1. An Organization at a Crossroads

Organizations riding high on waves of success don’t feel the need to change. All too often, they remain comfortably complacent even as their positions slowly erode. Only when their existing management approaches and business models are imminently threatened do they start to feel that, perhaps, they should try something different. By then, it can be too late.

Even foresighted leaders who see the challenges ahead may have trouble motivating their organizations to change. People get comfortable with their existing way of working, and while they welcome incremental improvements to the status quo, motivating sweeping change is all but impossible. And agile change, by its very nature, is sweeping, disruptive change.

Leaders who want to help their organizations adapt to increasing competition and uncertainties need to find pockets in their organization that need to work in a different way to succeed, and then help these parts of their organization find their own way of working. No leader will be able to overcome the inertia of the larger organization’s complacency overnight, but by focusing on smaller pockets of innovation, such a leader can slowly start to shift the balance in favor of the necessary broader changes.

Complex Challenges Create Urgency for Agility

Doreen is the CEO for a traditional electrical utility, Reliable Energy, with a history going back more than 100 years. Its current business model is based on supplying energy from its own generation facilities over its own grid, which is in turn connected to regional and national grids that allow the firm to sell and buy power from other similar companies. This business model is being challenged by new independent distributed generation technologies like wind, solar, and other technologies that provide energy more cheaply and more sustainably. Reliable Energy has begun to accept that its government-granted monopoly will eventually be withdrawn, and it needs to develop new products and services, and new business models, if it is to survive and thrive in the future.

Leaders are formed in crucibles of extreme change for which one is never fully prepared. There are no warm-up act, no safety net, and no second chances. There are also no experts to consult, no “best practices” to adopt. These crises are rough-and-tumble, hands-on, hold-on-to-your-hat rides that demand the best of people, and in return, help to develop people in ways that they could not have imagined.

Leaders are formed in crucibles of extreme change for which one is never fully prepared.

Leaders are essential catalysts who help their organizations adapt to changing conditions. Leading change, especially during existential crises, is their fundamental purpose; it is what separates leadership from management. Management deals with maintaining and improving an existing, working organization. Leadership, in contrast, deals with creating a new organization, and a new culture, sometimes from nothing, but often from the wreckage of an earlier organization that was no longer capable of meeting new challenges. Leadership is, fundamentally, about confronting the unknown and growing the organization’s ability to deal with it.

Change can be intimidating, even paralyzing. Dealing with the unknown is never easy, but ignoring it never makes it go away. The only way to move ahead is to plunge right in, keep your eyes open, ask a lot of questions, and be prepared to try different approaches, examine the results, and adapt based on the new information. The case study explores how a large, traditional organization learns how to pivot by changing its culture and the company’s explicit and implicit reward system to embrace empiricism and transparency.

Reducing Dependencies Makes Change Possible

Dependencies are the enemies of change. Many organizations are so internally intertwined that they can’t change even small things without breaking lots of other things. They try to manage complexity with more planning, which does expose the dependencies, but changing within the constraints imposed by these dependencies requires such execution finesse that the pace of change slows to a crawl.

Dependencies are the enemies of change.

The best way to manage dependencies is to eliminate them. One way to do so is to implement stable, defined interfaces between products or different parts of the organization. Doing so enables different parts of the organization to change the way they work without disrupting others. It also helps organizations create partner ecosystems by providing ways to build value-added products and services on top of existing products. As a result, interfaces have become an integral part of most new-product strategies. Coordinating activities and dependencies across products slow everyone down to the speed of the slowest team. Interfaces sever these dependencies and let different teams move at the pace that best matches their needs and abilities.

Organizations can reduce complexity in several ways. Using shared architectures or platforms, as the teams in the case study propose to do, is one way to achieve this. Another way is to simplify the products themselves. Most products are complex collections of features that serve many different groups of people. By using a shared product architecture and breaking complex products into simpler products that serve a smaller, more cohesive group of people, organizations can reduce the dependencies between products so that instead of depending on many other products, each product depends only on the shared product platform.1

1. For more about this approach, see www.pragmaticinstitute.com/resources/articles/product/untangling-products-focus-on-desired-outcomes-to-decrease-product-complexity/.

Not Everyone May Need to Change, at Least at First

While the entire organization needs to develop a new business model, it can’t simply pivot to the new model immediately; it has existing customers and suppliers that depend on the old business model, at least at the present time. Forcing the entire organization to change and potentially damaging the existing model is as dangerous as failing to develop a new business model to replace the one that will inevitably fade. Being mindful of who needs to change, and why, is the starting point for the discussion on how to change, and when. People struggle to adapt when they aren’t sure why they need to be agile.

Many organizations state that their reason for wanting to improve their agility and responsiveness is to “go faster” or “deliver faster,” but this doesn’t really tell the whole story. Those organizations that measure the value that they deliver to their customers by gathering feedback often find that they have a lot of misconceptions about what customers really need. Sometimes, they find that customers also don’t understand what they need.

At first, these organizations may be shocked, because they thought that their stakeholders had a deep understanding of customers’ needs. Once they overcome this shock, they can see that a lot of what they had planned to deliver isn’t useful—and this knowledge frees them to pursue things from which customers will derive more benefit.

When dealing with a world that is changing rapidly, the only way to learn what is really needed is often to try things and see if they will work. The art of doing this is to experiment quickly, and with the smallest investment needed to learn. Traditional organizations make too many expensive assumptions and then take too long to test them. They think they have to have all the answers, and change everything at once.

In a complex world, organizations usually don’t know what needs to change. Because they need to learn by taking many small, quick steps, not everyone needs to change all at once. But who does need to change? That answer is simple: the people who are going to run the controlled learning experiments.

As the organization learns, more and more teams will find over time that they need to more directly engage with customers to test assumptions and learn more about what customers need. But the learning will be slow at first, and will involve a small number of teams, because at first the organization won’t even know which questions to ask or how to frame experiments. Each team needs time to form and to learn a new way of working. In short, they need to learn how to learn. Before teams can improve their time to deliver, they first have to focus on decreasing their time to learn.

Not Everyone Sees Complexity the Same Way

Carl’s experiences color his perceptions. He believes that with enough up-front information, plans for solving problems and delivering solutions can be developed and executed. His beliefs about the “right way to manage” shape his approach to planning: Problems are understood, an approach is defined, the right practices are selected, a plan is created, and then the organization’s execution of that plan is monitored. Carl’s approach assumes that the plan is right, and deviations from the plan are indications that corrective action is required.

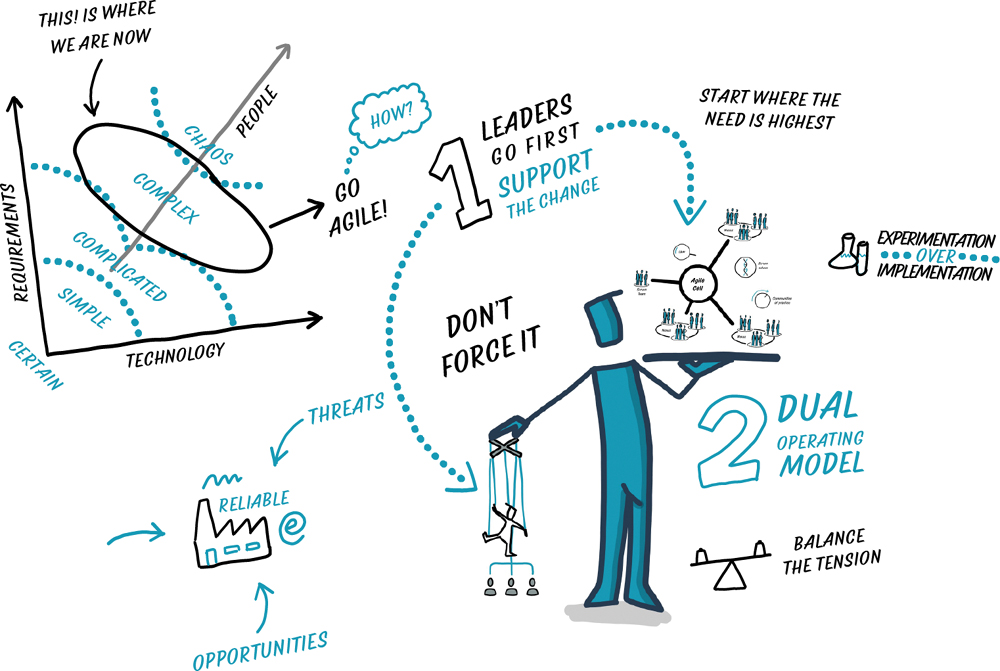

Some people believe that many of the same benefits that agility promises—namely, delivering faster with less waste—can be achieved by better planning, and that plans are essential to coordinating the activity of large numbers of people. And when requirements and assumptions are correct and stable, Carl’s approach is perfectly reasonable. But when everything is in flux, the plan-centric approach falls apart. Many of the most challenging problems that organizations face today are novel and complex, and this novelty defies attempts to use our experiences of cause and effect to create plans that lead to effective solutions.2

2. Inspired by Dave Snowden, “The Cynefin framework”: www.cognitive-edge.com/the-cynefin-framework/.

When everything is in flux, the plan-centric approach falls apart.

Changing someone’s view of the world is difficult, if not impossible, at least from the outside. People must experience the world in a different way to change the way they look at it. They have formed their belief system based on their experience, and it takes a lot of countervailing evidence to change it. Arguing with them that their approach isn’t working usually causes them to dig in and double-down on their position.

Organizational Change Requires Protective, Progressive Dictatorship

The irony of agile organizational transformation is that while eventually the people in the organization will need to learn to become more self-managing and collaborative when they make decisions, the early stages of the change require the agile leader to be somewhat dictatorial. That person needs to create a space in which people can experiment and learn, even while some other parts of the organization are trying to shut down the change.

Different terms have been used to describe the “protected environments” in which new approaches can be tried without interference from the rest of the organization: skunk works, innovation labs, incubators, and the like.3 The key enabler of these environments is a progressive, politically powerful executive who charters the organization to achieve a mission, provides the organization with the resources that it needs to survive, and, most importantly, protects the group from outside tampering.

3. For an example, see this description of the Scrum Studio: www.scrum.org/resources/scrum-studio-model-innovation.

The “incubator” or “innovation center” metaphor that is usually applied to these groups is actually misguided when trying to use them as mechanisms to change the organization. On the one hand, incubators usually produce a prototype, which then needs to be transitioned into some steady-state existing organization. Calling this group an incubator suggests that what it’s doing is not really “ready for the real world”—and that’s not the case with agile change.

On the other hand, while promoting innovation is a good thing, the term “innovation center” can result in a belief that innovation has to happen in some special group to be legitimate. In reality, opportunities for innovation arise everywhere in most organizations.

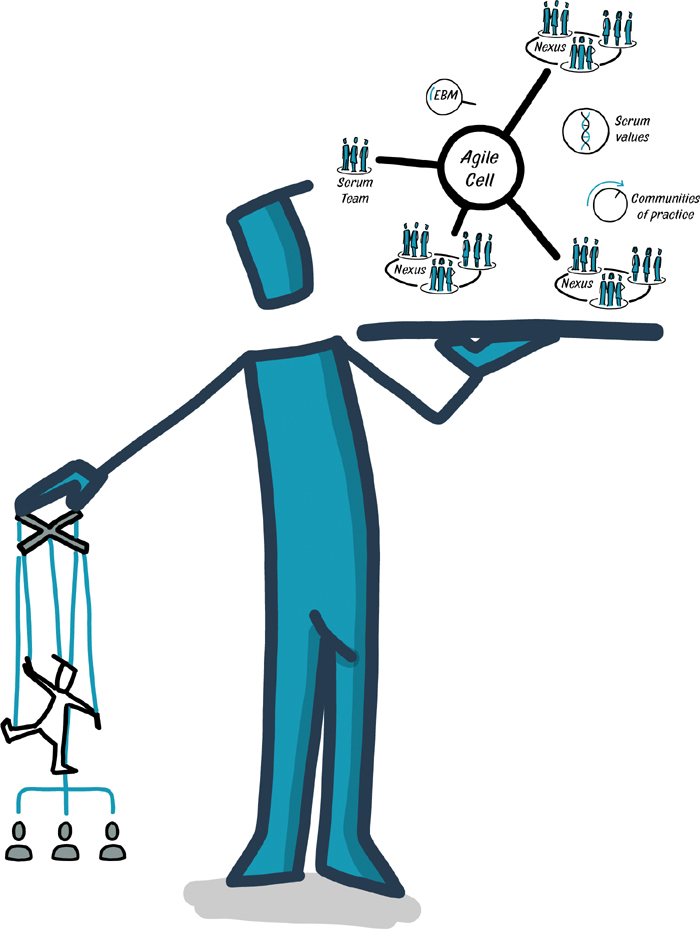

In the case of agile transformation, what really should happen is that the so-called innovation center is actually exploring and refining a new way of working that will eventually need to be replicated in other areas of the organization. For this reason, the term “agile cell” best describes how these early agile teams should be regarded—as cells that ultimately need to reproduce and spread through the organization. But more about this later.

Two Paths, One Goal

Existing organizations face a challenge that start-ups don’t: They need to support the current business, even if they realize that their current business may be going away and they need to develop a new business model.4 In response, creating dual, parallel organizations is one way that they try to do both.

4. Inspired by John Kotter’s discussion of how traditional organizational hierarchies evolve: www.kotterinc.com/book/accelerate/.

The key challenge for the agile leader is to make it permissible to work in different ways so long as everyone is working toward the same goal. Minimizing dependencies, as noted earlier in this chapter, is one way to minimize the conflicts and complexities of coordinating work being done by teams working in different ways (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Supporting two different operating models helps organizations to balance agile and traditional approaches.

Every existing organization faces a challenge when evolving a radically new way of working: keeping the existing organization focused on serving its existing customers and sustaining the revenues on which it depends. People in the old/traditional part of the organization need to focus on keeping the train running while the organization experiments with new approaches in new areas, or in old areas that have already been disrupted.

The challenge for leaders is that the very act of trying new approaches, even in isolated parts of the organization, is threatening to people in the old organization when it creates fear in them of losing their jobs, their influence, or their status in the long term. Even when they recognize that the organization needs to change, they may resist that change on a personal level because it might cause them to lose something important to them.

The challenge for agile leaders is to understand and respect the perceived threats to the traditional parts of their organizations while creating space in which new approaches can be tried out and refined based on experience. Balancing these two competing forces, and actually aligning them so that both work toward the same goal, is an art that takes practice to master. Exploring approaches that help agile leaders to develop these skills is a major focus of subsequent chapters.

Reflections on the Journey

Organizations seek agility as a way to overcome the challenges they face. When dealing with complex problems, where there are no sure answers and the proven methods of the past are failing, the only successful approach is to take small steps toward goals, measure the results, and then adapt based on what the organization learns.

This doesn’t mean trying to change the whole organization at once. Instead, the organization can choose the area in which it faces the greatest challenge and start there, learning as it goes. This requires a subtle balancing act—keeping the existing organization moving forward while actively trying new approaches that are deliberately trying to find new ways of working. Ultimately, the organization will have to choose which way it goes, but at the start it simply needs to create an environment in which it can try new things and learn.