7. Aligning the Organization

As organizations grow their agility, team by team, product by product, they come to a point where they must either fully commit to continuing their agile journey or they will fall back to the old ways of working. Organizations can continue for a long time with two different operating models, one agile and one traditional, coexisting side-by-side. But they cannot maintain these two models forever; they are incompatible and diametrically opposed. They create and demand opposing cultures. Eventually, one culture or the other will win out.

The “dual operating system” approach1 is a false dichotomy; there is no part of the organization that will not benefit from self-managing teams. The challenge is in helping teams that are just getting started with self-management to learn and grow.

1. https://hbr.org/2012/11/accelerate.

In our consulting work, we have met with many executives who told us that their organizations had tried to become agile, but “it didn’t work for them.” When we visited these organizations, we witnessed very little evidence that they had even attempted to adopt an agile approach; they seemed as trapped by tradition as organizations that had never even attempted agility.

What these executives really meant when they said “agile didn’t work for them” is that their organizations were unwilling to confront the hard realities of agile change: There are winners and losers in the shift to agility, and failing to acknowledge this makes change harder.

Previous chapters have touched on aspects of this issue, because it comes up at predictable points along an organization’s agile journey. This chapter returns to this topic, with greater focus. As an organization proves the value of agility to itself, and as it grows its agile capabilities, there will come a point when it has to choose. This chapter is about making that choice.

For leaders, the essence of this transformation is to eliminate combative and compliant leadership styles, while helping people with competitive leadership style to develop a catalytic leadership style. So long as the leaders in the organization cling to combative, compliant, or competitive leadership styles, the organization will never fully achieve its agile potential.

Evolving the Operating Model

Be Direct and Clear About the Change

The change described in Chapter 5 takes a long time to work its way through the organization. Eventually, the old organization has to be largely dismantled—but if it’s dismantled before agile teams can really take on the work, the organization will fail. There are a lot of moving parts to manage, and the work is delicate (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Over time, agile organizations must trim their hierarchy by transferring responsibility and authority to self-managing teams.2

2. Adapted from www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/the-organization-of-the-future-a-new-model-for-a-faster-moving-world/.

The essence of the process is conceptually simple:

The organization helps a team to form that can own some complex product or service that delivers one or more outcomes to some group of customers. If this product or service already exists, the mission for that product or service transfers to the new team.

The organization supports this team with specialist coaches who provide the team with skills the team lacks, when the team needs the help. Over time, these specialists should help team members to acquire the skills so that they no longer need outside help.

As work is transferred to agile teams, the traditional organization needs to shrink. What is left, in the end, tends to be executive functions and coaches focused on organization direction and organizational development.

At first, outside specialists supporting agile teams can report into a traditional organization hierarchy. In fact, early in the transition, the organization may actually need more specialists to keep agile teams from waiting for help. As agile teams become more self-sufficient, however, the organization will typically not need as many people with specialized skills. In turn, the organization typically will not need as many managers for specialized skill silos.

Once an organization has decided to commit to working in an agile way, it must make it clear that the agile teams are at the center of how the organization works and how customer value is created, and that everything else must be in service to those teams. Specialized skill areas that can’t be absorbed into cross-functional teams can be converted into coaching/knowledge transfer centers, but the organization must always be looking for ways to help teams to be more self-sufficient.

Examples of skill areas and supporting teams that may still need to exist even after agile teams have become “mainstream” include employment law compliance, security (both physical and cyber), other forms of compliance, contracting, litigation, and compensation, among others. The sorts of skill areas that may need specialized support are those that agile teams need infrequently and that require (sometimes licensed) knowledge that an ordinary team would not invest in obtaining.

Growing Self-Managing Teams Organically

Chapter 2 explored how self-managing teams form by helping interested people to self-organize. The discussion there hinted that there was an upper limit to how large these teams could become, usually somewhere around nine people. The reasons for this limit have to do with the complexity of communication networks within the team, which varies depending on the number of people, their level of trust, and the nature of the work on which they are collaborating (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 The Complexity of Communication Networks Within Teams Limits Their Size

| A small team that has just started to build a valuable proposition. There are just enough people to build a minimum viable product. This team might still be missing a few people with infrequently needed skills, such as marketing, finance, operations, security, and so forth, but they can usually obtain these from other parts of the organization, provided that they don’t have to wait for people with these skills to be available to help. |

| A medium-to large-size team that contains all skills it needs to create valuable outcomes for customers. While this team is fully capable of serving its current customers, it may still find opportunities for growth by delivering outcomes that expand its customer base. |

| If a team grows too large, its internal communication network can become too complex so that the team is no longer capable of being fast and effective. Some team members will likely have better connections with each other, which can lead to the formation of team subcultures and subgroups that harm team cohesion and communication. |

What to Do When Teams Become Too Large

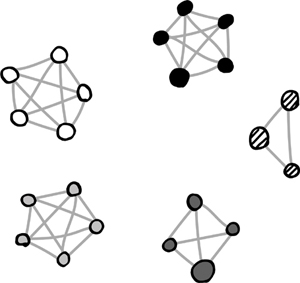

When a team grows too large and starts to lose effectiveness, organizations try a number of strategies to break up the teams (see Table 7.2.)

Table 7.2 Strategies for Splitting Teams When They Become Too Large to Be Effective

| One option to split a team is to organize by components of the overall solution, which are typically assembled by an integration team. For example, for a company like Reliable Energy, these components might each focus on a different functional area of the business. For example:

Other organizations, especially those that do not produce physical products, like financial institutions, often organize by skill area. For example:

The advantage of these structures is that the people on each of these teams do similar kinds of work, which can make it easier to collaborate. The principal disadvantage of these structures is that no one team has any affinity with the customers, and no one team is accountable for delivering value to those customers. Because they need to collaborate with each other to deliver value, they often take a very long time to deliver anything. In addition, because no one is really responsible for value, they typically lack the ability to self-manage to improve their results. This organizational pattern is the foundation for the organizational silos that create many of the problems that traditional organizations experience. |

| A better alternative is splitting a large team into smaller teams aligned with specific customer outcomes, so that each smaller team has all the people and skills it needs to deliver one or more specific outcomes, from idea to actual customer benefit. This model is sometimes called a feature team model, assuming that a feature produces an independent increment of customer value. This way of splitting up a team is especially effective if dependencies on the other teams can be eliminated, so that each team is able to act independently to improve customer outcomes. For example, an energy organization like Reliable Energy might include teams focused on:

|

| When dependencies cannot be fully eliminated, and multiple teams need to collaborate to deliver a specific customer outcome, the teams must expend extra effort to coordinate their activities. This example illustrates a situation where one person (e.g., the Product Owner in Scrum) takes the same role for both teams to help them align on goals and outputs so that the work of each team contributes to achieving a greater goal. In this way, optimal clarity and alignment is guaranteed and communication overhead is reduced to a minimum. |

Scale Agility by Removing Dependencies

Many organizations worry about how to scale agility. They can see how a single team can be agile, but their organizations produce products or services that—at least the way they are organized today—require the efforts of many teams. Because they know of no other way, they envision that scaling agility requires adding oversight and coordination mechanisms to synchronize the work of multiple agile teams.

When these organizations add these oversight and coordination functions, they find that the agility that one self-managing team experiences slowly dies as the oversight and coordination become more intrusive. External oversight and coordination kill self-management. As the responsibilities of each team narrow and fragment, they begin to resemble component teams that don’t deliver outcomes to real customers and cannot really inspect and adapt based on feedback from real customers. And pretty soon, the “scaled” agile organization looks and works just like the old organization that it was supposed to replace.

External oversight and coordination kill self-management.

If you want to scale agility, you have to eliminate dependencies. These dependencies take several forms:

Skill dependencies occur when an agile team does not have all the skills it needs to deliver a valuable, useful product or service increment. This problem is solved by the practices described in Chapter 6, in which people with scarce specialist skills are available whenever an agile team needs them. Over time, these specialists can work as coaches to help agile team members acquire the skills, if the team feels that they need the skills within the team.

Product dependencies arise when a product or service is too large and complex for a single team to deliver. This problem can be solved by breaking the product or service into smaller products or services, each of which provides unique and valuable outcomes for a smaller group of people, and each of which is delivered by a single team. This practice was described briefly in Chapter 2, with a footnote to a supporting article.

Cross-team dependencies exist when the first two kinds of dependencies cannot be completely eliminated. Dealing with these is beyond the scope of this book, but is covered in another book in this series, The Nexus Framework for Scaling Scrum: Continuously Delivering an Integrated Product with Multiple Scrum Teams, published by Addison-Wesley Professional.

Eliminating these dependencies lets agile teams do what they are supposed to do: deliver value incrementally and empirically based on feedback. Bolting on traditional management oversight and coordination practices just complicates the scaling problem.

Consolidating Support and Eliminating Opposition

In every change, some people will benefit and thrive, and others will experience loss of influence. The people with the most to lose are the ones who benefited from the old system. If people in this group cannot find a new purpose in the new organization, they are likely to create impediments to the change. These impediments can range from passive nonsupport to explicit and forceful opposition. Even when the benefits for the organization are clear, don’t expect that people with something to lose will simply accept the change for the greater good.

Expect, Embrace, and Encourage Attrition

As more teams embrace and become effective at self-management, the organization will have less need for traditional managers. Astute managers fear this, and their fears are not unfounded. There are other jobs that the organization needs to have done, but if a person wants to be a traditional manager, they will not find those kinds of opportunities in an agile organization; they will need to seek employment elsewhere.

As more teams embrace and become effective at self-management, the organization will have less need for traditional managers.

Carl’s email is an example of the growing tension in a part of the organization that gradually discovers that the responsibilities of a traditional manager will change. Like Carl, some people will keep opposing the change. They don’t believe in the change, and they’re not going to support it.

In the scenario with Carl, Doreen appears to have made a mistake: She did not see the situation coming, and she did not work proactively with Carl to plan a graceful exit. While his departure is unregretted, it might have been handled better to avoid internal tension and conflict.

Some organizations make the mistake of denigrating people who, for whatever reason, chose to disagree with the path the organization is taking. Sometimes their objections are constructive and addressing them can actually improve the overall solution. Frequently, people who defend the old system were the ones who made it, and the organization of the past, successful. Their criticisms often uncover valid points, and professional respect demands that they are able to give voice to their concerns.

Once their concerns are addressed, however, continued opposition undermines the success of the initiative. In these cases, it’s best to find a respectful way of parting company. Beyond professional courtesy, there is a practical reason: There will always be people remaining in the organization who respect the departing leader, and they will feel better about staying if they feel that people are treated with respect.

Giving audience to dissenting voices is an important part of establishing an environment of trust and transparency. But once issues are resolved, they need to be left behind.

Be Mindful of Leadership Styles, and Act Accordingly

Chapter 5 introduced four different leadership styles: combative, compliant, competitive, and catalytic. The challenge for agile leaders seeking to change their organizations is that they will need to eliminate combative and compliant leadership styles, while helping people with a competitive leadership style to gradually adopt a catalytic leadership style.

As Figure 5.1 suggests, it is very difficult for people with combative and compliant leadership styles to adopt a catalytic leadership style. It’s not impossible, but it takes a lot of effort and willingness to let go of a lot of leadership characteristics that a person might feel are the foundations for their past success. Our past experience suggests that people in these two categories, like Carl, usually decide to leave the organization. If they don’t leave voluntarily, and they won’t change, they need to be helped to move on, up to and including help with outplacement, if they choose to leave the company.

Treating people fairly is one way that agile leaders help to establish a culture of trust and transparency.

People with a competitive style of leadership can evolve their leadership style if they believe that doing so will result in better performance for the organization. What they must let go of is their tendency to view everything as a competition with their peers for status; they must be able to put other people’s growth first if they are to grow themselves. This requires a very significant shift in mindset, and many people take a long time to make the transition. These people usually make their own decisions to “compete” somewhere else.

People who have experience as coaches and mentors usually find developing a catalytic leadership style to be very natural, and they are able to grow their capabilities by building on these past experiences. They also tend to find a natural affinity for experiencing a sense of personal and professional satisfaction in seeing others grow and develop.

But Beware Unwanted Attrition

Change is unsettling, and people react to the stress of change in a variety of ways. When people don’t understand how a change might affect them, they can imagine worst-case scenarios that can cause them to want to leave the stressful situation, even if that means finding other employment. Their response is completely reasonable, even if their fears are unfounded. Leaders need to recognize that change is stressful. They need to listen carefully to what people are saying about the change, and pay even more attention to what people are not saying.

Leaders need to continually communicate why decisions are being made, how they will measure results, and how they will adapt when they need to change course. People in traditional organizations are accustomed to a lack of transparency, and they will typically not fully trust what leaders say until they see their words backed by actions. Careful listening and observation can help leaders detect when they need to improve communication, increase transparency, and put their words into practice.

It has been our experience as consultants that good people leave organizations because they no longer feel they belong. By helping team members see how they fit in, and can even thrive, leaders can help to prevent the departure of the very people they cannot afford to lose.

Sometimes Your Greatest Critic Can Become Your Biggest Ally

Sometimes, a team member will be skeptical of the change and will seem to always find fault with whatever the organization does. Dealing with this sort of person can be one of the greatest challenges the agile leader will face. No one likes criticism, agile leaders included, but they need to resist the temptation to dismiss the criticism as simply troublemaking. Critics can be right, and they may see something that the agile leader does not.

Agile leaders need to develop the habit of listening to all points of view, not just the ones that support their positions. Sometimes people just want to know that they are being heard, and demonstrating openness to diverse viewpoints helps to promote transparency and build trust. Sometimes the critic has a unique perspective that helps everyone to reach a better decision. It also benefits everyone to develop communication skills that help themselves and teams to bring forth and discuss differing viewpoints, backed by data and not just opinion.

Only after critics have had their opportunity to make their case should agile leaders start to consider whether the goal of the criticism is simply disruption. Some people really do thrive on creating conflict, and empowering them is also a mistake. It’s a fine line to walk, and agile leaders need to create open opportunities for discussion without fostering disruption. Constructive criticism is healthy, provided that its aim is to create improvements that can be tested with experiments. But if the will for experimenting is lacking, then the critic’s intent is simply to foment conflict—and leaders will need to move swiftly to stymie it.

Silent Subversion Is Worse Than Open Opposition

The real problem is not the people who openly oppose the change, but rather the people who appear to go along with the change but always find ways to quietly but subtly resist. They may honestly feel that self-managing teams are a bad practice, or simply anarchy. And if the teams are immature and lack appropriate support and coaching, those skeptics would be correct. Unfortunately, their actions and lack of support create the very conditions that they claim to be concerned about.

As a leader, if you have evidence that mature self-managing teams produce results and enable the kind of responsive, creative employee engagement that your organization needs to be successful, you cannot vacillate in your support for agility or you will kill it.

This means one thing: People in a leadership role in your company must be effective supporters of self-managing teams. Those who are not might need help to understand why they need to support the teams to help the organization succeed. If this persuasive effort fails, they won’t have a place in the organization, and they need to go. If they do not reach this conclusion on their own, as Carl has, they need to be helped to this conclusion.

Most people in leadership roles are highly intelligent and, even more so, politically astute. If they understand that their goals and those of the organization no longer align, they will realize they need to move on. It’s best for agile leaders to address this issue in direct terms, out of respect for the person’s past contributions and future career potential, even if that career may be in another organization. They may need time and assistance to find another role. If they have been top contributors to the organization in the past, they have earned this respect.

The worst thing for a person who doesn’t agree with the change is to stay in a place where they no longer want to work. At best, they will be unhappy and unmotivated; at worst, they may sabotage, unwittingly or not, the things the rest of the organization is trying to accomplish. Agile leaders need to actively look for signs that a person truly doesn’t want to be part of the change. In such a case, the person needs to leave, and effective leaders can help these employees move on with their careers in the most effective way possible.

Agile leaders need to actively look for signs that a person truly doesn’t want to be part of the change.

Some project managers, like Carl, view comprehensive planning as the mark of a true professional. People who believe that it’s possible to gather comprehensive requirements or to create comprehensive plans don’t really understand complexity or embrace an empirical approach. Perhaps they don’t perceive that a particular problem is complex, or they do not have enough experience working on complex problems to have experienced the failure of traditional plan-based approaches to solving the problem. If they can’t be brought around to understand and embrace empiricism, they will be a constant source of conflict for the teams on which they work.

Managers are not the only people who may feel that they don’t want to work in a new way. Some traditional product managers liked what they used to do; they like creating comprehensive requirements documents and being the sole point of contact with business stakeholders, and they don’t like being part of a cross-functional team. Meanwhile, some developers and other team members want to work alone and not be part of a team. If these people can’t adapt, they don’t belong on a self-managing team. Agile leaders will have to either find other work for them to do or let them go.

What if Senior Executives Are the Problem?

This problem often arises in organizations in which the move to agility is primarily led by middle management. Middle managers sometimes endure unfair criticism, which suggests that they are the people who most ardently resist change. In most organizations, middle managers are actually the people with the deepest commitment to the organization, the operational knowledge, and the cultural connections; they keep the organization functioning despite a revolving door at the top of the organization.

When senior executives oppose the change, or perhaps more often, are indifferent to or delegate the change, the agile initiative usually fails to gain enough traction to be successful. Without senior executive support, departmental and specialty skill silos remain intact, crippling agile teams with a matrixed management approach that prevents cross-functional teams from forming and self-managing.

Without executive support, real change will not be sustainable.

In these cases, the only solution is for trusted advisors, usually from within the company, to help senior executives come to the conclusion that the organization will fail unless it changes. Once they understand this, their resistance or indifference usually fades and they provide the support the organization needs. Otherwise, they leave, and someone with greater understanding and commitment takes their place.

Realign Compensation Plans

Traditional organizations typically reward individuals for achieving individual results. Sometimes they will recognize team performance, but even then they often single out individuals on teams for special recognition.

An agile organization recognizes that nearly everything that it achieves is the result of a team’s work. Agile leaders need to make a conscious shift away from individual performance rewards and compensation plans, and toward team recognition.

At the same time, individuals compete in the labor market for compensation, and people want to know that their compensation reflects their value in the broader employment market. Different people will have different marketability depending on the value of their skills in the market.

So how do leaders balance the need to reward teams with the need to ensure that individuals feel their compensation reflects their market value? Most organizations are familiar with a base pay plus variable pay compensation system. For an agile organization, the base pay for an employee reflects the market value of their skills, which is influenced by factors such as demonstrated skill proficiency and experience. An employee’s variable pay would then be based on team performance, which usually reflects the value to the organization that the team creates by delivering customer outcomes.

Truly self-managing teams should be able to decide how to divide a variable compensation pool amount between team members, although the ability to do so without contention is the mark of a very high-performing team. Leaders may need to help teams to decide by coaching them, so long as they are not perceived by the team as trying to influence the result.

Leaders and staff in “coaching areas” should be measured by how effectively they support teams, with the greatest emphasis given to how effectively they transfer knowledge to agile teams, and how effectively those teams deliver value to their customers. These people in supporting roles can still work in an agile team, supporting the other teams to create value.3

3. For more information on this topic, see this blog: https://evolutionaryleadership.nl/news/all-teams-need-to-be-agile/.

Realign Career Paths

As mentioned earlier, agile organizations tend to have less hierarchy than traditional organizations. In consequence, agile leaders have fewer opportunities to reward people through promotion to higher levels in the hierarchy. They have to find other ways to provide people with rewarding careers, such as improving their sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Promotions reward people in two ways: They increase a person’s compensation, and they increase a person’s prestige in the organization. Compensation was already discussed in the context of rewarding individual performance, and the same approach works for promotion-related salary increases.

Finding alternatives that increase a person’s prestige without using promotion requires understanding that much of the increase in prestige that comes with a promotion stems from recognizing the promoted person as having valuable experience and expertise that enable them to have influence beyond their own individual concerns. The most logical expression of this understanding in an agile organization is to recognize people for their ability to grow others by coaching and mentoring. Doing so provides the coach/mentor with public recognition that their experiences are both valuable and valued, without the disadvantages of having to create a new position in the organization’s hierarchy.

Embrace Catalytic Leadership

As noted in prior sections, and in Chapter 6, leaders in agile organizations need to adopt a catalytic leadership style by gradually evolving their focus from directing to coaching and mentoring. While many leaders have great intuition about helping others to develop, they may benefit from developing their coaching and mentoring skills by being coached and mentored themselves.

Catalytic leaders’ goal is to help others develop their ability to recognize opportunities to improve both their own skills and those of their team. They then help those people develop ideas about how they could improve, and support them as they try out those improvement ideas. Effective coaches don’t tell others how to improve; they stimulate people to develop their own approaches and improve based on experimentation and feedback.

Catalytic leaders aim to create new leaders.

This means, most importantly, that catalytic leaders are patient. They don’t become frustrated when a person’s or team’s first ideas on how to improve don’t produce the hoped-for results. They help people to examine their results for things that they can learn, and encourage them to adapt their approach based on these insights.

Most leaders are on a journey in this respect, and they need to apply the same patience and introspection to their own learning journey. They will not do everything perfectly at once. They may never be perfect. But as long as they are willing to take the time to make thoughtful attempts to learn and improve based on experience, they will get better over time.

Replace Status Meetings with Transparency

Traditional plan-based status reporting is usually subjective, though sometimes it appears to have a veneer of objectivity when it is based on adherence to schedules, or budgets, or features complete.

As discussed in Chapter 3, everything about a plan-based system is a guess. The features that the organization thinks are needed to achieve the outcomes the organization hopes to produce are a guess, as the budget needed to build those features, and the time that is needed to build those features. Even if a project delivers on time and on budget, it may fail to achieve the hoped-for outcomes.

Traditional status reporting is largely theater. It is the opposite of transparency. Because they are pressured to show positive results, project managers present selective information that casts the work performed, expressed in activities and outputs, in the most positive light possible.

Instead of false reports of progress based on activities and outputs, everyone in the organization needs to understand the goals of the work and the evidence of what the teams have achieved to show progress toward those goals—including, sometimes, evidence that the goals are wrong and need to be reconsidered. The only way to achieve this is to be completely transparent about what the team is working on, and why.

This is a big cultural shift for most organizations. Everyone needs to get comfortable talking about goals and results, rather than activities and outputs. And they need to find ways of sharing this information without creating extra work in the form of status meetings or status reports.

Organizations that are leaving behind traditional approaches also need to become comfortable with partial, incremental results. Sometimes this is a challenge for people: They are used to not having anything useful until the end of a project, at which point they are supposed to get everything. Except they don’t get everything, and what they do get is almost always partially wrong.

Instead of expecting to get everything they want at the end, people in the organization need to get comfortable with seeing partial results at regular intervals. When these partial results are aligned with customer outcomes, progress is easy to understand. This is the essence of the agile approach, but many organizations don’t understand how much the success of an agile approach depends on transparency.

Transparency can be threatening, however. Stakeholders frequently find out that their understanding of customers’ needs was off, and that the “killer feature” that they fought for so fiercely hasn’t been used at all by customers. But they can also discover that customers find something else even more valuable than they had understood before, and that knowledge leads to better outcomes for everyone.

Transparency will, at some point, make everyone “look bad.” None of us knows as much as we think we do, and if you’re going to follow an agile, empirical approach you’ll need to accept that you’re going to be wrong some of the time. Finding out that you’re wrong creates opportunities to learn, but only if your organization’s culture is open to that learning.

In fact, when organizations first try to do something new, including embracing agility, they are almost always wrong, because that’s when they know the least. Agile leaders must recognize and accept this truth if they are to provide the space and freedom to stimulate teams to learn and improve.

To illustrate this, Ed Catmull describes the way that Pixar turns early “bad” ideas into great movies:

“Early on, all of our movies suck. That’s a blunt assessment, I know, but I choose that phrasing because saying it in a softer way fails to convey how bad the first versions really are. Pixar films are not good at first, and our job is to make them so—to go, as I say, ‘from suck to not-suck.’ Candor is the key to collaborating effectively. Lack of candor leads to dysfunctional environments.”4

4. Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace, Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration.

Pixar’s “brain trust” process helps establish candor as desirable in this organization. Agile approaches use similar practices like reviews and retrospectives to help teams create the transparency they need to quickly expose bad ideas so that they can improve them into good, or even great, ones.

Agile leaders need to create the space in which teams can learn. They have to demonstrate that everything we think we know could be wrong, and that it’s better to find things out as early as possible. And they have to reward teams for being completely transparent.

Be Realistic About How Long the Transition Will Take, and What It Means

Descriptions in books like this can sometimes leave the reader with the impression that these transitions are easy, or they will occur quickly. Most organizations actually take many years to reach the point where they can start realigning the organization, and the realignment, in turn, takes many years.

Executives expecting quick results need to reset their expectations. Then again, executives expecting quick results rarely have the patience or the dedication to see through a change like this. They may start the change, but as soon as they can claim some small victory, they will be off to seek some other promotion. Agile change is for the far-sighted and for those willing to put aside their own personal benefit for the betterment of the larger organization.

In fact, self-serving “leaders” don’t do well in agile transformations because they cannot see beyond their own self-interest. It’s usually the self-serving “leaders” who need to exit the organization for self-managing teams to thrive and for the organization to reap the full benefits of agility. The leaders who thrive in the transition will be those who gain a great sense of satisfaction in helping other people to develop their abilities and to thrive.

Reflections on the Journey

Early in this book, the authors advocated for a dual operating system model, in which the nascent agile organization coexists alongside the traditional organization. This is important as the agile organization forms and grows. However, as the new organization grows and matures, the traditional and agile organizations often find themselves in fundamental conflicts on their values and basic ways of working. For example, an organization cannot, in the end, have two different ways of rewarding people: one based on individual accomplishment as determined by management, and the other based on team achievements and team member contributions based on 360-degree feedback.

Eventually, if the agile organization is successful in achieving its goals, it will have earned the right to take on more responsibilities. Agile leadership plays a critical role in gradually transferring more and more responsibilities from the traditional organization to the agile organization. This transfer does not happen all at once, but happens gradually as the agile teams are ready to take on more.