CHAPTER 3

Manage Yourself

One of my favorite quotes is from that famous philosopher Winnie the Pooh, who once said, “This is far too important to be taken seriously.” Perspective is critical when developing others, and we need to be aware of our own inner world, our thoughts, our beliefs, and our impulse to react to external forces and events. Sometimes we want something so badly for the other person that we become evangelical about it and turn the person off. At other times our frustration may interfere with what we say and how we say it. To engage another person in becoming more self-aware and responsible, in other words to engage that person’s Third Factor, we have to create an environment where this can and will occur. The manager’s or coach’s ability to self-manage is significant, because he or she is the most influential factor in the performer’s world.

To develop others you must be awake and aware. It is challenging, if not impossible, for a coach to trigger the Third Factor in someone if the coach is lost in the emotional soup of the moment or caught up in some perceived injustice from earlier in the morning. Historically speaking, there was no one better at being “awake” than Buddha. He may have been the ultimate self-manager and Igniter!

After his enlightenment, a traveler asked Buddha, “What are you? Are you a man?”

“No,” was Buddha’s reply.

“Are you a god then?”

“No,” answered Buddha.

“Then you must be a ghost,” said the questioner.

“No,” answered Buddha.

“Then what are you?” demanded the man.

“I am awake,” was Buddha’s reply.

This chapter is about waking up and starting to notice how little we actively direct what we do, how often we are at the mercy of what we are experiencing or what our beliefs are.

Knowing yourself is certainly part of managing yourself, but alone it is not enough. And awareness often leads to a change in behavior, but not always. For example, someone could know that he or she is behaving like a complete jerk and yet do nothing to change his or her ways. Regardless, awareness is the first step. If, for example, I ask you to become aware of your jaw muscles and to notice any tension there, you will probably relax the muscles. I don’t have to stop and teach you how to do that. Once you have become aware of the tension, relaxing is to some degree automatic. But this is not true for all behavior, especially in the context of trying to develop another person.

Depending on your background, you may step on any number of landmines as you venture out into the developmental field. Some of them will be connected to your beliefs; others will be connected to your tendency to react to things you see or hear. These may make it difficult to access your developmental bias when it is most needed. What will become obvious is that these feelings, opinions, and reactions are not going to go away just because you notice them. You have to become conscious of them to the point where you’re prepared to take action to manage what you’ve uncovered. Only in that way will you move to “conscious competence.” If you become extraordinarily good at noticing and then acting to deal with what you notice, you may eventually move into the realm of unconscious competence, or automatic expertise. But that isn’t easily achieved. Even Mahatma Gandhi had to work hard and persistently at self-management.

The term self-management is somewhat misleading. It might be more accurate to talk about management occurring from the position of the Self. What is unique about us as human beings is that we have the capacity to be aware and to self-direct. I find it helpful to think about that capacity as coming from the Self, which could also be called the Observer. The Self notices what is happening and what we are experiencing, and steps in and redirects us to where we need to be. In the third section of this chapter we talk directly about the role of the Self.

If you are a parent, think about those times when you aren’t at your best in dealing with one of your children. In the middle of an ineffective rant, have you ever noticed a voice inside you whispering something like, “I can’t believe I’m actually saying this”? Who is speaking there? It’s the Self, the Observer, or, as Italian psychologist Roberto Assagioli put it, the Fair Witness. We all have this Self within us, and being able to access it, especially when under pressure, is critical if we are to be truly effective in developing others.

Here’s a story illustrating how I learned this lesson—the hard way! I have always had a strong developmental bias and have derived a great deal of pleasure from working with and developing others. I went into teaching for those reasons, although I certainly wasn’t all that good at it in the beginning. Early on I was much more focused on skills development related to the sport I was coaching than on igniting the Third Factor in the people I was coaching. Also, being fairly (some would say very) high-strung, I didn’t deal well with competition. It brought out the worst in me.

In 1968 I was hired as a physical education teacher for a new regional high school in Shawville, Quebec. I had had exceptional training in teaching and coaching from a number of people at the University of New Brunswick, particularly John Meagher, who to this day remains the single best instructor I ever had. We were taught the skills and then how to teach them—everything from how to demonstrate, where to stand in relation to the class, which way the class should be facing (e.g., back to the sun, boys’ class away from the girls’ class), to key teaching points such as progression and whole/part learning.

In our Friday afternoon coaching classes we learned not only from the varsity coaches at the university but from numerous guest instructors who coached the teams that played against UNB on Friday nights. As the university was close to the border, these included American as well as Canadian coaches.

I knew what to do and I’d been taught how to do it, but something interesting happened when games got tight and my competitive nature reared its ugly head. I reverted to coaching the way I had been coached back in the community in which I grew up. Every parent will immediately recognize this. We may read any number of books on parenting, but in a crisis it’s astounding how often our mother’s or father’s voice jumps out of our mouth!

I was reminded of my early coaching days a few years ago when I was presenting to a group of executives. At the break a gentleman approached me and asked if I recognized him. I had to admit I did not, though the name on his name tag was familiar. It turned out I had taught him in high school. On the second day of the seminar he brought along a yearbook from the high school in Shawville containing three photographs of me that were embarrassing to look back on!

In the first one, I am in the middle of the floor at a basketball game speaking animatedly to the referee. (I should point out to non–sports fans that one does not coach from the middle of the floor in basketball.) In the second one I am being assisted off the floor by the principal and a fellow teacher. In the third, I am being escorted down the hall and out of the building. Being thrown out of the game, the gym, and the school was not a high point in my coaching career, but it certainly was a wake-up call.

Now, if you had asked my players how they felt about me as a coach, they would have spoken positively. Most of the time I had a wonderful relationship with them. Unfortunately, I did not perform so well in the competitive framework. It took me a few years to transfer the coaching skills I had been taught to the high-pressure environment of the performance arena. I was not yet a developer of people; I was still simply a basketball coach. I didn’t yet have a true, fully formed developmental bias. One of the key things I was missing was the ability to manage myself under pressure. This inability to self-manage was directly connected to my inability to access my skills and to get in touch with my purpose—what I was really there to do, which was develop the players—when I was under pressure. I was certainly not yet an Igniter!

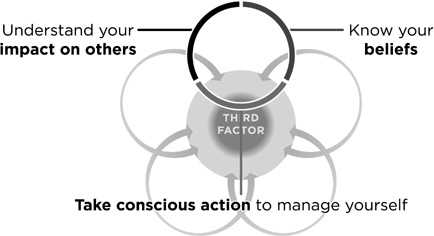

This failure to self-manage can also be observed in the workplace. We may display excellent managerial and developmental skills when things are running smoothly. But how we perform when the deadline changes, a key performer is on holiday or off sick, and a senior executive needs something yesterday is the true measure of our leadership and developmental skills. Coaches who can manage themselves understand the impact they have on others, are thoroughly attuned to their own beliefs and aware of how these affect their behavior, and take conscious action to ensure they are managing themselves at all times.

To ensure that everything we cover from here on is applicable to your world, I will use meetings and the leading and facilitating of meetings as an example in each chapter. As a leader you spend a lot of time in meetings of one type or another, and how you act in those situations reveals a lot about your beliefs and philosophy, your self-management skills, and your ability to communicate. Meetings are also a great forum in which to display your developmental bias. As we’ll soon see, there is much you can do of a coaching nature in these sessions.

Understand Your Impact on Others

One of the primary reasons coaches need to understand and manage themselves is that they have a dramatic impact on those around them. Of all the things in the performers’ environment, there is none so important as the coach. If the performers are spending time adjusting and adapting to the coach for whatever reason—the coach is moody, an ineffective communicator, or not a good listener—it will be very difficult for them to move to high performance. People cannot spend time adjusting to the idiosyncrasies or lack of skill of their leaders and still be exceptional performers. If your people are spending 10 to 15 percent of their time adjusting to you and the distress you create for them, they are unlikely to perform at their highest level.

As coach John Wooden once remarked, “Manage yourself, so others won’t have to.”

In a workshop I did with some of the top developers of people in the country (forty Olympic coaches), I divided the participants into four groups, each with a different time frame: three months, three weeks, three days, and three hours before their athletes compete at the Olympics. I asked them to break down, for each of those time frames, how much time was spent on encouraging competence (making the athletes better) versus confidence (making the athletes believe they can succeed). There was 100 percent agreement that confidence was the most important factor in all phases—and that it became increasingly important as the coaches moved from three months to three hours before the competition.

I then asked them, “How many of you are perfectionists?” Lots of hands went up. So I asked, “What is your natural tendency as the pressure builds before the event? To become more perfectionistic, or less?” They could see where this was going but acknowledged that they would tend to be more perfectionistic. But what did their athletes need? Less, much less. Most coaches are very good at detecting and correcting errors, an important ability. But without awareness, sometimes under pressure our greatest strength becomes our biggest weakness because we let our tendencies dictate our behavior. We forget to manage ourselves.

Because it’s so hard for people to excel if they are spending time adjusting to the coach and/or the stress the coach is creating for them, many of the coaches told me that they made a point of sitting down with their athletes and saying, “Tell me if there are things I do that irritate you,” or, in the words of coach Debbie Muir, “drive you crazy.”

A few years ago I was working with a media company at a resort north of Montreal. I was having lunch with two women who reported to a senior VP, and we were speaking French—or, more accurately, they were speaking French and I was listening. My French is not strong, but I get by. I speak what is called street French. It improves with beer—at least I think it improves with beer. There was no beer at that lunch. They were in the middle of talking about their boss when the conversation abruptly shifted to the weather and they laughed. I had obviously missed something, so I stopped them and said, in French, “I’m lost.”

“Where did we lose you?” they asked in their flawless English.

“When you shifted from your boss to the weather and then started laughing,” I replied.

“Oh,” they said. “It’s the same thing. You see, our boss is very moody, so if we have to see him we phone his secretary first and ask, ‘What’s the weather like today?’ And if it’s stormy and we don’t really need to see him or it can wait, then we don’t go.”

The anecdote was funny, but is it really funny that these two competent women have to spend time and effort adjusting to this turkey? I think not. How can you expect people to move to high performance if they are spending 10 to 15 percent of their time adjusting to you? You may not be negative or dictatorial like this man, but perhaps you lack clarity, are unwilling to confront, or have some other blind spot that requires others to adapt, wasting valuable time and energy that could be better spent moving into higher performance. This man was clearly a better Extinguisher than an Igniter. He effectively put out any inner fire of the Third Factor in those under his leadership.

A few years ago, when I was doing a workshop with a team from a major electronics firm, we investigated some of the self-management skills that would help people perform better. The team decided to role-play a situation with the senior manager and one of the people who reported to him. The manager had his “mental preparation” plan, as did the employee. The manager told me his goal was to put the employee at ease and to create a relaxed atmosphere. One of the things he did while casually talking to the employee was to pick up a baseball he kept on his desk and toss it up and down in his hand, with his feet up on the corner of his desk.

In the debriefing session, both parties talked about their strategy. To a person, everyone in the room who reported to the senior manager said they hated the baseball toss. Some talked about it as a distraction, some as an indication of indifference, some as a symptom of lack of caring—the complete opposite of the boss’s intention. If something this small has an impact, imagine the large, negative impact of a moody boss or one who lacks the ability to provide clarity on performance expectations!

Managing the impulse to react is a big part of leading. This is critical in confronting, as we will see. It’s also important on a day-to-day basis or before big events. Hockey coach Mel Davidson told me, “I really have to work on reaction, especially before a game because I’m so anal on the details and the channel of communication. I have to be very aware of my reactions—before and after a game—because I expect things to flow smoothly on game day and especially when we get to the rink and after. Sometimes I react more quickly and maybe more harshly than I should.”

She went on to point out that you don’t want to go to the opposite extreme of being too relaxed, because people may get the wrong message. “I’m also conscious of not being too light,” she said. “Your support staff in particular can read that as, ‘Oh, this game isn’t important’—especially in our situation, where we have games people anticipate we’ll win regardless. So I have to be really careful. Whatever mood I want to portray in the important games is the one I also have to portray in the games they perceive as ‘easier.’ Your staff reads your mood.”

Mel’s primary interaction with her players is during the game-day meeting, which lasts twenty to thirty minutes, and between periods. What about your meetings? As a leader are you aware of the impact you have on your “players,” and do you consciously manage the message you convey with your body language? Do you ensure that people feel free to express their opinions on key agenda items? Do you create a high-performance atmosphere where all are free to give their best? These are tough questions, but as we move forward through the material, the “how to” of it will become clearer. If you can become effective as a developmental coach in a meeting environment, you will have moved a long way toward being a really good leader.

Know Your Beliefs

At the turn of the century a man named Louis Wirth said that the single most important thing we need to know about ourselves is what we take for granted. What assumptions are we operating under that we never question and assume to be true? In his book The Path of Least Resistance, Robert Fritz reveals that the roads in what is today the city of Boston were actually designed by cattle choosing the path of least resistance as they moved across the terrain. Those cattle paths eventually became dirt roads, then gravel roads and finally paved roads. His point is this: The only way to change what is on the surface, the roads, is first to change the underlying structure, what is supporting those roads. If you don’t level out the hilly sections or fill in the valleys, the path of least resistance will be where it’s always been. So too with us. The only way to change what we do on the surface—our behaviors—is first to go inside and change the beliefs that support those behaviors. Unless we change our beliefs, we cannot change our behaviors.

Here are a couple of questions for you to ponder. What do you believe constitutes effective coaching? When you think of a coach, what images and thoughts come to mind? Without being aware of it, you may hold a picture of a coach as an expert; someone who takes charge and provides answers, direction, and a strong hand to those being coached. It is my hope that as you read this book, a picture of coaching will emerge that is more complete and “performer-centered.”

A woman in the executive development program at Queen’s University, while on a tour of the library, looked up the word coach. She came back with this definition: “a vehicle that takes people of value from where they are to where they need to go.” Clearly a definition of a more regal, old-fashioned kind of coach, but accurate nevertheless!

Debbie Muir told me about her evolution as a coach and how she became increasingly aware of a restricted set of beliefs she held about what she did. “I think back to when I first started coaching, and there weren’t a lot of role models out there for me,” she said. “I read an article, an interview with Don Talbot [an Australian swim coach], about how you just have to be the most hard-assed person in the whole world. Don’t compromise anything; you’ve got to be tough. He became my role model, and for the first three or four years of my coaching career I was like that.

“I remember one swimmer in particular. Her brother was getting married on a Saturday and she wanted to go to the rehearsal dinner the night before. She would have to miss a practice. I said, ‘No, you can’t go. If you want to be on this team you have to be at practice tomorrow.’ I was that sort of tough. For the wedding she was going to have to miss a practice, so I said, ‘I’ll let you go to the wedding, but now we are going to have our practice early in the morning so that nobody misses it.’ I was so rigid. You’re not going to get too far being like that. Eventually I figured it out, because it also wasn’t my personality.”

What you believe can dramatically restrict your ability to coach, even if your beliefs are based on past successes. In fact, there are occasions when nothing gets in the way of future performance like past success. When we believe we have the formula, many things can start to happen: effort level drops slightly, we close ourselves off to learning and information in the competitive environment, we become myopic. We need to keep in mind that continued success—in sport, in business, and in life—requires continual and ongoing adjustment to changing conditions.

Our beliefs determine our behavior, which in turn is tied to our performance. Therefore, a restrictive belief system leads to limited performance levels. In other words, you can’t achieve success if you don’t coach for success. You need to coach to the highest common denominator, believing that everyone wants to engage their Third Factor—all the while realizing that this doesn’t hold true for everyone all the time. Your philosophy is vital to your success as a coach. Any limiting belief (such as “people want to take the easy road”) can lead to coaching behavior that results in a self-fulfilling prophecy or narrows the possibilities.

Your Philosophy Is Your Touchstone

The John Woodens of this world have a clear set of deeply held beliefs that are grand and inclusive in nature. Anyone employing them will realize success. The beliefs are well grounded in an understanding of human behavior and fit all parties who wish to get better. There are many building blocks and levels in Wooden’s pyramid to success, all underpinned by a philosophy as full and diverse as the people he is coaching. Swen Nater, who played for Coach Wooden, talks about one aspect of this philosophy in his book You Haven’t Taught Until They Have Learned.

Coach is … a stickler for fairness. But that didn’t mean treating all his players and students exactly alike. In the 1930s, he came up with an approach he called “earned and deserved.” To quote Coach Wooden: “I believe that to be fair to all students, a teacher must give each individual student the treatment he earns and deserves. The most unfair thing to do is to treat them all the same.”

Swen points out that his coach didn’t just make that speech on the first day and then not follow through. Players who were late for practice, for example, but who had not only a good excuse but a record of punctuality, were allowed to practice, whereas others, whose past record wasn’t so good, were dealt with quite differently.

We all need to be more aware of how our beliefs might be limiting possibilities and be willing to open up to new or different belief systems. Listen carefully to any coach or business leader for a period of time and it’s easy to identify what he or she believes. Those with a strong developmental bias see possibility in everyone, ask lots of questions, and really involve the performer. Less secure coaches and leaders, with a high need for control, generally don’t have these tendencies. Expectation plays a huge role here. If you believe that everyone can succeed given the opportunity, your approach will be very different from that of someone who believes it’s how you dress or who you know that matters.

One of the things I notice in attending coaching clinics is that there are always lots of “developers” present. They never stop learning. They’re always in the process of “getting there,” never believing for a minute that they have arrived. Knowing that they always have more to learn is an important part of their belief system.

Your philosophy is your touchstone. It makes the world more black and white at challenging times. Let me explain. Kazimierz Dabrowski wrote on moral and emotional growth. He believed that when we are young we often see the world as black and white, but as we grow we become aware that there are actually many shades of gray. We struggle with what is right because often there is no clear answer. However, once we have established for ourselves a clear hierarchy of values, the world once again becomes more black and white.

Coaches I have been speaking about—from John Wooden to Andy Higgins—have a clear hierarchy of values. They have a firm set of beliefs concerning their role as developers of others, and their developmental bias is grounded in these beliefs. These coaches are not going to compromise their values simply to win a game, or look the other way when a key player is not adhering to team rules. They are not swayed by what is happening moment-to-moment but are guided by their philosophy, what they believe. More than a few cases in recent history—from steroids in sport to the lack of ethics in big business—indicate that we need more leaders who have the values of exceptional coaches.

Beliefs, Half-Truths, and Paradoxes

One of the problems with beliefs is that many consist of half-truths. Take a common belief like “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Is that true? It may be true if you’re busy and have many things to do, in which case you’ll want to focus on what most needs your attention, such as things that aren’t working well, or at all, rather than things that are okay. On the other hand, few of us drive to town in a horse and buggy. There was nothing wrong with the horse and buggy—it wasn’t broken—yet Henry Ford and others decided to “fix” it. As with many of our beliefs, this saying is true some of the time but not all of the time.

Often this creates a paradox: Winning is everything—and yet it isn’t. Decathlon coach Andy Higgins put it this way: “I consciously went to competitions reminding the athletes of this almost paradoxical thing of giving it the absolute best you can, but understanding that in the grand scheme of things it doesn’t mean very much. Running around [the track] till you can’t take another step and you’re right back where you started—what was the purpose of this? If they were keeping score or measuring, did they want to win? Yes! But the most conscious thing I did was to keep this thing in perspective and to understand that what really mattered in the end was what happened to the human beings, their growth, and their process. The real value is not medals but who they become in the process.”

James Autry, in his book Love and Profit: The Art of Caring Leadership, lays out his philosophy. He lists his principles on one side of the page and his corollaries on the other. One of his principles, for example, is “People will do a good job because they want to do a good job.” The corollary opposite this principle is “Not everyone wants to do a good job.” What is the truth? The truth is that both of these are true, and it is the ability to hold the “all of it” that is important. The world is not black and white and neither are the situations you deal with. Sometimes you have to have a belief in a philosophy that you know does not apply to everyone in all circumstances. Some people do not want to be developed—and they will need to be managed instead. But if you try to apply that to everyone, you will severely limit those who, given the chance, would thrive under the tutelage of someone with a developmental bias.

Your Beliefs Affect the Performance of Others

When I worked with one large international consulting firm developing their young leaders in the skills of coaching, I was interested to see the performance reviews and how greatly they varied depending on the nature of the supervision they received in the organizations in which they were placed. This particular consulting firm had what they called “fly-back Fridays” on the third Friday of every month, when the trainees would return to their home city and spend a day with the partner they reported to in the consulting organization. For the rest of the month they were in a matrixed organization where their direct supervisor came from the client organization in which they were consulting.

It was revealing to see how consistently even exemplary performers, who had been given exceptional performance appraisals on numerous previous assignments, received much more mediocre reports when they were placed under restrictive bosses. Clearly, they were fenced in and severely limited in achieving their full potential by the restrictive beliefs of these highly controlling leaders. I also noted that the levels of achievement for those organizations fell well below those in organizations where the consultants reported to leaders with a style more in tune with John Wooden’s “earned and deserved” approach.

Maximize Your Return on Investment

An understanding that not everyone is coachable also needs to be part of your belief system. Some people bring life issues into the workplace, and most managers are not skilled at dealing with those. This is why most organizations have an employee assistance program. When you see a behavior in someone reporting to you that is permanent, personal, and pervasive, unless you are a therapist you’re not going to be successful in developing that person. Likewise, if you are a parent and your child develops an eating disorder, you will need the assistance of a specialist. You and I do not possess the detailed maps required to give these individuals the kind of guidance they need to move forward.

As a coach you need to know where your time will be most effectively spent and get the best return for your investment. You need to work with people with whom you know you have a high probability of success. Research tells us, for example, that less than 3 percent of managers have ever turned someone who has been performing at a marginal level for years into a highly productive performer. Your most limited resource is time. So work with the steady, reliable performers, the top performers, and the new hires. The steady performers do most of the work and create very few problems, so they hardly ever get attention—at least individual attention. You ignore this group at your peril!

Many managers avoid coaching the top performers, sometimes because they are intimidated by them or feel the performers are already at their maximum. Nothing could be further from the truth. These people often have the biggest potential in terms of hitting the higher numbers.

The new hires need early successes and early wins, and that translates into at least an hour a day of coaching in their first few weeks and a minimum of thirty minutes thereafter until they are settled and on board. It’s amazing how many people have told me, “We do a thorough job of selecting and interviewing to get just the right candidates, and then when we bring them on board we ignore them or turn them over to marginal performers for training because we’re so busy.”

Take Conscious Action to Manage Yourself

In terms of focus, sport psychology differs dramatically from traditional psychology. (I discuss this in my first book, The Inside Edge.) Where traditional psychology, beginning with Freud, focused primarily on dysfunction, sport psychology, or what now might best be called performance psychology, has focused on uncovering what exceptional performers do on the inside—in their minds—that makes them perform so well.

If you are going to become mentally fit so that you can lead effectively under pressure, there are four areas you will want to work on: perspective, imagery, energy management, and focus. We have created a website (www.ignitingthethirdfactor.com) to assist you in learning to use these skills. Mental skills used by elite athletes and coaches to manage themselves require practice to become ingrained and therefore usable at challenging times. We will cover some skills here, but I encourage you to go to the website. Think of it as your mental gymnasium. Some of the skills, for example centering, are easier to practice with a voice leading you through them.

Sometimes by changing an external factor, such as the composition of your team or a meeting time, you can improve the environment for all concerned. But even when you cannot change external factors, you can still choose your reaction to them. Most of the time you are not reacting to what is happening but to the story you’re telling yourself about what happened. Reframing is about changing the story and acquiring the energy you and others need to persist. We cover reframing in detail in Chapter 7, “Embrace Adversity.”

I asked Debbie Muir what she did to manage herself.

“You know all the sport psychology stuff you do with athletes? Well, I did it all with myself. In the beginning it was just about learning things like the Jacobsen technique and how to relax, then the whole self-talk area and that kind of thing. It really evolved over the years to the point where I used imagery, imaging for myself how I was going to coach that day in training. Every day in the car on my way to the pool, I would imagine how I wanted to be that day and what I wanted my face to look like, how I wanted my voice to sound, and how I wanted the athletes to respond to me. It was one of the skills I used.”

Debbie was quick to point out that the impact of pressure doesn’t suddenly go away. That’s where humor and your relationship with your people can carry the day. “The athletes used to tease me because at every competition I’d get this bright red rash up my neck to my chin, so I started wearing turtlenecks and track suits. It was a sort of joke. They’d look to see if I had my rash and then say, ‘Oh, we’re okay, Debbie’s got her rash, we’d worry if you didn’t!’”

How important is this ability to self-manage in today’s high-paced work environment? From the studies on the impact of negative, out-of-control bosses on employee retention to research on burnout, there’s evidence that the boss’s ability to be human and aware and not act out feelings is critical.

The business world, like the world of competitive sports, can be a pressure cooker. Competition can bring out the worst in anyone. Good coaches are aware coaches, and aware coaches are those who continually strive to be better. Managers need to be able to manage not just their performers, but more important, themselves: their expectations, their personal tendencies, their arousal level—all of which directly impact their ability to read the situation, make good decisions, communicate clearly and effectively, and react appropriately.

Ironically, leaders choke as often as their performers. Success comes down to learning to manage what is happening on the inside, at the body, mind, and feeling level, in order to perform better outside, in the office or sporting venue. Let’s bring this to life with a few anecdotes and then cover the basic skills needed to develop better self-control and manage others more effectively.

Prior to the Torino Winter Olympics of 2006 I was presenting to a group of potential Olympic medalists and their coaches. I asked them how important physical fitness was for them at the Games. They said, of course, that it was incredibly important. I asked them how much time, on a weekly basis, they devoted to physical fitness. They all indicated that they spent many hours staying physically fit. Then I asked them, “What percentage of your performance at an Olympics is mental? How important is it to be mentally fit?” The percentages on the perceived value of psychological skills ranged from 80 to 100 percent. But when I asked them how many hours a week they actually worked on being mentally fit, the answers revealed that the majority did very little.

I am always amazed by these revelations. If you rate something as vitally important, why wouldn’t you work on it? But, as we will see in the next paragraph, it’s true not just for athletes. One primary reason for inaction is time, and a second is clarity. It is easy to imagine and therefore be able to complete physical tasks, but not so easy to imagine or complete mental tasks. My book The Inside Edge assisted people in applying key mental skills to the business world. These mental skills are critical if you wish not only to manage yourself but to move yourself internally to a place where you can enhance your own performance.

Raise Your Awareness—Then Act on It!

I once asked a group of business leaders how important self-control and self-management was for them. To a person they said it was vital that as leaders they be able not only to manage themselves but to appear strong and confident on the outside, especially in crisis situations—which, they pointed out, occur all the time in the current work climate. I asked them how many articles they had read, tapes they had listened to, or seminars they had attended in the past six months to assist them in dealing with this challenge. Their answer, as a group, was a resounding silence as they looked around hoping someone else—anyone else—would answer.

Isn’t it amazing that so few of us will make changes based on information? It requires a giant wake-up call before we will act to change things we know we should change or learn things we know we should learn. I really encourage you to work on the self-management skills in this section. They are life skills—and the sooner you use them the better all aspects of your life will become. Don’t wait until you suddenly find yourself in a hospital bed to acquire this conviction.

Decathlon coach Andy Higgins had this to say about the need for awareness and self-management: “The better I knew myself, instead of acting out of habit, the better I became as a coach.” He went on to talk about learning what he needed to do.

“The first recollection I have of this awareness was in coaching high school basketball and yelling at the ref … and being extrinsically motivated because that’s all that mattered, despite the fact that I knew better. I would, on occasion, act like a goof, so my first conscious act was to speak to myself before a game about what I had to do—about what external actions I had to take. The first thing I had to do was sit on the bench, observe the game, and try to be useful and model the behavior I wanted. Anything like that requires such focus and will, because every so often I’d lose it.”

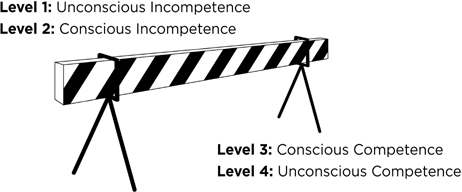

The first thing I teach in this area, which I call Mental Fitness, is the skill of active awareness. There are four levels of awareness in high performance, as you can see in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Four levels of awareness.

The first level, unconscious incompetence, is a total lack of awareness and action. Years ago we were unaware of a lot of things—such as the impact of asbestos on personal health. We were unconsciously incompetent—that is, we didn’t know any better. The same is true of our coaching. There may be actions we are performing now that are not good for the people we are developing, but until we know what these are, we really can’t do anything about them.

The second level, conscious incompetence, represents awareness without action. We know what needs to be done but we don’t do anything about it. We know we should exercise more, but … We know we should give better feedback, but … We know we should be more patient, ask more questions, floss more frequently, learn to relax—but, but, but.

There is a barrier between the second level, conscious incompetence, and the third, conscious competence, and the only way over that barrier is to act. “To know and not to do,” said Chinese philosopher Lao-Tse, “is not to know.” Knowing and understanding are not sufficient. We need to act.

At the third level, conscious competence, we become aware—and we act. When we are practicing and acquiring skills, such as the questioning, listening, and feedback skills outlined in the previous chapter, we need to pay close attention to what we are doing and how we are doing it. I’ve mentioned that great coaches are highly disciplined, and a good deal of that discipline is directed toward monitoring, modifying, and adjusting how they communicate with the people they are developing.

The fourth level, unconscious competence, is about automatic expertise. There are literally thousands of tasks you perform at this level—from brushing your teeth to driving your car. Sometimes even complex skills can get to this level—but not every time, even in the best of performers. There are days when Tiger Woods, for example, is “in the zone” (as this state is often referred to in the press), when he stands over the ball and everything is automatic. But most of the time he has to be consciously competent, fully aware of what he is doing and making small adjustments.

There may come a day when you are so good at giving competent, relevant feedback, for example, that it just flows out of your mouth correctly. But it likely will take thousands of consciously competent repetitions to get to that stage, and even then, the odd situation will require conscious adjustment.

Often people expect that certain activities, such as dealing with others, will get a lot easier over time. This is not necessarily the case. Choosing to take on the responsibility of triggering the Third Factor in another human being is choosing to take on a complex and full mandate that may never feel any easier. But eventually—and this is very, very important—you become better at it and find it much more fulfilling.

The third level, conscious competence, where attentive practice is active, is the level we occupy most frequently when we are performing at our best. This requires that we learn the skill of active awareness.

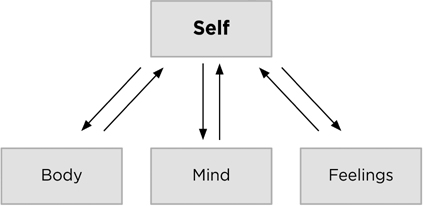

Body, Mind, and Feelings

Active awareness is a practical skill, not an intellectual experience. It is something you do, not something you know. The good news is that if you’re alive, then you’ve experienced active awareness. Let’s begin by taking a look at a simple configuration Roberto Assagioli developed to explain the key role of the observer within (see Figure 3-2). Much of the thinking in this section is drawn from his lifetime of work in a discipline he called “psychosynthesis.”

As human beings, and unlike most of our animal counterparts, we have the ability to observe ourselves—all of who we are and what is happening to us. By that I mean you can observe what is happening in your physical body—your breathing, any tension you may be holding, your heart rate, how rested or tired your body is, your tone of voice, and so on. You can observe things like what you’re thinking, what your mind is paying attention to, how your thoughts change, and how focused you are. You can also observe how you’re feeling. Are you anxious? Excited? Happy? Sad? Lonely? Competitive? Angry? You can move to a place where you are able to observe your body, mind, and feelings.

Your body, mind, and feelings are the means through which you interact with the world. They are your personality—both what the world observes about you and the means through which you communicate who you are and how you want to connect. They are not, however, all of who you are. You are much more than these. This is something we frequently forget.

The body, mind, and feelings are incredibly sensitive radar. They stimulate, enrich, and educate us about the world and ourselves in relation to it. It is not unusual, however, for our minds to give us way more information than we really need or can assimilate. The mind sometimes becomes fascinated with an idea or event that isn’t relevant to our lives or won’t move us toward what we want to do. The mind may hold tenaciously to a belief system that is counterproductive for what we’re dealing with right now. Our feelings often give us information we don’t want to hear or don’t know how to handle. The body often wants to do things it shouldn’t or avoid doing things it should. This can result in a confusing jumble of sensations, images, and thoughts.

Most of us get very little direct guidance or coaching on how to manage all this input. Basically it comes down to what we learned from observing our parents (our first and most powerful teachers), other role models we have consciously or unconsciously chosen, such as teachers, coaches, older siblings, and society, and the norms or rules of conduct in the culture in which we grew up. Some of us have had great teachers; for others learning has been a dysfunctional nightmare. For most of us it’s adequate just to be functional, but that isn’t enough to allow us to achieve our dreams. It takes effort to develop consciousness about what kind of relationship you want to have with your body, mind, and feelings so that you can direct yourself to your desired level of performance.

The first thing you need to realize is that you are not your body, your mind, or your feelings. Although you’re getting messages from all three, all the time, they are not who you are. Your Self is who you are. One of the unique things about us as human beings is that we have been blessed with awareness. We have the capacity to step back and notice what we are experiencing, make a choice, and act on that choice. We do not have to be swayed by, or driven into reacting to, what we are experiencing. This can be a challenging concept to grasp.

It Takes a While to “Get It”

A few years ago I was doing a seminar for some Olympic coaches, one of whom was cross-country ski coach Marty Hall. I was presenting the aforementioned concept on body, mind, and feelings. Marty was struggling with my statement that he was not his mind. As the class ended he was still arguing with me, convinced that he and his mind were the same thing, indistinguishable. We went for a beer and continued the discussion late into the evening and finally went home with the argument still unresolved.

The next morning I walked into class prepared with a new way to present the concept. “Marty” I said, “let me try one more time. I think perhaps you’ll get it this time.”

“It’s okay, Peter,” he replied. “I got it. There’s no need for further explanation.”

“When did you get it?” I asked.

“At 2:30 this morning,” he said. “I was thinking about the concept as I got ready for bed, I was thinking about it as I got into bed, but do you think I could get my mind to shut up and stop thinking about it as I tried to fall asleep? I realized at that moment that I definitely was not my mind, because my mind would not listen to me and stop thinking so I could get to sleep.”

Marty got it. Marty got it at the deepest level. He truly understood that he was not his mind. This is such an important distinction for you as a coach. When you begin to recognize that what you are thinking, feeling, and experiencing at the body level is not who you are, but something that is happening to you, then you can move to a place where you are no longer being controlled by what you are feeling, thinking, or experiencing. You are in control.

If you don’t make an effort to notice what you’re experiencing, however, you’ll be dominated and controlled by it. Unless you have that awareness and act on it, you can be hijacked by what you are experiencing, as the following illustrates:

John, a sales executive with a medium-sized paper company in Atlanta, Georgia, was on a joint sales call with one of his top sales associates. The client had been screened and was considered a prime candidate to become a major client. John had spoken with the senior buyer at a Rotary Club meeting a week earlier, and the buyer had been keen to connect with John and the sales associate. He had given John every indication that the sale would be, in John’s words, virtually a “slam dunk.”

They were barely into the meeting when the senior buyer turned to John and said, “This is not what we spoke about. You’re wasting our time.” John was stunned. He said he tried to recover, but his feelings took over and he stumbled through his reply, cut off his sales associate, and directed all his comments at the buyer. The meeting went nowhere and ended poorly, and John and the associate left ten minutes later, stopping at a small bar to debrief the performance.

Within ten minutes, John told me, he could think of everything he should have said and done in the meeting. It isn’t that he suddenly got smarter. When we become what we are experiencing, we move into what is referred to as the “choker’s profile”; arousal level goes up, the focus of attention narrows, and we miss relevant information and literally become narrow-minded. John knew what to do but he couldn’t access his skills because, in the grip of his own emotions, he was reacting badly to the buyer’s comment. His associate commented that the other people in the meeting had also reacted to the buyer’s rudeness and were sympathetic to John, but his reaction was so overpowering that he didn’t notice and eventually lost them as allies.

I asked John to tell me what he experienced at each of the three levels: body, mind, and feelings. It was easy for him to recreate the scene. He said that at the body level, his face started to flush, he felt suddenly warm, his heart rate increased, and his breathing was shallow and quick. At the feeling level he was experiencing a mixture of frustration, uncertainty, and betrayal, as well as some panic and a touch of anger. At the mind level his thoughts raced between “I can’t believe this” to “I’ve got to calm down,” but when he searched for an idea his mind seemed blank.

What John needed were self-management skills he could apply in the moment to manage what he was experiencing internally so that he could perform externally. (The website associated with this chapter, www.ignitingthethirdfactor.com, is your mental training room to prepare for just such moments.) John needed to notice what was going on and then act on that information. He could have employed what we jokingly call the FART technique—First Ask for a Repeat of the Threat—using words such as, “What aspects of what we’re covering do you think are a waste of time?” This would have bought John time to calm down. He could have used a centering breathing technique to manage his arousal level. He could have changed the way he was speaking to himself, or reframed the buyer’s comment as a request for information (rather than a threat) and then dealt with it in a more effective manner. The point is that there are many things you can do to get back on course, but these, like all skills, have to be practiced.

When you do notice what is happening—frustration, increased heart rate, anger, negative self-talk—you can begin to self-manage by using learned skills to reduce, transform, or eliminate the feelings, thoughts, or body symptoms you are experiencing. Some skills are designed to help you adjust or modify your perspective (e.g., reframing or self-talk). Others are from the area of energy management (e.g., the centering breathing technique). Or we might use imagery to circumvent what we are experiencing. The point is that when we notice that something isn’t as it should be, we have choices about how to deal with it.

You Observing “You”

The first step in becoming actively aware is called disidentification, a term first coined by the Italian psychiatrist Roberto Assagioli. It refers to the capacity to step back and notice what is happening from the position of the Self, also known as the neutral observer or Fair Witness. This is critical in determining what is really happening. Somebody once said, “I don’t know who discovered water but I’m sure it wasn’t fish.” When you are in the middle of something, especially if that something is really important to you, it’s difficult to form an accurate picture of what is happening and then determine what needs to happen. You need to separate yourself and your desires, beliefs, and expectations from the mix and see reality.

The coaches I interviewed all have a tremendous capacity to step back at critical moments and see what needs to happen. They do this in evaluating performances, in evaluating themselves and their actions, and in evaluating new ideas or possibilities for their teams and athletes. This is not only about managing moment-to-moment situations but also about being able to see what is needed in the long term rather than getting caught up in tunnel vision due to, for example, past success (“I’ve always done it this way”).

We will see later that this ability to disengage, disidentify, and in an unbiased manner determine what is happening and what needs to happen is especially critical when a performer is blocked or dealing with adversity. Here we talk about being able to do this for yourself.

There are three steps in active awareness: disidentify, choose, and act. Notice what is going on, make a choice, and then act to support that choice. The actions are the psychological skills—reframing, self-talk, affirmation, centering (breathing techniques), imagery, and others—that are found in any good book on performance psychology. We include a short example at the end of this chapter.

Let’s return to our meeting example. An advantage of the meeting environment is that we can quite easily disengage and disidentify every so often and see what’s happening to us as a result of what is transpiring or has already transpired. These small gaps allow us to become aware and to make sure we are on our intended course, that we have not been hijacked by strong feelings, intense thoughts, or the stories we have made up about what has taken place.

The next time you’re in a meeting, try this: Push your chair back slightly from the table, look inside yourself, and see what you find. Scan your body, checking for tension in your vulnerable spots. Mine are the jaw muscles, neck, chest, and back. Notice what you are thinking and decide if it’s helpful. Is it supporting you and helping you achieve the state you decided you wanted to be in, where you display your best leadership? Sometimes when I do this I discover that I’ve brought inner “stuff” with me into the meeting from elsewhere that is affecting my performance here and now.

For many years I sat on a medical/scientific committee that, among other things, organized medical coverage and drug testing for large international events held in Canada. Our meetings took place several times a year, from seven until ten o’clock in the evening. The agendas were often ambitious, and there was pressure to get things done on time. I remember arriving a bit early for one meeting and chatting with the chairman, Norm Gledhill. He said to me at one point, “Peter, you’re not your usual chipper self. What’s going on?” I immediately dismissed his question, said I was fine, and sat down, feeling a bit irritated. But then I slipped inside and quickly noticed that I was not fine and that I was more than a little irritated.

I thought back to dinnertime and realized I had been irritated even then, but when I retraced my day, I remembered that lunchtime had been a much different story, with a lot of fun and laughter. I asked myself, “What happened between lunch and dinner?” Through some inner detective work I was able to realize that it was a mid-afternoon phone call from someone I really didn’t care for that had set me off. This person had asked me to do something in the evening meeting that I didn’t think was ethical.

So let’s take stock here. It was seven o’clock at night and I was still irritated by a phone call from someone I didn’t respect that had occurred four hours earlier. I was giving this person way too much control over how I felt and, as a result, over my behavior. I had to get rid of him! I was giving him attention—attention he didn’t deserve. I could have taken any number of actions. I could have used the centering breathing technique to reduce my arousal level and calm down. I could have reframed the situation or changed the way I was speaking to myself. But what I chose was to run an image: a letting-go image.

First, I thought of him and what he reminded me of. That led directly to the image that would allow me to get rid of him. I won’t tell you what he reminded me of, but you’ll probably figure it out from my imagery. As I sat there in the meeting I imagined flushing this arrogant man down a toilet. I could see him spinning around in the bowl, his tie sticking out in Dilbert fashion, his pompous voice saying, “You can’t do this to me” … and then he was gone! And he truly was gone. I was back to being myself and able to join in the meeting with my usual enthusiasm.

The beauty of meetings is that the opportunity to disidentify is present at many points, and absolutely no one knows you’re doing it. The bonus for you and for them is that when you come back moments later, you’re a much better team player.

Debbie Muir’s story near the start of this chapter concerning her high heart rate at the Los Angeles Olympics is a great example of active awareness. So is the following one from gold medalist David Hemery, describing the last half-hour before the 400-meter hurdle race, which he won by seven meters in the Mexico City Olympics of 1968.

“I have used imagination before a race to keep the nerves under control. Before a race you would have fifteen minutes with your competitors in an area about the size of a small changing room. I would lie down on a bench with my head resting on the soft side of my shoes and close my eyes and try to take my breathing down to slow my heart rate so that I was under control.

“One of the favorites started jogging, so the others also started jogging, but I thought, ‘I’ve got time on the track, so just stay under control.’ I was trying to keep mentally under control through physiological methods.

“On the warm-up track I stopped at the outside of the track, but facing the track, and was changing from jogging shoes into spikes when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw Jeff [an American runner] take a start from the blocks. The movement was so fast it caught my eye. I watched this guy go round the bend and I thought, ‘Gosh he’s fast,’ and I could feel my heart reach into my throat and then I thought, ‘I’m supposed to run faster than that?’ I recognized the lack of helpfulness of that thought! I couldn’t control how fast he ran.

“I immediately switched my thoughts to, ‘When did you feel the best you could, running with power and control and feeling great?’ I thought about coming back from a hamstring tear the year before and going to the beach at Duxbury on the coast in Massachusetts. It was a long beach, with firm sand and shallow water at the edge. I had gone into about six inches of water and was running like a trotting horse. The cushioned landing wasn’t hurting the hamstring, so I gradually moved up the pace until I was running at about a pace you would run a 400-meter lap. I was really moving well, and I held it for what seemed like hundreds and hundreds of meters. I couldn’t believe it! And then I took it up to a full sprint and I must have gone for at least 150 meters at a full sprint, to a point when I started easing back and thinking, ‘Oh my God, what a feeling!’

“So on the side of the warm-up track in Mexico City I told myself, ‘Take your shoes and socks off, the infield is damp from the afternoon rain. Run on the infield for fifty or a hundred meters … take yourself back to the feeling of flow.’ I did, and within fifty meters I was back on the edge of the water with the sun on my back, feeling the power of running freely. The other stuff had gone and I was just within my own power—with the best sense of well-being I could have experienced—of strength, and speed, and power, and enjoyment of movement. It set me up to be able to act on what I could control. There is nothing you can do about the opposition.”

There you have it. Disidentify, notice what is happening, choose what you need to do, and act. Oh, and go out and win the gold medal!

In contrast with John’s story earlier in this chapter, where his performance with the buyer was sabotaged by what he was experiencing, David was able to step back at the critical moment, disidentify, and regain his gold-medal confidence.

When you disidentify, you simply step back from what you’re experiencing and move to a position of neutral observer. When we identify with what we are experiencing—fear, disappointment, insecurity—we begin to shrink and become much less than we truly are. When we disengage and observe what we are experiencing, we expand what is possible because we can access all of our abilities and skills.

Here is a more concrete example: My wife, Sandra, went to a small resort many years ago to do a presentation to a group of recreation specialists, many of whom were her colleagues and peers. The night before the presentation she inadvertently locked herself out of her room, and because all the staff had gone home, she had to sleep, somewhat uncomfortably, on a small couch in the room of one of her friends. She finally got into her own room in the morning and was getting ready for a full day of presenting when she noticed that she was feeling “off” and her confidence was wavering.

She literally stepped back from herself and observed what was going on inside. She noticed that she was tired, anxious, and a little worried about presenting to her peers. But she was also able to see that this wasn’t the whole picture. Managing yourself is not about denial or pretending that everything is okay. When you disengage and disidentify, you may see that you are anxious, tired, worried, or whatever else—but that’s only part of the whole truth at that moment.

Sandra asked herself, “What else am I? What else is also true?” Stepping back and disidentifying enabled her to capture all of who she was at that moment. She was able to remind herself that she was also competent, well organized, respected, a good teacher, and someone with a keen sense of humor.

Psychologist and meditation expert Tara Brach says that all “disease” is “home” sickness in that we need to remember who we truly are and return home—that is, back to our true self. She talks about how we shrink when we become what we are experiencing and become less than we truly are. We become a sliver of the pie rather than the whole pie.