p.447

Theoretical issues in management ethics

Joseph A. Petrick

Within the field of management ethics, one finds at least two broad types of theories: theories of management and theories of ethics. For the management ethicist, these theories may intersect or be used independently of one another. For the practicing manager, these theories may have an explicit or tacit influence. For example, a manager of a pharmaceutical firm may implement an advertising strategy in a developing country whose effect will be to encourage unsuspecting consumers to medicate with drugs that are outlawed in more economically prosperous nations. This type of action could be based on the assumption that such a strategy is justified because it promises an increase in short-term profit. Indeed, this manager might seek to defend this initiative on the basis of either a management theory or a particular theory of ethical action (or both). Whether explicit or implicit, theoretical assumptions are often embedded in managerial moral performance; it is, therefore, critical for both practicing managers and management theorists to understand these theoretical assumptions if managerial performance is to be both productive and ethical.

On the assumption that increased awareness of and engagement with alternative management and ethics theories can lead to more responsible managerial decisions and improved moral performance, this chapter offers a broad overview of such theories. The first section of the chapter summarizes, schematically, several of the outstanding theories of management. The second section draws some distinctions between various theories of normative ethics. The third section addresses two topics at the theoretical intersection of management and ethics: moral monism versus moral pluralism, and the degree to which management conduct (or conduct more generally) is guided by considerations of rationalized theories.

According to most major management theorists optimal business management entails effectiveness (competing to achieve goals fast), efficiency (controlling to do things right and not waste resources in the process), innovation (creating new products and techniques, continually improving outputs and processes), responsiveness (collaborating to do things together to address multiple stakeholder interests), sound decision-making (relying on evidence-based judgments), and the avoidance of harm or exploitation (critically evaluating management practices). Suboptimal business management performance occurs when managers neglect or inadequately operationalize some or all of the above expectations. To explain (and to guide) these features of optimal management, writers and scholars have articulated theories of optimal business management practice (Quinn et al. 2015). Most of these theories operate at both a descriptive and normative level: in other words, the theories not only explain certain features of management practice but encourage specific emphases as essential to moral and business success. In the following discussion, these theories are schematically summarized, noting salient strengths and limitations.

p.448

The rational goal theory of management stresses the importance of performance effectiveness, as achievable through setting goals, speeding productivity, and increasing profits faster than external competitors. To realize these measures, the manager may use time-and-motion studies, financial incentives, or technological power to maximize output (Taylor 1911). The strength of this theory is that it accounts for managers providing structure to the activities of the firm and it emphasizes the significance of management initiative and leadership. Such a theory can be misused if it imposes demands on employees that cannot be sustained. The theory may allow or encourage a neglect of individual psychosocial needs in the pursuit of economic returns, thereby affecting individuals negatively and destroying the cohesion necessary to attain the desired goals.

The internal process theory of management stresses the importance of operational efficiency as achieved through information management, documentation control, and coordinated processes. Such a theory emphasizes process measurement, the smooth functioning of organizational operations, and the maintenance of structural order. Henri Fayol (1916), the earliest originator of this type of theory, described the five functions of management as planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling, and he outlined fourteen principles of good administration, with the most important elements being specialization of labor, unity and chain of command, and the routine exercise of authority to ensure internal control. The strength of this theory is that it accounts for managers’ maintaining structure and collecting information. A cautionary note would point out that an exclusive emphasis on processes and structures may neglect new products and techniques, thereby stifling overall progress.

The human relations theory of management stresses the importance of stakeholder responsiveness achieved by showing managerial consideration for employees’ psychosocial needs to belong, fostering informal group collaboration, and providing recognition at work. This theory also encourages managerial social responsibility and humane community building in society (Mayo 1933). The particular strength of this theory is its encouragement of managerial and employee relationships, as well as the importance of managerial leadership to sustain supportive interaction with stakeholders beyond the firm. Of course, to the extent that a manager becomes concerned only with the development of human relationships, then so does that manager create the risk of slowing production at work and abdicating decision-making authority.

The open systems theory of management stresses the importance of sustainable innovation. Positive changes are to be achieved by cultivating organizational learning cultures, developing cross-functional organizational competencies, and respecting quality and ecological system limits (while negotiating for external resource acquisition), building sustainable entrepreneurial networks, and enabling creative system improvement (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967). One positive feature of this theory is that it accounts for managers envisioning improvements and acquiring resources for sustainable system development. However, the implementation of the theory may risk a disruption of established operational procedures and may lead to projects of innovation that do not succeed.

The evidence-based theory of management (EBM) contends that managerial decisions and organizational practices be informed by the best available scientific evidence. The theory focuses, therefore, on fact gathering, examining issues from multiple perspectives, analyzing cause–effect connections, and utilizing communities of knowledge—activities essential to arriving at effective management decisions or policies (Rousseau 2014). Evidence-based management assumes that the integration of scientific analysis with critical reasoning enhances both management education and management performance, as it has done for medical education and medical performance. The strength of this theory is that a science-based practice of management not only encourages in the manager an attitude of serious and realistic assessment, but it also promises to deliver better outcomes now and in the future by promoting knowledge-building relationships among management scholars, educators and practitioners. One challenge for this theory is that managers may find that there is no easy access to current aggregated, evaluated, and applicable research that could be employed to improve managerial performance.

p.449

Critical management studies (CMS) is less a discrete and univocal theory of management than it is a neo-Marxist critique of traditional management theory and practice and its accommodation to capitalist societies or its seeming legitimization of exploitative business practices. This neo-Marxist critique is pursued by left-wing scholars informed by a variety of theoretical orientations, “including anarchism, critical theory, feminism, Marxism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, postcolonialism and psychoanalysis, representing a pluralistic, multidisciplinary field” (www.criticalmanagement.org/content/about-cms). The aim of CMS is to radically decrease the socio-economic domination of capitalism by critiquing existing relations of power and control and by proposing alternative non-capitalist forms of organizing work and life, thereby liberating human beings from class, racial, and gender discrimination (Alvesson et al. 2011). A theoretical orientation such as this provides a robust challenge to traditional business practice, and such a perspective may prove salutary even if it is not accepted. The viability of constructive yet non-capitalist forms of production remains less than clear, however. And the appeal to various forms of domination are often more assumed than explained or justified.

These theories of management exist alongside another kind of theory, a theory of fiduciary responsibility: Does a manager (or a corporate board) have a primary fiduciary responsibility to stockholders or to stakeholders? Some consider Milton Friedman (1962, 1970) to be advocating the shareholder view but, whatever the case, the shareholder perspective does not entail that a manager has no duties except to the shareholder (Norman 2013), only that the manager (or the corporate board) has a fiduciary duty to manage the firm in the interests of shareholders. The stakeholder paradigm suggests, in various guises, that management should run the firm with a respect or concern for the interests and views of multiple constituencies such as employees, investors, customers, suppliers, creditors and the public at large (Freeman et al. 2007; Ghoshal 2005).

In principle, each of the above theories of management is compatible with either shareholder or stakeholder responsibility. Some of these theories do suggest that the manager bears responsibilities to stakeholders but that suggestion need not entail that a manager or a board has any fiduciary responsibility to these stakeholders, or a duty that is either equivalent or similar to the responsibility to shareholders. Across almost all of the theories sketched previously, it could be said that a manager may bear special formal and informal contractual relationships as agents to a principal (such as a shareholder), or as stakeholder trustees or as property stewards or as employee supervisors; these relationships may entail additional moral and legal contractual obligations (Mitnick 2008). These contractual relationships differ in terms of their prioritized responsibilities: for example, to advance the interests of the principal or stockholders, to advance the aggregate interests of all stakeholders, to protect and maintain property, or to use supervisory authority to facilitate mutually beneficial cooperation among employees. As an agent of a principal/owner, a manager has the duties to act on behalf of the interests of the principal/owner, to obey the reasonable directions of the principal/owner, and never to act contrary to the interests of the principal/owner. At times, however, when a manager as an agent has more expertise in a specific area than the principal/owner, he is prohibited by his professional ethics to exploit his informational asymmetry advantage and may abridge the normal agency duty to obey the principal/owner if in his professional judgment the principal/owner is about to do something extremely foolish against his (the principal/owner’s) interests. On the other hand, a manager who counts himself as a stakeholder trustee could have a duty to protect or advance the interests of all routinely affected groups as he had with protecting and advancing the interests of shareholders, without violating the rights of people who fall outside the stakeholder realm.

p.450

A management theory, whether a theory about managerial activity or about managerial fiduciary responsibility, has both immediate and long range consequences. However, theoretical issues may arise not only in the choice of a management theory but in how that theory may align with a theory of ethics more generally. The formation of a managerial judgment may require not only a choice among management theories but a choice of ethical theory as well. The implication of one management theory may prove incompatible with the conclusion of an ethical theory or vice versa. To illuminate this more fully, some of the major ethical theories are sketched in the next section.

The following major ethics theories have been utilized to explain dimensions of optimal ethical business management practice (Hosmer 2010; Bowie and Werhane 2004). Major ethics theories can be divided into consequentialist and non-consequentialist categories but each theory has strengths and limitations (Timmons 2012).

A consequentialist ethics theory holds that the moral status of an action is determined by the impartially reckoned overall goodness of its consequences (Darwall 2003). This means that when a business manager keeps his promise to employees to raise their annual wages by 2 percent, that act is made morally obligatory and commendable by its good consequences or by the hypothetical good consequences of people accepting a rule that requires it (such as a rule requiring promise keeping).

The varieties of consequentialist ethics theories include ethical egoism and act and rule utilitarianism. Ethical egoism is the personal consequentialist position that maintains that one ought to act out of informed prudent selfishness to satisfy one’s desires or to get what one wants (Machan 2003). Ethical egoist managers, however, who become exclusively driven by personal long-term career success may so neglect the interests of others that they provoke a backlash or harm others.

Utilitarianism maintains that managerial actions are good if they are expected to produce the greatest quantity and quality of well-being for the largest number of those affected by the actions (Mill 1861). There are different variations of utilitarianism. Act utilitarianism maintains that the values of the consequences of concrete specific actions determine the moral status of actions. An action is good if it brings about at least as much net well-being as any other action the agent could have performed. Rule utilitarianism maintains that an action is good if and only if it is allowed by a rule with as high a utility as any other alternative rule applying to the situation. A manager who is a rule utilitarian asks what set of rules or moral codes a society should accept so as to maximize human well-being in the long run. So, individual actions of breaking promises or unequally distributing benefits and burdens in society may, in the short run, maximize utility, but are morally objectionable from the rule utilitarian view but not necessarily from the act utilitarian view. Managerial proponents of the market system (as constituted by rules of various sorts), for instance, regard the free market as a powerful mechanism for maximizing economic utility since it provides goods and services at prices that allow individuals and societies to satisfy efficiently their desires, preferences and expectations.

p.451

A non-consequentialist ethics theory holds that the moral status of an action is not determined by the impartially reckoned overall goodness of its consequences but entails consideration of moral constraint, character, or context. There are different varieties of non-consequentialist ethics theories including: moral duty theories, contractarian moral theory, virtue ethics theory and contextual ethics theory.

There are two major moral duty theories: Kantian ethical theory (Kant 1785/1993) and Ross’s common sense moral theory (Ross 2003). Kantian ethics is preeminently an absolute deontological (duty-based) theory focused on right conduct. From Kant’s point of view, an action has moral worth (and thus a business management decision has moral worth) only if performed by an agent of “good will”—in other words, only if the motive for the decision and the action is moral obligation. The main moral obligation for Kant was to act in accord with the categorical imperative, an absolutely binding duty, variously formulated as a deep respect for universal moral law and persons. Kant argued that one’s duties could be ascertained by considering whether the maxim of one’s action could be willed to be universal moral law. Consistent with this notion is the idea that individuals (thus, managers) must not treat people exclusively as a means to their ends because every person has rational autonomy deserving of moral respect. In sum, Kant expected individuals to make the right decision for the right reasons.

Kantian ethical theory has been criticized for its overemphasis on duty since people can do the right thing for a variety of commendable prudential and sympathetic reasons. In addition, Kantian ethical theory has difficulty providing a correct decision procedure because, given the multiplicity of relevant maxims associated with any action, one can use Kant’s proposed maxims to derive inconsistent moral verdicts about the same action.

W.D. Ross’s common sense moral theory maintains that while there are no absolute moral duties there are common prima facie obligations that must be acted upon by managers unless they conflict on a particular occasion with an equal or stronger obligation (Ross 2003). These duties include beneficence, fidelity to one’s promises, gratitude, justice, non-maleficence, reparation, and self-improvement. On this view, every manager would have an unconditional contractual moral obligation and duty to prioritize these prima facie duties. When prima facie duties conflict, the preponderance of evidence and argumentation will determine the relative priority of each duty. Although Ross’s common sense theory has been praised for its intuitive appeal and ability to achieve the same ends as Kantian ethical theory without relying on the latter’s absolute inflexibility of moral standards, the theory seems to entail that in cases of multiple duty conflicts there may not be a single right action because there would be no way to determine a moral verdict between two or more actions of equal moral weight in the circumstances.

Contractarian moral theory maintains that morality is to be based upon a formal or informal agreement made between parties such that each party will agree to refrain from inflicting harm or damage to other parties provided that the other parties agree to do likewise and that they will keep whatever agreements they voluntarily make now and in the future (Gauthier 1986). Although the general theory is praised for its open-ended moral inclusiveness, since any party at any time can make a contractual agreement to improve a situation, it is difficult and risky to determine whether the party one is about to contract with will or will not prove to be a fellow cooperator. Moreover, in the case of a notable application to business ethics (Donaldson and Dunfee 1999), the contractarian element seems weakly justified and it is not clear how diverse individuals are to discern the overarching agreements (or “hypernorms”) enshrined in the particular application.

p.452

Virtue ethics theory maintains that regular cultivation of the acquired disposition to think, feel and act ethically determines the moral value of persons. For the virtue ethicist, building character—the sum of individual virtues and vices that indicate the degree of readiness to act ethically—the habitual development of virtues is what life and managing ethically is all about (Sison 2017). Virtue ethics theory is agent-centered, not act-centered or consequence-centered; it is concerned with being rather than doing and attempts to answer the question, “What sort of person should I be?” rather than “What should I do?”

Aristotle argued that cultivation of the classic cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, temperance and justice was essential to achieve happiness, which he regarded as the natural quality of a whole human life characterized by the degree to which the following goods were secured and maintained: health, wealth, knowledge, friendship, good luck and virtue (Aristotle 350bc/1985). He maintained that there was a difference between having a good time (maximizing pleasurable utility) and leading a good life (maximizing happiness) and that the latter outcome was to be morally preferred to the former (Sison 2016). To this list of virtues, contemporary feminist virtue theorists have added the virtue of care as exemplified in relationships that may be unchosen, intimate and among unequals (Gilligan 1982). There have been other categories of virtues, some of which have been applied to business managers including competence, toughness, resilience, and resourcefulness among others, but ultimately a business manager’s character is judged on overall trustworthiness (Solomon 1999). More recently, Deirdre McCloskey has offered a robust narrative of the ways in which the virtues render commercial life possible and ethically successful (McCloskey 2006). One example of a step toward developing managerial character, though hardly emblematic of the kind of ethical habituation embraced by Aristotle or other ethics theorists, is that taken by some business school faculty and graduate students who have expressed their strong moral expectations for future higher professional, social and environmental responsibility standards for business managers by publicly endorsing and signing an MBA oath (Anderson and Escher 2010).

Virtue ethics theory has been criticized for its indeterminacy since a virtuous agent possesses a range of virtues with no absolute rank ordering that determines what the virtuous agent should do. Moreover, some contend that what is recognized and commended as virtuous may be relative to a culture or epoch.

The choice of ethics theories may make a critical difference in moral performance. For example, a corporate manager who endorses ethical egoism may unilaterally shortchange the company pension plan in order to make the company appear to be more profitable than it is, thereby inflating the value of the company stock and his stock options. When at a later date the pension funding falls short and the workers get less than what they were due (or the taxpayers have to make up the part of the shortfall), the ethical egoist manager can move on to another company and still benefit at the expense of others. By contrast, another corporate manager in the same company who endorses contractarian moral theory would object to the deliberate shortchanging of the company pension plan and would fully fund it on the grounds of the importance of honoring contractual promises.

Selected theoretical issues in management ethics

In this section we take up two theoretical issues of management ethics. The first of these focuses on the conceptual relationship between management theories and ethics theories: Should a single moral theory be allied to a specific management theory? Or does moral and efficacious management require a pluralistic view of ethics and management? Moral monism suggests the former, pluralism the latter. A second theoretical concern probes a more fundamental question: To what extent can theory, whether managerial or normatively ethical, guide conduct? We shall sketch some of the positions one might adopt in relation to these questions.

p.453

Monism versus pluralism

One theoretical issue of management ethics is the difference between moral monism and limited moral pluralism. Moral monism maintains that moral conduct is and ought to be determined on the basis of a single management theory linked to a single ethics theory. For example, a manager who is a Kantian might rely on rational goal management theory on the assumption that the manager has a clear duty to lead the firm in the optimal way. Or a utilitarian might manage a corporation in accordance with human relations theory, perhaps on the assumption that the encouragement and maintenance of employee morale, as well as attention to external stakeholders, is the overall key to success. In these cases, one would need a theoretical justification not only for the normative theory but for the management theory as well. Then a third justification would be required to show that either the normative moral theory entailed the management theory or that the management theory was not inconsistent with the normative theory. This sort of perspective assumes that one theory of morals and one theory of management can be allied to provide clear guidance to a manager.

The thesis of limited moral pluralism is that the complexities of management require input from a plural (but limited) number of management and ethics theories. Simply enough, these theories combine the pluralistic perspectives of distinct management theories along with pluralistic perspectives of distinct moral theories. One form of limited moral pluralism is the combination of a competing values management framework (Quinn et al. 2015) with the integrity capacity moral framework (Petrick 2008; Petrick and Quinn 2001).

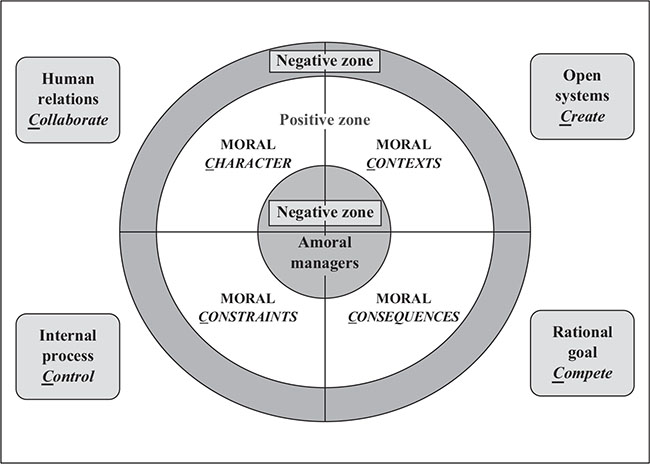

From the competing values framework, core managerial role performance is the outcome of efforts to compete (organizational effectiveness), control (operational efficiency), collaborate (stakeholder engagement), and create (continual innovation as well as adaptation to opportunity), all in a dynamic setting of supply and demand (Cameron et al. 2007). For heuristic purposes (Gigerenzer and Hertwig 2015), these are sometimes referred to as the four Cs (see Figure 26.1) of management competence: competing, controlling, collaborating, and creating.

This framework incorporates four major theories of management. The four management theories and their emphases (in italics) are designated outside the circle in their appropriate quadrants of emphasis: the rational goal theory emphasizes competing effectively in the external market, the internal process theory emphasizes controlling efficiently within the organization, the human relations theory emphasizes collaborating with employees and other stakeholders, and the open systems theory emphasizes creating new products or environments and accessing external resources.

Each management theory is typified as having an opposite: for example, the human relations theory stands opposed to the rational goal theory and the open systems theory runs counter to the internal process theory. Although an open systems manager is concerned with adapting to the continuous changes in the environment, the internal process manager is concerned with maintaining stability and continuity within the system. In addition, complementary parallels among the theories are important. The rational goal and internal process theories share an emphasis on control. The open systems and rational goal theories share an emphasis on external focus outside the firm. The internal process and human relations theories share an internal focus. And the human relations and open systems theories share an emphasis on flexibility. The overarching idea of this framework is that managerial excellence reflects a balance among these four competing and complementary theories.

p.454

Figure 26.1 Managerial competing values and integrity capacity framework.

Source: From: Encyclopedia of Business and Finance, 3rd edition © 2014 Gale, a part of Cengage, Inc., reproduced with permission: www.cengage.com/permissions.

The relationship of the four core major theories of management (Figure 26.1) is organized in terms of two axes, as long as economic exploitation is avoided and reliance on evidence-based decision-making is the norm. The vertical axis ranges from individual and collective flexibility at the top to control at the bottom. The horizontal axis ranges from an internal organizational focus at the left to an external focus at the right. Each major management theory fits into one of the four quadrants of emphases formed by the intersection of the two axes. Furthermore, the negative zones of managerial quadrant competence are indicated by the central bullseye circle that represents defective performance (amoral management) and the outer ring that represents excessive overemphasis.

From the ethics perspective, integrity capacity is regarded as the intangible strategic asset for which managers are held accountable and is composed of the aggregate individual and collective capability for repeated process alignment of moral awareness, deliberation, character and conduct that demonstrates sound balanced judgment, cultivates moral development and promotes supportive systems for ongoing moral decision making (Petrick and Quinn 2001). Judgment is one key dimension of integrity capacity that requires the balancing of moral consequences, moral constraints, moral character and moral contexts. Three normative ethics theories (Figure 26.1) are designated inside the positive zone of the circle in their appropriate quadrants of emphasis. These three theories are joined by a fourth theory that is less normative than contextual or organizational.

This fourth theory, contextual ethics, is invoked to point out how organizational and extra-organizational conditions and circumstances of decision-making and behavior may shape and influence the moral judgment and conduct of individuals. A supportive organizational and extra-organizational moral environment is more likely than a corrupt one to elicit managerial moral performance. For instance, managers can design and institutionalize the context of the organizational work culture to either support or inhibit moral judgment and conduct. Ethical managers design and institutionalize ethical work cultures that not only prevent criminal misconduct but also enable responsible conduct and collective commitment to moral behavior by organizational stakeholders (Collins 2012). Such an ethical work culture has been described as consisting of processes and norms that in the aggregate contextually promote the moral and effective functioning of the organization. The organizational features that might promote ethical conduct include, for example, codes of conduct, ethical audits (Petrick and Quinn 1997) and the promotion of ethical leadership (Laasch and Conaway 2014), among others. Well designed and robust ethical cultures help incentivize and reinforce morally commendable conduct prescribed by ethical theories and traditions.

p.455

On the pluralist view each ethical theory, along with the contextual considerations, is critical to the analysis and resolution of management ethics issues. Moreover, the way people in fact manage may suggest, implicitly or explicitly, their accustomed moral value priorities and emphases: for example, a rational goal “bottom line” manager may be inclined to emphasize consequential ethics.

From this limited moral pluralism perspective, improving ethical managerial performance requires that managers move out of their intuitive moral comfort zones and engage in structured dialogue and discourse to elicit and consider the most compelling evidence and soundest arguments (and structures) for a course of action. After critically evaluating these inputs from the core moral and contextual theories, the manager must make a decision on the basis of the preponderance of evidence (Petrick 2014). For example, a rational goal manager, reared and educated in secular and liberal institutions, may be predisposed not to hire an employee who is an evangelical or fundamentalist Christian. Yet, if he opens his mind to the inputs (evidence and arguments) of ethics theories, not to mention the obvious constraint of a federal government that guarantees a right to non-discriminatory treatment, then he may make a more balanced ethical decision that will be better in the long run for him and his business. Now it is true that some of these additional moral theory inputs may be accorded different weights, but the switch from the moral monism of a possible short term, perhaps utility-based, discrimination decision to a reflective, mindful non-discrimination moral decision is the foundation for ethical management performance from the limited moral pluralism perspective.

A choice between the monistic or pluralistic perspective requires an estimate of each moral theory and their contextual requirements, as well as a consideration as to whether a balancing of theories and contexts can be rendered clear. If there is some need for balancing then there must also be a justification for the inclusion of specific management theories, as well as specific ethical theories (and their contextual implications or requirements). It is true that the limited moral pluralism model allows broader, more adequate consideration of multiple voices in policy decisions, but it also leaves decision-makers without much of a standard. Indeed, the framework may be criticized because it offers a high level of complexity, demands intense moral discourse from and among managers, and the structural architecture may take on a life of its own that is less than relevant to practical moral decision making. The question of how a manager makes ethical decisions leads to a second kind of theoretical question.

Theory and practice

A second theoretical concern pivots on this point: to what extent should theory affect business practice, at least in the moral realm? One motivation for this concern rests in a fundamental question about the role of theory in guiding or directing conduct. One way to approach this question is to return to philosophical examinations of the place of theory in everyday conduct (Oakeshott 1991) or the role of business ethics and businesspersons (Crisp 2003).

p.456

A potential conflict between theory and practice is suggested by recent work in psychology. Consider that many might think that individuals can derive sound normative moral principles through the structured development of reason alone (Gewirth 1980; Singer 2003). An individual can overcome unconscious psycho-social moral biases, consciously reflect critically on moral reasons, distinguish ethically relevant facts, logically evaluate moral theories and their alternative resolutions, engage in rational moral dialogue, and finally make a rationally responsible moral decision (Gewirth 1980). This is an appealing picture of the power of autonomous reason.

However, in a recent study Jonathan Haidt casts doubt on the power of reason (and grand theories) to guide conduct (Haidt 2012). Against the perspective of moral rationality, Haidt posits a theory of moral foundations. Moral foundations theory emerges from evolutionary psychology and maintains that individuals are unconsciously psycho-socially biased in the extent and degree to which in making moral decisions they intuitively gravitate to six moral foundation polarities: care/harm, liberty/oppression, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. His work suggests that morality entails the sublimation of individual conscience into the broader collective emotions of a tribe or organization, all in order to feel the power of group righteousness.

According to Haidt, these six innate moral intuitions serve unconsciously to differentiate politically liberal managers from politically conservative managers. Unlike the conservative managers who address all six polarities, liberals tend to focus only on three moral polarities (care/harm, liberty/oppression, fairness/cheating). These differences in unconscious moral priorities affect directly managerial decision making and performance, and the reduced focus of liberal managers leave them at a career disadvantage, at least in institutional contexts that reward group cohesion and teamwork.

Such research findings help to explain the compliance engendered and expected by managers who seek to address all six polarities. The task of management ethics, however, is to be able to critically challenge personal moral biases and to enlarge the scope of factors considered in moral decision making and performance. Whether contemporary business managers will rise to the challenge to rationally resolve theoretical issues in management ethics or will simply conform to institutional expectations will determine the quality of future managerial moral performance.

Concluding remarks

The focus of this chapter has been on treating the state of the discipline regarding the critical importance of understanding the organized complexity of theoretical issues in management ethics. The spotlight has shown on three areas: 1) major management theories and their strengths and limitations; 2) major ethics theories and their strengths and limitations; and 3) two selected theoretical issues in management ethics. What makes an issue in management ethics theoretical has to do with how the conceptual relationship between management theories and ethics theories is interpreted to relate to managerial moral performance. Management and ethics theories matter to managerial moral performance. Increased awareness of the opportunities and challenges presented by theoretical issues in management ethics can contribute to improved managerial moral performance in the future.1

Essential readings

The essential works on theoretical issues in management ethics include LaRue Hosmer, The Ethics of Management (2010), Norman Bowie and Patricia Werhane Management Ethics (2004), and Joseph Petrick and John Quinn Management Ethics: Integrity at Work (1997). For a comprehensive and critically foundational perspective on managerial competence see Robert Quinn, David Bright, Sue Faerman, Michael Thompson, and Michael McGrath, Becoming a Master Manager: A Competing Values Approach (2015), for international expectations for management ethics performance, see Oliver Laasch and Roger Conaway (2014) Principles of Responsible Management: Global Sustainability, Responsibility, and Ethics, and for more on moral theory see Mark Timmons Moral Theory (2012).

p.457

For further reading in this volume on the practical questions of management ethics, see Chapter 27, The ethics of managers and employees. Since the very nature of a business is relevant to theoretical considerations of management, see Chapter 13, What is business? On theoretical issues in marketing ethics, see Chapter 30, Ethical issues in marketing, advertising, and sales. An enlarged discussion of theories of normative ethics may be found in Chapter 5, Consequentialism and non-consequentialism. On moral pluralism as relevant to the ethics of entrepreneurship, see Chapter 16, The ethics of entrepreneurship. On the issues of theory and practice in business ethics, see Chapter 3, Theory and method in business ethics.

Note

1 A few of the ideas expressed in this chapter, along with Figure 26.1, received a preliminary expression in Petrick (2017).

References

Alvesson, M., T. Bridgman and H. Wilmott (eds) (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Critical Management Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, M. and P. Escher (2010). The MBA Oath: Setting a Higher Standard for Business Leaders. New York: Penguin.

Aristotle (1985 [4th century BCE]). Nicomachean Ethics. T. Irwin (trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Bowie, N. and P. Werhane (2004). Management Ethics. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bowie, N. (1999). Business Ethics: A Kantian Perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Cameron, K., R. Quinn, J. DeGraff and A. Thakor (2007). Competing Values Leadership: Creating Value in Organizations. New York, NY: Edward Elgar.

Collins, D. (2012). Business Ethics: How to Design and Manage Ethical Organizations. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Crisp, R. (2003). “A Defence of Philosophical Business Ethics,” in William Shaw (ed.), Ethics at Work: Basic Readings in Business Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1–14.

Darwall, S. (ed.) (2003). Consequentialism. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Donaldson, T. and T. Dunfee (1999). Ties that Bind: A Social Contracts Approach to Business Ethics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Fayol, H. (1916). General and Industrial Management. London: Pittman.

Freeman, E., J. Harrison and A. Wicks (2007). Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation and Success. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” New York Times Magazine (September 13), 32–33 and 123–126.

Gauthier, D. (1986). Morals by Agreement. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gewirth, A. (1980). Reason and Morality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). “Bad Management Theories are Destroying Good Management Practices,” Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4:1, 75–91.

Gigerenzer, G. and R. Hertwig (2015). Heuristics: The Foundations of Adaptive Behavior. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind. New York, NY: Pantheon.

p.458

Hosmer, L. (2010). The Ethics of Management, 7th edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Kant, I. (1993 [1785]). Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, James W. Ellington (trans.), 3rd edition. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Laasch, O. and R. Conaway (2014). Principles of Responsible Management: Global Sustainability, Responsibility, and Ethics. Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.

Lawrence, A. and J. Weber (2017). Business and Society: Stakeholders, Ethics and Public Policy, 15th edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Lawrence, P. and P. Lorsch (1967). Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Machan, T. (2003). The Passion for Liberty. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Mayo, E. (1933). The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization. New York, NY: Macmillan.

McCloskey, D. (2006). The Bourgeois Virtues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mill, J.S. (1861). Utilitarianism. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Mitnick, B. (2008). “Theory of Agency,” in R. Kolb (ed.), Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society. 5 vols. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, vol. 1, 42–48.

Norman, W. (2013). “Stakeholder Theory,” in Hugh LaFollette (ed.),The International Encyclopedia of Ethics. Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons.

Oakeshott, M. (1991 [1948]). “The Tower of Babel,” in Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays, new and expanded edition. Indianapolis, IL: Liberty Fund, 465–487.

Petrick, J. (2008). “Using the Business Integrity Capacity Model to Advance Business Ethics Education,” in D. Swanson and D. Fisher (eds), Advancing Business Ethics Education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 103–124.

Petrick, J. (2014). “Strengthening Moral Competencies at Work through Integrity Capacity Cultivation,” in L. Sekerka (ed.), Ethics Training in Action. Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 207–228.

Petrick, J. (2017). “Theoretical Issues in Management Ethics and Moral Performance,” Journal of International Management Studies 12:1, 47–54.

Petrick, J. and J. Quinn (1997). Management Ethics: Integrity at Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Petrick, J. and J. Quinn (2001). “The Challenge of Leadership Accountability for Integrity Capacity as a Strategic Asset,” Journal of Business Ethics 34:331–343.

Quinn, R., D. Bright, S. Faerman, M. Thompson and M. McGrath (2015). Becoming a Master Manager: A Competing Values Approach, 6th edition. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Ross, W.D. (2003). The Right and the Good. London: Clarendon Press.

Rousseau, D. (ed.) (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scarre, G. (1996). Utilitarianism. London: Routledge.

Singer, M. (2003). The Ideal of a Rational Morality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sison, A. (2016). Happiness and Virtue Ethics in Business. London: Cambridge University Press.

Sison, A. (ed.) (2017). Handbook on Virtue Ethics in Business and Management. London: Springer.

Solomon, R. (1999). A Better Way to Think About Business: How Values Become Virtues. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, F. (1911). The Principles of Scientific Management. New York, NY: Harper.

Timmons, M. (2012). Moral Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.