29

Research on Apprenticeships

29.1. Introduction

Research on apprenticeships can help to better understand their importance in the business world and in the contemporary economic system, especially in the context of unemployment in the European Union. This research is also useful in understanding the motivations and needs of young people in order to help organizations develop better apprenticeship contracts oriented towards realistic objectives.

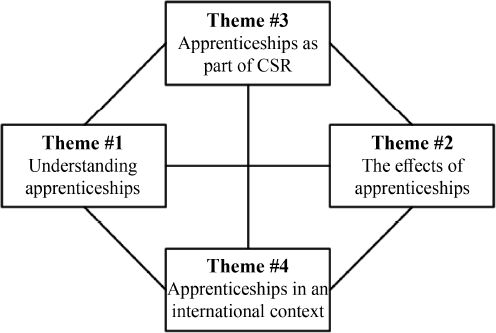

Figure 29.1. Proposals for a research program on apprenticeships

This chapter, organized into four different themes, provides a comprehensive picture of apprenticeships by presenting their various components and outlining a profile of the stakeholders. The objective is to better understand how the different actors contribute to the apprenticeship process. This chapter also proposes a research program focused on four main themes, summarized in Figure 29.1.

These themes are presented successively before research avenues are sketched out.

29.2. First theme: understanding apprenticeships

Apprenticeships inform how individuals react when they experience changes in perceptions, behavior, values or attitudes in their workplace. They also contribute to the development of self-esteem, competence and effectiveness (Gouillart and Kelly 1995). It is therefore important to conceptualize apprenticeships and analyze the relationships between the stakeholders in this process.

29.2.1. Defining apprenticeships

The objective here is not to define an apprenticeship in a particular legal or national context, but rather in a general way. Apprenticeships can be defined as a type of job which is at the same time on-the-job training (Gospel 1998). This contractual arrangement for training brings with it certain rights and duties for the two main stakeholders in the process: (a) the employer and (b) the apprentice (Gospel 1998; Malcomson et al. 2003). The training organization is also a key stakeholder in organizing apprenticeships and issuing a diploma that validates them. Usually, the employer is responsible for providing apprentices with the skills of the trade (Gospel 1998; Gospel and Fuller 1998). The duration of the apprenticeship is usually a minimum of two years, at the end of which the apprentice is granted a recognized professional diploma (Ryan 2000). During the apprenticeship period, even if apprentices acquire the required skills, they do not receive a salary equivalent to that of skilled employees but continue to work in exchange for the salary agreed upon prior to the contract (Malcomson et al. 2003). The apprentice’s salary increases gradually as the apprenticeship progresses (Gospel 1998). Traditional apprenticeships differ from full-time studies in three main ways: apprentices spend more time at work than in class, they receive wages during their studies and the employer is responsible for their training (Ryan 2000).

One way to measure the success of an apprenticeship is the ease with which the apprentice makes the transition from school to work. Another is the sum of the knowledge acquired by the apprentice during his or her apprenticeship. Apprenticeship programs must be evaluated to ensure their effectiveness in these two areas. Instructors must also be able to assess apprentices’ engagement in their training and measure their potential. However, assessing competencies is not an easy task: several dimensions need to be examined, and the competencies involved are very complex and difficult to grasp.

29.2.2. Stakeholders in the apprenticeship process: the threefold relationship in its context

The relationships between the stakeholders in the process are characterized by the following aspects:

- – an institutional aspect: the contractual agreement between several parties. For example, professions are represented by industrial sectors and companies and training is provided by different state institutions or other private training organizations;

- – an organizational aspect: the contractual agreement between two institutions – the training organization and the company. For an apprenticeship to be an educational and collaborative project, it requires the commitment of the partners involved;

- – an operational aspect: the contractual agreement between the three stakeholders: young apprentices, tutors and instructors. This level concerns the organization of training and education. Thanks to this dimension, young people can be involved in the construction of their professional project (Schneider 1999).

29.3. Second theme: the effects of apprenticeships

An apprenticeship includes two main and inseparable functions: the transmission of professional practices and the socialization of young people (Casey 1986; Booth and Satchell 1994; Gospel 1998). Apprenticeship programs have both short- and long-term effects on apprentices, training organizations, and businesses that train and hire apprentices.

29.3.1. The contribution of apprenticeships to the career development of young individuals

For apprentices, the knowledge and content of their training makes sense during the apprenticeship period and also gives meaning to their future projects. As industrial sectors become increasingly isomorphic through a series of innovations and mimicry, jobs end up looking more and more alike. The completion of an apprenticeship in one type of organization therefore allows the apprentice to do similar work in another organization. Casey (1986) even estimates that an apprentice who has successfully completed his or her training has an increased chance of finding a job, even in a completely different sector. In order to measure the contribution of apprenticeships to career development, it is necessary to compare the careers of people who have gone through apprenticeships with those of others.

29.3.2. The effect of apprenticeship management on the development of training organizations

An apprenticeship plays a very important strategic role for training organizations: it improves their image and attractiveness to potential students and allows the school to strengthen its legitimacy with organizations, as well as to build closer links between the school and organizations.

29.3.3. Apprenticeships within a broader talent management program within organizations

An apprenticeship is a type of formal relationship that can be used to train and socialize new managers. An advantage for the organization is that apprenticeships reduce the turnover rate by linking the apprentice and his or her employer for a few years (Ryan 2001). Another advantage for the organization is that it can decide, at the end of the apprenticeship, to hire the apprentice if it wishes (Casey 1986).

29.4. Third theme: apprenticeships as part of CSR

Apprenticeships can be used as a form of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) activity to signal to various stakeholders that the organization is behaving responsibly and for the good of society in general. Of particular interest are the social benefits that can be achieved when organizations go beyond the simple pursuit of monetary gains and engage in apprenticeships for the social good. From a CSR perspective, apprenticeships can be understood as mechanisms to meet social expectations and promote national, governmental or local policies. Apprenticeships are often seen as a factor that leads to a reduction in unemployment in countries such as Germany (Casey 1986). In Europe, countries with existing apprenticeship systems have higher employment rates among the young population than countries where this process has not been implemented (Ryan 2001). Beyond the general objective of reducing youth unemployment and facilitating a smooth transition to productive work, apprenticeships also have specific organizational objectives, such as maintaining good relations with various actors – trade unions, governments, training organizations, etc. (Booth and Satchell 1994).

29.4.1. Intergenerational transmission of knowledge through apprenticeships

Beyond the pursuit of profit, organizations have a role to play in the transmission of knowledge between generations. An apprenticeship makes it possible to exchange information, transfer knowledge and ensure the continuance of good practices between two generations. Apprentices, drawing on their teaching as well as their personal experience, can play an important role in the transmission of knowledge within the company (Fuller and Unwin 2004; Van de Portal 2009).

29.4.2. The company’s formative roles

The notion of responsibility has undergone significant changes in recent times. Previously, a company’s training policies emphasized the virtues of support, common commitment and the duty to transmit knowledge. All these ideas are currently being challenged within the framework of the learning organization. In recent times, companies have focused on integrating the apprentice into the company (Sauvage 2000). This strategy aims to jointly develop young people’s skills in partnership with a training center. Training responsibilities are exercised through external training partnerships (associations, local authorities, training center instructors) and internal organizational programs (employees involved in the training of young apprentices). The apprenticeship system has democratized access to business school.

29.5. Fourth theme: apprenticeships in an international context

For manual workers, apprenticeships have been the main method of training and acquiring intermediate skills (Gospel 1998) since at least the Middle Ages (Malcomson et al. 2003). In Germany and England, apprenticeships were linked to guilds. Originally, an apprenticeship was reserved for craftspeople. After industrialization, this practice was extended to engineering, shipbuilding, plumbing, etc. (Booth and Satchell 1994). Much more recently, particularly in France, business schools and universities have opened up apprenticeships to management training. Apprenticeships in the international context could focus in detail on the functioning of several models such as the German, British and French models. The way in which apprenticeship programs could also integrate international mobility is also a research area to be developed.

29.5.1. The German model

Germany has a successful apprenticeships model. This success is due to the commitment of various actors, such as trade unions, the State, employer representatives and schools, who come together and create social partnerships to agree on the regulation of the system through legal bodies made up of interested actors (Ryan 2000). The involvement of educators in the administrative part of an apprenticeship also contributes to success because it ensures the high quality of these programs (Ryan 2001). The German model is difficult to imitate because of historical, cultural and institutional barriers in other countries (Ryan 2000). For example, while Germany promotes professional skills through apprenticeship practice, in France, general education occupies a privileged place (Kieser 1994). However, this does not mean that institutional factors make progress impossible: while France and Ireland had put in place institutional powers unsuited to implementing successful apprenticeship programs, they have managed to reform their structures (Ryan 2000).

29.5.2. The British model

In England, after a period of decline, apprenticeships were reintroduced by combining traditional and new elements under the name of “The Modern Apprenticeship” (Gospel 1998). This modern apprenticeship has the following characteristics: a written agreement between the apprentice and the employer, an agreed duration of the apprenticeship, off-the-job training delivered by private schools or suppliers, the option of changing professions, consideration of more than 70 occupations, improved access for female candidates and minorities, greater employer involvement and government support in the form of subsidies (Gospel 1998; Gospel and Fuller 1998). The renewal of apprenticeship in Britain was the result of an effort to copy the successful German model (Gospel 1998).

A recent change in government policy has brought a new focus on apprenticeships as tools to increase productivity and social mobility and improve people’s wages and employment prospects. CIPD (the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development) (2018) highlights a net gain for the employer when the apprentice is in training, and even more positive effects when the apprentice is hired. The gains of an apprenticeship, for both employer and apprentice, would merit further study for the different apprenticeship models.

29.5.3. The French model

For a long time, the perception of apprenticeships in France was negative, that of a system set up for the benefit of young people who were not able to achieve good academic results. The system existed mainly in small craft enterprises, and the perception of on-the-job training was not very favorable. The 1987 Séguin Act introduced the apprenticeship system at all levels from higher education to master’s level, including prestigious business and engineering schools. Today, learning is increasingly appreciated and developed (Dietrich and Weppe 2010). In France, there currently are about 400,000 apprentices, compared to only 160,000 in the 1970s. This increase is particularly pronounced in the highest ranks of higher education, where 20% of apprentices are found. Since 2003, the number of apprentices has increased steadily: a 30% increase in the number of bachelor’s degrees and a 60% increase in the number of master’s degrees (Alves et al. 2010). The apprenticeship system in France was set up in the 1920s in accordance with the tradition of the merchant guilds. In France, apprenticeships make it possible to link training in university courses (Bonnal et al. 2002) with on-the-job training. Throughout 2010–2011, according to statistics from the Ministry of National Education, there were 426,280 apprentices at all levels, from level V (vocational training certificate obtained from a secondary school or a final diploma such as CAP or BEP) to level I (master’s degree or Grande École diploma) (Repères et Références Statistiques, 2012, pp. 152–153). According to figures from the Ministry of National Education, 11.7% of students in higher education (not counting the vocational training certificate obtained in BTS after two years of study) have gone through an apprenticeship. These figures are currently stable. In 2019, a major reform of apprenticeship in France was introduced to make this route more attractive. This reform consists in particular of transforming apprenticeship training centers (CFAs) into profit centers, with the possibility for companies to create their own CFAs. Apprenticeship is also open to a wider audience, particularly in the context of continuing education. The reform recommends, without making it mandatory, the creation of a certification for apprenticeship teachers. Future research will be able to examine the extent to which this reform has achieved its objectives, including facilitating better integration into the labor market through an apprenticeship. The internationalization of the system is also encouraged, which also opens up a promising field of research.

29.5.4. International mobility in apprenticeships

Research on different apprenticeship models by country would help to understand:

- – how each model has developed;

- – what the success factors are for each model;

- – how they can inspire other models.

Beyond the models themselves, research could address the extent to which the international mobility of apprentices would enable them to develop appropriate skills. What types of international mobility for what types of apprenticeships? The articulation of apprenticeships and international mobility remains a promising avenue for research.

29.6. Conclusion

First, we discussed the need to question what an apprenticeship is and what the issues at stake and the roles of each of the parties involved in the contract are. We also looked at the issue of apprentice assessment measures. In the future, research should be conducted to identify the conditions necessary for the successful development of apprentices’ skills, in particular, how to catalyze apprenticeships and the ability of educators to transmit knowledge. In analyzing apprenticeships in these three areas, it is necessary to focus on students’ perception of an apprenticeship as a process for developing their management skills, and to study the relationships between the various stakeholders and the obligations associated with them. Research on these relationships can also help to manage the benefits and challenges faced by students in the context of both ongoing and workplace learning.

Under the second theme, we discussed the short- and long-term influences of apprenticeships at the individual (apprentice), organizational (employer) and institutional levels, including higher education institutions. It is not easy for apprentices to immediately apply the experience they gained during apprenticeships. The firm should therefore be prepared to distinguish between simple productive hours and hours devoted to apprenticeships, which can be seen more as a form of investment (Imbs 1999).

The third theme proposed exploring apprenticeships at the societal level. Those involved agree that an apprenticeship enables young people who are on the margins of the traditional education system and, sometimes, even on the margins of society, to find their place by developing an identity and a professional project.

The fourth theme encouraged to draw up a comparative table of the history and organization of apprenticeships, particularly in Europe. By highlighting the role of tradition, outlining developments and comparing apprenticeships in different countries, research can help to understand how an apprenticeship is defined, supported, developed, modified, rationalized, communicated and practiced in different international contexts. In the future, studies on the development of apprenticeships in other countries will provide a better understanding of the differences between the perception and management of apprenticeship programs. Such comparisons may also highlight factors that contribute to the success or failure of apprenticeships. Overall, such studies can help to create and develop more effective programs. In conclusion, it can be noted that a well-designed apprenticeship program has the following advantages:

- – policy makers will benefit from a better understanding of the contribution of apprenticeships to the acquisition of skills by apprentices;

- – apprentices, as future managers, will be better served if they have the opportunity to develop appropriate skills for their future;

- – trainers (teachers, professors) will be able to better support apprentices.

The four proposed research themes are aspects of apprenticeships that can be addressed independently or in relation to each other. Rigorous research will help us to understand how to improve the apprenticeship system so that students and other stakeholders, training institutions and companies can benefit further.

29.7. References

Alves, S., Gosse, B., and Sprimont, P-A. (2010). Les apprentis de l’enseignement supérieur : de la satisfaction à l’engagement ? Management & Avenir, 3(33), 35–51.

Bonnal, L., Mendes, S., and Sofer, C. (2002). School-to-work transition: Apprenticeship versus vocational school in France. International Journal of Manpower, 23(5), 426–442.

Booth, A. and Satchell, S. (1994). Apprenticeships and job tenure. Oxford Economic Papers, 46(4), 676–695.

Casey, B. (1986). The dual apprenticeship system and the recruitment and retention of young persons in West Germany. British Journal of Industrial relations, 24(1), 63–81.

CIPD (2018). Apprenticeships: An introduction. Understand what apprenticeships are, their role in workforce development, and the current UK policy context. Information sheet, CIPD, London.

Dietrich, A. and Weppe, X. (2010). Les frontières entre théorie et pratique dans les dispositifs d’enseignement en apprentissage. Management & Avenir, 10(40), 35–53.

Fuller, A. and Unwin, L. (2004). Challenging the novice-expert dichotomy. International Journal of Training and Development, 8(1), 32–42.

Gospel, H. (1998). The revival of apprenticeship training in Britain? British Journal of Industrial Relations, 36(3), 435–457.

Gospel, H. and Fuller, A. (1998). The modern apprenticeship: New wine in old bottles? Human Resource Management Journal, 8(1), 5–22.

Gouillart, F.J. and Kelly, J.N. (1995). Transforming the Organization. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Imbs, P. (1999). L’apprentissage dans l’enseignement supérieur : un champ d’investigation pour la recherche en ressources humaines. IAS, August.

Kieser, A. (1994). Why organization theory needs historical analyses – And how this should be performed. Organization Science, 5(4), 608–620.

Malcomson, J., Maw, J., and McCormick, B. (2003). General training by firms, apprentice contracts, and public policy. European Economic Review, 47, 197–227.

Ministère de l’Éducation nationale (2012). Repères et références statistiques sur les enseignements, la formation et la recherche AERS (2012). Lecture notes, RERS, Blois, 152–165.

Van de Portal, M. (2008). L’accueil des apprentis en formation supérieure. Revue française de gestion, 10(190), 31–42.

Ryan, P. (2000). The institutional requirements of apprenticeship: Evidence from smaller EU countries. International Journal of Training and Development, 4(1), 42–65.

Ryan, P. (2001). The school-to-work transition: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Economic Literature, 9(1), 34–92.

Schneider, J. (1999). Réussir la formation en alternance. INSEP, May, 216.

Chapter written by Kushal SHARMA and Jean-Luc CERDIN.