CHAPTER 2

The Making of Abundance

Abundance is neither a random act nor an isolated event. Leaders who intentionally create abundance at work build organizations that turn customer and investor expectations into daily employee actions.

Wrestling with Paradox

In Chapter 1, we introduced Vicki, whose early career enthusiasm is moderated by cutbacks and office politics; Raj, whose personal and family demands goals may temper his ability to grow his business to the next level; Grant and Shirlyn, for whom peaceful progression toward the twilight of their careers has been derailed by the current economic context; and Ivan, whose success has isolated him from himself and others. The individuals in each of these cases might say, “I’ve got abundance at work, all right. An abundance of headaches and hassles.”

Creating abundant organizations despite headaches and hassles requires leaders to struggle with paradoxical goals and values. These individuals must balance their professional dreams, career enthusiasm, family relationships, and retirement plans against business realities, office politics, the demands of growth, and larger economic contexts. Let’s face it: leaders who attend only to personal needs (theirs or their employees’) may create caring organizations that end up bankrupt. On the other hand, leaders obsessed only with making money will likely be socially and emotionally bankrupt if they fail at other things that matter: reputation, relationships, sustainable purpose, engaged employees, and the simple but invaluable experience of having fun at work.

Many insightful thinkers have attended to these issues. This chapter summarizes the remainder of the book by synthesizing and integrating diverse disciplines into our definition of how leaders create personal meaning and abundant organizations.

From Turnaround to Transformation

Meeting both organizational and individual goals is seldom easy. Leaders effectively connect the two when they create a clear line of sight from employee meaning to customer and investor confidence. McKell, the CEO of a large global bank, survived the economic demands of turnaround by streamlining staff, cutting costs, managing risk, divesting toxic assets, and stabilizing profitability. McKell then realized that to go forward he needed not only to complete the economic turnaround but to begin a more fundamental transformation as well—to change how both employees and customers perceived and felt about the volatile but sometimes faceless bank.

McKell and his executive team continued to efficiently manage the bank’s daily operations, but they also talked about where the bank was headed. McKell was a master of financial focus and discipline. But to put a friendly face on the bank he wanted to focus on feelings that shape meaning as well as facts that deliver results. This would mean not only continued efficiency but also relationships of trust with key clients and employees and better citizenship in the communities they served.

One of the executives jumped quickly on the bandwagon of good corporate citizenship with a proposal to invest in initiatives like microlending to underserved constituents. Another got enamored with building client trust and improving the bank’s reputation for personal attention. Another felt passionate about efficiency and excellence in management processes. All three goals were ultimately about creating a sense of meaning as reflected in how people inside and out felt about their experience with the bank. And ultimately all three could help the bank’s bottom line. After hours of debate McKell decided that only by embedding each of these goals in the other two would they shape a sustainable future identity. The individual values of these key executives needed to be coordinated and institutionalized for their goals to be realized.

As leaders they also needed to direct the emotional energy of employees, clients, and other stakeholders to these goals of citizenship, trust, and efficiency. Employees would need to gain a vision of how efficiency, client trust, and corporate citizenship could make their everyday jobs feel more like a personal mission and less like a duty to be endured. Clients and other stakeholders would also need a clear vision of what the bank was about and why.

When the executive team first became involved in the turnaround, they had a clear intellectual agenda for overcoming what was wrong with the bank’s operations. As they began to look at transformation, however, their agenda shifted to building what was right—abundance thinking and an emergent emotional agenda. In many ways, transformation is more difficult than turnaround. In a turnaround, a pending financial crisis demands attention and thus dictates behavior. In a transformation, greater emphasis must be put on creating meaning to capture imagination and shape future behavior.

Statistics on the national economy or the corporate cash flow focus our attention on the deficits that dominate our lives, including deficits in time and money resources. But other deficits can be even more crucial to our sense of well-being—deficits in purpose, satisfying connections to other people, challenging work, resilience, and delight. Such deficits can add up to a deficit of meaning. Overcoming these deficits builds the agenda of abundance.

Discovering Meaning

Abundance is not found in circumstances or events—in how big a raise we got or how many people report to us. Abundance is found in the value we place on those events and the way we interpret their impact on us. Meaning is not inherent in events; it is made by people. This is the good news and the not-so-good news. Good news: the meaning of our lives is not controlled by what happens—as Frankl discovered, we can find purpose, value, and also happiness in a wide variety of even unpleasant circumstances. Notso-good news: we have to work at this meaning-making process. It takes work to determine what work means, at either a corporate or a personal level. Leaders have the primary responsibility for this meaning-making process.

At a personal level, inner dialogues shape and construct this meaning. If I tell myself I’m not paid well because I’m not respected for my skills, I build a different meaning than if I tell myself how glad I am to work for an organization that is fiscally responsible. If I tell myself my boss’s criticism means he is trying to help me improve because he values my contribution and wants me to succeed, I build different meaning than if I tell myself his criticism is a forerunner to my getting fired for incompetence. If I see my company as a major contributor to solving the energy crisis, I have a different feeling about the value of my labor than if I am just crunching numbers for someone else’s selfish agenda. As the story goes, I feel differently about the meaning of my work if I see myself as a bricklayer than if I see myself as building a cathedral to God.

At a corporate level, leaders can help shape and construct the meaning employees assign to corporate realities, focusing corporate consciousness on opportunities instead of deficits. For example, when a corporation faces an industry downturn, people generally get nervous. Employees scramble to protect their budgets, make their own job perks sacrosanct, and push someone else between them and the corporate ax (remember Vicki’s story from Chapter 1). But when leaders in one technology company made clear to employees that every $50,000 in savings could save one job, people enthusiastically rallied around cost cutting. As a result, employees were engaged, cooperative, and constructive. They had a clear line of sight between how their actions could deliver company goals while saving the jobs of people they cared about.

Because finding meaning at work is itself hard work, and because meaning is very personal, we can’t promise leaders easy methods for replacing deficit thinking with abundance thinking. What we can offer leaders is a series of questions, which we will explore in the next section. We hope these questions will begin to structure conversations between leaders and their multiple constituents—conversations about what our organizations are trying to accomplish, why, and what those efforts suggest about the meaning of our lives.

These meaning-exploring questions are intended to produce the following outcomes:

![]() Increasing clarity about identity and signature strengths

Increasing clarity about identity and signature strengths

![]() Gaining a sense of purpose to understand better what motivates us

Gaining a sense of purpose to understand better what motivates us

![]() Managing work complexity through teamwork

Managing work complexity through teamwork

![]() Replacing social isolation with positive work settings

Replacing social isolation with positive work settings

![]() Identifying and responding to challenges that we care about and that engage us

Identifying and responding to challenges that we care about and that engage us

![]() Growing from change by learning and becoming resilient

Growing from change by learning and becoming resilient

![]() Building sources of delight and civility into our work routines

Building sources of delight and civility into our work routines

. . . and do all this within the fiscal constraints that help keep us honest about whether we are adding real value for customers, shareholders, and communities.

Why These Outcomes?

The questions that produce these outcomes have emerged from our reflection on two sets of ideas. First are the societal and business challenges or crises of meaning already laid out in Chapter 1:

![]() Declining mental health and happiness

Declining mental health and happiness

![]() Increased environmental demands that shape social responsibility, organization purpose, and individual motivation

Increased environmental demands that shape social responsibility, organization purpose, and individual motivation

![]() Increased complexity of work

Increased complexity of work

![]() Increased isolation

Increased isolation

![]() Low employee commitment

Low employee commitment

![]() Growing disposability

Growing disposability

![]() Greater hostility and enmity

Greater hostility and enmity

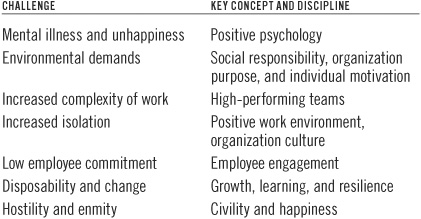

Second, a number of key concepts and even entire disciplines have arisen in response to—or at least of relevance to—these challenges. (See Figure 2.1.) The concepts we think are especially relevant to the preceding challenges are in the second column:

FIGURE 2.1 Overview of Fields and Disciplines Contributing to the Concept of Abundance

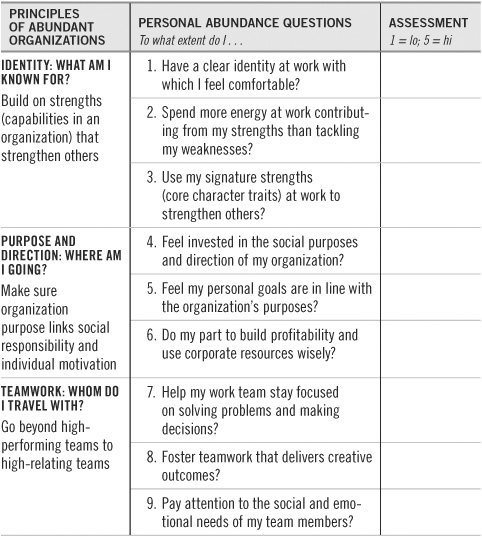

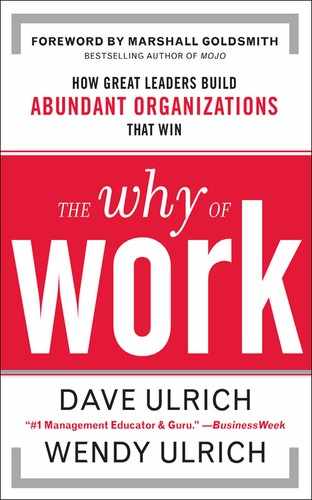

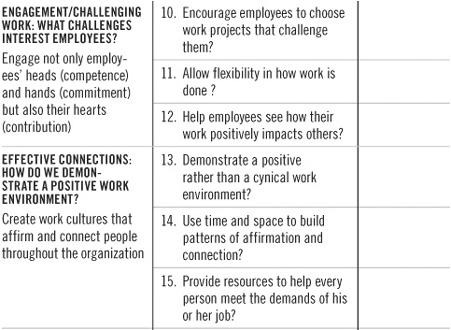

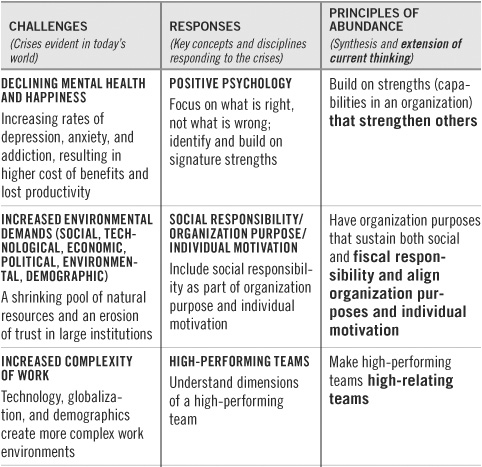

Our intent with the concept of abundant organizations is to both synthesize and complement insights and research around these key concepts, adding ideas that take each approach another step and focus it on leaders within an organizational setting. The questions and ideas that follow emerge from this synthesis. (See Table 2.1.) We provide an overview of these questions here, and the remaining chapters will probe these questions in greater detail. (See endnotes for more on the theories that provide answers to each question.)

Seven Questions That Drive Abundance

We propose seven questions to help leaders drive the abundance agenda—questions that help leaders make meaning, add value, create emotional energy, and foster hope while at work. These questions apply to leaders at the personal level (Am I finding abundance myself?), at the interpersonal level (Do we have an abundant work team?), at the organization level (Are we fostering abundance in this organization?), and at the societal level (Can our industry or community help humanity at large?). The key concepts listed on the right in the preceding list help us approach these questions. The key principles of an abundant organization emerge from these approaches. This is the architecture for abundance.

1. What Am I Known For? (Identity)

A sense of abundance is fostered by a clear sense of who we are, what we believe in, and what we are good at. In the bank example, McKell and his team were excited when they shaped their organization’s future identity around efficiency, trust, and citizenship. They then had to turn this corporate identity or brand into personal action among the 30,000-plus bank employees.

Chapter 3 describes how leaders can shape an organ ization-wide identity and then help individuals use their personal strengths to foster that identity and succeed at work. It also describes how leaders shape organizational strengths (capabilities) to build an abundant corporate identity or brand, turning external stakeholder expectations into internal corporate actions.

The field of positive psychology helps leaders answer this primary question. The traditional approach of psychology to depression, anxiety, and addiction disorders has been to develop models and techniques for fixing what is wrong with us. Few theorists or clinicians also probed what is right. Into this space, Martin Seligman and his associates have inserted the proposal that the domain of psychology extends beyond fixing pathology to probing health and happiness.1 Positive psychology asks what makes people happy in the long run. Researchers in positive psychology have discovered that when we identify and regularly use our signature character strengths, life becomes more satisfying and meaningful.2 They further assert that even when we must cope with depression, anxiety, addiction, or other mental illness (and their corporate equivalents), building on our signature strengths fosters creativity and courage for tackling our challenges.

The abundant organization adapts principles of positive psychology to help leaders build both organizational strengths and the strengths of individual employees.3 In addition, we propose that leaders in abundant organizations not only recognize and build on strengths but also use those strengths to create value for external stakeholders. At both personal and organizational levels, the meaning we find from our strengths deepens as we not only build on our strengths but build on strengths that strengthen others too.

PRINCIPLE 1

Abundant organizations build on strengths (capabilities in an organization) that strengthen others.

2. Where Am I Going? (Purpose and Motivation)

Abundance emerges from a clear sense of what we are trying to accomplish and why. Too often employees’ and employers’ goals are at cross-purposes, resulting in both individual frustration and organizational underperformance due to employee cynicism and lack of perceived corporate vision. As McKell and his team worked through the paradoxical goals of trust, efficiency, and citizenship, they created a sense of corporate purpose that helped employees fulfill their personal purposes through their work at the bank. Employees who can meet their personal goals at work remain motivated and engaged; those who can’t, go in a different direction, physically or emotionally.

Chapter 4 offers suggestions for how leaders create purposeful organizations that help employees’ personal ambitions match organizational goals. When our personal goals align with the organization’s goals, work feels like a meaningful extension of our private journey. As we both own and personalize our company’s mission, we find opportunities to impact broad societal problems we care about.

Social responsibility and environmental activism are fields that speak to the importance of addressing society’s biggest problems while investing in corporate citizenship. To manage scarce resources and rebuild organization reputations, many leaders have begun to pay attention to a “triple bottom line” of people (values and reputation), profits (financial return), and planet (e.g., carbon footprint).4 Environmental activists help corporations audit their carbon footprints and reduce energy consumption. Other organizations demonstrate a caring heart as they invest in philanthropic initiatives. These citizenship efforts underscore values of stewardship and accountability that help employees see how their personal values align with corporate values to make a real difference in the real world.

Just as the bank had to balance profit, purpose, and people, leaders in the abundant organization focus on sustainable profit as well as environmental sustainability. An organization that emphasizes social contribution without facing the economic realities of creating value for customers and investors will not survive. While bankruptcy will certainly reduce an organization’s carbon footprint, it will also eliminate its ability to employ workers, make useful products, offer customers innovative solutions, and build communities.

PRINCIPLE 2

Abundant organizations have purposes that sustain both social and fiscal responsibility and align individual motivation.

3. Whom Do I Travel With? (Relationships and Teamwork [Th]at Work)

Our sense of abundance is enhanced by meaningful relationships. The increasing complexities of today’s workplaces require combining people with different skills into cohesive and high-performing teams. As McKell and his team worked to shape the bank’s direction, they found that their ability to work as a team turned individual strengths into organization capabilities. When they put aside individual biases for the good of the overall bank, they made the whole of the team more than the sum of the individual players. They worked to create this sense of teamwork throughout the organization.

Chapter 5 suggests specific ways leaders can strengthen positive work relationships that enhance teamwork. These work relationships make even difficult work more doable. Our meaningful work relationships include friendships, mentoring relationships, and professional networks.5 Research on high-performing teams explores the ways teams coordinate the efforts of many people to solve complex problems. Although teamwork is itself more complicated than working alone, it also allows team members to reduce complexity by specializing. Research suggests that high-performing teams operate with clear purposes, good governance, positive team member relationships, and the ability to learn.6

While leaders must attend to teamwork in complex work settings, the concept of abundant organizations goes beyond teams that produce and perform their tasks well to teams that engender a kind of passion that allows for creativity, focused energy, trusting connections, and mutual respect. High-performing teams come from high-relating people. Research on successful marriages suggests patterns and stages of effective long-term committed relationships that can be applied to teams in organization settings. The best teams work through these stages and use these patterns to combat “organization divorce” characterized by burnout, turnover, and lost productivity. When leaders help their organization “families” move beyond the superficialities of getting along to struggling through conflict so that they can understand one another’s strengths and weaknesses, they can approach the kind of synergy that occurs in the best of human relationships. They gain a competitive advantage over a less relationally sophisticated competitor. This means that leaders need to learn and model the skills of building good relationships at work. Lynda Gratton has captured this sense of team cohesiveness with the term glow, which includes a cooperative mind-set, jumping across boundaries, and igniting latent energy.7

PRINCIPLE 3

Abundant organizations take work relationships beyond high-performing teams to high-relating teams.

4. How Do I Build a Positive Work Environment? (Effective Work Culture or Setting)

Abundance thrives on positive routines that help ground us in what matters most. While bad habits thrive on isolation and shame, positive routines help us connect with ourselves and others. As McKell and his team focused on their future identity, they wanted to establish a culture focused on building what is right, not just eliminating what is wrong. They wanted to replace backbiting with forward thinking, politics with collaboration, and self-interest with other-directed service.

Chapter 6 suggests ways leaders can create and sustain positive routines to foster effectiveness, efficiency, and meaningful connection. Leaders can tolerate cynical, negative, and demeaning cultures, or they can encourage constructive, affirming, and uplifting cultures. Leaders shape these cultures through their words and deeds. These cultures replace individual isolation with corporate connection.

Leaders who engender positive work environments promote good communication, development opportunities, and pleasant physical facilities to ensure a positive culture at work. Instead of building routines and patterns that encourage self-reflection, honest sharing, and the kind of consistency that brings people together, many of us build habits, addictions, and compulsive patterns that serve primarily to block out other people. Or we build almost no routines at all, leaving us untethered in time and space and making us unpredictable to those who want to connect. Routines and patterns driven by our deepest values help us stay grounded in what matters most and available to those who matter most. When leaders support individual and policy-level routines that help work work, they create a positive environment that both sustains productivity and fosters connection.8

Workplaces of all kinds use checklists and routines to ensure quality control. Checklists and routines that are chosen personally around core values and relationships lend predictability and stability to our lives. Instead of constantly fighting against time and space, we work with them in a mindful, realistic way. Whether personally or organizationally, flexible but consistent routines can help us know ourselves and others while countering both the perfectionism and the unpredictability that get in the way of connection.

Abundant organizations create positive work environments that affirm and connect people throughout the organization.

5. What Challenges Interest Me? (Personalized Contributions)

It is hard to imagine abundance in the absence of challenge. The most engaged employees are generally those whose work gives them the opportunity to stretch while doing work they love and solving problems they care about. The bank executives gave employees a new challenge when they shifted the focus from turnaround to transformation through efficiency, trust, and citizenship. These three pillars of the bank’s identity challenged employees to solve problems they cared about.

As leaders involve both teams and individuals in enjoyable challenges, they engage employees’ hearts and their minds, as Chapter 7 discusses. Different people find different kinds of work easy, energizing, and enjoyable and different problems meaningful. Leaders need to adapt broad general challenges to individual requirements and predispositions.

The study of talent has evolved from a focus on employee competence (ability to do the work) to employee commitment (willingness to do the work).9 Employees who are competent but not committed will not perform to their full potential. Commitment comes from building an employee value proposition that engages employees to use their discretionary energy to pursue organization goals.10 Commitment or engagement grows when we work in a company with a vision, have opportunities to learn and grow, do work that has an impact, receive fair pay for work done, work with people we like working with, and enjoy flexibility in the terms and conditions of work.

Leaders in abundant organizations take employee competence and commitment another step—to employee contribution. Contribution focuses not just on activity but on the meaningfulness of the activity. For example, a teenager may be highly competent at video games (he wins them often), have a high commitment to video games (shown by playing them for hours at a time), but still not find real purpose and meaning in game playing. An employee may be competent (able to do the work) and committed (willing to work hard), but not have the sense of abundance that comes from also making a contribution to a greater good.

PRINCIPLE 5

Abundance occurs when companies can engage not only employees’ skills (competence) and loyalty (commitment) but also their values (contribution).

6. How Do I Respond to Disposability and Change? (Growth, Learning, and Resilience)

Abundance acknowledges that failure can be a powerful impetus to growth and learning. When we face change and take risks to work outside our comfort zone, resist defensiveness about mistakes, learn from failure, and keep trying, we become not only more resilient but also more satisfied with life. McKell and his team knew that as they tried to implement their new organization identity and purpose they would make mistakes. Instead of hiding from and finding someone to blame for mistakes, they committed to facing and learning from them.

Chapter 8 reviews how leaders can encourage learning and resilience. Abundance is less about getting things right and more about moving in the right direction. Resilience reflects a positive outlook on work and shapes learning for the future rather than lamenting the past.11

Research on personal resilience and learning organizations offers exciting insights into what helps people and institutions endure in the face of both suffering and setbacks. By studying what helps POWs survive and thrive, how Navy Seals can be trained to stay calm under attack, and what abused children who become successful have in common, we get hints about how leaders encourage learning under conditions of stress and challenge.

Unlike the assumption of disposability that governs so much of modern society, resilience and learning principles challenge us to “repair, reuse, and recycle” people, products, and programs rather than tossing them. In tough economic environments organizations will necessarily reduce staff, drop products, and cut nonessential programs; nevertheless, hiring freezes and reduced funds for research and development also mean we must work with whom and what we have. Abundance means we not only learn attitudes of resilience that help us thrive under stress; we also use these principles to make do with what we have. As we do so we come to realize that what we have is actually enough.

PRINCIPLE 6

Abundant organizations use principles of growth, learning, and resilience to respond to change.

7. What Delights Me? (Civility and Happiness)

Abundance thrives on simple pleasures. Sources of delight might include laughing at ourselves, appreciating excellence, relishing beauty, being present in the moment, and having fun at work.12 As McKell and his team laid out the bank’s new identity, they encouraged employees to have fun in shaping this identity. Corporate fun included contests, celebrations, and communications about the new direction.

When leaders encourage civility and delight in how work is done, they go a long way toward creating a sense of abundance, as shown in Chapter 9. These sources of delight are highly personal, depending on the personality of the leader and the requirements of the employees.

The hostility rampant in modern life is itself under fire these days. The cry for tolerance demands that we outgrow our racial, religious, political, ethnic, and gender stereotypes. The cry for civility also calls on us to outgrow our we-they, win-lose, right-wrong, blame-and-shame mentality. As we move away from hostility and blame toward problem solving, listening, curiosity, and compassion, simple civility greases the skids.

Under the rubric of valuing differences, leaders are encouraged to understand, respect, and learn from the perspectives of people of different races, genders, backgrounds, or even professional training, replacing hostility with civility. We may also want to look for and rejoice in the different ways people find sweetness in life, going beyond civility to delight. Sensitivity to such differences helps us find a wide variety of ways to bring pleasure and delight into the work-place. For some perhaps a celebration of 10 years of service is meaningful; for others a renewing sense of delight is evoked by a note from the boss, a compliment, a shared joke, a favorite song, a different chair, a new dish at lunch, or simply a beautiful sunset shared on the way to the parking lot. Delight often comes in small packages, and when money is tight it helps to know that small and simple pleasures spread over time have more impact on our sense of well-being than grand one-time gestures.13

PRINCIPLE 7

Abundant organizations attend not only to outward demographic diversity but also to the diversity of what makes individuals feel happy, cared for, and excited about life.

Organizational Application

Much of what brings meaning into our personal and professional lives can be categorized under the preceding seven headings. When leaders help employees explore these questions, they help create abundant organizations with positive individual and organization results:

![]() Higher commitment, better employee health, improved productivity and retention14

Higher commitment, better employee health, improved productivity and retention14

![]() A leadership brand that builds investor confidence15

A leadership brand that builds investor confidence15

![]() Increased customer commitment (because customer attitudes about an organization correlate with the attitudes of its employees)

Increased customer commitment (because customer attitudes about an organization correlate with the attitudes of its employees)

![]() Increased investor confidence in future earnings and higher market value (based on intangible assets like leadership and quality of employees)

Increased investor confidence in future earnings and higher market value (based on intangible assets like leadership and quality of employees)

![]() Improved community reputation, merited by stronger social responsibility.

Improved community reputation, merited by stronger social responsibility.

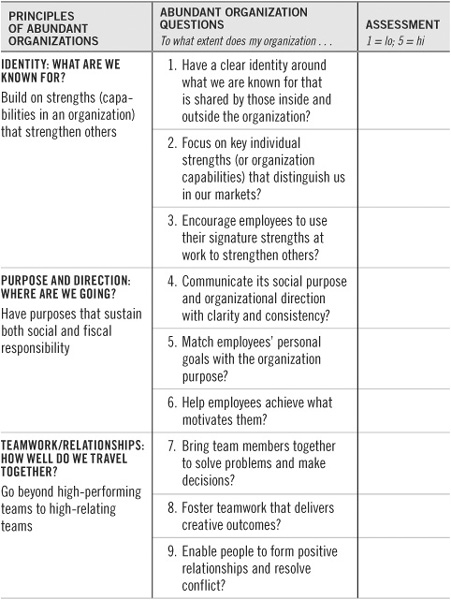

Table 2.2 provides an organizational assessment tool for abundance to help leaders parse out the components of abundant organizations and assess areas of strength and weakness. The remaining chapters of this book will address each area in more detail. These chapters will give leaders specific tools and concepts for increasing organizational abundance in teams, divisions, or companies.

TABLE 2.2 Assessment of the Abundant Organization

Think of the organization where you work as you complete the following assessment. In a small company, this would be the entire organization; in a large company, it would be a division, plant, geography, or other work unit.

These principles apply at a personal level as well, as shown in Table 2.3. Questions on this individual assessment tool can help you and individuals you work with gauge your sense of personal abundance and meaning at work. You will find more specific tools and concepts for increasing your personal sense of abundance at work in the chapters that follow.

Getting high scores on these questions does not mean that work will suddenly feel easy, people will get along instantly, customers will flock to buy products, or stock prices will soar overnight. Meaning does not ensure ease; it offers hope. Playwright and founding president of the Czech Republic, Václav Havel, writes, “Hope is not prognostication . . . It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.” Abundance emerges from the growing conviction that what we are about “makes sense”—that it contributes to something larger than ourselves and that it is grounded in our deepest values. Such conviction does not forestall all problems, but it helps us confront problems with courage and integrity. And it is in that confrontation that meaning—abundance—flourishes.

In economically good times, abundant organizations matter. In tough times, they matter even more. When organizations address the key questions and build on the guiding principles of abundance, capable, committed employees also have the satisfaction of knowing their work makes a genuine contribution. Customers receive products and services that meet their needs. Investors have more confidence in the company’s future. Communities and ecologies are sustained responsibly.

In short, there is enough. And to spare.

TABLE 2.3 Assessment of Individual Abundance at Work

Think about your current personal experience with work as you complete the following assessment.