Technology: The Wealth Generator

The Wealth of Nations

For thousands of years, wealth generation was based on trade or invading other countries and repatriating their wealth. This economic model was changed forever during the first Industrial Revolution. This occurred because technological entrepreneurs demonstrated that the creation of new forms of motive power and the development of new machines could move a nation from an agriculture-based economy to one centered around factory-based, large-scale manufacturing.

Industrialization cannot prevent the occurrence of economic cycles with periods of rising prosperity followed by economic downturns and rising unemployment. Factors that influence these cycles are (a) the belief that ownership of a specific asset would always lead to ever-increasing wealth, (b) the assumption that future income or gain in the value of assets would permit debt repayment, and (c) imbalances emerging between supply and demand. Evidence of the ongoing truism of economic cycles has recently been illustrated following the onset of the global downturn that commenced in 2007, from which many countries have yet to recover.

The catalyst for the weakened state of the global economy was the subprime mortgage fiasco in the United States where financial institutions approved loans to individuals who lacked the income sufficient to service the debt they had been persuaded to assume. As the scale of the problem became apparent, financial institutions either failed or had to be rescued by government intervention. Similar problems also emerged in Ireland and United Kingdom. These events were followed by recognition that in some countries in Europe, such as Greece and Spain, the level of public sector expenditure had become unsustainable. The outcome was the sovereign debt crisis that has been a massive burden dragging down the entire European Union (EU).

Meanwhile, multinational companies in sectors such as coal, oil, and minerals continued to invest in capacity expansion on the false premise of continued rising growth in the Chinese economy. When the first signs of a slowdown emerged in the Chinese economy, a massive decline in commodity prices was triggered. This had a devastating impact, especially in those countries reliant upon commodity exports as their primary source of economic growth and stability.

Even Milk Can Be Risky

White Gold

Case Aims: To illustrate the risks associated with an over reliance upon agriculture

New Zealand’s economy has been highly reliant upon agricultural output. Since World War II, dairy farming has become the dominant agricultural sector. A key problem is the country’s remote location relative to overseas markets, and milk is a highly perishable product. This situation led to the creation of Fonterra that was granted a near monopoly over the purchase of milk and assigned the task of using milk as a raw material to move the country further up the food industry value chain (Baldwin 2015).

Although raw milk production in New Zealand has risen dramatically, Fonterra’s success in moving into branded goods has been limited. As a consequence, the strategy of the company has been to invest in expanding the capability of converting raw milk into milk powder. This is essentially a commodity product, and hence, profit margins have remained relatively low.

New Zealand’s reputation for high quality has proved important in exploiting the growing demand for milk powder in China. As the Chinese economy continued to expand, New Zealand enjoyed a period of unprecedented economic growth. Furthermore, the country’s conservative banking sector practices and public sector spending meant the country was not adversely impacted by the Great Recession caused by the subprime mortgage in the United States and the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. As a consequence, by 2013, New Zealand’s self-perception was of a country enjoying a “golden age” of wealth generation.

Fonterra’s success relied upon rising market demand and minimal milk powder capacity expansion elsewhere in the world. In recent years, other countries have expanded milk powder production capacity in seeking to obtain a foothold in Asian markets. Further price competition emerged when the EU banned exports to Russia in response to the crisis in the Ukraine, causing more European producers to increase their efforts to develop new markets in the Far East. In 2014, the world milk powder market followed the pattern of other commodity markets of moving from boom to bust. The weakening Chinese economy and competition from elsewhere in the world resulted in a collapse in milk powder demand, with the resultant requirement of Fonterra needing to slash farm-gate milk prices. With dairy products representing almost 25 percent of the total exports and milk prices lower than the cost of production, recognition of the adverse impact of these events was reflected in growing concerns about the debt levels within the farming industry (Gray 2016).

Playbook Guideline 1: Avoid excessive reliance on commodities on the hopes that this offers a source of secure long-term wealth generation

The Importance of Innovation

Organizations that have enjoyed an extended period of profitability tend to become complacent about the future, and over time, operating costs tend to rise. New competitors, often based overseas, are not only assisted by rising costs within the incumbent firms, but are also often able to exploit advantages, such as lower labor or raw materials costs, thereby permitting them to compete on the basis of much lower prices (Nuvolari and Verspagen 2009).

Alert organizations are aware that standing still is a guarantee for moving backward. To avoid this outcome, these organizations have to accept the importance of sustaining investment in innovation. It can be considered that there are three dimensions to innovation. These are (1) product versus process, (2) radical versus incremental, and (3) competence enhancement. Product innovation results in an improved or new product or service proposition. Process innovation activity results in improving the effectiveness and efficiencies of production (Datta, Mukherjee, and Jessup 2015).

A long-established management philosophy is that, higher revenue comes from maximizing the retention time for products or services within the maturity phase of the product life cycle (or PLC). The means many firms focus on incremental innovation involving the launch of new, improved version of an existing product or service. An attraction of incremental innovation is that the investment costs are usually relatively small and the risk of market failure extremely low.

Another source of innovation is sectoral architecture, which is concerned with the relationships and interactions that a firm has created within a supply chain. A new firm may encounter obstacles in becoming accepted as a member of an existing sectoral architecture. One way of overcoming this problem is by creating a new, radically innovative alternative architecture. Such was the case with Michael Dell. At a time when other personal computer (PC) manufacturers were using either a sales force or a network of distributors to generate sales, he entered the market by using direct marketing and mail order to service customer needs. Over time, Dell has continually sought to add competitive advantage by further developing architectural innovation and has created a distinctive global, virtual supply network (Lawton and Michaels 2001).

Playbook Guideline 2: Risk minimization and minimal investment in innovation generates minimal financial returns

Detergents Facing an Emerging Risk?

Case Aims: To illustrate that even in low-tech sectors, the unexpected may occur

In a world increasingly concerned with adopting a more sustainable orientation toward the consumption of energy and natural resources, an obvious target for change is the humble washing machine. Interest in how to reduce water and energy consumption led researchers at Leeds University to examine the potential of using a large number of small nylon beads to fulfill the cleaning action within a washing machine.

The researchers discovered that by adding only a small amount of water sufficient to dissolve the stains on clothes and temporarily alter the molecular structure of the polymer beads, which gently rub against the materials being washed, it was possible to reduce water usage by 70 percent. Furthermore, the reduced water usage means that compared to conventional machines, as there is no longer a need for a rinse or spin cycle, energy consumption can be reduced by up to 98 percent, and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions reduced by approximately 40 percent. This breakthrough, which may become a problem for manufacturers of conventional washing machines, may possibly have even greater significant long-term adverse implications for the multinationals that currently dominate the global market for detergents.

To exploit the new approach to laundering clothes, spin-off company named Xeros Ltd has been created to market the technology (www.xeroscleaning.com). Led by CEO Mark Nichols, the company is seeking to refine every aspect of their polymer bead cleaning system in areas such enhancing bead absorbency and upgrading the efficiency of washing machines that utilize the new technology. To assist ongoing developments, the firm has entered into a partnership with BASF, the world’s largest chemical company, to investigate alternative bead chemistries for use in washing machines and custom-tailored detergents.

Playbook Guideline 3: Avoid complacency because in the end, everything has the potential to be impacted by unforeseen changes

Innovation

Radical innovation generates entirely different new products, services, processes, or delivery systems. As demonstrated by firms such as Apple and Google, the reward is exceptionally high profitability. Radicalness is a function of uniqueness when compared with currently available market offerings or production processes. The most radical innovations are new to the world and differ massively from existing products, services, or processes. In contrast, incremental innovation involves adaptations and refinements to existing products, services, processes, or delivery systems (Burgelman and McKinney 2006). Once an organization has successfully launched a radical innovation, this same organization will usually seek to sustain market dominance by also engaging in incremental innovations. An example is provided by Microsoft, which having radically altered the approach to the provision of computer software for PCs, has subsequently sought to retain market leadership through successive releases of the new Windows operating systems and the firm’s suite of Office software products.

Playbook Guideline 4: High-risk radical innovation offers the reward of much greater financial return

Retaining Leadership in the Innovation Stakes

Case Aims: To illustrate that technological innovation demands a long-term commitment to retaining market leadership through superior capability

In the 1920s, Henry Ford revolutionized the car industry by introducing production processes, which he observed in Chicago meat packing plants. His new approach was so successful that a new, rapidly accepted industry convention was established; namely to be successful, a high-volume car manufacturer must be capable of utilizing mass production manufacturing to supply customers with a low-cost, standard product.

Although before World War II some car manufacturers engaged in innovation, this tended to be of an incremental nature, leading to product improvements such as automatic gearboxes, power steering, and hydraulic brakes. Following the end of World War II, price continued to be the critical factor influencing the purchase decision of the average customer. This had the implication that successful firms needed to maximize manufacturing productivity. Less effort was allocated to involvement in innovation. Instead, the primary focus was that of achieving economies of scale. This was usually delivered through industrial mergers between domestic producers, eventually leading to only one or two firms dominating each Western World home markets (e.g., Ford, General Motors in the United States; British Leyland, subsequently Rover Group, in the UK, Volkswagen in Germany; Fiat in Italy, Renault; and Citroen in France) (Helper and Henderson 2014).

The OPEC oil crisis in the 1970s sparked higher customer interest in fuel economy, offering both European and Japanese producers the opportunity to break into the largest car market in the world, the United States. While the U.S. car makers were struggling with the problems of learning how to make smaller cars and manage in what had become a highly unionized production environment, the Japanese were left to experiment with concepts such as robotics, just in time (JIT) to further enhance productivity and total quality management (TQM) to improve “‘build quality.” Their success permitted them to become global players in the world car market. Many of the Japanese’s advances in manufacturing, which took firms such as Toyota and Honda to market leadership, were often achieved by being willing to challenge industrial conventions established by the major Western manufacturers (Townsend and Calantone 2014).

Long lead times can exist between concept identification, completion of fundamental research, and the ability to launch a new product based on a new technology. An example of being prepared to invest in the acquisition of new knowledge and internal capabilities is provided by Toyota. Long before the American or European car manufacturers exhibited any concerns over rising oil prices, Toyota, as the world’s leading automobile manufacturer, had the strategic insight to research how to move vehicle transportation away from a dependence on hydrocarbons to utilize other types of fuels. Their first product was the highly successful hybrid the Toyota Prius. Having launched the Prius, the company has focused on continuous innovation to improve this vehicle and to expand the company’s hybrid product line (Rapp 2007).

The expected next alternative to cars using petrol is the fuel– cell vehicle, or FCV. These vehicles run on electricity generated by combining hydrogen with oxygen, with only water vapor being the byproduct. Two major constraints, similar to the initial hurdle facing electric cars, are the high development costs and the lack of refuelling infrastructure. Toyota’s solution has been to offer its fuel cell components and FCV patents and patents for the installation and operation of hydrogen fuelling stations to others companies free of charge until 2020. Although the move risks Toyota compromising its technological leadership in the FCV technology, the decision is perceived as less important than the need to stimulate an industry-wide effort to rapidly expand the infrastructure required to achieve rapid market penetration for the new technology. Toyota’s decision comes ahead of the launch of its new fuel–cell sedan, the hydrogen-powered Mirai, in the United States and Europe in 2015 (Muller 2015).

Playbook Guideline 5: Staying ahead requires an ongoing commitment to engaging in radical and incremental innovation

Entrepreneurship

French economist Jean-Baptiste Say is credited with inventing the term “entrepreneurship” in the early 19th century. At the time, the concept was not seen as important by mainstream economists (Dorobaţ 2014). It would not be until the 1920s that the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter challenged the classic economic theory and proposed an alternative paradigm for explaining fundamental economic change. Schumpeter (1934) noted that profits decline when technologies mature and the emergence of new technologies permit new winners to emerge. He described this process as “creative destruction,” in which entrepreneurs exploit a new technology as the basis for the creation of entirely new industries, while concurrently existing, mature industries become increasingly unable to sustain wealth generation.

Schumpeter’s primary focus was on entrepreneurship in which a new technology, often during an economically turbulent period, provides the basis for new businesses, and that as a result of creative destruction, this become a nation’s new primary source of wealth generation. Subsequently, Schumpeter (1954) concluded that existing larger firms are less likely to engage in creative destruction. Instead, they tended to engage in “creative accumulation” by exploiting their accumulated knowledge in the development of the next generation of products and services. This scenario can be contrasted with creative destruction, which involves a widening of innovation by new firms entering the market and successfully challenging incumbents by exploiting new forms of technology.

Playbook Guideline 6: Creative destruction permits the development of new to the world products and the creation of new sectors of industry

Israel Kirzner (1973) rejected Schumpeter’s perspective that entrepreneurs develop new propositions without initial reference or influence of market forces. Kirzner’s viewpoint was that entrepreneurs are engaged in moving resources from areas of low productivity to a different area where profitability had the potential to be much higher. The catalyst for action is the entrepreneur being alert to new market opportunities that can be exploited through some form of innovation. This is in contrast to Schumpeter perspective. He did not see entrepreneurship as a demand-driven process, but rather it is entrepreneurship that forces changes in output and consumer tastes.

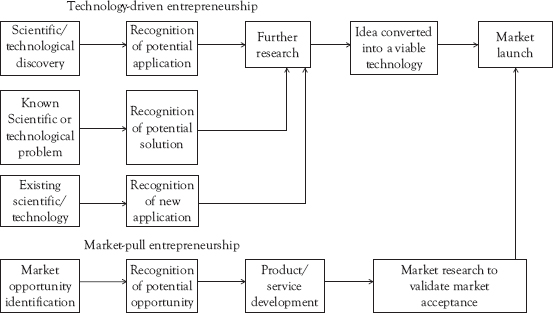

Available evidence seems to indicate that both Schumpeter and Kirzner’s perspectives are equally valid. This perspective can be seen in the distinction made between technology-driven versus market-driven entrepreneurship (Habtay 2012). Technology-push entrepreneurship occurs where scientific breakthroughs and R&D experimentation precede market opportunity analysis and the development of a viable business proposition. In contrast, market-driven entrepreneurship begins with the customers creating demand pressure, thereby permitting identification of new market opportunities that provide the basis of innovation that precedes a firm’s investment in product or service development activities. This latter form of entrepreneurial change typically emerges when a market often originally created as the result of disruptive technological entrepreneurship has matured and market-driven entrepreneurship based around a revised business model becomes a more likely strategy for sustaining ongoing success.

Habtay proposed that the start point for market-driven entrepreneurship is the discovery of viable new customer value propositions and the identification of a viable customer segment. The other dimension is a market structure that permits the creation of a business model that permits the focal firm to effectively exploit the identified market opportunity. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, in the case of technology-driven entrepreneurship, it is new scientific or technological knowledge that results in a push for development, eventually leading a commercially viable outcome. Market-opportunity entrepreneurship can be considered as a pull-directed process because recognition of potential customer need is the catalyst that prompts the development activity. It should be recognized, however, that in responding to market pull, exploitation of new scientific or technological knowledge may be required to create a viable commercial solution.

In considering which of the two options, market-driven or technology-driven entrepreneurship, offers the greatest source of long-term wealth generation, both history and the current day evidence clearly indicate the superiority of the latter philosophy. The first Industrial Revolution generated huge wealth for the UK entrepreneurs involved. Similarly, the second Industrial Revolution, which centered around the exploitation of electricity and the internal combustion engine, made individuals such as Thomas Edison extremely rich. Today, during the third Industrial Revolution, which is focused on exploiting the Internet and related technologies, the world’s two most valuable companies, in terms of their traded share values, are Apple and Google.

Figure 1.1 A comparison of entrepreneurial processes

Playbook Guideline 7: Individuals and organizations seeking to maximize long-term wealth should focus on exploiting technology-driven entrepreneurship

Technology-Based Destruction

Case Aims: To illustrate the technological opportunities offered by Internet-based has created a new “sharing economy,” which can adversely impact existing, long-established service businesses

Advances in computing, the Internet, and the emergence of new technologies, such as the smartphone, can be considered as providing the basis for the latest Industrial Revolution. This situation has led to the emergence of new forms of creative destruction. One form of creative destruction is being achieved by new companies engaged in what has become known as the “sharing economy.” This involves new companies, such as the taxi firm Uber, developing new ways to exploit the Internet and associated emerging technologies to support web platforms that bring together individuals who have underutilized assets with people who would like to rent those assets over the short term (Cusumano 2015).

Uber started life in San Francisco as a private limousine service. In 2010, the company launched a smartphone app that enabled potential customers to call for a ride, get a price quote, and then accept or reject it. The providers of the ride are independent drivers who pay Uber a commission for being linked to customers. The regulations that apply to conventional taxi companies do not usually apply to Uber drivers, and hence, these individuals can provide customers with lower-cost rides in smaller, less expensive cars. To expand their fleet of drivers, Uber helps individual drivers get loans to buy new cars, which permits them to deliver the service. Not required to meet certain regulations for in relation to the provision of transportation services, such as insurance, training of drivers, and licenses means, Uber can outcompete the existing taxi firms. Uber drivers can also decline to provide service when they do not like the requested destination. This is a behavior that existing taxi companies cannot exploit because they are obligated to offer standardized prices and provide service to anyone who calls.

Another example of the sharing economy is provided by Airbnb. This started in 2007 in San Francisco when the founders had extra rooms to rent and decided to offer a low-cost air mattress and bed and breakfast to attendees at a local conference. They created a website to target cities with conferences and signed up people with spare rooms. Subsequently, the company has expanded by offering the service to anybody looking for low-cost accommodation. By September 2014, Airbnb had expanded to 800,000 room listings in 190 countries and claims to have attracted 17 million customers (Helm 2014). Not surprisingly, within the hotel industry, the unions have reacted strongly to this threat by demanding city regulators take action over what may be breaches of regulations regarding private hosting and subletting (Fox 2016). There is also the potential for a major loss in tax revenues in those cities where there are a large number of hotels generating high-level valued-added taxes.

Playbook Guideline 8: Focus on exploiting new or emerging technologies when seeking to radically change long-established industries

Definitions

The Oxford English dictionary defines the entrepreneurship as the activity of an individual who “attempt to profit by risk and initiative.” This is a somewhat broad perspective that many people would probably consider could be associated with broad range of activities, only some of which can be perceived as entrepreneurial. In an attempt to propose a definition that could provide a framework for determining whether an individual or an organization can be considered as being entrepreneurial, Chaston (2016) posited that the outcome of all innovation is some form of change. In the majority of situations, innovation achieves an incremental improvement in a product, service, or process. The magnitude of change does not require any significant behavior shift by customers in order to be able to utilize the innovation. Examples of conventional innovation in the world of branded goods include a detergent that has better whitening power or the addition of new flavors to expand the variety of canned soups that are made available to consumers.

This situation can be contrasted with entrepreneurial innovation where there is a fundamental change in an existing product, service, or process or the introduction of a totally new to the world proposition. In such cases, utilization of the new offering will involve significant education of the potential user to make available new understanding that is necessary to gain widespread market adoption. Even more importantly, entrepreneurial innovation will usually have the potential to replace these existing propositions, in some cases on a scale that renders these latter goods completely obsolete. On the basis of this outcome, Chaston proposed the following definition, namely:

Entrepreneurship is an activity which disrupts existing market conventions and/or leads to the emergence of totally new conventions.

In terms of this current text, the preceding definition provides the following basis for defining the role of technology-driven change, namely:

Technological entrepreneurship is an activity involving the exploitation of a new, emerging or existing technology which disrupt existing market conventions and/or leads to the creation of totally new conventions.

Technological Convention Disruption

Case Aims: To illustrate how an entrepreneurial idea can emerge and evolve over time as the founders gain understanding of the potential for market disruption

At the beginning of the saga that led to the creation of the first Apple computer, Steve Jobs’ primary interest was to eventually start a business. It was his close friend Steve Wozniak who first had the idea of creating a PC. He had already designed a terminal with a keyboard and monitor that could be connected to a minicomputer. His vision was to locate the microprocessor inside the terminal and the idea for a stand-alone computer of PC was created. Having assembled his creation, he developed the code necessary to permit the use of the keyboard to display letters on the computer screen (Isaacson 2011).

At this juncture, Steve Jobs proposed Wozniak’s idea could be used to make money by building and selling the printed circuit boards that could carry a microprocessor, offering eight kilobytes of memory that could be programmed using BASIC. Their first potential customer was Paul Terrell who owned a computer store, the Byte Shop. He was not impressed with the circuit board idea and insisted he be supplied with assembled boards on which the microprocessor was already installed. When Jobs delivered the boards, it became apparent that Terrell had expected a more complete product that included a power supply, case, monitor, and keyboard. Jobs accepted the validity of Terrell’s perspective, which acted as the catalyst for the vision of PCs needing to come in a complete package based on the hardware being encased, the keyboard being built-in, provision of a power supply, and the inclusion of appropriate software. The outcome was the world famous PC icon, the Apple computer. This product successfully challenged and disrupted existing conventions within the computer industry, eventually providing the basis for a new worldwide global product convention.

Playbook Guideline 9: Technological entrepreneurship can create an entirely new-to-the-world proposition or radically change an existing sector of industry

Entrepreneurial Infrastructure

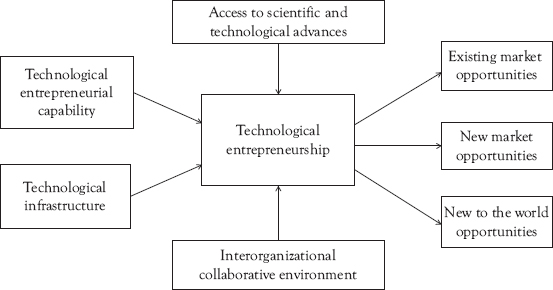

There is a romantic appeal about single entrepreneur or a small group of entrepreneurs laboring away in a garage or university laboratory, which results in a completely new technological innovation and the subsequent launch of a world-beating product or service proposition. Although such events will continue to occur, the frequency can be expected to remain somewhat low. This is because as technology becomes more complex, it is increasingly difficult for an individual or small group of individuals to have the knowledge and resources that are demanded during the development and commercialization of radically new, technology-based propositions. These interactions can be considered as components within a technological ecosystem of the type summarized in Figure 1.2.

The importance of Silicon Valley, California, as a the leading source of entrepreneurial wealth generation is illustrated by the fact that in 2010, the ZIP code 95054 in Silicon Valley produced more industrial patents than any other ZIP code in the United States. Engel and del-Palacio (2011) posited this scale of success of firms can be attributed to the area being the world’s leading “Cluster of Innovation.” The cluster’s ecosystem is composed of start-ups, professional service firms that support the start-up process, and mature enterprises that remain focused on sustaining long-term growth through ongoing emphasis on technology-based entrepreneurship.

Engel and del-Palacio (2015) posited that Silicon Valley, along with other Centers of Innovation elsewhere in the world key are critically reliant on entrepreneurs being supported by an infrastructure constituted of venture capital investors, mature corporations acting as strategic investors, universities, government, R&D centers, and specialized service providers. Developing and exploiting new technology usually demands massive expenditure. In the case of start-ups, a critically important aspect of Silicon Valley infrastructure is the presence of venture capitalists that have both the expertise and “deep pockets” to fund the activities of new, emergent entrepreneurial firms.

Figure 1.2 Inputs and outputs within the technological entrepreneurship ecosystem

Engel and del-Palacio noted that the large companies in the area recognize the importance of investing in new technology, either internally or providing collaborative support for smaller firms. Engaging in this scale of expenditure is only made possible because large companies, such as Apple and Google, have accumulated huge cash reserves that can be made available to fund the commercialization of new technologies. Other infrastructure components that Engel and del-Palacio consider important within a cluster of innovation is the presence of leading, research-orientated universities and research centers funded by governments to engage in blue sky and leading-edge research programs.

Playbook Guideline 10: Technological entrepreneurs can greatly enhance their potential for success by locating within an appropriate cluster of innovation