The Strategy Paradox

The importance of risk management, the exploitation of available information, and providing employees with clear guidance on the relationship between their role and overall aims of an organization means most firms establish a clearly defined, formalized strategy to guide their operations. The purpose of the strategy is to define the benefit that provides the basis for the competitive advantage through which to achieve specified performance. Strategy implementation is achieved through utilization of an appropriate marketing and internal value-added activities (Chaston 2013).

The use of strategy in the real world is evidenced by the fact that, in many major consumer goods companies, annual plans are guided by the overall strategy that is deemed most capable of supporting a positioning that will ensure achievement of forecasted performance (Mahdi et al. 2015). Although there is no reason to doubt the benefits that a strategy may confer, some researchers, especially those examining the behavior of entrepreneurial organizations, have identified cases where an organization is performing well, but there is no evidence that activities are being guided by a clearly defined strategy. Furthermore, materials concerning the activities of entrepreneurs such as Larry Page and Sergey Brin during the development of the technology that provided the basis for launching Google, or Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim’s creation of the online video streaming proposition YouTube, evidence the primary focus of such individuals was about validating the technical feasibility of their idea, without any attempt to define a marketing strategy to guide their development activities (Chaston 2016).

Mintzberg’s (1990) explanation for the lack of strategy during the development of an entrepreneurial proposition was that where a marketing strategy exists, this has evolved gradually over time, as individuals acquire a deeper understanding of the factors influencing success. Mintzberg’s (1999) typology for this type of strategic behavior is this is reflective of a “Learning School” approach to organizational management. In his view, the conventional linear sequential planning approach, which he described as the “Design School,” involves the specification of a deliberate, detailed strategy, which, in his opinion, no longer remains feasible in today’s increasingly uncertain world.

In commenting on the relationship between the existence of clearly defined strategy and firm performance, Dess, Lumpkin, and Covin (1997) posited this depended on factors such as a firm’s competitive environment, organizational structure, position of the product of the product life cycle (PLC) curve, and speed or magnitude of technological change. Support for this perspective is provided by Covin and Slevin (1990), who empirically determined that in a hostile, rapidly changing, or heterogeneous market environment, higher financial performance was achieved by firms that had avoided being locked into utilizing a clearly articulated strategy to the define nature of the marketing process.

Playbook Guideline 52: Technological entrepreneurial successes are rarely the outcome of a carefully crafted long-term organizational strategy

Strategy-As-Practice

The traditional perspective on strategic planning is this is a formal, process-based activity involving an examination of the external environment and internal capabilities. An alternative model is that based on organizations developing and reining their strategies incrementally in the light of new information and opportunities. Research to generate understanding of this later model has involved redirecting the research away from the strategy process to focus on strategy-as-practice (S-as-P). This latter orientation emphasis is concerned with the tacit knowledge of how things work as opposed to the explicit knowledge of formal strategic planning models (Whittington 2003).

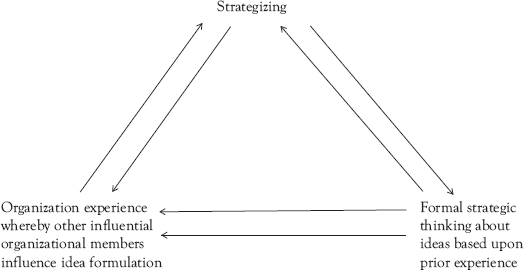

Jarrat and Stiles (2010) opined that in the context of S-as-P there is an interaction between the strategist, the organization’s collective structures, and the activity of strategizing (Figure 7.1). The strategist, who often is the founder in a small firm and a member of the senior management team in larger organizations, draws upon their own experience and frames of reference to evolve an appropriate strategic philosophy. Their position in the organization and allocated responsibility for strategy determination means their strategizing is likely to be highly influential within their organization. The degree to which their ideas are accepted will depend on the nature and outcome of interaction with others within the organization, whose own views are reflective of prior experience and involvement in learning.

Figure 7.1 The strategising process

Source: Modified from Jarret and Stiles 2010.

Jarrat and Stiles concluded that the views and decisions of the strategist are influenced by their perspective on matters such as environmental stability, intensity of competition, and their organization’s internal capabilities. Where the strategist is confident that the future will be similar to the past, the tendency is to rely upon structured, analytical models to validate the selected future with the outcome often being little alteration in the organization’s business plans. In those cases where the future is perceived as dynamic and complex, such as that to be expected for an organization engaged in technological entrepreneurship, the strategizing process will usually involve the strategist in reflective thinking about a wide range of possible scenarios. These are then widely discussed within the organization before any final decision is reached. The researchers further concluded that where the future is perceived as dynamic and complex, the strategist will accept that traditional methodologies and planning tools are unable to capture and permit analysis of the current and emerging environment.

A key factor influencing strategy is market understanding. Where an entrepreneur is engaged in idea generation at the early stages of a radical innovation, there is likely to be little or no information available on the nature of the market into which the new proposition is to be launched. Under these circumstances, the entrepreneur is forced to rely upon intuition to guide the development process, based on their own internal mental map of how their idea can be converted into a viable commercial proposition (Chaston and Sadler-Smith 2012). Once the new proposition has evolved into a tangible entity and introduced to the market, this activity will generate new information that begins to enhance the entrepreneur’s understanding of issues such as customer need, potential revenue, and reaction of competition. Over time, the depth and degree of understanding will continue to increase, and this can be expected to be accompanied by the emergence of a more well-defined strategy for guiding the marketing process.

Playbook Guideline 53: In the case where minimal market information is available, technological entrepreneurs will tend to rely upon intuition

Emergent Strategy

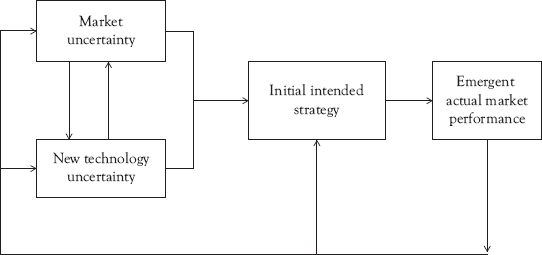

Covin, Green, and Slevin (2006) opined that entrepreneurial strategies are more likely to be emergent (i.e., realized patterns of actions not explicitly intended) than deliberate. As illustrated in Figure 7.2, identified uncertainty in relation to markets and new technology is a crucial constituent that influences the strategy-making process (Elbanna and Child 2007). Chari et al. (2014) identified two important dimensions of uncertainty, namely market dynamism reflected in rate of market change and technological instability over time.

Emergent strategies will evolve over time, reflecting the influence of organizational learning that occurs as new knowledge is acquired about markets and ongoing development of new technology. Feedback from the market and internally in relation to organizational processes will cause managers to reconsider and fine-tune the scope of their marketing strategies. The consequence of information changing managerial thinking means realized strategies do not often correspond with the initially projected plans. Furthermore, some strategies may remain unrealized, having been proved unfeasible and needing to abandoned (Patrizi et al. 2013).

Figure 7.2 Emergent strategy development and revision

Playbook Guideline 54: Where technological entrepreneurial strategies exist, these will usually have evolved over time on the basis of organizational learning

Market Learning

In those cases where the entrepreneur is totally focused on proving the technical viability of their idea, the situation may exist where there is no understanding of potential market opportunity. Hence, this knowledge will only arise once the new product or service is launched, at which point, preliminary answers are generated to the key questions of (i) Who is the customer?, (ii) What benefit do customers seek?, (iii) How does a customer become aware of the new goods?, and (iv) Through which channel is the item purchased?

It is unlikely that a large existing firm would wait until market launch before seeking some understanding of the market opportunity. This is because the senior management recognizes that the potential risks associated with developing a new technology demand some form of market assessment prior to approving any major investment to progress a new entrepreneurial idea. Some firms will tend to rely upon utilization of the “stage gate” model where an assessment occurs as a sequential process constituted of the seven components of idea generation, idea screening, concept development, business planning, prototype development, test marketing, and market launch (Cooper, Edgett, and Kleinschmidt 1997).

In their evaluation of the benefits of utilizing the stage gate model in the case of entrepreneurial products, Millier and Palmer (2001) noted the model involves making certain critical assumptions. These are that the product can be characterized as having features or benefits, which potential customers can understand, and that the market for such a product is readily identifiable. They opined that successful determination of market opportunity is the lowest when firms are engaged in seeking to determine market opportunity for technology-based, new-to-the-world ideas. This is because the newness of the technology means that respondents to conventional market research activities, such as interviews or surveys, will have minimal understanding of the nature or benefits of the proposition being described. Under these circumstances, the large firm may have to rely upon internal opinions, external experts, or other members of the supply chain to offer judgment-based opinions, which may or may not be correct (Evans and Johnson 2013).

Playbook Guideline 55: Understanding of actual opportunity for a radical entrepreneurial idea often can only be achieved by gaining experience from an initial market launch

Strategy Validation

Validation of a technology-based entrepreneurial (TE) strategy is often associated with organizations further evolving their strategizing through either market success or failure. It is not unusual for the selected TE strategy to require changes in the pattern of decision making within the organization. In some cases, the new strategy demands the creation of a radically different organization.

A key objective of the TE strategy is to achieve a close fit between organization and the prevailing market environment. Where achievement of fit is deemed unlikely, then the TE strategy may require the organization moving to a new market environment more conducive to sustaining future performance. Although entrepreneurial behavior is usually presented in the literature as a proactive process, the antecedents may be rooted in a reactive response to an adverse situation, such a sudden deterioration in financial performance. In this latter scenario, the aim of moving to a TE strategy is to support a “turnaround” in order to sustain long-term organizational viability (Piercy, Cravens, and Lane 2010).

Lumpkin and Dess (1996) suggested the dimensions that usually constitute a TE strategy; they are an entrepreneurial orientation, innovativeness, risk taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness. Dess et al. expressed a similar view, positing that evolving a TE strategy represents a distinctive process that is characterized by experimentation, innovativeness, risk taking, and proactive assertiveness. In order to construct an effective TE strategy, the organization will need to assess the potential impact of the three key variables, namely market opportunity, viable technology, and internal capability.

In the case of consumer branded products, such as detergents or coffee, the low-tech nature of these goods means radical entrepreneurial innovation is rarely feasible (Chaston 2016). As a consequence, associated marketing conventions will remain unchanged for many years. This situation causes companies to focus on the use of conventional strategies and processes to defend their market position. In theory, such firms could consider other forms of entrepreneurial activity in relation to their marketing mix or organizational processes.

A very different scenario, however, is faced by companies operating in high-tech sectors such as information technology (IT) or electronic communications. This is because the rapidity with which new technological advances occur means that to survive, organizations must be capable of responding to the reality that existing conventions are difficult to sustain over the longer term. As a consequence, technological advances often result in existing industry conventions being broken.

In relation to the TE strategy, both exploration and exploitation have emerged as the twin concepts in relation to determining competitive advantage and organizational survival (Gupta Smith and Shalley 2006). Kollmann and Stöckmann (2014) posited that most firms would implicitly favor exploration because this permits swift movement toward identifying new opportunities. This attitude is especially prevalent in volatile markets because of the risks associated with allocating scarce resources to any exploitation of any of the identified potential opportunities. Exploration and exploitation are not mutually exclusive activities because very successful companies are likely to pursue both types of activities. Nevertheless, as demonstrated in Table 7.1, the two approaches exhibit very different attributes.

Firms engaging in exploratory innovation may obtain positive performance outcomes, such as discovering new competences, and products that can shape the rules of competition in ways that rivals will find difficult to imitate, thereby leading to unique selling propositions and enhanced customer satisfaction. Firms that shun exploration risk can become vulnerable to the effects of obsolescence because their continued involvement in saturated markets may lead to diminishing financial return. Exploitative innovation is also essential because firms that ignore this activity may run the risks of expending funds on experimentation, without gaining any real benefits. Hence, exploitation is necessary in order to realize positive returns on investments in entrepreneurial innovation through outcomes such as increased efficiency, cost reduction, and superior delivery of customer needs.

Entrepreneurial innovation can facilitate differentiation from competitors. Differentiation can be achieved by exploration through developing creative new offerings to satisfy customer needs. Exploitative innovations such as efficiency improvements or cost reduction can facilitate negation of competitor offerings based on superior value claims. The risk with an organizational focus on internal stability that originates from past success may lead to structural and cultural inertia. This can be an obstacle to change when there is a major shift in environmental conditions (O’Reilly and Tushman 2011). In rapidly changing environments, avoiding organizational inertia is of utmost importance because past organizational strengths can become future liabilities (Danes 2013.

Table 7.1 Innovation typology and attributes*

Exploitative innovation |

Explorative innovation |

• Incremental change |

• Radical or disruptive change |

• Incremental innovation |

• Radical or disruptive innovation |

• Existing business |

• Future or emerging business |

• Short-run perspective |

• Long-run perspective |

• Operational focus |

• Strategic focus |

• Existing technologies |

• New technologies |

• Certainties |

• Uncertainties |

• Efficiency |

• Adaptability |

• Mechanic structures |

• Organic structures |

• Conventional |

• Entrepreneurial |

• Stability |

• Change |

• Sustaining advantages |

• New advantages |

• Convergent behavior |

• Divergent behavior |

Source: * Modified from Simsek et al. 2009.

Ambidexterity involves the dual management of seemingly opposing tasks, which involves the ability to switch to different operational modes when pursuing entrepreneurial innovation. Successful ambidextrous organizations are able to integrate exploitative and explorative activities with the aim of excelling in the present and in the future. Examples of large existing corporations that have been successful in building an ambidextrous capability include GlaxoSmithKline Seiko, Hewlett-Packard, and Johnson and Johnson (O’Reilly and Tushman 2011).

Ambidextrous innovation management is often necessary because the organization faces two forms of environmental changes, namely environments evolving incrementally requiring a need for efficiency enhancement and discontinuous changes demanding radical innovation. The latter is usually mandatory in high-tech industry sectors where there are very short PLCs. This situation caused Kollman et al. to posit that entrepreneurial companies in innovative industries are more likely to manage growth ambidextrously than entrepreneurial companies in low-tech industries.

Ambidextrous organizations require a senior management orientated toward supporting both exploitative and explorative activities. O’Reilly and Tushman noted that some organizations, although aiming explicitly at the attainment of both goals, face the danger of failing because of an inability “to play two games simultaneously.” Entrepreneurial activities need to be organized by building loose and adaptive organic structures with a culture that emphasizes risk-taking, speed, flexibility, and experimentation. In relation to achieving a balance between different activities, structural ambidexterity ensures effective operation of exploitative and explorative tasks by organizing these into different innovation streams. Interaction between all areas of the organization is important to sustain knowledge flows and to permit everybody to understand what activities are occurring elsewhere within the organization. It is vital that those engaged in radical innovation do not encounter internal organizational resistance from the more conventionally orientated areas of the operation.

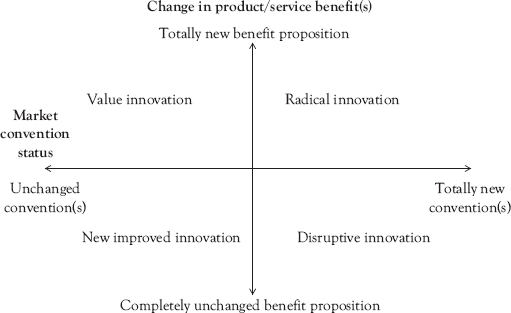

Figure 7.3 Alterative innovation propositions

One approach to determining the degree of entrepreneurial innovation associated with the observed strategies of organizations is to classify outcomes in relation to the dimensions of (i) scale of breaking with existing market conventions and (ii) the degree to which the benefit proposition has been changed. As summarized in Figure 7.3, this taxonomy generates four possible outcomes.

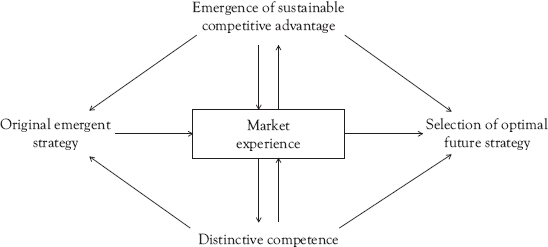

As new entrepreneurial ventures gain understanding from their experience of market conditions, this can lead to recognition of the need to review issues such as the viability of the selected competitive advantage and the distinctive competences required to sustain ongoing success. As summarized in Figure 7.4, these interactions may result in the identification of an optimal future strategy too. Essentially, what will often occur is a reallocation of internal resources to achieve closer alignment with the aim of creating a sustainable competition advantage. This process has been described by Teece (2007) as permitting (i) sensing and shaping opportunities and threats, (ii) seizing opportunities, and (iii) maintaining competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting, and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprises’ intangible and tangible assets.

This need for re-evaluation and reconsideration of the emergent strategy has been described by Burgelman and Siegel (2008) as the “stretching of the rubber bands.” This term reflects the fact that proposing a change can be the cause strategic dissonance between senior management and the employees, where is the need to revise assigned roles and development projects. To gain further understanding of the issues associated with rubber band stretching, Burgelman and Siegel took a case-based analysis of the activities of a number of American high-tech ventures. Their research revealed that while well-managed established companies, such as Intel and GE, have developed a disciplined strategy-making process that can accommodate changes caused by gaining market experience, new high-tech ventures often do not immediately adopt such processes. This is because, during the early days of the venture, the primary focus is on proving the feasibility of a new technology and/or the viability of a new product. As a consequence, these latter organizations often have benefited from earlier understanding of the strategic implications of their core technological invention in relation to both strengths and potential weaknesses.

Figure 7.4 Strategy re-alignment

Playbook Guideline 56: Long-term technological entrepreneurial success is usually dependent on involvement in both explorative and exploitative innovation

Business Models

The complexity of many markets and the risks associated with developing and launching a product based on exploitation of entirely new technology has, in recent years, led to the emergence of the concept that to reduce risks, as part of the emergent strategy development process, organizations should create a business model to define all of the variables associated with managing a market system. Morris, Schindehutte, and Allen (2005) proposed that a business model is a concise representation of how an interrelated set of decision variables in the areas of venture strategy, architecture, and economics are addressed to create sustainable competitive advantage in defined markets.

Definition of an appropriate business model can assist in identifying key factors such as the value proposition, target market, revenue model, partner network, internal infrastructure, and processes. By rethinking and reconfiguring these elements, the technological entrepreneur may be able to identify a new approach that can provide the basis for a new model that confers a competitive advantage. An effective illustration of this approach is provided by Jeff Bezos who sought to exploit the Internet and used the technology to create the highly successful online retail venture, Amazon.

Chesbrough (2010) opined business model development as being a constant experimentation and adjustments to changing market environments. Schoen et al. (2005) proposed the process of business model development as a transitional phase between the invention and the innovation stage, thereby implying that the process of business model development for the commercialization of innovations is a fundamental aspect within the innovation process. Dmitriev et al. (2014) undertook a case-based study of three technological start-ups and one technological spin-off. Despite the nature of the technological innovation across the four firms being unique and highly context-dependent, the researchers noted similar processes of interactions and cycles in business model development within all four firms. The process of business model development appeared as a cyclical, continuous process of conceptualizing value through the activities of market segmentation, value proposition, and the revenue modeling, and organizing for value creation involving cost and revenue estimation, finding equipment, resources and partners to permit collaborative innovation.

Playbook Guideline 57: Development and utilization of a new business model can enhance the chances of achieving technological entrepreneurial success