A WORD TO THE NERD

The Internet: How Cloud Gets Loud

As Douglas Adams said about the universe, the Internet is big, really big; you won't believe just how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. On a typical Sunday, as I'm writing this, internetlivestats.com estimates that the world's 4.5 billion Internet users have fired off around five hundred million tweets, performed four billion Google searches, sent nearly two hundred billion emails, and moved an astounding five quintillion bytes of data (that's five billion billions!) across the countless cables that connect our computers, phones, televisions, and, well, pretty much everything.

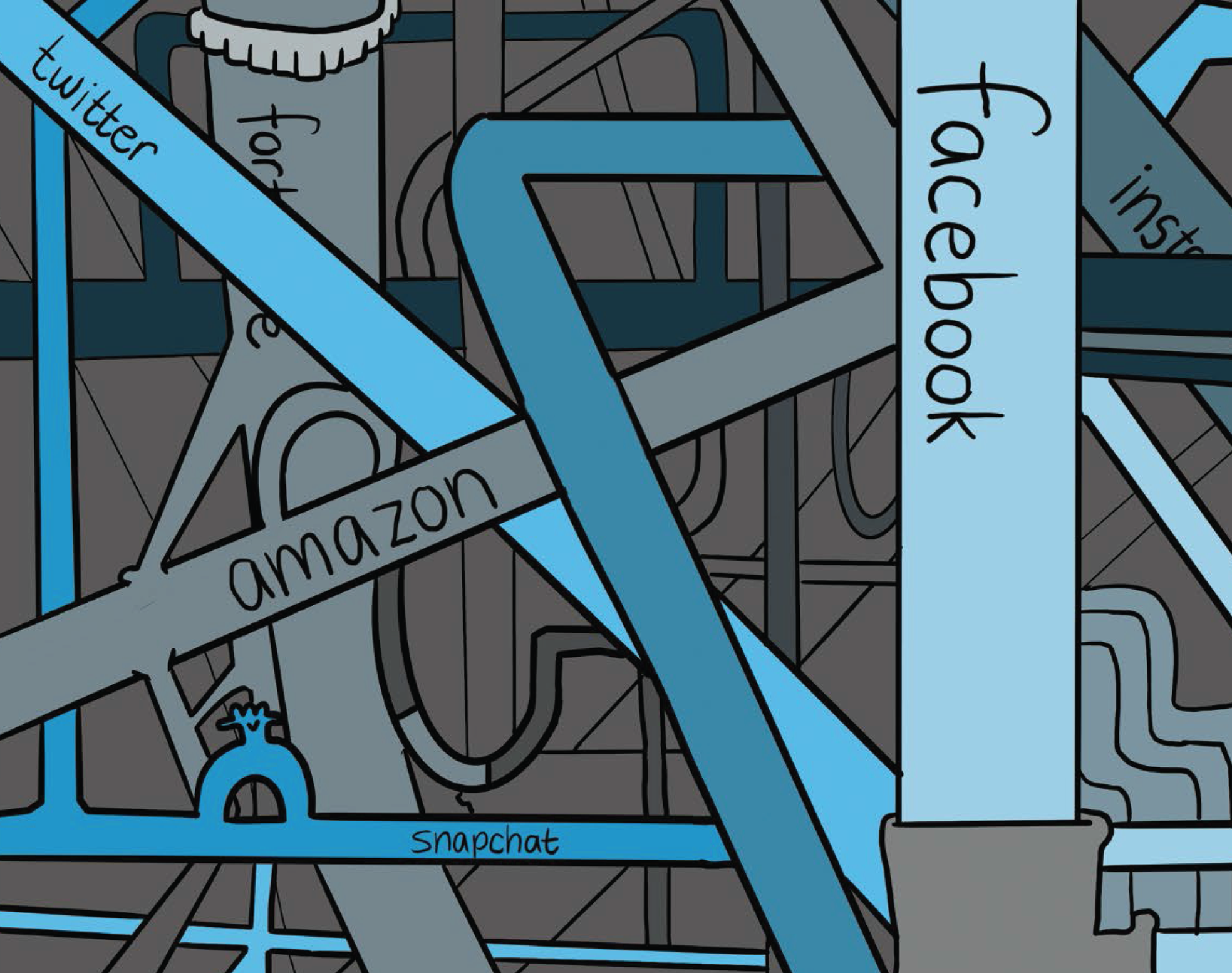

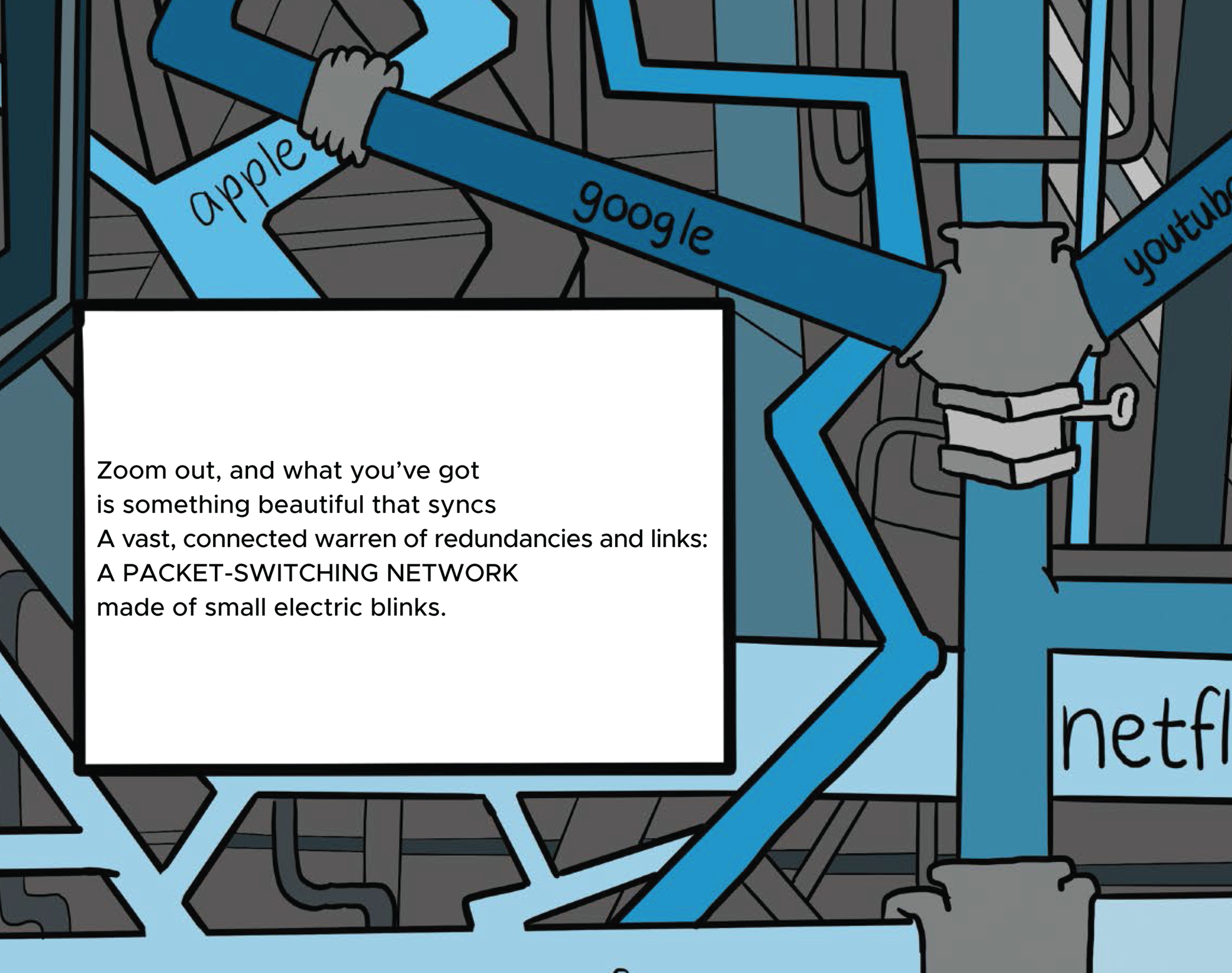

Packet-Switching Networks

It's not strictly true that the Internet was intended as a communication network that could withstand a nuclear strike—in its first incarnation, it connected only four computers, all at research universities on the West Coast. (The first message sent over the new network, dubbed ARPANET, consisted of two letters: “LO.” That sounds appropriately heraldic, though really researchers were trying to send the word “login” until the computer crashed.) But still, it was the 1960s, the Cold War was always a hot topic, and the early Internet engineers were military-funded and thinking existentially.

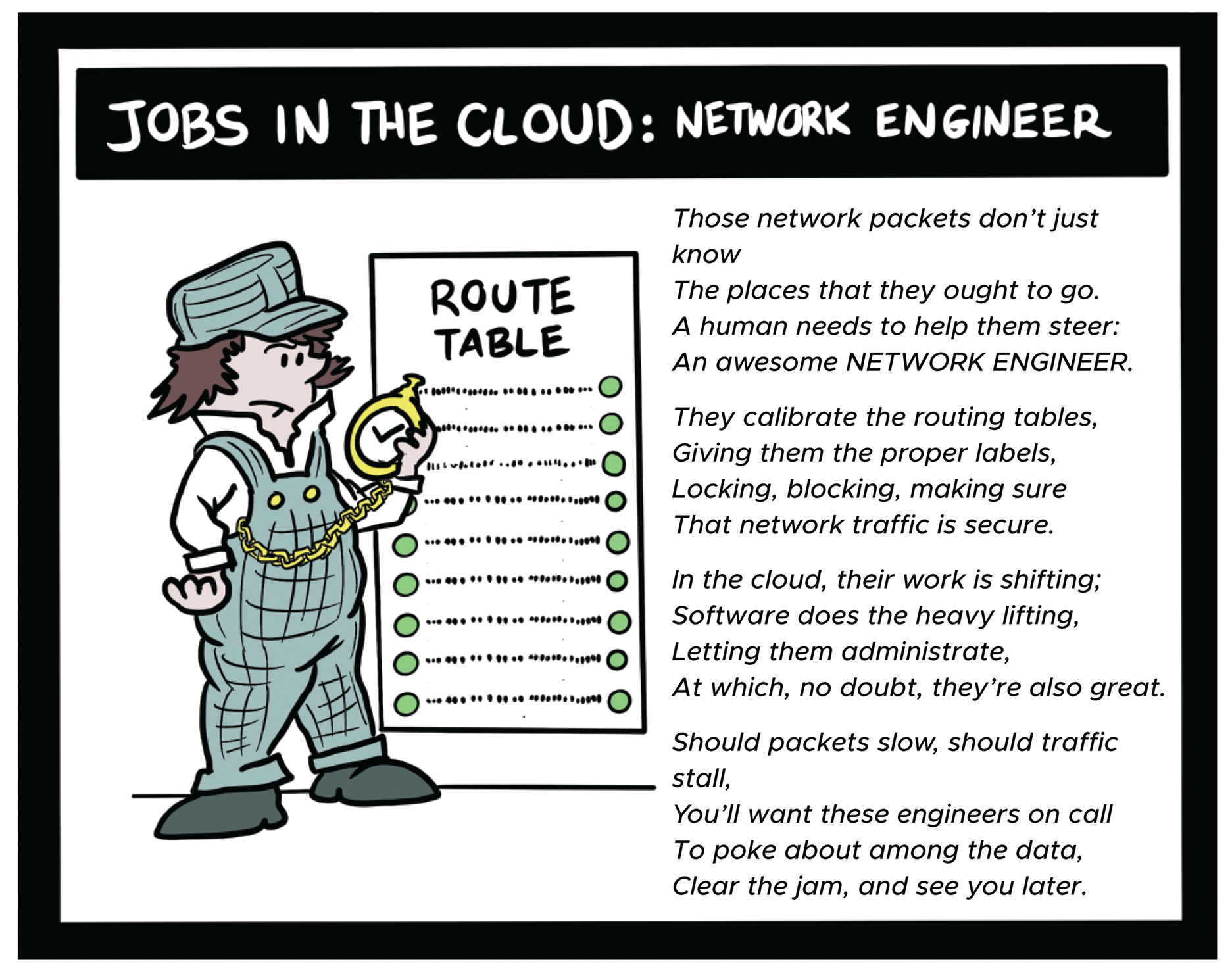

That's why the Internet doesn't have a central clearinghouse, like an old-fashioned telephone switchboard, that all traffic must pass through. Instead, the network is deliberately decentralized by using millions of specialized networking devices called routers, each with its own map (a route table) of places to forward traffic.

Internet traffic itself breaks down into tiny chunks of data called packets. Each packet can take a different route to its destination, sometimes traversing several different “hops” between routers along the way. If one router were to disappear, say because Khrushchev got frisky with some ICBMs, theoretically other parts of the network could continue communicating as the routers ping each other and figure out new traffic paths in real time. This is what we call a packet-switching network, and it has changed the world forever.

Internet Protocol

If you've been a citizen of the Internet for any length of time, you've probably encountered the notion of an IP address, which is the string of numbers and punctuation that identify your computer online.

IP stands for Internet Protocol, and it's more than just numbers. IP defines the structure of a data packet. IP addresses identify each packet and tell them where to go. All Internet routers and switches must understand IP to ensure that packets reach the correct destination.

Internet Protocol is that rare beast in the tech world: a universal standard. Everything speaks IP. Voice chat? That's voice-over-IP (VoIP). Remote desktops? PC-over-IP (PCoIP). Learn IP, and you have grasped the core of the Internet. The rest of the networking technologies fit around it like melee diamonds around the central jewel in a ring.

The Networking Stack

Most introductions to computer networking start by trying to explain something called the OSI model, which is a list of seven “layers” of networking, some of which are basically fantasy. Nobody worries about all seven of those layers in the real world. These are the important ones for you to know:

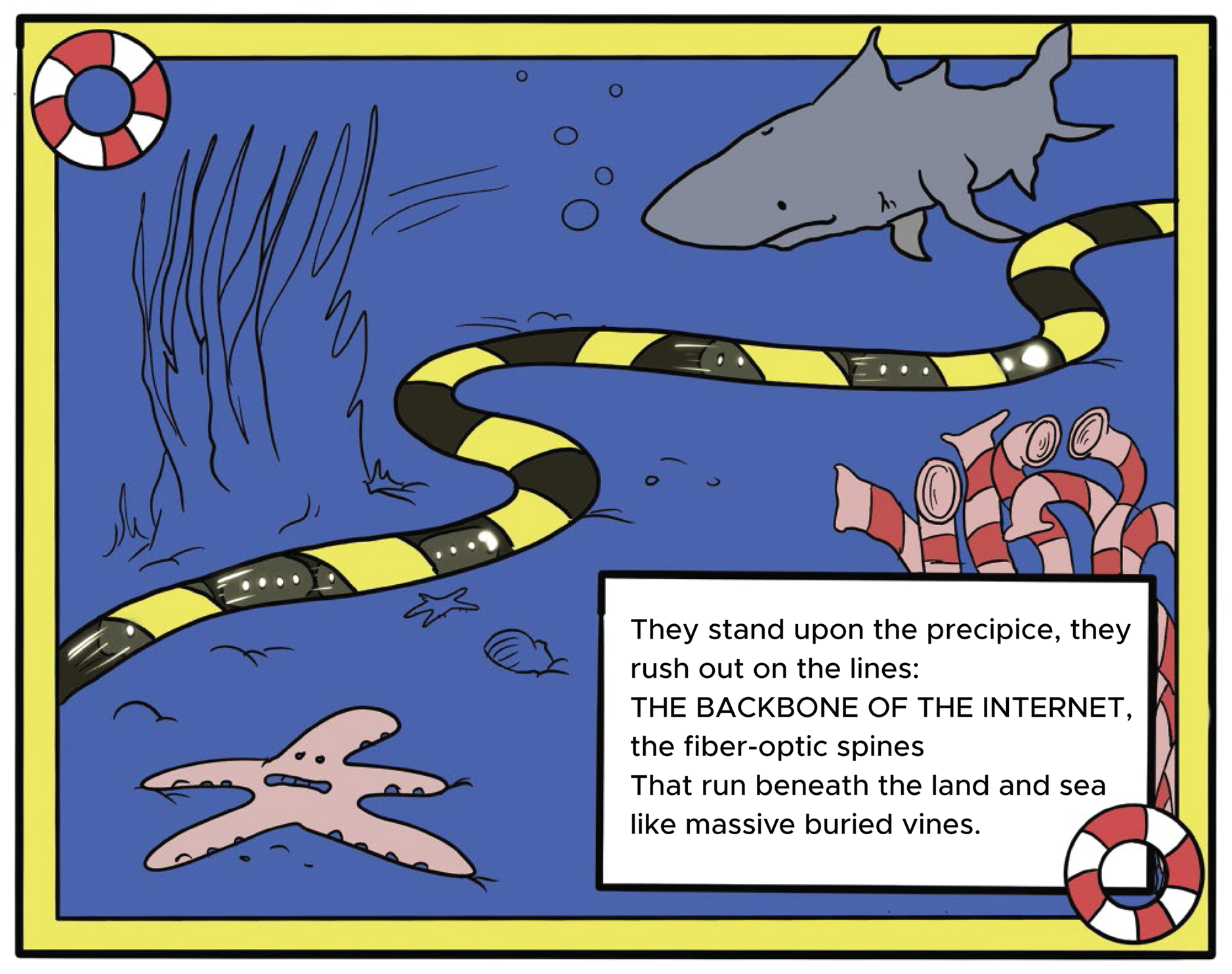

- The physical layer: The actual cables and switches that carry the electrical pulses of communication. If a shark bit through one of the undersea cables that make up the “backbone” of the Internet, which has happened, that would be a physical layer problem (as well as a shark intestinal problem).

- The network layer: IP. This takes care of how packets are packaged up and routed between network nodes.

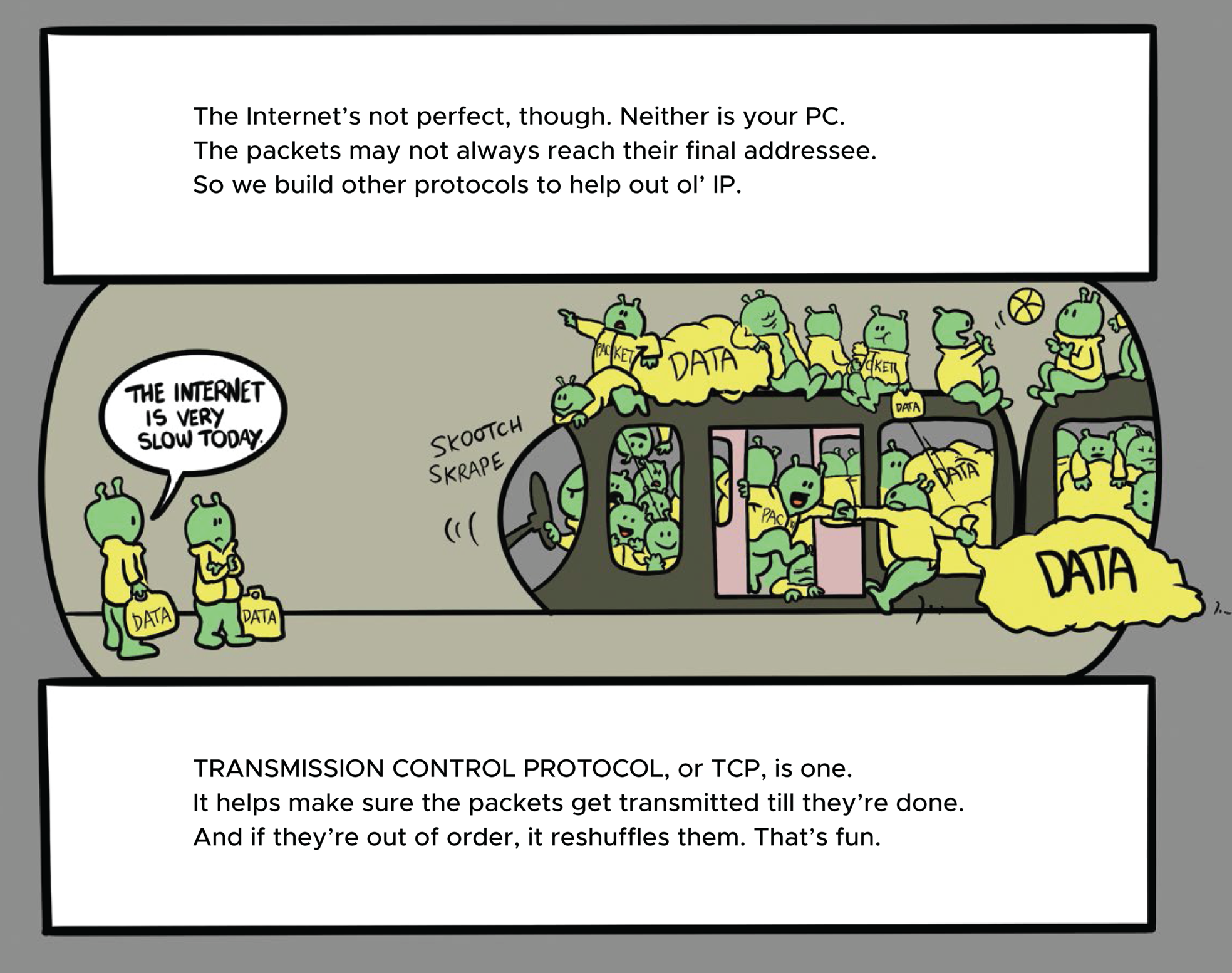

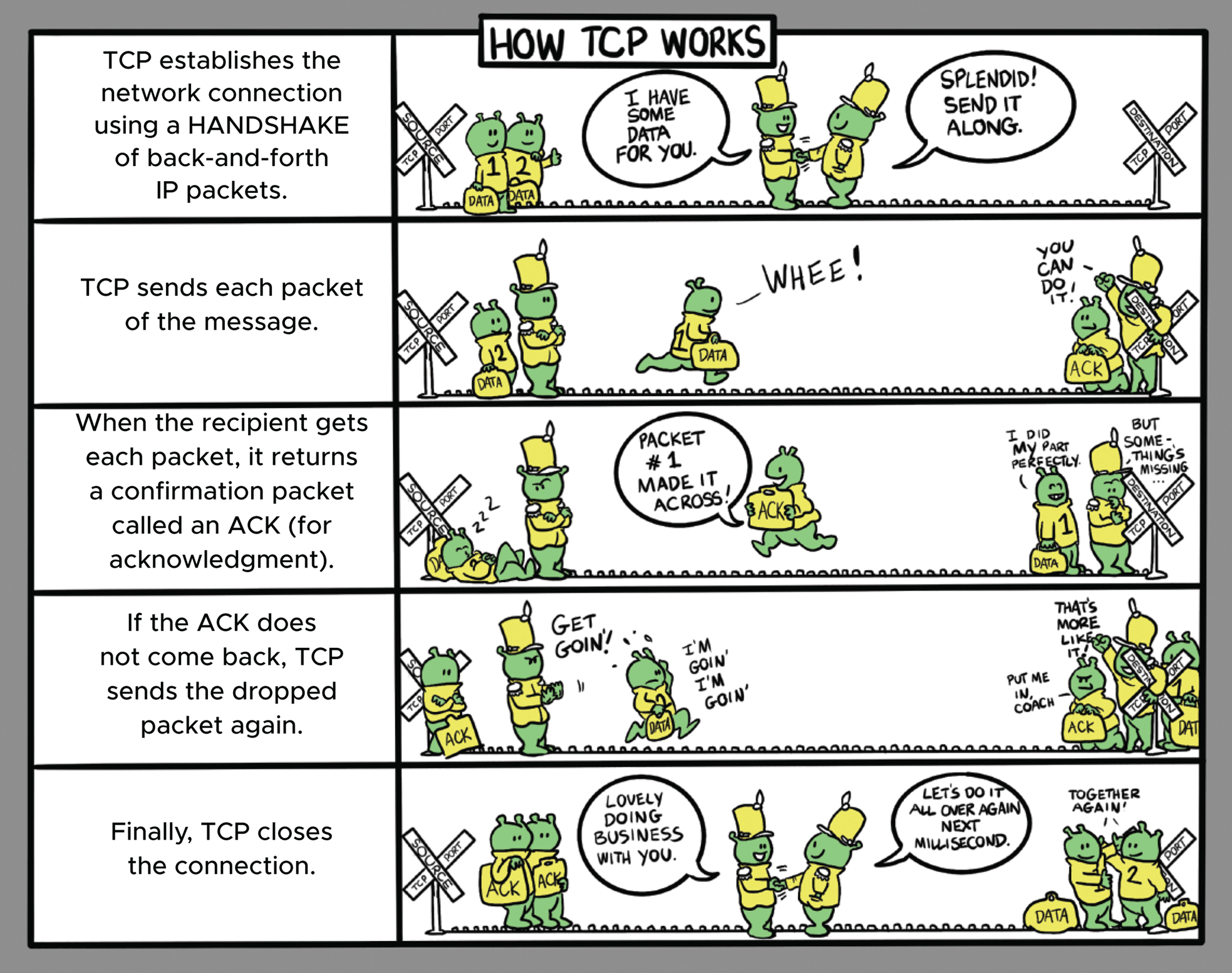

- The transport layer: TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and other higher-level protocols that govern how IP packets are sent and received. These protocols answer questions like, can I guarantee that the packets making up this message will arrive in order? If a packet dies in transit, will it get re-sent? If IP is the airplane, TCP is air traffic control.

- The application layer: The actual data payloads sent in the packets. This could be bits of streaming video, text for a web page, or anything you can express in ones and zeros. Lots of application-level protocols like HTTP govern the format of this data. But now we're past the realm of the Internet and into the domain of the software at each end.

BGP: How Networks Network

It would be wrong to think of the Internet as a single organism, like a brain, where every node is connected with equal weight. Rather, the Internet is balkanized, made up of many smaller networks that must figure out how to communicate with each other. Your Internet service provider (ISP)—like Comcast or AT&T—runs a mini-internet that forwards data to other ISPs to keep you online.

This process is far from straightforward and quite a bit beyond the scope of this book—it involves fiscal and political calculations, as well as constant vigilance over who to trust. (Imagine if I could convince your routers to send traffic into my evil network, pretending I was a valid destination!) Just know that there is some pretty interesting math called the Border Gateway Protocol involved, and it works way better than you would have any right to expect.

DNS

Finally, a quick word about the Domain Name System (DNS). DNS itself is a web service (some might even say a “cloud service”) that translates the friendly names of websites, like wiley.com, into IP addresses so that your computer can communicate with the remote server to download the web page. If your computer hasn't talked to wiley.com before, it will have to contact the nearest DNS server. That server might need to talk to another server, and so on, up to a small number of authoritative root name servers around the world. The root name servers have the final word on what domain names map to which IP addresses.

If that sounds like a possible weak spot for the ol' nuclear apocalypse, well, you're not entirely wrong. Hackers frequently target root name servers with distributed denial-of-service attacks (see “The Great Cloud Heist (and How to Foil It)” in hopes of seriously damaging the Internet. Thankfully, though, the name servers are pretty resilient by now, and most computers cache the DNS names in case of a temporary outage, so it's probably okay.

The Internet Today

From massive undersea cables to the little modem in your closet, the Internet connects the modern world. It's brought along memes, trolls, Instagram, and a complete revolution of our lives and work.

We barely mentioned the word “cloud” in this chapter, and yet we didn't really have to. Without the Internet, the concept of cloud would be meaningless. You'd be back in the mainframe days, plugging your terminal into the central computer. The Internet puts more than just a world of information at your fingertips: it can turn any laptop into a supercomputer.