17

Apprenticeships in England

17.1. Introduction

The UK government has made apprenticeships a high-profile area of government policy. One manifestation of this is a specific target to have 3 million apprenticeship starts between 2015 and 2020. Another is the introduction of an apprenticeship levy (payable by large firms) to fund more apprenticeships. Although the target and levy are applicable across the whole of the UK, education and skills is one of the areas of government devolved across nations of the UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). The way in which the system operates, and the nomenclature, differs across the four nations and recent reform has made them increasingly different. In this short chapter, we focus on the system as it operates in England (for which we have the best data). While in most countries apprenticeships are thought of as a program of work and study for young people, as they transition from full-time education into the labor market, this is not the case for England where about half of those starting an apprenticeship are above 25 years of age. This was not always the case (and is not the case in Scotland, for example) and is a controversial aspect of the system. Another prominent feature of apprenticeships in England is that until recently, almost all were at a level deemed equivalent to lower or upper secondary education. In the last few years, higher and degree apprenticeships have emerged, although they only account for a small percentage of apprenticeship starts and it is too early to judge their impact on labor market outcomes vis-à-vis other higher education alternatives.

In this chapter, we will first explain more about what an apprenticeship is in England and how the system works (section 2). We will then discuss how numbers have evolved in recent times (section 3). Finally, we will discuss evidence on the labor market value of having an apprenticeship (section 4) before concluding.

17.2. The apprenticeship system in England

In England, the definition of an apprenticeship is as follows: “…a job that requires substantial and sustained training, leading to the achievement of an Apprenticeship standard and the development of transferable skills” (BIS 2013). There are four types of apprenticeship: Intermediate (Level 2 – equivalent to lower secondary qualifications); Advanced (Level 3 – equivalent to an upper secondary qualification); Higher (anything above this) of which a subset is Degree. Each level has different entry requirements. Vacancies for apprenticeships appear throughout the year, and the application process is similar to applying for any job1. The employer must pay the apprentice at least the National Minimum Wage for apprentices (which is below that for other workers) and any tuition fees. Much of the recent growth in apprenticeships has been for older workers, many of whom do not change employer. They are able to train for an apprenticeship because this constitutes training for a new job for which they do not have the prerequisite training (and do not have a level of education commensurate with the apprenticeship being offered).

There have been several important reforms. First, from 2012, all apprenticeships must last for at least a year (based on a 30-hour working week). Nafilyan and Speckesser (2017) evaluated this reform, finding it to affect intermediate apprenticeships in many industries. Second, at least 20% of the apprentices’ paid hours must be spent on off-the-job training (which can be regular or in blocks of time). Although notionally a requirement for many years, this has only been written into the funding rules since 2017 (meaning that employers are forced to comply). Third, the content of different apprenticeships is being changed to become more employer-focused with a different means of assessment (end point rather than continuous). This is wholesale change from apprenticeship “frameworks” to new “standards” which is still being phased in (starting in 2014). Fourth, the funding system has changed. In April 2017, an apprenticeship levy came into effect in the UK. All employers with a pay bill of more than £3 million per year pay the levy, which is set at 0.5% of the employer’s pay bill. This is paid into an apprenticeship service account, which can be drawn down by these firms to pay the training and assessment costs of any new apprentices taken on by them. About 2% of employers pay the levy, but they account for about 60% of all employees (Amin-Smith et al. 2017). Smaller employers pay 5% of the cost of training and assessment with the government paying the rest. There are many different training providers that are registered to provide the actual training. There are regulatory bodies to monitor apprenticeship standards (or frameworks) and providers. Fifth, although Higher Apprenticeships (i.e. at tertiary level) have been available for some time, degree apprenticeships are a new program. The degree and apprenticeship fund was set up in 2016 to support the development and delivery of degree apprenticeships. So far, this has helped to fund 44 projects to develop and deliver new degree apprenticeships in areas including chartered management, digital and technology solutions, engineering, construction and healthcare (Office for Students 2019).

17.3. The evolution of apprenticeship numbers

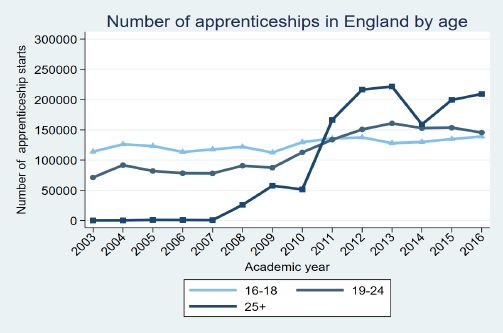

It is too early to evaluate most of the reforms described above. However, even before these reforms, much had already changed. There has been a huge increase in the number of apprenticeship starts since about 2008 (accelerating from 2010). This is shown in Figure 17.1 and is largely driven by those aged above 25. Before 2007, there were no apprenticeship starts for people in this age group. Now they account for about half. There has been significant growth among those aged between 19 and 24. The number of 16–18 year olds starting apprenticeships has been very stable between 2003 and 2016, and it is rare for individuals to go straight from school to an apprenticeship, after GCSEs (Hupkau et al. 2016). Starts among those aged 19–24 overtook 16–18 year olds in 2012 and have remained a little above them in most years since then.

Figure 17.1. Number of apprenticeship starts in England by age. Source. ILR data. Extension of analysis in Hupkau and Ventura (2017). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cerdin/learning.zip

Conlon et al. (2017) note the policy context in which the increase in apprenticeship numbers occurred. Funding for the “Train to Gain” initiative was reduced at the beginning of the 2010/11 academic year with much of it re-invested into apprenticeships2. Despite the increase in apprenticeship numbers, the overall number of people receiving publicly funded training declined (Hupkau and Ventura 2016).

The increase in the number of apprenticeship starts was concentrated within the following sectors: business, administration and law; health, public services and social care; retail and commercial enterprise; and engineering and manufacturing technologies. This is discussed in detail by Hupkau (2015), who also cites evidence that, at least within retail, health and business, apprentices were mainly recruited from the pool of existing employees rather than new entrants to firms.

Furthermore, it cannot be taken for granted that the increase in starts results in completed apprenticeships. Bursnall et al. (2017) conducted a longitudinal analysis for apprenticeships that started in 2011/12. For the cohort of all 516,880 intermediate and advanced apprentices starting in England during that year, they found one-third were withdrawn and a further 10% were not completed within 36 months. This suggests that focusing on the published numbers of apprenticeship starts and on the published achievement rates (which, to a large extent, exclude apprenticeships that are withdrawn) may not give an accurate picture of the reality of apprenticeship provision. Assuming the same pattern persisted across the 2010–2015 Parliament, the 2.4 million reported as starting an apprenticeship translates to between 1.5 and 1.7 million achievements3.

The introduction of the Levy coincided with a reduction in the overall number of starts as well as changes in their composition. For example, in 2017/18, intermediate and advanced apprenticeships declined by 38% and 16% respectively, whereas there was a dramatic increase in the number of higher-level starts, though from a very low base (Department for Education 2018). Higher apprenticeships (of which degree apprenticeships are a subset) now constitute about 10% of apprenticeship starts. Degree apprenticeships made up less than 3% of the total number of apprenticeships in 2017–18 (Office for Students 2019).

The interpretation of changing apprenticeship numbers is complicated by this change in composition. On the one hand, a recent decline in numbers has caused concern about fewer opportunities being created. On the other hand, one might argue that “higher-quality” opportunities are more prevalent in that there are increasing opportunities for people to commence higher or degree apprenticeships. It is too early to compare earnings returns between higher or degree apprenticeships and other opportunities in tertiary education. As discussed below, available evidence on intermediate and advanced apprenticeships shows that returns vary by level and by type.

17.4. What is the value of an apprenticeship?

One way to think about the “value” of an apprenticeship is to estimate the extent to which doing one leads to better employment prospects in the longer run (e.g. through earnings). This tells us something about how employers value the skills acquired as a result of the apprenticeship process.

Cavaglia et al. (2017) evaluate the earnings differentials of those starting an apprenticeship, having finished the compulsory phase of schooling (with national GCSE exams) in 2003. They follow individuals as they progress through education and into the labor market using administrative data. They evaluate the impact of starting an apprenticeship on later earnings at the age of 28 (in 2015). About 17% of this cohort had started an apprenticeship by the age of 28. The focus is primarily on the earnings differential that arises from starting an apprenticeship because the potential benefit is not only in certification but also on-the-job training, achievement of some (if not all) of the aims and potential connections made through the apprenticeship program.

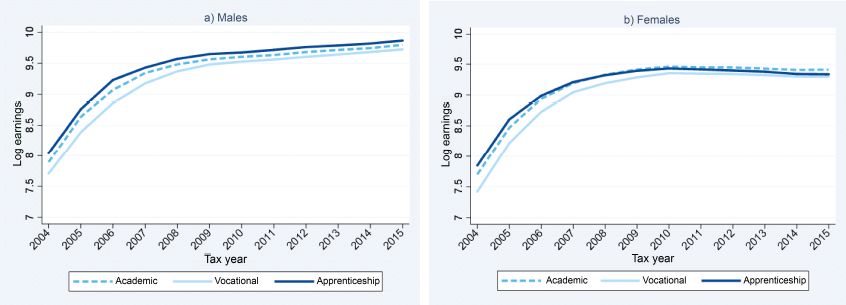

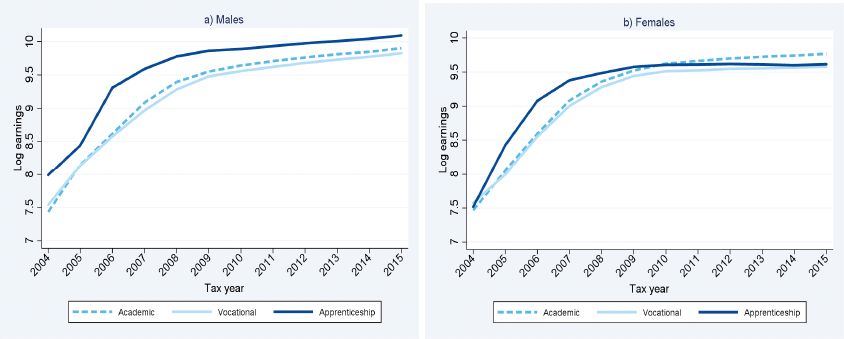

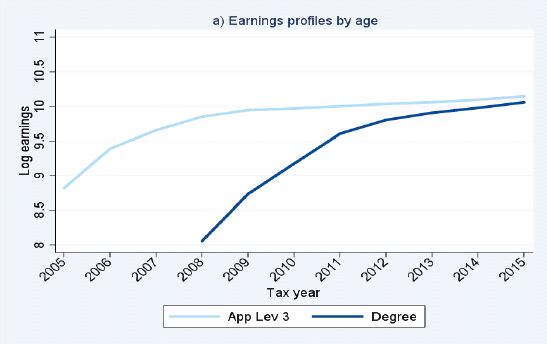

Those who start an apprenticeship are compared with those of a similar educational level. In practice, this means comparing such individuals either with those who achieved lower secondary (Level 2) educational qualifications (GCSE or vocational equivalent) or upper secondary (Level 3) educational qualifications (A-levels or vocational equivalent). For this cohort, higher apprenticeships did not exist. Figures 17.2 and 17.3 show the evolution of earnings over different tax years for this cohort of men and women (who did their GCSEs in 2003) conditional on their level and type of education. In the raw data, it is evident that the average earnings differential to starting an apprenticeship is higher for men than it is for women. Earnings trajectories are worse in general for women.

Figure 17.2. Log median earnings by year for those educated up to level 2 (maximum) (GCSE cohort of 2003). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cerdin/learning.zip

Figure 17.3. Log median earnings by year for those educated up to level 3 (maximum) (GCSE cohort of 2003). Source: Cavaglia et al. (2017). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cerdin/learning.zip

The methodological approach involves “netting out” things that make those who started an apprenticeship different from those who did not. For example, men who start an advanced apprenticeship are only half as likely to have been eligible to receive free school meals when at school (compared to the average in the cohort). There are a range of characteristics which can be controlled for: prior attainment at primary and secondary schools; demographics such as ethnicity and economic disadvantage; the secondary school attended and post-education experience in the labor market. Thus, the earnings of individuals with and without an apprenticeship are compared after taking into account all these different factors. The approach is not perfect because it does not take into account such factors as motivation, social skills and perseverance (which might affect the probability of being taken on as an apprentice, as well as earnings). So one should not interpret the earnings differential as being attributable to the apprenticeship alone.

By the age of 28, the baseline earnings for men and women are £19,709 and £13,621 respectively for those educated up to lower secondary education or Level 2. These are the average earnings of those whose highest education was GCSEs (with at least one GCSE of A*-C) at age 28 in 2015. After taking into account other factors, men who start an apprenticeship earn 23% more than those who left school with only GCSEs and roughly 16% more than those who left education with a Level 2 vocational qualification. For women, those who start an apprenticeship earn 15% more than those who left school with only GCSEs and about 4% more than those who left education with a Level 2 vocational qualification.

For those educated up to upper secondary education or Level 3, the baseline earnings for apprentices aged 28 are £22,464 and £18,500 for men and women respectively. These are the average earnings of those whose highest education was A levels in 2015, when they were aged 28. After taking into account other factors, men who start an apprenticeship earn about 37% more than those who left education with A levels (and did not progress any further). They earn about 35% more than those who left education with a Level 3 vocational qualification. Women who start an apprenticeship earn about 9% more than those who completed their education with A levels by the time they are aged 28. They earn roughly 15% more than those who left education with a Level 3 vocational qualification (without progressing any further).

Even though these earnings differentials partly capture individual characteristics, which cannot be controlled for (e.g. better “soft skills” of those accepted on to an apprenticeship program), they are suggestive of the high potential returns of an apprenticeship. However, some apprenticeships lead to better prospects than others. The gender difference is particularly striking, especially for those educated to Level 3, where the earnings differential is over three times larger for men than for women. Much of this is attributable to the sector of learning. Most men with advanced apprenticeships are classified within engineering and manufacturing technologies (53%) or construction, planning and the built environment (26%). For women, the most important sectors for advanced apprenticeships are health, public services and care (35%); retail and commercial enterprise (23%) and business, administration and law (28%). The sectors popular with men tend to have larger differentials than those popular with women. For example, the premium to starting an apprenticeship in engineering is particularly high. At the other extreme, there are apprenticeship sectors that have a negligible or lower premium than alternatives for people educated to the same level. This includes having an apprenticeship in service enterprises (such as hairdressing) for women educated to Level 2 or Level 3 and childcare at Level 3 (also affecting women)4. Thus, much like university degrees, potential “returns” of an apprenticeship vary across subject specialisms.

The above analysis considers those who started an apprenticeship, even though they did not complete one. In general, the earnings differentials are higher for completers compared to non-completers. Interestingly, men who complete an advanced apprenticeship in engineering earn more on average than men with a degree at age 28 (which is also true when controls are included)5. This is shown in Figure 17.4.

Figure 17.4. Median earnings differential for men who completed a degree versus completion of an advanced apprenticeship by year (for GCSE cohort of 2003). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cerdin/learning.zip

The implication of this analysis is that the “value” of apprenticeships (as measured by labor market earnings) differs very markedly depending on both the level and sector of apprenticeship. Furthermore, this analysis pertains to a cohort of students who undertook their apprenticeships before the big increase from 2010. The majority of these students had done their apprenticeship by the time they were 21 years of age. We need to be very careful about extrapolating these earnings differentials to recent times, where so much of the recent growth has been among those aged above 25 years – of which most are “conversions” (i.e. “converting” existing employees into apprenticeships). As discussed by Fuller and Unwin (2017), this poses two problems. First, there is a danger that these apprentices are being accredited for their existing skills without spending sufficient time training to update or upgrade their skills, or retrain in a new occupational field6. Second, the practice does not generate sufficient new employment opportunities for young people.

McIntosh and Morris (2018) investigate whether the earnings differential of an apprenticeship for older people (+24) is any different from undertaking one when younger (19–24). They find that the effect of completing an apprenticeship on earnings is two to three times larger for the 19–24 age group than for the older group. For intermediate apprentices (and female advanced apprentices), this is mainly because older works gain less from apprenticeships within the same sectors. This may be because older apprentices are more likely to be existing employees before their apprenticeship and to have shorter apprenticeships on average. For male advanced apprentices, the main reason for the lower earnings differential for older people is that they tend to undertake apprenticeships in sectors where the earnings differentials available are much smaller, such as in business administration.

With regard to other countries, it is not always the case that apprenticeships lead to an increase in wages in the medium term, over and above alternatives such as classroom-based vocational education. One of the most convincing studies on this is for Austria (by Fersterer et al. 2008) who find that a year of apprenticeship training generates an increase in pay of slightly more than 5%. There is more widespread evidence that apprenticeships ease the school to work transition for young people (e.g. as reviewed by Wolter and Ryan 2011). A recent paper by Hanushek et al. (2017) suggests that the employment advantage that young workers with apprenticeships have over those with general education in early years is reversed later in life (from about 50) – with a particularly strong pattern in the “apprenticeship countries” of Denmark, Germany and Switzerland. They conclude from this that vocational training should not substitute the provision of strong basic skills. This needs to be a core part of all education and training programs for young people.

17.5. Conclusion

Over the last 10 years, the increase in the number of apprenticeship starts has been driven mainly by those above 25 years of age (and to a lesser extent those aged between 19 and 25). Studies suggest that whether apprenticeships really “add value” depends on the sector within which they are located and the circumstances of the people who take them on. In most countries, apprenticeships are geared towards training new entrants to the workforce – and not for re-training of those already in the workforce, much less the same company. In interpreting the changing number of apprenticeship starts in England (whether up or down), as much attention needs to be given to the nature of those apprenticeships as to their volume. Furthermore, people need to be properly informed about the predictable prospects associated with doing one type of apprenticeship rather than another.

17.6. References

Amin-Smith, N., Cribb, J., and Sibieta, L. (2017). Reforms to Apprenticeship Funding in England [Online]. Available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/8863.

BIS (2013). The Future of Apprenticeships in England. Report, HM Government.

Bursnall, M., Nafilyan, V., and Speckesser, S. (2017). An analysis of the duration and achievement of apprenticeships in England. Briefing Note 4, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Cavaglia, C., McNally, S., and Ventura, G. (2017). Apprenticeships for young people in England: Is there a payoff? Discussion Paper. 10, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Conlon, G., Hedges, S., Herr, D., and Patrignani, P. (2017). The incidence of publicly funded training in England. Briefing Note 3, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Department for Education (2018). Apprenticeship and Levy Statistics 2018. Report, GOV.

Festerer, J., Pischke, J.S., and Winter-Ebmer, R. (2008). Returns to apprenticeship training in Austria: Evidence from failed firms. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110(4), 733–73.

Fuller, A. and Unwin, L. (2017) Apprenticeship quality and social mobility. In Better Apprenticeships. Fuller, A., Cavaglia, C., Ventura, G., Unwin, L., and McNally, S. (eds). Sutton Trust, London.

Hanushek, E.A., Schwerdt, G., Woessmann, L., and Zhang, L. (2017). General education, vocational education, and labor-market outcomes over the life-cycle. Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 48–87.

Hupkau, C., McNally, S., Ruiz-Valenzuela, J., and Ventura, G. (2017). Post-compulsory education in England: Choices and implications. National Institute Economic Review, (240), 42–57.

Hupkau, C. and Ventura, G. (2017). Further Education in England: Learners and Institutions. Briefing Note 1, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Hupkau. C., (2015). The Past and Future of Apprenticeship Growth in England [Online]. Available at: http://cver-blog.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/the-past-and-future-of-apprenticeship.html.

McIntosh, S. and Morris, D. (2018). Labour market outcomes of older versus younger apprentices: A comparison of earnings differentials. Discussion paper no. 15, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Nafilyan, V. and Speckesser, S. (2017). The longer the better? The impact of the 2012 apprenticeship reform in England on achievement and other outcomes. Discussion paper no. 6, Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Office for Students (2019). Degree Apprenticeships: A Viable Alternative? [Online]. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/degree-apprenticeships-a-viable-alternative/.

Wolter, S.C. and Ryan, P. (2011). “Apprenticeship.” In Handbook of Economics of Education, Hanushek, E.A., Machin, S. and Woessmann, L. (eds). Elsevier, Oxford.

Chapter written by Sandra MCNALLY.

- 1 Information on vacancies can be found on the government “find an apprenticeship” website or on the website of the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. However, not all apprenticeship vacancies get advertised through these websites.

- 2 Train to Gain was designed to deliver vocational training to employed individuals in the UK, primarily those in the 25+ age band who did not already have a lower-level (level 2) qualification. The Train to Gain scheme ended in 2011.

- 3 The extent of achievement is strongly related to measures of prior achievement and to the sector framework (as well as to the level within the sector). Overall achievement rates range from 57% in retail to 83% in accounting and 90% or more in spectator safety and the glass industry.

- 4 Note that most sectors show an earnings premium at age 23, even though they do not at age 28.

- 5 Men with an advanced apprenticeship in engineering earn about the same as men with an engineering degree at age 28 after controlling for other factors, including experience.

- 6 They also make the point that enabling adults to gain qualifications through work is very important for their mobility, but this should be done through accreditation of prior learning (APL).