CHAPTER 7

Embrace Adversity

“In the past, in any situation that wasn’t going well or where things didn’t work out the way I wanted them to—in other words, in which I was facing adversity—my first reaction was to blame others or work harder—do more of what I was doing and try to do it better. I had a philosophy professor sit me down one day and say, ‘If you took half the energy you put into telling me how unfair it all is and tried to work harder at unraveling and acting on the lesson this disappointment presents you with, not only would you be stronger, but it would also make it a lot easier for the rest of us to help you and work with you.’ Initially that just irritated me. One day I was reading about Jerry Garcia, late singer of The Grateful Dead …

“I read this interview where Jerry was talking about change and dealing with difficulties, and he said something like this: ‘Somebody has to do something, and it’s just incredibly pathetic that it has to be us.’

“I realized that I could continue to apply useless effort trying to change what was happening, or I could change myself and my reaction to what was happening and figure out a course of action that might move me forward.” (workshop participant)

Dr. Dabrowski firmly believed there could be no authentic growth without adversity. He believed that it was adversity—a crisis—that created the inner turmoil of emotions that eventually led to engaging the Third Factor and moving to a higher level. In Dabrowski’s theory of “positive disintegration,” adversity leads to the disintegration of the person’s current inner milieu and the harnessing of “over-excitabilities”—a susceptibility to strong feelings and intense emotional reactions. The Third Factor eventually leads to reintegration at a higher level of moral and emotional growth.

We will be looking at a “lighter” version of the theory here, but the same fundamental self-transformation is in action. Only when you fail or are challenged do you get to discover what you have, what you don’t have, and how strong your own resources are. Ben Zander, conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, points out that for teachers, success and failure are equal, and it isn’t until we fail that we learn something.

There are some very good outcomes when we embrace and overcome adversity. It’s a tremendous confidence builder, and the confidence built is the real thing, not the sometimes phony, imitative, “talking-like-I-might-be-able-to” kind. The good (and bad) news is that in today’s world we certainly have ample occasion to deal with adversity.

In the work world, the history of the past few decades clearly indicates that change, volatility, uncertainty, and other adverse conditions are here to stay. In other words, you can expect more of the same “weather” in the work world that you have already been experiencing. So why not coach and develop in others the attitudinal skills, attributes, and competencies that will make them exceptional at quickly adjusting to and performing well in adverse conditions?

Two years ago in a workshop I was conducting, I asked the class to generate a list of competencies that would best help people deal effectively with change. We were discussing the fact that there are those who seem much more able to adjust and adapt when change occurs, while others are still dragging their feet weeks later. Someone suggested that one of the primary reasons coaching was emerging as the “go-to” management style was that it was so effective at dealing with situations where we don’t know all the details but need to continue to perform at high levels. This person described coaching as “uncertainty management.”

The world of sport is a terrific laboratory in that high pressure, continual change, and uncertainty about the outcome are the order of the day—everything from severe injuries suffered by key personnel to last-minute changes, from losing streaks to bad weather. One of the coaches I interviewed about this subject put things in perspective when he said, incredulously, “What would you be doing in sport if you couldn’t deal with adversity? That’s what it’s all about; that’s the nature of the game.”

On a typical training night in November prior to the Beijing Games, for example, I was working with some hurdlers when the Canadian champion pulled her hamstring while doing a simple, routine training run. And when twenty-six-year-old downhill skier Jan Hudec was just a few hours away from signing a major endorsement deal, he crashed in a training run, broke his thumb, and seriously injured his knee. Yet his comments the next day not only affirmed that he was feeling positive about the rehabilitation process but also spoke volumes about his ability to deal with adversity and his Third Factor:

“I have a pretty good track record of coming back from injuries and being able to perform well,” declared the champion skier (silver medalist at the 2007 World Alpine Ski Championships). “With all the doctors that have been working with me, I have a good shot at this, so I am not too worried. I’m grateful for coming back and having such a great start to the season, and that’s what will keep me motivated. I’m planning to come back stronger than ever from this.”

What is adversity? Individuals have different thresholds, and what is a threat or danger to one person is a challenge to another. Genetic background and upbringing probably determine, to some extent, just how far each of us is able to go in embracing adversity, but we all can get better at it. There is no safety in inaction. Helen Keller probably said it best: “The timid are caught as quickly as the bold.”

International figure skating coach Doug Leigh and I were talking once about one of his athletes, who was having a rough go of it. The skater was experiencing a series of challenges that seemed terribly unfair—from nagging injuries to serious family matters. Doug commented, “Most of life’s lessons are not friendly.” At the personal level Doug knows of what he speaks, having dealt with cancer twice in his life.

Once again, what distinguishes coaches who are good at developing others is the conviction that adversity can be the best teacher. As we saw in the case of Illinois track coach Gary Winckler in Chapter 1, good coaches move almost immediately into action, consciously shifting perspective, assessing, and then taking action. They see adversity for what it is: another opportunity to ignite the Third Factor in their athletes.

It goes without saying that it’s easy to bring effort to any endeavor when things are going smoothly and we are accomplishing whatever we are working on. Only when adversity rears its head, however, can we truly see how far an individual has progressed in his or her development. Competence is about being able to “do it” (whatever “it” may be) in the real environment, when it counts. You may strike golf balls with tremendous consistency on the driving range, but your level of competence is determined by what you do when playing competitive golf, with all the challenges that real-life circumstances present.

In the same way, you may be an excellent communicator in meetings where there is consensus and people are getting along. But you won’t know how competent a communicator you truly are until you perform well under more adverse circumstances. Both sport and the workplace present us with countless opportunities to embrace adversity and to see it as the teacher and opportunity that it is.

Dealing with Adversity = Stronger Performance

I asked decathlon coach Andy Higgins about the need to embrace adversity if you are to develop others effectively. Here’s what he had to say:

“That’s not discussable, in that it is an absolute principle. No one is going to become excellent, competent, or achieve mastery—any of those things—without consciously seeking to push the boundaries. And you cannot push them without running into adversity and having disappointments. The only way to move beyond them is to accept them for what they are: lessons that will give us what we need to take us to the next level. If we were capable of going to the next level, we wouldn’t have the disappointment, setback, whatever. T. S. Elliot said, ‘Only those who dare to go too far will ever discover how far they can go.’”

British coach Frank Dick had this to say in response to my question about the need to embrace adversity:

“Do you think you will encourage human development in our athletes by solving their problems? The truth is, that never develops people. You only develop people by giving them the right level of challenge. That is what coaches do.

“Do you think Linford Christie became the fastest athlete in the world by running against slow people? You have to look at the tough situations. You have to get into the white water. You have to understand that by overcoming these things you are stronger not just for what will happen the next time you compete, but stronger for life. It is overcoming these things—the difficulties of life—that gives you the character to make sure that when you do move on, the energy is passed on to a new generation of athletes. You and I know that whatever mountains we have had to climb in the past, there will be tougher ones in the future. That’s just the way it is, and you learn to have the character to go for the tougher mountains.”

Success in sport and in life is all about learning to deal with and overcome obstacles and challenges. In today’s fast-paced workplace, can you really afford to have people who drag their feet and become paralyzed when they encounter unexpected changes, disappointments, setbacks, failures—in other words, adversity? Of course not. But as a leader you have a role to play in developing in those under your care the skills that will allow them to embrace the adversity and turn it into the developmental opportunity it truly is. You can dramatically accelerate the development of the Third Factor in performers by helping them change their perception in adverse situations and overcome obstacles, thereby increasing their level of confidence and competence. There are big wins to be had in helping others deal effectively with life’s challenges.

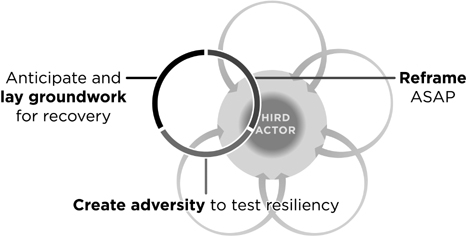

The three tips that follow will help your performers successfully face—and embrace—adversity: anticipate and lay groundwork for recovery, reframe as soon as possible, and create adversity to test the resilience of your performers.

Anticipate and Lay Groundwork for Recovery

This one definitely isn’t “rocket science,” as the kids say. Planning to reduce the impact of adversity is an obvious course of action. But is it effective? To clarify, here’s what anticipating isn’t: it isn’t expecting failure, it isn’t talking to the performer about all potential disasters, and it isn’t setting low standards.

It is about anticipating what obstacles might arise and coming up with a plan to deal with them. Tremendous confidence comes from having a plan. Adversity is a way to test that plan and further build the performer’s (and coach’s) confidence.

An experienced coach has a pretty good idea of all the possible pitfalls and traps the performer might fall into, and it’s the coach’s job to ensure that the performer has thought about these and is equipped to deal with them. I continually ask athletes what they plan to do if this or that or the other thing occurs. Which doesn’t mean the worst will happen. (Nor does it mean they will follow the plan and avoid the adversity!)

Prior to the 1987 world figure skating championships in Cincinnati, Ohio, I got a call from Michael Jiranek, Kurt Browning’s coach, saying he couldn’t be in Cincinnati for Kurt’s first practice and would I look out for him. I stood at the boards with Rosemary Marks, the team leader, during Kurt’s first practice. Kurt had a plan to warm up slowly and not get distracted by the exceptional group of skaters on the ice with him at the time, including Brian Boitano, then current world champion, and Brian Orser.

Someone had decided it would be a good idea to sell tickets for the practice, so there were some fifteen thousand spectators oohing and aahing at every jump. Rosemary and I saw very little of Kurt in the first twenty minutes as he tried to outjump everyone on the ice. He came by for drinking water once, looking fairly exhausted, and left the ice a bit before the end of the forty-minute practice. As we were walking down the hall to the locker room, Kurt said to me, “I just did everything I vowed I would never do in my first practice at worlds!”

By acknowledging this, he demonstrated great awareness and a perspective that quickly led to recovery, because he still had a workable plan and he knew what he wanted to do. He had just been blown off course by the crowd and by his own desire to please them, but he was already on the road to recovery.

So the coach’s first line of action is to try to anticipate all the problems that might arise, and to help the performer develop a strategy for dealing with them—if they happen. Adversity usually occurs when the performer doesn’t perform up to par or, worse, has a devastating experience—as gold medal favorite Perdita Felicien did when she fell right out of the blocks in her race at the 2004 Olympics (described in Chapter 1).

Good coaches/leaders are always playing the “what if” game: What if my best performer gets hurt, what will I do? How will I talk to the team and what, specifically, will I say? What will my strategic response be in terms of deployment of resources? What if the plant remains closed past the expected retrofit time frame? Suppose we get off plan by 5 percent in the next quarter, what options do I have? How will I talk about it to the team in a constructive way to help with the second-quarter recovery?

You don’t want your people to fail. You don’t want to create a high-stress, reactive environment. You want your people to be able to handle adversity effectively and be resilient in the face of it. You need to coach to those expectations. No golfer wants to be in the sand trap, but the good ones anticipate and prepare for that possibility.

Mel Davidson, who coached Canada’s gold medal-winning women’s Olympic hockey team, told me, “I really think that if you’re prepared going in, the adversity is easy to handle. If you can focus on how it’s affecting everyone, then it can be advantageous, but if you are not prepared going into an event or competition, or even in practice sometimes, then your reaction is usually poor and you don’t handle it well and it isn’t a learning experience, it isn’t a growth experience.

“At Hockey Canada, CEO Bob Nicholson, under whose tutelage I basically grew up, is a firm believer in dealing with adversity. I remember going to events and something would happen and I would think to myself, ‘Bob did this, Bob did this! Things were going smoothly and he sent this so we would have some adversity!’” Bob also ignited Mel’s Third Factor by helping her begin to self-direct her own growth as a coach in a very male-dominated world: ice hockey. It’s no accident that she was one of the few women ever to coach Junior A men’s hockey!

Hold a Broad Perspective

Perspective is critical to success in stressful or crisis situations. Just as location, location, and location are the three keys in real estate, the three essentials in the coaching process, for both leader and prodigy, are perspective, perspective, and perspective—especially in times of adversity. The leader’s primary functions are to maintain a developmental perspective and to uncover and, if necessary, tweak the perspective of the performer.

I asked Andy Higgins what role he, as a coach, takes in helping his athletes deal with adversity.

“To me that’s the only role a coach has. Everything else can be done by a trainer. Trainers prepare and carry out programs; coaches deal with the human being and all the things I already talked about—setting it up early on, knowing where the real work has to be done, developing the awareness—that’s the coach’s job. The coach’s job is to support awareness for starters because the awareness will prevent some of the difficulties from arising in the first place.

“The next question is, what do we do when we come up against a difficulty? One of my corporate clients had to declare personal bankruptcy. I called him and asked, ‘Neal, why haven’t you called me?’

“He said, ‘Why haven’t I called you? I owe you money. It’s embarrassing.’

“I said, ‘Neal, you didn’t hear me. I said why didn’t you call me, not where is my money. You don’t need me when things are going well. You’re in the deepest hole of your life now. Now is when you need me.’

“That’s really when a coach is of value, when someone is facing a difficulty—large or small. My job is to support the development of the person who is performing the skill, whether it’s selling insurance or something silly like jumping these hurdles.”

Being a leader, you need to reinforce the bigger picture for those under your care, continually reminding them to focus on two things: what is happening now, and their overall self-image. Sometimes the most helpful thing you can do is to remind them, at critical moments, of all that they are. In a high-pressure situation it’s not unusual for every one of us to lose perspective on our capabilities and competencies. It’s helpful to be reminded of all we have dealt with and overcome in the past—problems we may at the time have thought insurmountable—and to realize what an arsenal of skills we possess. Recalling this is empowering and truly ignites the Third Factor.

There is a wonderful Zen perspective exercise that many masters employ with their students. In the middle of a large piece of paper the master draws a small, V-like figure. He then asks the students, “What is this?”

The students respond with various ideas, from a bird to a wave. The master points out that it may indeed be a bird or a wave, but then broadens their perspective. He shows them that they have become so focused on the foreground that they have missed the background and therefore the “all” of it. If it is a bird, then it is a bird in a huge sky. If it is a wave, then it is a wave in a huge ocean.

In times of adversity it’s easy to get caught up in the foreground, in what is happening now, and to forget the big picture both in terms of the end goal—what you are trying to achieve—and your own competencies and capabilities—your own Third Factor.

Your job as coach is to direct the attention of others to what is most important—to those aspects of the situation that can be controlled and where action might matter. Situation mastery is about acting where you can make a difference and letting go where you cannot. It’s all too easy for some performers to give up in the face of hardship, and that can be a challenge for any leader. But the tougher issue to deal with is ceaseless striving—trying to change what cannot be changed, applying effort where no amount of effort will matter. We deal with this later, in the section on reframing.

One can misrepresent or misinterpret the directive to “anticipate and lay the groundwork for recovery.” Does this mean you should go into a situation expecting the performers to fail? Do you make statements like “Look, don’t expect too much from yourself” or “Don’t worry if you’re not successful or fail completely”? Of course not. Keep in mind that what you are trying to do is build a strong, independent performer. So pre-event conversations should encourage them to develop their Third Factor, while at the same time allowing you both to lay the groundwork for recovery in case something goes awry.

You can’t debrief any performance properly unless you know what the performer was trying to accomplish in the first place. I often ask questions like, “What are you hoping to accomplish? What’s your strategy or plan? What’s an outcome you could live with, one that would be very good, and one that would be unbelievable?” I recently put that last question to an 800-meter runner I was working with whose first indoor meet in which she was running a 600-meter race was coming up that weekend. I asked her to give me a time for 600 meters she could live with, and she said 1:29. Her very good time would be 1:28.5, and an unbelievable time would be 1:27.5. I told her that when we debriefed after her race on Saturday, I would refer back to those times. What was the purpose of doing that? People often change their expectations and thus create their own adversity. So if she were to run, let’s say, 1:28.8 and place last in the race, I now had concrete times I could remind her of during the debriefing—ones that she herself had laid out as criteria for success.

On joint sales calls, the manager needs to ask questions ahead of time related to call objective, strategy, and plan, so that if a disaster does occur, there is a frame of reference for later discussion. As a leader you too want to think ahead to the possible outcomes and how you will deal with them in a developmental way. Your self-management as a leader is especially critical when performance results are at either extreme—a huge success or a devastating failure. It’s hard to be developmental when you are caught up in your own reactions.

Anticipating and preparing the groundwork for recovery has to do with what your performers attribute the failure to. After a tough quarter or year, you want to make sure that the people in your department or work unit clearly understand the reasons for the disappointing results—all the contributing factors. After the analysis, they also should be able to see a course of action, a way to recover. You really need to paint a believable picture of recovery.

As a leader, when you anticipate the possibilities you can also work in advance to lessen the psychological blow on the performer and start the re-engagement of the Third Factor in team members much sooner. In most environments today, big surprises can be kept to a minimum if you can see things coming. An authentic leader won’t panic but will simply point out the obvious: “We are not going to hit our numbers because of A, B, and C. What opportunities do people see here?”

Coach Gary Winckler told me about pushing Perdita Felicien around the Olympic Village in a wheelchair the evening of her Olympic disaster in 2004, thus starting right away to help her process what had taken place. I commented that in a situation like that it is always helpful to begin the process with the performer immediately in order to intervene in a possible downward spiral.

“That’s so true,” he said. “You want to blame someone, you want to blame something. The evening after it happened I hadn’t had any time to look at a video and couldn’t tell her exactly what had happened. The next day I looked at video for hours, from all different angles, and I still couldn’t tell what had happened. As I was telling a reporter the other day, it was just one of those things that happens. Every hurdler is like every bull rider; you know you’re going to fall, you know you are going to trip up at some time. It’s inevitable. That’s the risk you take in doing the event the way it’s supposed to be done. I tell my hurdlers, ‘When you feel like you are on the edge of being out of control, that’s when you are running your best. You have to accept that and be cognizant of it. One of the things you have to do is not fight it, to go with the flow, like you’re running down the hill, over hurdles in the dark. You know where they are; you just have to continue to go with the flow. As soon as you start to get scared and back up and fight that flow, that’s when you are going to go down.’”

I said to Gary, “You took an active role with Perdita in dealing with her adversity.”

“Well, you come out the next morning and every media guy in the world is going to ask her what happened and how it happened, and four years later she’ll have to go back and have this discussion again, because it’s going to start all over again [in the Beijing Olympics]. Overcoming adversity is what sport is about.

“I had another athlete, Tonya Buford Bailey, who broke the world record in the world championship race in 1995 and still placed second—by one hundredth of a second. You cry one minute, you’re laughing the next. She always had the greatest attitude: ‘I know I’m going to lose more than I win,’ she said. That’s a pretty healthy attitude when you’re willing to accept that fact, but it doesn’t detract from what you are trying to do. You are very fortunate if you ever reach a point in your career where you win more than you lose.”

Reframe ASAP

Anyone who has ever framed a picture or a painting knows that when you change the color or style of the frame, the picture looks different. The picture doesn’t change, but a blue frame and matte will highlight the shades of blue in the picture, whereas a black matte and frame show up the darker colors. Similarly, life may determine events and outcomes, but the choice of frame is ours. We can consciously select the frame that highlights the developmental opportunity rather than the obstacle or setback.

During the deregulation of the telephone industry in the 1980s, Suzanne Kobasa and Salvador Maddi, two researchers from the University of Chicago, conducted an interesting seven-year study with two hundred middle managers of the Illinois Bell telephone company. They studied these executives as they went through turbulent changes in their industry, staying in constant communication with them and performing annual medicals on them. At the end of the study it was clear that some of the managers had thrived while others had not. Of those who had failed to thrive, one of the major indicators was a rate of absenteeism from work due to illness six to seven times higher than among those who had successfully withstood the stress. In examining the differences between the two groups, Kobasa and Maddi discovered that there were three main resistance resources that allowed people to stay healthy and perform at high levels: personality hardiness, exercise, and strong social support.

The likelihood of illness developing in stressed executives was 93 percent if no resistance resources were present, but less than 8 percent if all three resistance resources were present—a colossal difference, to put it mildly. Exercise and strong social support had what the researchers called a small buffering effect. This is understandable. Exercise may help to reduce the stress, but you still have to go into the work environment every day, and strong social support would soon start to decline—in my house anyway!—if I continued to come home complaining about my job for seven years.

The factor that most strongly influenced the health of the executives was personality hardiness. These people optimistically appraised events and took the decisive actions that would alter them. They did this by embracing the three Cs: commitment, control, and challenge. They chose to see what they were going through as interesting and important (commitment), capable of being influenced (control), and of potential value for personal development (challenge). What they were doing, of course, was reframing: choosing to take a perspective of events that would help them move forward. This action-oriented perspective activates the Third Factor, helping people move from “what is” to “what ought to be.”

Modes of Reframing

The method of reframing that you use and how you use it will depend on the nature of the situation you are faced with and what you or the group most needs. There are times, for example, when you need to find the energy to tackle a difficult change. At those times what the group may need most is the energy just to begin the process. Often, sitting down and brainstorming what the opportunities are in dealing with this issue is the first step. Perhaps you ask the question, “What would be the benefits if we dealt effectively with this issue?” When you see what you might gain, you usually see the upside to handling an issue effectively, and that enables you to find the energy to deal with it.

A second mode of reframing is to sit down with the person or team and, as a first step, let them “awfulize” about it, to use a term coined by psychologist Joan Borysenko. You might ask, for example, in a situation where significant change is required or is already taking place, “What are the dangers in going through this change, in making this transition?” Allow people to list all the inherent dangers. If you’re an optimist, this tactic might be a little hard on you. Optimists hate to hear all the negative stuff. But don’t stop the process—just let it all come out. Then start at the top of the list and work on each item, deciding which you have control over and which you don’t (and therefore need to let go of). Of those you have control over, you can now ask the three questions from the hardiness study: “What aspects of this do I have control over?” “Is there anything I can see as a challenge for personal growth and development?” “Is there anything here that I can commit to?” It is always surprising in any situation to discover how many possibilities there are for action. This discovery recharges and re-engages the Third Factor in those involved.

A third method of reframing is simply to say to the group or the individual something like, “We don’t want to go through this and we don’t like having to go through it, but seeing as we have no choice, where are the opportunities?” Taking a situation that you’re faced with and making a decision to look for the opportunities is the simplest and most direct way of reframing.

Victor Frankl, in his landmark book Man’s Search for Meaning, pointed out that the one thing that can never be taken from us is our attitude toward a situation. He called perspective “the last human freedom.” Because of his own experience he believed that meaning saved lives in the German concentration camps, that given the chance, those who were somehow able to create a sense of purpose and meaning out of what they were going through were the ones most likely to survive. Extreme though this example is, it does make the point: Life may choose what we have to deal with, but we choose the perspective we take. Frankl’s book is in line with Dabrowski’s theory about the Third Factor; it is about moral and emotional growth in the darkest of times.

The sooner we start the act of reframing, the better. Immediacy is important for all postperformance discussions. Coach Gary Winckler makes it clear that he wants to talk to his athletes about their performance right after an event, no matter how it went.

“I tell every athlete after a performance that I want them to come and talk to me. Whether it’s just a small competition or a major event, we will talk about what happened. We will analyze what went well and what went wrong. We’ll talk about how we can fix it—and then we’re going to forget, we’re going to move on—take the things we need to work on and move on. That’s probably adversity at its lowest grade, just figuring out how to move forward and not dwelling on what happened in the past. If I take a video of the race and it’s a disaster, the video is never seen by the athlete. It’s just never looked at again. You can’t learn anything from it. Every day in training, your attitude has to be, ‘I’m going to learn something from competition and I’m going to try to use that information to make the next time I do this a better experience.’”

Reframing is also a great team/group skill. I once worked with a group of leaders in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who were faced with the challenging task of helping their people through a difficult transition. The more than six hundred employees in this organization had no idea if they would have a job three months down the road. Their organization, a large oil company, was merging with an even larger one, and it was clear that the culture of the larger company would become the dominant one. The employees didn’t know whether they would receive a buyout, see the company sold out from under them, end up in a new, separate company selling their services back to the merged organization, or simply stay on as employees in the new company.

I spent a day talking with the leaders about how they might assist their people at this difficult time. We spoke of many things, including reframing. The reframing took the form of a facilitated exercise in which the leader drew a line down the center of a flip-chart page and on the left-hand side encouraged the group to generate a list of all the dangers inherent in their current position. People were encouraged to “awfulize.” I reminded the more optimistic of the leaders not to cut this list short—optimists often want to jump to a solution too quickly. Once the employees had exhausted all possibilities for this list, I encouraged them to go to the blank right-hand side and, taking each item on the left side, generate a list of possibilities from the three Cs in the hardiness study: control, challenge, and commitment.

They addressed each item with questions based on those three Cs: “Is there anything here over which we have control?” “Is there any aspect of this that I can see as a challenge?” “In relation to this item, is there anything I can commit to doing?” It wasn’t long before they started to see some possibilities they could begin to act on. Now I am in no way suggesting that these opportunities were preferable to not experiencing crisis. But when you are in a crisis you might as well figure out where you can best act and where you need to let go so you can ignite the group’s Third Factor and start them on the road to what is possible.

Create Adversity to Test Performers’ Resilience

The most effective way to build confidence in our performers is through the successful completion of a challenging goal or through the triumphant conquering of adversity. Genuine confidence, real confidence, comes from the successful completion of a task important to the performer. We may praise them and rain accolades on them, but when it comes to developing authentic confidence, accolades pale in comparison with achievement.

This is one of the reasons coaches focus on performance goals and not on end goals. Competence is best developed through a series of successes in the real game, at the real task. And as a leader you can also learn a lot about the “reach” of your performers when they are performing under a bit of pressure you have created to develop them fully. There is an old Buddhist expression, “Every meditation hall needs a fly.” Sometimes you need to create adversity or a challenge to be able to determine how far the performer has developed and to prepare them for the fact that very soon these timelines, this pace, these high numbers, will be commonplace.

I want to point out that creating adversity is not about being mean, it is about being developmental. We have to assist people in moving out of their comfort zone if we’re going to develop them. We owe it to them to prepare them for what we know is coming. The leaders at NASA, for example, put potential astronauts through numerous simulations to develop them adequately for future missions. In my work in sport I have organized many simulations to prepare athletes for the adversity of competing in the Olympic arena. What follows are four examples from the world of sport, and then a look at how this concept might ignite the Third Factor of those in the workplace.

Prior to the 2006 Torino Olympics, the Canadian women’s Olympic hockey team was playing an exhibition game against Sweden in Calgary. These two teams would eventually meet in the gold medal game in Torino. The Canadian team was down 2-0 at the end of the first period, a position they had never been in before in any game with Sweden. I expected Canadian coach Mel Davidson to be upset with the level of play, but she was almost giddy as she entered the coaches’ room. Rubbing her hands together, she said, “All right, this is new for them. Let’s see how they handle it!”

On another occasion I asked British coach Frank Dick, “Did you ever create adversity to test athletes?”

“Oh sure, in a very amateur way. Noises when athletes were running up to do, for example, the long jump. When they only had one jump left in the evening … noise of a crowd, music, a starter’s pistol.

“Ian Robertson, who was under my wing as a young lad in Scotland, was coaching two Scottish girls who were going to New Zealand to compete at the Commonwealth Games. Neither had been in a major stadium. Competing in the west of Scotland championships is rather different from a World Games arena. So he set up a deal with the Celtic football club: the girls jogged around the perimeter of the track at halftime and were introduced: ‘These are our girls going to represent Scotland.’ And the crowd roared and both girls came off the track trembling, absolutely trembling. That was a clever move.”

I also asked American Coach Gary Winckler if he trained for adversity with his athletes.

“Yes, constantly. In hurdling, for example, the way I approach the event is that you want to reach this state of abandonment. It’s not a run over ten hurdles; it’s eleven accelerations, trying to get faster each time. When the athlete gets comfortable with a certain spacing of the hurdles, then what I do is maybe put the hurdles closer together to force some things to happen that might happen in a competition. Or we will race with a really big tailwind behind us, where we have to deal with higher velocities than we’ve dealt with before. As you do that, you create problems. You create problems with the takeoff, you create problems with the steps between the hurdles—and it forces the athlete to learn how to adapt to those situations. We spend a lot of time creating adversity in order to get the training effect. You could say it’s just a simple application of the principle of overload. When we try to get an athlete stronger, we increase the overload, make it more difficult. We present the adversity to the training.”

David Hemery, British coach and gold medal hurdler, said he too plans for adversity.

“When I was out doing hill reps in the winter with this not-quite-seventeen-year-old, he agreed to do two sets of four. They were about two hundred meters long. After the sixth one he felt rubbery, after the seventh he threw up and was on his hands and knees. And I thought: ‘I was in my twenties when I was doing this, and he’s not quite seventeen. Do I push him?’ I didn’t make the decision for him. I asked him, ‘Do you want to walk around a little longer?’ And he said, ‘Yes, I do.’ I said, ‘Do you want to go back down to the bottom, back at the start, and decide when you would want to go?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ We went down to the bottom and he took a good two or three minutes’ extra rest and then did a personal best on the eighth one, then threw up again, really in bad shape. And I just said, ‘I am truly proud of you, but I hope you’re more proud of yourself. You worked there to earn your time next summer. You’ll never have to run that hard and dig that deep in a race, but the fact that you’ve been there means that in a race, when it gets tough you will be able to hang on while hurting. You have just earned yourself the times you want to run this summer.’”

So how might you apply this concept to performers in the work world? We put the question to a group of business leaders at two of our seminars. The first story is a good example of how not to do it!

Shaking the Tree. One manager talked about a company with which he had previously worked. There was a change in management, and the new manager who took over his department decided he was going to find out what his new team was capable of, through a process he called “shaking the tree.” Essentially this involved piling on the work, giving his people really challenging goals and tough assignments to see who sank and who learned how to swim and swim well—but providing them with very little guidance or support. The problem is that if you shake the tree too hard, you dislodge not only the bad apples, but a lot of the good ones as well. And unlike apples, people have the inclination and the ability to move to a more stable tree. So while this process did help that manager quickly assess who his best people were, many of those were the first ones to walk out the door—highly sought after, they were capable of landing jobs with other organizations. On top of that, to this day that organization has an underground reputation of being a “hellish place to work,” and it has a tough time recruiting new talent.

The Rich Get Richer. One manager described how the best boss she ever had used to reward his good people by giving them increasingly tougher assignments. But although the difficulty of the assignments did require more time spent on planning and strategizing, it wasn’t a case of just piling on more work. The tougher assignments were characterized by complicated situations, with more legal, policy, and administrative restrictions, greater technical and logistical challenges, and the involvement of more parties/departments/interest groups—in other words, it was really interesting work.

His people loved it. These assignments gave them a chance to hone their skills and develop reputations as “A Players.” They gave these employees increased visibility inside and outside the organization and created a culture of achievement within his department. After doing this for a while, he noticed two highly desirable but quite unexpected results. First, good people sought out his department, which had developed a reputation as a place to go if you were really smart and motivated and wanted to improve your skills for the next level. Second, his people were, as he put it, nearly “immune to the consequences of change.” Because they were used to seeing the value in taking on new and challenging tasks, and because they were good at putting together and executing strategies under such circumstances, organizational change had become routine stuff for them.

Shift in Perspective. One sales manager with an office technology company described how his boss used to help top sales-people make the transition from selling to managing. The challenge this manager faced was that, traditionally, people in sales roles get promoted to sales manager because they are skilled at selling. They know it, and they have been recognized and rewarded for it throughout their career. The tendency therefore is for newly promoted sales managers to “do it yourself” or micromanage the sales staff, behavior they see as being “helpful” or “supportive.”

What this boss did was start piling on the work while staying around and observing the new sales manager closely. These deliberately chosen assignments were ones that could be done by the sales staff but were complicated enough to tempt the new sales manager to take them on instead. After the work volume reached a certain point, the boss would notice signs of overload (longer hours in the office, work taken home, symptoms of stress, lack of visibility outside the office, impatience, slipping deadlines, etc.). That’s when he would have what was known as “the talk,” which essentially went something like this:

“You have unbelievable sales skills, and for many years you have added tremendous value to the organization through using those skills to move our product. That is no longer your role. Your role is to develop, guide, and support your team of hired guns to go out there and sell. I have noticed that you seem to be working a lot of late nights. I know I’ve been sending a ton of work your way. My expectation is not that you will do this work yourself, but that you will hand it off to your people and that you will prepare them, guide them, and support them so they are capable of getting it done. So let’s sit down, take a look at the assignments on your plate, assess where your team is at, and see who might be capable of taking on some of them.”

Why did this manager of sales managers take this approach? It was his experience that until you let people struggle a bit—create some adversity for them—they don’t know that what they are currently doing won’t work in the long term. The realization opens them up to new options.

Three Weeks in Spring. One sales manager with a communications firm developed a routine that she put in place with her sales teams going into the summer months. Her view was that the summer months, particularly in Canada, were for enjoying the fine weather and spending time with family, and she wanted to make sure her people developed good work routines so that the work did not expand to fill up their free time. In the second week of April, she required that they work no more than a forty-hour week; in the second week of May, no more than thirty-five hours. And during the second week in June (when there were always many social events and school-related commitments), they were to try to meet their targets working a thirty-hour week. At the end of each week they would share with each other systems, processes, and tricks that they had found helped them to get the work done in the time allotted.

In her mind this achieved several major goals. First, it really drove home to her people the point that she expected them to enjoy a life outside of work. Second, it created an environment where people were challenged and excited to think about being more efficient—but with the goal of having more time for themselves, not just to get more done for the company. And finally, she found that when they really had periods of challenging targets to meet, the lessons of the three weeks in spring provided useful skills and systems that helped them.

Growing While Giving Back. One sales manager with a high-tech company used charitable endeavors as an opportunity to expose his people to adversity and grow the capabilities of his team. Each year the team chose a special project that would significantly benefit the lives of people much less fortunate. Then, based upon the chosen target, they would put in place a challenging goal. In each case, the sales manager would push the team to set a really audacious goal, one in which the chance of failure was estimated to be at least 30 to 40 percent. There were only a few rules attached to this endeavor. First, it had to be a new cause each time. Second, the role of spearheading the effort had to rotate among individuals each year. Third, there were guidelines/limits for how much they were expected to contribute personally in hours and funds.

If the team reached its goal, they would have a celebration party. If they failed, they would have a “wake.” In either case this took the form of a family barbecue hosted by the sales manager at his house, where he provided all the food and drink and he and his wife and kids cooked and served the guests.

He found that this charitable endeavor provided a safe environment for his team to challenge their abilities, work together as a team, and try out new roles (project leadership, planning/strategy, finances, marketing/communication). The fact that it was a new project each year helped keep things fresh and forced people to be creative and not just work off past templates. It also encouraged dialogue as they tapped into the expertise of the people who had had their roles the previous year. The added bonuses for all this effort were a contribution to a worthy cause, an opportunity to celebrate together, and a sense of perspective about what was really important.

Confrontation = Creating Adversity

There will be times when you have a change you want a performer to make and you have tried questioning, feedback, and the other, more collaborative communication skills, but the person is still not engaged in the desired behavior or at the required performance level. When this happens, you will need to move into a more confronting style of communication. The act of confronting can create adversity for both the recipient and the leader, but it will occasionally be necessary if you are to ignite the Third Factor in the person.

You have to be careful not to confront in a manner that is so personal that it shuts the person down. The individual needs to be able to move from being upset with you, or with what you are pointing out, to a more internalized realization and acknowledgment that he or she is not rising to this particular challenge or change. As coach or leader, you need to make sure the “failure” is attributed to something over which the other person has control and can change—through increased effort, for example, a shift in perspective, a newly perceived chance to learn, or a willingness to risk trying and “failing.”

Positioning the issue as a developmental opportunity is far more helpful than focusing on it as “a major problem” (except in the fairly infrequent circumstances where this is really called for). And making your expectations clear (“I know you can do this”) reinforces the message that a positive outcome is achievable. If you position any conflict in a developmental way you will engage the Third Factor in the other person and increase that person’s motivation to be “more like this” (a future state) and “less like now” (the present state). For those who really want to delve into the “how-tos” of confronting, Appendix B includes a detailed map for this challenging process.

I once had a meeting with a figure skater named Ben Ferreira. I was reviewing with him a self-assessment he had written. At those times it’s sometimes difficult to hear about shortcomings or personal challenges and not get defensive. He did his best to be open to his results, then accurately captured the moment by saying to me, “The truth will set you free, but first it will piss you off!”