGO split this into two subcategories: the Sales Channel and Business Model. For The LEGO Movie, LEGO generated income by licensing the characters and stories from the movie to producers of clothing, backpacks, alarm clocks, and other types of branded merchandise. This was not a risky or difficult creative challenge for LEGO, and it generates a significant amount of revenue if done well. LEGO might have also explored innovations in the other category, the Sales Channel—for example, by selling LEGO toys in the lobbies of movie theaters. If it had done that, it would have appeared in the far left column of the matrix.

Business model innovations: These included new revenue models, pricing schemes, and channels to market. LEGO split this into two subcategories: the Sales Channel and Business Model. For The LEGO Movie, LEGO generated income by licensing the characters and stories from the movie to producers of clothing, backpacks, alarm clocks, and other types of branded merchandise. This was not a risky or difficult creative challenge for LEGO, and it generates a significant amount of revenue if done well. LEGO might have also explored innovations in the other category, the Sales Channel—for example, by selling LEGO toys in the lobbies of movie theaters. If it had done that, it would have appeared in the far left column of the matrix.

![]() Product or service innovations: This category is split into the key product and the complementary products and services around it. In the case of The LEGO Movie, the film itself represented a major challenge and opportunity. While making movies was by no means core for LEGO, the movie would have been the key product for the team managing the movie, and the LEGO kits would have been complementary products. The team would also have worked with outside partners to develop other complementary products, such as PC games and books.

Product or service innovations: This category is split into the key product and the complementary products and services around it. In the case of The LEGO Movie, the film itself represented a major challenge and opportunity. While making movies was by no means core for LEGO, the movie would have been the key product for the team managing the movie, and the LEGO kits would have been complementary products. The team would also have worked with outside partners to develop other complementary products, such as PC games and books.

![]() Customer innovations: This group can include marketing innovations, customer experience innovations, and the development of customer communities. LEGO invested a great deal into supporting its communities of adult and adolescent fans, so it separated community development activities from more traditional marketing activities. One marketing innovation that the company’s movie team invested in was an agreement with the Ellen DeGeneres Show to send its writer Adam Yenser to a LEGO store to play pranks on customers.7 The segment appeared just before the launch of the movie. To involve its fan community in the development of the movie, LEGO created a contest on its Rebrick fan site, where it challenged fans to create their own animated LEGO movies.8 Brief clips from the best entries appeared in The LEGO Movie.9 The contest was a low-cost way to generate fan interest and enthusiasm for the movie.

Customer innovations: This group can include marketing innovations, customer experience innovations, and the development of customer communities. LEGO invested a great deal into supporting its communities of adult and adolescent fans, so it separated community development activities from more traditional marketing activities. One marketing innovation that the company’s movie team invested in was an agreement with the Ellen DeGeneres Show to send its writer Adam Yenser to a LEGO store to play pranks on customers.7 The segment appeared just before the launch of the movie. To involve its fan community in the development of the movie, LEGO created a contest on its Rebrick fan site, where it challenged fans to create their own animated LEGO movies.8 Brief clips from the best entries appeared in The LEGO Movie.9 The contest was a low-cost way to generate fan interest and enthusiasm for the movie.

![]() Process innovations: These innovations are often split into categories, depending on whether they’re part of the product manufacturing and distribution chain or part of other supporting processes. For LEGO, participation with an outside creative team would have represented a significant challenge to the product development process. Ensuring that the story and characters were compelling and appropriate was a high priority for the company, and working with an outside team from Hollywood was a risky, unfamiliar challenge.

Process innovations: These innovations are often split into categories, depending on whether they’re part of the product manufacturing and distribution chain or part of other supporting processes. For LEGO, participation with an outside creative team would have represented a significant challenge to the product development process. Ensuring that the story and characters were compelling and appropriate was a high priority for the company, and working with an outside team from Hollywood was a risky, unfamiliar challenge.

These different innovation categories—the columns in the matrix—will usually correspond to different functional groups inside the organization. Where each specific innovation should be categorized will depend on the organizational group responsible. A comic book might be managed by the core project team if it is to be tightly connected to the stories in the movie, while a coloring book that only contains images from the movie might be managed by the LEGO licensing group.

The vertical axis reflects the riskiness of each innovation. In the previous chapter, we discussed how the riskiness of a complementary innovation should be assessed according to its effect on the key product. That assessment can now be used to determine where on the vertical axis an innovation falls. The lowest level of risk denotes an innovation that requires little integration with the key product and is less important to delivery of the promise. High-risk innovations—those that need a great deal of integration and are very important to delivery of the promise—will occupy much of management’s time and attention. For The LEGO Movie, the dozen or so kits that were in stores when the movie opened represented a medium level of risk, not because they were difficult for the company to produce but because their success was critical to the overall promise of the movie—to create a compelling story that kids could play out with real LEGO bricks.

To use the innovation matrix for managing the Third Way, start by locating in the matrix the key product you’ve chosen, based on the innovation category (horizontal axis) and the risk level (vertical axis) where it belongs. Then, in decisions 2 and 3, as you identify possible complementary innovations, place each innovation in the appropriate spot in the matrix.

Once you’ve filled it in, the innovation matrix serves four overall purposes:

![]() To help the solution integrator communicate to the organization which innovations the team is pursuing.

To help the solution integrator communicate to the organization which innovations the team is pursuing.

![]() To provide guidance on which parts of the organization need to be involved.

To provide guidance on which parts of the organization need to be involved.

![]() To support the management committee as it tracks and monitors the ongoing execution of the project.

To support the management committee as it tracks and monitors the ongoing execution of the project.

![]() To raise important questions. Does the team have the skills it needs to manage each of these innovations? With whom will the company partner if it doesn’t have the skills? What is the overall risk level of the project?

To raise important questions. Does the team have the skills it needs to manage each of these innovations? With whom will the company partner if it doesn’t have the skills? What is the overall risk level of the project?

In short, the matrix is a concise way for the solution integrator to communicate the scope and challenge of the project to everyone involved. And it’s an excellent tool to help assess whether the project team has the right skills and experience.

A Third Way Business Plan: Local Investments and Global Profits

Any corporate effort that crosses organizational boundaries will inevitably raise thorny questions of income and expense. These issues are difficult to resolve with outside partners, but can become even more difficult when they cross lines within an organization. For example, transfer-pricing disputes between divisions can be some of the most contentious issues in any company. The success of the effort will depend on explicitly raising and answering these types of questions as quickly as possible.

The first step in finding answers is for you and your team to combine all your Third Way efforts around a key product into a single business plan that includes all those efforts, identifies the roles played by each, and shows how those elements combine to produce an overall profit. The need for an overall profit does not mean every complementary innovation must show a profit. Some innovations, such as new ways of marketing and advertising the product, will be natural expense items that no one expects will directly generate revenue. In that kind of situation, the sticky issue will be deciding whose budget must absorb the expense.

Even trickier discussions can occur around innovations that do

produce revenue. For those, the Third Way team will need to decide whether it makes sense to turn a profit on that income. It’s an important question because creating a profit for the system overall may mean—for the good of the whole portfolio—that some complementary innovations will not be profitable. Then the question becomes, who will absorb the loss?

Consider just three negotiations that the matrix might have sparked between LEGO and the movie team at Warner Brothers when the two groups were cooperating on The LEGO Movie.

![]() How much should LEGO invest in the movie? For The LEGO Movie, the author’s analysis of The LEGO Group’s financial returns in 2014 indicates that the company neither invested much in the movie nor shared much in the movie’s profits. The LEGO business model was, and still is, to sell boxes of plastic bricks, and the company was quite successful in selling the toys associated with the movie. But its decision meant that LEGO missed out on the windfall profits produced by the unexpectedly large success of the movie in theaters and after.

How much should LEGO invest in the movie? For The LEGO Movie, the author’s analysis of The LEGO Group’s financial returns in 2014 indicates that the company neither invested much in the movie nor shared much in the movie’s profits. The LEGO business model was, and still is, to sell boxes of plastic bricks, and the company was quite successful in selling the toys associated with the movie. But its decision meant that LEGO missed out on the windfall profits produced by the unexpectedly large success of the movie in theaters and after.

![]() Who pays for marketing? There was a very expensive promotional campaign around the movie. But this promotion benefited both the movie and the brick sets that accompanied the movie. Who should pay for that promotion? Our sources tell us that Warner Brothers paid this cost, a standard arrangement for partnerships like this.

Who pays for marketing? There was a very expensive promotional campaign around the movie. But this promotion benefited both the movie and the brick sets that accompanied the movie. Who should pay for that promotion? Our sources tell us that Warner Brothers paid this cost, a standard arrangement for partnerships like this.

![]() Who gets the licensing revenue? The LEGO Movie project spun off more than LEGO toys. Many other types of branded merchandise were available, each of which returned a share of the revenue to the company that owned the rights to the characters. In the case of The LEGO Movie, we believe that the LEGO Group received most of that income.10

Who gets the licensing revenue? The LEGO Movie project spun off more than LEGO toys. Many other types of branded merchandise were available, each of which returned a share of the revenue to the company that owned the rights to the characters. In the case of The LEGO Movie, we believe that the LEGO Group received most of that income.10

As you construct the business case for your portfolio of innovations, you will inevitably come across challenges like these. If you address them early, as partnerships are being formed, they can be addressed amicably and easily, leaving enough profit for all parties.

The key for constructing your business case is to set local investment budgets and global profit targets. Investments should be managed very carefully for each individual complementary innovation, but profits must be considered as a whole so that the overall benefit to the company can be optimized. This dual approach may sound simple and obvious, but it can be difficult to achieve. Companies often have rigid cost accounting systems that require tightly defined business cases. The result can be a divergence of objectives, resulting in subteams that strive to optimize their individual profit pictures at the expense of the whole.

For example, suppose the outside team producing The LEGO Movie and the toy development team inside LEGO were operating under separate business plans, each separately striving to maximize its profit and minimize investment. Each would have different views about when the movie should open. Although it was produced to appeal to all ages, the movie was primarily created for the core LEGO demographic of five- to nine-year-old kids. Movies like that are traditionally brought out either over the end-of-year holidays or during the summer months to maximize their revenues. But the team producing LEGO toys didn’t want the movie to come out near the Christmas holidays. The company didn’t need to boost sales of bricks sets during that period, when the challenge was more often keeping shelves stocked. If the business plans had been done separately, the movie team would have released the movie near Christmas time, a move that would have ultimately led to lower sales of the associated toy sets. But the LEGO team had anticipated this issue and retained overall control of the release date. After some difficult discussions between the teams, The LEGO Movie came out in February 2014. The LEGO team chose that date because it was quite happy to sacrifice movie revenues to maximize revenues from the toys.11 This was obviously a difficult discussion with Warner Brothers, but one that LEGO had prepared for from the beginning.

The need for strong and clear management here can’t be overestimated. If you’re not clear about who or what will or won’t make money and how different cost and revenue streams will be allocated, the whole interdependent system you’re trying to assemble can fall apart. If every group acts independently to drive hard bargains with outside partners, the result may be an overall reduction in the profits from the portfolio as a whole.

Leading a Third Way Project

Decision 4 is not one discrete decision, but a set of related decisions that begin right at the start of a Third Way project. We separate them into their own category because they’re uniquely different. They’re concerned with how the project will get done rather than what the team will produce. One of the first of these smaller decisions will be to fill the solution integrator role and give that person the scope of authority he or she needs, as described above. The solution integrator will then begin to build the project team. One critical member will be the product manager, the person who leads development of the next version of the key product. While this person should no longer be the overall project leader with P&L responsibility or final say over product specifications, there still is a need for someone to serve as guardian of the key product.

As the project moves forward into decision 2 (define the business promise), the team will begin the process of understanding both the customer and the context in which the customer uses the key product. To support this step, the team will need to add members who have the experience and skills needed to do in-depth field research and uncover latent needs. Ensuring that this information is captured, documented, and communicated is an important part of the solution integrator’s role.

When the project moves to decision 3, choosing specific complementary innovations, the team must expand to include the people who will create and manage the complementary innovations that the team ultimately chooses. As the project team evaluates possible complementary innovations, it may discover that some are in categories that have no representation on the team. New team members will need to be identified from different parts of the company or from outside consulting firms. The goal will be to build a team that has the capabilities needed to select, design, and integrate a complete set of complementary products, services, and business models around the key product. The innovation matrix will help the solution integrator communicate the need for those partners to management.

After choosing complementary innovations in decision 3, the team must then choose who will be responsible for developing each. The key factor in this choice is risk. For whom will creating the innovation be less risky? Using an outside group that has experience in successfully producing the types of innovation you’re now considering will usually be less risky than giving the task to an inside group with no relevant experience. But factors other than experience—the complexity of integrating work done outside, for example—also matter because there are risks other than financial. When Guinness chose an outside company to pursue the pub concept, the brewer had to work closely with that firm to make sure the inclusion of Guinness product—how it’s stored, served, and represented (in wood carvings, for example), was done well.

As we mentioned above, if you can define the leadership role well, specify the project scope properly, and build a global business case, then the project planning should be fairly straightforward. But that doesn’t mean it will be easy or familiar. For example, when LEGO worked with Warner Brothers on the timing of The LEGO Movie, it quickly learned that the movie would take many years longer to develop than the brick sets. While LEGO was very familiar with the challenge of tying its toys to movie themes, such as Star Wars and Harry Potter, the company found itself in the unfamiliar role of helping to create the characters and storylines in the movie from the beginning. The result was a project that was much longer, riskier, and ultimately more rewarding than a traditional LEGO play theme.

Senior Management’s Role in Third Way Projects

Senior management has a key role to play in Third Way success. Too often, corporate leaders say the right words about the need for an expanded project management role, but then they put product managers in the same old box of expectations and constraints. That is, they still reward them for the quality of their products, rather than their ability to mobilize the entire organization to create a complete portfolio of complementary innovations. If they want something new and different from people hired and trained to develop products, corporate leaders need to hire differently, train differently, reward differently, and set different constraints, targets, and metrics.

Probably the most important task for top management is to set up the Third Way team for success. The key is to set the right expectations for the head of the team, the solution integrator. They should make clear what they expect from this person and the team:

![]() They should expect not just a great product but a complete customer solution created by selecting, designing, and integrating a coherent system of products, services, and business models around a key product.

They should expect not just a great product but a complete customer solution created by selecting, designing, and integrating a coherent system of products, services, and business models around a key product.

![]() They should expect to see a profitable portfolio, not necessarily a profitable product.

They should expect to see a profitable portfolio, not necessarily a profitable product.

![]() They should expect the solution integrator to lead a complex cross-company effort, not just a small internal team of R&D personnel.

They should expect the solution integrator to lead a complex cross-company effort, not just a small internal team of R&D personnel.

![]() They should expect decisions to be made based on market data and experimentation, not the opinions and hunches of managers, including themselves.

They should expect decisions to be made based on market data and experimentation, not the opinions and hunches of managers, including themselves.

After setting these new expectations, senior managers must then actively support the solution integrator as he or she works across the organization and inevitably calls on functions to accept such unappealing outcomes as forgone revenue and higher expenses and to provide the project with skilled people whose functional bosses would have preferred to use them elsewhere.

One Final Piece of Advice

The Third Way is a different approach to innovation. The overall purpose of this book has been to convince you that it’s an alternative every company should consider. And the purpose of this chapter has been to help you understand how to adapt your internal processes, roles, metrics, and structure so that, if you do try the Third Way, your teams will have a reasonable chance of success.

Our final piece of advice is simple: start small and start local.

A company pursuing the Third Way for the first time is more likely to succeed if it begins with a reasonably sized effort that it treats as a one-off project. It’s important for leaders to be clear about what’s being done and what this approach requires of people and managers. But mistakes, false starts, and dead ends are virtually inevitable, and so it’s usually better not to begin by announcing a big new initiative and making permanent structural changes right away.

There’s a significant corporate learning curve that must be ascended. So pursue the Third Way at first as a single project, and focus on doing it well. Give people temporary roles and assignments. Set up ad hoc teams and committees. Then, after gaining experience and getting the process to work reasonably well, institutionalize the approach. The advantage is that when you do make permanent structural changes—new positions, different roles, new teams, new assignments—people will understand what’s happening and the chances of longer-term success will rise significantly.

Three Takeaways for Chapter 7

![]() The Third Way, a new and different approach, calls for a new kind of leader to manage a new process. Putting a product manager with a narrowly defined set of responsibilities in charge will doom a Third Way project. The leader must be a solution integrator who possesses the skills and authority needed to work across the organization with people and groups from multiple functions.

The Third Way, a new and different approach, calls for a new kind of leader to manage a new process. Putting a product manager with a narrowly defined set of responsibilities in charge will doom a Third Way project. The leader must be a solution integrator who possesses the skills and authority needed to work across the organization with people and groups from multiple functions.

![]() One of the first tasks of the solution integrator should be to construct an innovation matrix that shows all the different complementary innovations needed to deliver on the business promise.

One of the first tasks of the solution integrator should be to construct an innovation matrix that shows all the different complementary innovations needed to deliver on the business promise.

![]() Just as the solution integrator role should have responsibility for the entire project, the business plan should cover all phases of the project. While the different parts of the project will have tightly defined and carefully managed investment targets, the profits should be shared and maximized across the entire project.

Just as the solution integrator role should have responsibility for the entire project, the business plan should cover all phases of the project. While the different parts of the project will have tightly defined and carefully managed investment targets, the profits should be shared and maximized across the entire project.