Why Your Customers Want You to Be Good, and What You Can Do About It

The last week of May into the first week of June 2020, similar images kept popping up in my social media feed. Major companies were tweeting out images of white text on all-black backgrounds. As I kept scrolling, more kept popping up: Amazon, Disney, TikTok, the NFL, Marvel. Even video game companies like EA Sports and PlayStation had their own versions.

These white text/black background images were, of course, responses to the murder of George Floyd and in support of racial justice. The collective despair and anguish that we all felt while watching the 8-minute, 46-second video of Floyd’s death shocked this country into an uprising not seen in a generation. People place a lot of trust in companies, and, as a result, expect more from them. They want the companies and brands they support to authentically engage with social causes and create equitable impact. Companies could not choose to be silent on this issue as millions of people (and potential customers) took to the streets protesting the systemic racism Black people and people of color face each day. In the social media age, companies large and small quickly shared their thoughts and responses, with many also pledging dollars to racial justice charities.

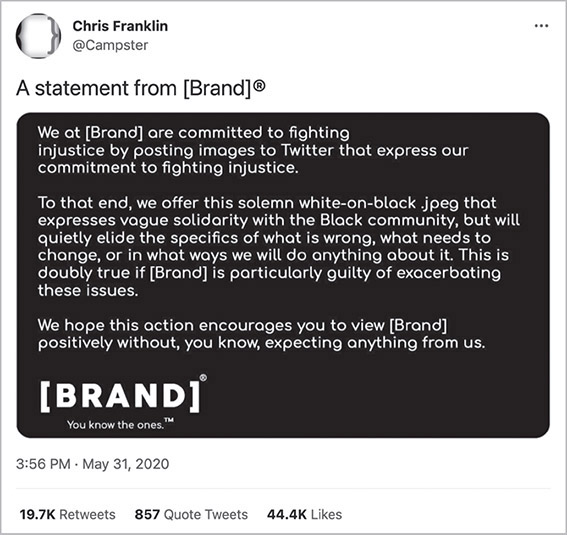

But while social media allowed companies to connect quickly with people during this emotionally charged time, the digital nature of the communication allowed consumers to connect right back with them. Many people saw these statements as hollow and nothing more than a PR opportunity with a little money thrown in for good measure.1 The statements became so ubiquitous and mocked that one Twitter user created a standard [Brand] response template (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 A standard [brand] response

Like many things on social media the outcry in response to these statements quickly ebbed. But some of these statements of support were met with more than an eye roll and snark. There were real consequences, with some companies’ statements being called out as hypocritical in light of past decisions that were seen as racist.

When the beauty company L’Oréal released a statement in support of the Black community and encouraged their customers to speak out against racism, the model Munroe Bergdorf shared that when working on a L’Oréal campaign in 2017 she was fired because she spoke out about white privilege after the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville that left a counter-protestor dead. In her response to L’Oréal’s statement in solidarity with the racial justice protests in 2020, she said:

I had to fend for myself being torn apart by the world’s press because YOU didn’t want to talk about racism. You do NOT get to do this. This is NOT okay, not even in the slightest. . . . Where was my support when I spoke out?

A company’s reputation and brand value were not the only things that suffered in the backlash to some of their statements. The most notable example occurred at the food magazine Bon Appétit, whose editor-in-chief resigned in June 2020 when current and former employees raised allegations of racial discrimination and a toxic work environment. Several other senior-level departures followed, and the magazine had to pause and rebuild one of their most popular revenue streams, their YouTube channel, which had over six million followers and was one of the largest video outlets for parent company Condé Nast. Many of their biggest stars refused to continue to work with Bon Appétit because of its unfair treatment of people of color.2

Nevertheless, the deluge of corporate statements in response to the death of George Floyd were an encouraging step forward and represented a shift in our culture. The NFL went from banning players for kneeling during the national anthem to protest police brutality3 to releasing a statement that included the words “black lives matter.” But, the callouts and accusations of inauthenticity also showed that companies needed not only to think more about and be better at navigating the current social landscape, but to do more not just when something happened that caused a public outcry.

Many companies did, though, “walk the walk” and followed through on the commitments they made in the summer of 2020. Citibank, for example, made a $1 billion commitment toward closing the gap in wealth between Black people and white people—which by some measures is a 10 times difference on average between the races4—and committed to deploying these funds to increase homeownership rates, support Black businesses, and partner with nonprofits working on racial equity. As of the fall of 2021, Citi was meeting or exceeding their goals,5 leveraging some of the strategies outlined in this book, such as using procurement dollars to support Black-owned business suppliers.

Citibank and the other examples I’ll share show that engaging with social causes can no longer end with a company sending out a statement and donating some money. Customers expect that what you say is consistent with what you do and who you are as a company. That means it’ll take a lot more work to meet the needs of those customers than simply putting some words on a black background every time something major happens around the world.

WHY YOUR COMPANY SHOULD CARE (OR THE BUSINESS OF BUSINESS IS NOT JUST BUSINESS)

At this point, you are probably saying to yourself—OK lady, I hear you, but didn’t these same companies post record profits in 2020?6 Seems like they are doing something right.

And you would be correct. Many of these companies did exceedingly well during the aftermath of George Floyd’s death (and the height of the pandemic), and continue to do well. PR fiascos come and go, and companies putting their feet in their mouths isn’t anything new to this century.

But dismissing the challenges companies had navigating the events of the summer of 2020 ignores a broader trend in customer behavior that companies cannot afford to dismiss. People place a lot of trust in companies, and expect more because of it. The Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual survey of trust and credibility, shows that despite the economic turmoil of the past few decades, trust in business has only continued to rise, and now businesses are more trusted than both government and nonprofits (referred to as NGOs or “nongovernmental organizations”). Trust in businesses has grown in the age 35–64 demographic by 17 percentage points since 2007, and in 2018, for the first time, businesses were more trusted than NGOs.7

But this trust also comes with expectations from customers. Almost 90 percent of Edelman survey respondents said that all stakeholders—customers, employees, and communities—are most important to a company’s long-term success. Only a little more than 10 percent say that shareholders are the most important thing. Over 70 percent agree that “a company can take specific actions that both increase profits and improve the economic and social conditions in which it operates.”8

These trends are even more apparent in the growing-in-influence millennial population. Millennials were 1.5 times more likely to purchase a product from a “sustainable” brand, and twice as likely to look for a job at a sustainably minded company.9 Over 70 percent of millennials say that giving back and being civically engaged are their highest priorities.10

Women, too, tend to be more focused on companies who are doing well BY doing good. Research on sustainable investing conducted by Morgan Stanley found that around 80 percent of women say they are interested in socially responsible investing, and 56 percent were interested in their investments having a positive impact, compared to 45 percent of men.11

And these consumers can smell BS too. Anything hypocritical will be called out. Authenticity is more important than anything else. Consumer research has shown that up to 90 percent of consumers say that authenticity is an important factor in determining which brands they like and support,12 and companies that improve their reputations can increase their sales by up to three times.13

A focus on social causes and social impact adds up to an increased customer base and additional profits: Research from Neilsen found that two-thirds of consumers say they prefer to buy from companies that create social impact, and nearly half say they are willing to pay more to do so.14

Despite some of the corporate missteps in the wake of George Floyd’s murder—and the backlash that came from both the political left and the right—consumers have actually doubled-down on their expectations for companies since 2020. In their 2021 survey, Edelman found that businesses have much more to gain than lose by taking a stand on racial injustice. Over 80 percent of consumers say a company would gain or earn their trust by doing so, a four-percentage-point increase from 2020. In 2021, there was a 20 percent increase in the number of people who said they would start or stop using a brand based on a company’s response to the racial justice protests. These increases were most pronounced among younger consumers.15

Given all this, and with all due respect to Milton Friedman, it is clear that the business of business is not just business. A focus only on profit maximization is not what your customers want, and continuing that shareholder-driven approach is costing you customers and revenue.

CAPITALISM’S “HOLY TRINITY”: CREATING EQUITABLE IMPACT

Our country was founded on the belief that “all men are created equal.” Yet, not every American was included. Not even every American man was included. What ultimately was most dangerous about the dichotomy between the ideals of our country’s founding—as understood then—and the reality of the laws the founders put in place—as they were applied over time—is that it led to a belief in a fair system where everyone had the ability to win. This belief held despite not everyone being able to participate in, much less compete in, what became our American capitalist system. And with each generation, Americans of means pass on a belief to their children that they are winning because they earned it, because they worked hard, because they fought the good fight. What they do not acknowledge is that generation after generation they have had a head start through unfair accumulation of wealth that assures them victory.

It is easy to think rigging the fight was only a problem in the early days of American capitalism. But that’s not so. Coupled with continued racist policies, the capitalist system has been rigged against working people and especially people of color since the country began up to and including now. The most egregious failure of American capitalism was slavery, which many of the country’s founders believed was not only an economic necessity, but righteous. Others accepted this view without question. Its legacy is felt today. Enslaved Americans did not have the freedom to benefit from the goods they produced nor the resulting profit—up to $59 trillion by some estimates.17 Even after slavery was abolished, the country moved on to Jim Crow, then redlining, and on to the GI Bill and the Social Security Act, which also deliberately excluded people of color. More recently, the Federal Highway Act and Urban Renewal calculatedly destroyed Black communities, and predatory loans and mortgages were explicitly targeted at Black and brown people.

From day one, American capitalism violated the very tenets of freedom and opportunity espoused by the system. And the results show: according to Opportunity Insights, a nonpartisan, not-for-profit organization based at Harvard University, if you are born in the United States, your zip code is a greater predictor of your success than your substance, particularly if you are a person of color.18

But despite these failings, capitalism as an economic system is not inherently good or evil. It is just a tool for organizing a society and culture. What is more important than the tool is the people and how and why they wielded that tool. Historically, despite our country’s ideals, the underlying belief of those in power in human inferiority has undermined the system and justified unfair practices.

It doesn’t have to continue that way. The promise of our country and the freedom that we espouse has consistently attracted dreamers, problem solvers, hard workers, and all manner of geniuses from across the globe. Our ideals have inspired people from all backgrounds to bring their talents to our shores and often transform our country and the world for the better.

American companies represent 80 percent19 of the world’s top companies as defined by market capitalization. In addition, over half of the Fortune top 25 best global companies to work for are headquartered in the United States.20 And perhaps, unsurprisingly, several companies appear on both lists. Most people tout market capitalization as the ultimate indicator of economic health, but the most recent financial downturns show that profit at the expense of people and the planet have longstanding negative externalities which are now amplified due to our global interconnectedness—such as financial products leading to market instability or a disregard of the social costs of carbon dioxide production leading to increased pollution. However, the fact that so many US companies are considered great places to work is an indicator that these organizations have the raw material in place to aspire to the next level of shared prosperity.

Central to this shared prosperity is an investment in our common infrastructure, both physical and social. Many people hear “American capitalism” and think “make as much money as you can no matter the cost,” but that idea is relatively recent. Immediately after World War II, companies were more likely to invest in infrastructure, talent, education, and other resources that all communities and businesses benefited from—there was little difference between prosperity of a business and the communities it worked in. According to professors Jan Rivken and Michael Porter, as globalization trends separated a business’s location from its workforce, a disconnect between business and communities developed and led to divestment in collective resources.21

We now see that investments in physical and social capital are not “nice-to-have” measures; instead, many are the very factors that drive economic resilience. Although there is more work to be done to address the oftentimes crumbling infrastructure in the United States (both human and physical), American capitalism has a longstanding culture of looking to stabilize environments to create the enabling conditions required to facilitate resilient commerce.

Despite the many challenges to our economic approach, American capitalism works well for those for whom it works. So the question is: How do we both harness the strength of our current approach and acknowledge historical and existing inequity to help businesses access their full potential and help strengthen our American capitalist system? How do we help businesses create what I call “equitable impact”?

We have to get back to that pre–World War II approach to capitalism with what I call the “holy trinity of capitalism.” This trinity is comprised of (1) a business owner, who creates something of value, (2) a customer, who pays for that value, and (3) businesses, that hire employees to produce that value in exchange for a livable wage and a quality standard of living. That holy trinity has been disrupted over the years, as people focused more on profit maximization, cutting costs by reducing wages and benefits paid to employees, and cutting the quality of the products and services delivered to the customer. The result: cheaper goods of lower quality and full-time employees who must rely on government assistance to make ends meet.

To restore the holy trinity of capitalism, we have to get back to the true meaning of “value.” Often the theoretical idea of “value” in business is shorthanded as “profit.” This makes sense in some ways, if someone is willing to pay you more for a product or service than what you put into it assumes you have added value to whatever you are selling. Sometimes, it is that simple. But on a broader, economic scale, equating profit with value is deeply flawed. At the beginning of the chapter, I discussed corporations whose stock prices rose during the pandemic, increasing profits for their shareholders. It would be hard to argue that the overall value added to the country by these companies was equivalent to the increase in their stock prices during a time of great suffering and pain.

My friend and colleague Jay Coen Gilbert has focused his post–AND 1 career on this idea of redefining what corporate value creation should be (see his Foreword for more detail). Rather than focusing on short-term profit for shareholders, we have to think about total value-add for all stakeholders—from the quality of life of workers to the health of customers and the well-being of the people living in our neighborhoods and communities. Some of this value creation is measurable—such as the health of people in a community, or the ability of employees to afford rent and groceries—but some of it is intangible; for example, whether or not a company is being a good partner in creating a better life for everyone it touches. Jay believes, as do I, that this stakeholder-not-shareholder perspective on business is actually aligned with the core fundamentals of our democratic capitalist system.

Larry Fink, the CEO of the massive investment management company BlackRock, also agrees. In his 2022 annual letter to all CEOs of companies in which BlackRock invests, he said:

Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not “woke.” It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper. This is the power of capitalism.22

Instead of focusing on profit and shareholders, we must consider all stakeholders and the value transfer that happens at all levels of a company’s behavior, not just at the point of sale between customer and business. This broader consideration of how a business is creating value will expand your priorities as a business owner or employee, and help ground your work in that holy trinity of what capitalism should be—creating impact that benefits all stakeholders in an equitable way. It will create a virtuous cycle of value-add activities that will help your employees and contractors have a quality standard of living and your customers have an enjoyable experience—while maximizing your profits. Leveraging capitalism in this way can create equitable impact that benefits all; in fact, it is so essential to how I do business that I named my company after it: CapEQ, a mash-up of capitalism and equitable impact.

So, maybe our good friend Milton Friedman wasn’t wrong, just a little off: the business of business IS business, we just need to rethink how we do business and what we can achieve with the tools of capitalism. We need to refocus on true value-generation and increasing overall well-being instead of profit maximization, and not get distracted by the “winner take all” mentality we have now. Achieving the true potential for your business, and all businesses, requires us to shift our mindset to think about profit and value in this way.

FINDING AUTHENTICITY WITH THE EQUITABLE IMPACT VENN DIAGRAM

Easier said than done, right? Taking these steps is hard work, but necessary. With this changing sociopolitical environment, businesses ignore engaging in social causes at their peril. Sooner or later, they will be pulled into some social discourse, either by their consumers or their employees. The past few years—with our increasingly fraught political environment around racial justice, climate change, voting rights, and other activist causes—show that companies need to be prepared.

We know that inauthentic, performative, one-time statements aren’t enough. This work needs to be embedded across a company, encompassing all stakeholders, including the broader community. These changes need to be long-term and sustained.

For example, the Dove “Campaign for Real Beauty” turned traditional beauty advertising on its head to highlight “real” women and their bodies rather than photoshopped models representing unrealistic standards of beauty. The campaign began in 2004 and has been massively successful (I am sure you have seen some of the ads), helping to shift industry standards, elevate different types of beauty, and increase engagement with customers in an authentic way. The Campaign for Real Beauty was one of the first ad campaigns that benefited from social media and the desire of people to share the content themselves because it aligned with their identity and values.23

Nevertheless, this campaign and the broader body positive movement has received some sustained criticism. Namely, as the writer Amanda Mull laid out, it shames women for feeling bad about beauty standards that companies like Dove and others behind those ads helped create without the companies acknowledging their own part in creating those unreasonable expectations and the pain that goes along with them.24 On the other hand, it also shows the potential for what a business can achieve when it thinks differently and works to integrate social causes across its operations.

Contrariwise, what does this look like when the commitment is performative and not sustained? Well, you may remember some big news out of the Business Roundtable a few years ago. The Roundtable, an association for the executives of some of the country’s biggest companies, released a statement in 2019 with over 150 cosigners that “redefined the purpose of the corporation to promote an ‘economy that serves all Americans,’” and said “we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” not just shareholders.25

Well OK then! Problem solved, right? Not so fast. When put to the test, many of these companies went back on their commitments and suffered as a result. As research from Wharton Professor Tyler Wry found, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the stakeholder pledge signers gave 20 percent more of their profits to shareholders as compared to companies who did not sign the pledge.26 This led them to be “almost 20 percent more prone to announce layoffs or furloughs. Signers were less likely to donate to relief efforts, less likely to offer customer discounts, and less likely to shift production to pandemic-related goods.”27

We can’t know for sure why these companies did not follow through on their pledge, but, in an interview with The Atlantic writer Jerry Useem, Professor Wry suggested that it may have a fundamentally psychological reason: “If people are allowed to make a token gesture of moral behavior—or simply imagine they’ve done something good—they then feel freer to do something morally dubious, because they’ve reassured themselves that they’re on the side of the angels.”28

This book is designed to help you avoid this type of behavior. It is easy to make a quick promise and put out a statement, but it’s harder to stay committed and follow through. It requires taking a hard look at your practices and considering your business practices differently. If you can’t do that and be committed to the equitable impact you want to create, you will be seen as inauthentic and won’t be able to engage with your customers in the way they want you to. Your “authenticity” has to be real, not performative. In many cases, achieving this authentic, long-term engagement means overhauling certain practices or developing a new operating philosophy.

Defining the authentic, unique equitable impact your company can create is both very simple and incredibly complex. You find it at the intersection of three elements:

1. Your organizational passion and values

2. The root cause of the issue you are trying to solve

3. The assets you can bring to the issue

These are the components of the Equitable Impact Venn Diagram I use to help clients find their sweet spot for equitable impact (see Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 The Equitable Impact Venn Diagram

Looking at this Venn diagram, you probably could come up with an off-the-cuff statement about each of the elements and the equitable impact you could create. Your root cause issue might be a lack of good jobs in a community; your passion and values might be creating a welcoming and inclusive workplace; and your assets might be a franchise business model that creates entry-level job openings. Your equitable impact would be something around investing in the communities in which your business operates.

But the process for creating and defining what this equitable impact actually looks like is where things get complex. You can very quickly feel as if you need to do everything! Your business touches so many aspects of society, it’s hard not to get overwhelmed by the scale of the problems.

WOW. HOW DO I EVEN START?

Yes, this may seem like a lot, especially when I throw in some galaxy-brain thinking about the nature of capitalism. But, not to worry: there are simple steps you can take to help you respond to the shifting nature of your customer base, the need to be authentic, and generally the desire to do well BY doing good, and this book is all about meeting you where you are in your process and giving you a place to start. Actually, you are probably doing some of these things. So, let’s get to it.

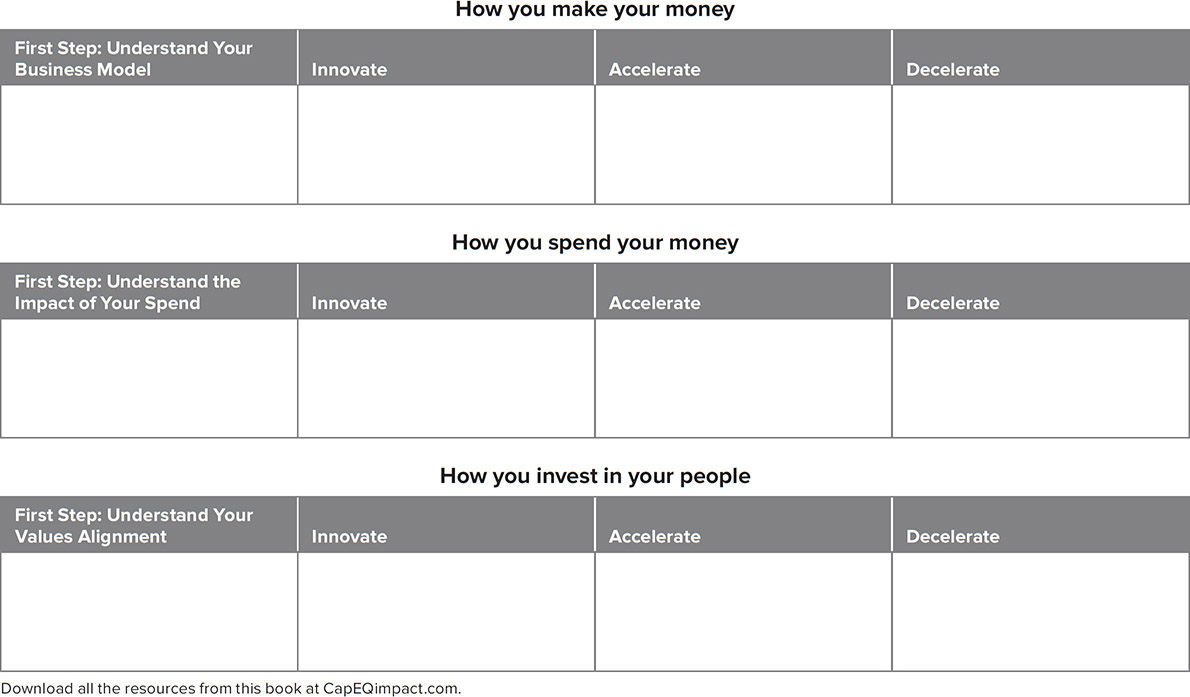

There are three areas for you to consider: (1) how you make your money; (2) how you spend your money; and (3) how you invest in your people. This can be so simple that the steps you need to take can fit on one page—in fact, if you go to Table 1.1, Good Business Definitions, you’ll see them all there!

TABLE 1.1 Good Business Definitions

This worksheet walks you through all you need to do to harness the power of equitable impact for your business. The first row focuses on how you make your money—what kind of products or services you offer, and generally how your business model helps align your profit creation with the creation of equitable impact. The second row concentrates on how you spend your money—both in terms of your inputs into your products and services, but also into ancillary things like your office supplies, benefits for employees, and even investment opportunities. The final row, “How you invest in your people,” emphasizes aligning your company values with your company practices and seeing your employees as an asset to your company, not a commodity.

The rows in Table 1.2, the Good Business Worksheet, represent the areas of focus, while the columns represent the steps to take to implement changes within each area. Each section has a “first step”—which is, not surprisingly, the first thing you need to do to make changes in your company. The other rows represent what I call the “Innovate-Accelerate-Decelerate” cycle, which is a continuous improvement process where you identify potential changes to your organization—either from outside or inside your company—and then apply them or ramp them up in your operations. You can also stop, or “decelerate,” harmful activities that are not aligned with your values or the impact you want to create.

TABLE 1.2 Good Business Worksheet

In the next three chapters, I will walk you through each section, and help you determine what makes sense for how your company can integrate elements of equitable impact into its operations. Each chapter has its own iteration of the Good Business Worksheet; the worksheet in this chapter is actually a summary of those three worksheets, which you can complete on your own or with a team. Like Doc-Scan, this section may not be the best place for you (or your boss) to start. There may be more opportunities in the next chapters, or even the final chapter about the preconditions needed to execute on some of these tasks. Or, you may just need to spend time with the business case sections to understand better how your company fits into these global trends.

As you dig deeper into the Good Business Worksheet and the next three chapters, you’ll learn that even though there are three parts to the worksheet, the process isn’t linear. You may not be able to complete the full worksheet right now, but, if that is the case, focus your energies instead on spending or values alignment. As you go through the worksheet and read each chapter, you may find a section that doesn’t resonate or is not the best place for you (or your boss) to start. If that happens, move on. There will be more opportunities in later sections or chapters—even the final chapter—about the preconditions needed to execute some of these things. You may want to concentrate on the business cases I present to understand better how your company fits into the global trends.

If you decide to implement the holy trinity of capitalism throughout your company, you will, at some point, have to complete all three elements of the worksheet. It will put you on a path to create an evolving, interlocking process that reinforces the “why” behind your Equitable Impact Venn diagram: the root cause of the problem you want to solve; the passion and values of your company; and the assets you bring through your business operations. Steps you take to complete the worksheet will help you refine how you think about equitable impact, and what you bring to tackling the problem you set out to solve. The steps build off one another and inform decisions across your company.

It’s fine to complete the worksheets on your own, but the process of completing them will be more powerful if you do it as a team. Integrating equitable impact into your company is a huge undertaking, and will be easier if you bring along critical members of your organization. Engaging key members of staff in the initial conversation will help secure their buy-in and surface the best ideas from the start. To help with this, each chapter includes a sample discussion agenda. (They are also available online at CapEQimpact.com.)

If this isn’t feasible or you are one of the few—or only—people in your company looking to harness equitable impact to help you do well BY doing good, the Good Business Worksheets can still help. They are designed as a simple way to illustrate the quick wins and opportunities for customer growth and revenue expansion. Doing them on your own can give you an important tool to help convince others to get on board with this shift in your operation. For example, you can just hand the worksheets to your boss or head of your department when you’ve completed them to clearly explain what you want to do and how you propose to do it. (For more on how to manage a change management process, check out Chapter 5 on the CapEQ™ continuum.)

You can start anywhere on the worksheet and in the chapters to come, but don’t be surprised if you end up somewhere you didn’t think you’d be. That’s the beauty of this work—you start somewhere, and you end up everywhere.