Chapter One

General Principles of Training Measurement

The first step in this complex topic is to set some ground rules. In this section we will discuss some basic principles that summarize our general findings and recommendations about training measurement. You should consider these principles as guidelines throughout your training measurement journey.

1. Measurement Should Deliver Actionable Information

Before you start to figure out what to measure, you should ask yourself a more fundamental question: why? Why are we measuring training? What is the real purpose? Let me propose an answer:

The purpose of measuring any business process is to obtain actionable information for improvement.

In any business or operational function, measurement is a tool for improvement. It exists for one and only one purpose: to give you specific information you can act upon. Consider the dashboard of your car. It includes highly actionable information: speed, amount of gas, water temperature, number of miles driven, and whether the lights are on or not. You can glance at your dashboard and decide what to do. You should “slow down,” or “get gas,” or “put water in the radiator.” These measures are not particularly high level or exciting, but they are really important and really actionable.

Consider what your dashboard does not include: it does not include the “current market value of your car” or “how good a deal you got at the dealer.” This information, which may make you feel good (or bad), is not actionable. (I would argue that in many cases ROI is one of these.)

Now consider what information about training would be highly actionable. Let us look at measurement areas and the actions we could take based on good measurements:

Program Effectiveness and Alignment. How can continuous improvements be made to the programs, processes, and organization to become more effective and aligned with the business? Did the line managers support this program? Did they have enough input? Did we communicate its goal and structure effectively? Did we market and support it well? Is the program current and topical, given the critical operational issues we face today?

Program Design and Delivery. Which elements in a program work well and which do not? How does our delivery model work well, and where can we improve it? Which instructors or facilities are performing well or poorly? Who in our target audience found it valuable and why? Who did not find it useful and why? Which elements of our e-learning were effective and which were not?

Program Efficiency. How well are we utilizing our financial and human resources? Are we delivering training programs at the lowest possible cost per student-hour? How does the cost per hour of program A compare to the cost per hour of program B? Is it worth the extra cost or not? Are we leveraging e-learning in a cost-effective way? Where can we save money and create higher value for lower cost? How can we continuously drive down the cost of content development and delivery?

Operational Effectiveness. How well are we contributing to our organization’s strategic goals? How well are we meeting our operational business plan1 for learning? Where can we improve our time-to-market, attainment of our training objectives, and alignment with other HR or talent initiatives?

Compliance. If this training is mandatory, who is in compliance and who is out of compliance? What manager or workgroups are out of compliance? When do people have to recertify themselves? What elements of the program have caused any compliance issues? Did we reach our target audience or not? Why not?

Larger Talent Challenges. How well are line-of-business managers completing their training goals? Are compliance programs being met and, if not, why not? How well is training meeting the needs of performance planning and development planning? Are your programs meeting the organization’s needs for skills gaps and strategic development?

These are important questions. In essence, your goal in measurement should be to obtain information that “operationalizes” your training function and gives you, the HR organization, and line-of-business managers the information needed to take action.

Defining the Term “Actionable Information”

Let us define the term. “Actionable information” refers to information that can be used to make specific business decisions. For example: Did the simulation program we developed drive the right level of learning? Should we have had more prerequisites? How cost-effective was this program versus others we delivered? Which components should be kept and which should be discarded? For which audience groups was it appropriate? Which audience groups did not find this program appropriate, and why?

Actionable information can be used to make specific business decisions. Actionable information has three key attributes:

1. Actionable Information Is Specific. To be actionable, the information or data we obtain must identify specific program components, audience groups, audience characteristics, utilization patterns, costs, or effectiveness in a way that can easily be analyzed by audience group, program element, manager, organization, or other specific dimensions. Averages are generally not specific. If the “average satisfaction” rating is low, for example, why is it low? Who rated it low? What groups rated it low? What elements created the low rating?

Specific detailed information typically requires granular data from your learning management system (or other enrollment and registration system). We discuss the importance of implementing consistent assessments and standards in your LMS later in this book.

2. Actionable Information Is Consistent. In order for information to be actionable, it must be consistent from program to program to enable comparisons across programs. For example, to measure learner satisfaction with an instructor, the same scale must be used for all programs to compare instructor against instructor. We found in our research that consistency is far more important than depth. Consistent “indicators” that apply to the programs can offer tremendous actionable information (see section, “How ‘Indicators’ Best Measure Training”).

Note: Throughout this book the term “indicator” refers to some measurement (for example, satisfaction with the instructor, satisfaction with the classroom) that is captured directly from a learner or manager and tends to “indicate” impact, effectiveness, alignment, or other measures. A “measure,” by contrast, is an actual business measure, such as sales volume, error rate, production rate, and so on. The reason we emphasize the use of indicators is that they can be captured in a consistent way from program to program. (In Chapter 6: Measurement of Business Impact, we discuss techniques for capturing and measuring real business outcomes.)

For example, an end-of-course assessment question that asks “How well, on a scale from 1 to 10, did this course help you improve your effectiveness at your current job?” is an indicator of utility. A question such as “How strongly would you recommend this course to others in your department (10 = strongly recommend, 1 = not at all)?” is an indicator of utility or alignment. Neither of these questions actually captures business impact data directly, but they do capture consistent data, which, when captured across thousands of learners and hundreds of courses, will give you tremendously actionable information. Captured as indicators, such data will immediately show you courses that have “high utility” versus “low utility”—even though you have not tried to measure the actual utility itself. A course that scores low in utility would warrant an in-depth analysis of the program elements, audience, delivery techniques, and so on.

3. Actionable Information Is Credible. Finally, to make information actionable it must be believable. That is, you should avoid indirect correlations with business measures that are not 100 percent attributable to training.

Now this principle may be a bit controversial. Many books have been written describing techniques for linking learning to direct business results. While this exercise clearly has value, we have found that in most cases such efforts fall into the category of “projects,” not “processes,” and as you will read later, one of the keys to a successful measurement program is to focus on repeatable processes.

The information you capture must stand up to testing from non-training business people (people outside of the L&D function). If you compute the return on investment (ROI) of a sales training program, for example, and then claim some credit for a resulting sales increase, then be ready to defend that claim. The vice president of sales may feel that the sales increase cited is a result of a great sales team, while the vice president of marketing may believe it is a result of a great marketing program.

Averages May Not Deliver Actionable Information

Another important principle: use caution when employing averages. Average information (for instance, average satisfaction level, average scores) may not give actionable information and can be misleading.

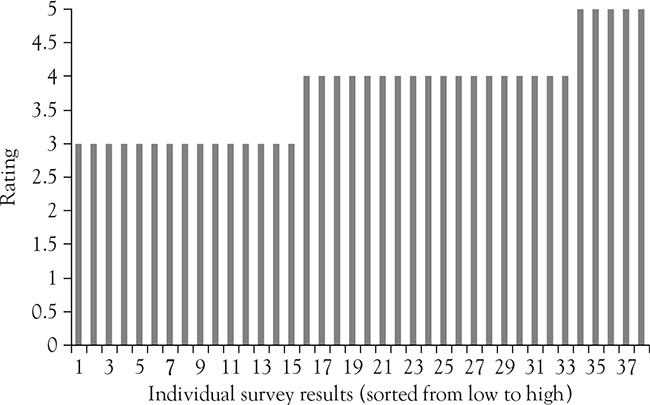

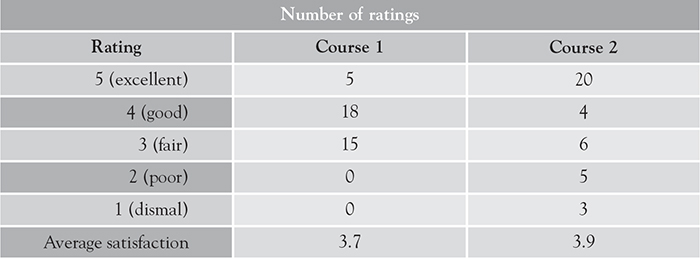

Let us look at a contrived but very realistic example. Suppose the average learner satisfaction rating for one course is 3.7, and for another, it is 3.9 (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2, respectively). Presumably, this would indicate that the second course was of higher value.

Figure 1.1 Course 1. Satisfaction Average of 3.7

Figure 1.2 Course 2. Satisfaction Average of 3.9

Figure 1.3 Comparing Detailed Satisfaction Scores

Using the idea of actionable information, a training manager might then try to figure out what was “wrong” with the first course to identify areas where the first course could be made more like the second course.

Let us go beyond the averages and dive into the data. Figure 1.3 reviews the actual distribution of satisfaction levels shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2. The actual data presents a completely different story.

For Course 1 (the lower-rated course), there were no “1” or “2” low ratings. Although only 13 percent of the learners were “thrilled” with the course, most found it to be “fair” to “good”; 58 percent rated the course “good” to “excellent.” This course is a pretty well rated course.

For Course 2, (the higher-rated course whose average rating rates it the “best practice” course), 60 percent of the learners rated the course between “good” and “excellent,” with half of the learners being “thrilled” and rating it a “5.” Yet, 21 percent of the learners hated the course (rating it a “1” or “2”) and 36 percent gave it a rating of “3” or below. This course had some problems.

Which course is really “better”? The average does not answer this question.

Looking at the detailed distribution of satisfaction ratings tells the real story. The first course is an average course; it more or less gets the job done, and seems to be reasonably well liked. The second course is probably a much better course but demands a more specialized audience. The data shows us that it had a number of the wrong people in attendance; hence, it was poorly “aligned.” (We have an entire chapter on alignment in this book.) The detailed data we have obtained is now highly actionable.

If this was your course you would want to characterize the differences between the people who did not like the course and those who did. Perhaps the people who liked the course are the more senior managers? Perhaps the people who did not like the course were from a certain country? Many actionable findings could be captured from this information.

The purpose of this contrived example is to show why it is so important to “dive into the data” to obtain actionable information. As this example illustrates, detailed data—by audience, by session, by date, by platform—will give you insights you can act upon.

Again, the key to obtaining such detailed data is to create standard measurement indicators and capture them consistently across many programs and many learners.

2. A Measurement Program Should Not Be Designed to Cost-Justify Training

The second principle we would like to discuss is the trap of using measurement to cost-justify training investments or programs. Many times the biggest driver for a measurement program is a mandate from above: “We don’t trust what you’re doing, so we want you to measure the impact.”

“I really need help coming up with a measurement strategy for our leadership development program. Our management continually asks us how much value we are getting out of this investment.”

—Chief Learning Officer, Healthcare Provider

My experience with many organizations has shown that when the focus on measurement to cost-justify training investments, the measurement program rarely results in a repeatable, actionable process. But clearly the problem exists: How do you make sure the organization understands the value of your training? How do you prove its impact?

Let me discuss a few important thoughts here. First, if your training organization is well aligned with the business (and has in place a business plan, the right set of governance processes, and communicates vigorously, which we discuss later), the organization will clearly see value. In fact, if you develop an operational plan for training (and only about half of organizations do this), publish this plan, and transparently communicate your progress against this plan, and regularly enlist feedback, your business constituents will have confidence.

Second, if you do not have the confidence of line management, no amount of measurement will help your case. One of the CLOs we interviewed told me how he manages this process. He regularly interviews line executives throughout his organization and asks them, “Do you believe that organization development will help us to attain our business goals?” If they say yes, then he knows they will appreciate the value of his programs. If they say no, then he knows that no amount of ROI analysis or other impact analysis will convince them. Bottom line: Do not design your measurement program to cost-justify training.

Third, consider how other operational groups in your organization measure themselves. Does the IT department try to cost-justify every IT project? Does the facilities department cost-justify every facilities investment? Trying to cost-justify training spending is just as hard and uncertain as trying to cost-justify other business support functions, such as marketing, finance, facilities, and IT. These business functions add value by supporting the revenue-generating, customer-serving, or product-development organizations in the company. While these functions do not directly generate revenue or manufacture products, their value must be measured through their indispensable support, alignment with strategic initiatives, high levels of customer service, and contribution to the overall business strategy.

Think about how your IT department measures itself. Does it measure the ROI of the company’s email system? No, that is assumed. The IT department measures the system uptime, how much it costs to operate, how well the data is protected, and how easy it is to use. These operational metrics are very useful and actionable—they tell the IT department what it must do to continuously improve. Does the organization talk about eliminating the IT department? Rarely—only if the IT department is not providing high levels of customer service and support of strategic business initiatives.

Consider the marketing department. Like training, marketing is used to influence behavior, which ultimately results in sales. Although the influence, alignment, and cost-effectiveness of marketing can be measured, organizations cannot directly measure its direct contribution to the bottom line. Marketing, like training, is measured by its operational efficiency, alignment, and other indicators that drive business results. Marketing measures its return to the business by looking at indicators: leads generated, hits to the website, or inquiries from direct-mail campaigns. Training is very similar.

3. Measure Training as a Support Function

The third important principle in measurement is that training is a business support function. As a support function, training exists solely to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of what we call “line of business” or “revenue and customer” functions. Consider Figure 1.4.

In any business there are two types of organizational groups: those that directly build products, generate revenue, or support customers (called “line of business functions” above)—and those that support these customer and revenue-generating groups (the horizontal boxes). Sales, manufacturing, customer service, and other customer-delivery organizations fall into these line-of-business, customer facing groups. HR, IT, Finance, Facilities, and so on, all fall into the second category. These support groups exist in order to improve the performance of the true revenue and customer-facing operational groups.

Figure 1.4 Training as a Business Support Function

What each type of organizational group should measure is different. Sales, customer service, and manufacturing should measure true business or customer output: dollars of revenue, number of cases closed, customer satisfaction, and number of units produced. Support groups, then, do not directly measure their direct impact on sales, customer satisfaction, and manufacturing quality—but rather how well they support these functions and their initiatives to drive outcomes. Although this may sound subtle, consider the following example.

Imagine that one of your business units (U.S. Sales, for example) tells you that their goals are to gain market share in the mid-market business segment by 30 percent through the launch of product A. Your goal in training is not to increase market share, but rather to support this group’s goal of increasing market share. When you sit down with the executives of this group, you may find that they demand the following: new training to be delivered within 30 days of product launch, learner satisfaction of 4.5 or higher, a total training time of two days or less, a cost of $1000 or less per learner, and 90 percent adoption rating within 3 months.

Your goals and related measures, then, fully align with theirs. Your measures, as shown in Figure 1.5, are highly aligned, actionable, credible, and detailed. They fit our three criteria for actionable information. They are also very easy to capture.

If you sat down with the line business executives and established these criteria for success, you would find yourself very well aligned with their business goals.

Let’s go back to the concept of an indicator. If you deliver a program that is delivered on time, on budget, with high satisfaction and utility indicators (more on this later), and excellent alignment with the business’s known business initiatives, you will definitely see business impact. And the business leaders will be thrilled. If you also measure your internal efficiency and cost-effectiveness, you will be even more highly regarded.

Figure 1.5 Alignment of Learning Objectives with Business Objectives

Throughout our research we found highly effective training organizations that measured only a few things—but they were the things the business really cared about. They did not focus on trying to measure “level 2” or “level 3,” except for highly exceptional, very expensive programs (such as leadership development) where the investment in evaluation is worth the effort.

Later in this book, we highlight many ways of using indicators to measure direct business impact (see Chapter 5: Implementation: The Seven-Step Training Measurement Process). In fact, our research finds that most well-aligned training organizations have dozens of measures of direct business impact.

Let us cite another example of how valuable these support indicators can be. One of the most successful retailers of home improvement supplies has developed a broadly deployed e-learning system that delivers courses to 120,000 employees through in-store kiosks. The courses delivered include programs on safety, loss prevention, new-hire training, and many types of product training (for example, lawnmowers, drills, saws, wood, and so on).

At the store level, the managers have a set of graphical, easy-to-read reports that display completion rates and total training compliance. This information is highly actionable at the store, regional, and divisional levels. This “exception reporting” tells managers which employees have not taken training or are behind on their training targets. Does it measure business impact? Not at all. Is it a key indicator of success? Absolutely.

The manager of this particular training organization periodically asks the retail managers about the value of the training. The answers he receives are invaluable: “We can get new hires up and running in only a few days.” “Our training program is one of the most valuable tools we have for retention.” It turns out that in retail (and many other industries) one of the biggest values of training is not sales productivity but retention. Training makes individuals feel more confident, which in turn increases their engagement and commitment to the company, which in turn increases their loyalty and productivity. Can this be measured directly? No. But can you obtain indicators of this success by talking to managers and looking at aggregate retention rates? Absolutely.

4. A Measurement Program Must Meet the Needs of Multiple Audiences

The fourth principle of training measurement is that you must consider the information needs of different audiences. Different audiences will expect and demand different levels of information.

The CLO and training leaders will be interested in efficiency, effectiveness, resource utilization, and on-time delivery. These measures should be developed in a way by which they can be benchmarked, and the measures should give specific detailed information that can be used to change and improve training operations.

The vice president of HR will be interested in training volumes, compliance, and spending per employee. These measures should be computed annually or quarterly, and compared against industry benchmarks.2

Line-of-business executives will be interested in how much training was consumed, which employees are and are not taking training courses, and how well the employees and managers feel their needs are being met. These executives are interested in measures such as scores, completion rates, satisfaction levels, alignment, and indicators of utility and impact.

First-line managers will want to see detailed results from their employees to help with development and performance planning. The managers want specific information on completion (exception reporting), utility, and learning results.

Trainers and instructional designers will want to see specific comments and feedback from learners on the quality and value of their particular programs. Comments and direct feedback must be captured and distributed on different program elements.

Each of these needs has value, and each requires a slightly different level of detail and way of presenting information. As you develop your measurement process, think about what is needed for each of these audiences, so that you capture information of value to the entire organization. By serving the needs of line managers and other executives, you have naturally created alignment. They will tell you what they need to know, which in turn helps you to improve your training organization to meet these objectives.

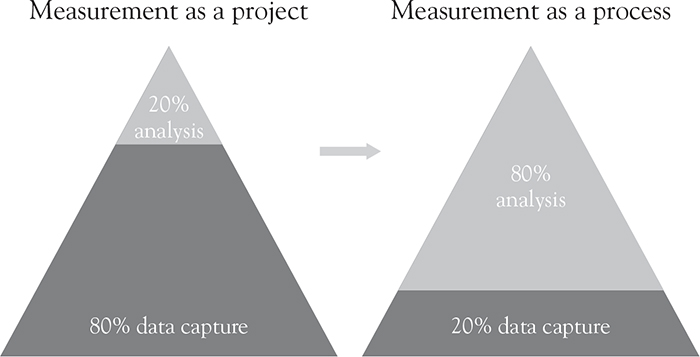

5. Measurement Should Be a Process, Not a Project

If you want an ongoing measurement program, you should not think about measurement as a series of “evaluation projects,” but rather as an operational process that captures continuous, actionable information. There is a cost to measurement: it takes time, energy, and tools. Successful high-impact organizations focus on developing a simple, easy-to-implement, repeatable process that can be used over and over again. What our research has found is that less data, measured in a repeatable and consistent way, is far more valuable than a small number of highly complex, custom measurement projects. When you find extraordinary information (for example, a program that is failing miserably or a very expensive program that is not meeting expectations), then you can embark on one or two evaluation projects.

Consider Figure 1.6. If you let program managers try to measure the efficiency, satisfaction, and impact of their programs through individual, program-oriented evaluation projects, the workload would look like the triangle on the left. You will spend a lot of time and energy focusing on data capture, leaving little time and energy for analysis. You may be able to standardize the evaluation process, but you will find that you do not have enough time or resources to cover all your training needs and likely will spend far too much time capturing information to really analyze it well.

Figure 1.6 Measurement as a Project Versus Process

On the other hand, if you implement a simple but repeatable process that crosses all of your programs, the workload will look like the triangle on the right. And if you use approaches like the ones in this book, the information you capture will be very detailed and will cover all elements of the program, from design through delivery and impact. By thinking “process” versus “project” then, you will find yourself asking “What can I measure that will apply to all our programs,” rather than “What can I do to evaluate a single program.” The result will be a highly efficient and actionable set of data that will help you decide when, if ever, you want to embark on an individual evaluation project of a single program.

In the quest of such a process, consider the value of measuring the same indicators across all training programs. If you did establish eight to twelve standard indicators for all learners and all managers in all programs, you would quickly start to see wide variations among programs, instructors, media, audiences, program types, and more. You would be able to compare the outputs and efficiency of programs against each other. You would be able to show line management and other managers how your programs are improving over time. And you would be able to quickly see “outliers”—programs that are highly effective or efficient when compared to others. You will learn more about how to do this when we discuss the Impact Measurement Framework®.

How do you establish standard measures? As Figure 1.7 shows, best-practice organizations typically develop three sets of standard indicators or surveys: first, the standard indicators for all learners in instructor-led training. These questions will typically include questions about the facility and instructor, in addition to impact questions from our framework. Second, they develop a set of standard questions for learners at the end of an e-learning or blended program. These differ slightly because of the delivery media. Third are a standard set of questions for managers, which reflect alignment, utility, and other impact measures. We will describe these three sets of questions later in this book, but for now it is important to understand the principle of thinking “process” not “project.”

Figure 1.7 Standard Indicator Sets to Consider

Assign a Process Owner

An important step in creating this measurement process is to assign one person or one group to own the development, monitoring, and reporting of the process. Our High-Impact Learning Organization3 research found that organizations with a single person (or small team) who owns the measurement process are as much as 11 percent more efficient in their overall training operations. Each program manager cannot be asked to define his or her own way of measuring a program—measurement is a specialized process that takes focus. Each program manager should implement the process, but the process itself should be defined and monitored by a single person. This person can then train program managers in its implementation, analyze data across programs, and evaluate results.

This measurement person or team can focus on the following important questions:

• What are the goals of this measurement strategy? What decisions do we want the data to support?

• What operational plans do we have in our training organization that we should measure and monitor?

• What operational measures and plans exist in the business units we support that we can align our measurement toward?

• How can our measurement process be made consistent from program to program?

• How can we make it easy to scale, without increasing numbers of staff required as we roll it out through more and more programs?

• How can we make the process easy to administer and drive a high level of compliance with the survey or other tools used to capture data?

• How can the data be stored so that it is easy to recall in the future and compare against new data? What analytics or LMS system will be best for capturing and analyzing this data?

• How can we most easily report and analyze the data we capture?

• Make sure the measurement approaches are “repeatable processes” and not “projects.”

Measurement Versus Evaluation

There is a difference between measurement and evaluation. “Measurement” (as discussed in this book) provides the information and data for analysis. This data can be used to monitor, analyze, and evaluate every step in the learning process.

“Evaluation” refers to a process used to judge or determine the relative value of a given learning program. ROI analysis, for example, is a form of evaluation (not a form of measurement).

This book is focused on helping you implement a measurement program—describing repeatable processes you can implement across any program. If you follow the steps in this book, you will find it easier to decide when, if ever, you embark on specific evaluation projects. It is important to consider any form of evaluation in the context of a “model”—that is, a repeatable approach that enables you to evaluate programs in a repeatable, consistent, and credible way. The Impact Measurement Framework® described in this book presents such a model, which will help you with the evaluation of individual programs. That said, we will use the term “measurement” throughout this book to discuss the processes and measures that capture actionable, specific, and credible information.

6. The LMS Is a Foundation for Measurement

Learning management systems play a very important role in a measurement program.

Consider the vast and important actionable information in your LMS. The LMS has all the source data for learners themselves, their roles, languages, locations, and managers; employee enrollments, completions, times in courses, certifications, and scores; course descriptions by category, type, vendor, and modality; and many other important dimensions such as competencies, career plans, and even performance ratings. These elements are the actionable “dimensions” in your learning measurement program.

In addition, almost all LMS systems have an online assessment tool that can be used for end-of-course surveys. These tools always have the most basic question types you need for end-of-course surveys. Most also have built-in analytics tools, which could be used to analyze and format information for a variety of audiences.

Most organizations are not tremendously satisfied with their learning management systems. In fact, our 2007 research found that 24 percent of LMS owners are considering or planning on switching LMS systems. Despite the challenges of selecting and implementing these systems, it is important to realize that one of the biggest business benefits of an LMS is its ability to capture, analyze, and deliver information. In fact, when we ask organizations that have had an LMS for two years or more to describe the biggest benefits they have seen, measurement and data are ranked number one.

For those companies without an LMS, this should not stop the measurement process. Many organizations scan or type end-of-course surveys into spreadsheet applications and other tools, to gain the value of a consistent and repeatable measurement process.

Need for Data Standards in the LMS

Since the LMS is considered the “single source of truth” for assessments, completions, and other information, you will find it critically important to create data standards. For example, comparing several courses with inconsistent names against each other may prove difficult or impossible (for instance, which of the two hundred courses in “safety” should be compared against each other?). With e-learning, if some courses have Aviation Industry CBT Committee (AICC) and Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) tracking and others do not, it will not be possible to compare completion rates or other volumes across courses. Once the elements to measure have been determined, establish some data standards, so that all the data collected in the LMS is consistent and complete.

Standards should specify how courses are named, how they are grouped, what assessments are used for e-learning courses versus ILT versus self-study, and how learners are grouped. Without such standards, analysis of the large volumes of LMS data you will receive is difficult. This book will help managers understand the types of standards that are necessary.

7. Dedicate Resources

In our High-Impact Learning Organization research,4 eleven different organizational elements of corporate training were reviewed to identify what structure, initiatives, and programs drive the highest levels of effectiveness or efficiency. One organizational decision that has a major impact on results is the creation of a dedicated measurement team (or person). Organizations with some dedicated measurement resource are 11 percent more effective and 9 percent more efficient than those without.

Why is this? Simply because the measurement of training is complex and takes focus. Additionally, since we highly recommend that your measurement program be consistent across all programs, someone must develop it, steward it, train others in the steps you use, and run reports and analyses. This person or group can also evaluate the many models and techniques for data capture and evaluation, and they can develop and refine the ongoing measurement process.

Large, well-run training organizations typically have a measurement person or group: At Sprint University, an organization with more than three hundred employees, there are several people responsible for measurement. At AT&T Wireless, with a national training organization of more than 150 people, three training staff members are dedicated to measurement. United Airlines has two dedicated measurement staff members. The IRS has an entire evaluation and measurement team dedicated to measurement.

Even if you are a small organization, at a minimum, there should be an employee who “owns” the measurement process on behalf of the entire organization. This employee develops the process, trains program managers in its implementation, works with the technology team to implement tools, and analyzes program results and other data. In general, the total measurement effort should only cost 2 to 4 percent of the total training budget.

8. Start Simply and Evolve Over Time

The final principal to remember is that training measurement takes patience. There are so many possible things to measure. Our research reveals that organizations with successful measurement programs start simply and grow over time. Initially, training volumes, standard Level 1 satisfaction surveys, and standard measures of client satisfaction may be a good start. Developing these measures into a consistent and repeatable process is a huge achievement.

Over time, you should create a set of standard end-of-course surveys and implement a process to measure alignment. Start measuring costs and metrics against your plan, and implement a standard process for business impact. Every organization we studied grows its sophistication and maturity over a period of years. Rather than trying to measure everything from the beginning, establish a simple but process-based approach, and then gradually add more information and target greater audiences over time.

Notes

1. An operational business plan for learning is typically built to support the general business plans for products, revenue, services, and other primary business functions. As a support unit, the training plan should establish annual goals and objectives that support each strategic goal or initiative. Typically, these plans include strategy, budget, program plans, organizational model, operational measures (number of courses, enrollment objectives, etc.), alignment with HR-talent management initiatives, major capital investments (i.e., a new LMS), and major commitments by quarter. Such a business plan should be widely circulated and signed off by all major business units. It “commits” the L & D function to deliver against this plan and forms the basis for operational measures.

2. For more information, see The Corporate Learning Factbook: Benchmarks for Learning Organizations. Bersin & Associates/ Karen O’Leonard, May 2006. Available at www.bersin.com.

3. For more information, see The High-Impact Learning Organization: WhatWorks® in The Management, Organization, and Governance of Corporate Training. Bersin & Associates, June 2005. Available at www.bersin.com.

4. Ibid.