Chapter Four

The Impact Measurement Framework®

Now let us move into solutions.

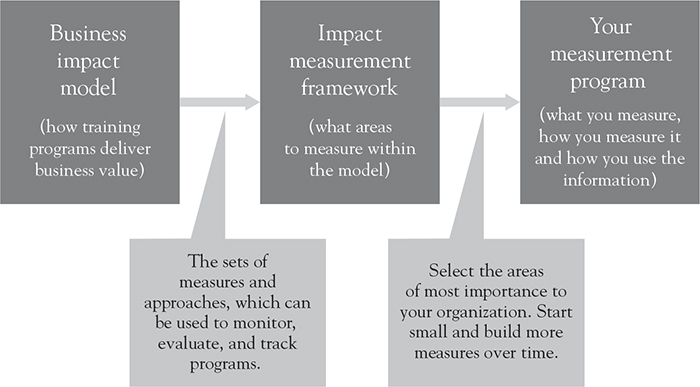

After dozens of interviews with learning and development managers and a review of many different approaches to measurement, I cataloged hundreds of measures and techniques. Many of these were widely “outside” of the Kirkpatrick model. To make these findings easy to understand and use, we developed a more modern and complete model for training measurement we call the Impact Measurement Framework®.

The goal of this framework is to give training managers and executives a complete and updated model from which to build their measurement programs. It is not a recipe, but rather a series of well-researched measures and approaches you can immediately use. No organization will adopt the entire framework in year 1, but over time you will see that each element of the framework adds new actionable information.

Let me also describe how this framework was developed. Rather than just collecting various measures to capture, we spent some time thinking about the entire end-to-end process that training organizations use to add business value. In other words, we tried to build a “causal model.” Just as in the sales measurement example described in Chapter 1 (where “leads” lead to “opportunities” and “opportunities” create “sales”), we need a causal model in training from which to derive relevant measures. If we believe in this causal model, then we can select the measures at each stage to understand how and why a program is or is not working. The result: highly actionable information.

I named this end-to-end process the Business Impact Model®, and the Measurement Framework® derives from this model. You should be able to apply the framework to any step in the process you want to understand. Because the framework matches the Impact Model at each step, you can use the two together to build a “cookbook” for developing a measurement program.

What value is the framework? First, I hope it will educate you and help you understand each of the elements of training that drives value. Second, it will give you many easy-to-implement ideas for measures and approaches that can be implemented quickly. Finally, as you embark on your measurement journey, the framework (Figure 4.1) can serve as a roadmap to help you advance and improve your measurement program over time.

Let us now begin with the Impact Model®.

Figure 4.1 Using the Impact Measurement Framework

The Business Impact Model®

As I talked with many companies about their challenges in measuring training, I realized that, in order to measure their effectiveness and efficiency, one had to make many assumptions about how training programs actually work. If you want to measure the soundness of your car, for example, you have to understand that oil temperature and water level are important indicators of engine health. In the same way, if we want to operationalize the measurement of training, we need to know what elements of training really matter—which elements drive impact.

The model is titled “Business Impact” for a reason: it attempts to decompose all the elements of a training program that drive business impact. Remember that, unlike traditional education, in corporate training every single outcome is a means to an end: improving business performance.

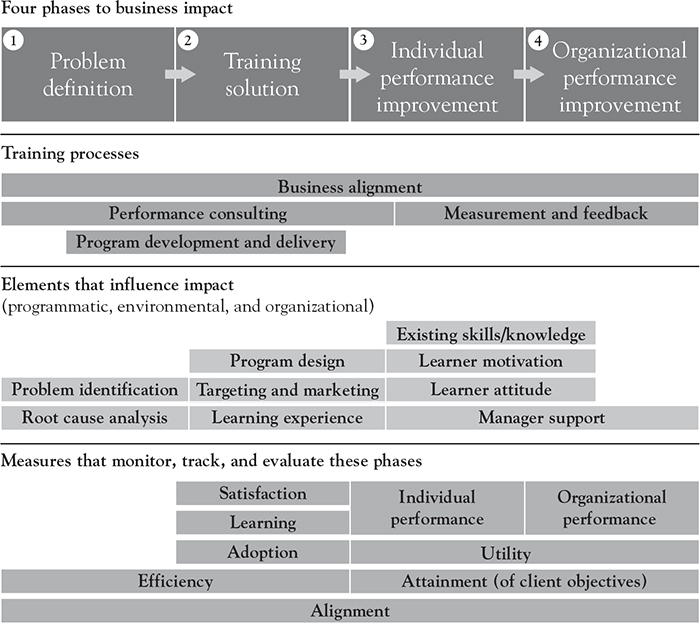

As shown in Figure 4.2: The Business Impact Model, there are three major parts of this model:

Figure 4.2 The Business Impact Model

The four phases of a training solution (depicted horizontally at the top);

The specific training processes that support each of the four phases (shown in the middle); and

The program, environmental, and organizational elements that thereby influence business impact (depicted at the bottom).

The model is designed to be simple, easy to understand, and consistent across the four phases. This is how it works.

How the Business Impact Model Works

Each business impact phase is supported by a training process (that is, something the training department does), and a set of processes and environmental issues, which drive results. If you agree that this model makes sense, you can measure one of the processes or elements to capture actionable information about your training programs.

Let us step through the four training phases:

1. Problem-Definition Phase. The first phase of a training solution is the most important—the challenge of clearly defining the problem to be solved. As any training manager knows, often the problem presented is very vague: “We are not selling enough product A so we need some training” or “Our manufacturing process is creating errors and we need training to improve quality” or “Our new employees need onboarding.”

This process includes identifying, quantifying, and defining the business problem, making sure that this problem is aligned or well-prioritized by the business, and understanding its causes.

The first process in problem definition is a critically important phase I call “business alignment.” In this phase you work with the business managers and your executive team to make sure you have prioritized, diagnosed, and scoped the problem to be solved. In this critical phase you understand that a problem exists, you interact with the line manager to scope its size and priority, and you gather requirements about the type of solution the line manager desires. (One of the critical ways to measure business alignment is through a manager check-off form, which we discuss in Chapter 5: Implementation: The Seven-Step Training Measurement Process.)

The second process in problem definition is “performance consulting” (also called “needs analysis”). Performance consulting (a well-documented process) is the process of unraveling the business problem to its root causes, identifying the learning components of these causes, and developing a set of learning and informational plans to solve the problem. The output of performance consulting is a very clear set of learning requirements and a clear understanding of how the root cause of the problem will be solved through this learning.

Let us use an example to explain these two critical processes. Imagine that your company suffers from lackluster sales of a new product. First, the training manager must make sure this is a well-recognized problem that the vice president of sales feels warrants the time, money, and effort to solve through training (business alignment). During this step, the training manager should quantify the amount of sales the vice president feels is being “lost.” They should gain approval to consider training as a solution and make sure that the managers are willing to let salespeople spend the time in training to solve the problem. Sign-off forms and interviews are a good tool to use here.

The second step (performance consulting) is to now research, study, and understand the root cause of this problem which, in turn, will lead to a set of learning objectives. For example, through a series of interviews and field meetings, the training manager may find that one root cause of low sales of the new products is the sales representatives’ inability to understand and explain the value of the features under certain well-known customer objections. This is clearly a learning problem that can be addressed by a training solution. This phase is one of the most important steps in design and measurement.

The measurement of these two processes, business alignment and performance consulting, is very important. If you aren’t solving the right problems, it doesn’t matter how well the programs work. One of the CLOs we interviewed told me that her single most important measure was asking her training directors to give her the prioritized list of the business problems they were addressing in their respective business areas. She then matches this list against the list of business priorities she receives from the business managers themselves. This gives her a powerful “dashboard” for alignment.

2. Training Solution Phase. The second phase in training is development of the training solution itself (where you probably spend much of your time). This phase includes the process of designing, building, targeting, launching, and delivering the training program itself. Using the information obtained through the business alignment and performance consulting process, the training organization now builds the appropriate training program and schedules and performs its delivery. The business impact from this phase is influenced by three key elements.

A. Program Design. Most training managers believe that this is where the core value resides. While design is clearly a critical element, other elements can also make or break a program. Factors that influence design include:1

• The learning objectives;

• Specific skills to be imparted;

• Audience characteristics, such as size of audience, language, existing skills, age, time to learn, experience, seniority with the organization, access and familiarity with technology, and many more;

• Budget for the program itself;

• Location and availability of technology;

• Skills available in the learning organization;

• Time available to build the program and time available for delivery;

• Other programs that complement, supplement, or compete with this program.

B. Targeting and Marketing. In addition to program design, the second area in the development and deployment phase is the process of targeting and marketing:

• How well was the right audience defined and targeted?

• Do we have the right people in attendance or taking the course?

• How clear are the objectives to learners and their managers?

• How well were the learning objectives matched to the audience? Did we clearly understand the background of these people? Was the course made relevant to their needs and work environment?

• How well could the learners identify the right program? Was it clear to them that this was the course to take?

Although these issues seem less important, they can become critical if not handled well. Many of these issues revolve around the role of first-line managers:

• Do managers know the right people to enroll in the course?

• Do these managers support the course’s value and the time commitment required?

• Do managers understand the schedule, pre-requisite, and time requirements of the program?

C. Delivered Learning Experience. And the third issue in program design and delivery is the delivered learning experience. Here there are many factors involved:

• How effective was the instructor at delivering the material?

• How well did the technology work?

• How comfortable was the learning environment?

• Did the experience itself help or hurt the learning and business outcome?

The learning experience is dependent on many things: instructor capabilities, quality of materials, quality of e-learning experience, seamless delivery of technology, effective use of audio/video and simulations, quality of collaborative experience, ability to interact with instructors and subject-matter experts, pace, and so on. Learning experience is a very popular area to measure because it often best reflects the learners’ direct satisfaction. Such satisfaction may not be quantifiable or scientific, but it is always relevant to the business effectiveness of a program.

We know, for example, that training programs that are “fun” and “memorable” do leave a long-lasting impact. On the other hand, for some programs (for example, leadership training) the instructor’s personality, focus, and experience are more important.

In an e-learning program, the learning experience includes such things as speed and ease of use, quality of graphics, sound, and video, and ease of interactivity through the mouse or other input devices. These delivery issues vary widely from event to event.

3. Individual Performance Improvement Phase. The third phase of business impact is what happens to the learners after they go back to their jobs. How well did the individual learner grasp and apply the material to improve his or her performance? How well did the learning actually apply? What tools or job aids did they bring back that they can apply? How does the program itself support the learners over time, as they continue to improve their performance?

Ultimately, performance improvement is our goal—but rarely do training managers consider how to make this “transfer” phase successful. Ultimately, if you want to measure this phase of the program, we believe there are four environmental and organizational issues:

A. Existing Skills and Knowledge. What was the existing level of knowledge in the learner? Specifically here we should ask questions such as:

• What level of background did the learners already have, and was the program too introductory or too advanced?

• How well did the learners already understand the material to be presented and was the program consistent with their existing knowledge?

• Where did the program fit into their already existing level of experience in this area?

If a learner’s existing skills and experience are in conflict with the program, no amount of design or learning experience will drive impact. Typical ways to measure existing skills and knowledge are through pre-program assessments. Most advanced e-learning systems (LMS and LCMS systems) and courseware also allows the program to skip introductory material based on this pre-assessment.

Notice that this topic is not considered a “satisfaction” or “learning” issue, because it really relates to how well the program drives performance improvement. If the program is not correctly positioned based on the learner’s existing knowledge, the learner’s performance improvement will be small.

B. Learner Motivation. Learner motivation, the second performance improvement factor, is one of the most important influences on impact.

• Does the learner care about the program? Has it been positioned in a way that makes the learner want to learn?

• How motivated is he or she to learn? Was he or she given the right level of support, compensation, time, and management approval to take the program?

• If the program is mandatory, does the learner really care about the program, or is he or she just taking it to receive a completion certificate?

• Are the learners in this program the type of employees who want to learn and improve?

• How well did the manager give incentives and coach the learners to attend and receive value from the program?

Many factors influence motivation, and it should always be considered as part of the design and knowledge transfer process. One of our clients, Yum! Brands, embarked on an organization-wide learner survey to ask their employees how well prepared and motivated they were for available training programs. This research provided the organization very valuable information on the need to further inform and motivate managers to prepare employees for training.

C. Learner Attitude. Learner attitude is directly related to motivation.

Attitude, of course, is a highly subjective measure. The issue here is “readiness to learn.” Did the learners come to the course with an open mind? Did they have enough time to leave their work environments and actually engage in the training process? How can training managers make sure that learners really want to learn this material and stay engaged during the learning process? Typically, attitude is driven through program design, alignment with line managers, and a design that appeals to the particular learners to be addressed. Simple questions such as, “How well did this course engage you in the learning material” and “How receptive were your employees to this course (asked of managers)” can gauge attitude.

D. Manager Support. How well does the manager support this program?

Much of our research continues to show that first-line managers can make or break an employee’s development experience. Our High Impact Talent Management® research2 found that the single management process that drives highest business impact is coaching: how managers coach and support their employees. A key part of such coaching is to help employees to understand how to build and execute their own development plans.

Such support directly impacts training results. If managers do not understand and support the information and skills being taught, the learners may find that the course was “interesting” (that is, satisfying), but difficult to apply on the job. The manager may even feel resentful that the individuals were away from work.

An excellent example of the power of manager alignment is a learning program we evaluated for a large consulting firm in Canada. This firm had been sending its consultants to a rigorous project management certification program that received very high marks in satisfaction and learning (Levels 1 and 2). The CLO felt proud of the program and its results and frequently promoted it to the organization.

She found, however, that when she later surveyed consultants on their ability to apply the program, results were poor. Consultants were not given time to use the processes they had learned, and management was not supporting the project management process through employee evaluation and project evaluation. In short, line management was not brought in.

In this case, the CLO operated a centralized country-wide training team that was somewhat disconnected from the day-to-day operations of the consulting groups. Once she identified the lack of alignment with line management, she set out on a mission to create a better education and governance process to make sure that line management was intimately involved in setting priorities, reviewing content, and supporting the project management program. Again, a business unit signoff process would have been highly beneficial here.

4. Organizational Performance Improvement. The fourth phase of business impact is more subtle yet. In this phase, hopefully, individuals take the skills, knowledge, and judgment gained by the individuals in the course and transfer this value to the overall organization. This fourth stage is typically described as Kirkpatrick’s Level 4. While training programs focus on the skills and abilities of individual employees or customers, ultimately the benefit must be organizational.

What creates organizational impact? The two key factors here are alignment and management support. How well does this program align with other reinforcing values, programs, and processes in the company? Is it consistent with other management processes and measures? Does it use language and support processes that are well-known and widely used in the company? If it is inconsistent with values and management processes, it will fail at this stage.

Second, does this training program support and enhance a well-established management-driven business process? We hope it does. If so, not only will it improve the performance of the individuals, but it will also improve the operations of that process. If not, it may be an interesting and valuable course, but it will not be reinforced through organizational impact. The key here is for the training organization to build programs that are fully aligned with organizational business and known development strategies.

An excellent example of this situation is the management development program developed for a major accounting firm. The CLO was a highly motivated, creative training executive who developed a wide range of professional education and support programs to make sure that accountants at all levels had access to the latest laws and practices in corporate accounting. He developed a series of “learning channels” that include webcasts, conference calls, formal training, and group events that delivered a wide range of topical training conducted by both trainers and senior partners (Figure 4.3).

As the organization grew in the last few years, however, one of the bigger problems he identified was the tremendous need to hire new accountants and develop these people into future leaders of the company. The company was suffering from a lack of a leadership pipeline, one of the biggest talent challenges facing corporations today.

Figure 4.3 Accounting Firm’s Learning Strategy

By closely aligning with the business leaders of the firm, the CLO revamped the training curriculum into a series of programs (courses, events, development activities) they call the LEADS program, that integrates this curricula and a variety of programs into a complete career development program (Figure 4.4).

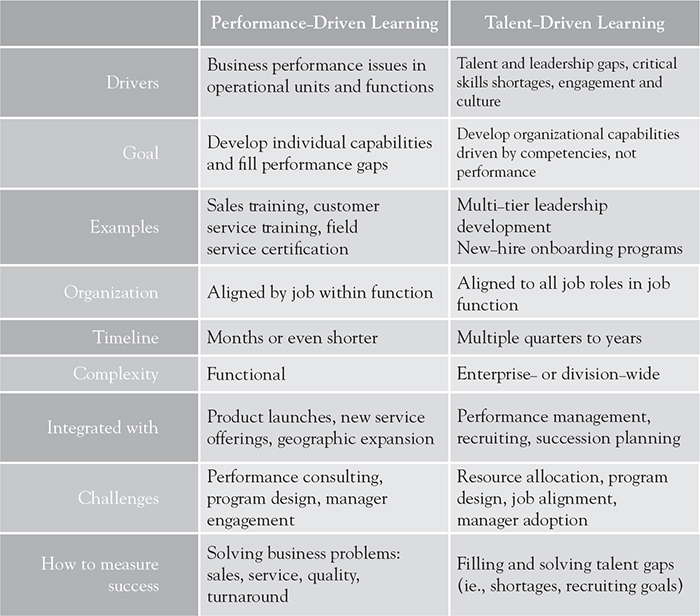

This program is clearly a “talent-driven learning program,” as opposed to a “performance-driven learning program.” It is focused on an organizational-wide talent challenge, not a specific business performance problem.

Performance Improvements for Talent-Driven Learning Programs. As we discussed earlier, there are two types of program: “performance-driven” versus “talent-driven.” The former are traditional classes and courses that focus on solving a particular performance problem. These programs may include new product rollouts, customer service training, quality improvement programs, systems application training, technical training, and others. They are often driven through a performance consulting process and are designed to develop specific skills, knowledge, and capabilities to solve particular problems.

Figure 4.4 Accounting Firm’s Talent-Driven Learning Programs

These programs are relatively fast to develop (months), relatively inexpensive to develop (tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars), and result in outcomes that can often be measured easily. For example, of you identify a problem with errors in the customer service process, you can develop a training program on customer service procedures that addresses these issues. You can then measure the “individual performance improvement” by looking at the reduction in errors and the “organizational performance improvement” by looking at the overall error reduction and improvement in customer satisfaction among customers who interact with the group that was trained.

On the other hand, talent-driven learning programs are very different. (See Figure 4.5.) These programs, like the one shown above, or a strategic leadership development program, or a long-term onboarding and career development program, focus on building talent. They do not focus on solving any particular performance problems, but rather on building organizational capabilities—developing better leaders, developing a larger pool of engineers, and so on. Ultimately, their benefits are measured in very different ways.

In the example of the accounting firm the benefits of their program are improvements in the leadership pipeline: more capable and confident managers ready to be promoted to partners. It also produces a better talent acquisition pipeline: new graduates look at the LEADS program as an incentive to come to work at the company it helps recruiters sell the company to high-powered accounting graduates.

These types of organizational benefits are far different from the typical “dollar savings” or “error reductions” we find in performance-driven learning programs. They tend to drive very large and different organizational benefits: improvements in retention, reduction in time to hire, improvements in employee engagement, improvements in the number of leadership candidates available for promotion, and improvement in job satisfaction. These are all areas that can be measured (the Gallup Q12 measures are good examples of surveys that measure these types of indicators), but cannot be measured through ROI or other Kirkpatrick approaches. In fact, in most cases, the organizational benefits of these programs are obvious.

Figure 4.5 Performance-Driven Versus Talent-Driven Learning Programs

So if you are working on measuring the fourth phase of our model, the “organizational improvement” phase, you should think hard about whether the programs you are measuring are performance-driven or talent-driven programs. If they are the former, you can easily find measures already being captured that will help you evaluate effectiveness. If they are the former, you are more likely going to want to talk with your senior VP of HR, head of recruiting, or other executives to look at the impact and effectiveness of these programs.

The Impact Measurement Framework®

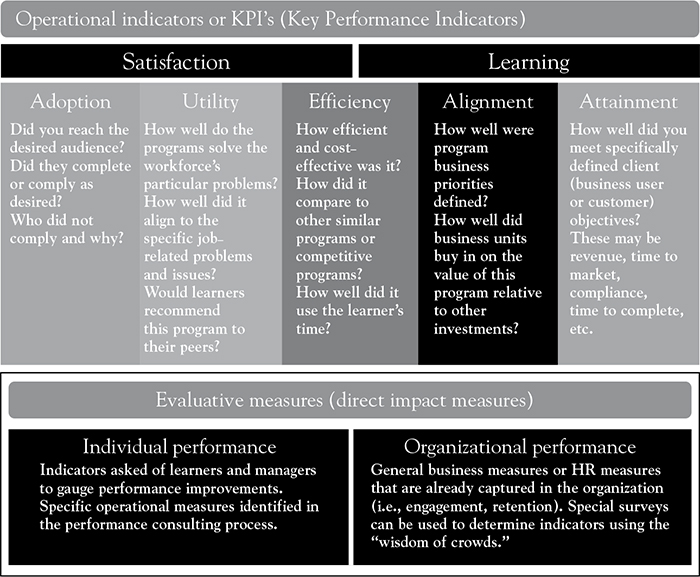

Now, having discussed the various elements in each of the four phases of training, let us turn directly to measurement. As Figure 4.6 shows, there are nine measurement areas in the bottom section of the framework that allow you to measure and monitor each of these processes in corporate training.

Let us now examine each of the nine measurement areas, or “measures.”

1. Satisfaction (Known as Kirkpatrick Level 1, or “Reaction”). Satisfaction is the granddaddy of all learning measures. We show it in phase two of the model, corresponding to the evaluation of program design, learning experience, and targeting and marketing.

As we discussed earlier, the word “satisfaction” has a specific meaning: it captures the learners’ direct feedback on various aspects of the training program. But outside of this concept, it is a very broad measure. We can measure satisfaction with many things: program materials, instructor, specific exercises, alignment with business problems, and more. In fact, the Kirkpatrick model greatly diminishes the value of the broad range of satisfaction measures. I am a huge fan of satisfaction questions, if asked correctly. We use them frequently in our research. We will describe how to use these measures in the implementation part of this book.

Figure 4.6 Bersin & Associates’ Impact Measurement Framework

2. Learning (Known as Kirkpatrick Level 2). Why do we embark on training except to teach? All instructional designers and instructors would like to know whether the learning objectives of a training program have been reached. Learning outcomes (that is, scores or demonstrated abilities from training) help training managers understand how well the program design worked, how well the learning experience worked, and whether the right audience participated in the course. While learning does not tell us anything about business impact, it clearly measures how well the program achieved its training objectives.

The key to measuring learning, of course, is to try to figure out what “learning” you are trying to achieve. And measuring this “learning” is far more difficult than one may imagine. For example, if your training program includes a technical curriculum (like LSI Logic’s storage training program for technical salespeople), the learning objectives may look like those in Figure 4.7.

These are clearly very complex learning objectives. They can really only be measured through on-the-job observation. In order to measure learning effectively, the program designer must understand what behaviors, situations, and exercises will actually simulate the real world. They must then use these activities to measure the learning outcomes.

Our research finds that only 35 percent of programs actually include explicit learning measures. Why is this? For two reasons: first, as I just discussed, it is hard to really measure learning. Second, and even more importantly, learning itself is not always the ultimate goal of many training programs.

In corporate training, learning is a means to an end. Unlike traditional universities and education, where learning results (test scores and grades) are used in an entire context of academic evaluation, corporate training is not really designed to “teach,” but rather it is a function that uses “teaching” to improve business performance. Therefore we caution training managers against overusing this as a way of measuring impact. Just remember that in a business environment, the definition of “learning” is very complex: trainers are not really teaching people how to score on a test—trainers are trying to teach people how to perform on the job. Real learning measurement should include on-the-job assessments and measurement of actual job performance under widely changing conditions.

Figure 4.7 LSI Logic Learning Objectives for Field Technical Curriculum

In The Blended Learning Book®3, the concept of “mastery” is defined as a combination of proficiency and retention, driven by experience. “Proficiency” refers to the ability to score well on a test. (For example, after taking the course on Microsoft Excel pivot tables, I scored 100 percent on the test.) “Retention” refers to the ability to retain and apply such knowledge under changing conditions. (The ability to create pivot tables and use them for large statistical surveys demonstrates this ability.) The “experience curve” is real—it takes time for proficiency and retention to lead to mastery. Training programs that include simulations of the real world try to build this experience quickly. Therefore the measurement of scores as a surrogate for learning only scratches the surface of this area.

Again, our research shows that one-third of organizations regularly measure actual learning—and we believe this is reasonable. Use this measure carefully; it provides excellent actionable information about the program itself, but far less information about the true business impact. Remember that it is the application of learning and its integration into the organization that drive overall business outcomes.

3. Adoption. Adoption is a critically important measure that is sometimes referred to as “butts in seats.” While it sounds tactical, it is, in fact, very strategic and actionable.

We define adoption as the percent of the target population who has completed a given program. In a sense, the adoption rate measures indicate how well the program was targeted and marketed, how well the program is being received, and what potential impact the program could have. Many training managers measure the success of a program by the percent of workers who have signed up.

Remember that one of the biggest challenges in corporate training is helping people find the time to prioritize the programs you build. Your “target adoption rate” should be reasonable. It is hard to expect 100 percent of all managers to attend manager training, for example, unless the entire organization considers it mandatory. When adoption rates are very high, it is a strong indication that your program is very highly respected.

Going back to our sales measurement example, in the marketing department, “adoption” is the equivalent to measuring “eyeballs,” “website hits,” “the number of people who opened a direct-mail piece,” or “leads.” It measures how well the target audience was actually reached. It does not measure “sales” per se, but it is one of the strongest indicators of sales, and “sales” rarely go up without the number of “leads” or “eyeballs” going up.

An example of how to use adoption measures: Suppose you are launching a leadership development program and the target audience may be all directors and above in the U.S. manufacturing organization. There may be 350 people in this target group. Your goal might be to reach 90 percent of these people within the current fiscal year. By establishing this adoption target (a very aggressive target, by the way), you will now be forced to develop an outreach campaign that may include a series of meetings with executives, various emails from you and the CEO, and scheduled classes that accommodate a wide variety of schedules. If, after the first thirty or sixty days, the adoption rate is low, then you have either a communications, alignment or scheduling problem. Or, worse, the program may have generated a poor reputation.

In some cases adoption measures are the most important ones you have. For example, adoption is a mission-critical measure for compliance programs (such as sexual harassment, safety, or operational quality). For e-learning programs, adoption is the only way you can discern whether learners can find the course and whether or not they are completing. (Completion may or may not be important in an e-learning course, but low completions in a mandatory program are clearly evidence of poor design or a technology problem.)

4. Utility. Utility is a new concept in our model. It is a word used to indicate the “usefulness” of the course to individual learners and their workgroups. It may appear to be a surrogate for an actual performance measure; however, it is actually an indicator4 of performance, which is much easier to measure than performance itself.

What we found is that “performance” measures are different from “utility” measures. For example, you may find that your favorite screwdriver is a very “useful” tool because it fits your hand well, fits well into most of the screws you have, is easy to fit into your tool chest, is colored easily for you to find, and is strong enough for your tasks. These attributes make it a tool you use frequently and recommend to others. On the job you may not find that you screw screws faster or better with this tool—but you perhaps tighten more screws and use it more frequently because it is so “useful.”

In other words, utility measures the “usefulness” of the training program and how easily and regularly you will apply it to your job. A well-designed “time management” course, for example, is considered useful—but may or may not drive improvements in measurable business impact. You clearly want your training programs to score high on this measure.

Utility can easily be measured through surveys and interviews. Survey questions that measure utility include:

• How useful was this course in helping you to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of your current job?

• How well do you feel this course will help you to reduce errors in your current job?

• How strongly would you recommend this course to others in your department?

Note that these questions, while qualitative in nature, were worded to provide you with quantitative indicators by using numeric ranges of answers (see the section on “Best Practices in Implementation”). You can tell that a course is “twice as useful” as another in this way.

5. Efficiency. What is efficiency doing in a measurement model for impact? Considering again that training is a support organization, efficiency measures play a tremendously important role. In fact, according to our usage research, cost is more frequently measured than learning results: almost 40 percent of organizations routinely measure the cost of each training program.

Efficiency measures in a vacuum are not very interesting. But once you start tracking them over time and comparing them to industry benchmarks (such as those in The Corporate Learning Factbook®), they are very actionable. These measures help you understand the speed, cost-effectiveness, and resource utilization of program development and delivery.

Efficiency is particularly important for many reasons today. First, remember that perhaps your biggest job as a training manager or executive is resource allocation. A focus on efficiency and the measurement of cost helps you best make these decisions. Some of the important measures that help you here include cost per hour of content development, cost per hour of delivery, and cost per hour of overhead (staff and infrastructure). If you understand the relative efficiency of different types of programs, you can more easily make decisions about which programs to outsource. Program allocation is a critically important decision—and when you decide to outsource a particular function, efficiency measures give you the benchmarks from which to select vendors and decide where your dollars can best be spent.

In addition, if you want to develop a business-focused learning organization, your management wants to make sure that the training budget is being spent in a cost-effective manner. Most training organizations are regularly asking for capital funding for LMS, tools, LCMS, and other investments. As training becomes more of a “shared services” organization and less of a “university,” there will be increased scrutiny of your cost of doing business. The CFO may wonder whether a given investment is resulting in lower overall costs and how the “cost per delivered hour” of the training programs compares with others in the industry.5 You should prepare for this type of analysis and start collecting cost and efficiency data now.

6. Alignment. The term alignment refers to the continuous process of making sure that training investments and programs are focused on the most urgent and critical business problems in the organization. As illustrated in the model, alignment plays an important role across the entire process and can be measured in many ways. We suggest the incorporation of some of alignment measures in the standard evaluations before, during, and after a learning event. Examples of alignment measures include the following:

Investment Alignment

• How well does the program allocation in the training organization reflect the business leaders’ perceptions of learning and development needs?

• How well do the training programs align with the organization’s broader talent management needs (for instance, the need to recruit and develop more engineers, need to develop mid-line managers, need to increase employee engagement, need to drive a high-performance culture)?

• How well do program managers understand the real business strategies and near-term goals of their assigned business units?

Process Alignment

• How well do the learning and knowledge within this program align with existing business processes (that is, do the processes or programs detailed in the programs match with the reality of how these processes are actually implemented)?

• Are the skills and techniques being taught reinforced through established processes (for instance, are there other tools and systems that agree with and reinforce the materials being taught)?

• Is there a performance plan associated with this learning program? Do managers, for example, understand the need to integrate these learning programs into employee development plans? Is there a way for such integration to take place?

Management Alignment

• How well do line managers and executives understand the value of this particular program? Do they even know about it?

• Do they understand the program’s value, where it fits into their business process, who should attend, and the prerequisites?

• Do managers understand the course material itself, so they can reinforce it on the job?

• Will they notify and encourage their employees to attend?

Job Role Alignment

• Are there clearly defined job roles targeted for this program? (For example, are all new managers in production engineering expected to take this course?) We call this element “audience targeting” in The Blended Learning Book.

• If so, are the program elements clearly aligned with the job roles and responsibilities as they exist today? For example, are the terminology, grade level, and learning fidelity of the course consistent with the audience being targeted?

• Does the learning program itself have different branches or modules for varying job roles within the same function?

• Is it a part of a certification or learning track for the entire job role? If so, is this certification consistent with the job roles and levels in the organization?

Competency Alignment

• Does the organization have a defined competency model for the individuals targeted for this course? Are there existing competency models used by managers or leaders that the course should build on?

• Are there corporate values or principles that should be incorporated into the program?

• Is the course easy to locate when an individual or manager seeks to develop these competencies? Are there systems or documents that help managers find the right course when faced with a skills gap? (This is particularly complex in large organizations.)

• Does the program develop a set level of proficiency in these competencies that can be applied to a performance or development plan?

• Does the program integrate with the company’s performance management system so that completion of the program automatically updates an employee’s competency profile or performance plan?

Financial Alignment

• Is this program urgent enough so that managers will agree that it is a good use of the company’s resources?

• How well do the learning and development organization’s financial priorities align with the priorities in the business units?

• Would a line manager agree that the budget spent on this program is appropriate, given other priorities in his or her organization?

Urgency and Time Alignment

• Are the schedule and time commitment for this course aligned with the pressing and timely business needs in the organization? Are there enough sessions, kiosks, or other materials to let employees take the course without impacting their work environment in a negative way?

• Does the course take too much time away from employees’ time on the job?

• Is the self-study requirement too burdensome?

(Some of these issues are covered in the section, “Attainment of Client Objectives.”)

As illustrated above, there are many elements of alignment that influence program design, targeting, delivery, and results. We believe alignment must be monitored, tracked, and evaluated to make sure training programs are driving business impact. How this information is actually captured is discussed in the following section.

7. Attainment of Client Objectives (Customer Satisfaction). This measure is one of the most important of all: “customer satisfaction.” How well were the specific business requirements of the business user or manager met, whatever they may be? In some cases, the key customer goal is to deliver the program on-time and on-budget. In other cases the customer goal is to reach 100 percent completion by a certain date. In the Six Sigma methodology (discussed later), this is called the “voice of the customer”—and is often considered the most important measure of all. (See Chapter 8: Attainment: Measurement of Customer Satisfaction.)

8. Individual Performance. The term “individual performance” refers to the individual job performance of each learner who attended the program. This measure equates well to Kirkpatrick’s Level 3. How do you get a sense of individual performance improvements? First, if the program manager did an excellent job of performance consulting (needs analysis), the training manager will have specific job-level measures that can be impacted by the program. For example, if you are assigned to develop a program to “train the sales force in product A” you should try to establish “What is the volume of sales of Product A now?” and “What do you believe the improvement should be, after this course?” These questions can be answered in a well-designed “Business Unit Signoff Form” that we will discuss in the implementation section of this book.

We urge you to consider establishing these goals up-front—during the performance consulting process. It is at this point that you have the most attention from line management, and you can easily establish some sense of the magnitude of the performance problems and potential measurable improvements in the process. By doing this before program design, you can use these performance goals to help guide program development, and you have instant credibility when you start to measure results.

Another way to measure individual performance improvement is through your organization’s performance management process. While this is far more subjective, if you have a close relationship with the business units sponsoring the training, you may be able to build program elements that correspond directly to performance goals in performance plans.

An excellent example of this is the measurement process used by Randstad in their onboarding program. Randstad is one of the world’s largest temporary employment agencies, so their onboarding program is widely used by almost every new “employee.” The training organization has aligned the training program directly with the performance expectations of new hires during their first one or two years. (This process is discussed in Chapter 6: Measurement of Business Impact.) The Randstad case study is in Appendix I: Case Study A: Randstad Measures Onboarding.) If you are building a “talent-driven” program that integrates with onboarding, or leadership development, for example, it may be easy to identify specific employee performance goals your training can focus on. These will be easy to measure because they are already captured in the company’s performance management process. (For example, “employees who attended the ‘strategic planning process’ course were rated 32 percent higher in ‘strategic thinking’ in their performance appraisals than those who did not.”)

9. Organizational Performance. Ultimately, the goal of any training program is to improve organizational performance (or overall business metrics). This measure is similar to Kirkpatrick’s Level 4. Organizational performance may or may not derive directly from individual performance, by the way. This measure is the most difficult to capture because it is never directly linked to a training program.

In fact, one of the things I have found in my numerous discussions with training and HR managers is that often the ultimate benefits of well-built training programs are more cultural than the organizations realized.

For example, at Scottrade, the company developed a very focused online simulation program to help new sales representatives understand how to qualify and promote Scottrade’s services. The program is highly interactive, entertaining, and very business focused. As the program manager rolled out the program, they found that it did, in fact, dramatically improve the quality of leads being generated and the number of new accounts.

However, in addition to this result, this program had several other benefits. First, the sales organization reported that sales representatives were happier, more enthusiastic, more confident, and more engaged. Retention levels were higher. And when Scottrade started to describe the program to candidates, the hiring rates went up.

These types of benefits, while hard to measure, have huge organizational impact. Some of the common “unexpected” benefits of excellent development programs include:

• Increased level of employee engagement (which can be measured through Gallup Q12 and other employee survey tools)

• Increased level of retention, driven by higher confidence in their job roles (a measure that most organizations already capture and one that can easily be quantified)

• Increased level of flexibility and mobility in the workforce, driven by employees’ understanding that the company is both (a) investing in them and (b) making it easier for them to succeed in new roles

• Improvement in hiring rates, driven by job candidates’ desire to be part of an organization that will give them development opportunities and coaching to succeed

• Improvement in the organization’s employment brand, its market image as an employer. This brand has tremendous impact on the ability of the company to attract and select high-powered people.

While these types of benefits cannot always be tied to a performance-driven learning program, they can easily be tied to an onboarding, management development, leadership development, or career development program. Their financial benefits are very large (typically 10 to 100X the cost of the program). Also, if you are in an organization that feels the need to measure impact very carefully, many of these types of measures are already being captured by your HR organization.

What about ROI? As I said earlier in this book, we do not recommend using ROI to measure organizational performance. Let us explain why through an example from NCR.

An excellent example of the complexity of measuring organizational performance is a field-service training program that was carefully measured by NCR. The company has a field-service force, which maintains and repairs a wide range of computing and IT systems throughout the world. NCR has a series of in-depth certification programs for service technicians.

NCR decided to evaluate this program and used the typical ROI method. In the ROI analysis, the NCR program director decided that the best measure of individual performance would be time to repair (TTR) for individuals who attended the program versus those who did not. Presumably, those technicians who were certified should have shorter TTR measures than those who were not certified.

NCR captured TTR data across a large sample of certified and non-certified technicians, and analyzed the data. The company found that those technicians who were certified and scored well on their certification program (that is, scored high in Kirkpatrick’s Level 2) were, in fact, taking longer to repair equipment than those who were not certified. It appeared that “individual performance” was not leading to an improvement in “organizational performance.”

NCR also found that, in fact, the measurement process was flawed. The reason that TTR was higher for certified technicians was that managers were so impressed with the skills of the trained personnel that they were sending them to work on the hardest service problems—so of course the TTR for certified technicians was longer.

This example is included here only to illustrate some of the challenges in trying to measure ROI as an organizational performance measure. While it is an important option, we warn managers that, in many cases, this particular measure will be the most suspect and difficult to correlate to training; so we do not recommend focusing overly on trying to measure ROI as a measurement of training programs unless there is strong alignment with line management. Organizational performance will “derive” from training in many interesting and often unpredictable ways.

As discussed in Chapter 6: Measurement of Business Impact, the best way to measure organizational performance is to monitor business metrics that are already being captured.

Summary of the Framework

Figure 4.8 shows the nine measurement areas in an easier-to-read format. Satisfaction and learning, which are well understood by most learning managers and are most frequently measured, are shown at the top. Individual and organizational performance, which are the more difficult and less frequently used measures, are shown at the bottom.

To summarize, Figure 4.9 gives examples of specific measures for each measurement area.

Program Versus Organizational Measures

Figure 4.8 The Nine Impact Framework Measurement Areas

Figure 4.9 Examples of the Nine Impact Measurement Areas

The nine measures in the Learning Impact Measurement Framework are program-level indicators as well as organization-level indicators. In the beginning, companies may start measuring these areas at a program level. Over time, however, as more and more programs are measured in a repeatable way, the overall adoption, utility, efficiency, alignment, and attainment measures across the organization as a whole can be measured.

For example, at Depository Trust Clearing Corporation (DTCC) the organization believes strongly in the Six Sigma approach to measurement. They established a set of measures that are used to measure attainment of customer satisfaction. “On-time delivery” (measured in days late) is one of these measures. The organization scores each learning program on its “on-time delivery” metric and compares that against the “on-time delivery” average for all programs.

Other Important Operational Measures. In addition to the impact measures discussed, almost all training organizations measure a variety of operational indicators that monitor the operation of the training function itself. These include the measures of production, efficiency, job satisfaction, and impact of the training organization.

Typical measures include:

• Volume—Hours of training delivered, hours per training head count, hours per employee;

• Economic efficiency—Total spending per hour delivered, total spending per employee in training, total spending per employee;

• Time-based measures—Time to build a course, time from product launch to training availability;

• Quality measures—Number of bugs in courses, number of technical support calls;

• Utilization measures—Total enrollments, total completions, percent utilization of the course catalog, percent utilization of facilities and instructors; and

• Team satisfaction measures—Job satisfaction in the learning organization.

While there are many more, these are measures to be established as part of the operational strategy. These measures should be used by a “learning services organization” to provide actionable information about how to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the learning organization.6

How to Use the Measurement Framework

This Impact Measurement Framework is intended to be used for two purposes. First, it offers a way to help you categorize and prioritize what should be measured. It should free you from the limitations of the Kirkpatrick model. No organization measures every one of the areas in detail, but any high-impact learning organization should measure some of these. All nine of these measurement areas are business-oriented, actionable, and fairly easy to measure.

Second, the framework should provide a way to simplify the measurement process. By understanding the concepts behind each of these measurement areas (including satisfaction and learning, which, as assumed, will always be measured), assessments, evaluations, or processes to measure each can be easily implemented. We have tried to define them in a clear way with many examples of ways to measure each.

Summary of the Measurement Models

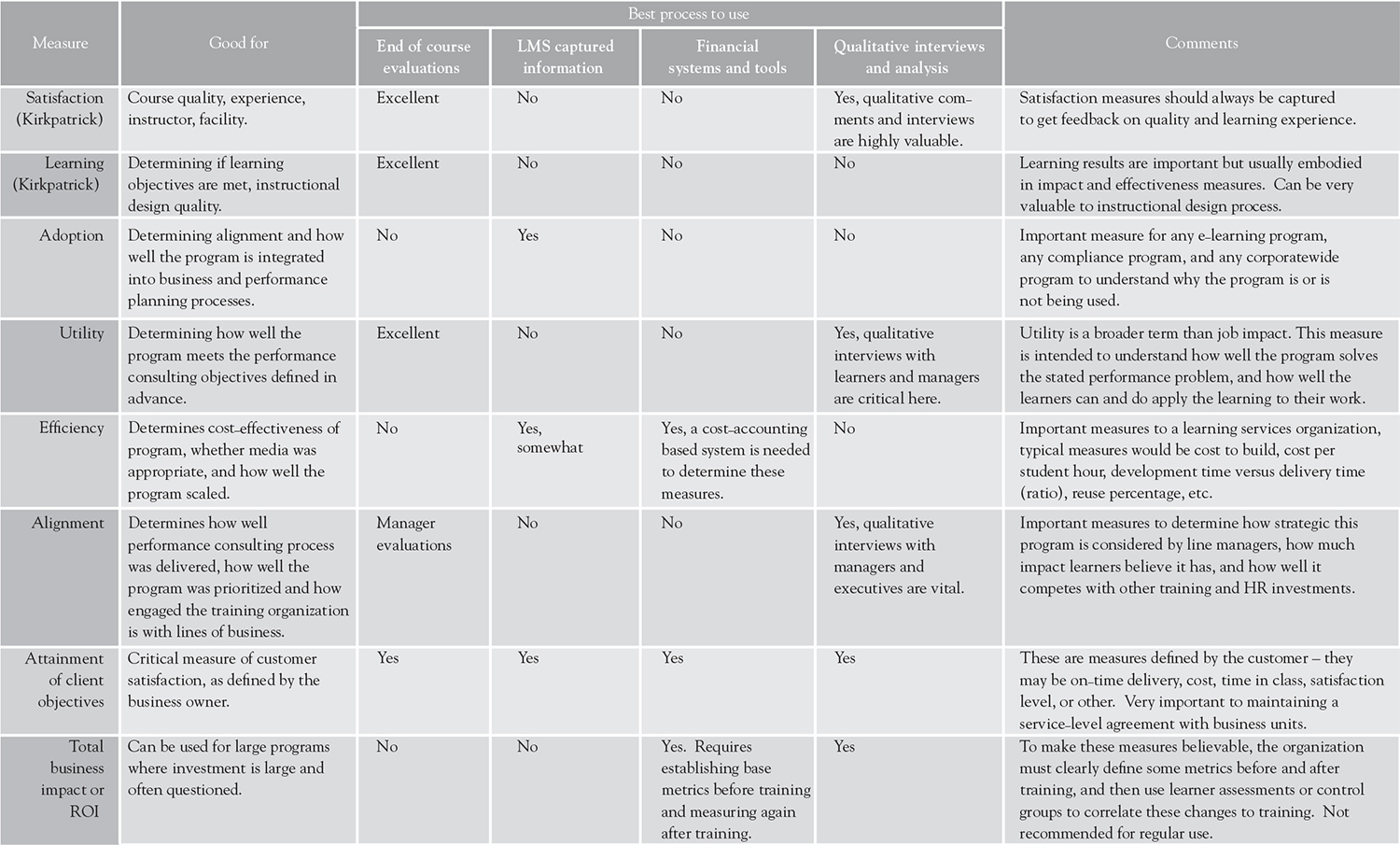

Figure 4.10 provides a summary of the Kirkpatrick and Bersin measures with specific examples of how and where each measure can be used. In this chart, “individual” and “organizational” performances are grouped together.

Figure 4.10 Summary of Measurement Areas

Notes

1. For a detailed discussion of all the options for the design of blended-learning programs, we recommend Josh Bersin’s The Blended Learning Book: Best Practices, Proven Methodologies, and Lessons Learned. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer, 2004.

2. For more information, see High-Impact Talent Management: Trends, Best Practices, and Industry Solutions. Bersin & Associates/Josh Bersin, May 2007. Available at www.bersin.com.

3. For more information, see Josh Bersin’s The Blended Learning Book: Best Practices, Proven Methodologies, and Lessons Learned. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer, 2004.

4. An “indicator” is a measure that is easy to capture and gives information that can be asserted or correlated to business performance.

5. For more information, see The Corporate Learning Factbook® 2007: Statistics, Benchmarks and Analysis of the U.S. Corporate Training Market. Bersin & Associates/Karen O’ Leonard, February 2007. Available at www.bersin.com.

6. For more information, see The High-Impact Learning Organization: WhatWorks® in The Management, Organization, and Governance of Corporate Training. Bersin & Associates, June 2005. Available at www.bersin.com.