4

Trend Following: Cut Your Losses and Let Your Winners Run

British-born David Ricardo (1772–1823) is one of my personal heroes and a brilliant classical economist who had a huge impact not just on me but on the world. Let me share a bit of his story and you will understand why.

Ricardo descended from a family of prominent Sephardic Jews who were expelled by the Catholic church in Portugal and settled in Holland. His Dutch-born father, Abraham, moved his family to London (where Ricardo would later be born) and became a very successful stockbroker on the London Exchange and leader of the Jewish community in London. As a teenager, the young Ricardo began working at his father’s side learning the trade, but he was an independent thinker and not always on board with his father’s traditional ways. At age 21, Ricardo eloped with Priscilla Ann Wilkinson, a Quaker, and the young couple became members of the Unitarian Church. He broke ties with his family and went off on his own with barely any funds. Because of his good reputation, he was able to start his own business in the markets with the support of an eminent bank house. Ricardo made his living in the markets and did really well. But his passion was the world of ideas. He studied economics and math and by his late thirties began publishing his views on free trade (he was a staunch believer) and wages, currency, labor theory, political economy, and the law of diminishing returns. Along with John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith, and Robert Malthus, he helped create modern economic theory and influenced generations to come.

In his own time, his reputation largely rested on a single bet, for which a lifetime of trading and speculating had been merely a dress rehearsal. In 1815, Riccardo bought British government bonds at rock-bottom prices, betting on the outcome of the Napoleonic Wars (legend has it that he did so with advanced knowledge, but this is unclear). When word got back from Belgium that the Duke of Wellington had beat Napoleon at Waterloo, British securities soared, and practically overnight Ricardo became one of the richest men in Europe, with a million in sterling, which would be in the region of 80 million British pounds today.

After Ricardo’s death, a British newspaper editor named James Grant described the secret of Ricardo’s success:

Mr. Ricardo amassed his immense fortune by a scrupulous attention to what he called his three golden rules, the observance of which he used to press on his private friends. These were, “(1) Never refuse an option when you can get it; (2) cut short your losses and (3) Let your profits run on.”

By cutting short one’s losses, Mr. Ricardo meant that when a member had made a purchase of stock, and prices were falling, he ought to sell it immediately.

And by letting one’s profits run on he meant that when a member possessed stock, and prices were rising, he ought not to sell until prices had reached their highest and were beginning again to fall.

I have now shared with you three of the cornerstones of my approach to trading and life: Get in the game. If you lose all your chips, you can’t bet. Know, and improve, the odds.

But the fourth is the most important. It is Ricardo’s Rule, for which I have named this book: Cut your losses, and let your winnings run. Put simply: When something is not going well, stop doing it. When something is going well, continue. This rule is at the core of my trend following approach to trading. I quote it nearly every day. If you prefer country music, you can quote the legendary song “The Gambler”: “You’ve got to know when to hold’em, know when to fold’em, . . .”

Here’s how it works: To spot a rising trend, you look at where the price is now relative to where it has been. So for example, if the price of a commodity or stock is higher than it has been for 40 or 50 days, more people believe it is higher, so you can buy and ride this trend. When to get out? I simply ask myself how much can I afford to lose? If the answer is 2 percent, for example, then as soon as the price comes down by 2 percent, it is gone from my portfolio. That’s how much I’m willing to risk. In other words, cut your losses quickly and stay with your winners. This is what makes you money.

STATISTICS RULE

Let me be clear: I did not invent trend following. There were trend followers before Ricardo, and trend followers after him. Richard Donchian, for example, is sometimes called the father of modern trend following. He was a trader who graduated from Yale and MIT and noticed that commodity prices often moved in trends, meaning that if something went up or down, it would likely continue in that direction for at least a little while. In the 1960s, he started writing a weekly newsletter called Commodity Trend Time, publicizing his “four-week rule,” strategy. He bought when prices reached a new four-week high and sold when they reached a new four-week low.

So it is not that trend following wasn’t out there. It was. But my partners and I were among the first to automate it by creating a systematic approach based on data and using backtesting. In other words, we proved it worked using the scientific method. We also had great timing. The emergence of increasingly powerful computers during the 1970s that we could actually access made systematic research possible. In fact, a trader I know, Ed Seykota, was one of the first to create computerized trend following trading and he was using punch cards at first!

But I always say: I was driven not so much by greed as by laziness. I wanted money to work for me, not the reverse. My goal was to create a system I could put on autopilot so I didn’t have to anguish myself over the ups and downs of the market. This way I could sleep at night, and even better, make money while I was sleeping. I did not do this because I was arrogant—quite the contrary. Having failed at so many things in my childhood and youth, I always presumed my own wrongness and limitations. To get around this human fallibility, I wanted instead a rigorously tested statistical approach that was proven on large numbers. I explained it this way to Jack Schwager when he interviewed me for his book Market Wizards:

What makes this business so fabulous is that, while you may not know what will happen tomorrow, you can have a very good idea what will happen over the long run.

The insurance business provides a perfect analogy. Take 1 sixty-year-old guy and you have absolutely no idea what the odds are that he will be alive one year later. However, if you take 100,000 sixty-year-olds, you can get an excellent estimate of how many of them will be alive one year later. We do the same thing; we let the law of large numbers work for us. In a sense, we are trading actuaries.

Trend following isn’t a strategy solely for commodity markets or futures; you can use it for stock trading as well. Recently, a friend told me he was buying a major chunk of Microsoft stock, and he was doing it from a trend following point of view. We discussed how Microsoft now leads the cloud server market with overall year-to-year growth of more than 50 percent. A recent fiscal year just ended showed 100 percent growth. As of my final review of these pages in late February 2019, Microsoft is still trading near its 52-week high of 116 dollars per share. In 2018, the S&P 500 index as a whole lost 6.2 percent.

That is certainly a very strong trend, and there are many possible explanations for this strong performance. To name a few: Microsoft aggressively invested as the leader in enterprise cloud technology, which is now a booming business. A strong CEO has been at the helm for some years. And, the company still has its lucrative model of licensing outside partners. These factors are certainly influential and interesting. But the underlying fundamentals of a company are not what motivate me, a trend follower. A trend follower will buy Microsoft stock because the stock price is rising and has been rising long enough to establish that there is a trend in place. The trend follower will not try to predict how long it will last. When the trend falls, he or she will get out. In other words, I don’t make money because I know anything. I only make money because I do what the market tells me to do. See, I prefer averages, kind of like a bookie, with my risk spread far and wide so that no single trade is too emotional. I like my workplace to be boring (screaming at a monitor was never something I wanted).

In the world of trading, some traders analyze the nonstop avalanche of market data using various software packages to make numerous trades on a day-to-day, hour-to-hour basis, exploiting micro swings in the markets and hedging losses. Some of these techniques can work if backed by the biggest banks and huge staffs. But too often traders get so caught up in their charts and never-ending data sets that they lose touch with the big-picture opportunities staring right back at them. I don’t need a million charts or thousands of pieces of fundamental data to tell me that Microsoft’s cloud business is booming—the trend is telling me. It’s telling you too.

Look, I respect the sheer intelligence and devotion of economists and historians who have attempted to understand global markets and develop a unifying theory of human behavior and market dynamics. But I don’t believe any such theory will hold up to scrutiny in the real world of money on the line.

When you start believing you have remarkable market predicting powers, you get into trouble every single time. To repeat myself, I’ve always built an assumption of wrongness into my trading, and this should be a mandatory practice in your own financial life too. Keep asking, “What is the worst thing that can happen in this scenario?” Then the worst-case scenario is my baseline. We always want to know what we are risking, and how much we can lose.

Interestingly, trend followers have tended to do well during times of crisis. Why? Because big sell-offs create dramatic trends across all markets. As my friend Michael Covel discusses in his book Trend Following:

For markets to move in tandem, there has to be a common perception or consensus about economic conditions that drives it. When a major event occurs in the middle of such a consensus, such as the Russian debt default of August 1998, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, or the corporate accounting scandals of 2002 [and the 2008 equity market crash], it will often accelerate existing trends already in place . . . events do not happen in a vacuum. . . . This is the reason trend following rarely gets caught on the wrong side of an event.

With the help of modern automation, systemizing my rules, I move quickly and don’t wait for the markets to drop 50 percent, and thereby lose more than I can afford to. I get out, preserve my capital, and look forward to the next rising opportunity, because there is always a next one coming.

BUT WHAT ABOUT BUY AND HOLD?

What I am describing is quite different from Wall Street’s conventional advice, which tells investors to buy and hold with a passive approach to their portfolios. In this school of thought, you should do nothing when prices drop. The idea is not to pay attention to fluctuations in the market, but rather wait it out, because over time, the stock market always rises and you always do well.

This buy-and-hold approach is based on the efficient markets theory that markets are rational because everybody has access to the same information, and prices adjust accordingly to their right value. Put simply: The market always wins. Therefore, mere mortals cannot pick stocks that will do any better than the S&P average.

I’ve bought low and sold high in my life, and I believe, unequivocally, that when this approach succeeds, it is a happy accident. Why? Because no one can know for sure that a property or stock or whatever market or life endeavor will eventually rise and when. Yes, you might do very well with a buy-and-hold strategy. But you also may have to endure booms and busts and potentially major losses for lengthy periods—losses many people may not be able to tolerate. For example, looking at the historic S&P Index, it’s clear that if you had money in an S&P Indexed fund in the early 1950s and withdrew it in the early 1970s, your buy-and-hold strategy would have worked brilliantly because the market was soaring when you exited. But what if you didn’t want (or need) to take it out until April of 1982? You would have been heartbroken because the S&P had dropped again dramatically.

Never, ever forget that no one can predict the future. History is littered with successful companies that unexpectedly fell beneath the weight of time and change. I remember when Enron was the company of the future. Where did Enron wind up? No matter what anyone says, you shouldn’t believe they know what will happen economically or in the markets years from now. To speculate this way is dangerous. We live in a hyper-growth high-tech entrepreneurial economy where industries rise and fall in less than a decade. The profession of setting type by hand had been around for hundreds of years, passed down for generations. Then the computer arrived and digital typesetting wiped out the profession in just a few years.

Another great example? Uber has only been here since 2009 and it is now worth about 60 billion dollars. Uber, Lyft, and Grab have crushed the taxi and limousine industry worldwide. I’ll bet that before 2009 every Uber stockholder who was not from the company never thought for a minute that yellow cabs could become as outmoded as a horse and buggy.

Consider the telephone. When my older daughter was a teenager, I knew who she was going out with because the phone would ring, and we’d answer and ask who it was. Then we called her to the phone, which back then was something that came out of the wall. Three years later, I had no idea who my younger daughter was dating, because email had arrived and that’s how she arranged her social life and dates. Today, if they both weren’t married, they might use Tinder, which arrived in 2012 and became the instant dating software of choice for adults of all ages by eliminating the fear of rejection from meeting potential dates through its double opt-in navigation. The app’s parent, Match Group, was recently valued at $3 billion (2017). When was the last time a young person called another young person and “asked them out” on a date? Tinder’s swiping interface will, I am sure, spread in different forms to job searching and other areas I can’t predict. And I’m sure that at some point it will be replaced by something else. We live in a throwaway society and in that kind of world . . . my rule is sound.

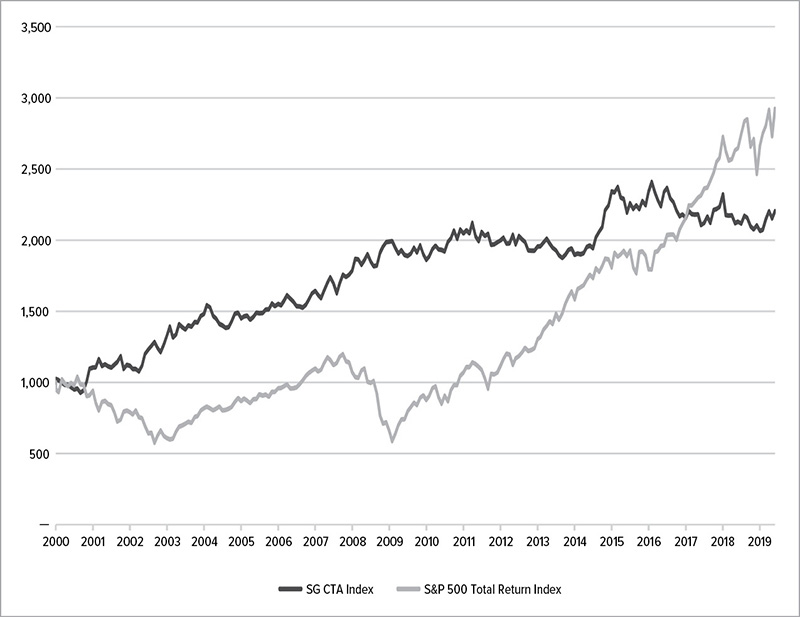

FIGURE 4.1 Trend Following Compared to Buy and Hold

Trend following (Societe Generale’s the SG CTA Index) compared to equity markets (the S&P 500 Total Return Index) from January 2000 to June 2019.

Source: Alex Greyserman and Kathryn M. Kaminski.

I am not saying that you should not strive to buy low and sell high. Nor am I saying that the buy-and-hold approach is wrong. There is no single trading or investment approach that works every time. This is why it is best to mix and diversify. Back when we started, trend following was radical, because people thought you must use fundamental information to make market decisions. A quant method such as trend following, which just used price to buy and sell, was sacrilege. Trend following is about odds, and Wall Street is about telling stories and making predictions (people sadly pay a lot for predictions). So not surprisingly many advisors still push buy-and-hold asset investing to the exclusion of other approaches, but it is now possible to diversify because today there are mutual funds and exchange traded funds (EFTs) that allow ordinary people to gain exposure to trend following approaches that complement their traditional portfolios.

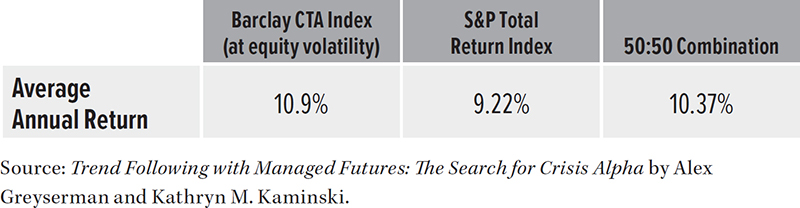

In a study that compared average annual growth, my colleague Alex Greyserman and his coauthor Kathryn Kaminski found that during this 20-year period between 1992 and 2013, trend following outperformed (as measured by the Barclay CTA Index) equities (as measured by the S&P Total Return Index). Most revealing is that if you had combined both approaches equally, you would have done best of all.

TREND FOLLOWING FOR LIFE

The Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) wrote that “one must never forget that every action is embedded in the flux of time and therefore involves a speculation.”

I agree. Life is a constant series of bets that we must make every day in the face of uncertainty. In life, as in the markets, we are wise to admit what we do not know. We can use only the observable facts at hand as we make decisions, knowing that we can be wrong.

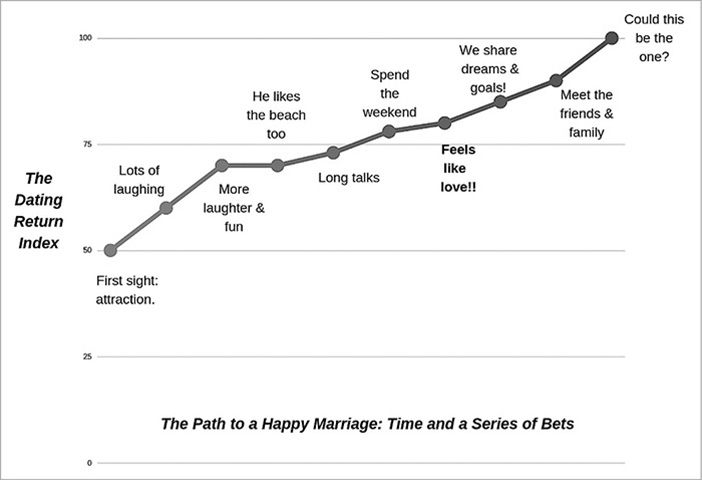

Humans are not rational in markets or life. For example, we all know that to lose weight we should just eat less and move more. So why don’t people do it? I like to use love and dating as examples when I try to help people understand my ideas. Far more people are experienced with the quest for love than they are with the quest for a fortune. We all can relate to the power of attraction, the pursuit, and the joy of finding a partner, as well as the disappointments of losing at love. After all, we humans are, above all, wired to procreate, which is why the drive to pursue romantic partners is very strong.

There is something quite comparable in money and love, and that is risk. When we give ourselves to someone, it is a big risk in exchange for a big gain—or so we hope. Usually we do not stay in a relationship unless we are receiving something positive. How long do we stick with a bad trend early in a relationship? Not long? What about 20 years down the road with a shared home and children? How do you manage your risk? It gets complicated fast.

Let’s look at my basic method again, and I’ll show you what I mean.

1. Get in the game. You know sure as hell that your future spouse is not going to show up and knock on your door. The odds are perhaps one in a billion. You know you must get out there, so you spiff up your looks, put on lipstick or shine your shoes, and off you go to the dance, the bar, the party, church, or work—wherever the game is being played. (In the case of Tinder, you take a good selfie and put yourself out there with a brilliant description. Yes, you are in the game.)

2. Set clear goals. Brilliant conversation or a good sense of humor? Sex with no strings attached? Marriage potential? A head turner? A big earner? Someone in your same religion or race? You know what you want. Of course, you’ve set goals for what you are looking for in a partner. If you haven’t thought through these issues you are asking for trouble.

3. Minimize your risk. Would you take a date to see the most expensive show and eat at the most expensive restaurant in town on the first date? Probably not. But would you go out for coffee or drinks or Chinese food with many promising candidates until you find the one who sets off a spark? Definitely. And you will most certainly use game theory by controlling the timing of your bets. Game theory uses observable facts to determine probability, right? So, if there is no one who meets your goals, you’d rather “sit this one out,” rather than investing good time and money on a date you already know is going to be a dud, right? This is a clarifying way of thinking for many of life’s confusing situations.

4. Cut your losses quickly, and let your winnings run. You will give marriage vast amounts of time, money, and energy—despite the odds that the chances of divorce are fifty-fifty. Early on especially, it’s important that you don’t drain your resources on bad bets.

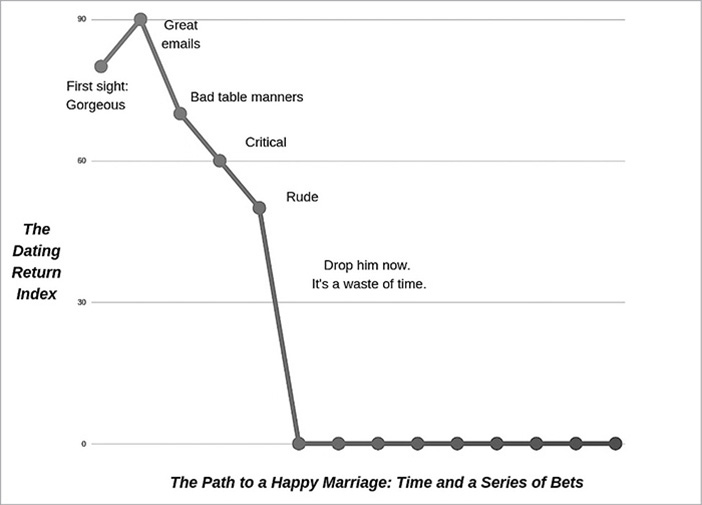

LOVE AND TREND FOLLOWING: THE PATH TO MARRIAGE AS A SERIES OF BETS

Where would you place your bets in each of these scenarios?

FIGURE 4.2 Love and Trend Following: Run with Your Wins

FIGURE 4.3 Love and Trend Following: Cut Your Losers

Sometimes you meet a potential partner who seems so wonderful. The trend goes up and up and up, and for some reason, this freaks you out, and you cut and run. Ask yourself why you are jumping off of a good trend. Do you think life can’t be that good? Do you think you do not deserve for it be that good?

In my first marriage, the trend went up from the start and it was a happy marriage. As I mentioned, my wife Sybil and I came from very different backgrounds. In my second marriage, I chose someone who had a very similar background to mine. Sharon is from Brooklyn and, like me, came from nothing but made a decision she wanted a better life. She was also friend of Sybil’s. Because we had so much in common, there was so much that she understood that I didn’t need to explain. Marriage is one of life’s biggest bets. On each marriage, I asked myself, do I want to spend time with this person? There is so much you have to do with your spouse. Having a great time in bed is chemistry. Having a marriage is life. You decide what you want to count as worthwhile.

See where I am going? Let your winners run. Getting into and staying in a good relationship is much easier than getting out of one. When do we cut losses in a marriage? A friendship? A business? Just as with money, you must ask yourself how much money you are willing to lose. So many fortunes have been lost in history by sticking with bad ideas. So many people stay in bad situations waiting it out despite all evidence that the trend is sinking. People start a business and hang on for 5 or 10 years despite poor returns.

Years ago, a young woman I had known since childhood told me her growing fear about going to work every morning at the high school she taught at in the Bronx. We were walking on the beach one day when she told me what she really wanted to do was be a therapist.

“Why aren’t you?” I asked.

“I don’t want to give up my pension.”

But then she went on to describe a horrifying event. A few weeks earlier, a student upset about failing a course walked up to a colleague of hers, a fellow teacher, and shot the teacher point-blank in the face.

“Wait,” I said. “You’re telling me you are working in a place where one kid can shoot another or shoot you, and you don’t want to leave because of a pension?” What is a pension compared to the risk of getting shot? It’s a bad trade. First of all, there is no guarantee you are going to get the pension—because so many things can happen between now and then. And you can get shot and lose your life risking it daily to keep the supposedly “safe” job rather than pursue her lifelong passion of earning a graduate degree in clinical psychology.

Thankfully she came to see she needed to cut her losses by following the rule. She quit the job, went to school, and went on to have a successful career as a psychologist.

People find it so difficult to walk away from sunk costs. If you stay too focused too long on a bad bet, you are going to miss better opportunities. This can be said for the markets as well as in life.

In the same way, don’t buy into the myth that walking away makes you a quitter. If you’re running for US president and trailing badly in the primaries, don’t hang around to show you’re the real thing when you can’t possibly win and do stupid stuff that only makes the rest of your life miserable. Remember your goal: You want to be US president. Come back in four years with a better plan.

Remember, there are so many things we cannot control in life and markets. But you do have control over the choices you make. And you can make a conscious decision about how much you are willing to lose. I take you back to the initial questions: Who are you? What do you want? With a trend following mindset, you empower yourself to see with clarity that you can make the right choice for right now. Trend following gives any motivated person a chance to invest in the markets with managed risk.