CHAPTER 4

Where Am I Going? (Purpose and Motivation)

LEADERSHIP PURPOSE CHALLENGE

In a world of information overload and centrifugal goals, employees and organizations often spin away from their basic sense of purpose and direction. Great leaders recognize what motivates employees, match employee motivators to organization purposes, and help employees prioritize work that matters most.

Lost in Wonderland, Alice approaches the grinning Cheshire cat to ask directions. When the cat asks where she is trying to go, Alice isn’t quite sure. The cat provocatively states the obvious: it doesn’t matter which road Alice takes if she doesn’t know where she wants to end up.

Clarity about where we want to go and why is crucial to a sense of meaning and abundance. Where are we headed? What do we live for? Why do we do what we do? In the last chapter we looked at what we want to be known for—the strengths and personal values that become our hallmark. In this chapter we look at how leaders identify the end results that help us know which way to turn and motivate us to keep traveling.

Of course, the destinations we refer to are not found on maps. They are about the visions that call to us, the laurel wreaths that appeal to us, the relationships that matter to us, and the ideas that enthrall us. They are about our values, our desires, and the needs of humanity at large. One person’s motivating destination is Olympic gold, while another’s is gold in the bank. One person envisions a renewable planet; another values most a shining friendship and another an enlightening idea. Ultimately the abundant life seems to call us to the impossible—traveling toward many such destinations at the same time.

In this chapter we will explore how leaders establish a sense of direction or purpose that contributes to meaning inherent in the abundant organization.

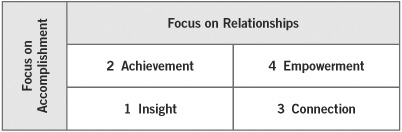

Places to Go: Four Categories of Purpose

We propose four categories of destinations to help employees find meaning in good times or bad. These categories build on work by Frankl and others. (See Figure 4.1.) Leaders with a clear sense of these four categories are better prepared to establish a compelling vision with a clear line of sight between the work and the world that receives the work, set and accomplish goals that add value across multiple scorecards, and articulate ideas that preserve the learning of the past and imagine solutions for the future.

FIGURE 4.1 Types of Individual Purposes or Motivation

We will come back to these leadership agendas later; first let’s examine the four categories they are built on in more detail.

Two dimensions characterize these categories: a low or high focus on accomplishment and a low or high focus on relationships with people. The resulting four categories are independent, so an individual can ultimately be low or high in each of the four categories independent of the others. Every category also embodies opportunities for either abundant, meaningful living or self-serving, unfulfilling existence. These four categories apply as much in Mumbai as they do in Paris or Sao Paolo. Let’s flesh out these four categories.

1. Insight

On the bottom left is insight. This category represents low interest in either external accomplishment or relationships with other people, but potentially high interest in self-awareness, the life of the mind, the world of ideas, or personal experience for its own sake. We might think of a monk meditating quietly in a cave, a camper enjoying a mountain hike, or a thoughtful student examining inner motivations and feelings. At its best, insight promotes awareness, thoughtfulness, creativity, and deep appreciation for what is good in this moment. This person looks at a baby’s first smile and thinks, “Look at that! I wonder what is going on in that little mind of his.”

There are also low-abundance versions of insight. At a less abundant level we might imagine a hermit who has withdrawn into a highly personalized but redundant world, a depressed individual ruminating over his inadequacies, or a couch potato in front of a television set. Low-abundance employees may drift through the halls of the workplace with little sense of passion for their work, doing the minimum, staying under the radar, going through motions with little sense of self-efficacy or even desire.

The movie A Beautiful Mind portrays a range of possibilities from this quadrant. In this film an extremely intelligent and creative professor develops groundbreaking mathematical formulas and theories but also wrestles with the demon of schizophrenia and must fight against delusions and paranoia. At his worst, this individual becomes lost in the idiosyncratic world of his illness. At his best he becomes a Nobel Prize winner whose passion for his theories and formulas sparks creativity and insight in others.

People motivated by insight might find deep meaning in the world of ideas, in creating theories about themselves or the world, or in being mindful, present, and aware of their moment-by-moment experience. They know instinctively that self-awareness is the ultimate virtue. In this category we remember that all we really have is the present moment and that in that precise moment even great suffering can be bearable. Those who value insight find beauty or wonder in small details, exciting connections, or hopeful realizations.

In an organizational setting, individuals highly motivated by insight may provide thoughtful reflection on problems or opportunities. They may be involved in research and development—the search for new and creative solutions to old problems. They may provide the symbols, models, and connective images that capture people’s imaginations and communicate powerfully. They are often motivated by the inherent value of a good idea and appreciate time to think and reflect. They remind us to appreciate the moment, learn from the past, or imagine the future. When things go wrong, their first instinct may be to say “Let’s stop and think so that we can learn.” Socially responsible individuals acting out of this quadrant focus on the data that shows the misuse and decline of the earth’s resources. They write articles, give talks, and suggest policies that reflect the importance of sustainability.

Organizations motivated primarily by insight may include religious, philosophical, educational, or research institutions; yoga studios, cruise lines, or recreational facilities; museums, theaters, or national parks. They include industries focused on leisure arts, self-awareness, education, and self-improvement.

Not every organization will find its primary mission in the world of ideas. But every organization needs the abundance that comes from insight.

As a leader, consider where in your organization insight comes from: Who are the proponents of organizational self-reflection, self-awareness, and self-improvement? Who has new ideas, makes new connections, or comes up with suggestions for new ways to do business? Who creates the symbols that will inspire and instruct? Who stops to relish the moment and reminds others to do the same? Who remembers to honor the past? Who can imagine the future? Is the role of insight understood, valued, and promoted?

2. Achievement

On the top left is achievement. In this category are individuals who find meaning and purpose in doing, accomplishing, or just checking things off the list for the day. This quadrant is about getting something done and may include activities that are highly competitive or that require risk taking, discipline, and resilience in the face of failure. High-abundance members of the achievement group might include an athlete in training, an artist perfecting a painting, or a corporate executive planning an aggressive growth strategy for the company. Someone motivated by achievement looks at a baby’s first smile and thinks, “How amazing! I wonder if she is developmentally on target for smiling.”

Not all high-accomplishment activities are abundant with meaning. When achievement is devoid of moral values or becomes an end in itself, it may be characterized by ruthlessness, even cruelty. The TV show “The Apprentice,” in which individuals compete in various business settings, suggests a high focus on achievement that becomes self-serving and callous. In the show competitors blame others for failures, see extravagance as the ultimate reward, and fear the boss’s condemning words, “You’re fired.” Such an approach assumes that there is not enough to go around and that one person can win only when someone else loses. The deficit-oriented culture of “The Apprentice” dominates many corporations today.

In contrast, Chariots of Fire is a movie about British athletes in the 1924 Olympic games, all motivated to excel at their sports. One of the athletes is discouraged from competing by his sister because she sees no value in sports and believes his destiny is to be a Christian missionary in China. He responds, “I believe God made me for a purpose—for China. But He also made me fast. And when I run, I feel his pleasure.” People motivated by achievement love to accomplish for the sake of accomplishment. Corporations in which achievement takes abundant forms are among the most successful and admired of companies.

People motivated by achievement might find meaning in simply getting things done and in winning. They generally enjoy improving and may strongly identify with their skills and accomplishments. Thus they like setting and meeting goals, getting feedback and having clear scorecards for measuring success, and being recognized for their accomplishments. They want measurable action plans that track results. In this category failure is an impetus for learning and there is always room to improve. These folks know instinctively that unless the organization provides real value and succeeds economically it simply won’t survive.

In an organizational setting, individuals highly motivated by achievement are generally hardworking and internally motivated. They often provide energy and drive to get the job done. They may flourish in competitive environments but are not necessarily trying to best others as much as solve problems and improve their own performance. Whether they are the rough carpenters who love getting the framework in quickly or fine craftsmen who relish detail work and fine finishes, people motivated by achievement take satisfaction in wielding their craft in ways others will respect. When things go wrong, their first instinct may be to ask, “What can we learn? How can we improve?”

Organizations motivated by achievement may focus on technology, sports, or the arts, but they will not just be along for a pleasant ride. They will be at the cutting edge, pushing the envelope of skill or design. They include industries focused on scientific progress, high return on investment, competition, or excellence in any domain. They may especially value high returns or good marketing but will get the biggest charge out of being among the best at what they do. “Winning” is their mantra, goal, and passion, and they write about and savor their triumphs and successes.

Not every organization will care to compete at the highest level. But every organization can benefit from the abundance that comes from achievement.

In your organization, where does achievement occur? Who are the proponents of achievement who push for learning and want to get better and better? Is achievement fostered by tailoring challenging assignments, providing clear feedback on performance (preferably with ways to actually count success or improvement), and recognizing improvement and success?

3. Connection

On the bottom right is connection, which is characterized by less focus on achievement and higher focus on relationships. People in this category find meaning in life through people they meet and interact with. Some will be energized by a few intimate relationships, others by looser ties with many people, but the common thread will be satisfaction and meaning through relating to others. This person looks at a baby’s first smile and thinks, “Oh, he likes me! Now we have a relationship.”

Again, there are low-abundance and high-abundance versions of this category. Lower-abundance versions might be people who are interpersonally needy or codependent or who like parties and social events but don’t develop real relationships of mutual trust, understanding, or care. These workers hang around at the watercooler but may be more invested in gossip or being liked than in getting the job done.

A higher-abundance version of connection might be a devoted parent, a trusted friend, or a skilled networker. Connectors find deep meaning in sharing life with other people, and people are the priority that gives meaning to everything else in their lives. At its best, connection motivates peace making, compassion, cooperation, and teamwork and fosters skill in listening, empathy, honesty, and service. Socially responsible connectors form advocacy groups, lobby for change, and rally support for environmental activism.

In an organizational setting, individuals highly motivated by connection grease the skids to help people get along at work. They consider the impact decisions will have on real people. They tune in to the needs and feelings of customers. They may have good intuition for solving interpersonal problems or creating systems to coordinate efforts of diverse groups. Under dire conditions, they endure so they can be reunited with or help those they love. They know instinctively that people matter more than things, more than policies, more than money, more than anything.

Organizations motivated by connection may include service-oriented industries of all kinds, clubs and sports leagues, neighborhood or civic groups, the social arm of religious groups, and extended family structures. They include industries focused on helping people meet, mediating conflicts, supporting families, and socializing the rising generation. Within companies human resource departments are often charged with concern for connection needs.

Not every organization finds its primary mission in getting people together. But every organization benefits from the abundance that comes from connection.

In your organization, where does connection live? Who are the proponents of people-oriented policies and programs? Whether or not your organization is explicitly service oriented, who pays attention to the needs of people both inside the organization and as customers and stakeholders? Any organization that does not provide real value to real people is unlikely to endure over time.

4. Empowerment

On the top right is empowerment, characterized by a high need for achievement that is channeled into high investment in people, especially in working to overcome human suffering. A high-abundance version of empowerment would be the TV show “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition,” where skilled designers and craftsmen use their talents and skills to redesign and rebuild an unworkable house for a deserving but impoverished family. They tailor the new house to the needs and personalities of the family, involving the whole community and working against the clock to finish the house in a week. The needs, feelings, and desires of people are foremost in such scenarios, but so are the skills, learning, and accomplishments of those who try to help. Other examples might be a skilled teacher who loves developing students, a talented political leader who finds creative solutions to real-world problems, and a hardworking religious leader who loves using her skills to empower others. An individual motivated by empowerment sees a baby’s first smile and thinks, “This is the hope of the future. Children will change the world.”

A low-abundance version of empowerment might involve overpowering others and attempting to enforce one’s will through intimidation or force. Even if real problems are being addressed, the focus would not be on empowering others but on self-aggrandizement or personal ambition. Low-abundance employees who are motivated by empowerment may be dominating or demanding, more interested in garnering power than in sharing it.

People motivated by the abundant version of empowerment might find deep meaning in social responsibility pursuits like finding a cure, reducing world hunger, or freeing political prisoners. They may also find great meaning in cleaning up a local park, serving food at a homeless shelter, or teaching a child to read. Empowerment may motivate someone to run for political office, become a high school teacher, or take over the lead of a troubled company. But high-abundance empowerment is not about accruing power over others; rather it is about helping others find their own voice, options, and personal clout.

In an organizational setting, individuals highly motivated by empowerment often gravitate to management/leadership or coaching/teaching positions. They like to see others succeed and want to make a difference for good. They may be good mentors, may be motivated to produce products that address a pressing problem, or may lead in charitable campaigns and community service.

Organizations motivated by empowerment may include political parties, nongovernment organizations, penal institutions, news agencies, volunteer groups, charitable organizations, or educational institutions emphasizing training and job skills. They include industries focused on medical advances and services, underserved populations, food production and distribution, ecology, energy production, and family services. Empowerment reminds us that suffering is unavoidable but that we can choose our attitude and response to suffering. We can ignore it, blame others, or give up in despair . . . or respond to it from our deepest values of compassion and courage. Empowerment is a powerful antidote to the societal plagues of isolation, despair, and ennui.

Not every organization will find its primary mission in humanitarian service. But every organization can benefit from a value proposition grounded in empowerment.

In your organization, where does empowerment percolate? Who are the proponents of social responsibility? Who helps everyone understand how his or her work is connected to the greater good and the needs of real people? Is there a clear line of sight between today’s work and the world’s problems?

Self-Awareness for Leaders, Employees, and Organizations

These four categories suggest four destinations that motivate people and bring meaning to life. As a leader, you can bring these motivating purposes into your organization at four levels.

First, know yourself. Know which of the four destinations or quadrants is motivating to you personally, be familiar with how these motivations may have changed over your lifetime, and look for ways to expand your repertoire to include elements of all the quadrants.

Second, know your employees. You can help employees in your part of the organization to identify the destinations or quadrants that are most motivating to them, helping them make sure the work they do ties into that motivation. Placing insight-driven employees into achievement positions or tasks will both frustrate the individual and limit the quality of work done.

Third, know your organization. You can help define for your part of the organization the motivations most relevant to your work. You can also articulate for others how each of the four quadrants contributes to bringing meaning, direction, and motivation to work.

Fourth, position your organization to have a socially responsible agenda. You can connect individual goals to broader societal goals through philanthropy and giving programs (be a company with a caring heart), through social activism (monitor and control use of carbon and other resources), and through work/life policies (offer employees control and flexibility for their work).

To identify what motivates you, your employees, and your organization, we highly recommend the following exercise (even if insight is not your strong suit):

PART 1

![]() For 20 minutes, write whatever comes to mind describing what your life would look like five years from today if you had become your best self and all your dreams were realized.

For 20 minutes, write whatever comes to mind describing what your life would look like five years from today if you had become your best self and all your dreams were realized.

![]() For an additional 20 minutes, write whatever comes to mind describing what your organization (or division) would look like five years from today if it had become the best it could be and all your dreams for it were realized.

For an additional 20 minutes, write whatever comes to mind describing what your organization (or division) would look like five years from today if it had become the best it could be and all your dreams for it were realized.

Repeat this exercise tomorrow to give your thoughts time to percolate.

If you have any interest in trying this exercise, which we hope you will, please do not read further until you do at least one of these writing exercises. You will glean a lot more information from Part 2 below if you do Part 1 first.

Psychologist David McClelland analyzed writing samples for evidences of what motivates human beings. He found that the needs for achievement, connection, and power showed up repeatedly in what people wrote, providing the basis for his theories about human motivation. While we won’t try to be that scientific here, take a moment to look at the scenarios you created in this exercise.

PART 2

![]() Looking through what you wrote, put an I for insight in the margin for any words from your success scenario that refer to creativity, imagination, symbols, self-awareness, balance, thoughtfulness, thinking for thinking’s sake, or having great ideas.

Looking through what you wrote, put an I for insight in the margin for any words from your success scenario that refer to creativity, imagination, symbols, self-awareness, balance, thoughtfulness, thinking for thinking’s sake, or having great ideas.

![]() Put an A for achievement in the margin for any words that refer to setting or achieving goals, learning so as to improve, developing skills, exercising resilience to keep trying at a difficult task, or gaining recognition for accomplishments.

Put an A for achievement in the margin for any words that refer to setting or achieving goals, learning so as to improve, developing skills, exercising resilience to keep trying at a difficult task, or gaining recognition for accomplishments.

![]() Put a C for connection in the margin for words referring to good relationships with others, spending time with people, meeting people or bringing people together, deepening relationships, feelings of mutual care and support, or being with people you love.

Put a C for connection in the margin for words referring to good relationships with others, spending time with people, meeting people or bringing people together, deepening relationships, feelings of mutual care and support, or being with people you love.

![]() Put an E for empowerment in the margin for words referring to solving world problems, making a difference, mentoring or developing others, seeing people succeed, providing resources or services to others, or gaining recognition for social responsibility.

Put an E for empowerment in the margin for words referring to solving world problems, making a difference, mentoring or developing others, seeing people succeed, providing resources or services to others, or gaining recognition for social responsibility.

![]() Count up how many of each letter you have. And yes, you can count double for items that have high value to you or that you elaborate on.

Count up how many of each letter you have. And yes, you can count double for items that have high value to you or that you elaborate on.

Once you have used the exercise to identify the destinations you find most motivating to pursue, you will know more about the compelling whys that support the hows of your life. You can then deepen, expand, and focus to increase your sense of purpose and direction. You can help employees do the same. Let’s explore these ideas further from a personal and leadership perspective.

Find the High-Abundance Version of Your Quadrant

As noted, each of these quadrants has low-abundance and high-abundance versions. The difference often is found in the moral values of the individual. Responding from our highest moral values tips the scales in favor of abundance. For example, think of a challenge you faced in the past that was extremely difficult for you—either at work, in your family, or in your personal life. As you think back on that challenge, what do you feel best about in terms of how you handled it? Are you most satisfied with how you kept your calm, showed honesty or authenticity, showed your sense of humor, forgave, learned from mistakes, or perhaps just kept going and didn’t give up? If you had it to do over again, what would you do differently (in 10 words or less)? What personal values show up in your answers?

Now think about the most pressing challenges in your life right now. Consider finances, family, health, losses, business downturns, tough relationships, transitions, etc. Now think of yourself looking back on this challenge from the perspective of many years from now. As you look back, what would you want to feel good about in how you handled the current difficulty? What values are most important to you to maintain and live from? What do you care most about in terms of your personal integrity in this situation? These are the values that saturate the high-abundance versions of the four quadrants—values like integrity, gratitude, humility, kindness, discipline, and compassion.

Now think about the most pressing challenges you face as a leader at work. How can you apply your personal values to these leadership challenges, helping others apply their personal values to meeting these challenges? When people apply their personal values to pressing business challenges, both individuals and organizations are more apt to succeed.

Expand into Other Quadrants

Even though we concentrate our efforts in one quadrant or another to start, great leaders must have at least moderate proficiency in all four quadrants to motivate all types of employees and respond to all types of challenges. A good place to expand is into the quadrant on the opposite corner from the one you prefer. For example, if you work primarily in the achievement quadrant, consider bringing into your life a balancing experience with investing more in connection, spending time with people regardless of their usefulness. Or if you love empowerment, consider adding a component of insight to give yourself time for rest, self-reflection, and fresh ideas.

One of us (guess who!) feels very comfortable in the insight quadrant and loves the world of self-exploration and reflection. But she has learned over the years that the comfortable world of ideas is hard to justify unless she moves across the chart to the opposite corner—the world of empowerment, where ideas become real in the lives of other people. Unless she is writing, speaking, serving, and listening to the real problems of real people, her grand ideas quickly become sterile and boring. Other people’s challenges challenge her to think differently about her own and push her to not only build on her strengths but also use them to strengthen others.

To some extent movement from one quadrant to another is a developmental process. We may need to concentrate our desires in one quadrant for a time, but over a lifetime can shift energy into new desires.

The other one of us (guess again!) majors in the quadrant of achievement, with a strong minor in insight. He spent many of his early professional years exploring exciting ideas, writing books, and developing a reputation as a thought leader in human resources and leadership. He loves crossing things off the daily to-do list and feels energized by his internal scorecard for accomplishments for the day. But in more recent years he is discovering the abundance that comes in investing more in family, friends, and community. Professionally he has moved more into both executive coaching and consulting with governments and international companies, trying to make a difference for good in people’s lives.

Few people start out with motivation in all four quadrants. To raise a family a person might concentrate on relationships for a time, putting achievement needs on hold. Another may invest heavily in achievement in the early stages of a career and then become more motivated by insight and the need for self-reflection later on. As we become aware of the limits of the quadrant we have been in, we may feel regret, even guilt, about not having balanced our lives better. But every life involves compromises and trade-offs, and few of us have the energy to support all four quadrants equally at the same time, especially early in life. Over a lifetime we can expand our repertoire of motivations and desires to include all four quadrants, even if we will always lean toward one or two.

It has been said that the abundant life begins when we give up all hope of ever having a better past. Many of us do not realize that clinging to the hope of a better past keeps us from finding meaning and purpose today. We covertly act as though if we are frustrated and unhappy enough about our regrets somehow life will take pity on us and undo them. Facing this false hope for what it is and willingly relinquishing it opens up the time frame in which real hope lies: the present.

In a similar way, a company cannot afford to be motivated indefinitely by one quadrant at the expense of the other three. Social responsibility initiatives for protecting the environment or serving the underprivileged (empowerment) must be informed by thoughtfulness and awareness of our limitations (insight). Human capital and employee initiatives (connection) must be tempered with the need for profitability, market penetration, and capital investments (achievement). Different divisions or employees may be charged with championing the whys associated with a particular quadrant but must remember that cooperation is needed to ensure that all the quadrants are accounted for in the organization’s overall structure and direction. Many European organizations measure their success by financial, customer/employee, and societal results—the so-called triple bottom line, often called the 3-Ps of performance, people, and planet. Corporate balanced scorecards help leaders match employees’ desired destination with their organization position.

Find the Right Fit

Leaders need to help employees and organizations find a good fit between the purposes that motivate the individual and the purposes that motivate the business as a whole. The higher leaders are in the organization, the more broadly they need to think about the purposes or destinations the organization seeks and the more they need to “walk in four directions at once” while keeping a clear sense of their overall purpose.

Sylvia was a talented human resources manager with an Ivy League education and a passion for women’s rights. She was hired in part because of her organization’s commitment to equality. But when Sylvia’s passion took over every aspect of her work to such an extent that she could talk of little else, her empowerment motivation ran amok, untempered by other business realities. While higher-ups valued her passion for equality, they also needed to attend to other purposes to keep the business profitable and contributing value for all of its constituents. Her single-focused why might have been a terrific fit in a government human rights agency, but it did not serve her (or others) well in her capacity as a business leader who needed to attend to all four quadrants.

While no organization will endure for long if it is not firmly grounded in empowerment agendas, ultimately the goal is to empower, serve, and create value for customers and stakeholders, not just to stroke the empowerment agendas of individual employees. Having said that, the more firmly grounded an organization is in the quadrant of empowerment—highly focused on both accomplishment and people—the more that organization can keep a clear line of sight between what it does well and the needs of customers.

A Leadership Agenda

While leaders need to walk in four directions at the same time, it is important to learn how to manage priorities and results across the four quadrants. Herbert Simon, the Nobel prize-winning economist defined the principle of satisficing. Satisficing suggests that some quadrants, though worth doing, may not be worth excelling at. There are things that are worth doing but worth doing poorly. Those quadrants that define our identity and purpose require our maximum efforts and energy. Like Kobe Bryant’s commitment to winning basketball games, these will be the essence of our game, the desires and strengths we rely and build on for success. Other quadrants we will satisfice, meeting basic criteria so these things won’t interfere with other goals rather than looking for the very best way to approach them. Like Bryant’s jump shots, we need to do these things moderately well but not superbly. In a world of limited resources of time, funds, and energy, it is crucial to know the primary motivations and purposes to which we will give our best effort and the secondary motivations and purposes that we will make do on. Then we to make peace with the compromises we all must make about where we spend limited energy.

Leaders can bring direction and purpose to their organizations and employees by asking:

![]() What are the insights we need to succeed as an organization? Who spends time thinking and reflecting on these insights? Who has responsibility for new ideas, learning from the past, and reflecting on our current situation? How do we make room for pondering, reflection, learning, and creativity?

What are the insights we need to succeed as an organization? Who spends time thinking and reflecting on these insights? Who has responsibility for new ideas, learning from the past, and reflecting on our current situation? How do we make room for pondering, reflection, learning, and creativity?

![]() What achievements and goals will keep us in business? Who spends time clarifying those goals, working toward their accomplishment on a daily basis, and acknowledging and rewarding their accomplishment? How do we promote efficiency and clarity to help people do their work with commitment and competence?

What achievements and goals will keep us in business? Who spends time clarifying those goals, working toward their accomplishment on a daily basis, and acknowledging and rewarding their accomplishment? How do we promote efficiency and clarity to help people do their work with commitment and competence?

![]() What types of relationships will help us get our work done? Who spends time investing in people, listening to their ideas, building congenial teams, caring about the individual, and keeping people connected? How do we build skills of communication, compassion, respect, and cooperation?

What types of relationships will help us get our work done? Who spends time investing in people, listening to their ideas, building congenial teams, caring about the individual, and keeping people connected? How do we build skills of communication, compassion, respect, and cooperation?

![]() What human problems are we trying to solve? Who spends time creating a clear line of sight between what we do and what our customers, stakeholders, and the world at large need? Who makes sure employees understand how the work they do makes a difference for real people? How do we communicate our empowerment agenda to all?

What human problems are we trying to solve? Who spends time creating a clear line of sight between what we do and what our customers, stakeholders, and the world at large need? Who makes sure employees understand how the work they do makes a difference for real people? How do we communicate our empowerment agenda to all?

![]() Which are the most pressing motivations of this organization, and where do they fall among the four quadrants of insight, achievement, connection, and empowerment? Which of the four quadrants will we excel at, and where will we satisfice?

Which are the most pressing motivations of this organization, and where do they fall among the four quadrants of insight, achievement, connection, and empowerment? Which of the four quadrants will we excel at, and where will we satisfice?

It is easy to lose track of our primary motivations and where we are going in the rush of work, the complexity of the world, or the press of adversity. But when we start wondering what the point of all our labor is, remembering the whys that delineate our destinations helps us put up with the hows. In the words of Viktor Frankl:

It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life—daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.

Summary: Leadership Actions to Articulate a Purpose

![]() Help employees recognize what motivates them (insight, achievement, connection, empowerment).

Help employees recognize what motivates them (insight, achievement, connection, empowerment).

![]() Match the employees’ motivation with the organization task they are assigned to perform.

Match the employees’ motivation with the organization task they are assigned to perform.

![]() Create an organization aspiration that declares a socially responsible agenda and translates that agenda to individual action.

Create an organization aspiration that declares a socially responsible agenda and translates that agenda to individual action.

![]() Help employees satisfice in those tasks that are worth doing poorly and prioritize tasks that are important to do well.

Help employees satisfice in those tasks that are worth doing poorly and prioritize tasks that are important to do well.