CHAPTER 2

THE FRAMEWORK: THE OPERATING

SYSTEM THAT BUILDS EFFECTIVE

LEADERS AT EVERY LEVEL

THROUGHOUT THIS BOOK, WE INVITE you to adopt a new leadership operating system and to “download” the paradigm shifts to your own mind. In doing so, you will discover the key to a culture like the one that raised Western Digital out of the mud.

Western Digital had an operating system based on the 7 Habits detailed in Steven R. Covey’s bestselling book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. By bringing this company the 7 Habits, we at FranklinCovey helped them instill a culture of proactivity and resourcefulness. Around eight thousand WD leaders and professionals had been trained in the 7 Habits; so their people were deeply rooted in a 7 Habits mindset long before the flood.

That’s why the leaders could say, “Be Proactive,” and WD’s workers pitched in while others waited to be rescued.

That’s why they could say, “First Things First,” and the company was helping workers dig out of their own homes as well as recovering the factory.

That’s why they could say, “Win-Win,” and immediately spread the word that there would be no layoffs: “We win together or not at all.”

Dave Rauch, senior vice president of Western Digital, said this: “We executed by tying our values to Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. WD’s strong culture enabled the flawless crisis execution that resulted in the production facility’s impressive recovery.” When asked why Western Digital responded so differently from other companies swamped by the flood, another vice president, Dr. Sampan Silapadan, said, “The 7 Habits are the key. Everyone knows this.”

The WD team succeeded because of the kind of people they are—and that is a reflection of the kind of leaders they have. Western Digital’s highly effective leadership produced highly engaged people, and you can’t calculate the value of that kind of engagement.

WD leaders did more than model leadership; they had made everyone a leader long before the flood. Employees were proactive, took ownership and responsibility, and acted accordingly when faced with a crisis. You, too, must make everyone leader, one who operates under the 7 Habits model. If you don’t, you will lose the ultimate competitive advantage: people who bring talent, passion, determination, and focus to the success of the organization.

SIX KEY PRACTICES TO SUCCESS

At FranklinCovey, we’ve had thirty years’ experience with hundreds of thousands of people in great companies, small schools, and whole departments of government. They come to us to gain insight and understanding of how to become highly effective organizations. We have six practices that show them how to do this, and it must begin with the essential mindsets—paradigms—that will enable them to thrive. We showed in Chapter 1 how the first shift in thinking is seeing that your people are your ultimate competitive advantage and that you must engage them before you can successfully move forward. We’ve also looked at how making everyone a leader and training them in the 7 Habits leads to a successful culture. Now it is time for you to shift your thinking in six key practice areas. Contrasted with the common practices of the past, these six highly effective practices compose the jobs you as a leader must do now:

| COMMON PRACTICES | HIGHLY EFFECTIVE PRACTICES |

| 1. Create and post mission statement in all public areas |

1. Find and articulate the voice of the organization, and connect and align accordingly (aka “Lead with Purpose” |

| 2. Develop a great strategy | 2. Execute your strategy with excellence |

| 3. Do more with less | 3. Unleash and engage people to do infinitely more than you imagined they could |

| 4. Become the provider/ employer of choice in your industry | 4. Be the most trusted provider/ employer in your industry |

| 5. “Create value” for customers | 5. Help customers succeed by creating value |

| 6. Satisfy customers | 6. Create intense loyalty with customers |

Why these six practices in particular? Each is based on fundamental principles that never change. The principles of proactivity, execution, productivity, and trust underlie every great achievement; nothing of lasting worth has ever been accomplished in human history without them. People who live by the opposite values—reactivity, aimless activity, waste, mistrust—contribute little to the success of the organization. The principles of mutual benefit and loyalty also underlie every successful relationship. People who live by the opposite values—indifference to others and disloyalty, for example—create no goodwill and work against the good of the organization. The common ways of thinking are often reactive and counterproductive; instead, we need this new model.

Consider: What kind of leader would you be if …

- no one but you felt a sense of responsibility for results?

- you didn’t understand your own unique competitive advantage—the combined power of your team?

- you failed to execute some of your most important goals?

- you didn’t fully leverage the genius, talent, and skill of your team?

- there was a lack of trust in you, between teammates, or in the organization?

- your customers had no clear idea of the unique value you bring to them?

- there was little loyalty on your team to you, each other, or the organization?

You can see for yourself why these paradigm shifts and new practices are vital. You can come up with many other success factors, but these six are inviolable. Leaders must be able to (1) find and articulate the “voice” of the organization, (2) execute with excellence, (3) unleash the productivity of people, (4) inspire trust, (5) help their customers succeed, and (6) engender loyalty in all stakeholders.

A paradigm is like an operating system for a computer. The machine will only do what the operating system allows it to do. If your paradigms are from the past, you’ll be using obsolete applications that aren’t up to the requirements of today.

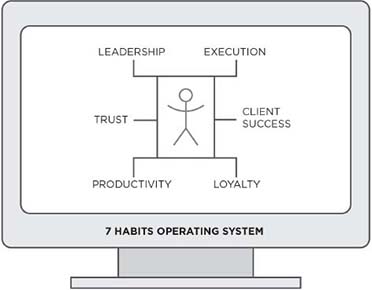

7 Habits Operating System

As the “7 Habits Operating System” graphic shows, you need an overarching “leadership operating system,” like the framework laid out in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, to run today’s applications—the paradigm shifts we’ve listed.

Each of these paradigm shifts and related practices is absolutely fundamental to success now. Each requires changing people’s hearts and minds in fundamental ways, and changing behavior is about the hardest challenge anyone ever faces (if you don’t think so, just consider how hard it is for you to change your behavior). It’s a great challenge, but the shift must be made, and this book will show you how.

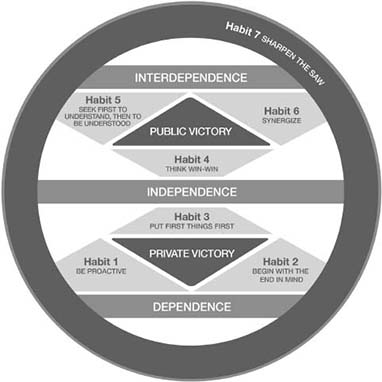

THE 7 HABITS OPERATING SYSTEM

So what are the features of this leadership operating system? What are the principles behind it? What are the attributes and behaviors of leaders who operate according to the 7 Habits?

- Proactive: They take initiative and responsibility for results (Habit 1).

- Purpose: They begin with the end in mind by having a sense of mission and vision that is clear, compelling, and infectious (Habit 2).

- Focused: They are highly productive and intensely focused on getting the right things done. They put first things first (Habit 3).

- Mutual Benefit: They “think win-win,” showing deep respect and seeking always to benefit others as well as themselves (Habit 4).

- Communicators’: They are profoundly empathic, seeking to understand people and issues and respectfully courageous when seeking to be understood (Habit 5).

- Synergistic: They value differences and collaborate to achieve the best possible results and outcomes (Habit 6).

- Continuously Improving: They demonstrate a personal and organizational commitment to continuous improvement and balance (Habit 7).

Obviously, anyone can have these attributes of a leader. It doesn’t matter what your title or job description may be. This operating system or framework allows everyone at any level in the organization to know what is expected of them and to know how to succeed personally, interpersonally, and organizationally.

Years ago, Stephen R. Covey isolated these basic attributes as the 7 Habits. His book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People swept like wildfire around the world, with millions of copies on millions of bookshelves everywhere, from pole to pole and from São Paulo to Saudi Arabia. The book’s message lingers in many people’s minds today because it has never lost its timeless appeal, and many organizational leaders have accepted the challenge of creating the conditions for turning everyone into a leader.

How do you make the 7 Habits everyone’s personal operating system?

GIVEN A CHOICE, WOULD PEOPLE

CHOOSE TO FOLLOW YOU?

The job starts with you—it’s time to evaluate your own leadership operating system. Jim Collins has said, “One of the most important variables in whether an enterprise remains great lies in a simple question: What is the truth about the inner motivations, character, and ambition of those who hold power?”1 That’s why this book is first of all about you. Whether you realize it or not, you hold power. You can be the pivot point between the past and the future for your group, team, or organization. It doesn’t matter if you are the most senior executive or the newest entry-level person. Regardless of your position, you can choose to lead and help create the future, or you can let the opportunity pass.

The real question is: What are your “inner motivations, character, and ambition”?

If you adopt the 7 Habits as your personal operating system, you can’t help but become a leader. You’ll behave the way a true leader behaves. But the 7 Habits are a matter of character: They operate from the inside out, which means you can’t fake them on the surface. You can’t pretend to be proactive or mission-driven or empathic with other people—they will spot your inconsistencies in a heartbeat. Practicing the 7 Habits means real introspection into your own character and motives. This doesn’t mean you need to be perfect at living the 7 Habits. People will forgive lapses as long as they know you’re trying.

To really understand the 7 Habits and how to incorporate them into your life, you need to read the book. We’re not going into depth on each habit here. But let’s look at the 7 Habits as a personal operating system for leaders.

HABIT 1—BE PROACTIVE:

TAKE INITIATIVE AND

RESPONSIBILITY FOR RESULTS

The first foundational habit of any true leader is to be proactive. It means that you habitually take responsibility. You take initiative. You act instead of waiting to be acted on. You’re resourceful. You don’t take no for an answer (at least not until there’s absolutely no way to get a yes). You act on the basis of your values rather than simply responding to the stimuli in your life.

Proactivity is a simple yet profound principle, but many people have trouble with it. It’s easier to be reactive and live on inertia than to stand up and lead. We’re uncomfortable with change and the people who want to change things. We discount our own abilities (“I’m not a natural leader,” “I don’t know what to do,” “I don’t have any influence around here”).

The Wall Street Journal observes, “Most managers will spend their entire work life reacting to orders from above, reacting to pressures and problems from below, or simply reacting to the insistent demands of a busy workplace … If all you do is react, you will fail as a manager. You may be good at solving problems that arise. You may be skilled at responding to the needs and requests of those you work for, or the people on your team. You may work long hours, be loved and respected by your employees, and be the very model of organizational efficiency. But you will not be an effective manager.”2

Effective leaders are proactive, not reactive. They are passion-driven and resourceful, and they find a way to achieve what matters most.

In the film Dead Poets Society, a group of boys starts classes at a private school in New England. On the first day, the wide-eyed and anxious boys proceed in a very orderly way from chemistry class to Latin to trigonometry, listening quietly to the standard initiation speeches from each teacher. Finally, they meet their new English teacher, Mr. Keating. He asks a boy to open the literature textbook and read aloud the introduction, a dry essay on the science of interpreting poetry. As the boy reads, it becomes clear that Mr. Keating doesn’t like what he’s hearing. He then stops the boy and asks him to rip the introduction out of the book.

The boys stare at him in amazement. He then orders them all to rip those pages from their books, as if the very presence of the essay alongside the works of Keats and Blake and Wordsworth and Shakespeare threatens their power and meaning. The teacher gathers the boys close to him and in a hushed, dramatic tone, declares, “We don’t read and write poetry because it is cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion!”

Being passionate is the essence of leadership. There is a science of leadership, but it’s secondary to the hunger and thirst leaders have to make a difference, to make a contribution that matters. If you are not passionately engaged in your work, you might ask yourself why. If others are not passionately engaged, it’s essential to find out why.

Great leaders have the “passion to see it through,” as Seth Godin says. They have “the willingness to find a different route when the first one doesn’t work. The certainty that in fact, there is a way, and you care enough to find it … This is a choice, not something you … get certified in.”3 While proactive people are passionate, they are also resourceful. Proactivity means you find a way.

More than a century ago, a young African American woman named Mary McLeod Bethune started the Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in Daytona Beach, Florida. The fifteenth child of former slaves, Mary grew up in deep poverty, but with her passion for learning, she pleaded for a place in school and eventually became a teacher. Recognizing that black girls of that time and place had little opportunity for an education, she became fired up with the idea of starting her own school for them.

Mary’s cash resources consisted of a dollar and a half, but that didn’t stop her. Her resources were limited only by her ingenuity, and that was unlimited. The only place she could find for her school was a shack next to the town dump, so she cleaned it up and used it. There was no money for supplies, so she made desks out of old boxes, pencils from charred wood, and ink out of boiled-down berry juice. Her desk was a packing case. “I lay awake nights, contriving how to make peach baskets into chairs,”4 she said.

The school opened in 1904 with five eager girls, six books, and the devoted Mary McLeod Bethune as the teacher. While teaching reading, writing, and math, she also taught them to be as resourceful as she was. What could they do to help support the school? One girl knew how to make a mattress by stuffing it with moss. Others knew how to bake pies. So they made and sold mattresses to their neighbors, and they offered pieces of sweet potato pie to the tourists who descended on Daytona Beach for the auto races. That’s how they paid the $11 monthly rent on their school. “I considered cash money as the smallest part of my resources,” Mary later wrote. “I had faith in a loving God, faith in myself, and a desire to serve.”5 Mary’s little school eventually grew into Bethune-Cookman University, thriving today with nearly 4,000 students and a $34 million endowment.

No one who knows the story of Mary McLeod Bethune can talk with a straight face about being short on resources. Our own ingenuity is the greatest of our resources, but only proactive people can leverage that resource. How resourceful are you? How resourceful are the people around you? Or do you live in a culture of helplessness, constantly restrained by a lack of passion and resources from the great contribution you are capable of making?

HABIT 2—BEGIN WITH THE

END IN MIND: GAIN A CLEAR

SENSE OF MISSION

The second foundational habit of any true leader is to have a clear end in mind—a vision or mission that inspires and energizes you. It also means that you have a clear purpose in mind for everything you do—initiatives, projects, and meetings. It’s based on the simple principle of knowing your destination early; even if you fall short, you’ll be moving in the right direction.

Some people say, “All this talk about vision is just drivel.” In fact, there’s a popular myth that when the legendary Lou Gerstner took over a floundering IBM, he said, “The last thing IBM needs is a vision.” He has since said he was misunderstood: “I said we didn’t need a vision right now. IBM had file drawers full of vision statements.” What was clear to him was that IBM wasn’t acting on its vision. “We weren’t getting the job done.”6

Everything made by humans is the result of a vision, from a potato peeler to the Mona Lisa. It’s designed in the mind first. Ironically, we know how to design potato peelers, but we’re not very good at designing a life. By just taking things as they come, we go at the most important things in life without much vision.

How often do we hear (and sometimes say), “They don’t know what they’re doing in the head office! This organization is drifting. Does anybody know where we’re headed?” Companies engrave empty, big-headed mission statements on bronze tablets: “Our mission is to maximize shareholder value,” “We exist to serve our customers with excellence,” “We endeavor to provide value-added solutions to exceed our customers’ expectations by continuously improving our unique integrated resources to stay competitive in the global marketplace of tomorrow.” So many mission statements are like these—void of passion, vision, or even sense. As Justin Fox, editorial director of The Harvard Business Review, wrote in The Atlantic, “It can be awfully hard to motivate employees or entice customers with the motto ‘We maximize shareholder value.’ ”7

It sounds so obvious: What is our real mission? Do we even have a mission? If so, does it make sense? Is there any passion at all, any aspiration in it? How will we measure success? It’s remarkable how many managers never even ask these basic questions; and if they do think about them they’re afraid to ask because, after all, they should know, shouldn’t they?

Even fewer ask themselves, “What is my own personal mission? What should I contribute here? What kind of a difference do I want to make? What will I remember about my work here? How will people remember me—or will they remember me at all?” Or do they see themselves as “job descriptions with legs,” giving little or nothing of their own minds and hearts to their work?

“The human race is filled with passion,” Mr. Keating said to the boys in Dead Poets Society. “But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.” He then asks, as did the great Walt Whitman, ‘The powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse.’* What will your verse be?”

What a wonderful and appropriate question for each of us to consider. What will our individual verses be? How will we make our contributions to the world?

Creating—or better said, discovering—your personal mission is a difficult but very powerful process. It will help bring clarity to the things you value, and will help define how you spend your time and the contributions you will make. It will bring a greater sense of meaning to your work. You’ll be able to help your team craft its mission. You might even influence your organization’s mission.

When Mary McLeod Bethune was campaigning for her school, she bravely introduced herself at a palatial vacation home in Daytona Beach and was received by the old gentleman who owned it. He enjoyed her gift of sweet potato pie and kept asking her back, which delighted her. She talked about her school in radiant terms, about the library and chapel and the schoolrooms and the lovely, uniformed girls. “I would like you to become one of the school’s trustees,” she told him.

One day his big limousine arrived unannounced at the school. The old gentleman got out, looked around, and saw nothing but a shed in a muddy field. One girl read aloud from a geography book while others peeled and boiled sweet potatoes for pie. Mary took off her apron and looked the man straight in the eye.

“And where is this school that you wanted me to be a trustee of?” he asked. He was obviously not pleased.

Mary smiled up at him and said, “In my mind and in my soul.”

After a moment’s hesitation, James Norris Gamble, the fabulously wealthy inventor of Ivory soap, wrote her a check. Overwhelmed by the power of her vision, Gamble provided her the means for realizing that vision for the rest of his life.

But the Bethune school was only a part of her vision. “The drums of Africa still beat in my heart,” she said. “They will not let me rest while there is a single Negro boy or girl without a chance to prove his worth.”8 With Gamble’s support and that of many others, Mary McLeod Bethune served as a remarkable agent of change for African American people. She helped found the National Association of Colored Women to help black people register to vote (which earned her a few visits from the Ku Klux Klan). She also became the first African American female head of a US federal agency, the Division of Negro Affairs, as a close advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor. Finally, she was the only black woman present at the founding of the United Nations.

Again, Habit 2 starts with you. What is your mission or vision of your own future? What will your contribution be in your current work role? Once you have discovered and carefully defined your personal mission, you will have a clear “end in mind” and you can begin to influence others to make their contributions, as Mary McLeod Bethune did.

Jack Welch said, “Good business leaders create a vision, articulate the vision, passionately own the vision, and relentlessly drive it to completion.” Your leadership starts with showing people “where you are going, what your dream looks like, where we are going to be when successful.”9

HABIT 3—PUT FIRST THINGS

FIRST: FOCUS ON GETTING

THE RIGHT THINGS DONE

The third foundational habit of any true leader is to prioritize so you’re giving the most and best attention to what’s most important. This is easy to do if you already know what the mission is; without the mission, you can’t tell what the most important things are.

And that’s the problem with many leaders. Because they’re unclear on the end state or destination, they can’t distinguish between what is “wildly important” and what is merely an “urgent priority.” Many so-called urgent priorities are neither urgent nor priorities; they are momentary distractions that actually prevent leaders from achieving the mission.

On a hot September day in 2005, a wildfire erupted in Topanga Canyon, California. Only a mountain ridge separated the huge fire from Los Angeles, and a major disaster seemed likely. One of America’s largest cities could have been consumed, but it wasn’t. The damage was limited because the Los Angeles County Fire Department had long since “put first things first.”

Most people would say that the mission of a fire department is to put out fires. The L.A. County Fire Department didn’t see it that way—their mission was to prevent damage to life and property. They didn’t want to fight any fires; they never wanted to deal with a fire at all. So long before the wildfire, they adopted aggressive goals: educating the public about making “defensible space” around their homes, clearing brush, removing fire hazards, and creating safe zones. They had pursued this goal intently, and as a result the Topanga Canyon Fire was far less destructive than it might have been. The department never has to fight a fire they’ve already prevented.

By contrast, most leaders spend most of their time “fighting fires.” You hear it all the time—people are “insanely busy” trying to keep up with urgent demands on their time and never catching up, never getting on top of it all.

So what is more important than fighting a fire? Preventing the fire in the first place.

That’s the “first thing” that needs to be put first. If the mission is to preserve life and property, the goal must be not to fight fires but to keep them from breaking out.

As The Wall Street Journal says, “ ‘What should we do?’ is the first question the manager must answer. ‘What is the mission of the organization I am managing? What is the strategy for accomplishing that mission? What are my goals for the future, consistent with strategy and mission? What are the overall goals for my team, and for each member of the team?’ ”10 Once the mission is clear (Habit 2), the leader’s job is to set and execute on clear goals for achieving it (Habit 3).

Remember the principle of “no involvement, no commitment.” When a leader merely dictates the team’s purpose without involving others in the process, that leader will find a low level of commitment and a high level of burnout from others. At the same time, leaders can’t just rely on the input of others as the sole basis of their direction. A leader is more than a census taker. It’s impossible to please all the people all the time, so don’t even try. Involve people in key decisions, let them help you clarify the direction of the team or the initiative, but be prepared to take a stand once you have gathered data and input. Your shared mission is your guide to determining what truly are the “first things.”

So what are your “first things”? What goals must you set to achieve your mission? Just as important, what goals can you say no to?

HABIT 4—THINK WIN/WIN: PROVIDE

MUTUAL BENEFIT BY RESPECTFULLY

SEEKING TO BENEFIT OTHERS

AS WELL AS YOURSELF

The fourth foundational habit of any true leader is to think win-win. The basic principle here is respect for others and for yourself. No arrangement in the business world—or in life, actually—can succeed unless all parties are winning, especially in the long term.

“But business is all about competition,” you say. “Whenever a customer makes a choice, somebody wins and somebody loses.” And you’re right, in independent situations—one side “wins.” But even in classically competitive situations, there are opportunities for interdependence. For example, airlines want you to buy their seats, but most will send you to another airline if a mechanical issue comes up. Virtually everything you do and every relationship you have depends on helping someone else succeed.

When the global banking crisis hit in 2008, it became almost impossible to get credit. David Fishwick, a prosperous dealer in minibuses, saw his business dry up overnight. Dave had spent his life building up his business and the town of Burnley in the north of England. “I had a lot of customers who bought minibuses on finance and who were decent, reliable, hardworking people that always paid back anything they owed,” he said “Suddenly, the credit crunch hit and these people I’d known for years couldn’t get a penny from the banks.”

Burnley, already struggling with 13 percent unemployment, was about to hit the wall. “Everywhere I looked, businesses were going bust and shops were sitting empty with big ‘to let’ signs over the door,” Dave said. “Every time a business goes bust, other businesses lose their customers, which pushes them even closer to the edge. The problem was that there was no money to get things moving and the banks certainly weren’t doing anything to help.” It was “lose-lose” everywhere you looked. But Dave Fishwick, a proactive, visionary leader, had a win-win mentality, and he decided to apply to open his own bank for the people of Burnley. “Why not?” he thought.

The government told him why not. Under the law, he needed a vast set-aside of millions of pounds before he could get a bank charter. Like any good proactive leader, he refused to take no for an answer and found a loophole: He could have his bank if he didn’t call it a bank. So he adopted the slogan “Bank on Dave!” and set up shop. Dave’s entire philosophy is win-win: He pays his depositors much higher interest than they can get from a bank, which draws enthusiastic customers. He gets to know every borrower personally and guarantees every loan he makes. So far his trust has paid off—only 2 percent of the loans he’s made are in arrears (traditional banks, which are seeing around 9 or 10 percent, would love those results).

For example, the Turners, a couple struggling to start a catering business, couldn’t get a loan from any bank. They went to Dave and he lent them the £8,500 they needed; but he did more than that. He advised them on their marketing and advertising, introduced them around to local businesses, and helped them set up a sandwich stand at a big construction site. The result: They attracted a lot of customers. As the Turners said, “We couldn’t have done it without the loan and Dave’s advice. He opened our eyes to what can be done.” And, of course, they are repaying Bank on Dave in full and on time.

In the world of Dave Fishwick, everybody wins—his depositors, his borrowers, and the local economy. He wins, too: “If nobody could buy a new minibus, that would mean no more David Fishwick Minibuses!” He is helping turn a lose-lose situation into a win-win success story.11

Dave understands the basic leadership principle of abundance—you don’t succeed unless others succeed, too, and therefore win-win is the only rational way for a leader to think. Do you consider yourself a “win-win thinker”? What evidence do you have? Would other people say that about you? Do you work in a win-win culture?

HABIT 5—SEEK FIRST TO UNDERSTAND,

THEN TO BE UNDERSTOOD: EMPATHIZE

IN ORDER TO UNDERSTAND

PEOPLE AND THEIR PERSPECTIVES

BEFORE SHARING YOUR OWN

The fifth foundational habit of any true leader is to seek first to understand other people before you try to make yourself understood. The basic principle here is empathy—listening with the intent to fully understand what they are feeling and saying. This allows a leader to get to the heart of the matter whether they agree or not.

Why is empathy a crucial habit for a leader?

Picture a business leader with no empathy for her customers. How long will she stay in business if she remains totally disconnected from their needs? How about a project leader with no empathy for his stakeholders or team members? Or a teacher with no empathy for his students? An aeronautical engineer with no empathy for the passengers on the plane she’s designing? A hospital administrator with no empathy for the patients?

Obviously, most leaders already have some empathy—the problem is not that they can’t understand people, but that they feel they must solve all their problems. Leaders have a compulsion at best to fix everything and at worst to smooth things over. It’s a natural urge to want to jump in and save the day, to be the answer to everyone’s problems. Of course it’s important to get to a solution, but you can’t solve a problem you don’t understand.

“I don’t have time to listen,” says the typical, notorious alpha leader. “I already know what the problem is and I know how to solve it. My brain is way ahead of theirs. Time is precious—why should I waste it sitting and listening to people?”

By contrast, when asked, “What advice would you give to a new chief executive?” the remarkable Angela Ahrendts, former CEO of Burberry, has a one-word answer: “Listen.” And what is the greatest mistake a leader can make? “Not listening.”

Under Ahrendts’ leadership, Burberry moved from a declining brand that had lost its appeal to a world leader in the high-end clothing market. Burberry revenues have tripled to more than $3 billion and shares have tripled in value. Burberry fashion shows draw a million viewers on YouTube and the company has fifteen million followers on Facebook, making Burberry the leading luxury brand in the world.12 Clearly, Angela Ahrendts knows something about leadership.

For Ahrendts, listening with empathy is the key leadership skill. “Just listen, just learn, just feel. It’s tough for type-A personalities to do that in this position, but you’ll be better off in the long run,” she says.

The resurgence of Burberry was totally unexpected, as the brand had been hijacked by counterfeiters and knockoffs—the famous Burberry plaid essentially meant nothing anymore. Angela quietly listened, putting herself in the position of the Burberry customer: “Where are the great old trench coats Burberry was famous for?” She listened to the sales force: “We can’t make near the commission on a stack of polo shirts as we can on one trench coat.” She listened to Millennials: “We want to see it online. We want to click on it and buy it now.” By reaching out to understand, Ahrendts knew what to do. She swept away hundreds of mediocre products, resurrected the chic, beautiful Burberry outerwear, and put the whole company online, sponsoring the first YouTube 3D fashion show in history. Burberry took off.13

Many new leaders start by imposing their vision on people, but great leaders allow empathy to shape the vision. “If I had implemented everything that I thought about the first thirty or sixty days, I can’t imagine where we’d be,” Ahrendts says. “The biggest mistake a leader can make is not listening, not feeling, not using your team. You hire functional experts for a reason. If I go to another country I hire an interpreter. If I go to court I hire somebody to defend me. It’s no different in business.” Why have a team if you’re not going to leverage what they have to contribute?

You practice Habit 5 just by listening—nothing else. You listen without interrupting, without judging, analyzing, or answering back in your head. You’re not thinking about what you’re going to say next. Instead, you’re listening closely both to what the person is saying and to what they’re feeling.

Your goal is to understand. If you’re a leader, that’s your job. You can’t connect with customers and colleagues without empathy and understanding. Only by getting into others’ shoes can you serve them in a customized way—the way they want to be served.

Empathy becomes even more crucial as leaders deal with a global marketplace. For example, empathy is extremely important in the Chinese workplace, where a leader is expected to interact daily with employees and customers. While Western Hemisphere CEOs can lock themselves in their offices for days on end, managers in China pay far more personal attention to staff and colleagues. As one expert says, “In China, leadership is a contact sport.”14

A European company with a joint venture in China sent them a leader with an excellent track record but no experience outside Europe. He was a good “numbers” man but a poor listener, paying little attention to the people around him. As McKinsey Quarterly described him, “The executive did not care about their observations and ideas, expected the staff only to follow his instructions, and did not listen to customer feedback. After two years, the executive was replaced, but the damage was done and the operation closed eighteen months later.”15

Only an empathic leader can unleash the potential of other people. Leaders without empathy are literally working in the dark because they’re ignorant of their team members’ passions, talents, and skills. You can’t possibly discover and capitalize on the motivations of another human being without knowing the person deeply. For instance, as Professor Heidi Grant Halvorson says, some people eagerly embrace big, grand goals, while others are wary and skeptical, preferring more vigilance and less risk. Unless you know the “motivational fit” of each team member, you’ll make poor choices about engaging their unique skills and talent. The only way to uncover that motivational fit is to listen and understand.16

Empathy is essential to effective leadership, and it can’t be faked. Stephen R. Covey said, “Leaders who take an interest in people merely because they should will be both wrong and unsuccessful. They will be wrong because regard for people is an end in itself. They will be unsuccessful because they will be found out.”

For many, empathy is counterintuitive. In fact, among the hundreds of thousands of people we have assessed on various leadership and effectiveness principles, this is the least practiced and, not surprisingly, most requested skill.

On a pragmatic level, full understanding earns the leader the right to be understood in return. Leaders can confidently share their perspective and align it to what they learned from their colleagues’ perspective.

HABIT 6—SYNERGIZE: LEVERAGE

THE GIFTS AND RESOURCES

OF OTHER PEOPLE

The sixth foundational habit of any true leader is to synergize with other people. The basic principle here is the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. A team of people with diverse skills and perspectives is always more productive and creative than each member alone can be, not to mention the lone leader trying to figure things out in isolation. One plus one equals three, or ten, or a thousand. Consider: How many pounds can one draft horse pull? Answer: About 1,000 pounds. How many pounds can two draft horses pull? Answer: about 4,000 pounds. In this case, 1 + 1 = 4. That’s simple math that is not always so simple. Why this result? By pulling together, each horse compensates for the other’s weaknesses. They complement each other; they fill in performance gaps. Each horse on its own is powerful. Together, their strength is remarkable!

We all pay lots of lip service to diversity, but in practice leaders tend to be territorial and defensive. Everyone hails the new merger for its “synergy,” but most mergers fail because synergy isn’t allowed to happen. (Marriages generally fail for the same reason.)

A large European construction firm wanted a presence in North America and acquired a cement company in the American South. Everyone looked forward to the synergies; the numbers looked wonderful, and the capabilities of the two firms fit together well. But year after year, performance fell further until the CEO turned in desperation to a study group from the Sloan School of Management at MIT to get to the root of the problem.

Their conclusion: “The anticipated economic synergies have not materialized because little attention has been paid to achieving psychological synergies.” They reported “open hostility” among the people in the acquired company; they “hated” their European owners and would not share data with them or even allow them on the premises without permission from their own CEO. “The goal of a merger is to have the component parts add up to more than they are worth individually,” the study group observed. “Obviously, this hasn’t happened.”17

Probing further, the study group found that the parent company didn’t value the very different culture, ideas, and input of the people at the acquired company. While the acquirer had hoped these people’s potential would be unleashed, they felt chained down instead.

When titles are conferred on people, they tend to become overcontrolling without realizing it. Their identity gets tied up in the phrase “I’m in charge here.” They value sameness, so they squelch ideas from the members of their team. They want order, so they enforce uniformity of opinion. They want their way, so they discount the divergent views of the team—and synergy is suppressed.

The great irony here is that synergy is the reason for having a team in the first place. No individual is like any other—each has gifts, talents, passion, and skills no one else can duplicate. Effective leaders leverage those differences.

Consider what happens when Airbus puts together a team of biologists, physiologists, artists, molecular physicists, graphic designers, and psychologists (and an aeronautical engineer or two) in a room and asks them to come up with the airplane of the future. What they envision will completely revolutionize air travel.

Imagine an airplane that mimics a human skeleton—it can twist, turn, spring, and vault like an athlete. Instead of wearing out, the plane’s muscular shell actually gets stronger with stress, just like human muscles do. Its parts look like human bones; the mechanism of a baggage compartment is modeled on your shoulder joints. When you sit down, your seat molds itself around your body to give you a customized ride. Instead of a dim, dense atmosphere, the cabin is spacious and bathed in natural light: The skin of the airplane transmits light and energy and even data, carrying music, video, and virtual golf games to the passengers. And the entire plane is organically grown from nanotubes—an enormous 3D printout weighing half of what our most advanced airplanes weigh.

“The airplane of the future will get its own consciousness,” the designers say. “It will be more like a living organism than just a collection of very complex technology.”18

This is the power of a synergistic team, where each individual member’s skills and genius and energies are leveraged to produce a marvel that no one could produce alone. On this team, every member is a leader.

“Wait,” you say. “How can everybody on a team be a leader?”

Imagine a team where everyone is a leader, where every member is proactive and visionary with clearly shared priorities. Imagine a team where everyone is looking out for the interests of one another, where they are intensely empathic and open to different views—in short, a team where the 7 Habits are the operating system. That is the team you need now.

Do you tend to welcome different points of view or discourage them? Are you territorial, defensive, or closed to the ideas of others? Are you suffering from the “not invented here” syndrome? Or is your team a model of synergy? Do team members feel unleashed or chained down?

HABIT 7—SHARPEN THE SAW:

KEEP GETTING BETTER AND MORE

CAPABLE, NEVER STANDING STILL

The seventh foundational habit of a true leader is to continuously improve your capabilities instead of letting them wear out. It’s based on the principle that if you neglect yourself, your physical health, your learning, and your relationships, you will become dull and useless, like an overused saw. Of course, any organization that doesn’t continuously improve its capabilities will inevitably fade away, but continuous improvement starts with you. The whole mindset behind Stephen R. Covey’s “sharpen the saw” habit is that continual learning and growth are as essential to the individual as to the firm.

Moulinex, once the biggest maker of household appliances in Europe, died a protracted death because it neglected to sharpen the saw. The company rose after World War II from the small workshop of Jean Mantelet, the inventor of the food processor, and by the 1970s had become a true industrial giant. Its assembly lines employed thousands of unskilled workers. Money poured into its coffers.

But because its leaders stopped learning, Moulinex stopped learning. The leaders assumed that their industrial model would go on unchanged forever and settled back to collect the revenue. Meanwhile, hungry companies in Southeast Asia were copying Moulinex products and making them even better and cheaper, using new qualitymanagement techniques to minimize costs and maximize quality. As their once-global markets dried up, the leaders of Moulinex sat passively and looked the other way. By 2001, the giant was bankrupt, a classic victim of failure to sharpen the saw.19

“Okay,” you say, “they asked for it. That’s not our mindset here. We’re flexible, nimble, alert to change, and constantly improving everything we do.”

If that’s true, then you are the exception. A global survey of companies in all major industries found that more than 60 percent have tried and failed to implement continuous improvement systems, and that doesn’t even count those who haven’t tried. Those who have succeeded cite leadership commitment as by far the major reason for their success, and those who have failed overwhelmingly point to (surprise!) leaders’ lack of commitment as the cause of the failure (88 percent!).20

Do you work for a “sharpen the saw” organization? Does your own team have a systematic approach to improving what you do? Do you have evidence that your core processes are getting better all the time?

And what about yourself—are you mentally and physically sharp? Are you a “continuous learner”? Do you work to keep your most important relationships healthy?

LET EVERYONE LEAD

Your first steps to building a winning culture that has embraced the 7 Habits and holds the ultimate competitive advantage are to adopt the mindset that everyone on your team can lead and accept that it’s your job to make them a leader, to inspire them to embrace their roles. You do this by establishing a framework—the operating system we’ve mentioned—for getting the job done effectively. This framework is ubiquitous and not role-specific. It demands that you “show up” and model the culture rather than talk about it in generic terms (or worse yet, “talk at” team members about it). It will develop high-character and high-competence leaders at every level of the organization. It will give everyone a common language and a set of behaviors they can depend on as they work to achieve results year after year.

Designing Your Culture Deliberately

Is your organizational culture working for you or against you? We invite you to design your culture deliberately. How much time and energy do we devote to strategic plans and initiatives, KPIs, goals, and project planning? Have you ever ignored or forgotten to address culture during a key strategic shift? Ever experienced a culture pushing back on a strategy or a changed management initiative? We recall hearing a devoted long-term public servant speaking to her team in the hallway after a new political leader’s election and “inspiring call-to-action” speech. She started the sentence off with, “Be respectful, and know that we can wait out any of this leader’s strategies . . . we’ve done it before and we can do it again.” That’s culture speaking back. Too often we leave it to chance and it pushes back hard.

A great culture must be leader-led and designed intentionally, and must have an established framework of behaviors and language that engages and aligns the performance of everyone in the organization. Everyone knows how to win. Everyone leads. Can you imagine if everyone in your organization behaved like a leader? What results would that enable?

The ultimate competitive advantage will go to those who adopt the paradigm that everyone on your team should be a leader. Too many see leadership as a position. But leadership is a choice, not just a position. Like the soccer players on Coach Dorrance’s winning team, each member of your team can take ownership of something. Each member can feel that they are making a worthwhile contribution.

How to Effectively Change Behaviors

The typical way to change people’s behavior is to reward or threaten them. This is what Stephen R. Covey called “the great jackass theory of human motivation—carrot and stick.” The problem with this approach is that it treats people like animals, and it works only on the surface and only temporarily. Like Tom, people who are threatened develop a paradigm of fear, and so they act out of fear. They will “work” for a company, but they will never give it their hearts. They will never speak honestly, contribute freely, or do more than is required.

They will never, ever tell you what they really think.

Yes, they will be motivated, all right—motivated to evade responsibility—but they will never be inspired. In today’s workplace, so many workers are afraid, and they act like it. They take little initiative, they avoid responsibility, they keep their thoughts to themselves—and they bring as little as possible to the table so they won’t get in trouble. This is the legacy of the Industrial Age, and it’s still with us. You will never capture people’s hearts by treating them like jackasses—yet that’s how most leaders try to lead.

The secret to changing behavior is to change paradigms and enact highly effective practices built upon these new ways of thinking. And that’s the purpose of this book: to replace unproductive paradigms with inspiring new paradigms and corresponding practices that will unleash new and extraordinarily productive behavior. That’s the job that you must do now.

The story of Western Digital proves that this job, while challenging, can be done, and that the results are dramatic. FranklinCovey partnered with this world leader in storage solutions to reach that ultimate competitive level, and we can help you, too.

Leaders as Owners

The most highly motivated people in any organization tend to be its leaders. They are the people who are responsible for results—they “own” the results, good or bad, so they’re highly committed to producing the best results possible.

HUMANIZERS VS. SYSTEMIZERS

Stanford professor Harold Leavitt beautifully described today’s leadership dilemma this way: “ ‘Humanizers’ focus on the people side of the organization, on human needs, attitudes, and emotions. They are generally opposed to hierarchies, viewing them as restrictive, spirit-draining, even imprisoning. ‘Systemizers,’ in contrast, fixate on facts, measurements, and systems. They are generally in favor of hierarchies, treating them as effective structures for doing big jobs. Humanizers tend to stereotype systemizers as insensitive, anal-retentive types who think that if they can’t measure it, it isn’t there. Systemizers tend to caricature humanizers as fuzzy-headed, over-emotional creatures who don’t think straight.”21

Most intelligent managers vacillate between the two as they develop a sense about which style to use in a given situation. Some try for a balance between boss and best friend, but it’s an extremely tough balance to strike. So managers keep seesawing between the styles. Somebody’s floundering over there, so you have to go micromanage them. Meanwhile, everybody else feels abandoned, and other people start to flounder, and eventually you’re micromanaging them. And so it goes, as you run from one crisis to another.

Professor Leavitt concluded that this typical approach to organizational leadership “breeds infantilizing dependency, distrust, conflict, toadying, territoriality, distorted communication, and most of the other human ailments that plague every large organization.”22

The problem, however, is not how to strike a balance between two dysfunctional styles of leading people—the problem is in your paradigm of a leader.

People who own things take care of them—they wash their cars, repair their homes, tend their gardens. They take care because they care. On the other hand, non-owners care little, if at all—who washes a rental car?

In organizations, the leaders are owners—of goals, projects, initiatives, and systems. A big challenge for leaders is to get other people—the non-owners—to care about those things. But followers, no matter how well compensated, no matter the promises, perks, or promotions, simply don’t care in the same way that leaders do. Followers don’t own anything.

Attempts after the middle of the last century to establish “participatory management,” originally intended to flatten hierarchies and make organizations more democratic, didn’t work. Just the opposite happened as hierarchies became more entrenched, silos popped up everywhere, turf wars became the norm, and politics nosed into the relationships between leaders and followers.

In our culture, leaders have always been defined by their titles. But as Stephen R. Covey said, “I don’t define leadership as becoming the CEO. A CEO is no more likely to be a leader than anyone else.” What Covey meant was, a grant of formal authority doesn’t make you a leader. Owning a title makes you accountable, but it doesn’t make you a leader any more than owning a pair of skis makes you a downhill racer. A title doesn’t automatically “en-title” you to anything.

Think about leadership in two ways: formal authority that comes with a title, and moral authority that comes with your character. As you look at the leaders you’ve known, you know some of them have had little influence despite their titles. Then there are the unofficial leaders everybody trusts.

The truth is, anyone can be a leader regardless of title or job description. Gandhi energized the entire Indian nation and won its independence, but never held a formal title. Every organization has an informal network of “go-to people” for wisdom, advice, and solutions. They are often neither officers nor managers, but they have earned informal authority because of their experience and influence.

In fact, having only a few leaders deciding everything just bottlenecks the whole organization. This is not news, but little has been done to change things. Management expert Gary Hamel says, “We still have these organizations where too much power and authority are reserved for people at the top of the pyramid … We have to syndicate the work of leadership more broadly.”23

Everyone Leads

So . . . if you want to motivate people, and you want your team to take ownership of their work, why not make everyone a leader?

It’s entirely possible to create the conditions where everyone can be a leader if you change your paradigm of what a leader is. When you no longer think of leadership as the sole province of a few select people, you realize that all people have primary leadership qualities that can be leveraged. Initiative, resourcefulness, vision, strategic focus, creativity—these qualities are in no way limited to the executive suite.

You could argue that the main job of leaders is to create other leaders. That’s how Jack Welch saw his job at General Electric: “The challenge is to move the sense of ownership . . . down through the organization,” he says. Dee Hock, the legendary founder of Visa, believed that leadership should be everyone’s job, a “360-degree” job, where everyone leads down, up, and around through their individual contributions and influence. According to Stanford University’s landmark study on CEO effectiveness, “Focusing on developing the next generation of leadership is essential to planning beyond the next quarter and avoiding the short-term thinking that inhibits growth.”24

But if everyone’s a leader, you ask, who are the followers? That’s easy. It’s like asking, “When it comes to shopping, who are the buyers and who are the sellers?” Everyone is both. The same person sells and buys, and in an organization the same person leads and follows.

What does it mean to have a culture where everyone is a leader?

It means that there’s a common leadership operating system, a framework, that everyone in the organization shares. Your devices have an operating system that makes everything else run; without it your devices are just dead pieces of plastic. In the same way, your work has standard operating procedures, and your organization has a certain way of leading and behaving.

What is your leadership operating system? Does everyone in the organization know how to succeed? How to behave? How to problem-solve and innovate?

As we’ve seen, in most organizations the current leadership operating system is flawed. Some are deeply flawed, where only big egos, tyrants, or passive-aggressives can thrive. But most leaders simply have an outdated paradigm. They’re doing their best to take charge instead of inspiring others to take charge.

Looking at the early structure of information technology is helpful here. In the old world, a big, master mainframe computer dictated to subservient computers, which simply did as they were told. That day is long gone. Now we all have our own smartphones, laptops, tablets—all connected to clouds brimming with information (much of which didn’t even exist yesterday) that we can access with the swipe of a finger.

Similarly, to be “the leader” traditionally means to take the whole enterprise on your back—to be the mainframe. It’s an exhausting prospect. It’s also terribly ineffective, to say the least. Here you are, surrounded by people with enormous talent, capability, experience, insight, and ingenuity, while you pretend to be the sole source of those things. We’re still “leading” others as if we were back in an Industrial Age world. But now we’ve reached a tipping point where that paradigm just won’t work. It’s time for a totally new leadership operating system that frees everyone to lead.

Sue, who constantly travels for work, tells about an extraordinary leader she has met, Captain Denny Flanagan of United Airlines, and how he exemplifies the strategy and benefits of letting employees be leaders and owners. In this world where air travel is so often such a trial, she says no one treats passengers the way this leader does:

“At the end of a miserable twenty hours in an overcrowded gate at the Chicago airport, he was the captain who would either get us to Orange County before the airport closed for the night—or not. The timing was critical and really tight. I was mesmerized when he took the microphone and rallied all the passengers. He told us he knew we had experienced a horrible day full of delays, and he wanted to keep the airline’s promise to get us to California; but he would need all of our help if we were to take off before the window closed in California.

“The next thing I knew the passengers were lining up, helping each other with kids, strollers, walkers—the plane was boarded more efficiently than I have ever seen, and cheerfully by every passenger. The flight attendants saw the captain holding babies, helping passengers get on, and loading their luggage, and they followed suit. About two hours into the flight I received a personal note from him thanking me for my loyalty. I still have it.

“In years of flying and millions of miles, I have never seen another airline pilot do what he did that night. I stayed on the plane after landing to meet Denny and to thank him for the best flight of my life. I will never forget him telling me that he basically discovered that his job was to ‘create a culture’ every three to six hours. He knows that every time he walks onto an airplane, he has the opportunity to commit, model, and demonstrate what excellence looks like. He also has a firm belief that his team members willingly want to do the same. He loves what he does and it is contagious.

“Later I discovered this is typical of Denny Flanagan. If there’s a diversion or a delay, he orders enough pizza or McDonald’s hamburgers for everybody on the plane. While they eat, he explains in detail why there’s a delay and jokes around with them: ‘By the way, this is my first flight,’ he says. Then, as the passengers make nervous noises, he adds, ‘Today.’

“Captain Flanagan raffles off prizes for his passengers. He calls parents of unaccompanied children to let them know their kids have arrived safely. With his phone, he takes photos of pets in the cargo area and shows them to their owners so they will know that their pets are safe and comfortable. He personally helps passengers in wheelchairs board the plane. He distributes his own business cards to frequent fliers with a handwritten note thanking them for flying with him. Nobody requires him to do any of these things. But in true proactive form, he says, ‘Every day I work from my heart and choose my attitude.’ ”25

Captain Denny Flanagan knows the tremendous difference between a leader and a person who has merely formal authority. Anyone who chooses to can be a leader, and the organization that knows how to help everyone make that choice will have an unbelievable competitive advantage, because an organization full of people like Denny is unstoppable.

MINING THE 7 HABITS

One example of an organization that is successfully turning everyone into a leader is Mexico’s MICARE/MIMOSA mining company. Seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day, eight thousand workers in MICARE/MIMOSA’s mines grind through coal seams two thousand feet below the surface of the earth.

Established in 1977, MICARE/MIMOSA’s only customer is the Mexican Federal Electricity Commission, which buys millions of tons of MICARE/MIMOSA’s coal to generate electricity at the nearby José Lopez Portillo electrical plant. From this effort, a full 10 percent of Mexico’s electricity needs are met. A few years ago, however, production was beginning to drop even as demand for electricity was rising.

According HR Manager Jorge Carranza Aguirre, “We were going through difficult times. We had to reduce costs while increasing production to meet higher demand. The problem was too much pressure, too much stress on people. Under these conditions, it was each man for himself. There was a lot of conflict between units and between workers and supervisors, and that created slowdowns. We did many good things, but we lacked unity and motivation.

“We had given the workers a lot of technical training and taught them how to operate the machines, but we needed to provide them with different kinds of tools. They needed to be able to manage themselves. When I heard about the 7 Habits, I realized this was the system I was looking for.

“The 7 Habits changed everybody’s mindset. At the top, we realized that if we wanted to be a first-world company, we needed a new foundational principle—that people make the organization, and to the degree to which we strengthen the people, we will strengthen the organization. We wanted everyone to be a leader.”

As we brought the managers and union leaders together around the 7 Habits, conflict decreased tremendously. Seeing themselves now as responsible leaders instead of victims, miners started taking initiative, setting goals, and collaborating on solutions to their own team and production issues.

The 7 Habits Operating System

Before long, the new culture was spilling over into the homes of the workers. People asked, “What are they doing to my spouse at work!? Now they’re coming home, and they want to make win-win agreements, they want to be more proactive, and they have a vision of what they want to do in life—things they never even thought of before.” Eventually, entire families joined the 7 Habits classes, and the culture of the community was transformed. When asked what had changed about the MICARE/MIMOSA miners, the wife of one miner replied, “Heart, heart, feeling . . . in every way, in the family and for their coworkers.”

Today the 7 Habits are painted on the outside of virtually every building in the mining complex. Miners paste 7 Habits stickers onto their safety helmets before they descend into the mines. MICARE/ MIMOSA has captured minds and hearts as the 7 Habits became everyone’s standard leadership operating system.

ENHANCING A WINNING CULTURE

Centiro is a cloud-based logistics software company headquartered in western Sweden. Their list of clients is impressive and includes iconic brands renowned for supply-chain innovation and effectiveness. Prior to their work with FranklinCovey and the 7 Habits, Centiro had a strong, even admirable culture. They had been designated one of Europe’s best places to work, and had a long track record of impressive financial results. CEO Niklas Hedin’s challenge wasn’t how to fix a broken culture—instead, it was how to take Centiro to the next level of performance. When our colleague, Henry Rawet, first met Niklas to discuss the 7 Habits, he noticed the powerful culture already in place. Together, they determined the 7 Habits could be the catalyst for building on this cultural foundation. Specifically, they saw it as an opportunity to establish the shared and common language necessary to create an enhanced culture of maximum empowerment and of getting people to work to their full potential, with better alignment between strategy and execution.

What makes Centiro’s story so interesting is the specific role Niklas took in personally owning the solution, and the fact that every employee regardless of position participated in the workshops. Our work with them began with their leaders. Both Niklas Hedin, the CEO, and Lisbeth Hedin, the Facility Manager, became certified to teach the material to their organization, thus making a very clear statement: “These principles are the foundation for how we behave, on an individual basis and an organizational basis.” There is no hiding your behavior when you stand in front of those you lead. Centiro’s leaders have consciously become models for the culture they want to create and reinforce. Niklas believes that as the CEO, one of his most critical jobs is to develop and sustain the winning culture.

EVERY CHILD CAN BE A LEADER

Even small children can become leaders. Thousands of schools have adopted the 7 Habits as a way to teach leadership to children. Usually, “student leaders” are a small group of gifted, outgoing kids who are always the class officers, the top athletes, or the leads in the school play. But at one school in North Carolina, all students are expected to be leaders. Every child is a leader of something. Organizing books, announcing the lunch menu, collecting homework, greeting guests, dispensing hand sanitizer—these might not seem like “leadership” roles, but leadership starts here. The children learn what it feels like to be responsible. They learn that being a leader means being a contributor.

Most students take huge pride in their responsibilities. Some don’t want to miss a day so they can fulfill their leadership roles. As they mature, so do their responsibilities: They take over marking attendance, teaching lessons, leading projects, mentoring other students, even grading homework. Every student can lead something. An autistic boy who struggles to keep track of time does small daily routines in the nurse’s office. He is so excited to fill his leadership role that he watches the clock like a hawk and is never late for his job. Another boy with a history of discipline problems is assigned to lead the office staff in doing several tasks once a day. He not only shows up for his “shift” but comes back two or three times a day wanting to know if he can help—and his discipline problems have evaporated.

These children will grow up seeing themselves as leaders no matter what positions they hold in their careers. They will understand the key difference between an office holder and a leader—between formal authority and real authority. This paradigm has had a profound impact on both academic performance, which has dramatically increased over the time the school has adopted this leadership framework, as well as a marked decrease in discipline issues. At the time of this writing, more than 2,000 schools have followed this model with similar results.

What was the result? Niklas told us, “It has done a couple of things. First, everyone knows why they are part of the organization. We’ve recently gone through a significant reorganization involving the entire leadership team. As with any change, this stirred the dust a little—after all, change can be unsettling even in the best of cultures. We’ve even had a couple of folks who have chosen not to be part of the organization as a result. Better now than later. Now people are better aligned. We have a process that has become part of who we are . . . it has ‘landed’ in the organization. The reorganization was met without a single negative comment. People have moved to their new teams and now can focus their entire energy on executing the strategy, with a new leadership team. We strive to operate in constant synergy.”

Niklas’ experience matches the advice of John Kotter, legendary Harvard professor of strategy: “The central issue [of leadership] is never strategy, structure, culture, or systems. The core of the matter is always about changing the behavior of people.” The way to change their behavior is to change their paradigms—to adopt an effective “leadership operating system”—and no priority is more important for you right now.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER:

INSTALLING THE 7 HABITS AS

YOUR PERSONAL AND LEADERSHIP

OPERATING SYSTEM

An operating system is a set of rules that governs behavior. With a strong operating system like Windows, iOS, or Android working in the background, you can smoothly run many applications, stay connected to the world, and feel secure.

A leadership operating system should do the same. It’s the set of rules that governs your behavior as a leader. You should be able to apply it confidently to any challenge or problem. It must allow you to connect to the world and stay relevant. You should have confidence that it works and will not fail you.

All of these standards are met by the 7 Habits. “How do you build leaders?” asks Jim Collins. “You first build character. And that is why I see the 7 Habits as not just about personal effectiveness, but about leadership development.”26 With the 7 Habits as your leadership operating system, you’ll be prepared to deal with today’s chaotic, unpredictable world and anything it can throw at you. Your connections to the important people in your work and personal life will flourish. And the security of the system is unquestionable because it is founded on principles that are universal and never change.

How do you install the 7 Habits as your personal operating system? Pretty much the same way you’d install an operating system on your computer—by downloading it. Read Stephen R. Covey’s classic book. Take the course. Find out how it feels to be more proactive, to have a clear vision for your own life, and to unload a bagful of useless “priorities.” Discover what happens when you approach people with a win-win mindset, when you stop trying to “fix” them and just understand them, and when you welcome their unique contribution to your life and work.

If you practice the 7 Habits, you won’t need a fancy title to be a leader—you’ll become a leader naturally.

Now, how do you help turn other people into leaders? As Gary Hamel asks, “What can we do to help teach people what it means to exercise leadership when they don’t have formal authority?”27 In other words, how do you install the 7 Habits Operating System into other people?

Whole teams and organizations have been transformed by getting educated together on the 7 Habits. Some leaders also have actively implemented the 7 Habits as a standard of behavior. Your influence might not extend that far right now. But as you model the 7 Habits in your own work, as the principles bear abundant fruit in your life, people will notice and your influence will inevitably grow. You’ll find them following your example—which makes you a leader.

But you can do much more than model the 7 Habits. You can do a mental “download” of the 7 Habits Operating System with your team. Follow the upcoming instructions carefully, and you’ll be doing the job you need to do now.

THE 7 HABITS OPERATING SYSTEM:

INSTRUCTIONS FOR DOWNLOADING

Here are seven commitments you can make right now—today—as you start your personal journey toward becoming a more effective leader who models to others how they can be a highly effective leader as well:

You can do more formal things to download this mental operating system, including reading the book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. You can also get assessments and training to implement the 7 Habits more deeply into your team or organization.

We have been influenced by many global leaders who have installed the 7 Habits Operating System with great deliberation and thoughtfulness. They have taught us the importance of a leader’s commitment to living the 7 Habits, to modeling them consistently, to installing systems in alignment with the principles, and to coaching performance consistently.