CHAPTER 5

THE STATE’S OBLIGATIONS

Imagine a large, economically powerful country. It’s large in land area and population, with a booming manufacturing sector exporting to the world. Yet despite its huge strides, poverty is still a real issue. Smallholder farmers are seeing their livelihoods fail, their farms affected by desertification, soil degradation, and unstable global prices. Factory workers are working in unsafe conditions for little pay. Cities are expanding, but are also seeing expanding slums, with more urban migrants living in insecure and unsafe housing.

Despite these challenges, the government has adopted a bold vision of how to manage the economy. It institutes price controls, both to sustain important industries and to ensure that necessary goods are not too expensive for ordinary consumers. Generous support is offered to farmers, the young, the unemployed, and the elderly. The government puts constraints on the banking system to prevent it from destabilizing the economy. It intervenes in the labor markets, putting government weight behind workers’ attempts to ask for better wages and working conditions. It tries to bring together important industries to prevent cutthroat competition leading to overproduction and waste. It drives mass support for private home ownership, bringing needed wealth to people who had never owned a home. It increases taxes on the wealthy to redistribute the nation’s income toward its poor.

More important, the government embarks on an ambitious program of rural investment. Labor in rural communities is put to work expanding government infrastructure, building roads, trains, dams, airports, hospitals, and schools across the country.

As similar as this sounds, this is not China in the twenty-first century. It is the US in the 1930s during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal recovery from the Great Depression. The program featured many elements that would be unthinkable in today’s America:

• Controls on the financial sector to prevent instability, such as deposit insurance implemented to protect ordinary people from bank failures. Regulation also separated retail banking from investment banking, preventing banks from gambling with their clients’ deposits.

• The National Labor Relations Board, which helped mediate labor disputes, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, which instituted minimum wages and maximum hours.

• The Social Security Act, which provided retirement income for elderly Americans.

• The National Recovery Administration, which managed private industries to increase industrial output.

• The Agricultural Adjustment Act, which provided farmers with economic relief and financial support to ensure that small farmers could remain a going concern.

• The Works Progress Administration, which employed millions of people around the US to work on important projects. Workers built city halls, bridges, tunnels, dams, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings. There was even money allotted for artists, writers, historians, and playwrights.

With his New Deal, President Roosevelt has been credited with not just saving the US from economic catastrophe but also building a durable political coalition that sustained these programs for decades afterward. This was a broad-based platform of activist government, engaging in protecting the economic rights of both urban and rural areas. And the population largely supported his actions, with Roosevelt winning landslide electoral victories and record-high approval ratings (though some of this was inflated by the outbreak of World War II).

Despite the success of the New Deal, its lessons were lost in the 1970s. Faced with economic stagnation and the energy crisis, conservative politicians promised that economic growth and regeneration could only occur when the free market was unleashed and government was shrunk, beginning the period of so-called Reaganomics. Slowly the government institutions that had helped support, manage, and regulate the economy were rolled back, weakened, or removed entirely.1

Much of this move was driven by ideology. Conservative movements in the West, such as Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party and Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party, embraced the free-market ideas of “neoliberalism,” which simplified all of society down to market principles. Questions of value—rights, morality, obligations, and so on—“must be submitted to a purely economic analysis,” as Stephen Metcalf explains. He continues that “economics ceases to be a technique . . . for achieving desirable social ends, such as growth or stable money. The only social end is the maintenance of the market itself.”2

As neoliberalism took over, first in academia and then in politics, the West began to push other societies to more closely follow in its footsteps: cutting social spending, cutting regulations, and placing wealth creation at the top of the agenda. International institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank pushed these policies on numerous developing countries, often when those countries were in dire straits; the IMF consistently attached these neoliberal policies to its debt relief packages for countries in crisis.

But the success of a more state-driven economic agenda in the middle of the twentieth century reminds us that there is nothing inherently Asian, African, or anti-Western about the strong state. State strength in the US, in China, and elsewhere around the world has led to broad-based economic development. In some cases, such as Vietnam, Rwanda, and Cambodia, a strong state has been able to improve economic outcomes in the aftermath of devastating conflict.

Rwanda in particular is a compelling example. Commentators have marveled at how well the country has recovered from the genocide of one million people. President Kagame has accepted donor and international aid, but rather than following external strictures, he has pursued his own agenda on how best to “have a country that really works, everybody speaks English, the Internet is super fast, the airport is free of corruption, [and] lure to Rwanda all the companies and economic interests that are working in this entire region.”3 The country now has the longest life expectancy in the region, improving from 48.3 years in 2000 to 66.1 in 2015, and its economic growth, at 8 percent, is among the best in Africa. The Financial Times—not normally a publication that celebrates more activist governments—described the country as “Africa’s most orderly and disciplined society” where “flowerbeds are immaculate, villagers wear shoes (by decree) and local officials strain to make targets, whether raising cassava yields or reducing maternal deaths.”4

It is time to use the lessons of the New Deal and other instances of state-driven economic development after World War II in the developing world to tackle the next challenge: building an economy that will survive a hot, crowded, and constrained twenty-first century. One where the state is judged by the establishment of peace, rising education standards, law and order for the needs of the time, security, and health.

Chapters 1 through 4 discussed why arguments for non-state-led governance to address sustainable development need to be challenged, as only the state has the ability to intervene and coordinate throughout an entire economy.

This chapter will present the book’s alternate model for meeting our sustainability challenges: the sustainable state. This is a government which ensures that all people receive the basic “rights of life” through equal and fair access to resources. It needs to be competent, committed to the task of nation building through self-sufficiency (not dependent on aid), and strong but trusted by the people by virtue of results—not by ways that appease posturing political leaders from the West or the international media. The government has obligations toward its whole population; its legitimacy and accountability derive from its ability to universally provide these basic rights without overextending its use of resources in an unsustainable manner. In a resource-constrained era, this means directly working to provide these rights among the poor and middle classes, while constraining the consumption of the upper classes to ensure that resources are not overexploited, or mismanaged by elites.

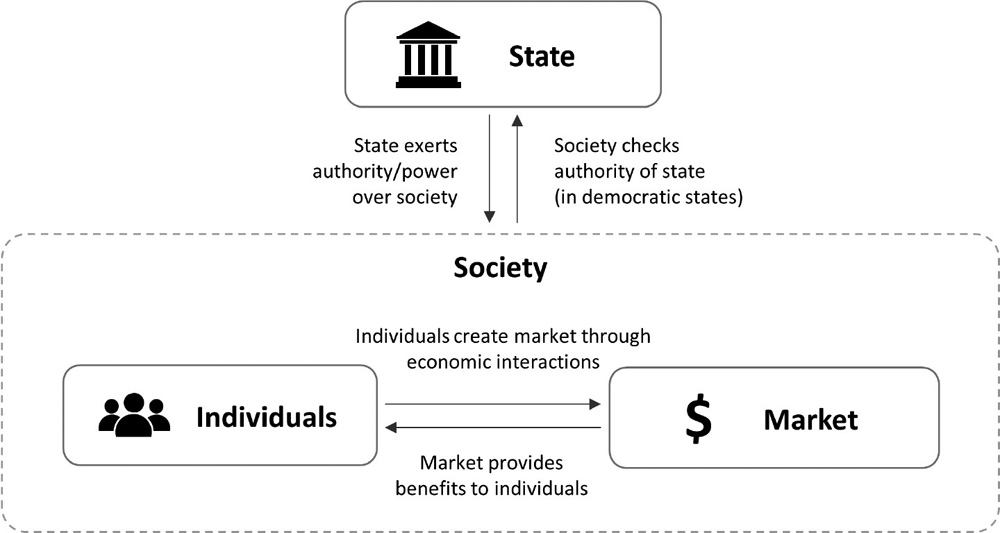

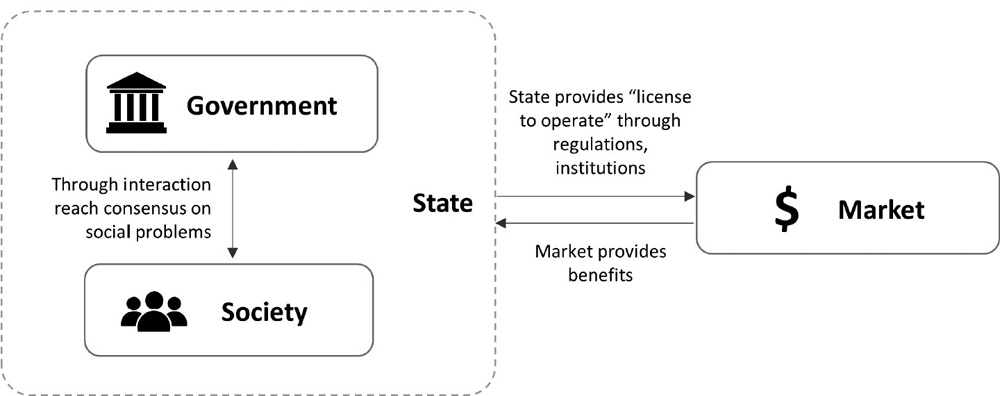

The sustainable state must have the ability and the will to consistently intervene in and ultimately manage the economy. This means that the state must be strong—that is, it must be able to both define and carry out social, political, and economic objectives. A weak state—one that is unable or unwilling to act or that delegates its responsibility to third parties—will be of little use in implementing sustainable development. Figures 5.1 and 5.2 compare the traditional understanding of the state with this book’s understanding.

Figure 5.1 The traditional understanding of the state.

Figure 5.2 This book’s understanding of the state.

What are the basic rights of life? They are the necessary elements of a basic standard of living; by virtue of being human, each person deserves to have these rights fulfilled.

People deserve the very basic necessities to survive: an adequate amount of nutritious food for oneself and one’s family; clean water; and a shelter that is sturdy, secure, and safe from the elements. They deserve safety from violence, whether from natural disasters or from human conflict.

People deserve the ability to live long and healthy lives, which in practice means living with adequate sanitation, access to disease prevention materials, and high-quality and affordable treatment. They also deserve access to a good level of education for their children, not to build software or to become wealthy entrepreneurs but instead to provide valuable assets and skills to local economies.

Finally, there is the ability to work. Everyone deserves the opportunity to work so that one can provide for oneself and one’s family, thereby making a societal contribution and escaping the indignity of being a burden. This does not have to be a formal career: working the land on a smallholder farm can be more compelling, even though it may “pay” far less, than working in harsh conditions in a factory. But whatever calling one follows, it needs to be able to provide enough for a person to live on and support dependents.

These rights define “sustainable development” for the world’s majority. This is why artificial intelligence, robotics, and automation are so threatening to sustainable development in the developing world and must be challenged. These technologies deny ordinary people access to careers and occupations that can provide for a proper household. Workers lucky enough to keep their jobs will be forced to work harder and for less pay to compete with automated factories. Further, small businesses and farms will no longer be able to compete with mechanized and automated factories and farms, pushing more and more market power (and thus political power) to big, and often foreign, companies. All these repercussions have been seen in Western countries, such as the US, which at least had the benefit of a few decades of nonroboticized manufacturing that grew the middle class; developing countries have not had the same luxury. So, apart from taxing robots (as suggested by Bill Gates), governments should not rule out banning robots in certain parts of the economy.

The basic rights, the concept of “rights” in general, and how they connect to “prosperity” will be explored in greater detail in chapter 8. But I want to highlight that creating the conditions through which these basic rights are met for the majority requires fair and equal access to resources. When this access is restricted, we see income and wealth disparity, entrenched poverty, and social unrest.

![]()

The book’s introduction brought up “the India question,” or the idea that it is impossible to achieve both sustainability and development at the same time through the free market. The way out of this dilemma can only come from governing the economy through active state management to deliver on its obligations to what will soon be the largest population on the planet. Such a state will need to treat resource management as the center of economic planning, rather than treating it as an afterthought to growth, consumption, and production.

This is what differentiates the sustainable state from the developmental state discussed in chapter 1: whereas the developmental state uses state resource management to drive high economic growth, the sustainable state will use it to create a more sustainable, universal economy—which may come at the expense of meeting perpetual high growth rates, but guarantees stability and human rights as defined via the lens of sustainable development, and vastly reduces our currently disastrous impacts on the environment.

The current sustainability crisis means that the state needs to take a more active role in managing resources. As common resource stocks become more strained, the government must step in to assure that populations have equal access to these stocks.

The sustainable state has three main objectives:

1. It must protect public and common goods to ensure that all people have equal and fair access to them. This would help ensure that all people have access to and receive what I have called the basic rights of life.

2. It must define a path toward a moderate prosperity (as opposed to the no-holds-barred understanding of prosperity we have today) that is better suited to the resource constraints of the twenty-first century and the national need for built-in self-sufficiency.

3. It must structure the economy to internalize market externalities, allowing for a more honest understanding of productivity, economic benefit, and economic cost. It must also invest in “infrastructure”: the supporting capital and services that act as the foundation on which resources are equitably shared and smaller, cleaner, and more sustainable businesses and economies can be built.

Some of the implications of these terms will be described in chapter 8, but in short: moderate prosperity refers to a standard of living that goes beyond just fulfilling basic needs, enabling people to live lives of relative comfort and ease. It is not built on the dream that everyone can get rich. It is an understanding of prosperity that looks at how the collective is living rather at individual levels of wealth and comfort. That is what a true democracy would aim to do: work to support the whole population in its collective growth, rather than merely opening the path for some to succeed at the expense of everyone else. One of the jobs of the sustainable state will be to define what standard of living is sustainable. But one thing should be clear: “relative comfort” is not the same thing as the “middle-class lifestyle” as understood by the West.

Table 5.1 Examples of state obligations and some associated trade-offs arising from tough policy action.

State Obligations (Examples) |

Tough Policy Action and Resulting Trade-Offs (Examples) |

Affordable housing for all |

Implement controls on the housing market Would give up using state land for private profit maximization (with resulting tax revenues) Thereby ensuring affordable housing for whole population |

Rural economic development to reduce urban drift |

Direct investment to infrastructure in rural areas Would create a shortage of cheap labor from rural areas to benefit urban areas Thereby building more vibrant and stable rural economies |

Resource management |

Take a long-term view of resource management Would give up short-term economic growth that could be gained from resource overexploitation Thereby avoiding the spread of irreversible damage and starting to resolve reversible changes, thus supporting intergenerational equity |

Protection of forests, wilderness, and nature parks |

Create “no-go” areas that cannot be used for economic development Would give up short-term economic growth benefits from such developments Thereby rejecting vested interests in the timber industry, industrial agriculture, and tourism |

Prevention of obesity among young people |

Ban fast food in schools and institute compulsory physical education Would restrict economic activity by private enterprise in schools Thereby contributing to better student health |

What follows is a brief discussion of how the sustainable state might achieve these three objectives, using the tools of state management of the economy. Table 5.1 presents some key obligations a sustainable state might try to achieve as well as the trade-offs that would arise from such tough policy actions.