Postscript: How to Care for the Broken and the Depressed

It would be easier for me to discuss my mental health issues if it was not such a charged topic … if my friends did not try to address my depression themselves.

– Founder, United States

Researchers believe that the inability of the depressed to respond to offers of help is one of the most aversive qualities of depression. Just as workers will not end a strike until their employer offers a significant increase in salary, most initial offers of help do not lead to recovery from depression. The depressed have serious problems and the initial offers of help are “too small” to solve them. The depressed need to compel substantially better offers from reluctant social partners.

– Edward Hagen and Kristen Syme, University of Washington1

In the past we locked the depressed up in distant places like hospitals and sanitariums. We even used electric shocks. We hide them, ignore them, or make them go away. Maybe because we are not equipped to talk about these topics.

At home, we try to fix the problem ourselves. We rush in to help friends and family members but have no tools. Our fear, helplessness, and panic set in. Our own discomfort creates a bigger problem. We try to avoid both – our discomfort as well as the depressed person. As we are unable to handle our own inner states, we run away from the ones who are depressed. We have neither the right language nor the tools, but this is a start.

TOP REASONS FOUNDERS DO NOT ASK

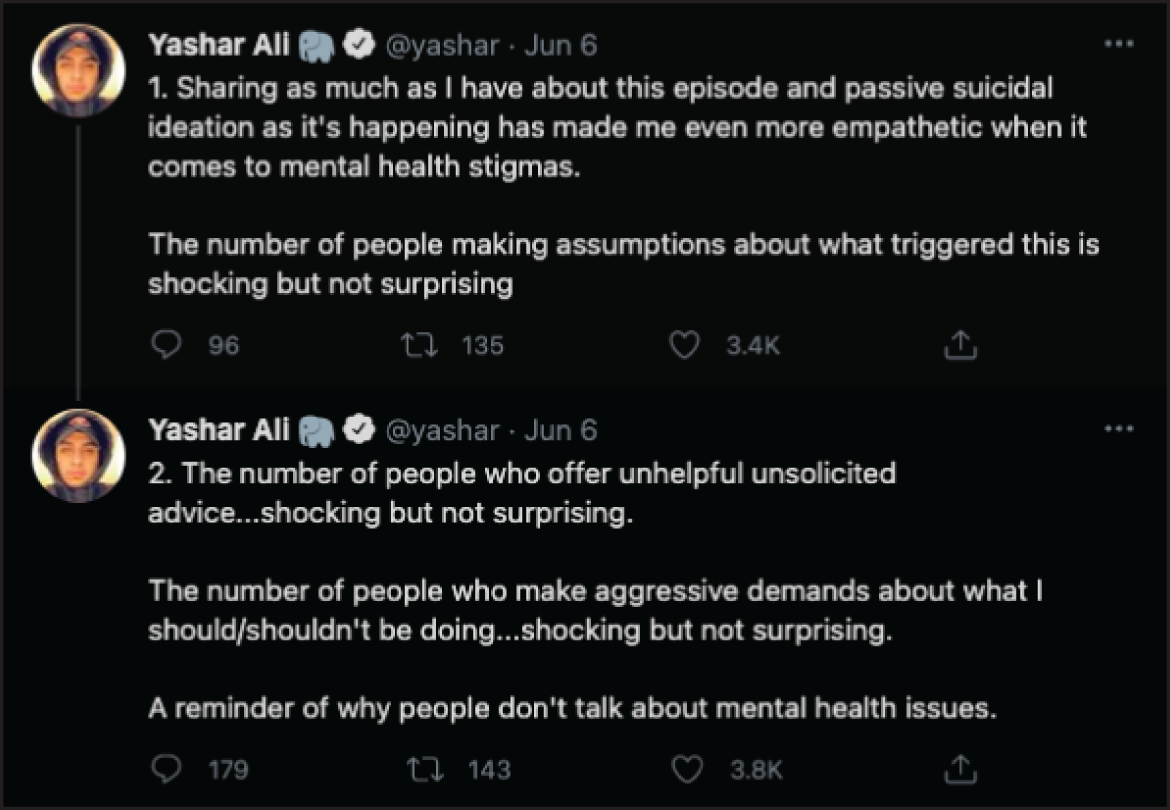

Social media is rife with tweets about reaching out and asking for help. But we don't really want to talk about it. Fear of judgment and stigma is real. And most people cannot handle it or are poor listeners.

Researchers state that depressed people have a distinctive style of communication that is effective at expressing sadness and despair but not other emotions. Their conversations signal that they have problems. They want to talk about them and gain reassurance and support.2 Founders struggling with depression shared the top reasons they do not reach out or ask for help:

Fear and Repercussions

- Fear of judgment and stigma. “I feel broken,” writes one founder.

- Fear and shame of being perceived as weak or incapable … admission of failure. My investors did not take me seriously when I tried to share my mental health challenges. As a society, we are obsessed with proving how strong we are and with outlandish displays of strength. There are times when I don't think I can handle the pressure.

- Fear of being marginalized at work. “Speaking about this at work or discussing this with investors is a career-limiting move.”

- Fear of being taken advantage of.

- Fear of scaring people away, or losing respect.

Sympathy and Pity

- I don't want pity or false assurances.

- I don't want people to treat me differently.

- As female CEOs, we are often stereotyped as being weak. I cannot feed this stereotype by sharing my condition.

Sense of Responsibility

- I should not be dumping on or spreading my gloom/making others sad with my baggage.

- People don't want to hear your negative stuff and want to be around positive people so I mostly keep quiet.

- The last person anyone is worried about is the CEO. It is really lonely in my role.

Source: Twitter, Inc.

WHAT DO THE DEPRESSED NEED?

“I just need someone to hold my hand and say some simple comforting words like ‘I too would feel stressed – I know building a company is scary,’ ” writes one founder. Another founder said that empathy comes from knowing the pain. “The only people who seem to understand are the ones who have been through it, which is why we have built a small CEO support group.” But not everyone may have the luxury of having like-minded CEOs in their network or region.

Founders tell us what they need:

- We need the same friendships and support and care, just like any other human being.

- Simple and “mild” check-ins. A call or text to see how I'm doing. A walk in the evening or a meal.

- Safe environments - authentic/honest engagement – no judgments or extreme reactions, without trying to solve my problems. Also, don’t give advice. Just empathize.

- Listening nonjudgmentally, be comfortable in silence, hold the space, and give me space if I need it.

- Just love me as I am. Let me know that I'm loved. No need for you to try and be perfect in your effort.

- Get educated on depression. We don't even have a vocabulary for how to deal with sadness, or how to act when others around us are sad. How can we teach this to our children?

WHEN YOU MEET SOMEONE DEEP IN GRIEF

Slip off your needs

and set them by the door.

Enter barefoot

this darkened chapel

hollowed by loss

hallowed by sorrow

its gray stone walls

and floor.

You, congregation

of one

are here to listen

not to sing.

Kneel in the back pew.

Make no sound,

let the candles

speak.

Patricia McKernon Runkle

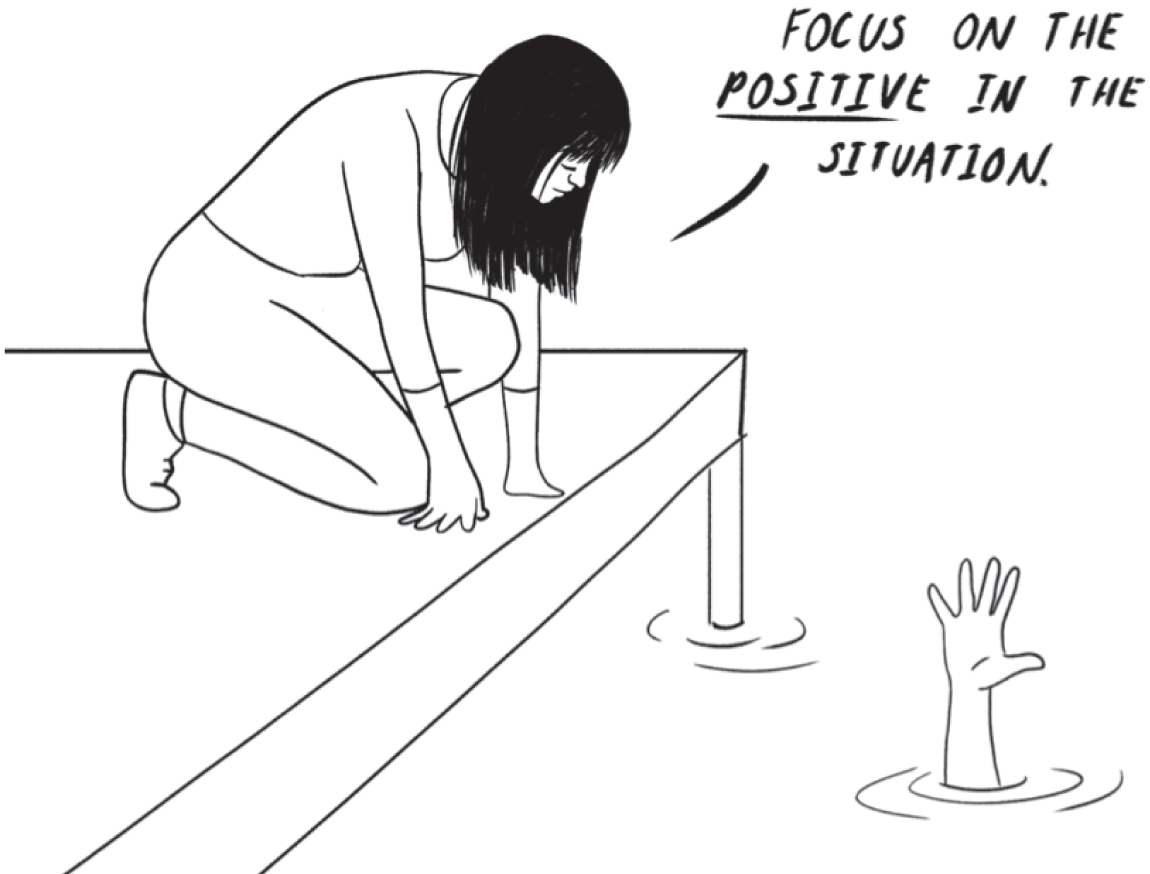

On a rare occasion, when we have an opportunity to help others or offer advice, it can be extremely seductive. We feel important. We often gladly give advice without fully appreciating the fact that we may not be qualified to do so, or our that perspectives may be colored or flawed in their own way. Each one may have different thresholds of motivation, confidence, willpower, and perseverance.

WHAT THE DEPRESSED DO NOT NEED

Founders unequivocally share what they do NOT need:

- Stop cheering me on. Saying stuff like “You are a star and you will shine” – it only worsens my mood and adds pressure.

- Don't try to get me out of my mood. I cannot turn off sad feelings – there is no kill switch. I did not hire you as my cheerleader, did I?

- Once you know about it, let me be the one to bring up the topic and anything about my mental health and depression. I don't want advice, just acknowledgment.

- Try not to start our conversation every time with “So how have you been feeling?” or say things like “You can do it” or “Keep trying – you will get out of it.” Many try to build me up as a “can-do” hero, which does not help.

- I am not looking for any special treatment. My being depressed doesn't mean I am unable to have a normal conversation about weather, funny incidents, and life in general.

- Don't tell me your own stories: I know you may be trying to empathize by saying it happens to everyone but stop telling me your own stories and hijacking the conversation. I am trying to express my feelings and you jumping in with your own stories is being insensitive or even incredibly unaware and selfish.

- Curb your discomfort, anger, and sarcasm:. “When my partner made a joke out of it when I shared my mental health challenges, I knew I had to ask for help elsewhere. This made me even more sad,” writes one founder. My spouse jumps at me, screaming, “Are you depressed again?” when I am having a bad day. They are afraid or worried that I might become a bigger liability for them.

- No advice or unsolicited inquiries.

HOW TO HELP – A FEW GOOD EXAMPLES

Some deeply touching ways to respectfully support someone as they go through this journey can be seen from these examples.

Carl Jung, in a letter to a friend, warns against half-hearted measures:

In this letter, Jung points out the importance of seeking a few people out, maybe moving to another country – a change of scenery. But the inner work required to acknowledge that the dark angel is also the light and the blue sky, which depression withholds – these are sheer gems of wisdom. Whatever we do, Jung says, do it with every fiber of our soul.

In another example, singer and songwriter Jewel wrote a letter to Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos, in which she prescribes the company of right people. “I am going to be blunt, I need to tell you that I don't think you are well and in your right mind. I think you are taking too many drugs that cause you to disassociate … The people you are surrounding yourself with are either ignorant or willing to be complicit in you killing yourself.”

It's Only Darkness, Not the End

Author Henry James shares his own helplessness as he offers authentic advice to friend and author Grace Norton. Henry, who had his own bouts of depression, avoids offering precise solutions to Grace. As we read his letter, his compassion and deep wisdom shine through.

My dear Grace,

Before the sufferings of others I am always utterly powerless, and the letter you gave me reveals such depths of suffering that I hardly know what to say to you. This indeed is not my last word – but it must be my first. You are not isolated, verily, in such states of feeling as this – that is, in the sense that you appear to make all the misery of all mankind your own; only I have a terrible sense that you give all and receive nothing – that there is no reciprocity in your sympathy – that you have all the affliction of it and none of the returns. However – I am determined not to speak to you except with the voice of stoicism.

I don't know why we live – the gift of life comes to us from I don't know what source or for what purpose; but I believe we can go on living for the reason that (always of course up to a certain point) life is the most valuable thing we know anything about and it is therefore presumptively a great mistake to surrender it while there is any yet left in the cup. In other words consciousness is an illimitable power, and though at times it may seem to be all consciousness of misery, yet in the way it propagates itself from wave to wave, so that we never cease to feel, though at moments we appear to, try to, pray to, there is something that holds one in one's place, makes it a standpoint in the universe which it is probably good not to forsake. You are right in your consciousness that we are all echoes and reverberations of the same, and you are noble when your interest and pity as to everything that surrounds you, appears to have a sustaining and harmonizing power. Only don't, I beseech you, generalize too much in these sympathies and tendernesses – remember that every life is a special problem which is not yours but another's, and content yourself with the terrible algebra of your own. Don't melt too much into the universe, but be as solid and dense and fixed as you can. We all live together, and those of us who love and know, live so most. We help each other – even unconsciously, each in our own effort, we lighten the effort of others, we contribute to the sum of success, make it possible for others to live. Sorrow comes in great waves – no one can know that better than you – but it rolls over us, and though it may almost smother us it leaves us on the spot and we know that if it is strong we are stronger, inasmuch as it passes and we remain. It wears us, uses us, but we wear it and use it in return; and it is blind, whereas we after a manner see.

My dear Grace, you are passing through a darkness in which I myself in my ignorance see nothing but that you have been made wretchedly ill by it; but it is only a darkness, it is not an end, or the end. Don't think, don't feel, any more than you can help, don't conclude or decide—don't do anything but wait. Everything will pass, and serenity and accepted mysteries and disillusionments, and the tenderness of a few good people, and new opportunities and ever so much of life, in a word, will remain. You will do all sorts of things yet, and I will help you. The only thing is not to melt in the meanwhile. I insist upon the necessity of a sort of mechanical condensation – so that however fast the horse may run away there will, when he pulls up, be a somewhat agitated but perfectly identical G. N. left in the saddle. Try not to be ill – that is all; for in that there is a future. You are marked out for success, and you must not fail. You have my tenderest affection and all my confidence.

Ever your faithful friend—

Henry James,

July 1883

Reading Poetry Aloud

In previous sections of this book, we covered the joy of reading poetry, possibly to help our own selves. But reading poetry to a friend who may be down can be therapeutic, calming, and caring in so many ways. Before you head over with a fat volume of Whitman, Rupi Kaur, or Emily Dickinson, do make sure that poetry is their thing – that they care about and like poems – else you run the risk of exacerbating their pain, all the while thinking you are really helping them.

In this touching example of caring for the broken, Phillip Moffitt, former president of Esquire magazine, writes about David, his dear friend who stood by him in his darkest hour. When Phillip sold the publishing company, he went through a deeply troubling time – call it depression, or being lost in the woods. In such moments of despair, one of his friends flew to New York and spent the weekend with Phillip. “When I was struggling with my emotional chaos, David flew to New York and spent a weekend reading T.S. Eliot's “Little Gidding” from Four Quartets out loud to me. It was the first time I realized the deep wisdom with which Eliot addressed the modern dilemma of suffering, and Eliot's words continued to be of great comfort to me during that difficult period.”

Wait, what? Two men. Reading poetry. Out loud! WTF are these dudes doing?

But once we look beneath the surface, “Little Gidding” is a pretty amazing poem.

The poem is very long (no wonder it took a whole weekend to read it) but touches, in very subtle ways, how time heals everything, how all shall be well, and how patience is key.

And that the fires within purify us so that we can become like a rose.

Reading poems to strangers as they walk by – San Francisco

Let’s Make Stories Together

When a founder’s close friend was struggling with depression, she used a gentle yet creative way to help him through the dark nights:

Massaging the Soles of Your Feet

And then there is the mother of all examples – unheard of and unparalleled in its level of care: massaging the feet of a depressed friend.

Parker Palmer, an author and educator who was supported by his friend amidst his depression writes,

In hearing such narratives, we have to admire the sensitivity, awareness, and bonds that exist between such friends – where one of them knows the other well enough to offer – feels comfortable massaging the soles of the other's feet – and the other is equally comfortable receiving this gift with grace.

It takes two to tango. The receiver as well as the giver must dance to the same beat. If you don't know someone really well, showing up at their door and offering to massage their feet may positively spook them out.

Good intentions have to be anchored and centered around their needs, not what we want to do to feel good about ourselves.

Approach the Depressed with Care

Approach the depressed as you would approach a wounded animal, a deer or a gentle rabbit, hiding in the forest, trying to recuperate. Approach very slowly. Build trust.

And let them show where the wounds are. To care for the depressed is not easy – for they are hiding in their shell most of the time.

In building the core of trust with another, we can write our own code of conduct:

- Reliable – I am reliable and I am here when you need to speak with me.

- Steady – Your situation does not cause me to panic or be afraid. It invokes the caring side of me.

- Support and Servitude – I am here to serve. This is about what you need, not what I think you should do. I have no agenda but to make sure you become resilient.

- Responsibility – I know the limits of what I can do and what I cannot do. I know when we may need to ask for professional help. I am not trying to be your one-stop shop, monopoly emotional store, nor am I playing God, but being a companion.

- Trust – I do not judge you, discuss your situation with anyone, criticize, or gossip.

- Detachment – I do not have preconceived notions of your progress, recovery, or outcomes. I am here to have a conversation and just be by your side. If you do not reciprocate, I will have no hard feelings.

Basket Of Figs

-by Ellen Bass

Bring me your pain, love. Spread

it out like fine rugs, silk sashes,

warm eggs, cinnamon

and cloves in burlap sacks. Show me

the detail, the intricate embroidery

on the collar, tiny shell buttons,

the hem stitched the way you were taught,

pricking just a thread, almost invisible.

Unclasp it like jewels, the gold

still hot from your body. Empty

your basket of figs. Spill your wine.

That hard nugget of pain, I would suck it,

cradling it on my tongue like the slick

seed of pomegranate. I would lift it

tenderly, as a great animal might

carry a small one in the private

cave of the mouth