2

VISION

Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, and magic and power in it. Begin it now.

—Goethe

QUIZ

To set the stage for this chapter, try answering each of the following statements with Agree or Disagree. Answers appear at the end of the chapter.

Statement |

Agree |

Disagree |

A product vision will emerge over time. |

|

|

Every Scrum Team member should have a clear understanding of who the customers are and how the product generates revenue. |

|

|

Most great products are created by happenstance. |

|

|

A good vision should be free of emotion. |

|

|

Agile is all about getting started; the right product will emerge eventually. |

|

|

It is an advantage to have a technically minded Product Owner. |

|

|

Let’s start this chapter by looking at a couple of example vision statements from fictitious companies.

![]() AnyThreeNow.com, a global mail order service company “Anyone should be able to purchase anything, anytime from anywhere and get it in less than a day.”

AnyThreeNow.com, a global mail order service company “Anyone should be able to purchase anything, anytime from anywhere and get it in less than a day.”

![]() ChaufR.me, a globally operating taxi service “We get you to your destination safely and reliably—as if your parents were driving you. Peace of mind with no wallet required.”

ChaufR.me, a globally operating taxi service “We get you to your destination safely and reliably—as if your parents were driving you. Peace of mind with no wallet required.”

What makes a vision compelling? Let’s borrow a definition from Ari Weinzweig, co-founder of Zingerman’s:

A vision is a picture of the success of a project at a particular time in the future. A vision is not a mission statement. We see [the vision] as being akin to the North Star, a never-ending piece of work that we commit to going after for life. It also isn’t a strategic plan—which is the map to where we want to go. A vision is the actual destination. It’s a vivid description of what “success” looks and feels like for us—what we are able to achieve, and the effect it has on our staff.1

For Zingerman’s, an effective vision needs to be:

![]() Inspiring

Inspiring

All who help to implement it should feel inspired.

![]() Strategically sound

Strategically sound

That is, you have a decent shot at making it happen.

![]() Documented

Documented

You need to write your vision down to make it work.

![]() Communicated

Communicated

Not only do you have to document your vision, but you have to tell people about it too.

This chapter introduces some practices that help create a strong vision.

BUSINESS MODELING

You have a product idea. But where do you start?

Even if you already have a product, do you and the rest of your organization truly understand your customers, their needs, and your value propositions? Do you know how you will make money? What about costs?

In much the same way a business does, you need to invest in the right business model for your product. A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.2 You can apply that same rationale to a product.

Many templates and tools exist for creating business models. One of the more popular tools to engage all participants in a structured way is the Business Model Canvas,3 a single diagram that describes your business

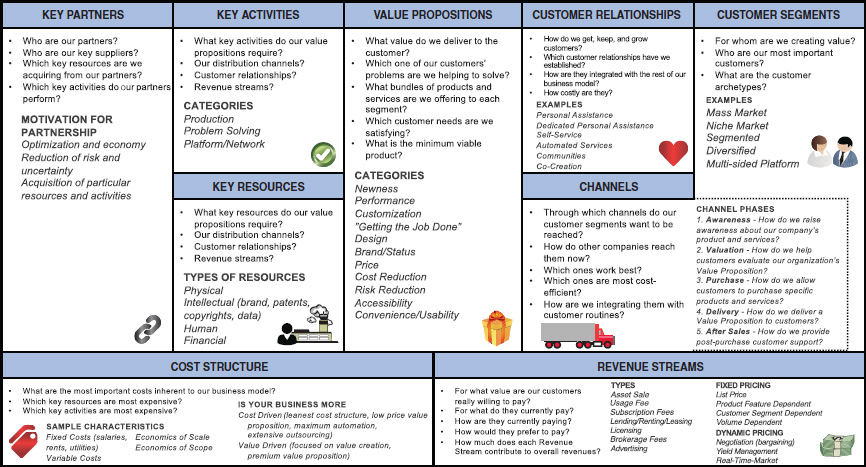

BUSINESS MODEL CANVAS

The Business Model Canvas is divided into nine areas. A group of stakeholders walks through each area while brainstorming both existing and future items.

I like to have people stand around a large canvas or whiteboard and add items on sticky notes that can easily be reorganized. I use a separate color for existing items to clearly distinguish our current situation from where we hope to go. Another tip: taking some time to organize the items in order of importance within each area can also generate some interesting discussions.

I like to have people stand around a large canvas or whiteboard and add items on sticky notes that can easily be reorganized. I use a separate color for existing items to clearly distinguish our current situation from where we hope to go. Another tip: taking some time to organize the items in order of importance within each area can also generate some interesting discussions.

The Business Model Canvas is shown in Figure 2-1. Below it, each area is described in the same order you should work through them with your stakeholders. The first five are linked to revenue (producer benefit). The last four are more about identifying costs.

Figure 2-1 Business Model Canvas

1. Customer Segments

Start here. Who will get value from your product? Individual users, groups, personas, or any relevant stakeholders. Who is your buyer? Who is your consumer?

2. Value Propositions

First understanding who your customers are makes it easier to identify the value propositions for each. What are their needs, and how does your product address them?

3. Channels

You can have the greatest value propositions in the world, but if nobody knows about them, there is no value. Channels are how you intend to get your value propositions to your customers. Advertising? Word of mouth? Search engine? Training? For software products, identifying these is important as they may result in Product Backlog items that are often forgotten.

4. Customer Relationships

This is about retaining your customers and possibly introducing them to additional value propositions. How do you keep them coming back for more? Should you put a loyalty program in place? Maybe a newsletter? Much like with channels, identifying these may introduce commonly forgotten Product Backlog items.

5. Revenue Streams

How do your value propositions generate revenue? What and how much are your customers willing to pay for? Licensing? Membership fees? Advertising? Not every value proposition needs to generate revenue; however, everyone involved with the creation of the product must understand how it eventually makes money.

6. Key Activities

Now that you have identified all the elements for generating revenue, you need to uncover the activities you will have to make an investment in. What will you need to do to make these value propositions a reality? This involves due diligence activities such as market research, legal feasibility, and possibly even patent registration.

7. Key Resources

After identifying what you need to do (key activities), turn your attention to what you need to have. This includes people with the right skills, equipment, offices, tools, and many more.

8. Key Partners

To better focus on your customers and value propositions, there are some things you simply should not do yourself even if you have the ability and money to do them. This is where partnerships come in handy. List them here. Think of hardware providers, service providers, distributors, and similar partners.

9. Cost Structure

Now that you have a better idea of key activities, resources, and partners, you should have an easier time identifying the major investments needed to make this product a reality. Take this opportunity to make these costs explicit.

In addition to using the Business Model Canvas, you might consider other tools in the same space, such as the Lean Canvas4 (a variation of the Business Model Canvas) or the Value Proposition Canvas5 (by Strategyzer, the Business Model Canvas people).

Remember that the main objective of any of these tools is to explore your problem space and to generate discussion among stakeholders. You should not necessarily expect to have a clear vision after this. However, a good business model can provide you with the data necessary to craft that vision. Figure 2-2 presents an example Business Model Canvas for Uber.

Figure 2-2 Example of the Business Model Canvas for Uber

PRODUCT VISION

Visions are tricky. Their purpose is to rally a group of people around a common goal. This is hard to do in a concise way, and many times you end up with some boilerplate buzzwordy statement that does not resonate with anyone (see Figure 2-3).

“We continually foster world-class solutions as well as to quickly create principle-centered sources to meet our customer’s needs.”

“Our challenge is to assertively network economically sound methods of empowerment so that we may continually negotiate performance-based solutions.”

Figure 2-3 Boilerplate product vision statement

Boilerplate statements like these tend to get ignored. A good vision needs to be Focused, Emotional, Practical, and Pervasive.

FOCUSED

Focus involves much more than keeping your vision statement small and concise. Your vision needs to make it crystal clear who the target customer segment is and what your top value proposition is. If you take the time to create a business model, it will provide you with a good place to start crafting a vision. Your business model outlines all possible customers and the value propositions to them. Now you need to make some tough decisions about which ones are the most important.

You do this in much the same way marketing groups approach advertising. They realize that they cannot be all things to all people. Otherwise, they lose focus on what, who, and where to promote their products.

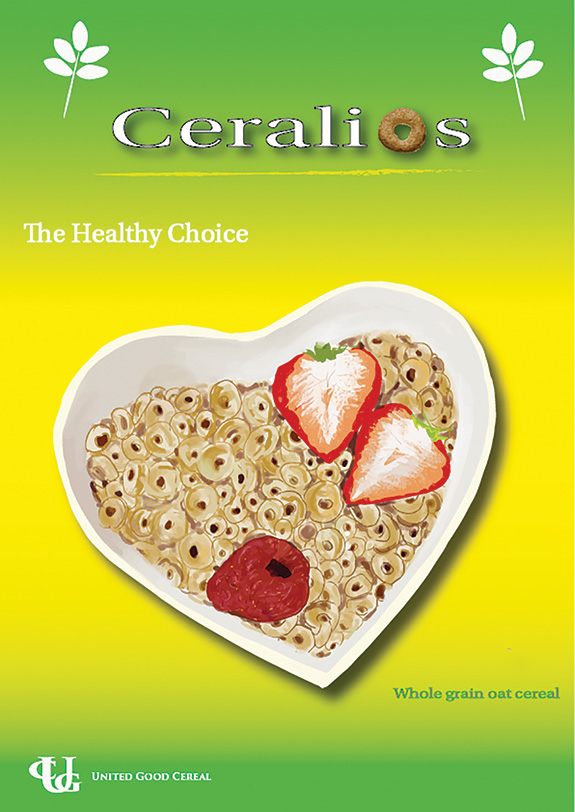

Product Box

Take, for instance, a popular cereal brand called Ceralios by United Good Cereal (UGC). They have many customer segments: young kids, teenagers, college students, parents, health-conscious people, older people—all valid and all pay to use the product. However, UGC simply cannot spend time and energy marketing their product as everything to everyone. The company needs to make decisions. Which television shows should it advertise with? What time of day should it advertise? What shelf should it place its product on in supermarkets?

Take a good look at the box design shown in Figure 2-4 and assess which customer segment was selected as its focus. What is the top value proposition represented by the box design?

Figure 2-4 Ceralios product box

The box is simple, with muted coloring, a focus on whole grain, and a heart-shaped bowl. Is this for kids? No. It was designed for adults and promotes a value proposition of heart health. The box has only seconds to grab a food shopper’s attention away from the hundreds of competing products around it. UGC just needs that one customer segment to pause long enough to pick up the box, maybe turn it around for more information, and then make a decision to buy.

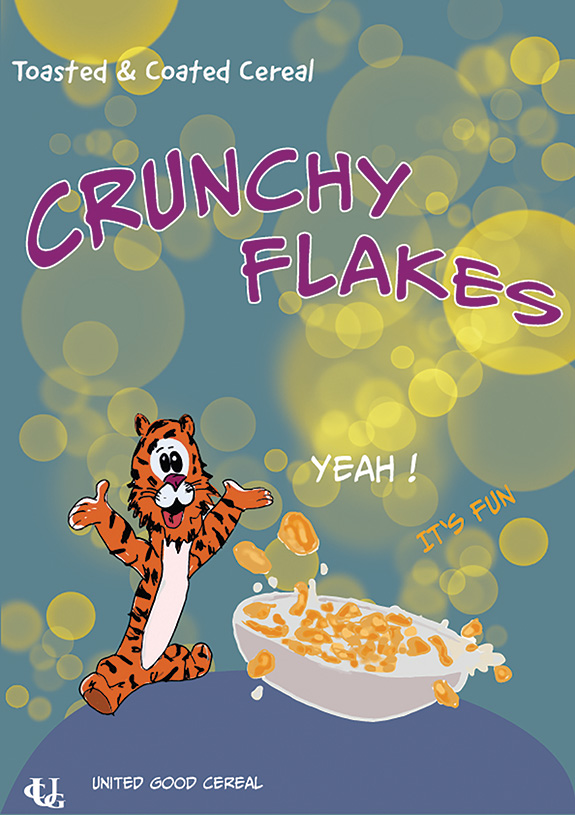

Contrast this product box with the one shown in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5 Crunchy Flakes product box

Which target customer was this box designed for? Brighter colors, cartoon character, no real emphasis on health. It is obviously targeting kids, and the value proposition is much more about fun. Are these any healthier than the previous product which had a focus on heart health? Not necessarily. In fact, what is in the box is kind of irrelevant. Crunchy Flakes has clearly chosen its target customers, who it hopes will point out this box to their parents in the store.

Just like UGC and many cereal brands like them, you can take the same approach for your products. In fact, creating an actual box for your software product, even if it will never be shipped in one, isn’t a bad idea. A popular technique along these lines is the Innovation Games Product Box.6

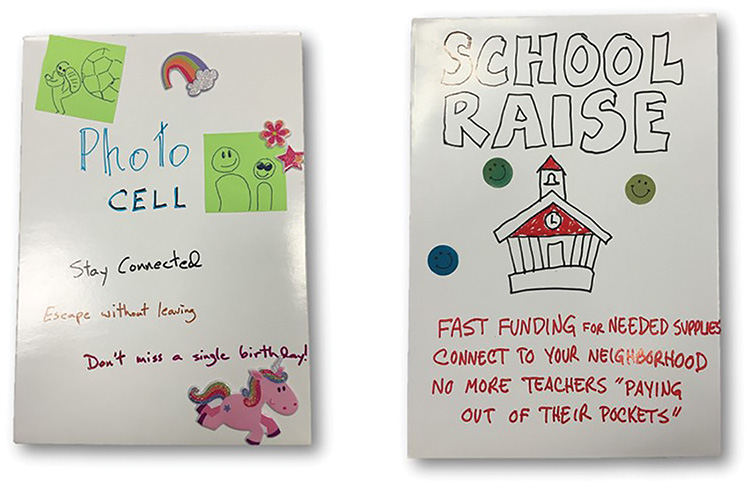

With the Product Box game, supply a group of stakeholders with a blank box and some artistic supplies (colored markers, stickers, magazines, etc.) and ask them to design a box for their product.

The front of the box needs to have the following:

![]() Product name

Product name

![]() Image

Image

![]() Obvious target customer

Obvious target customer

![]() Obvious value proposition for the target customer

Obvious value proposition for the target customer

On the back and sides of the box, game players can add more details about the features and possibly information relevant to different customers. However, the front provides the focus necessary so that the vision is clear.

An important activity for the end of the Product Box activity is to have a representative stand up and pitch his box (and product) to potential stakeholders. The resulting pitch and box produce an effective vision.

Figure 2-6 shows some examples from Product Owner trainings. The left-hand box touts photo sharing for prisoners and their families, and the right-hand box advertises crowdsourced funding for schools.

Figure 2-6 Product box examples from Professional Scrum Product Owner training

Elevator Pitch

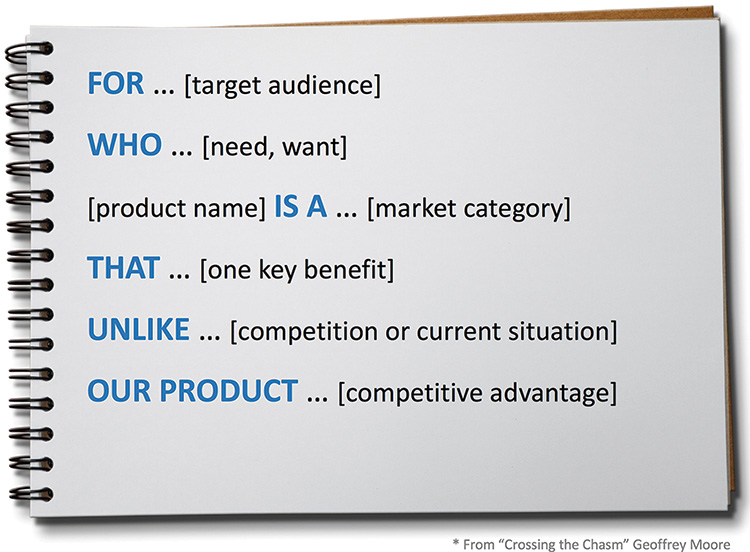

Another common visioning tool that can complement the Product Box is the Elevator Pitch template, made popular in Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm.7

Figure 2-7 Elevator Pitch template

As you can see in Figure 2-7, the Elevator Pitch template focuses on a single target customer and a single value proposition (one key benefit).

The Elevator Pitch template is a good place to start. It ensures you have all your bases covered. However, given that it is a template, it can often feel a little bland and a little long. So, once you’ve filled in the blanks, take some time to distill it into one or two sentences and find a way to make it a little more practical and a little more emotional.

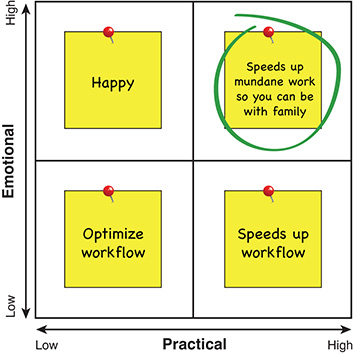

PRACTICAL VERSUS EMOTIONAL

A good vision becomes much more memorable when your audience can imagine themselves doing something (practical) and when it tugs on their heart strings (emotional).

Imagine you have a product that creates efficiencies in an accountant’s workflow.

An initial stab at a vision statement could produce something like this:

It is our business to seamlessly optimize CPA workflow management.

Beautiful, right?

Where would you place the preceding vision on the graph in Figure 2-8?

Figure 2-8 2 Brains: Tell It and Sell It, 2×2 graph

We have room for improvement. Our original vision statement is not very practical or emotional. In what ways will the product optimize the workflow? Will it make it simpler? Will it automate it? Will it speed it up? Which is most important to the target customer segment?

You can make the vision more practical by providing target customers with something they can actually imagine happening. How about this:

Our product speeds up your CPA workflow.

This version of the vision is now practical, but is it emotional?

To inject emotion into a vision, ask yourself how your customer would feel if you were to accomplish “speeding up the workflow.” Happy? Accomplished?

If you simply went with “Our workflow management product will make you happy,” then you lose the practical aspect of the vision (top left part of the quadrant).

You need to make it both practical and emotional. Ask yourself, “What is it about my product that makes target customers happy?” Maybe they won’t have to deal with so much red tape. Maybe they will get home sooner to their families.

Consider a vision statement like that in Figure 2-9:

Our product speeds up the mundane tasks at work so that you can spend more time at home with family.

This statement is both emotional and practical and consequently provides more focus for your teams and stakeholders.

This 2×2 technique is called 2 Brains: Tell It and Sell It,8 from the book Gamestorming.9

Figure 2-9 Emotional and practical vision

PERVASIVE

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

You may have crafted the best vision statement in the world, but if nobody ever hears it, it obviously is not much use. This happens way too often, when a small number of people who understand the vision just assume that everyone else does too. They show frustration when decisions are made that do not reflect the vision. They often chalk it up to lack of buy-in, initiative, or competence. They underestimate the importance of creating a disciplined practice of constantly reinforcing vision, even when it seems redundant to them.

As a Product Owner, it is your responsibility to communicate the vision and ensure it is well understood and adhered to. Fortunately, Scrum builds in many opportunities to do this.

VISIONING WITH SCRUM

Sprint Planning offers an excellent opportunity to remind your team of the vision. Kicking off with a reminder of the vision and how the top of the Product Backlog fits into it is a must. This also helps the Scrum Team come up with a more effective Sprint Goal.

The Sprint Review is an opportunity to reinforce the vision not just with your team, but with your stakeholders.

The Sprint Retrospective is your opportunity to inquire about the effectiveness of your vision communications. Consider asking the following questions in the retrospective:

![]() Is everybody on the team comfortable with the vision?

Is everybody on the team comfortable with the vision?

![]() Is our vision still relevant?

Is our vision still relevant?

![]() Which actions from the last Sprint reflect the vision? Which do not?

Which actions from the last Sprint reflect the vision? Which do not?

![]() Do our stakeholders understand the vision? Which ones do not?

Do our stakeholders understand the vision? Which ones do not?

![]() What are some ways to improve our vision communication?

What are some ways to improve our vision communication?

Disclaimer: I have found that all this constant droning on about the product vision can annoy my team and stakeholders. Lots of eye rolling. But I’ve learned not to feel bad about it. I now own it. This is often what is needed to keep the vision front and center in everyone’s minds. I compare this to a parent constantly repeating the same messages about safety, grades, cleaning up, and so on. It eventually does sink in, and the children preach the same messages to their kids later in life. Another tactic to communicate the vision and ensure it is well understood and adhered to is to find ways to make the vision statement visible in the team’s work area.

Disclaimer: I have found that all this constant droning on about the product vision can annoy my team and stakeholders. Lots of eye rolling. But I’ve learned not to feel bad about it. I now own it. This is often what is needed to keep the vision front and center in everyone’s minds. I compare this to a parent constantly repeating the same messages about safety, grades, cleaning up, and so on. It eventually does sink in, and the children preach the same messages to their kids later in life. Another tactic to communicate the vision and ensure it is well understood and adhered to is to find ways to make the vision statement visible in the team’s work area.

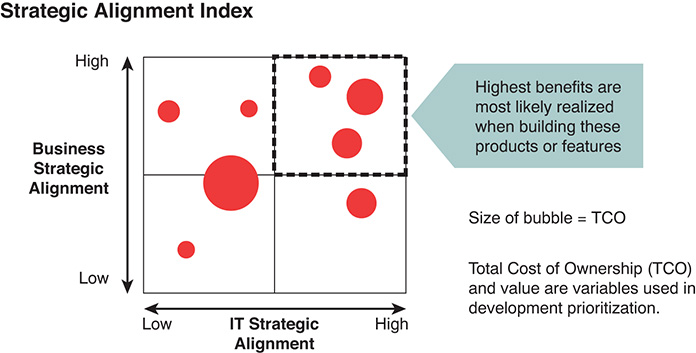

TECHNICAL STRATEGY

Much of the discussion so far has been about business strategy.

It is quite common for Product Owners to stay with this line of thinking. However more and more, technical strategy is becoming a bigger part of the role (see Figure 2-10).

As mentioned in the previous chapter, there are two types of products: (1) the end business product that the customer is ultimately paying for and consuming; and (2) the software product, which is often the channel used to access the business product. An example would be a savings account (business product) that yields a certain interest rate and the mobile application (software product) that allows the customer to access the product.

These days it is the software product landscape where companies are increasingly competing. At a certain point, it isn’t your interest rate that attracts customers to your financial product; it is whether you have a useable mobile app and website.

Figure 2-10 Strategic alignment (Source: “Measuring the Business Value of Information Technology,” Intel Press.)

What does this have to do with you, the Product Owner? Well, it should be your responsibility to also understand and promote the technical direction of your product. If you come from a technical background, this may be easier. If not, leverage the knowledge on your Development Team and within your stakeholder community.

There is no need to be coding along with your team. In fact, getting too involved in solutions could be quite harmful to your role. A Product Owner needs to focus on the “what” (strategy), not the “how” (tactics).

Consider this quote from the Forbes article “Great CEOs Must be Either Technical or Financial”:10

Technology skills do not necessarily mean hands-on skills, though they can arise from hands-on experience. It means simply understanding the technical state of play in the environment in a way that you can make exceptional decisions.

Technology changes suddenly expand the strategy canvas and offer new ways of doing old things, or entirely new things to do.

Some strategic questions a Product Owner should be considering are these:

![]() What are some of the latest technologies that we should be taking advantage of?

What are some of the latest technologies that we should be taking advantage of?

![]() Should we be in the cloud?

Should we be in the cloud?

![]() Would wearable devices like watches add value?

Would wearable devices like watches add value?

![]() What about opening our API up to the public?

What about opening our API up to the public?

![]() Native iOS or HTML5?

Native iOS or HTML5?

These are all technical yet exceedingly strategic decisions that need to be made.

It is important to understand that there is a timing aspect to consider. Features that align perfectly to your business strategy and IT strategy today may not align in the future. Priorities shift over time. Sometimes the most strategic move is to stop and to refocus your investment. Consider ramping down or even retiring products altogether.

Discontinuing a product can be a healthy business decision. Remember the following products from successful companies?

![]() Apple Newton

Apple Newton

![]() Apple iPod classic

Apple iPod classic

![]() Google Glass

Google Glass

![]() Google Wave

Google Wave

![]() iGoogle

iGoogle

![]() Google Reader

Google Reader

![]() Amazon Fire Phone

Amazon Fire Phone

QUIZ REVIEW

Compare your answers from the beginning of the chapter to the ones below. Now that you have read the chapter, would you change any of your answers? Do you agree with the answers below?

Statement |

Agree |

Disagree |

A product vision will emerge over time. |

|

|

Every Scrum Team member should have a clear understanding of who the customers are and how the product generates revenue. |

|

|

Most great products are created by happenstance. |

|

|

A good vision should be free of emotion. |

|

|

Agile is all about getting started; the right product will emerge eventually. |

|

|

It is an advantage to have a technically minded Product Owner. |

|

|

____________________________

1. Ari Weinzweig, “Why and How Visioning Works,” Zingerman’s, accessed February 16, 2018, https://www.zingtrain.com/content/why-and-how-visioning-works.

2. Alexander Osterwalder et al., Business Model Generation (self-published, 2010).

3. “The Business Model Canvas,” Strategyzer, assessed February 17, 2018, https://strategyzer.com/canvas/business-model-canvas.

4. Ash Maurya, “Why Lean Canvas vs Business Model Canvas?,” Love the Problem (blog), February 27, 2012, https://leanstack.com/why-lean-canvas/.

5. “The Value Proposition Canvas,” Strategyzer, assessed February 17, 2018, https://strategyzer.com/canvas/value-proposition-canvas.

6. “Collaboration Framework: Product Box,” Innovation Games, accessed February 17, 2018, http://www.innovationgames.com/product-box/.

7. Geoffrey A. Moore, Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling Technology Products to Mainstream Customers (New York: Harper Business, 1991).

8. “2 Brains: Tell It and Sell It,” Gamestorming, assessed February 17, 2018, http://gamestorming.com/games-for-design/2-brains-tell-it-sell-it/.

9. David Gray, Sunni Brown, and James Macanufo, Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers (Beijing: O’Reilly, 2010).

10. Venkatesh Rao, “Great CEOs Must be Either Technical or Financial,” Forbes.com, March 9, 2012, https://www.forbes.com/sites/venkateshrao/2012/03/09/great-ceos-must-be-either-technical-orfinancial/#479cf37a63c6.