p.184

Kenneth E. Goodpaster

In this chapter I examine a broad set of approaches to organizational decision making that I will refer to as “stakeholder thinking.” Stakeholder thinking is a normative ethical approach to decision making that emphasizes corporate responsibilities to individuals, groups, and institutions including, when applicable, fiduciary obligations owed to investors and shareholders. I favor the phrase “stakeholder thinking” over “stakeholder theory” because it is more generic.1 Understood in this way, stakeholder thinking is frequently offered as a proxy for what some would call the “conscience” of the corporation.2

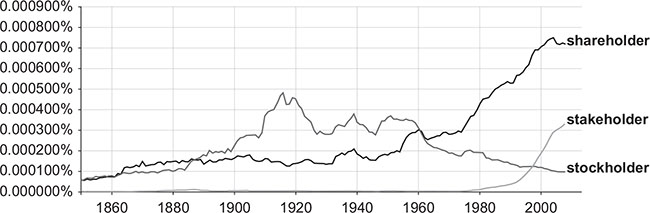

One way to get an historical perspective on stakeholder thinking is to view a Google NGRAM of the frequency of the use of the word “stakeholder” in relation to “stockholder” and “shareholder” since 1850. It seems clear from Figure 11.1 below, that the 1970s saw the genesis of the language of stakeholder thinking and it has grown dramatically since then. In the post-WWII period, the language of “shareholders” has gradually displaced the language of “stockholders.” Stakeholder thinking emerged during this period by contrasting itself with fiduciary shareholder thinking as a view about corporate governance. Eventually, however, it emerged as a view about how managers should make decisions.

Figure 11.1 Google NGRAM of “stakeholder” in relation to “stockholder” and “shareholder.”

p.185

Throughout this chapter I will affirm the distinctiveness of fiduciary obligations, while suggesting that the nature of business obligations that go “beyond” them need not and should not be expressed as impartial fiduciary duties to stakeholder groups. Furthermore, I will argue that stakeholder thinking, often celebrated as a successor to the shareholder paradigm, is itself in need of a successor along with the shareholder paradigm. This successor—which is, in fact, the very framework that underlies these paradigms—I will call comprehensive moral thinking. A recent illustration of this mindset can be found in the reflective practice of John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods (Mackey and Sisodia 2013).

The first section of the chapter sets the stage historically and conceptually regarding stakeholder thinking. In the next section I clarify the idea of conscience, suggesting that its essence lies in what Josiah Royce, at the end of the nineteenth century, called “the moral insight.” We are then in a position to offer a concise account of corporate conscience. In the third section I point out how stakeholder thinking is more of an obstacle to corporate conscience than a proxy for it. This discussion also reveals several criteria that an adequate account of corporate conscience must satisfy: a) moral substance/depth; b) specification of both the domain and the range (agents and recipients) of non-fiduciary duties, and c) a more robust and practical view (than markets and laws afford) of the “goods and services” for which a business economy exists. In the fourth section I offer suggestions about a comprehensive approach to corporate conscience based on two principles, human dignity and the common good. In the last section I draw out some implications for business education.

Twenty years ago, [I held] that corporate powers were powers in trust for shareholders while Professor Dodd argued that these powers were held in trust for the entire community. The argument has been settled (at least for the time being) squarely in favor of Professor Dodd’s contention.

(Adolf Berle 1954: 169)

The quotation above from Adolf Berle indicates that the debate between Berle (at Columbia) and E. Merrick Dodd (at Harvard Law School)—a foreshadowing of what today is called the shareholder–stakeholder debate—dates back at least to the 1930s.3

The term “stakeholder” seems to have originated in a 1963 internal memorandum at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). It defined stakeholders as “those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist” (Freeman and Reed 1983: 89). Professor R. Edward Freeman, in his book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, expanding on the SRI characterization, defined the term this way: “A stakeholder in an organization is (by definition) any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” (Freeman 1984: 46). Examples of stakeholder groups (beyond stockholders) are employees, suppliers, customers, creditors, competitors, governments, and communities. It is useful to note that these two definitions of “stakeholder” are not the same, and that one of the characteristics of “stakeholder thinking” from its inception has been disagreement over the breadth of its primary idea. Indeed some have argued that the stakeholder concept can easily extend to “the whole of the human race” (Langtry 1994: 432). Such a broad view would provide a recipe for decisional paralysis. On the other hand, a narrower interpretation can reduce ethics to clashes of competing interest groups (Heath 2006).

In addition to the unresolved questions of narrowness or breadth in defining “stakeholder,” there are questions about applying stakeholder thinking to corporate governance in contrast to applying it to corporate management. This distinction is clarified by John Boatright this way:

p.186

Stakeholder management goes wrong by (1) failing to appreciate the extent to which the prevailing system of corporate governance, marked by shareholder primacy, serves the interests of all stakeholders, and (2) assuming that all stakeholder interests are best served by making this the task of management rather than using other means.

(Boatright 2006: 107)

The suggestion here is that the economic and legal structure of the modern corporation, its governance structure, is and should be distinct from the principles by which the management of the corporation operates, its decision-making norms (Stone 1991).

Despite these tensions about meaning, many would argue that the most significant normative generalization in post-WWII business ethics is represented by the phonemic shift from stockholder to stakeholder. Corporate responsibility was often defined by business practitioners as primarily the fiduciary responsibility of managers to stockholders. Stakeholder thinking seems to insist that decision makers widen their perspectives to include other affected parties. Indeed, today, it is common to claim that the essence of business ethics lies in extending stockholder concern to stakeholders generally. With this extension in mind, there exists a wide literature on the meaning and implications of the shift from stockholder to stakeholder thinking. The literature addresses questions such as the following:

Is stakeholder thinking a descriptive/empirical perspective on decision making? Or is it normative?

(Donaldson and Preston 1995)

And if normative, is it moral or non-moral?

(Donaldson and Preston 1995)

Is any theory of stakeholding truly a theory in any meaningful sense of that term?

(Norman 2013)

How should we identify (and perhaps even rank order) the principal stakeholders in a business context?

(Freeman 1984, 2014; Langtry 1994)

How should we weigh potentially conflicting stakeholder interests?

(Heath 2006; Freeman et al. 2007)

Does stakeholder thinking generalize beyond business corporations to other organizational forms (unions, government or public sector entities, NGOs)?

(Hasnas 2013)

What does stakeholder thinking imply (if anything) for corporate governance, e.g., for representation on corporate boards?

(Stone 1991; Boatright 2006; Agle et al. 2008)

What are the implications of stakeholder thinking for the traditional fiduciary obligations of management and the board?

(Goodpaster 1991, 2007a, 2010; Marcoux 2003; Paine 2003)

Should stakeholder thinking influence the business school curriculum?

(Smith and Rönnegard 2014)

These and other questions indicate the conceptual variety and range of the stakeholder literature (Hasnas 2013).

p.187

Conscience: personal and institutional

In the society of organizations, each of the new institutions is concerned only with its own purpose and mission. It does not claim power over anything else. But it also does not assume responsibility for anything else. Who, then, is concerned with the common good?

(Peter Drucker “The Age of Social Transformation,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1994: 7)

Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary defines “conscience” as “the inner sense of what is right or wrong in one’s conduct or motives, impelling one toward right action: to follow the dictates of conscience.”

I believe that at the core of conscience lies a pair of complementary tensions that needs to be managed—a tension on the personal level between self-love and love of others and on the public corporation level between shareholders and non-shareholding stakeholders (see Goodpaster 2007a: Chaps 3, 4; Goodpaster 2007b). At the personal level, “self-love” should not be confused with mere self-interest or selfish desires, just as “love of others” should not be confused with merely satisfying the desires of others. Love is about looking after the good, not simply the desires, of the loved one. In this respect, both self-love and love of others are normative concepts. This clarification should help us at the institutional level when we contrast fiduciary obligations to stockholders with obligations to stakeholders. The contrast is not between corporate selfishness and corporate altruism. Instead, it is a moral distinction between an institution’s fiduciary duties to its providers of capital and its duties to other stakeholder groups that are morally grounded in different ways.

Nineteenth-century Harvard philosopher Josiah Royce believed that all of ethics was grounded in what he called the moral insight (a precursor to what philosophers in the twentieth century called the “moral point of view”). Royce described the moral insight this way:

The moral insight is the realization of one’s neighbor, in the full sense of the word realization; the resolution to treat him unselfishly. But this resolution expresses and belongs to the moment of insight. Passion may cloud the insight after no very long time. It is as impossible for us to avoid the illusion of selfishness in our daily lives, as to escape seeing through the illusion at the moment of insight. We see the reality of our neighbor, that is, we determine to treat him as we do ourselves. But then we go back to daily action, and we feel the heat of hereditary passions, and we straightway forget what we have seen. Our neighbor becomes obscured. He is once more a foreign power. He is unreal. We are again deluded and selfish. This conflict goes on and will go on as long as we live after the manner of men. Moments of insight, with their accompanying resolutions; long stretches of delusion and selfishness: That is our life.

(Royce 1865: 155–6, emphasis added)

Royce’s idea of the moral insight lies at the foundation of the “Golden Rule,” the oldest and most widely shared ethical precept known to us. His language in the above passage is significant, and it will be relevant in the remaining parts of this chapter and as we consider, in the next section, some shortcomings of stakeholder thinking.

Over the past two centuries Western society has become what Peter Drucker referred to as a “society of organizations” (1978: 12). Personal or individual actors on the public stage have been joined (if not replaced) by institutional or organizational actors. If we join the idea of a “society of organizations” with the fact that, by 1868, corporations were firmly established under American law as “legal persons,” it is not surprising to find that corporations are today expected to behave with consciences analogous to individual persons (Goodpaster and Matthews 1982).

p.188

The “legal personhood” of the corporation is not the same as moral personhood. Moral personhood requires that the corporation have a degree of discretion or freedom under the law and in practice, so that the ideas of responsibility and conscience can make sense. Without such discretion, corporate leaders might be constrained to make decisions solely on the basis of non-moral economic considerations. Only an organization that is relatively free can be asked to be responsible; an organization that is merely an arm of the state can only be compliant. As corporate law scholar Lyman Johnson has pointed out:

It is . . . the very discretion afforded by law that makes discussions of corporate responsibility possible and meaningful. Without such discretion—as, for example, if managers really were legally required to maximize profits—advocacy of socially responsible behavior would truly be academic because managers would be prohibited from engaging in such conduct.

(Johnson 2011: 17–18)

Organizations are in some ways macro-versions (projections) of ourselves as individuals—human beings writ large. We can sometimes see more clearly in organizations certain features that we want to understand better in ourselves, but often the reverse is true. Managers and leaders can often benefit from what we understand about ourselves as individuals. I have referred to this analogical approach in the past as the “moral projection” principle. Formally, it can be stated as follows:

Moral Projection Principle. It is appropriate not only to describe organizations and their characteristics by analogy with individuals, it is also appropriate normatively to look for and to foster moral attributes in organizations by analogy with those we look for and foster in individuals.

(Goodpaster 2005: 363–364)

Corporate responsibility is the projection of moral responsibility in its ordinary (individual) sense onto a corporate agent. Corporate conscience can evolve from purely self-referential status (e.g., public relations) through the status of an environmental constraint (e.g., legal or regulatory requirements) to being an authentic, independent management concern. Such an evolution represents a maturation process analogous to the development of conscience in individuals (Piaget 1932). Sociologist Philip Selznick articulated this idea six decades ago (1957) when he wrote about “character formation” as an important area of exploration for those who would understand the decision making of organizations. Leadership, according to Selznick, was about institutionalizing values. We are now in a position to look more critically at the suggestion that stakeholder thinking should be adopted as a proxy for managerial decision making and corporate conscience.

Is stakeholder thinking more an obstacle to than a proxy for corporate conscience ?

So we must think through what management should be accountable for; and how and through whom its accountability can be discharged. The stockholders’ interest, both short- and long-term, is one of the areas, to be sure. But it is only one.

(Peter Drucker, Harvard Business Review, September 1988: 73)

p.189

Given the context of stakeholder thinking and the idea of corporate conscience limned above, one might think that the former is a solid candidate for operationalizing the latter. But all is not sweetness and light when it comes to overlaying stakeholder thinking onto corporate conscience. Indeed, some have argued that the two are not only incongruent, but that stakeholder thinking is actually an obstacle to responsible (conscientious) corporate decision making. And there are a number of other concerns about the adequacy of stakeholder thinking in its conventional formulations that may give us pause.

A fiduciary argument against stakeholder thinking

There is a paradox in stakeholder theory:

It seems essential, yet in some ways illegitimate, to orient corporate decisions by ethical values that go beyond fiduciary shareholder obligations to a concern for stakeholders generally.

(Goodpaster 1991: 63)

The paradox arises because there is an ethical problem whichever way management chooses to go. The mindset behind the paradox is conflicted by a concern that the “impartiality” of stakeholder thinking simply cuts management loose from certain well-defined bonds of “partial” (fiduciary) shareholder accountability (Goodpaster 2007a: Chap. 4). My suggested way out of the paradox was to distinguish between two different kinds of ethical obligations—fiduciary and non-fiduciary—and to argue that management’s fiduciary obligations to shareholders were different in kind from management’s obligations to non-shareholding stakeholders (Goodpaster 1991: 67).

This line of argument stands out as a significant challenge to a commonly held version of stakeholder thinking, namely, the view that the fiduciary relationship between management and shareholders is not distinctive, and that the conscience of the corporation should instead be guided by a “multi-fiduciary” view. A multi-fiduciary view (for example, Evan and Freeman 1988: 103–4) holds that management has fiduciary duties to investors, yes, but also to other stakeholders like employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, and perhaps even the natural environment. Alexei Marcoux (2003), among others (Hasnas 1998; Heath 2006), has argued that such a view of stakeholder thinking is either incoherent or morally inadequate.

Marcoux’s critique of the multi-fiduciary stakeholder view is based on his analysis of the nature of fiduciary duties. He argues that the attribution of fiduciary duties to physicians, lawyers, and others (including managers and boards of directors) calls for partiality toward their beneficiaries—and that this is incompatible with concurrent fiduciary duties to multiple third parties (impartiality) (Marcoux 2003: 19). Marcoux points out that “[t]o act as a fiduciary means to place the interests of the beneficiary ahead of one’s own interests and, obviously, those of third parties, with respect to the administration of some asset(s) or project(s),” adding that:

The multi-fiduciary stakeholder theory, rather than extending the fiduciary duties of managers to non-shareholding stakeholders (because it is conceptually and practically impossible), eliminates fiduciary duty altogether in favor of a consequentialist-like weighing and balancing of admittedly competing stakeholder interests.

(Marcoux 2003: 3; 5, original emphasis)

Marcoux’s argument does more than shed light on the special character of the fiduciary relationship. In the course of marshaling his argument against multi-fiduciary stakeholder theory, he makes a number of observations that relate to Royce’s moral insight—the working of conscience, both personal and institutional. Three of these observations deserve special emphasis:

p.190

Vulnerability, moral substance and depth;

Contractual incompleteness; and

Non-fiduciary obligations.

Throughout his discussion of the moral warrant for fiduciary duties, Marcoux emphasizes the vulnerability of the beneficiaries of those duties: “Vulnerability consists . . . in deficits of control and information that arise from the relationship, even in the absence of physical, mental, or financial weakness” (Marcoux 2003: 10). Taking advantage of a patient, a client or an investor by subordinating their interests either to the interests of the fiduciary (self-dealing) or to a quasi-utilitarian impartial calculation is emphatically morally wrong (Marcoux 2003: 11). One interpretation of this wrongness is that denying protection to the vulnerable does not respect their reality. Perhaps another way to make this point would be to say that fiduciary duties relate to beneficiaries directly, not indirectly through an impersonal calculus.

This is reminiscent of Royce’s account of the moral insight. My beneficiaries are not illusory or “unreal” as would be the case if I responded to their vulnerability using impersonal public policy reasoning. Marcoux insists that fiduciary duties are morally substantial (and elsewhere, morally deep) because they apply quite independently of “what benefits society in general” (Marcoux 2003: 12, 19). Royce tells us that we “see the reality of our neighbor . . . we determine to treat him as we do ourselves.” But often “we straightway forget what we have seen. Our neighbor becomes obscured” (Royce 1865: 155–6). For Royce, as for Marcoux, the substance or depth of our moral perception is direct, unmediated, and action-guiding.

In a similar spirit, Marcoux argues that “shareholders are the object of the fiduciary duties of managers because their contracts with the firm are fundamentally incomplete,” meaning that foreseeing and enumerating the ways in which the shareholders can be taken advantage of is virtually impossible (by comparison with other stakeholder groups such as suppliers, employees, and customers) (Marcoux 2003: 13, 18). The fiduciary duties of doctors to patients, lawyers to clients, and managers to shareholders cannot be reduced to contractual obligations—the vulnerabilities of the beneficiaries are more indefinable. This seems to be why we refer to fiduciary relationships as the basis for fiduciary duties—and why Marcoux describes them as morally substantial and morally deep.

Finally, Marcoux acknowledges that managers may have extensive non-fiduciary obligations to stakeholders, but he insists that “the relationship of non-shareholding stakeholders to the firm is of a morally different kind” (Marcoux 2003: 16, emphasis added). The nature of non-fiduciary obligations to non-shareholding stakeholders may well be extensive—and the relative “weights” of those obligations are not easily determined without significant contextual information. Indeed, such obligations might be as morally substantial (or morally deep) as fiduciary obligations, even if they are different in kind. As we shall see, this last point helps us to articulate “comprehensive moral thinking” adumbrated in the next section.

In summary, Marcoux’s fiduciary argument against conventional stakeholder thinking appears to be rooted in a fundamental respect for those who are vulnerable, such as patients in relation to doctors, clients in relation to lawyers, and investors in relation to managers. The “partiality” of the fiduciary relationship is not, of course, unconditional. This is what allows us to explore non-fiduciary relationships “of a morally different kind.” It remains to be seen a) whether these relationships with other stakeholders are “impartial” or simply “different,” and b) how best to “weigh” fiduciary duties in relation to non-fiduciary duties.

p.191

Let us now turn to a second cautionary critique of stakeholder thinking as a proxy for corporate conscience, its under-specification regarding both the parties responsible and the parties to whom the responsibility is owed.

The domain and the range of moral transactions

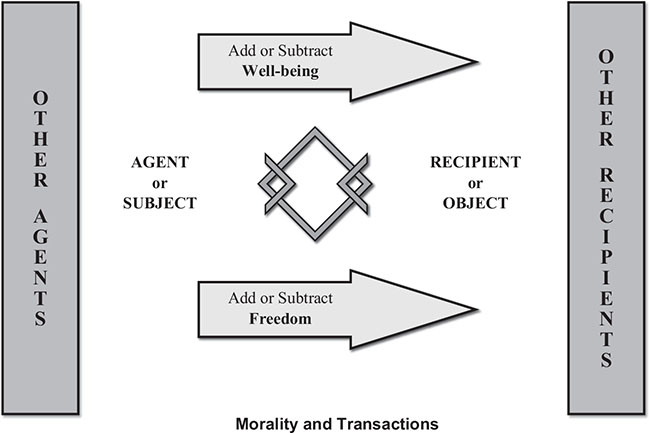

More than thirty-five years ago, University of Chicago philosopher Alan Gewirth insightfully conceptualized the field of ethics as having to do with transactions between agents and recipients: “where what is affected is the recipient’s freedom and well-being, and hence his capacity for action” (Gewirth 1978: 129). Applying Gewirth’s perspective to a discussion of corporate conscience, as in Figure 11.2 below, means that we need to attend to both agents (e.g., corporations and business leaders) and recipients (e.g., customers, employees, suppliers, etc.) as we scrutinize stakeholder thinking. An adequate stakeholder view needs to identify both those whose responsibility is to do stakeholder thinking (moral agents or actors)—and the relevant stakeholder groupings themselves (moral recipients).

Occasionally stakeholder thinkers will insist that business organizations cannot (and so should not) see themselves as responsible for achieving objectives that are beyond their spans of control (Nagel 1986; Goodpaster 2010). A long-defended maxim in moral philosophy is that “ought” implies “can.”

Environmental protection, public health, minimization of poverty, a culture of respect for life and liberty—these are aspirations for which no institution in any single sector (economic, political, civic) can be asked to take full responsibility. Realizing these aspirations would require the collaboration of institutions across sectors—which means that individual institutions have partial but not complete responsibility for the result. Business is responsible to the common good but not completely for it (for a similar distinction, see Donaldson and Walsh 2015: 198).

Stakeholder thinking can overlook business responsibilities for collaborative action—largely because it is framed in terms of what a corporation should do in relation to its own stakeholders. This is not simply a matter of how broadly or tightly the corporation understands its own stakeholders. Indeed, the notion of the community as a stakeholder of any corporation would seem to open the gates to a very broad interpretation of “affected parties.” The point in this context is not about the breadth of a given business’s set of stakeholders, but about a given business’s co-responsibility with other institutions for freedom and wellbeing in the human community (Goodpaster 2010, 2016). Businesses must do their part in support of the human community, even if that “part” takes them beyond their responsibilities to their typical stakeholding groups. If the problems facing humankind are problems that call for multi-sector cooperation, then responsible institutions need to develop new collaborative skills. They must develop a kind of “peripheral moral vision” and a willingness to work with other institutions to achieve what can only be accomplished together.

p.192

In summary, the grammar of stakeholders can be liberating, but it can also blind companies by shaping their ethical awareness in advance and thereby inhibiting moral imagination—an imagination that can see more deeply the relationships among social sectors (agency) and between companies and their stakeholders (fiduciary obligations and non-fiduciary obligations). Stakeholder thinking tends to “standardize” the relationships between businesses and their stakeholders using a consequentialist formula (“affect or affected by”) to identify moral relevance. But moral relevance may well take other, more qualitative, forms, e.g., attention to the vulnerable, keeping a promise, commitment to human dignity and the common good (Goodpaster 2010, 2016).

On the recipient side of moral transactions, the usual stakeholders whose freedom or well-being are under scrutiny include individuals, organized groups (e.g., labor unions) and, occasionally, whole societies (e.g., the water supply of a nation or the global climate). Recipients are those whose freedom or well-being deserve consideration. Two principal contexts in which stakeholder thinking often reveals a too-narrow ethical awareness of recipients are: consideration for non-human beings, and consideration for institutions or corporations themselves (Goodpaster 2007a: Chap. 1).

I use the phrase “moral consideration” (or the phrase “moral considerability”) deliberately to signal a level of moral awareness and concern that may or may not rise to the level of attributing moral rights to the recipient in question (Goodpaster 1978). Debates about animal rights, for example, can be spirited, but we need not take a position in those debates in order to accord to non-human living creatures some level of moral consideration. It seems clear to most of us on reflection that animals are part of the ecosystem that we inhabit and that we have certain stewardship responsibilities toward them. Stakeholder thinking as it is conventionally deployed, especially in business ethics, often excludes animals as a category deserving consideration alongside employees, consumers, suppliers, and shareholders. Also, while it is frequently true that considerations about ecological awareness can enter into stakeholder thinking as concern for future generations, it does not go without saying or argument that all of our stewardship responsibilities can be translated in this way.

Another context in which moral considerability can be overlooked by stakeholder thinking relates to our conduct toward corporations themselves. Much of business ethics, appropriately, attends to the responsibilities of corporations toward those parties affected by corporate decision making. But corporations themselves are often affected parties (stakeholders, moral recipients), for example in legal and judicial contexts as well as contexts like boycotts or labor strikes involving public displays of disapproval. Indeed, corporate competitors can come under moral scrutiny both as agents and recipients in the marketplace—even when the value of their competitiveness itself is affirmed.

The point to be made here in connection with moral recipients is not that corporations are identical in all respects with human beings as bearers of rights. There is much room for debate over the moral “personhood” of organizations. What is plausible, however, is that stakeholder thinking needs to accord moral consideration to organizations, just as it needs to accord moral consideration to non-human living creatures.

p.193

As we saw above, Royce’s moral insight (the “realization of one’s neighbor”) implies that conscience does not discriminate in its answer to the question “Who is my neighbor?” It is inclusive rather than marginalizing. Let us now turn to a third cautionary critique of stakeholder thinking: its lack of a normative account of value.

Stakeholder interests and the open question argument

The significance for stakeholder thinking of an underlying view of goodness (benefits and costs) often goes unnoticed, or at least unspoken. Views about goodness may be sidestepped in favor of a morally neutral appeal to something like “stakeholder choices, wants, desires, preferences, or satisfactions.” Perhaps such appeals escape notice because in an economic context, market reasoning and legality tend to dominate, and market reasoning and legality are quite at home with neutrality about what is good. Something has market value, it is often said, “if people are willing to exchange money for it.” Something is legal if the laws, as interpreted by the courts, say it is legal. To illustrate, let us take three principal stakeholder categories: customers, employees, and shareholders.

If “market value and legality” prevail in the provision of “goods and services” for customers or consumers then the quality of those goods and services in relation to fulfilled human lives is set aside or replaced by the current desires of customers.4 It is clear that markets and the law can and have underwritten the “goods” of pornography and cocaine, and the “services” of prostitution and drug-dealing. But these do not serve human freedom or well-being. An alternative? Companies seek to provide goods that are truly good and services that truly serve (Goodpaster 2011). But this calls for normative stakeholder thinking to develop an account of true goodness and true service.

If “market value and legality” prevail in the provision and design of employment, then the quality of that employment in relation to fulfilled human lives may be set aside or replaced by labor market imperatives driven more by efficiency than by humanity. An alternative? Companies appreciate the dignity of work and principles like subsidiarity (Pontifical Council 2012, §80 and Naughton et al. 2015). But this calls for normative stakeholder thinking about the freedom and well-being of employees’ lives that is deeper and more substantial than market value and legality.

If “market value and legality” prevail as metrics of fiduciary obligations to shareholders, then enhancing stock price and avoiding derivative lawsuits (legal actions brought by shareholders on behalf of a corporation against some or all of the officers of the corporation typically for offenses such as fraud or some form of fiduciary failure) become tests of corporate responsibility. Executive stock options may benefit from this pursuit, but it is not clear whether the vulnerability of shareholders is being exploited. The alternative? Providing care and loyalty to shareholders, bearing in mind both their responsibilities and their rights and—if I am a financial advisor—not assuming that wealth maximization alone serves the true interests of my beneficiaries. But again, this calls for normative stakeholder thinking about fiduciary and non-fiduciary obligations to investors.

Normativity about goods and services

Business decision makers need to understand that their normative views about goods, services, the dignity of work, and environmental responsibility are essential, and, whether they realize it or not, executives make assumptions constantly about what counts as “the good” for human beings (and how human goods are to be prioritized). Stakeholder thinking, as a systematic norm for business ethics, needs to offer a thoughtful account of the moral ground of business—what “good” business is supposed to do for people—be they customers, employees, or shareholders. It does not go without saying that simply satisfying stakeholder preferences is morally acceptable (Goodpaster 2010). In his encyclical, addressed to “all persons of good will,” Pope John Paul II put the matter this way: “Of itself, an economic system does not possess criteria for correctly distinguishing new and higher forms of satisfying human needs from artificial new needs which hinder the formation of a mature personality” (Centesimus Annus 1991, §36).

p.194

Stakeholder thinking as a proxy for corporate conscience cannot give carte blanche to serving the desires and demands of customers, employees, investors, or other stakeholder groups (even if the desires and demands of these groups were homogeneous, which they seldom are). It is clear that some “goods and services”—however much there might be a market for them—do not add value to the lives of such stakeholders, and stakeholder thinking that ignores the value-added issue is problematic. To be sure, there is room in this context for divergent views about “true goods and services.” The point is not to defend a dogmatic paternalism about human goods but to emphasize the importance of what Marcoux calls moral depth or substance in the stakeholder as much as in the shareholder realm.

Philosophically, this critique of stakeholder thinking is reminiscent of the “Open Question Argument” used over a century ago by G.E. Moore in his classic treatise Principia Ethica (1903). Moore could say regarding “goods” and “services” today: “Yes, these products and services or these corporate policies are supported by the market, but are they good?” Or “Yes, this corporate behavior is permitted by the law, but is it right?”

The third critique of stakeholder thinking as a proxy for corporate conscience, therefore, is that it must, but frequently does not, help decision makers to discern “true goods” for customers, dignified work for employees, and reasonable returns for shareholders.5 To do this, it seems clear, the advocate of stakeholder thinking in business must offer a normative account of human persons and their well-being.

Returning again to Royce’s moral insight (the “realization of one’s neighbor”), we can see that corporate conscience—by not fleeing from normativity—maintains or renews its awareness and avoids forgetting or obscuring the human (and non-human) reality of agents and recipients in the business system.

From stakeholder to comprehensive moral thinking

The development of peoples depends, above all, on a recognition that the human race is a single family working together in true communion, not simply a group of subjects who happen to live side by side.

(Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate, §53)

We have seen how stakeholder thinking might limit ethical awareness and inhibit moral imagination; we have also noted a tendency in stakeholder thinking to avoid normativity in relation to the content of stakeholder “interests, wants, and desires.” These criticisms are not trivial. But a more positive view of stakeholder thinking is that it provides us with a platform for a “transition” to a larger vision.

In 2008 Thomas Donaldson wrote of a “Normative Revolution” in our understanding of the business economy:

p.195

[M]anagers must ascribe some intrinsic worth to stakeholders. That is to say, a stakeholder, such as an employee, must be granted intrinsic worth that is not derivative from the worth they create for others. Human beings have value in themselves. Their rights stand on their own. These rights themselves are morally and logically prior to the way in which respecting their rights may generate more productivity for others or the corporation.

(Donaldson 2008: 175–76, original emphasis)

In some ways, with his use of the phrase “intrinsic worth,” Donaldson is extending Marcoux’s observation about the moral depth of the fiduciary relationship to shareholders, by applying it to stakeholders whose relationship to the corporation is non-fiduciary. This is a non-fiduciary version of Royce’s “realization of one’s neighbor.” Now we can clarify how “comprehensive moral thinking” extends management’s perspective, this time with special attention to the relationships among stakeholders in a wider human community.

Stakeholder thinking, without negating fiduciary thinking, expands the horizons of corporate responsibility: goods and harms for multiple parties. It emphasizes that many have “stakes” in corporate decision making, both fiduciary (in the case of shareholders) and non-fiduciary (in the case of employees, customers, suppliers, etc.). This is perhaps the most salutary contribution of stakeholder thinking to business and organizational ethics (Hasnas 2013).

Because of this expanded decision-making horizon, stakeholder thinking prepares us for a more holistic approach to corporate conscience, offering a stepping stone to enrichment on both the agent side of Gewirth’s moral transactions and on the recipient side. This more holistic approach is what I will call comprehensive moral thinking.

Hugh Heclo (2008) offers an interpretation of institutions and institutional thinking that helps to clarify comprehensive moral thinking. Heclo points out that institutions by their nature have a normative dimension:

by virtue of participating in an institutional form of life, there are more and less appropriate ways of doing things. These obligations are a kind of internal morality that flows from the purposive point of the institution itself.

(Heclo 2008: 85, emphasis added)

The “internal morality” of institutions is best understood using what W.D. Ross called prima facie obligations in relation to our participation in other institutions, e.g., the norms of family, work, and community (Ross 1988 [1930]). Also, in addition to the requirements of the “internal morality” of institutions in relation to one another, there is a deeper morality to which all institutions must be subject. To quote Heclo again:

Since institutions exist for people, they are to be judged along a moral continuum of good and bad according to what is needed for human beings to flourish as human beings. In order to deserve the designation of good, institutions ought to be doing what is good for us as human beings.

(Heclo 2008: 153)

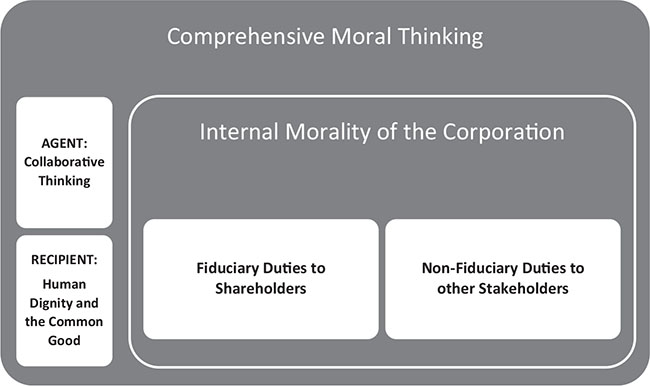

Figure 11.3, on the following page, depicts stakeholder and shareholder thinking as part of the internal morality of the corporation—and comprehensive moral thinking as an external check on “what is needed for human beings to flourish as human beings.”

p.196

Figure 11.3 A depiction of stakeholder thinking along with shareholder thinking as part of the internal morality of the corporation.

If we were to diagram the proposition, “Corporations are responsible to their stakeholders,” then comprehensive moral thinking would be depicted as shifting both the subject and the object of corporate responsibility. The shifting of the subject calls for attempts at collaboration with other responsible institutions. This often means sharing responsibility between private and public sectors. It can also mean engaging moral-cultural institutions (family, school, media, church), since usually no one of these sectors or institutions can achieve the common good alone. Comprehensive moral thinking means looking at society and its problems through a first-person-plural lens: “We need to address this issue.” Instead of thinking solely from within their institutional boundaries (according to their internal morality), corporate leaders (and, mutatis mutandis, political leaders and NGO leaders) who think collaboratively must migrate toward a more embracing perspective. To be persuasive, of course, this idea must be thoroughly vetted to avoid abuses of collaboration. The anti-trust regulatory framework in the US exists to preserve competition and to prevent collaboration against the common good.

The shifting of the object of corporate responsibility calls for more than the satisfaction of multiple stakeholders.6 It calls for seeing shareholders and other stakeholders as parts of a global community of interdependent participants each of whom deserves to be treated with dignity—the principal implication of Royce’s moral insight, “realizing one’s neighbor.”

The essence of the common good lies in the social nature of human beings, in our willingness to collaborate and also in our willingness to sacrifice when maximization strategies prove to be dysfunctional. On this point, philosopher Richard Norman once suggested that the sacrificing of one’s interests to something like a shared common good need not be thought of as a sacrifice to something external:

Commitments to our friends or our children, or to causes in which we believe, may be a part of our deepest being, so that the experience of devoting ourselves to them is less like sacrifice and more like fulfilment.

(Norman 1983: 249, emphasis added)

p.197

Norman implies that the “deepest being” in each of us reaches for the same moral insight—and ultimately the same basis for conscience.

An example of comprehensive moral thinking

During 1983 and 1984, Velsicol Chemical Corporation, a Chicago-based producer of agricultural chemicals, proposed a “One World Communication System” for pesticide labeling. The idea was to create an industry-wide system of pictograms for agricultural workers in developing countries who were often illiterate or could not understand the precautionary information on conventional labels.

From the point of view of Velsicol’s stakeholders—customers, farm employees, local communities, and shareholders—the company’s labeling innovation was a success. But it was expensive, and a more comprehensive view seemed to call for more. Industry practices were not uniform and there were many hidden casualties in developing countries. A solution to this problem would require collaboration between industry (private sector) and government (US and host country public sectors). In the eyes of Velsicol, each had partial responsibility for solving the problem.

Unfortunately, enthusiasm for Velsicol’s pictogram initiative was not sufficient to move the idea forward, either at the National Agricultural Chemical Association (NACA) or at the US Environmental Protection Agency. The result was that Velsicol’s CEO was forced on economic grounds to discontinue the project (Goodpaster 1985). The company’s comprehensive moral thinking could have led to fewer lives lost to the misuse of these hazardous chemicals—a reflection of concern for human dignity and the global common good. The problem was not solved because coordination of corporate (and government) efforts was not achieved. Several executives at Velsicol, disheartened at this outcome, left the company.

The Velsicol case, of course, is an example of a company’s lack of success in influencing its industry association and its government. It also illustrates the distinction between a company’s categorical responsibility and its qualified (or conditional) responsibility for seeking comprehensive solutions. The very nature of comprehensive moral thinking—thinking outside what Heclo calls the internal morality of an institution—calls for collaborative efforts on the part of responsible institutions in several sectors. When efforts at collaboration are unsuccessful, then perhaps no further responsibility remains: “Ought categorically” implies “can”—but “ought conditionally” simply implies “must try.”

Implications for business education

Why were we so reluctant to try the lower path, the ambiguous trail? Perhaps because we did not have a leader who could reveal the greater purpose of the trip to us. For each of us the sadhu lives. What is the nature of our responsibility if we consider ourselves to be ethical persons? Perhaps it is to change the values of the group so that it can, with all its resources, take the other road.

(Bowen McCoy, “The Parable of the Sadhu,”

Harvard Business Review, 1983: 108)

Bowen McCoy suggests that one of the key roles of leadership lies in revealing the greater purpose of the trip and reminding the group of that greater purpose. Leadership is cultivated, in part, through education. So, in this concluding part, I offer thoughts as to how the discussions set forth in the previous sections might be employed to influence business education, and so ultimately the formation of future business leaders. There are at least three ways in which comprehensive moral thinking might influence business ethics pedagogy.

p.198

Challenging market logic and legal compliance

Business school faculty have an opportunity to go beyond “information transfer” and to challenge both “market value” and “legal requirement” as surrogates for corporate conscience. They can press students to search for criteria that go deeper. In so doing, students and faculty must take some risks as they come to terms with their often-unexpressed views about human well-being. Classroom debates can be encouraged about the sufficiency of both market incentives and compliance with legislation (such as, within the United States, Sarbanes–Oxley and Dodd–Frank) for preventing irresponsible business conduct in the realms of corporate governance and consumer financial protection. Faculty can use readings and case studies that encourage self-discovery for students, inviting them to go beyond market and legal measures of goodness, whether for customers, employees, shareholders (see, for example, the McGraw-Hill Create online database). Writing assignments can be given that call for an answer to the question: “What are the norms, beyond market effectiveness and legal compliance that I, as a future business leader, would be prepared to defend or reject for my company?”

For those who are apprehensive about encouraging students to “get normative” regarding economic and legal frameworks, it is useful to remember that when normative ethical judgments (about products and services, the dignity of work, the common good) are not addressed or defended with thoughtful reasons, they do not disappear. Rather, they “go underground” and become unexamined moral assumptions. We owe it to our students to assist them in their own leadership formation. Business leaders inevitably make moral judgments, but they need to be grounded in a solid understanding of the human person.7

Challenging the sufficiency of fiduciary and stakeholder thinking

The business ethics student should take seriously the imperatives of fiduciary shareholder and non-fiduciary stakeholder obligations while thinking more broadly about the societal contributions of economic, political, and civic institutions.

Students can be asked whether the Moorean question “This corporate decision most satisfies our shareholders and our other stakeholders, but is it right?” is an open question.

Analyzing business decisions solely in terms of their likely impact on specific categories of affected parties (“interest groups”) can miss morally relevant information. Much as the “Stockholder Proviso” warned us about reducing ethical decisions to fiduciary duties, the “Stakeholder Proviso” warns of another kind of reduction and invites more comprehensive moral thinking.

(Goodpaster 2010: 741, original emphasis)

As we noted previously, the word “comprehensive” signifies two things in this context: acknowledging the value of private sector collaboration with other societal institutions, and appreciating human dignity and the common good as overarching normative ideals that may exceed the reach of stakeholder satisfaction.

p.199

The bold idea of management as a profession

The third implication for business education may be the most straightforward and the most radical: challenging students to “reimagine” their careers in the vocabulary of professions, callings, even vocations.8 The best scholarly work on this topic was published in 2007 by Harvard Business School professor, Rakesh Khurana (see Khurana 2007). More recently, Khurana and Nitin Nohria have advocated eloquently for the professionalization of management (Khurana and Nohria 2008). Craig Smith and David Rönnegard comment:

Khurana and Nohria advocate making management a true profession, which would include the teaching of a formal body of knowledge and a commitment to a code of conduct. The latter, a “Hippocratic Oath for managers,” has inspired an MBA Oath movement, to which over 300 institutions have committed as of 2013. Khurana and Nohria (and the authors of the MBA Oath) are careful to frame their code such that it . . . emphasizes that corporate purpose has much to do with value creation. They write: “By turning managers into agents of society’s interest in thriving economic enterprises, we get out of the bind of viewing them as agents of one narrowly defined master (shareholders) or many masters (stakeholders).”

(Smith and Rönnegard 2014: 23)

A careful reading of the MBA Oath, included as an Appendix to this chapter, reveals a vision that respects not only fiduciary thinking and stakeholder thinking, but comprehensive moral thinking, e.g., “I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise” and “I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards.”9

But a caveat may be in order on this topic. As attractive as the idea of “management as a profession” may be, some would challenge it on the grounds that first, many skilled practitioners of management have no formal education in a technical body of knowledge, and, second, the idea of business managers enforcing something like the MBA Oath through a gatekeeping body may not comport well with our convictions about the importance of entrepreneurship. This being said, we should remember that the argument for the fiduciary relationship between managers and shareholders draws on an analogy between management and professions like law and medicine.

Concluding remarks

Nobel Laureate poet T.S. Eliot, in “Choruses from the Rock” (1934), observed that humankind is forever “dreaming of systems so perfect that no one will need to be good.” The power of this poetic phrase can be appreciated in the present context as we ask corporate leaders to think more comprehensively: to see that stakeholder and shareholder frameworks are ultimately meant to serve, not to supplant, the pursuit of human dignity and the common good. These frameworks reveal the need for a broader perspective from which the inevitable pushes and pulls of prima facie obligations can be negotiated. This perspective looks carefully at business as an institution—at the horizon of moral considerability and at society’s need for institutional collaboration. This perspective remembers why we create the systems (economic, political, and cultural) that we do, lest in Royce’s words, we “obscure the reality of our neighbor.”

p.200

Essential readings

The richness of the literature on the theme of stakeholder thinking (and its strengths and weaknesses) makes identifying “essential” readings difficult. However, taking into account the categories of shareholder thinking, stakeholder thinking, and comprehensive moral thinking, the following works prove, respectively, most essential. Alexei Marcoux’s article “A Fiduciary Argument against Stakeholder Theory,” (2003) offers a deeper level of understanding of the obligations of management to shareholders than most articles or books on the subject. And Goodpaster’s essay, “Business Ethics and Stakeholder Analysis” (1991), provides useful background to the subject of fiduciary duties. R. Edward Freeman’s Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (1984) is the source of a large literature in defense of stakeholder thinking (as well as a dissenting literature). And Joseph Heath’s article “Business Ethics Without Stakeholders” (2006) explains a plausible substitute for stakeholder thinking that deserves serious consideration. On the subject of comprehensive thinking, Hugh Heclo’s On Thinking Institutionally (2008) is indispensable. Finally, on the educational importance of comprehensive moral thinking and management as a profession, Rakesh Khurana’s book From Higher Aims to Hired Hands (2007) merits close attention.

For further reading in this volume on the legal personhood of corporations, see Chapter 14, The corporation: genesis, identity, agency. On the predominance of stakeholder theory in sub-Saharan Africa, see Chapter 37, Business ethics in Africa. For critical consideration of the compatibility of managerial responsibilities with duties to stakeholders, see Chapter 13, What is business? On the need for managers to have ethical awareness, see Chapter 27, The ethics of managers and employees. On the subject of business ethics education and on challenges to moral awareness, see Chapter 4, Teaching business ethics: current practice and future directions. On moral myopia and advertising, see Chapter 30, Ethical issues in marketing, advertising, and sales.

Notes

1 The reference to fiduciary duties to shareholders applies, of course, only to organizations that have shareholders. For other organizational forms, the definition of stakeholder thinking can be adjusted simply to “those who can affect or be affected by an organization’s decision making.”

2 Another measure of the significance and ubiquity of stakeholder thinking is that, as of August 2016, Google Scholar lists 629,000 books and articles since 1980 when searched under “stakeholder.”

3 It was also implicit in the work of (among other contemporary writers) Chester Barnard, The Functions of the Executive (1938).

4 This distinction appears in the literature in different ways. Interests may be taken as normative in relation to preferences. Alternatively, the truly valuable goods and services may be taken as normative in relation to goods and services that have market value.

5 “Reasonable” in relation to shareholder returns is here meant to signal the need for normative judgment about dividends or stock appreciation strategies that take seriously the health and resiliency of the corporation as a whole—in contrast to short-sighted “maximizing” behavior that could end up undermining the corporation. The 2015 scandal surrounding Volkswagen’s automobile emissions would be a case in point.

6 In the words of Benedict XVI in the encyclical Caritas in Veritate (2009) “In an increasingly globalized society, the common good and the effort to obtain it cannot fail to assume the dimensions of the whole human family, that is to say, the community of peoples and nations, in such a way as to shape the earthly city in unity and peace . . .” (§7).

7 Oxford philosopher Mary Midgley explains the vital productive role of moral judgment: “The power of moral judgement is, in fact . . . a necessity. When we judge something to be bad or good, better or worse than something else, we are taking it as an example to aim at or avoid. Without opinions of this sort, we would have no framework of comparison for our own policy, no chance of profiting by other people’s insights or mistakes. In this vacuum, we could form no judgments on our own actions” (Midgley 1981: 72, emphasis added). As one of the editors of this volume observed: “The choice isn’t between doing philosophy and not doing philosophy. It’s between doing philosophy badly and haphazardly to one’s detriment and doing it well and carefully to one’s good.”

p.201

8 Pope Francis, in his speech to the Joint Session of the US Congress, 24 September 2015, said: “Business is a noble vocation, directed to producing wealth and improving the world . . . especially if it sees the creation of jobs as an essential part of its service to the common good.”

9 Worth mentioning in this connection are the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (UNPRME). These principles, like the MBA Oath, reflect a comprehensive moral framework, and represent a “quasi-oath” not for individuals but for educational institutions.

References

Agle, B.R., T. Donaldson, R.E. Freeman, M.C. Jensen, R.K. Mitchell, and D.J. Wood (2008). “Dialogue: Toward Superior Stakeholder Theory,” Business Ethics Quarterly 18:2 (April), 153–190.

Barnard, C. (1938). The Functions of the Executive. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Berle, A. (1954). The 20th Century Capitalist Revolution. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, and World.

Boatright, J.R. (2006). “What’s Wrong—and What’s Right—with Stakeholder Management?” Journal of Private Enterprise 22:2 (Spring), 106–130.

Dodd, E.M. (1932). “For Whom are Corporate Managers Trustees?” Harvard Law Review 45:7, 1145–1163.

Donaldson, T. (2008). “Two Stories,” Part IV of “Dialogue: Toward Superior Stakeholder Theory,” (with B. R. Agle, T. Donaldson, R. E. Freeman, M. C. Jensen, R. K. Mitchell and D. J. Wood), Business Ethics Quarterly 18:2 (April), 153–190.

Donaldson, T. and L.E. Preston (1995). “The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications,” The Academy of Management Review 20:1 (January), 65–91.

Donaldson, T. and J.P. Walsh. (2015). “Toward a Theory of Business,” Research in Organizational Behavior 29:35, 181–207.

Drucker, P.F. (1978). “We Have Become a Society of Organizations,” Wall Street Journal, January 9 (Eastern edition).

Drucker, P.F. (1988). “Management and the World’s Work,” Harvard Business Review 66 (September), 65–76.

Drucker, P.F. (1994). “The Age of Social Transformation,” The Atlantic Monthly 274:5 (November 1994), 53–80.

Eliot, T.S. (1934). “Choruses from the Rock,” The Complete Poems and Plays 1909–1950. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Evan, W. and R.E. Freeman (1988). “A Stakeholder Theory of the Modern Corporation: Kantian Capitalism,” in Tom L. Beauchamp and Norman Bowie (eds), Ethical Theory and Business, 3rd edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 75–93.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Freeman, R.E. (2014). “Stakeholder Theory,” in the Encyclopedia of Management, 3rd edition. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 1–6.

Freeman, R.E. and D.L. Reed (1983). “Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance,” California Management Review 25:3, 88–106.

Freeman, R.E., J. Harrison, A. Wicks (2007). Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation, and Success. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gewirth, A. (1978). Reason and Morality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Goodpaster, K. (1978). “On Being Morally Considerable,” Journal of Philosophy 75 (June), 308–25.

Goodpaster, K. (1985a). “Toward an Integrated Approach to Business Ethics,” Thought 60:237 (June), 161–180.

Goodpaster, K. (1985b). “Velsicol Chemical Corporation (A),” HBS Case Services, 9-385-021.

Goodpaster, K. (1991). “Business Ethics and Stakeholder Analysis,” Business Ethics Quarterly 1:1 (January), 53–73.

Goodpaster, K. (2005). “Moral Projection, Principle of,” in C. Argyris, W. Starbuck and C.L. Cooper (eds), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Management, 2nd edition. Vol. 2. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 363–64.

Goodpaster, K. (2007a). Conscience and Corporate Culture. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

p.202

Goodpaster, K. (2007b). “Conscience,” in Robert W. Kolb (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society, Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 407–410.

Goodpaster, K. (2010). “Two Moral Provisos” Business Ethics Quarterly 20:4 (October), 741–42.

Goodpaster, K. (2011). “Goods That Are Truly Good and Services That Truly Serve: Reflections on Caritas in Veritate,” Journal of Business Ethics 100:1, 9–16.

Goodpaster, K. (2016). “Human Dignity and the Common Good: The Institutional Insight,” presented at the 40th Anniversary Conference for the Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University, July 24–26.

Goodpaster, K. and J. Matthews (1982). “Can a Corporation Have a Conscience?” Harvard Business Review 60:1 (May–June), 132–141.

Hasnas, J. (1998). “The Normative Theories of Business Ethics: A Guide for the Perplexed,” Business Ethics Quarterly 8:1 (January), 19–42.

Hasnas, J. (2013). “Whither Stakeholder Theory? A Guide for the Perplexed Revisited, Journal of Business Ethics 112, 47–57.

Heath, J. (2006). “Business Ethics Without Stakeholders,” Business Ethics Quarterly 16:4 (October), 533–557.

Heclo, H. (2008). On Thinking Institutionally. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Johnson, L. (2011). “Law and the History of Corporate Responsibility,” Minneapolis, MN: CEBC History of Corporate Responsibility Project Working Paper No. #6.

Khurana, R. (2007). From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Khurana, R. and N. Nohria (2008). “It’s Time to Make Management a True Profession,” Harvard Business Review 86 (October), 70–77.

Langtry, B. (1994). “Stakeholders and the Moral Responsibilities of Business,” Business Ethics Quarterly 4:4 (October), 431–443.

Mackey, J. and R. Sisodia (2013). Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Marcoux, A.M. (2003). “A Fiduciary Argument against Stakeholder Theory,” Business Ethics Quarterly 13:1 (January), 1–24.

McCoy, B. (1983). “The Parable of the Sadhu,” Harvard Business Review 75:3, 103–08.

Midgley, M. (1981). “On Trying Out One’s New Sword,” in Heart and Mind: The Varieties of Moral Experience. New York, NY: St Martin’s Press, 69–75.

Moore, G.E. (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagel, T. (1986). The View from Nowhere. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Naughton, M., J. Buckeye, K. Goodpaster and D. Maines (2015). Respect in Action: Applying Subsidiarity in Business. St. Paul, MN: UNIAPAC and University of St. Thomas. Available at: www.stthomas.edu/cathstudies/cst/research/publications/subsidiarity/.

Norman, R. (1983). The Moral Philosophers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norman, W. (2013). “Stakeholder Theory,” in Hugh LaFollette (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Ethics. London: Blackwell, 5002–5011.

Paine, L.S. (2003). Value Shift. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

Piaget, J. (1932). The Moral Judgment of the Child. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Pope Benedict XVI (2009). Charity in Truth: Caritas in Veritate, Encyclical Letter. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, §53.

Pope Francis (2015). “Speech to a Joint Session of the US Congress, 24 September,” Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Pope John Paul II (1991). Centesimus Annus: Encyclical Letter Addressed by the Supreme Pontiff John Paul II to His Venerable Brothers in the Episcopate, the Priests and Deacons, Families of Men and Women Religious, All the Christian Faithful and to All Men and Women of Good Will on the Hundredth Anniversary of Rerum Novarum. Sherbrooke, Quebec: Éditions Paulines, §36.

Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace (2012). Vocation of the Business Leader: A Reflection, 3rd edition St. Paul, MN: John A. Ryan Institute for Catholic Social Thought.

Ross, W.D. (1988) [1930]. The Right and the Good. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Royce, J. (1865). The Religious Aspect of Philosophy, reprinted 1965. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in Administration. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Smith, N.C. and D. Rönnegard (2014). “Shareholder Primacy, Corporate Social Responsibility, and the Role of Business Schools,” Journal of Business Ethics 16 (November), 1–42.

Stone, C.D. (1991). Where the Law Ends: The Social Control of Corporate Behavior. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

p.203

As a business leader I recognize my role in society.

• My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

• My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow.

Therefore, I promise that:

• I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

• I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

• I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

• I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

• I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

• I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

• I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards.

This oath I make freely, and upon my honor.