CHAPTER 9

How to Uncover Your Right-of-Way

The best way to predict the future is to invent it.

ALAN KAY,

when he was at Xerox PARC

Right-of-way is grounded in the assets, relationships, and investments you have already made to run your current business in your current industry. Reciprocity advantage offers a new way to get value from your underutilized strengths to create a new business.

What underutilized assets do you have? If someone comes to you with an idea for making money with something you aren’t currently monetizing, it is worth a discussion. If the idea is one that complements your business and offers an opportunity to make money in new ways, it is a great lead. If it is an idea that uses your assets to make money that you could make on your own, however, it should just become part of your core business—not a reciprocity advantage.

The biggest missed rights-of-way in the 2000s involved social media. All successful brands and big companies have millions of loyal users, but most of them use only those databases to sell the same customers more of the same product in the same ways. However, such networks of users could be an invaluable right-of-way.

Twitter, for example, hit smack in the middle of CNN’s right-of-way. Twitter now provides a medium for tracking rapidly unfolding crisis events—just the kind of events that CNN is so good at tracking and reporting in great detail. Now, CNN chases Twitter and builds it into its reporting. It is too late for CNN to buy Twitter. CNN should have developed Twitter or it could have bought it early, but now it has to adapt and catch up. CNN missed an important part of its own right-of-way.

Similarly, Tumblr developed in Yahoo’s right-of-way. Yahoo should have developed Tumblr or bought it early. Instead it paid over a billion dollars for the popular social network, and Yahoo’s CEO was forced to say sheepishly, “We won’t screw it up.” That is embarrassing for Yahoo, but so instructive for companies seeking to uncover their own rights-of-way before others do. You don’t want to be in a situation where you are forced to overpay for something that was in your right-of-way in the first place.

The value of existing networks is now becoming clear in the big data disruption of this decade. People are crunching the numbers to discover new insights to sell them new kinds of products, services, or experiences—and in more ways.

The challenge for a company is to embrace the disruptions. TED saw the social revolution and created TEDx. IBM saw burgeoning data and created Smarter Planet. Microsoft relented to the users and made Kinect the new platform for gestural interfaces.

How Do You Find Your Right-of-Way?

Finding your right-of-way will require a deep understanding of your business—beyond day-to-day operations. Rethinking your business will open your management team’s eyes to new possibilities.

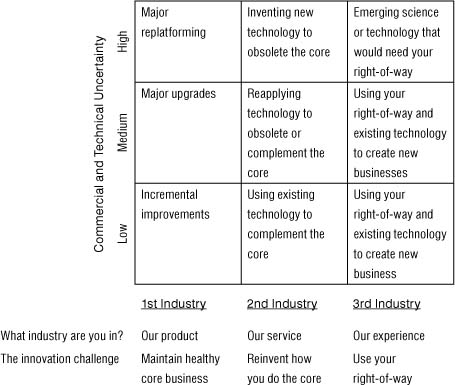

The process we use to help companies has three steps and is done in a workshop format. We involve the senior leaders from the company in a one-day session where they collaborate to do the three-step portfolio assessment process. We force them to map all their projects using the nine-box matrix to assess their innovation portfolios. Essentially we ask them to create their equivalent of the analysis that the railroad companies wished they had made.

The first stage in finding your right-of-way has three parts:

1. Begin by defining your core business. This is where you will find the right-of-way assets you can share. Not all should be shared. You must do this inventory and then decide later what to keep and what to share.

2. Reinvent your business as a service. Stepping back to generalize your business will help you see possible disruptions that could obsolete your core. The rights-of-way that your core needs to survive disruption are not to be shared. This would hurt your business. Instead, invest to prevent long-term obsolescence.

3. Redefine your business as an experience. Having attained clarity on what you do as a service, focus on the users of your service. What are you being hired to do? By looking for services that people want but don’t yet have, you will find new ways to compete that complement, rather than compete with, your core business. The rights-of-way that enable this are the core of the new reciprocity business.

The search is structured to follow specific steps, but the discussion is what matters. Part Three is structured in a workshop style that is designed to start good conversations. Figure 7 is a summary of the process we recommend for uncovering your right-of-way.

FINDING YOUR RIGHT-OF-WAY

Each of your current innovation projects will fall into one of the nine boxes. If a project falls into two boxes, divide it into separate projects. A single project that runs across multiple boxes is not likely to succeed. The team members or their management will be at odds with each other as the project progresses. Divide the project and then choose where to put the priority when you split projects, but don’t allow individual projects to fall across the lines.

Again, the most important part of this exercise will be the discussion. Remember, there will not be just one answer. Create many different maps if you wish. Then get your senior management group together to determine which ones you want to pursue.

Figure 7: Finding Your Right-of-Way.

RIGHT-OF-WAY STEP 1:

AGREE ON YOUR CORE BUSINESS

Do an experiment for yourself. Ask this question of ten people in various parts of your company: “What industry are we in?

Chances are you will get a wide range of answers, from the very specific to the very general. In most companies, there is little clarity around what seems to be such a basic question.

What industry are you in? The objective answer can be found by looking at your sales and profits. What is responsible for two-thirds of your total company’s profits or sales? Ignore the rest of your business when you ask this question. Typically one or two product lines and one or two channels or geographies are your core.

TIPS FOR IDENTIFYING YOUR CURRENT INDUSTRY

These are investments you must make to stay ahead of current competition.

![]() Where do you make two-thirds of your money? This is your core business.

Where do you make two-thirds of your money? This is your core business.

![]() A narrow definition is better than a broad one. This is what you are known for. This is the business you will defend, no matter what.

A narrow definition is better than a broad one. This is what you are known for. This is the business you will defend, no matter what.

![]() Your business is part of a bigger industry. Rules are changed at the industry level. The industry is a global set of competitors with at least $10 billion in annual sales.

Your business is part of a bigger industry. Rules are changed at the industry level. The industry is a global set of competitors with at least $10 billion in annual sales.

![]() Even if you are small, find a set of competitors whose combined sales are in the $10 billion range. You need to know whom you compete against or you will be easily blindsided by competitors moving into your geography.

Even if you are small, find a set of competitors whose combined sales are in the $10 billion range. You need to know whom you compete against or you will be easily blindsided by competitors moving into your geography.

![]() Diversified companies might be in multiple industries. Do this exercise for the whole company to find new enterprise-wide businesses. Then do this exercise for each of the business units in nonaligned industries.

Diversified companies might be in multiple industries. Do this exercise for the whole company to find new enterprise-wide businesses. Then do this exercise for each of the business units in nonaligned industries.

![]() Most innovations are small, but some will require recapitalizing to stay ahead of competition.

Most innovations are small, but some will require recapitalizing to stay ahead of competition.

Don’t worry that the answer to this question will be too narrow. When Karl was in the household cleaning-products business at P&G, they realized they really did only two things: cleaned dishes and floors. Getting really clear on these two businesses allowed them to focus on this core, ignore nonstrategic businesses, and devote efforts to more radical innovations like Swiffer and Febreze.

General Electric (GE) is a huge company. What industry is it in? GE’s core industry is infrastructure. It sells aircraft engines, electric power turbines, large diagnostic medical equipment, diesel engines, nuclear reactors, light bulbs, and appliances. While GE sells light bulbs and appliances to consumers, it is not just a consumer company. Its core is huge business-to-business billion-dollar deals.

The core is where you will find your right-of-way for extending into new businesses. And the core will still take the majority of your innovation budget to continuously produce the incremental innovations necessary to stay ahead of competition and to fill all market segments. Keep making your core business better and better. Keep investing in the new technologies to keep ahead of competition. Grow your market share and profitability. Run the best company in your industry.

There’s also a practical reason why we start with getting firm agreement on the core business. Without a sound innovation plan for the core business, you will chase the competition and stop all new business efforts when a new product enters the market. New business is not necessarily harder than your existing business, but it must be nurtured with continued support. And you can’t nurture new business if you’re putting out daily fires in your current business. So fix the core first.

RIGHT-OF-WAY STEP 2:

REINVENT YOUR BUSINESS AS A SERVICE

Ted Levitt, in the landmark Harvard Business Review article “Marketing Myopia,” observed that the train companies were not just in the train industry—they also were in the transportation industry.42 His article inspired our railroad model example.

Besides writing in the article about trains, Levitt pointed to electric drills. Why do people use a drill? The answer: they need to make a hole. People who make drills are in the business of making holes. Christensen calls this the “job to be done.” Or more commonly, he asks, what job are you being hired to do?

TIPS FOR IDENTIFYING YOUR SERVICE INDUSTRY

These are investments you must make to prevent your core business from being obsoleted by new competitors.

![]() What do people hire you to do? Anyone who can do this is a direct competitor.

What do people hire you to do? Anyone who can do this is a direct competitor.

![]() Any way that serves your current customers that is orders of magnitude better and cheaper will obsolete your core business over time.

Any way that serves your current customers that is orders of magnitude better and cheaper will obsolete your core business over time.

![]() First versions of the disruption will be crude. Your love of your assets will make you slow to respond.

First versions of the disruption will be crude. Your love of your assets will make you slow to respond.

![]() Obsolete yourself before others do.

Obsolete yourself before others do.

![]() If you miss the early disruptions, you will have to acquire the companies.

If you miss the early disruptions, you will have to acquire the companies.

If the first business is drilling holes, the second business is selling anything that makes a hole—even if it requires no drill. We refer to the second industry as a service because it involves hiring you to do the same job you do today but doesn’t necessarily use your assets.

Once you have defined your core industry, step back and ask this question: what do people hire us to do?

Forget how you do what you do. Rather, focus on the end result, or the benefit. See the hole—not the drill. Any business that can do what you do—and do it better, faster, or at half the cost—will eventually disrupt you. The good news is that it typically takes ten to twenty years before you become obsolete. Digital will disrupt physical. Smart phone apps have already disrupted single-use devices such as cameras and teleconferencing systems. Why? The incremental cost of a digital transaction is minimal versus the same transaction physically.

The investment in the second industry is complementary to the current investment in the core. Thus, while most of your innovation budget will be spent on the core, about 15 percent of the total innovation investment must be held aside to prevent being obsoleted. You must accomplish this goal for the long run, and it will not be cheap to do. Lead the transition or be run over by it. The railroad companies also needed to get into the airline, trucking, and container-ship businesses because any way that bulk goods or masses of people were moved should have been their kind of business.

It is not optional to get into these service businesses. If there is a business that does what you do a great deal faster or more cheaply, it will eventually be the dominant way of doing business. Rather, you need to make multiple investments in emerging industries that do what you do in radically different ways. This needs to be isolated from the 80 percent of the money that is spent supporting the core, or it will get stolen for short-term fires. As an executive at one company told Karl, “Beware the giant sucking sound of the core.”

You will need to keep improving your core business while alternate innovative forms mature. Kodak needed to continue to support silver film for decades, while at the same time it created a new digital business. Over time, the balance of spending will shift toward the disruption, but not for many years. That shift can be difficult, though. Kodak saw the future but never could embrace it. Just as railroad companies loved their trains too much, Kodak loved its silver chemistry too much.

RIGHT-OF-WAY STEP 3:

REDEFINE YOUR BUSINESS AS AN EXPERIENCE

In 1999 Joe Pine was writing about a disruption in how we think about economics and value creation. Pine and his coauthor Jim Gilmore wrote The Experience Economy: Work Is Theater and Every Business a Stage. They argued there is a natural progression from products to services to experiences. This perspective was not embraced when the book first came out, but the truth of the argument is now increasingly obvious.

So once you have defined your core business and your service industry, ask yourself: if my business were an experience, what industry would I be in?

TIPS FOR IDENTIFYING YOUR EXPERIENCE

These investments create totally incremental, profitable growth made possible by new uses of your existing right-of-way.

![]() When aren’t your desired customers hiring you? Consider all times, for all people.

When aren’t your desired customers hiring you? Consider all times, for all people.

![]() Focus on nonconsumption; ignore current consumption patterns of your core business. This new business will occur at other times, complementing current consumption patterns.

Focus on nonconsumption; ignore current consumption patterns of your core business. This new business will occur at other times, complementing current consumption patterns.

![]() Enable people to experience your product’s benefits when it is currently impossible to use them.

Enable people to experience your product’s benefits when it is currently impossible to use them.

![]() Democratize existing desired products and services by substantially reducing the price to meet these needs.

Democratize existing desired products and services by substantially reducing the price to meet these needs.

How often do you get on a train or plane? How many personal business letters do you get through the physical mail? Even if the train companies had invested in planes and trucks, they would have missed the biggest change in the twentieth century—the information and communications revolution.

Imagine a person who lives on the East Coast who has a cousin who lives on the West Coast. At the height of railroad travel, these cousins might have taken the train to visit each other. But because the trip was very long, they rarely saw each other. Commercial airlines shrank the amount of time it took to travel. Planes are the faster version of trains and thus obsoleted railroads as a method to visit distant relatives.

To find this third industry, you need to ask these two cousins what experience they were seeking when they decided to take the train. What did they want to do that caused them to travel? They just wanted to keep in touch. This is what Pine and Gilmore understood—that communication consists of sending words but doesn’t necessarily require spending days crossing the country via train.

If you are in the business of moving people, you will argue quite quickly that nothing beats being there in person. It is this kind of logic that most quickly kills new businesses. It is a false dilemma. If you can travel, do so. If you can’t travel, then the relevant benchmark is better than doing nothing. Christensen calls this competing against nonconsumption. Something beats nothing most of the time. Only rarely does a new medium replace an old one. Rather, the new medium tends to disrupt the way we use existing media—and those media blend with each other.

Kodak sold cheap cameras at Disneyland because the quality of the picture from your expensive Nikon camera was irrelevant if you forgot to bring it. Blackberry was a very poor machine for doing multipage documents but brilliant for a three-sentence note to get work done before you got back to the office.

The goal of these new-experience businesses is to augment the sales by getting people to pay for things they are not currently buying. Whereas the investments in your new service industries may obsolete your current products, these experience businesses create new markets. So while the new businesses start small, they are nearly 100 percent incremental and can mature into businesses that are much larger than your current company.

Historic Right-of-Way Lessons from the Railroads

Our goal of the three-step process to understanding your business is to help you find the right-of-way that you can share via partnering to create new sources of growth. This is about creating your future. However, a glimpse of the past can help make this more concrete. So, let’s now look in detail at how the train business might have evolved.

We know the outcome: the train companies were disrupted by the telegraph. The telegraph enabled the train companies to know exactly where their trains were at any point in time., which allowed them to improve their existing service and to lower the cost. The accounting departments were probably ecstatic because they used the new technology to improve the current business. But they missed the communication revolution, even though they owned the right-of-way for it.

The train companies failed to see that the air rights over their tracks was an asset, so they lost the opportunity to develop telegraphy. Their underutilized asset was the air over their tracks, which was doing nothing for anyone and they were making no money from it. It was there, but they didn’t see its potential. When the telegraph people first approached them, the railroad companies should have said something like this: “Tell us more about what you want to do.” If the railroads had seen the potential in that asset, they could have had a valuable pathway to growth.

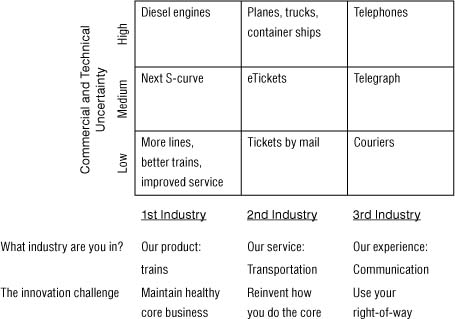

Figure 8 is an example of what the ideal (prescient!) innovation portfolio would have looked like for the railroads industry. The portfolio is a 3-by-3 matrix of innovation investments. Each project a company does will fall into one of the nine boxes. We’ve filled out the matrix we introduced earlier in this chapter to help you find your own right-of-way, but we’ve filled it in the way the railroads wish they might have done it.

THE INNOVATION PORTFOLIO THE RAILROADS NEEDED

The first column shows the existing train business, the core business. The second column represents the broader definition of the industry within which the core business exists—transportation, or the job trains do. The final column presents potential reciprocity businesses that use an existing right-of-way—communications. Remember that understanding your existing business is necessary to uncovering your right-of-way.

Figure 8 reveals three businesses—not just one. In this case, trains represent the core business, but this matrix also shows how investing in diesel engines is a necessary step to stay ahead of competition, though it isn’t sufficient. New technologies are reinventing the ways people travel. These investments in reinvention will complement the core business but still involve moving people and things from place to place.

Figure 8: The Innovation Portfolio the Railroads Needed.

The second problem the railroads faced was the emergence of airplanes and trucks, which moved people and freight en masse. When these technologies achieved maturity, they posed a direct threat to the railroads’ core business. Given the funding required to re-platform and buy those diesel engines, we can only imagine the conversation that occurred, but it probably went something like this: “Strategy is about choices. We have to buy these new engines to beat our competitors. Planes are impractical and trucks are unreliable.” The railroads were caught in their present reality and failed to hold aside separate innovation money to create the future.

The biggest insight from Figure 8 is that the third business for railroads could have been communications, allowing people to meet without requiring travel. With hindsight, this is easy to spot as a huge missed opportunity. The emerging technologies that would have allowed this to happen a century ago were the telegraph and, later, the telephone. The railroads had the right-of-way needed to facilitate the growth of communications, but they didn’t see the potential.

As the move to a broader transportation industry occurred, all types of transportation would still need to sell trips to people and track all the things they were moving. What changed is that the new technology involved planes and trucks. The railroads maintained the rights-of-way that helped them run their trains behind the scenes, but in order to imagine themselves in the telecommunications business, they would have had to stop requiring that their customers physically board a train.

The initial move from trains to the broader definition of transportation would have been extremely expensive. They would have had to invest in new planes and airport terminals or trucks and new distribution centers. The sheer magnitude of the investment would have made it very risky, but ultimately every company must make this transition or sit on the sidelines as they become obsolete.

Smart investing can help you transition from your first industry to your second. But if you miss it, you must buy it. When e-commerce was created, it was not a matter of bricks or clicks—it was bricks and clicks. Amazon didn’t have to win; retailers let them in by dismissing the importance of something that could do what they were doing with thousands of times the inventory at marginal costs that were minimal.

The right-of-way the railroads had was their literal right-of-way, the land under their tracks. Letting wires run above their tracks made it possible to communicate information. But goods still needed to be shipped and people still needed to travel. Allowing access to this right-of-way didn’t meaningfully threaten the core business. To find this kind of right-of-way, you have to have an insight into the nature of your business that is more profound. Think about the experience behind your business.

People need to communicate, and if it is instant, they will do it ten times more frequently. You can’t be on three continents in one morning, but you can make three calls. This is a huge opportunity, but nobody can do it alone. The communication business is nothing like transportation. They needed partners and the right-of-way to the railroads’ land.

If you look back at the railroad portfolio matrix, you will also notice smaller business opportunities. Once you identify the new business area, look at the many low- to high-risk ways of evaluating new markets. Courier services were a very low-risk way to approach the market. Telegraphs presented a medium risk, and telephones were the riskiest of the three. The railroads needed to experiment in all these areas to create their future.

In summary, when you do apply this three-step analysis process to your own business, multiple answers will emerge. Encourage debate and create numerous maps of your future. Converge too quickly, and you might miss tremendous opportunities. Once you’ve uncovered your underutilized right-of-way, the next step will be searching for a partner that will enable you to accomplish what you cannot do alone.