Chapter Two

The Pros and Cons of Using ROI

Much has been written about the importance of measuring the ROI (return on investment) of training programs. ROI is frequently positioned as the “ultimate measure” of training effectiveness. In fact ASTD1 “ranks” organizations on their effectiveness by whether or not they use ROI measures. While ROI has its benefits, we are not big fans of focusing on this approach. This chapter discusses the pros and cons of using ROI.

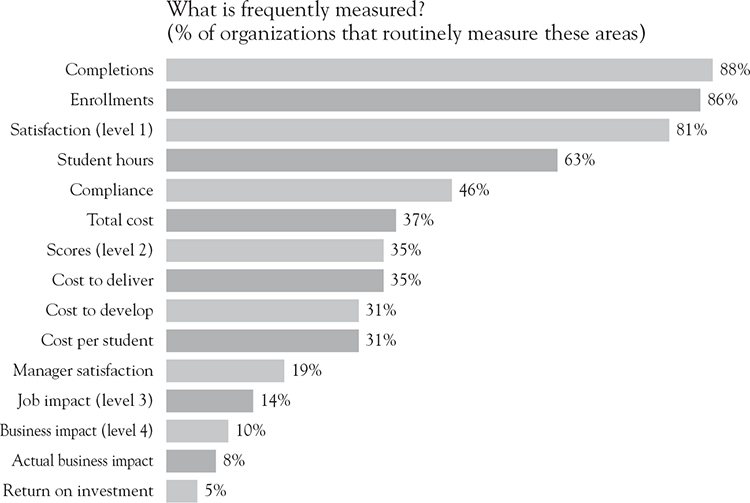

First, it is important to realize that ROI measurements are not used as frequently as one may think. When we interviewed High-Impact Learning Organizations,2 we consistently heard resistance to using ROI as a core focus of their measurement programs. Rather, these organizations focus much more heavily on operational measures and use ROI occasionally for a few very special projects. This research showed that only 10 percent of organizations even attempt to measure business impact and fewer than 5 percent regularly measure ROI.3 Figure 2.1 shows routinely tracked information.

Why this low level of usage? Our research found that measurement of ROI is time-consuming, often inaccurate, usually not very actionable, and rarely credible. While the concepts of ROI are important and can be used for specific high-value projects as part of the performance consulting process, I believe you should use ROI sparingly. At the end of this chapter I will explain some very high-value, easy ways to use the ROI concepts.

Let me now discuss a number of pros and cons of using ROI.

Figure 2.1 Information Routinely Tracked

ROI Analysis Assumes That Training Is Treated as an Investment

First, let us discuss the basic principles of ROI measurement. ROI analysis is not something new. The concepts have been around for years and were designed (as taught in business schools) to measure the financial return over time from a fixed capital investment, such as a machine or building. The word “return” refers to some financial income that is captured over a period of years, and the term “investment” refers to a capital investment (not an expense). ROI analysis was designed to help a company prioritize capital investments and solve the problem of asset allocation. It has very specific meaning to a business or finance person.

It was designed to answer questions such as:

• Should we invest in Machine A to improve productivity or continue to do things manually?

• Is Machine A (a very expensive machine) a better investment than Machine B (a less expensive, but perhaps less robust model)?

• Should we spend money on a new manufacturing process or on hiring more salespeople? Which is a better long-term investment?

• Should we buy a new company or build out a product ourselves?

Suppose a profitable company makes $100 million of profit each year. One of the big decisions to make is where to invest the $100 million to optimize the company’s growth and profitability. To answer this question, companies look at a list of possible investments and rank them based on their ROI.

ROI analysis also has the concept of a “hurdle rate.” The “hurdle rate” is a company’s existing cost of obtaining new capital (the cost of issuing debt or raising money in the public markets). To a financial analyst, a winning investment must generate a return (ROI) that is greater than the company’s existing return on other investments (the company’s so-called “hurdle rate”). For example, if the company is currently generating a 15 percent return on assets, it would clearly be a mistake to invest in a new project that generates a 5 percent return on assets (unless the company felt this investment was necessary to offset some other risk).

The key to ROI analysis (from a financial perspective), then, is that:

• Investments are made over a period of time, so the return may take many years to realize (and the investment itself may take place over a period of years);

• Investments should be compared against each other to help prioritize them;

• Investments should always generate a return that is greater than some established “minimum”; and

• ROI analysis should be done before the investment is made so that the exercise helps decide whether or not to invest.

Now, let us consider whether training programs fit into this model. Is the training budget considered an investment that delivers return over time? Are you willing to compare the ROI of training programs with the ROI of other investments in the company? Do you have a “minimum ROI” for which you are ready to compare your programs? Typically, the answer to all these questions is no.

Unfortunately, in almost every company I talk with, training costs are considered an expense (similar to all of HR and IT). The funds spent on training are charged against income in the current year, so there is no way to “allocate” this expense to a multiyear payoff. And even though we all know that training generates returns over many years, in most companies it is necessary to re-justify or re-budget training dollars each year.

Let me cite an example. One of our research clients (an electric utility) performed an extensive ROI analysis of an operational training program. He computed an ROI of over 2,000 percent (more than a 20 times return per dollar invested). He then made the mistake of presenting this finding to one of the finance executives in the company.

This executive looked at the result and became quite agitated. He said to the training manager, “Do you know the return on investment we generate across the entire business of generating electricity? It is around 5.5 percent. What your analysis is telling us is that we should shut down our power plants and get out of the business of generating electricity and focus exclusively on training. Am I to believe this?”

This is why we discourage organizations from an over-focus on computing the ROI of training—it is not the correct financial model. The simple version of ROI taught by Jack Phillips (benefits – costs)/(costs) is really a computation of potential cost recovery, and should probably be called something else. When you throw around the term “ROI,” business people hear the words “return” and “investment” and think very different things than what you are truly computing.

So how should you analyze your financial impact on the company? Going back to the issue of training being a support function, remember and accept the fact that training is a cost center. Your job in managing a cost center is to develop a well-aligned operational budget that conforms to corporate guidelines and benchmarks. 4 You should compare yourself to others in your industry and make sure you are spending the right amount of money in the right places. Of course you should try to measure the business impact of your programs, but do not build analyses that assume that training itself is generating revenue or profit. If every support function in the company did this type of analysis, we would see the “ROI” of IT, the “ROI” of management, the “ROI” of buildings and grounds, the “ROI” of the security guards, the “ROI” of the phone system, and on and on. When you added these all up, you would see that every dollar of revenue is probably being captured 20 to 30X by these different support groups.

How do you justify your expenses and ask for more money? Remember that any expense dollars allocated to training are coming out of some other expense budget in the company (they do not come out of incremental revenue). Your goal in managing this budget is not to compare and optimize this spending against other long-term investments (such as plant and equipment); but rather to prioritize these programs within the budget and make sure the company is receiving the highest possible impact at the lowest cost from each. You should justify your investments through benchmarking and industry-wide comparisons. You should try not to use it as a way to “cost-justify” or “grow” your budget.

There are excellent ways to use the ROI concept, and these are discussed later in this chapter.

In-Depth ROI Measurements Are Often Difficult to Believe

One of the risks of using ROI analysis is that you may run into someone who attended business school who rigorously questions your analysis. As the electric utility example describes, exposing ROI measurements may put you at the risk of losing credibility. Consider the following challenges that are likely to trip you up:

1. Can You Really Compute the True Cost of Training?

The only way ROI makes sense is if you know what the “I” is—the total cost. The total cost of training is much more than the cost of development. It is the cost of:

• Development and all the “burden” of development tools and systems;

• Materials and consumables used in delivery;

• Instructor preparation and delivery time, burdened with the instructor’s salary, benefits, and other costs;

• Delivery expenses through technology, such as the “burdened” cost of your LMS, amortized over years;

• Students’ salaries for the time spent in training and travel expenses; and

• The opportunity cost5 of the students’ attendance (the lost opportunity of these people not doing their real jobs during the time of training).

If you glibly leave some of these out, a financial analyst may want you to go back and compute them all. Very few training organizations have a cost-analysis system set up to capture these costs.

2. Can You Isolate the Effects and Compute Their Return?

Of course this is the biggest challenge. Time and energy must be expended to identify a quantifiable measure that can be considered a real financial return (for example, a sales increase). Even after computing such a measure (and making all the assumptions necessary), it is very hard to correlate this directly to training. If you believe you increased sales, the VP of sales may argue that in fact the sales increase was for another reason (e.g., the fantastic performance of his team, the attractiveness of a new product, marketing programs, etc.).

3. If You Compute ROI, Can You Determine Whether a Computed ROI Is Appropriately High?

Suppose you do compute an ROI. How do you determine whether the ROI is high enough? Is 100 percent ROI good or bad? What are you comparing it against? Suppose the vice president of sales noticed that the training department got an ROI of 200 percent on a certain program that cost $ 500,000 to develop and deliver. And suppose that “return” is an increase in sales revenue. Seeing this return might cause the vice president of sales to claim that a much higher return would have been achieved by hiring two additional sales representatives, with each representative generating five to ten times his or her salary in sales, for a 500 to 1,000 percent “return.”

Your ROI number may feel good but, when compared with the many possible investments throughout the company, it may fall far short. Are you prepared to compare your ROI on training against other true investments in the company? Can you be sure that the ROI you compute, if it is believable, is really the best use of the company’s funds?

In Concept, the ROI of Training Should Be Extraordinarily High

This takes us to the next point. What is a reasonable ROI for training? When I read examples of companies that generate a 67 percent ROI or 125 percent ROI, I wonder: Should we even consider these as “high” or “low”?

Conceptually I believe well-developed training creates a very high ROI—ten to one hundred times the investment (hence thousands of percent ROI). It should be, since training is one of the most far-reaching and highly leveraged expenditures in your organization. Let me explain why.

Consider the following numbers: Training investments are typically only 2 to 3 percent of payroll; yet, they improve the productivity and effectiveness of that other 97 percent to 98 percent of payroll spending. If these investments are not generating ten to one hundred times their return, then I would question whether this money could not be better spent elsewhere. Although measurement of this return is difficult, the whole premise of training is that it is a highly leveraged resource across many employees who are consuming and spending many, many dollars. Executives who understand the value of employee development know this, so they invest year after year—even without scientific ROI analysis.

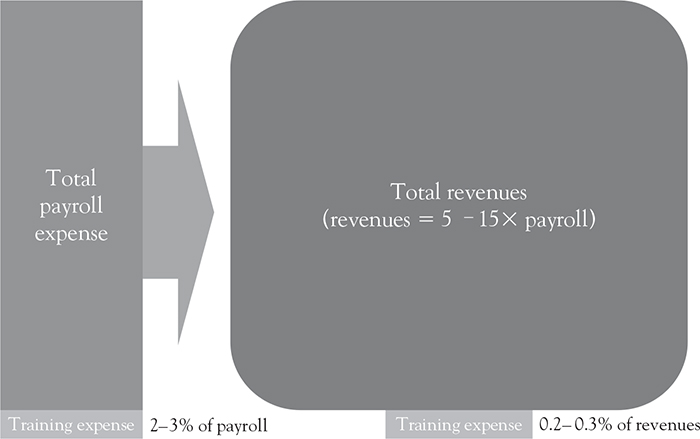

Consider the sample numbers illustrated in Figure 2.2: The Financial Leverage of Training. Training typically consumes 2 to 3 percent of payroll, and most companies’ revenues are five to fifteen times their payrolls. This means that training expenditures as a percent of total sales are very small (from two-tenths of a percent to half a percent).

This small expenditure is designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of this tremendously large number—the revenue and profitability of the entire company. If a training program increases sales by a few percentage points, for example, the leverage is huge. Suppose, for example, that half of the entire training budget was allocated to sales training. If this budget (which would correspond to, say, two-tenths of a percent of sales) increased sales by only 1 percent, the ROI of this expenditure would be 500 percent. We believe this is a highly conservative assumption. Therefore, any training program that does not truly generate 500 to 1,000 percent ROI (measured on sales) is falling short of its potential!

Figure 2.2 The Financial Leverage of Training

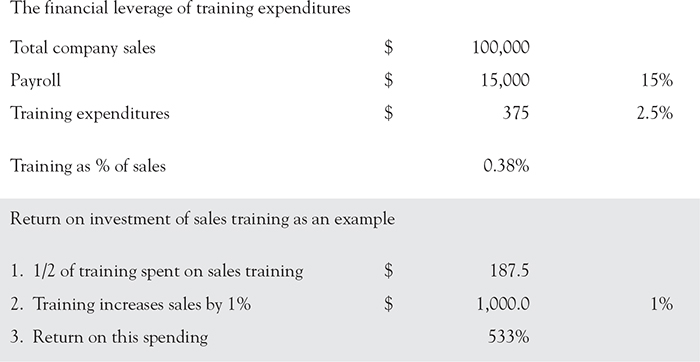

Figure 2.3 shows such numbers for a company with $ 100,000 in sales.

As this simple and conservative example shows, a very small investment in sales training (in this case, half of the entire training budget) can have a huge impact on revenue or profitability. The argument here is not that training does not generate an ROI but, rather, that the ROI, although difficult to measure, should be very high—far higher than most organizations can compute through ROI projects.

Figure 2.3 Conservative ROI in Training

It Is Very Difficult to Correlate Outcomes Specifically to Training

We all know this. While many books and techniques can be used to try to correlate outcomes to training, in almost every case I have seen these correlations are easy to argue with. Here is an example.

When I was involved in the development of e-learning programs for Circuit City, it was decided to try to measure the ROI of a particular program—an e-learning program focused on training store salespeople to sell extended warranties (a highly profitable product). The training was deployed to a select number of stores. Then sales of extended warranties in those stores were measured and compared to the sales of the same product line at stores that had not participated in the training. The test period lasted approximately sixty days (that is, sales results were examined for sixty days following the training program).

The results were analyzed by salesperson. A chart was developed that compared sales of extended warranties for the salespeople who took the training to the sales of those who did not. The results showed that those who took the training sold approximately 3 percent more in revenue than those who did not. This seemed good enough; then this result was multiplied by the total number of stores operated by Circuit City. The determination was made that this particular program would generate millions of dollars in revenue and profit for the company.

However, the impact of other factors was ignored. At the request of Circuit City, a statistician was hired to further analyze the data. The statistician looked at many variables, including the age of the salespeople, their length of employment with the company, their job levels and other demographics. The statistician found that, while the “average” of the trained sample did sell more products, the cause of this sales improvement was not the training. By correlating many factors into the sales improvement, the statistician, in fact, determined that the training itself was only responsible for less than half a percent of the improvement in sales.

The factor that had the highest correlation (or greatest cause) for sales improvement was “time with the company.” It turned out that salespeople with more experience with Circuit City were selling 200 to 300 percent more extended warranties than new salespeople. Since the sample of trained sales representatives just happened to be slightly biased toward experienced employees (a complete accident), the “trained population” had just enough increased seniority to show a 3 percent higher increase in sales.

So we have to assume that “isolating the effects of training” are difficult and often suspect. Before you embark on a serious ROI project, think about the “ROI of ROI analysis”—Will the project itself generate enough return to justify the time and energy to capture the data? Can you easily and credibly compute the “return”?

(Despite these challenges, there definitely are ways to directly capture business impact data from training. I discuss several ways of directly correlating training to business impact in Chapter 6: Measurement of Business Impact.)

How Do You Make ROI Actionable?

The final challenge with the use of ROI is that ROI analysis, when conducted as a project to evaluate a single program, is rarely actionable. Measuring the ROI of a single training program does not tell you how well it may compare against others in your portfolio. It rarely tells you which elements had the most or least impact. And it does not usually bear up to comparison against other investments in the company.

On the other hand, some companies have found ways to use the ROI concept to make it more actionable—by essentially computing “potential ROI” before developing a program. Let us now discuss this approach.

Use of “Potential ROI” During Performance Consulting

So where does ROI fit? One of the most valuable uses of ROI is to use the concept during the needs analysis or performance consulting phase. In other words, compute ROI before you even start developing a program.

How do you do this? Keep it simple. Using the signoff form from your business manager (we will discuss this in detail later) and your internal performance consulting process, identify the size of the problem to be solved (in dollars), the potential savings you believe you can achieve (being reasonable), and the planned program budget. You can then compute a “prospective ROI” easily. The key here is to be very reasonable about the potential performance improvements and to gain buy-in from the business owners in developing this number.

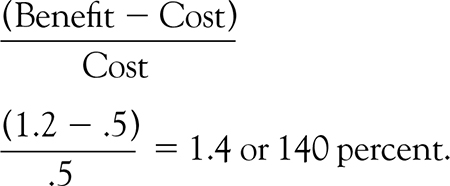

For example, suppose your vice president of sales asks you to develop a sales and technical training program for a new product line. You determine that the total sales goal for this product for the next year is $ 30 million. Working with your VP of sales, you agree that this sales program is likely to have a 3 to 5 percent impact on sales productivity overall. The program, then, has a potential benefit of 4 percent of $ 30 million, or $ 1.2 million. If the program costs $ 500,000 to build, the potential ROI is:

Now this number may or may not seem high relative to other investments in the company, but when used at this phase you see two things: first, it is positive, illustrating that it may in fact be worth spending $ 500,000 on this particular program. Second, you can now look at the 140 percent potential ROI and compare it with other possible programs and investments. For example:

Are there other sales enablement programs that may generate a higher ROI? What if we spent less on this product rollout and spent more on the overall sales training career curriculum?

Is 140 percent too low when compared to all the other programs you are building? Perhaps the $ 500,000 budget is too high and we need to find a way to increase the “potential ROI” up to 300 percent or more by cutting the cost and possible benefit? (Notice that the biggest increases in ROI come when costs of the program are cut, not when benefits are increased.)

Generally such “potential ROI” analysis is very valuable at this phase, because it aids in the needs analysis process as well. Consider the other benefits of regularly using this simple process:

• It forces the program manager to clearly investigate the root causes of a problem and how these can be solved.

• It illustrates the potential benefits to the business managers who are sponsoring the training program.

• It helps the organization decide what level of investment is appropriate for this particular program.

• It helps the organization prioritize this particular program against other programs.

Both HP and Caterpillar use this simple process. An excellent way to implement this is by adding such calculations into the “signoff form,” forcing both the line of business manager and the training program manager to work together to both compute the potential benefits and scope the potential budget.

If you institute this process, you will naturally want to compute the “actual ROI” at the end of the program. Here my suggestion is to keep it very simple or use approaches like the “Success Case Method,” developed by Dr. Robert Brinkerhoff. Brinkerhoff’s five-step approach uses examples and case studies to identify actionable information about the real benefits of a given program.6

“Performance-Driven” Versus “Talent-Driven” Training

The use of ROI is not going to go away. Despite its many limitations, it is a conceptually simple approach to understanding how different programs compare in their value. Ultimately, however, in order to use ROI concepts well you have to consider one important factor: the nature of the problem you are solving.

Let me digress here and discuss an important point. Broadly speaking, training programs fall into two categories: performance-driven programs and talent-driven programs.

Performance-driven programs are those programs designed to solve specific performance problems. For example, if you determine that managers in your company are inadvertently creating sexual harassment claims, you would purchase or build a one-or-two-hour sexual harassment training program. This program would be designed to solve this problem. Similarly, if you find that your call center representatives are entering the wrong information into your online service system in certain fields, you would develop a one-or-two-hour program designed to teach them how to use the system correctly and avoid these problems.

Many of your training programs are designed for these types of problems. These programs are typically fairly easy to build, fairly easy to deliver, and it is relatively easy to compute a potential ROI (you measure the change in the actual performance problem). (See Figure 2.4.)

Figure 2.4 Performance-Driven Versus Talent-Driven Learning Programs

The second type of learning program we build are what I call “talent-driven” learning programs. These programs develop rich and complex skills and deliver in-depth levels of information that solve many problems. In fact, they “develop people” rather than “train people.” In the example of sexual harassment, you may find that, in fact, managers not only have problems in this area, but they also have problems in coaching employees, evaluating employees, communicating, conducting meetings, and goal setting. In fact, you may find that what you need is an entire management curriculum (leadership development or management training program) to address these problems.

This second approach would involve development of a much longer, richer development program that may include instructor-led training, online training, special assignments, assessments, and more. The cost of developing and delivering this rich, longer-term program are likely to be 10X the cost of building the performance-driven learning solution. And the rollout time and complexity will be much higher. Such programs include onboarding, leadership development, and other forms of long-term career development.

How do you measure the benefits of such talent-driven programs?

For talent-driven learning programs, computing ROI will rarely be meaningful. These programs are designed to solve many problems and generate many benefits. They typically have broad and large benefits such as.

• Improvements in employee engagement and satisfaction

• Improvements in retention

• Improvements in the ability to hire

• Improvements in work quality

• Improvements in cycle time through increased communication and teamwork

As I discussed earlier, these benefits will generate very high ROI, but are difficult or impossible to measure. So what should you do?

Rather than embark on a long-term one-or-two-year ROI analysis, we suggest you take a different approach. In our research and discussion with clients, we found that the programs with the highest ROI are the programs that are best aligned with the most urgent and important problems of the business. Alignment is one of the most important measures we discuss in this book (see Chapter 7: Measurement of Alignment). If you align the program well, developing a strong agreement on its value, goals, and target audience, the impact will be large. You can then use the other techniques in this book, along with the Success Case Method by Dr. Brinkerhoff, to identify specific examples of how this program is driving value.

Going back to the Circuit City example cited earlier, we found that after all the ROI analysis was complete and many years of e-learning had been delivered, one of the biggest impacts from product and sales process training was developing confidence in the retail sales force. This confidence led to retention, engagement, and a commitment to work hard and contribute to the company. In a large organization like Circuit City, a 1 percent increase in retention is worth tens of millions of dollars per year. While it took us many years to realize and gain perspective on this return, ultimately it showed us that these talent-driven training programs were of high value and freed us to work on capturing more specific, actionable information.

Don’t Let ROI Become “Return on Insecurity”

One of the traps training managers fall into is using ROI to cost-justify a large or questionable program. A training director in our research made the comment that he considers ROI to be “return on insecurity.” His premise is that ROI analysis is an attempt by training managers to try to justify their existence. His argument is that, when training programs and processes are well aligned with urgent business needs and a well-defined performance consulting process is in place, the training professional will never be asked to compute ROI.

I have generally found this to be true. Spending your time building a solid performance consulting and business alignment process is far more valuable than implementing ROI projects on existing programs.

We recently discussed the topic of training measurement with the CLO at Saks Fifth Avenue. Saks has a very well-developed enterprise learning program, which includes in-depth training for managers, buyers, and retail salespeople. They have an advanced e-learning solution built on a proprietary platform, which delivers training to every Saks store in the country. Saks’ “Business of Buying” program is considered one of the most strategic investments the company has made.

When we asked the CLO whether she was asked to measure the return on all these investments, she told us “never.” Their programs are so well aligned with the needs of the business that no one at Saks has questioned the value of this ongoing investment in learning.

Notes

1. ASTD: American Society of Training and Development, the U.S. industry trade association for corporate training.

2. For more information, The High-Impact Learning Organization: WhatWorks® in The Management, Organization, and Governance of Corporate Training, Bersin & Associates, June 2005. Available at www.bersin.com.

3. This survey data was captured during the summer of 2006 from 136 large organizations (demographics are available in Appendix III). Interestingly, this survey was also conducted in 2004 and the results of the two surveys are almost identical.

4. For more information, see The Corporate Learning Factbook® 2007: Statistics, Benchmarks and Analysis of the U.S. Corporate Training Market, Bersin & Associates/Karen O’ Leonard, February 2007. Available at www.bersin.com.

5. “Opportunity cost” is defined as the actual “lost opportunity” from students attending training instead of doing their regular jobs. It is usually computed by totaling up the employees’ salaries—but in reality the costs are higher. They include the cost of travel, time away from work, and the loss of productivity (sales, production, and so on) that is not taking place during training.

6. Dr. Robert Brinkerhoff. The Success Case Method: Find Out What Is Working and What Is Not. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2003.