CHAPTER 4

PRACTICE 2: EXECUTE

WITH EXCELLENCE

AS A LEADER, YOU MAY have a strong mission that you have communicated well with your team, and you may have a solid strategy for carrying it out. But no matter how visionary you are, you can’t truly be a leader unless you produce results. Fulfilling that strategy requires a deeply engaged team—and creating that team is the leader’s perennial challenge. Assuming you have an engaging mission and strategy, your next priority is to execute that strategy. Having a great strategy and successfully executing it are two very different things.

How often have leaders announced a great new initiative that dies a slow death? Most strategies fail, not because they are poor strategies but because they are never executed. Jim Huling, former CEO of a major US information technology consultancy and a current managing consultant for FranklinCovey’s Execution Practice, says, “You get everybody together in the annual company meeting and announce the strategy for the coming year. Everyone stands and claps and cheers, ‘What a great strategy! We can’t wait to get on board!’ As a leader, that’s your best moment. It’s also your worst moment, because from that point the strategy starts to collapse. It’s not that people don’t want to execute, it’s that they don’t know how—then they start to lose interest, and after a few months, it’s ‘What strategy?’ ”

It’s discouraging for a team member to get inspired and motivated about a big change—and then nothing changes. In one case, the leaders of a big nonprofit organization, one of the world’s largest charities, announced a major change in direction. There was a big event and a showy announcement party complete with banners, bands, balloons, and T-shirts for everyone. Everybody was excited, but they went back to work the next day and didn’t hear much about it after that. Occasionally someone would ask, “Whatever happened to that great new program?” They slowly disengaged, but at least they had the T-shirts.

Meanwhile, the leaders wrung their hands and wondered why the new program was failing. They rang up their regional managers, asking them with more and more exasperation to get on with it. The regional managers promised to do so, but then they went back to work and it was forgotten. After a year, the top leaders stopped talking about it altogether—it was too embarrassing.

This scenario might be extreme, but it’s more or less like this everywhere. How many carefully designed strategies are slowly gathering dust for lack of execution?

Occasionally there’s resistance to a strategy, and sometimes the strategy doesn’t fit the market, but by far the most common reason for strategic failure is a lack of organizational focus on the execution of the strategy. Think about it: Leaders give you a new program, a new goal, a new strategy, but your day-to-day work doesn’t go away, so you can’t give it enough focus. You have to keep doing what you’ve been doing (remember the mantra “more with less”) and meet the new goal, too. You’ve got to “get back to work.” Also, by asking you to do something new, the leaders are asking you to do something you’ve never done before. They’re asking you to change your behavior, which is the hardest thing anyone ever tries to do. Whether you’re trying to lose weight, learn the piano, win at golf, or execute a strategic goal with excellence, sustained success requires extraordinary commitment.

Wharton management professor Lawrence Hrebiniak points out that many MBA-trained managers “know a lot about how to decide on a plan and very little about how to carry it out.”1 So how do you get that extraordinary commitment from others? How do you engage them in new and demanding goals when they’re already struggling with the whirlwind of the “day job”?

It’s no longer enough to have a great strategy. The job to be done now is to get yourself and your team absolutely clear on the wildly important goals, and to discipline yourselves to execute with excellence and precision.

| THE JOB USED TO BE … | THE JOB THAT YOU MUST DO NOW … |

| To come up with a great strategy | To execute your strategy with excellence and precision to achieve required results |

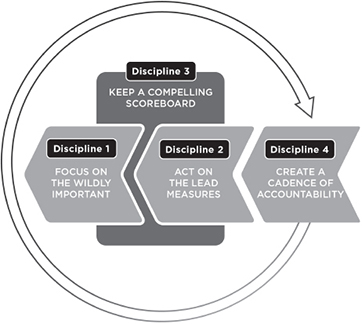

THE 4 DISCIPLINES OF EXECUTION™

To help you achieve these goals with excellence, apply the 4 Disciplines of Execution:2

- Focus on the Wildly Important

- Act on the Lead Measures

- Keep a Compelling Scoreboard

- Create a Cadence of Accountability

Focus on the Wildly Important

Most people are trying to do too much. To stay engaged with the real priorities, leaders need to carefully distinguish what is important from what is wildly important. A goal that is wildly important is one that must be achieved or nothing else will matter very much. Because human beings have limits, we can usually achieve one goal with excellence, but if we have two goals, it stands to reason we’ll do half a job on each. Ask us to reach five, six, or ten goals, and our chances of executing them all with excellence are zero. In investigating the great companies, Jim Collins found that most of them are highly focused on a few key goals: “When you develop your annual priorities, be rigorous about what your top few priorities are—and that should be a very short list … Work on one priority, and stop working on something that is of lesser priority.”3

It sounds obvious, but businesses have a way of piling up “must do” priorities, making it impossible to do a very good job on any of them. One recipe for disengaging people is to overwhelm them with things to do, all of which are “job one” and “top of the list priorities.” But if you unleash people to focus on one, two, or three wildly important goals—no more—they will sense the significance of what they’re doing and have a chance to win. There is tremendous power in focus. As you prioritize your goals, think about those things that must be done or nothing else matters, focus on those true priorities, and move lower priorities to the back burner.

Be sure to establish a clear and shared understanding of the goal. Leaders often assume the goal is understood by everyone, when in reality there’s usually wide and divergent understanding. Lawrence Hrebiniak reports, “I’ve done consulting where a major strategic thrust has been developed, and a month or two later I go down four or five levels and ask people how they’re doing. They haven’t even heard of the program.”4

Shawn reports, “I met once with a group of senior government leaders, the executive team for a newly formed agency with a new mandate. They had already met for days creating their strategic plan, so I did a little experiment: I asked each one separately to tell me the agency’s top priorities and key goals. I was fascinated by the response—they were all over the map! Every single one had an extremely different idea of what was wildly important, even though after days of planning they had assumed they were all on the same page.”

If a goal is wildly important, it’s worth being precise about it. That means you should formulate it in terms of where you are now (X), where you want to be (Y), and by when; in other words, “From X to Y by when.” For example, it’s not enough to have a goal to “lose weight”—you need to express it as, say, “From 195 lb. to 180 lb. by June 1.” Now you have a starting point, an ultimate objective, and a specific target date. It will be easy to tell if you achieve your goal or not.

In 1958, the US space program was significantly behind the Soviet Union’s. America’s goal was to “maximize our effectiveness in space”: nothing specific, nothing measurable, and something of a yawn. Then, on May 5, 1961, in a speech before a joint session of Congress, President John F. Kennedy proposed the goal of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth” by the end of the decade. This wildly important goal, “From the earth to the moon and back by 1970,” engaged and energized the entire nation. And it was achieved.

If a goal is wildly important and people know it matters most, their engagement goes off the charts—in fact, it’s tough to distract them. Formula One racers don’t answer their cell phones during the race.

When Tom Weisner became mayor of Aurora, the largest city in Illinois after Chicago, he confronted dozens of important issues. The Fox River district was blighted; the crime rate was sky high; gang violence had reached a high point with twenty-six murders the prior year; scores of businesses had fled the city, leaving an unemployment problem; and the city workers weren’t even taking down the annual holiday decorations (this last issue was a sore point with a lot of people). With so much on his plate, Mayor Weisner could have tried to “eat it all,” but he didn’t. He wisely surveyed his entire team of twelve hundred workers to choose no more than three “wildly important goals.” They would decide together what those three were.

Since no one had ever asked them before, the city workers had plenty of ideas. After repeated discussions with them and other civic groups, the city leaders chose three wildly important goals for the year:

- Reduce shootings by 20 percent.

- Reduce the resolution time for citizen requests from all city divisions by 20 percent.

- Revitalize the Fox River Corridor by approving a minimum of 650 new residential units and creating one acre of open space for the corridor.

Everyone agreed that if the first goal was not met, nothing else would matter very much. The image of a dangerous city was destroying everything. The second goal meant a lot to the citizens—to catch up on a huge backlog of requests would rekindle their faith in the city. The third goal was about turning a declining city into a revitalized city. These goals were wildly important to everyone’s future, and the people who set the goals owned them. They were engaged.

Act on Lead Measures

Once you have set clear “wildly important” goals, it’s time to define everyone’s role in achieving them. Each person must consider, “How do I contribute to achieving the goals?” Unless they all know the answer to that question, they will disengage.

In tracking progress on a goal, there are two kinds of measures: lead and lag. The lead measures track actions you set and take to achieve the goal. For example, consuming fewer calories each day and exercising regularly will lead to weight loss (as long as the laws of physics remain in place), so the lead measures are the number of calories consumed and the number of calories burned in exercise each day. The lag measures quantify the results. For example, if your goal is to lose weight, the lag measure is what the scale tells you about your progress. Tracking the lead measures is harder than tracking the lag measures, but you do it if you’re serious about your goal: If you do not hit the lead measures, you will most likely not hit the lag measure.

The task is to select a few lead measures that will have the most impact on the lag measure. You could make the mistake of selecting lead measures that make little or no difference. You could give up eating pastries, for example, but if you don’t limit your overall calorie intake, that action alone won’t matter much. Or you might choose a lead measure you can’t control, such as getting the company cafeteria to change its menu. To effectively reach your goals, personally or organizationally, you must choose lead measures you can control and that will make a true difference in the outcome.

As our team worked with Mayor Weisner and his team, it became very clear that cutting the murder rate was top of the list for the city of Aurora. The lead measure city workers adopted was to break up drug gangs by getting the gang leaders off the streets. Within months, the police had swept the city clean of twenty-one gang leaders. As for the third goal, revitalizing the Fox River district would require new, more attractive space for businesses and residents. City leaders set a lead measure to talk with fifty developers about new construction in Aurora—and by the end of the year, they had exceeded their goal and had ninety-five actively interested developers.

How do you decide which lead measures to work on? Here the expertise of the team comes in. The people on the front line probably know more about what actually moves the business than anyone else. The City of Aurora realized that reducing the murder rate was not the sole responsibility of the police force. Other departments could also play a role in achieving this goal. Municipal workers knew that crimes usually happened in poorly lit areas, so their lead measure was to ensure all burned-out city lights were replaced within three hours. They also knew that crimes tended to occur where graffiti had been painted, so they established a “remove graffiti within twenty-four hours” rule as a second lead measure. These are just two examples. Each department created its own lead measures toward the achievement of the ultimate goal.

One international company showed this principle in action as well. Brasilata, a manufacturer of steel containers and one of Brazil’s most impressive companies, needed to enact a plan to protect the containers and the contents inside them. Brasilata’s industrial-size cans are used all over the world to ship everything from grains to highly volatile chemicals. If their cans were dropped or mishandled, they could be damaged, which, particularly for its chemical-industry clients, could also be dangerous (and expensive, eroding their margins and causing serious legal issues). Building a better, more durable can became a wildly important goal for Brasilata.

Company leaders adopted the lead measure of getting ideas from the workers. They figured the more ideas, the better chance they had of improving the product. Because they engaged the work teams in the issue, the ideas poured in—thousands of them—and one of them really paid off. A worker on the manufacturing line had noticed that late-model automobile bumpers, when hit, will crumple instead of breaking open. When Brasilata applied similar technology to steel cans, the problem was solved, saving the company millions in damages.5

The takeaway is to get the team to define the lead measures. Call on their knowledge and their creativity, and watch them get fully engaged. It is critical for them to be involved in the selection of the final lead measure, as they will be responsible and accountable for acting on them—and all will be accountable to these measures.

Thinking back to the weight-loss example, what do you have control over—what you eat and if you exercise, or what number the scale shows? Unless you’re manipulating the dial on the scale, it’s the former. In the same way, you will disengage your people if you call them constantly on the lag measures—“Why aren’t you people hitting your sales quotas?” “Why is the crime rate still going up?” “Why are there still flaws in the product?” That is not leadership. The secret to achieving wildly important goals is not to set them and then hope people will somehow get them done. Instead, true leaders work with people to decide what lead measures are in their power and then hold them accountable for acting on those lead measures. People get engaged when they know they can actually make a difference.

Keep a Compelling Scoreboard

Shawn tells this story: “When I lived in Philadelphia, I liked to go down the street to the playground in my inner-city neighborhood and play basketball with the neighbor kids. It was fun to try to match skills. Usually we just fooled around with the ball, but sometimes we kept score. As soon as we started playing for points, something happened on the court: All of a sudden, the intensity level went up. Eyes narrowed, sweat poured, signals flew hard and fast, cooperation increased, and an audience gathered to cheer and groan. As long as we were just playing around, everything was mellow; but when we knew the score, things got serious. We were engaged.”

Like the neighborhood basketball players in Philadelphia, people are energized by “the score.” Everything changes when you’re keeping score, when you know if you’re winning or losing. You need a scoreboard so you can tell at a glance how things are going. The people in Aurora got excited when they saw they could “move the needle” on the crime rate scoreboard. As it started dropping, they became more engaged and more creative about moving it even more.

That’s why it’s crucial to keep a compelling scoreboard—a simple picture with only a few numbers on it. “We already have plenty of scoreboards,” you say. “We have numbers coming out of our ears.” But we’re not talking about the vast compilations of data a business runs on. Although those numbers have their place, we’re talking about the numbers that are wildly important—the lag and lead measures on the wildly important goals. All we need to see is the lag measure—“Is the murder rate dropping?”—and the lead measure—“How many gang leaders have we cleared off the streets?” These numbers tell us if we’re making a difference or not.

FranklinCovey consultants once toured a large aircraft factory where hundreds of workers were divided into small groups, each focused on making one part of an airplane. At each of these workstations, a computer monitor displayed huge amounts of data in tiny fonts. If you really studied these displays—really studied them—you could figure out what the numbers meant. We asked the teams why the monitors were there; most of them didn’t know, and the ones who did said they never took time to look at them.

So we asked the factory managers, “Why all the complicated data displays all over the factory?” They responded, “We want workgroups to be able to see the impact they’re making on the production process.” They’d missed a key execution principle. Imagine watching a sporting event on TV, a football match or a basketball game, with every single statistic related to the event displayed on the screen—but no way to see the score! That was the situation in the factory.

By contrast, one of our clients, another big manufacturing facility, posts giant scoreboards with just a few enormous numbers showing the company’s rate of progress toward the wildly important goals. But that’s not all—each shift that comes on can see whether or not they are hitting their lead measures. The plant leader told us, “These are tough union workers. They never come in early and they leave work at the exact second their shift ends. At least that used to be true—until we put up the scoreboards. Now we catch them coming in early and peeking up at the scoreboards to see what the other shifts are doing. When I caught some of them staying late one day, I nearly collapsed. They really care about the numbers on that wall.” The scoreboard is essential to engaging people.

The scoreboard is for the team, not just the leaders—that’s why it needs to be big and visible and constantly updated. People play differently when they’re keeping score. Chris McChesney, FranklinCovey’s execution practice leader, sums up the power of the scoreboard: “The highest level of performance always comes from people who are emotionally engaged, and the highest level of engagement comes from knowing the score—that is, knowing whether one is winning or losing. If your team members don’t know whether they are winning the game, they are probably on their way to losing.”6

Obviously, the scoreboard is a simple device, and it gives strategy execution a somewhat game-like quality. But it has a very serious purpose. Professor Hrebiniak reports that fewer than 15 percent of companies routinely track their strategic performance against plan; in other words, hardly anybody’s keeping score.7 Is it any wonder, then, that so many work teams, having no idea what the score is, are profoundly disengaged? The scoreboard enables people to track activities, compare results, and improve performance continuously. By watching the scoreboard closely, they can tell if their lead measures are well chosen. Are the lead measures actually having an effect on the lag measures? If not, it’s time to rethink them. By watching the few scores that matter very closely, the team can change strategy if needed. That’s what an engaged team does.

So what if you get everyone together and decide on the wildly important goals? You set your measures, you put up your scoreboard … and then watch the entire effort fall apart and die.

This could happen, unless you add in the next level of accountability, and here’s why: People will be excited at first. They will embrace the new goal because they’ve helped create it. They will commit to the new behaviors (lead measures) necessary to achieving the goal. The scoreboard will give them focus. But they need momentum to get it going. Unless the team comes together regularly and often to gauge progress, team members will disengage and wonder what happened to that goal. If you plan to drive from New York to California, you don’t just fill your car up once with gas and expect to make it all the way there. You start out making good progress, but eventually you’re going to need to fill up again. In the same way, you need to fill your workers’ tanks by holding them accountable and reigniting their enthusiasm by showing them how far they’ve come.

But how do you do that?

Wayne Boss, a professor of management and entrepreneurship at the University of Colorado Boulder, got interested in what he called the “regression effect”—the tendency of work teams to get really enthusiastic about new goals and strategies and then gradually disengage. Boss is a student of team dynamics, so he spent a lot of time watching teams come together, make plans, get fired up, and then forget the whole thing. He had watched companies do everything they could think of to psych up the workers about a new initiative: big parties, loud music, rap videos, giveaway programs, celebrity appearances, clown mascots running through the aisles. Most people enjoyed these events and went away fired up—but their behavior did not change. As Boss puts it, they invariably regressed: “During a two- or three-day intensive team-building activity, people became very enthusiastic about making improvements, but within a few weeks, the spark dwindles, and they regress to old behaviors and performance levels.”

Boss experimented with many ways to keep engagement high, but by far the most effective was to just meet regularly and often to monitor progress. We call it a “cadence of accountability.” Cadence is a “balanced, rhythmic flow” of activity, like a cycle that repeats itself.

If your team goal is in fact wildly important, you can’t afford not to have a cadence of accountability.

Create a Cadence of Accountability

The cadence of accountability is a simple, four-step process that will help you and your team cut through the clutter and chaos of the day-to-day and engage in your department or organization’s wildly important goals.

Here’s how the cadence works.

First, make sure everyone on the team can influence the goal. The goal defines the team—don’t include people who can’t “move the needle” on the scoreboard. In your first meeting, make sure everyone’s role in achieving the goal is clearly defined (you might want to do this in a private one-on-one meeting). Practice the first part of Habit 5 (“seek first to understand”) as you gather each team member’s perspective. Then ask, “What will you contribute?” Then, and only then, practice the second part of Habit 5 (“then to be understood”) and give your perspective. Then be synergistic (Habit 6) and forge the best possible solution and agreement.

Boss describes this role negotiation this way: The leader and the team member “clarify their expectations of each other, what they need from each other, and what they will contract to do.” Stephen R. Covey calls this contract a “win-win agreement,” in which all parties define what their “wins” are.

Next, meet with the whole team at least weekly (after all, we’re talking about a wildly important goal) to check progress. If you don’t meet for two, three, or more weeks, team members will disengage from the goal in the midst of everything else they have to do. This meeting is not your staff meeting—its sole purpose is to move the goal forward.

The agenda of the meeting is simple. Start by reviewing the scoreboard. Is the lag measure moving in the right direction? Are the lead measures having any effect? Are we where we’re supposed to be, or have we slipped behind? Should we reconsider our lead measures?

Then review the agreements, the things each team member committed to do the prior week. Celebrate successes and help people who are running into barriers. This is the value of a complementary team: If a team member encounters an obstacle, other team members might be able to help remove it. The leader in particular can do things no one else can, such as getting access to resources and talking to executives.

Finally, make new commitments for the next week. What’s the one thing each team member can do that will have the most impact on the measures? These commitments are recorded and shared and form the agenda for the next meeting. Keeping your commitments to your team can engage you more than anything else.

After studying hundreds of teams over a decade, Boss found that if these meetings are held on a regular basis (weekly, biweekly, or monthly), and follow the agreed-upon agenda, performance can stay high without regression for several years. “Without exception … group effectiveness was maintained only in those teams that employed [the process], while the teams that did not use it evidenced regression in the months after their team-building session.”8

Boss also found that the cadence of accountability is “most effective when conducted in a climate of high support and trust. Establishing this climate is primarily the responsibility of the [leader].” He explained that leaders must be ready to ask the difficult “why” questions if tasks are not completed, but they must do so with the attitude of helping to “clear the path.”

Teams used to this approach become semiautonomous. For example, a similar process is followed by grocery chain Whole Foods Market, where small teams are responsible for their own P&Ls and make their own decisions about improving them. Gary Hamel says, “They are held accountable for very challenging targets … This is not some romantic thing—’Let’s just give everybody more power.’ Equip them, give them the information, and make them accountable to their peers.”9

By using the cadence of accountability, you will give your team members the support and feedback they yearn for. More than 60 percent of the nation’s employees—especially the twenty-eight-and-under Millennials—say they don’t get enough feedback. Many managers give feedback only once a year: at performance appraisal time. That’s like a basketball coach telling the players at the beginning of the season, “You’re going to go out and play thirty games, and at the end of the season, I’ll evaluate your performance.” Frequent feedback relates directly to performance.

By following these principles and this process, you will do more to create a highly engaged, self-starting team than anything else you can do.

THE 4 DISCIPLINES AND TEAM ENGAGEMENT

Now, what happened to the city workers in Aurora, Illinois, as they started to live by the principles of excellent execution? The Aurora Beacon-News reported that “the city missed its first goal—shootings were reduced by 14.5 percent, rather than 20 percent—but the following two goals were achieved. Only a few departments fell short of the 20 percent reduction in response time, and the two big development agreements for projects on either side of the river exceeded the goal for residential units and open space.” Additionally, murders dropped from thirty to two; in the most recent year, no murders at all occurred in the city of Aurora.10 In this case, the result was not just an improvement in the “numbers.” It literally saved lives.

One more story.

For a century and a half, Leighs Paints has rolled out huge drums of the finest, most durable paint in the world. The firm, located near Manchester, England, is the world’s largest manufacturer of the heavy-duty paint used on ships, bridges, and oil platforms—structures that must withstand weather and rough use. But over the years, Leighs ran into real trouble in the marketplace—global competition has meant pressure on pricing and a tough market for raw materials. Worst of all, Leighs’ entrenched corporate culture wasn’t responding well to the intensifying demands of business in the twenty-first century. After several years of decline, the leaders knew the company was facing collapse. “It was that serious,” says CEO Dick Frost.

Now, in what can certainly be described as an amazing turnaround, Leighs is in great form again. Revenues are up significantly, market dominance is increasing, and the firm has been acquired by global powerhouse Sherwin-Williams.

What happened? We can understand the results if we look at it through the lens of culture. So what was the culture like before?

“Leighs was an old established business. It was a pointy, command-and-control, don’t-think culture,” explains Frost, also noting how employees were seldom asked for their opinions, and their contributions were limited to showing up and making paint. Many were completely disengaged emotionally and mentally from the company. “When asked how many people worked at Leighs, the black humor answer was, ‘About half of them.’ ”

Adds Roger Williams, a company director, “Leighs still practiced some of the industrial processes from the 1800s. There was a complete disjointment between what the management thought was going on and what was actually happening. Clients were unhappy with both product and service—nearly six hundred complaints were logged in one year. Employee satisfaction figures were painful. Finally, in the face of growing competition and declining margins, Leighs found itself hamstrung by a command-and-control culture of disengaged employees.”

About this time, Dick Frost became CEO of Leighs. An advocate of the 7 Habits and the 4 Disciplines of Execution, Frost introduced some ideas for change. He listened carefully to the workforce, trying to get a sense of the overall health of the culture. The company launched a change process with a new leadership style willing to think win-win, to listen, and to synergize. As they internalized the 4 Disciplines, energetic discussions produced wildly important goals at each level of the company. Line people took a hand in creating the company goals, a shared cadence of accountability was established, and leaders actively began to clear obstacles out of the way. Constancy of purpose developed across divisions of the company. “It used to be a joke,” explained Kaizen internal manager Paul Taylor, “that when you walked across the hall from Sales to R&D, you needed to bring a passport.” No more.

“The 4 Disciplines were useful to make sure we delivered,” explains Leighs HR director Mike Green. “Health Check Scorecards” were posted in every department so everyone could see what progress was being made toward the goals each week. Leaders changed their mindset about their roles—their job was to support the line people, not the other way around. An atmosphere of trust emerged.

Dramatic change did not happen overnight, but a few years after launching the new culture, Leighs Paints was showing quantum improvements on every measure that counts: steady gains in revenue, a fourfold decrease in the accident rate, and hundreds of new efficiencies added to the factory floor. “On time, in full” became the mantra for delivering orders, and teams constantly worked at moving that needle. One year, not a single employee grievance was filed. Meanwhile, productivity soared: At the start of the change process, each worker produced 19,466 liters of paint; within eight years that number had gone up to 38,606 liters (about a 100 percent increase); and operating costs had declined 20 percent.

Roger Williams says, “We continue to grow the culture. I think we probably put more time and effort into the culture aspect than we do into the financial aspects of the business. Now there are 262 people at Leighs Paints who turn up every day to do their best efforts for what they get paid to do. They feel the need to do it. We don’t have to tell them anything.”11

Everybody talks about accountability. The word makes people shiver, because it’s filled with fear. But the accountability created by the 4 Disciplines of Execution is personal; instead of being accountable for things you can’t influence, you’re accountable for a commitment you make yourself. The question we as consultants have our clients ultimately answer is, “Did we do what we committed to each other as promised?” When the answer is yes, the client’s group feels like a team, grows in respect and trust for one another, and becomes more and more deeply invested in the success of the team. Ultimately, the execution process is about real human engagement. And that engagement brings real results.

EXECUTING WITH EXCELLENCE:

INSTRUCTIONS FOR DOWNLOADING

Meet with the team and have the following discussions.