Workers, Managers, and Leaders

Leadership is different from management, but not for the reasons most people think.

—John P. Kotter (1990, p. 103)

People generally do not understand the essential differences between leaders and others. Much of what they do know is wrong and problematic. Because coaches are often called upon to help line workers make the transition from follower to manager and to help managers move into leadership, it is essential that coaches clearly understand the different sets of skills and behaviors required at each level. Many executives have not thought much about the distinctions between leadership and management. The old industrial paradigm sees leadership as simply excellent management or management that is particularly popular or effective or even charismatic.

The skills and the differences between leadership and management are not generally taught in school, and people are supposed to pick them up, somehow, as they move through their career. This is impossible to accomplish without independent study, partly because of myths related to the leadership function, myths like the following:

Myth: Leaders are born, not raised.

Myth: Leadership skills develop naturally as one moves up an organization and takes on more responsibility.

Myth: You must thoroughly understand (and preferably master) the content skills of those you lead.

Myth: Before you become a leader, you must learn how to be an excellent follower.

Myth: Managers must be leaders.

Myth: What we really need is more leadership and less management.

Myth: Real leadership cannot be taught.

Myth: There is no unique set of leadership skills. It is common sense, and for the most part, consists of good personal and work habits combined with some natural charisma.

Myth: Managers and leaders do about the same thing in an organization, just at different levels (and for different compensation).

These myths create problems for organizations, as they inhibit good leadership as well as good management. It is clear that leadership skills can be learned by motivated learners. It is also clear that, as John Kotter (1990, p. 109) puts it, “the on-the-job experiences of most people actually seem to undermine the development of attributes needed for leadership.” There is little evidence that good followers make good leaders. The required skill sets seem to be nearly independent of each other. Some great leaders have been notably poor followers (George Patton being the paradigm example). In today’s business culture, there is virtually no way that leaders can possess the technical skills of those they lead. The requisite skills change too quickly. Do you suppose that Bill Gates or Steve Jobs can still write useful computer programming code? Can the CEOs of video gaming companies skillfully play the games their companies produce? Can deans of dental schools still perform complex procedures such as root canals or the new skills required to place implants? Leaders and managers perform uniquely different functions using different sets of skills, and both are crucial to organizational success.

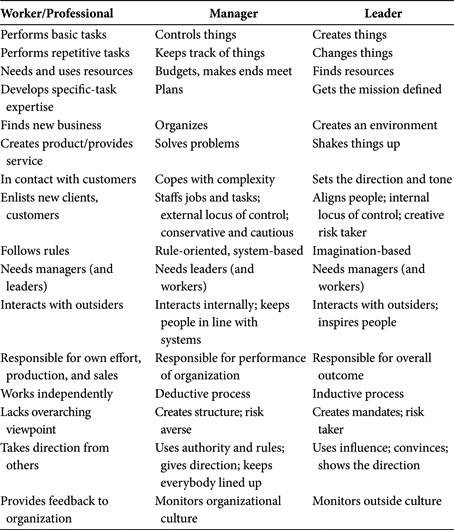

The last myth on the list—that managing and leading are essentially the same—is the one that coaches must thoroughly debunk. Coaches are often called upon to help a bright, promising executive move from worker to manager and from manager to leader. They must be able to teach clients the important differences and help them develop leadership skills that will enable them to excel. In fact, the skills that make for a great line worker might actually get in the way of someone in the manager’s role, and the skills and personality of a terrific manager can be counterproductive when that same person is thrust into the leadership role. Sometimes content skills distract a leader who should be focused on strategy and the future. Other times terrific managers can make a mess by micromanaging rather than delegating. The following section outlines some important distinctions between workers, managers, and leaders in a typical hierarchical organization. Table 16.1 summarizes these differences.

Table 16.1 Differences among Workers, Managers, and Leaders

Differences among Workers, Managers, and Leaders

The Line Worker or Professional Worker

A review of the essential skills required by workers at the entry level is called for. There are extensive sets of personal habits and behaviors that ought to be in place before a competent worker shows up for work. This is not always the case, and coaches can certainly help workers identify and develop the necessary skill set. For example, most people are not born with all of the skills required of a successful salesperson, even though they might possess excellent prerequisites. Certain other skills, such as project management skills, are essential because they are the fundamental basis for the organization’s success. New customers and new clients must come in, and work must go out. Employees must possess energy to get things done, and they need basic communications skills, basic content skills, and basic computer skills. They must be well organized and reliable. Some jobs require extraordinarily complex skills and a strong drive to succeed. Some jobs require workers to develop a serious special expertise. Employees must be adequately loyal to the organization and its goals, even when they do not agree with current tactics. Leadership requires competent followers. They need to be willing to be told what to do, and to “follow orders” sometimes when the orders do not make sense or when they disagree with the instructions. They need a positive attitude to be able to see things in a good light and to behave pleasantly. Increasingly, workers must be able to make a good impression with customers through a service orientation and the willingness to go the extra mile to provide exceptional customer service. They also need to be able to provide feedback to the organization when something is amiss or is being done poorly. They need to be reasonably well organized and able to cope with paperwork efficiently. They have to be able to learn new tasks as demand arises. They must avoid the destructive behavioral traps of substance abuse, sexual harassment, overwhelming stress, and entangling office romance. They must be able to effectively manipulate the written word and use the latest technology. And they need to be able to get things done and see projects through to their completion. These are all basic worker skills required in the 21st century.

The Manager

Managers seek order and control, and are almost compulsively addicted to disposing of problems even before they understand their potential significance.

—Abraham Zaleznik (1992, p. 131)

Managers, as Abraham Zaleznik wrote in the Harvard Business Review (1998,p. 61), “ensure that an organization’s day to day business gets done.” Managers are about control. They create order out of potential chaos and translate the leadership’s vision into productive reality. They tame complexity. They direct people, reinforce desired behavior, and punish that which does not conform. They are the gatekeepers and often say “no” when an idea is out of conformity with the system. They limit things and they dislike disorder. They make sure that the organization has “the right products in the right places at the right time and in the right quantity” (Sloan, 1964, p. 440). They regulate and safeguard the company’s resources, and pay close attention to what is happening in the present moment. They know where everything is, and they work hard to meet established goals. They set goals that are aligned with organizational strategy as they understand it. Much of what they do and think is data based these days, and they rely on spreadsheets and the details found on them. They are highly interested in what leadership is thinking and are likely to be involved in bureaucratic politics and intrigue. They know where the bodies are buried. When something works, they keep doing it, and they can be hostile to change, for change is unpredictable and it causes them problems. They have systems in place that have worked well, and changes force them to adjust their systems.

The managerial personality is best when it is calm, rational, and analytical. Managers are tolerant but demanding. They are on the lookout for problems, for shortages, and for deviation from the system. The successful ones are diplomatic. They are sensible and reliable. They tend to be realists, and they do not like risk (nor should they). Managers are focused on how and whether things get done rather than why or even what. Tell them what needs to be done and they will find a way to get their system and people to do it.

None of this is meant to disparage managers or managing. Excellent management is essential for organizational success; it is rare and difficult to do. Recent business literature and training have given the impression that leadership is a good thing and that management a something of a bad thing (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). In this view managers are associated with bureaucracy, and that is seen as bad. Leaders save the day by cutting through red tape and creating action. Good management, however, creates systems that work, and people rarely complain about those. Nor do managers get much credit. Management is not as glamorous as leadership, that’s for sure, but is exceptionally important. If you have a great idea and hard-working employees but you cannot get a product to market, you fail. If you have a great product but you cannot get it delivered on time, what is the point? If your resources are squandered through laxness, how could your organization possibly succeed? Leadership can motivate people to try harder, but a good system is required. What good is a mayor who charismatically urges good public transportation if there is no one in place who knows how to get such a complex system started and managed?

Although good management is not as rare as good leadership, it is not common. Managers organize and coordinate complex systems that are essential to our well-being. Disorganization and poor coordination drive people crazy, damaging morale and running customers off. Organizations need effective management to survive and succeed.

People hate to work for dictators, and the set of personal and functional skills required by effective managers is extremely valuable. Humane efficiency is worth its weight in gold, yet it is often taken for granted.

Effective managers are a joy to behold and a pleasure to work with in any organization. People love to work for well-organized managers who facilitate getting the job done by coordinating the work of various people, and they hate to work for managers who are ineffective, uncoordinated, or incompetent. (Rost, 1991, p. 106)

Managers certainly exhibit leadership behaviors (such as interpersonal influence), but those behaviors are not necessarily found in their job description nor are the behaviors essential to their function. Those behaviors are often helpful but sometimes counterproductive. Although a manager might be charismatic, and his or her charisma might be helpful, it is not an essential component of effective management performance. Sometimes the charisma of a manager can get in the way, causing jealousy and resentment from above. Managers might be visionaries, but that is not an essential management quality. Although it is often best to influence subordinates, a manager influences people to conform to a system that is in place, not to change the basic arrangements. When a manager influences people to work harder or to do things in a new way, he or she is using leadership skills, but this is not a leadership function. When everyone in an organization exercises leadership, the resulting changes must still be coordinated and managed.

Of course, leadership from many sources does not necessarily converge. To the contrary, it can easily conflict. For multiple leadership roles to work together, people’s actions must be carefully coordinated … by strong networks of informal relationships. (Kotter, 1990, p. 109)

Leaders, hopefully, have established a culture with overarching mores and formal and informal relationships for followers. Too much leadership behavior (in the wrong places) can create the very chaos that managers are paid to control.

The Leader

Leadership is not equivalent to office-holding or high prestige or authority or decision-making. It is not helpful to identify leadership with whatever is done by people in high places.

—Joseph C. Rost (1991, p. 98)

In addition to the information in the previous chapter, here are some observations about leadership that will help differentiate it from managing. Leaders are responsible for the overall outcome, and they determine the overall direction for the company. They create the organization’s vision, and they align people and things to realize that vision. They create a process by which the social order of the organization is formed or shifted (Rost, 1991). Their focus is usually on change. They sometimes create chaos that managers then have to clear up. Leaders influence the reality and direction of an organization. Although management can coerce you, you must volunteer to be led.

Classic leader behaviors include breaking paradigms, motivating people to see things in a new way, causing others to shift priorities, and disrupting the status quo. Good leaders are not always comfortable to be around or to hear. They can disturb and frighten. They upset things; they point out faults in the way things are. They intend real changes (Rost, 1991). They do not always make everyone happy.

Although there may be times when minimal leadership is required, in the present modern environment, where change seems rapid and normal, leadership takes on an essential role. It is a rare organization that can survive by simply doing something well for long periods in the same ways. Other companies catch up or find a better way. Frequently, market dynamics change. Stagnant organizations get left behind in a hurry these days.

Leaders tend to be restless as a personality style. They love change and hate mundane, repetitive work. They like to use their imagination and they trust their own intuition. They enjoy being alone and like to reflect on things. They are comfortable with risk and understand its role and importance. They tend to be competitive by nature, and this translates into a desire to be “the best,” to be on top of the heap. Competition gets their juices flowing. Sometimes they act without thinking things through. They do not always realize that they must follow all of the same rules as everyone else. Their work life and workplace might even be disorganized, so they hire someone to organize them.

Although it is a plus when leaders are also good managers, it is not essential. If real leaders are rare, then real leaders with good management skills are even more rare. An organization simply cannot wait around for such a person to evolve, so it hires a leader (or follows an emergent one) who lacks management skills. (A common alternative is to choose an excellent manager on the assumption that he or she will turn out to be a good leader. This works well in some cases, not so well in others.) It is then essential to hire excellent managers to complement and administer the leader’s vision. In many cases, great leaders could never put their ideas into practice (or if they could, it would not be for long), and great managers could never think up the ideas that they are now managing. Leaders and managers need each other.

Leaders communicate with organizational outsiders. They present the vision and image of the organization to stockholders, funding sources, government agents, board members, industry leaders, and the public. They pay attention to the interests of those parties and bring feedback to the organization so that adjustments can be made. They manage boards. They establish life-or-death interpersonal relationships with important outsiders. Effective leaders are able to create trusting relationships that become resources in times of trouble.

Leaders do one more thing that is not typically associated with the management function: They think. They reflect, they synthesize, they develop and use their imagination. They take in information from wide-ranging sources (including newspapers, the Internet, colleagues from other companies and industries, and best-selling books). They integrate new ideas into the organization they lead. Managers have no time to think. They are paid to be on top of the details, resources, and deadlines. They do not have much time, and they are not paid to take time. Leaders, in contrast, are paid to reflect.

Please refer to Chapter 15 for a detailed review of the general literature on leadership and the conclusions that can be drawn from it.

There are alternatives to the traditional view of the hierarchical organization. Newer versions of business organizations stress a flatter, more matrixed structure, with shared responsibility for leadership throughout the organization. Each member of the company team is responsible for providing vision, motivation, and direction. Such a structure can be enormously effective in some markets and environments. But it is probably not suitable for all business situations, and it often does not survive as a company matures.

Similarly, many managers find it important to serve as leaders of those who report to them. Certainly they must motivate and find creative ways to accomplish their tasks. Nonetheless, most of the critical leader functions are still most appropriate for those in leadership positions.

Leadership coaches are hired for two reasons. They are either paid to help “fix” problem people (or remediate deficits) or they are brought in to help a person make the transition from one career step to another. Sometimes they are hired for the specific purpose of helping a promising leader to emerge successfully.

Coaches thrive most when they are seen as an essential component in the developmental process of the organization’s leadership. If you (as an individual) have a coach, the organization sees you as having promise and is willing to invest in your transition from worker to manager and from manager to partner or leader. The distinctions between these roles offer an important opportunity for the coach.

Most organizations are poor teachers of leadership, and few are organized to grow real leaders. Many actually punish those with real leadership inclinations. The leadership literature points out that people desiring leadership development cannot learn their skills in school or at institutes or by reading leadership books (although these activities certainly help). They need to have guided leadership experiences and they need help to learn from their own inevitable mistakes. They need to be able to grow as a result of their developmental difficulties. They require challenging assignments early in their career, and they can use extensive mentoring and time for reflection. They need good, hard-hitting feedback, delivered in a way that helps and does not hurt. A coach can be of enormous help in this ongoing process, especially when in-house mentors are not available.

In 1997, Witherspoon and White wrote a defining booklet on executive coaching at the Center for Creative Leadership (Four Essential Ways That Coaching Can Help Executives). They describe the following four essential roles that coaches can play. These roles should be contemplated and discussed with clients early in the coaching relationship.

Coaching for Skills

Witherspoon and White (1997) recommend skills coaching when workers (and occasionally managers or leaders) need quick help to learn an important skill. This process can start from the basis of a self-perceived deficit or as the result of an assessment. Examples of such skills include public speaking, listening, personal organization and time management, presentation of self (appearance or behavior), teaching how to cold-call, and even providing an in-depth understanding of the product or service that the organization offers. Sometimes a professional becomes aware that he or she is not “coming across” effectively. Coaches can perform an assessment, present the results, collaborate in the creation of a learning plan, and help the client put his or her learning into effect. This aspect of coaching tends to be brief and circumscribed. When the executive learns the skill, the coaching is finished.

Coaching for Effect

Coaching for effect focuses on the executive’s current job and his or her performance in it. Such coaching is appropriate for managers who face difficult obstacles. Clients often do not know what is wrong or lacking, but they have reason to believe that they need to improve what they do. This form of coaching is more comprehensive, and it, too, begins with an assessment, but this assessment is likely to seek input from a wide range of sources. A 360-degree evaluation is often useful. It tends to be intermediate in time span, lasting over several months or as long as a year. It has specific goals, and the goals are organizational in nature. For example, the coach and client will know that they are successful when specified organizational outputs improve. Coaching might focus on analytical skills or tasks, problem-solving measures, team building, organizational architecture, or operations management problems. Such a coach must possess expertise in the arena of focus or at least be able to locate someone with task-specific skills for consultation.

Coaching for Development

Coaching for development is appropriate for workers, managers, and leaders alike. It strives to prepare a person to move to the next level. It involves an analysis of the essential skills required for the future, an evaluation of skills in place, and a comparison of the two. The coach and client work together to develop those necessary skills and the experiences required to gain them. As Witherspoon and White (1997) point out, it may even involve the unlearning of a behavior that was once useful but will be a liability in the future. The goals may be less clear and more personal in nature, and they might even involve an examination of where the client wants to go with a nascent career. It might call for a clear-eyed look at client goals to determine whether they are realistic and attainable.

Coaching for the Executive’s Agenda

Coaching for the executive’s agenda is most closely related to the leader function. A coach can be used by a leader to help that leader develop and to help him or her evolve the organization. This role is likely to be ongoing, with ambiguous and ambitious goals. The coach may be available regularly or on an as-needed basis. He or she may help the leader to think things through, to reflect, to make decisions, and to provide support when problems get difficult or the process gets lonely. The coach can act as a sounding board and reality test. For a detailed explanation how to do this, along with a discussion of expectable challenges, see Nadler’s (2005) essay in the Harvard Business Review.

- Management and leadership are different, and the relationship between the two is widely misunderstood. Coaches can bring useful clarity to an organization, even in modern “flat” organizations.

- Coaches can help clients move from one level to another. It is nearly impossible to learn adequate management and leadership skills without mentoring and challenging growth experiences. You cannot learn to ride a bicycle without getting on and falling off a few times. Most organizations do not provide effective mentoring from within. Mistakes will be made, and coaches can serve as important mentors and teachers in this process.

- Coaches must help clients accurately determine the appropriate purpose for coaching and then apply the right interventions. Significantly different interventions are useful in different circumstances. Coaching for leadership is different from coaching for management or coaching for sales skills. One coach cannot possibly fit all of these situations.

- The role of coach as developmental mentor is important (to the coach), for it removes him or her from the negative role of remediator of “losers” or people the organization will eventually shed. Coaching can be a resource for “fast-track” people.

- Most organizations do not breed leaders. Coaches can help them create a leadership development culture.

- Not everyone is suited to be a leader, and many people are not willing to do the things that leaders do. Excellent managers should think twice before taking a leadership position (even if the money is attractive).

Bennis, W. G., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategy for taking charge. New York: Harper & Row.

Kotter, J. P. (1990, May–June). What leaders really do. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 103–111.

Nadler, D. A. (2005, September). Confessions of a trusted advisor. Harvard Business Review, 83(9), 68–77.

Rost, J. C. (1991). Leadership and management. In G. R. Hickman (Ed.), Leading organizations (pp. 97–114). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sloan, A. P. (1964). My years with General Motors. New York: Doubleday.

Witherspoon, R., & White, R. (1997). Four essential ways that coaching can help executives. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Zaleznik, A. (1992, March–April). Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, 126–135.

Zaleznik, A. (1998). Managers and leaders: Are they different? In Harvard Business Review on leadership (pp. 61–88). Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Bennis, W. G. (1977, March–April). Where have all the leaders gone? Technological Review, 3–12.

Bennis, W. G. (1989). On becoming a leader. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bennis, W. G. (1989). Why leaders can’t lead. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Goffee, R., & Jones, G. (2006). Why should anyone be led by you? Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Goleman, D. (1998, November–December). What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 93–102.

Harvard Business Review on leadership. (1998). Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Mintzberg, H. (1990, March–April). The manager’s job: Folklore and fact. Harvard Business Review, 163–176.

Phillips, D. T. (1998). Martin Luther King, Jr. on leadership. New York: Warner Books.

Syrett, M., & Hogg, C. (Eds.). (1992). Frontiers of leadership, an essential reader. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Weinstein, B. (2000, August 27). What a techie gives up to be a manager. San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle, p. CL 23.