Chapter Five

The Beginnings Rulebook I

The Risk-Proof Beginning

“The beginning is the most important part of the work.”

—Plato

“Always dream and shoot higher than you know you can do. Don’t bother just to be better than your contemporaries or predecessors. Try to be better than yourself.”

—William Faulkner

Publishing has always been a risky business. But in today’s volatile landscape, the publishing business is riskier than ever. And getting published can be tougher than ever, especially if you’re a debut author and your aim is to be published by a traditional publisher.

There are only so many spots on a publishing house’s list, and most of those spots are already taken by established writers. To make that list, you need to be better than your best, starting at the very beginning of your story. To make sure that you’re putting your best story opening forward, you need to risk-proof your beginning.

In the thousands of story openings I read each year, I often see writers taking risks that effectively eliminate them from the competition, no matter how good their story ideas are. These risks involve questionable choices regarding the elements of fiction; many writers make these poor choices out of ignorance or arrogance or simply a gross misunderstanding of the marketplace.

As a debut author—or an author trying to break into a new genre or make the leap from a small publisher to a bigger one—you can only afford to take so many risks. In fact, the fewer risks you take, the better. And if you must take a risk, then you need to amortize that risk.

Start by conducting a risk assessment of your story. To do this, follow along with me as I share with you the rules regarding the elements of fiction, which you break at your peril. In this chapter, we’ll look at the intricacies of the softer and subtler elements: voice, point of view, character, and setting. In the next chapter, we’ll tackle the sharper elements of action, conflict, dialogue, and theme.

We begin with voice, the storyteller’s instrument.

Voice

“I thought I was clever enough to write as well as these people, and I didn’t realize that there is something called originality and your own voice.”

—Amy Tan

A strong and original voice is a beautiful thing that can make your career as a writer. Just look at writers as diverse as J.D. Salinger and Anne Lamott, John Irving and Nick Hornby, and Jane Austen and Elizabeth George. Their unique voices played a starring role in their success. Strong voices—whether funny or brooding, satirical or lyrical, elegant or elegiac—are a critical selling point for writers and can make the difference when it comes to getting published.

That said, just as all strengths can be weaknesses if you rely on them too much and/or too often, a strong and original voice can be a weakness as well. Many writers fall in love with the sound of their own voice and rely on it to the detriment of other elements. They fail to realize that voice is the sound of the story, not the story itself.

If you consider voice one of your strengths, then you must ensure that you are using it to your best advantage. Go through your opening scene, and make sure that you:

- Show; don’t tell. Writers with a strong voice are especially prone to telling, rather than showing, their stories. This can be particularly true in the opening pages of the story. Break yourself of this bad habit, which can sabotage your efforts to get published.

- Employ all of the elements of fiction. Action, conflict, setting, dialogue, description, theme, etc.—all of these elements should be well-represented in your writing.

- Eliminate chunks of navel-gazing, editorializing, or proselytizing. Let your story speak for itself; don’t drown your drama in pointless inner monologue.

Aim to use that strong voice of yours to enhance the action, reveal character, and, most of all, keep the reader engaged, as in the following examples of opening scenes marked by their writers’ original voices.

Tyler gets me a job as a waiter, after that Tyler’s pushing a gun in my mouth and saying, the first step to eternal life is you have to die. For a long time though, Tyler and I were best friends. People are always asking, did I know about Tyler Durden.

The barrel of the gun pressed against the back of my throat, Tyler says, “We really won’t die.”

—Fight Club, by Chuck Palahniuk

Hampton Court Palace, Spring 1543

He stands before me, as broad as an ancient oak, his face like a full moon caught high in the topmost branches, the rolls of creased flesh upturned with goodwill. He leans, and it is as if the tree might topple on me. I stand my ground but I think—surely he’s not going to kneel, as another man knelt at my feet, just yesterday, and covered my hands with kisses? But if this mountain of a man ever got down, he would have to be hauled up with ropes, like an ox stuck in a ditch; and besides, he kneels to no one.

I think, he can’t kiss me on the mouth, not here in the long room with musicians at one end and everyone passing by. Surely that can’t happen in this mannered court, surely this big moon face will not come down on mine. I stare up at the man who my mother and all her friends once adored as the handsomest in England, the king who every girl dreamed of, and I whisper a prayer that he did not say the words he just said. Absurdly, I pray that I misheard him.

—The Taming of the Queen, by Philippa Gregory

It began the usual way, in the bathroom of the Lassimo Hotel. Sasha was adjusting her yellow eye shadow in the mirror when she noticed a bag on the floor beside the sink that must have belonged to the woman whose peeing she could faintly hear through the vaultlike door of a toilet stall. Inside the rim of the bag, barely visible, was a wallet made of pale green leather. It was easy for Sasha to recognize, looking back, that the peeing woman’s blind trust had provoked her: We live in a city where people will steal the hair off your head if you give them half a chance, but you leave your stuff lying in plain sight and expect it to be waiting for you when you come back? It made her want to teach the woman a lesson. But this wish only camouflaged the deeper feeling Sasha always had: that fat, tender wallet, offering itself to her hand—it seemed so dull, so life-as-usual to just leave it there rather than seize the moment, accept the challenge, take the leap, fly the coop, throw caution to the wind, live dangerously (“I get it,” Coz, her therapist, said), and take the fucking thing.

—A Visit from the Goon Squad, by Jennifer Egan

Each of these novels opens with a compelling scene told in a strong and original voice—whether the narrator’s disturbing showdown with Tyler or the distraught young widow Kateryn Parr dreading the inevitable kiss from King Henry VIII or Sasha contemplating stealing a woman’s wallet in the ladies’ room of the Lassimo Hotel.

These examples show how to make the most of an engaging voice, invigorating your story opening rather than slowing it down. Make sure your voice does the same thing for your beginning.

Point of View

“It doubles your perception to write from the point of view of someone you’re not.

—Michael Ondaatje

Point of view (POV) is a tricky bastard. All other things being equal, point-of-view issues have kept more writers I know from selling their work than anything else. So many people get point of view wrong, more than virtually any other element of storytelling. Worse, they often resist fixing it even when they know they’re doing it wrong. Sometimes this is because they don’t know how to fix it, and sometimes it’s sheer stubbornness on their part. But it’s a stubbornness born of hubris, and we all know what happens to characters suffering from an excess of hubris. (If you’re not sure what happens, just reread your Greek tragedies.)

Point of view is one of the most complicated aspects of writing fiction and one of the easiest to screw up. And when you do, you’ll be dismissed as an amateur right there in your opening scene. That’s because point of view serves as a kind of litmus test for agents and editors; if you get it wrong, they will assume that you have not mastered your craft. And they’d be right.

When it comes to point of view, your best bet is to follow the rules. If you don’t, the odds that you will fail are high, so high that I, for one, will no longer work with any writers unwilling or unable to address point-of-view issues in their stories. Every time I’ve made an exception—usually due the writer’s insistence that I shop the manuscript despite the point-of-view problems—I have been unable to sell the story, even when everything else in the story works. I don’t get paid until the story sells and the writer gets paid, so no sale for the writer spells no commission for me. To wit: I have wasted my time, energy, and expertise on a writer who refuses to acknowledge the problems with point of view. Now, that’s hubris. Worse, that’s a good book that didn’t get published because the writer was too stubborn to revisit point of view.

Pardon my rant, which was a long way of saying that this is one risk you should think twice about taking, at least with your first novel. That said, writers who have mastered their craft have earned the right to break the rules. But you need to learn those rules first.

POV Rule #1

Your best bets are first-person point of view or third-person-limited point of view.

First person invites the reader directly into the head of the “I” narrator and as such is the most intimate point of view.

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.

—Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

Through my binoculars, I could see this nice forty-something-foot cabin cruiser anchored a few hundred yards offshore. There were two thirtyish couples aboard, having a merry old time, sunbathing, banging down brews and whatever. The women had on teensey-weensey little bottoms and no tops, and one of the guys was standing on the bow, and he slipped off his trunks and stood there a minute hanging hog, then jumped in the bay and swam around the boat. What a great country. I put down my binoculars and popped a Budweiser.

—Plum Island, by Nelson DeMille

Third-person limited invites the reader into the head of the “he/she” character, as in:

Richard Chapman presumed there would be a stripper at his brother Philip’s bachelor party. Perhaps if he had actually thought about it, he might even have expected two. Sure, in sitcoms the stripper always arrived alone, but he knew that in real life strippers often came in pairs. How else could there be a little pretend (or not pretend) girl-on-girl action on the living room carpet? Besides, he worked in mergers and acquisitions, he understood the exigencies of commerce as well as anyone: two strippers meant you could have two gentlemen squirming at once.

—The Guest Room, by Chris Bohjalian

“Get that light out of my face! And get behind the tape. All of you. Now.” Detective Jake Brogan pointed his own flashlight at the pack of reporters, its cold glow highlighting one news-greedy face after another in the October darkness. He recognized television. Radio. That kid from the paper. How the hell did they get here so fast? The whiffle of a chopper, one of theirs, hovered over the riverbank, its spotlights illuminating the unmistakable—another long night on the job. And a Monday-morning visit to a grieving family. If they could figure out who this victim was.

—The Other Woman, by Hank Phillippi Ryan

POV Rule #2

Choose your point of view character(s) carefully.

Generally speaking, your point-of-view character should be your protagonist. Readers want to be in the head of their favorite character, which, as we’ve seen, should be your protagonist. (Unless your protagonist would be more appealing to readers though the eyes of another character—as the arrogant Sherlock Holmes is more appealing as seen through the eyes of his friend Dr. Watson. But this is rare.)

Sometimes point of view is what distinguishes the story and sets it apart from its competition. Think of The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold, a heartbreaking thriller written from the point of view of Susie Salmon, a fourteen-year-old dead girl who was raped and murdered by a neighbor and now lives in heaven. Or Room by Emma Donoghue, written from the point of view of Jack, a five-year-old boy unknowingly held prisoner with his mother in a tiny space that constitutes their entire world. In Spencer Quinn’s best-selling Chet and Bernie mystery series, each novel is written from the point of view of Chet, the dog who aids the private eye in his investigations. In Garth Stein’s The Art of Racing in the Rain, the ailing mutt Enzo tells the story of his race-car driver human and a family torn apart by tragedy.

I know, I know, I hated the thought of reading stories from the points of view of dead girls and dying dogs, too, but I read all of these books and loved them, along with millions of other people. I fell in love with Susie Salmon and little Jack, although I admit I avoided their stories for the longest time because I knew that their stories would haunt me. And they do, to this day.

I fell in love with Chet and Enzo, too, and not just because I’m a dog person but because each canine voice was pitch perfect and the stories they told from their respective canine voices were compelling.

Point of view is problematic enough when you’re writing from an adult human’s point of view, when that’s what you are. Writing from the point of view of a little boy or a dead teenage girl is wicked difficult; only experienced storytellers who’ve mastered their craft should attempt this. If I had a dollar for every awful story I’ve read where the writer tried and failed—badly—to write from the point of view of an animal or an alien or an adolescent, I’d be on the next plane to Paris. So think twice before you try this at home.

“When I write from the point of view of a child or a young person, I am trying to tell the truth as an adult voice sometimes cannot. We are so often wrapped in the garment of trying to reassure ourselves that we are not afraid.”

—Michael Cadnum

POV Rule #3

If you choose first person, then you must use that POV alone throughout the story.

I know that you see this rule broken all the time—most notably by Gillian Flynn in her megahit Gone Girl—but trust me, you don’t want to go there, especially if this is your first story. You’ll seriously handicap your opportunity to sell your work if you use multiple first-person points of view. Agents and editors mistrust multiple first-person points of view for good reason: With all those different “I” characters, it’s difficult to keep track of which “I” is which.

This requires a very high level of craft to pull off properly. Don’t risk it. I’ve had a few clients who failed to sell their work until I made them aware of this point-of-view issue. They fixed the problem, and I sold their work.

POV Rule #4

If you choose third-person limited point of view, do not use more than six POVs per story. This is called multiple third-person limited POV.

We know that readers like to be in the head of the hero, so you need to stay in that hero’s point of view most of the time. That said, you may need to use other point-of-view characters; in a mystery, for example, the points of view often include that of the victim and the villain, as well as the sleuth protagonist. Some novels feature dual protagonists; for example, both Hank Phillippi Ryan and Julia Spencer-Fleming use his-and-hers POVs in their mystery series. And you find novels with ensemble casts where the POV switches from chapter to chapter among the principals; in William Kent Krueger’s Cork O’Connor novels, the author often includes chapters written from the point of view of Cork’s nearest and dearest, who have become as beloved in readers’ hearts as Cork himself. Whenever you change points of view, readers must shift their attention from the character they love—your heroine—to characters they don’t love quite so much or may even loathe. So the fewer POV characters in your story, the better, and never risk more than six points of view per book. Yes, I know you see this rule broken all the time, most notably by George R.R. Martin in A Game of Thrones. But he’s a master, and he knows how to break the rules (and we’ll see just how he does it under the heading Breaking the POV Rules).

POV Rule #5

When writing in third-person limited point of view, don’t jump from head to head.

You are not playing tennis here; you don’t want your readers snapping back and forth from one character’s head to another like they’re at Wimbledon. Not to mention that editors hate it. The general rule of thumb when writing multiple third-person limited point of view is to stick to one POV per scene. This will help you avoid “jumping head syndrome.”

POV Rule #6

Avoid using third-person-omniscient point of view.

Seriously. It should go without saying that you should not even think about using third-person-omniscient point of view, which is the author playing God and speaking directly to the reader, as is often seen in science fiction, fantasy, British mysteries, European fiction, nineteenth-century novels, and the like. Other writers—particularly those from the United Kingdom, Europe, and/or those originally published abroad—jump around from one character’s head to another in the same scene all the time and get away with it. American editors view omniscient point of view as hopelessly outdated, so if you are shopping your work to American publishers in today’s marketplace, don’t do it.

Breaking the POV Rules: A Game of Thrones

When Writers Digest publisher Phil Sexton first asked me to write this book on story openings, I was skeptical at first. How could I come up with 75,000 words on beginnings? Sure, I’d been doing the Scene One: First Ten Pages Boot Camps for Writers Digest successfully for a couple of years, but I still was not entirely convinced I could manage it.

And then I talked to a client of mine, a wonderfully talented novelist who writes historical fiction. She’d written an extraordinary story that I loved, but she’d used several points of view, far more than the allotted six points of view that we’ve talked about here. I knew that so many points of view would make it a lot harder—if not impossible—to sell. I told her that, but she told me that other writers had pulled it off, notably William Faulkner in his classic As I Lay Dying and George R.R. Martin in his blockbuster A Game of Thrones.

First things first: Faulkner.

Seriously.

Sure, he’s a genius, but you should know that whenever a writer invokes the “F” word, I tend to panic. And I’m not alone in that; most editors and agents would react the same way. (And I say that based on an informal, if admittedly anecdotal, survey of my colleagues.) I panic because there’s only one Faulkner, and he’s one of the most obtuse writers of the twentieth century. This does not bode well for my marketing plan for any project, much less historical fiction, which often errs on the far side of pedantic anyway.

And if you’re thinking, “What a Philistine,” well, hello, I’m an agent and my job is to sell my clients’ books. That said, I owed my client a sensible and thoughtful response. To that end, I reread the opening of As I Lay Dying, which confirmed my belief that this was a high-wire POV act only Faulkner could pull off successfully.

On the other hand, my client’s story opening provided an uneven and unclear reading experience because, among other things, her opening was written in multiple first-person points of view, and these point-of-view switches came too often and too quickly—around every five-hundred to one thousand words.

This muddled the story—and confused the reader. As an agent, I’ve found that it’s hard as hell to sell confusion. What resonates with readers today is clarity.

To be fair, I also reread the first fifty pages of A Game of Thrones (which in the mass-market edition runs about twenty thousand words). I’d always remembered Faulkner as a challenging read for the reasons discussed, but I didn’t remember any such issues with A Game of Thrones. And I was curious to see what my client was talking about regarding point of view in George R.R. Martin’s bestseller.

As I suspected, my memory served me well. The opening of A Game of Thrones is not a choppy reading experience. You can sum up the reason for this in one word: clarity. And it’s evident in the opening of A Game of Thrones. Martin uses multiple points of views, too, but he is very clever about it. Let’s take a look at how Martin manages to break the rules—brilliantly!—when he:

- sticks to third-person point of view (rather than first-person), which is much easier for the reader to follow, thanks to the blessing of pronouns and names

- spends a significant portion of time with each point-of-view character before he switches to another character’s point of view, which allows readers to invest more heavily in each character and that respective character’s thread of the story tapestry

- chooses very likable point-of-view characters in very challenging situations

- gives us great action, which keeps readers engaged even when they’d prefer to stay with the previous point-of-view character

- provides clear links from one point-of-view character in one chapter to the next point-of-view character in the next chapter.

A Game of Thrones Opening Breakdown

Let’s break down the beginning of this compelling epic fantasy, piece by piece, point of view by point of view:

Prologue

4,400 words

Will’s third-person-limited point of view

Will, young man of the Night’s Watch in the North, riding with Gared and Ser Waymar Royce, encounters the Others, and witnesses their attack on Royce (and his rising again!).

Bran

3,600 words

Bran’s third-person-limited point of view

Seven-year-old Bran sees his father Lord Ned Stark behead Gared (from the Prologue). Afterward they come across orphaned direwolf pups. (Beheadings and puppies! What’s not to like?)

Catelyn

2,800 words

Catelyn’s third-person-limited point of view

Catelyn, Bran’s mother and Ned Stark’s wife (from the Bran chapter), tells her husband that King Robert, who was married to her late sister, is coming from King’s Landing to pay them a visit. (This is not good news!)

Daenerys

4,600 words

Daenerys’s third-person-limited point of view

Thirteen-year-old exiled princess Daenerys meets Khal Drogo, the rich and powerful barbarian leader of a great army, to whom her cruel brother Viserys has betrothed her in the hope of returning to King’s Landing (from the Catelyn chapter) and recapturing his kingdom. (Thirteen! Married! Barbarian! Not to mention all that talk about dragons.)

Eddard

4,400 words

Lord Eddard “Ned” Stark’s third-person-limited point of view

Ned Stark of Winterfell entertains his former brother-in-law and comrade-in-arms King Robert from King’s Landing, who asks him to come south to be the Hand of the King, a dangerous death-wish of a job (referencing all previous chapters in one way or another). An offer he can’t refuse!

There are important lessons here. When you decide to take the risk of using multiple-first-person points of view or using more than six points of view even when writing in third-person limited point of view, know that you are making a decision that will undoubtedly complicate and hinder the selling of your work. If you make that risky choice, be sure that you amortize that risk by:

- choosing your point-of-view characters carefully, with an eye towards likability

- staying with each point-of-view character long enough for the reader to care about that character and invest in his or her particular perspective of the story

- putting those point-of-view characters in very challenging situations, emotionally, mentally, physically, spiritually, and/or otherwise

- giving the reader great action

- providing very clear links from one point-of-view scene/chapter/section to the next.

Stay with your likable point-of-view characters long enough for readers to get to know them, empathize with them, care about them, and/or invest in them. Plan your point-of-view switches carefully; don’t let them come too soon and too fast, as that makes for a choppy reading experience.

Readers always want to get back to their favorite character, so they have to be invested enough in that character to wade through the other characters’ point-of-view sections. This is why you need great action and clear links between points of view throughout so the reader understands why each moment is relevant to their favorite character’s story.

Martin does this by giving us a young man, a child, the child’s mother, the child’s father, and a thirteen-year-old princess bride—all characters with whom we can sympathize, all in challenging, dangerous, and even poignant situations. And he keeps us with each point-of-view character long enough for us to get to know him or her and care what happens to him or her and his or her family or community (if he or she has one). So we keep on reading, without resenting the author for making us spend time with new point-of-view characters.

“One of the most beautiful things about A Game of Thrones is it’s told from so many different points of view, and these characters can convince you that what they’re doing is right. But they’re only showing you a bit of the picture, and when you see it from another character’s point of view, you may switch allegiances.”

—Richard Madden

This is what you need to do. If you can manage this magic trick, then you can keep these points of view. But providing a compelling reading experience while presenting all of these different points of view is the work of a master magician and best left to the Penns and Tellers of the writing world. If this is your first rodeo, you might want to reconsider your strategy.

As we’ve seen, using a plethora of points of view and having such different voices from one point of view to another can make for a choppy reading experience. Martin avoids this by (1) using third-person point of view instead of first-person, and (2) using the same authorial voice even as he switches from one point of view character to another. That said, using a very distinct voice in your story can be one of its greatest achievements, but that means that you have to work extra hard to make the point-of-view shifts flow smoothly enough to carry the reader along.

“You could tell The Handmaid’s Tale from a male point of view. People have mistakenly felt that the women are oppressed, but power tends to organize itself in a pyramid. I could pick a male narrator from somewhere in that pyramid. It would be interesting.”

—Margaret Atwood

Character

“Character is king. There are probably fewer than six books every century remembered specifically for their plots. People remember characters.”

—Lee Child

Introducing your characters in the best light is one of the most important things you must accomplish in your beginning. All readers—agents, editors, publishers among them—are looking for the next Harry Potter, Jo March, Mr. Darcy, Lisbeth Salander, Easy Rawlins, Bridget Jones, T.S. Garp, Carrie Bradshaw, Hamlet and Viola and Puck, Cinderella, Hercule Poirot, Stephanie Plum, Rooster Cogburn, Jane Eyre, Tyrion Lannister, Scarlett O’Hara, James Bond, Scout Finch, Holden Caulfield, Katniss Everdeen, Jack Reacher, Celie and Pip and Alice, Old Yeller and Eeyore and Moby-Dick … well, you get the picture.

Readers want protagonists they can love and antagonists they can love to hate. They want their heroes and villains alike surrounded by a strong supporting cast of characters, a community that populates the plot and brings the story to life. Let’s take a look at the different ways that several beloved characters were introduced to readers.

Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charm as the Tarleton twins were. In her face were too sharply blended the delicate features of her mother, a Coast aristocrat of French descent, and the heavy ones of her florid Irish father. But it was an arresting face, pointed of chin, square of jaw. Her eyes were pale green without a touch of hazel, starred with bristly black lashes and slightly tilted at the ends. Above them, her thick black brows slanted upward, cutting a startling oblique line in her magnolia-white skin—that skin so prized by Southern women and so carefully guarded with bonnets, veils and mittens against hot Georgia suns.

—Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell

In the very first line of Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell establishes Scarlett O’Hara’s unique charm, born less of beauty than of vitality and determination. We see her flirting with the Tartleton twins, all Southern-belle coquette on the outside and all vitality and determination on the inside—the very qualities that that will see her through the burning of Atlanta and the love of Rhett Butler, among other challenges. Despite Scarlett’s many faults, she’s a survivor in a sea of lost causes, and readers love a survivor.

I was arrested in Eno’s Diner. At twelve o’clock. I was eating eggs and drinking coffee. A late breakfast, not lunch. I was wet and tired after a long walk in heavy rain. All the way from the highway to the edge of town.

—Killing Floor, by Lee Child

In creating Jack Reacher, Lee Child said he aimed to give readers a tough and uncompromising hero who “always wins.” In these opening lines of the first Reacher novel, we meet a guy so confident that he’s more concerned about his breakfast than about getting arrested. This is a guy we can root for, even if he doesn’t need us to.

“Bob Barnes says they got a dead body out on BLM land. He’s on line one.”

She might have knocked, but I didn’t hear it because I was watching the geese. I watch the geese a lot in the fall, when the days get shorter and the ice traces the rocky edges of Clear Creek.

—The Cold Dish, by Craig Johnson

In this first novel of his popular Walt Longmire series, Johnson introduces us to a complicated and philosophical sheriff whose eyes are on the horizon watching birds fly when they aren’t on the criminals in Absaroka County. We are intrigued and impressed. And do note that Johnson dropped a body in the very first line of the very first page. Now that’s how to open a mystery.

We called him Old Yeller. The name had a sort of double meaning. One part meant that his short hair was a dingy yellow, a color that we called “yeller” in those days. The other meant that when he opened his head, the sound he let out came closer to being a yell than a bark.

I remember like yesterday how he strayed in out of nowhere to our log cabin on Birdsong Creek. He made me so mad at first that I wanted to kill him. Then, later, when I had to kill him, it was like having to shoot some of my own folks. That’s how much I’d come to think of the big yeller dog.

—Old Yeller, by Fred Gipson

Anyone who’s read Old Yeller (or seen the Disney film based on the book) without crying is either made of stone or hates dogs (which, at least to dog lovers, is about the same thing). Here in the very opening lines of his classic story, Gipson makes us love this “dingy yellow” dog and tells us he’s going to die at the hands of the boy who loves him. And we love him more.

I could smell him—or rather the booze on his breath—before he even opened the door, but my sense of smell is pretty good, probably better than yours. The key scratched against the lock, finally found the slot. The door opened and in, with a little stumble, came Bernie Little, founder and part owner (his ex-wife, Leda, walked off with the rest) of the Little Detective Agency. I’d seen him look worse, but not often.

—Dog On It, by Spencer Quinn

Another bestseller, another dog, another opening. Only this time, the dog is our narrator, and he’s funny and smart and far superior in olfactory prowess to humans. We love that the canine Chet is the brains behind the Little Detective Agency—and, we suspect, the brawn as well—and we love Chet. We’ll go where his nose leads us. Woof, woof.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a most affectionate, indulgent father; and had, in consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of his house from a very early period. Her mother had died too long ago for her to have more than an indistinct remembrance of her caresses; and her place had been supplied by an excellent woman as governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

—Emma, by Jane Austen

Readers have been falling in love with Jane Austen’s characters for more than two hundred years. And here’s why. From the very first line of Emma, we like this pretty young woman of privilege because we know that if Austen says that there has thus far been “very little to distress or vex her,” that’s about to change. And we know that Emma will have to change, too—if she is to win the heart of the ever noble Mr. Knightley.

Once upon a time there was a young psychiatrist called Hector who was not very satisfied with himself.

Hector was not very satisfied with himself, even though he looked just like a real psychiatrist: he wore little round glasses that made him look intellectual; he knew how to listen to people sympathetically, saying “mmm”; he even had a little moustache, which he twirled when he was thinking very hard.

—Hector and the Search for Happiness, by François Lelord

A psychiatrist who is not very satisfied with himself? We’re hooked already because this is a shrink character we have rarely seen before, if ever—one that plays against the stereotypes built on the likes of Freud and Jung. We can picture Hector meeting with patients in his office, twirling his little moustache, worrying about his adequacies and inadequacies as a psychiatrist and as a man. And we are ready to tag along on his search for happiness, hoping for the best.

April 9, 1995

The Oregon Coast

If I have learned anything in this long life of mine, it is this: In love we find out who we want to be; in war we find out who we are. Today’s young people want to know everything about everyone. They think talking about a problem will solve it. I come from a quieter generation. We understand the value of forgetting, the lure of reinvention.

Lately, though, I find myself thinking about the war and my past, about the people I lost.

Lost.

—The Nightingale, by Kristin Hannah

In these opening lines of Hannah’s bestselling historical novel, we meet the narrator of this story, and I won’t say more than that, as revealing the identity of that narrator might prove a spoiler. In just these few lines, we suspect that the narrator has wisdom—learned the hard way—to impart and a good story to tell, perhaps even a heartbreaking story. And we want to hear it.

“Live through your characters. Let your characters live through you. Then you will love what you write, and others will, too.”

―Amanda Emerson

Your Protagonist

“The main question in drama, the way I was taught, is always: ‘What does the protagonist want?’ That’s what drama is. It comes down to that. It’s not about theme; it’s not about ideas; it’s not about setting but what the protagonist wants.”

―David Mamet

Your protagonist is the most important character in your story. All writers know this to be true, yet there are a number of issues that plague the protagonists in many of the story openings I see. Let’s take a look at these issues, one by one:

The protagonist comes across as unlikable.

Your hero needs to be likable, if not altogether lovable. I know this may fly in the face of [insert favorite anti-hero here], but even our favorite rebels and rogues have a certain charm. No reader wants to spend 350 pages or more with an unlikable character any more than you’d want to be stuck with someone unlikable on a long car ride. (Remember that painful cross-country drive with that moron from college? Do you really want to pay for a similar experience?) Your protagonist must be someone you wouldn’t mind being stuck with on a long car ride.

The protagonist is incompetent.

If your heroine isn’t particularly likable, she should at least be competent. Sherlock Holmes is an arrogant drug addict, but he’s so good at what he does that we forgive all just to be in the company of his genius.

The protagonist is passive.

Far too many protagonists are passive, rather than proactive. They don’t do anything, especially in the beginning of the story. We want to meet our protagonist in media res, that is, in the middle of doing something interesting. We can’t follow a character through a story if that character is not going anywhere.

The protagonist thinks too much.

Even heroes thinking great thoughts are not heroes unless they act. Heroes and heroines are, by definition, men and women of action. So have them step onto the stage of your story ready to act.

The protagonist is asleep.

Literally. Far too many stories begin with the heroine flat on her back, asleep, dreaming. This is no way to introduce your protagonist, no matter how good the dream is. Writers tell me all the time, “But it’s such a good dream/vision/whatever.” It doesn’t matter; readers know the difference between dreams and real life. They want to see the heroine in her real life, facing real obstacles and challenges, overcoming great odds and growing in mind, body, and spirit as a result.

The protagonist is alone doing nothing.

Perhaps the deadliest mistake a writer can make in a story opening is to present the heroine solo, alone on the story stage, doing nothing but dreaming or ruminating about her life, past, present, or future. Again, this is not the way to introduce your protagonist. In fact, you should be very discerning about scenes in which your hero is alone, not just in the beginning of your story but throughout it as well. If your hero is alone, he’d better be doing something darn interesting, like robbing a bank, building a bomb, or charming a snake.

The protagonist does not drive the action.

The heroine must not only act, but her action must drive the story. You’ve given her the leading role; let her take her part and run with it; let her play her part for all it’s worth. Note: This is one of the most common criticisms I hear from editors, that the protagonist does not drive the action of the story from beginning to end.

“The principle I always go on in writing a novel is to think of the characters in terms of actors in a play. I say to myself, if a big name were playing this part and if he found that after a strong first act he had practically nothing to do in the second act, he would walk out. Now, then, can I twist the story so as to give him plenty to do all the way through?”

—P.G. Wodehouse

Writers on Heroes, Heroines, and the Nature of Heroism

“Great heroes need great sorrows and burdens, or half their greatness goes unnoticed. It is all part of the fairy tale.”

―Peter S. Beagle

“Over time, it’s occurred to me that my protagonists all originate in some aspect of myself that I find myself questioning or feeling uncomfortable about.”

―Julia Glass

“You have to go out of your way as a suspense novelist to find situations where the protagonists are somewhat helpless and in real danger.

―Nelson DeMille

“With the crime novels, it’s delightful to have protagonists I can revisit in book after book. It’s like having a fictitious family.”

―John Banville

“Alpha heroes, even uberalpha heroes, still win readers’ hearts. I like a masterful hero myself, but I also enjoy the idea that sometimes the heroine can be in charge.”

―Emma Holly

“I had the feeling that focusing on objects and telling a story through them would make my protagonists different from those in Western novels—more real, more quintessentially of Istanbul.”

―Orhan Pamuk

“Characters stretching their legs in some calm haven generally don’t make for interesting protagonists.”

―Darin Strauss

“I read the Harry Potter books as I was writing my own books, and I love them, but I don’t think Harry was very much like I was as a kid. He’s always brave, and he’s perfect in a lot of ways.”

―Jeff Kinney

“I’m not at all interested in the brave who fight against the odds and win. I am interested in those who accept their lot, as that is what many people in the world are doing. They do their best in ghastly conditions.”

―Kazuo Ishiguro

“I’ve found in the past that the more closely I identify with the heroine, the less completely she emerges as a person. So from the first novel, I've been learning techniques to distance myself from the characters so that they are not me and I don’t try to protect them in ways that aren’t good for the story.”

―Beth Gutcheon

“I’m not nearly as outrageously brave as many of my rascals that I write. But I think the rascal spirit must reside in me somewhere.”

―Christopher Moore

“ [A] hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself.”

―Joseph Campbell

“My own heroes are the dreamers, those men and women who tried to make the world a better place than when they found it, whether in small ways or great ones. Some succeeded; some failed; most had mixed results ... but it is the effort that’s heroic, as I see it. Win or lose, I admire those who fight the good fight.”

—George R.R. Martin

“See, heroes never die. John Wayne isn’t dead, Elvis isn’t dead. Otherwise you don’t have a hero. You can’t kill a hero. That’s why I never let him get older.”

—Mickey Spillane

“There is perhaps no more rewarding romance heroine than she who is not expected to find love. The archetype comes in many disguises—the wallflower, the spinster, the governess, the single mom—but always with one sad claim: Love is not in her cards.”

―Sarah MacLean

“I got tired of books where the boy is a bit thick and the girl’s very clever. … Why can’t they be like the girls and boys that I know personally, who are equally funny and equally cross? Who get things equally wrong and are equally brave? And make the same mistakes?”

―Patrick Ness

“The life of the hero of the tale is, at the outset, overshadowed by bitter and hopeless struggles; one doubts that the little swineherd will ever be able to vanquish the awful Dragon with the twelve heads. And yet ... truth and courage prevail, and the youngest and most neglected son of the family, of the nation, of mankind, chops off all twelve heads of the Dragon, to the delight of our anxious hearts. This exultant victory, towards which the hero of the tale always strives, is the hope and trust of the peasantry and of all oppressed peoples. This hope helps them bear the burden of their destiny.”

—Gyula Illyés

“My favorite literary heroine is Jo March. It is hard to overstate what she meant to a small, plain girl called Jo, who had a hot temper and a burning ambition to be a writer.”

―J.K. Rowling

“I wanted to create a heroine that was flawed. I wanted her to be a real person. She’s selfish; she’s childish; she’s immature and because I’m doing a three-book arc, I really played that up in the first book. I wanted the reader to be annoyed with her at times.”

―Amber Benson

“Show me a hero, and I’ll write you a tragedy.”

―F. Scott Fitzgerald

“A good novel tells us the truth about its hero, but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author.”

―G.K. Chesterton

Your Antagonist

“You don’t really understand an antagonist until you understand why he’s a protagonist in his own version of the world.”

—John Rogers

If the protagonist is the most important character in your story, your antagonist should be willing to fight for the same distinction. In sports, playing a tough competitor helps you up your game, and your hero needs a powerful opponent to up his game as well. Too many antagonists are poorly drawn—cardboard villains who do not pose a threat worthy of your protagonist or your story. Create a complex and well-rounded villain; pit your protagonist against Hannibal Lecter, Medea, Count Dracula, Annie Wilkes, Norman Bates, Nurse Ratched, Mr. Dark, Lady Macbeth, Lord Voldemort, Cruella de Vil, or Iago. Give us a great villain, and put him to work bedeviling the protagonist right there in the beginning of your story.

Your antagonist is the second most important character in your story. All writers know this to be true, yet there are a number of issues that plague the antagonists in many of the story openings I see. Let’s take a look at these issues, one by one.

The antagonist comes across as one-dimensional.

Your villain needs to be a hero in his own mind, as we all are the stars of our own stories. You want a villain who is more than just bad; you want a villain who is a contradiction—charming but lethal, smart but neurotic, devoted to his dogs even as he murders his mother. Just as important, you want to paint the portrait of your antagonist with fine strokes of many colors, rather than broad strokes of black and white.

Think of the manipulative and malicious Cersei Lannister, whom we first see through her brother Tyrion’s eyes in A Game of Thrones.

His sister peered at him with the same expression of faint distaste she had worn since the day he was born.

Here we can see that Cersei feels superior to her brother and most everyone else, a disdain that foreshadows her unkindness toward him and others.

The antagonist is stupid.

If your antagonist is an idiot, he’s certainly not a worthy enough adversary for your hero. Many writers make the bad guys in their stories—especially in crime stories—so stupid that their capture seems inevitable, no challenge for the good guys at all. Better to make your antagonist smart, savvy, and sophisticated as Thomas Harris does in The Silence of the Lambs when he sends his heroine, Clarice Starling, to the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane to talk to the elegant cannibal.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter himself reclined on his bunk, perusing the Italian edition of Vogue. He held the loose pages in his right hand and put them beside him one by one with his left. Dr. Lecter has six fingers on his left hand.

This is a worldly man of taste and refinement, with a highly developed aesthetic and six fingers on his left hand. This Dickensian detail freaks us—and Clarice—out. We know it’s a sign of aberrations to come.

The antagonist drops out of the story too soon.

Unlike many writers’ unfortunate tendency to give their protagonists too little to do in the beginning of the story, many writers make the opposite mistake with their antagonists. The villains are very busy in the opening pages, deceiving their spouses and embezzling their employers and stabbing their rivals in their sleep, but then the villains may drop out of the story as the writers focus on the actions and reactions of the hero. This is fine; just don’t lose sight of your villain altogether. Remember: Your antagonist does not cease to exist when your hero takes center stage. In fact, the busier your villain is when he’s offstage, the better. Your antagonist should continue to plot against your protagonist throughout your story, just as the treacherous Iago does in Shakespeare’s Othello, putting his plan in motion and seeing it through.

Thus do I ever make my fool my purse;

For I mine own gained knowledge should profane

If I would time expend with such a snipe

But for my sport and profit. I hate the Moor,

And it is thought abroad that ’twixt my sheets

He’s done my office. I know not if ’t be true,

Yet I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety. He holds me well:

The better shall my purpose work on him.

Cassio’s a proper man: Let me see now,

To get his place and to plume up my will

In double knavery. How? How? Let’s see.

After some time, to abuse Othello’s ear

That he is too familiar with his wife.

He hath a person and a smooth dispose

To be suspected, framed to make women false.

The Moor is of a free and open nature

That thinks men honest that but seem to be so,

And will as tenderly be led by the nose

As asses are.

I have ’t. It is engendered. Hell and night

Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light.

The antagonist does not receive his just desserts.

The antagonist must throw down the gauntlet before the hero and fight hard and dirty, going for blood—but still earn eventual defeat. The shark must die in Peter Benchley’s Jaws, Hilly must eat Minny’s chocolate pie in Kathryn Stockett’s The Help, Buffalo Bill must be stopped before he kills again in Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs. From the very beginning, readers should see the storm clouds approaching and sense the drama of the thunder claps and lightning bolts to come. They should understand that this is the antagonist’s handiwork, even if, as in a murder mystery, they don’t know exactly who the villain is quite yet. They should be able to imagine that the time will come when the villain is defeated—even if they can’t imagine how the villain will meet his well-deserved end. And they should be just as determined that the antagonist will receive his just desserts as the protagonist is, just as we are determined that Annie Wilkes should receive her comeuppance right there in the opening pages of Stephen King’s Misery as we read about the protagonist, a writer named Paul.

He discovered three things almost simultaneously, about ten days after having emerged from the dark cloud. The first was that Annie Wilkes had a great deal of Novril (she had, in fact, a great many drugs of all kinds). The second was that he was hooked on Novril. The third was that Annie Wilkes was dangerously crazy.

Jump-Start

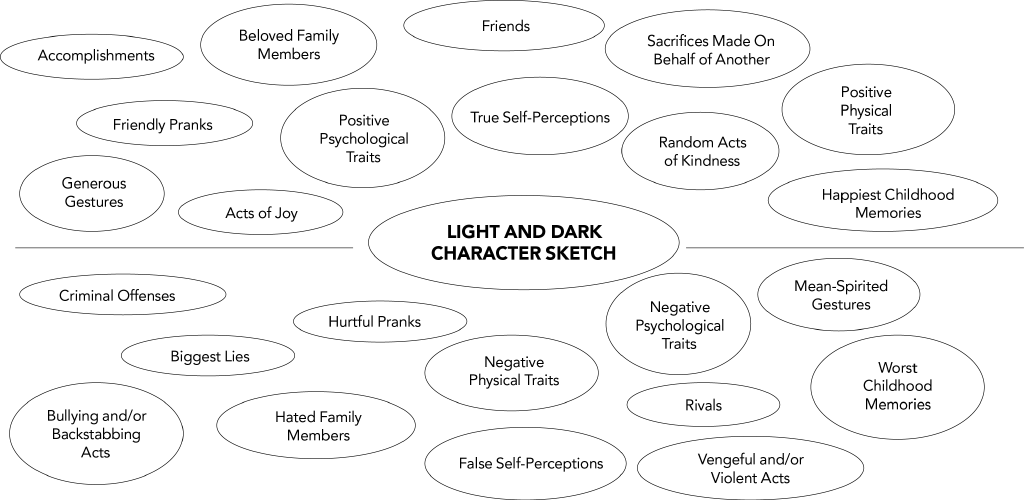

When you create your antagonists, you need to go looking for the light … and the dark. As we’ve seen, the most compelling villains are those made up of every shade of gray—from charcoal to cloud. To make sure your antagonists are well-developed, fill out the bubble chart below and use it to design the most worthy of adversaries.

Note: Of course, this will work for your other characters as well, including your protagonist.

Writers on Villains and Villainy

“The villain is the architect of the plot; make sure the villain is worthy of the hero.”

—Cara Black

“Nobody is a villain in their own story. We’re all the heroes of our own stories.”

—George R.R. Martin

“Evil is relative—and what I mean by that is that our villains are as complex, as deep, and as compelling as any of our heroes. Every antagonist in the DC Universe has a unique darkness, desire, and drive.”

—Geoff Johns

“People are much more complicated in real life, but my characters are as subtle and nuanced as I can make them. But if you say my characters are too black and white, you’ve missed the point. Villains are meant to be black-hearted in popular novels. If you say I have a grey-hearted villain, then I’ve failed.”

—Ken Follett

“The battleline between good and evil runs through the heart of every man.”

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

“I like not fair terms and a villain’s mind.”

—William Shakespeare

“More and more these days, what I find myself doing in my stories is making a representation of goodness and a representation of evil and then having those two run at each other full-speed, like a couple of peewee football players, to see what happens. Who stays standing? Whose helmet goes flying off?”

—George Saunders

“Who is to say who is the villain and who is the hero? Probably the dictionary.”

—Joss Whedon

“So once I thought of the villain with a sense of humor, I began to think of a name, and the name ‘The Joker’ immediately came to mind. There was the association with the Joker in the deck of cards, and I probably yelled literally, ‘Eureka!’ because I knew I had the name and the image at the same time.”

—Jerry Robinson

“The same energy of character which renders a man a daring villain would have rendered him useful in society, had that society been well organized.”

—Mary Wollstonecraft

“I firmly believe that a story is only as good as the villain.”

—Clive Barker

“Evil is not something superhuman; it’s something less than human.”

—Agatha Christie

“He that wrestles with us strengthens our nerves and sharpens our skill. Our antagonist is our helper.”

—Edmund Burke

“An excellent man, like precious metal, is in every way invariable; a villain, like the beams of a balance, is always varying, upwards and downwards.”

—John Locke

“I like to see the difference between good and evil as kind of like the foul line at a baseball game. It’s very thin, it’s made of something very flimsy like lime, and if you cross it, it really starts to blur where fair becomes foul and foul becomes fair.”

—Harlan Coben

“I mean, without the antagonist, there would be no story! It’d be like: ‘Once upon a time there was a girl who wanted to be loved, so she met a prince and got married and lived Happily Ever After, The End’? That’s not a story; that’s a bumper sticker.”

—Shannon Hale

“My theory of characterization is basically this: Put some dirt on a hero, and put some sunshine on the villain, one brushstroke of beauty on the villain.”

—Justin Cronin

“Evil doesn’t attack, it seduces.”

—Anne Perry

“As for an authentic villain, the real thing, the absolute, the artist, one rarely meets him even once in a lifetime. The ordinary bad hat is always in part a decent fellow.”

—Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette

“Only a writer who has the sense of evil can make goodness readable.”

—E.M. Forster

“I’ll tell you the secret. When you begin with a character, you want to begin by creating a villain.”

—Dorothy Allison

“It’s rather disconcerting to sit around a table participating in a critique of someone else’s work, only to realize the antagonist in the story is none other than yourself, and no one present thinks you’re a very likable character.”

—Michelle Richmond

“I don’t write about good and evil with this enormous dichotomy. I write about people. I write about people doing the kinds of things that people do.”

—Octavia E. Butler

“When something happens far back in the past, people often can’t recall exact details. Blame depends upon point of view. There may be a villain, but reality is frustrating because it’s often ambiguous.”

—Hallie Ephron

“Harvard was also a little bit of a villain in my first book, The Dante Club. I guess there might be a way to make Harvard more of a sympathetic presence, but it’s such a powerful institution that it more naturally lends itself toward not necessarily a negative but an obstructionist element in a story.”

—Matthew Pearl

“The characters that have greys are the more interesting characters. The hero who sometimes crosses the line and the villain who sometimes doesn’t are just much more interesting.”

—Geoff Johns

“No man is clever enough to know all the evil he does.”

—François de La Rochefoucauld

Supporting Cast

“No man is an island entire of itself; every man/is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. ... ”

—John Donne

No man is an island—and neither is a hero an island. The best protagonists are surrounded by people: family, friends, neighbors, rivals, enemies, frenemies, colleagues, acquaintances, strangers, and more. This supporting cast of characters is your best friend as a writer; build yourself a company of players, and use them to create conflict and heighten the drama. Your secondary characters give your protagonist someone to play with, for, and against—someone to seduce or strike, fight or fix, marry or murder.

As the late great actor Spencer Tracy once said, “Acting, to me, is always reacting.” Your protagonist needs to be reacting, acting, reacting, acting, reacting. Think of Spencer Tracy reacting to Katharine Hepburn, Kevin Spacey reacting to Robin Wright, Laurel reacting to Hardy, Tina Fey reacting to Amy Poehler, Tom Hanks reacting to Wilson, and Meryl Streep reacting to anything and anybody.

Unless your hero is stranded on Mars or cast away on a deserted island, your hero is part of a community, and that community is critical to the success of your story. Build that community, and as you do, consider the many functions supporting characters can provide:

- Mirror: Supporting characters can act as mirrors for protagonists, reflecting their own positive and negative traits right back at them. Think of sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, each serving as a mirror to the other, and as the author lets us know right there in the title of the novel.

- Moral Support: These are the characters who serve as shoulders to cry on for the protagonist. In Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw gets all kinds of moral support from her friends Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha.

- Ally: Every hero needs backup—the stronger and smarter, the better. Robert B. Parker gives his private detective Spenser the ultimate ally in Hawk, whose name says it all.

- Colleague: Your protagonist’s workplace is rife with possibility for secondary characters, and in some genres, such as police procedurals, a cast of colleagues is de rigueur. Think of Ed McBain, who set the standard with his colorful cops of the 87th Precinct, Walt Longmire’s associates in the Absaroka Sheriff’s Department in Craig Johnson’s Longmire series, and the tough and talented ladies of James Patterson’s Women’s Murder Club Series.

- Bad Influence: These characters are the unscrupulous pals who lead your protagonist down the wrong path. Think of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, who is persuaded to go to a land of perpetual recreation and amusement by the boy named Candlewick—a journey that results in Pinnochio’s transformation into a donkey.

- Mentor: If you’re looking for a mentor, look no farther than Homer’s The Odyssey, in which Telemachus receives assistance from Mentor, who is really the goddess Athena masquerading as a human, as the Greek gods were wont to do. Mentors run the gamut from Cinderella’s fairy godmother to James Bond’s M.

- Guru: Gurus are spiritual advisors who help keep their charges on the path of truth and beauty. Think Merlin, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and Yoda: “Powerful you have become; the dark side I sense in you.” Indeed.

- Corruptor: These characters are bad influences to the nth power—from Bud Fox’s boss Gordon Gekko in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street to war hero Michael Corleone’s entire family in Mario Puzo’s The Godfather.

- Wingman: Webster defines wingman as “a pilot or airplane that flies behind and outside the leader of a group of airplanes in order to provide support or protection—often used figuratively.” Or in reference to singles bars. Pop culture definitions aside, every guy needs a wingman, which is why Miles has his Jack in Rex Pickett’s Sideways (on which the acclaimed film was based), Sherlock Holmes has his Dr. Watson in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, and Frodo Baggins has his Samwise Gamgee in J.R.R.Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

- Lover: The protagonist’s love interest may play a smaller or larger role in your story, but in any case the lover gives readers a chance to see another side of your protagonist. In Robert B. Parker’s Spenser series, Spenser’s psychologist girlfriend, Susan Silverman, gives Spenser a kind of emotional ballast that he might not otherwise achieve, given his occupation and code of honor.

- Comic Relief: These are the supporting characters that make your protagonist and your readers laugh out loud, during good times and bad. Think of the Nurse, who provides comic relief in Shakespeare’s tragedy Romeo and Juliet, or Timon and Pumbaa, who lighten things up in Disney’s The Lion King.

Many of these roles are often combined, giving us wingmen who also serve as comic relief, lovers who also provide moral support, etc. Play with your supporting cast, and make them work on behalf of your protagonist and plot.

When Your Man Is an Island

If your hero is stranded on Mars, cast away on a deserted island, or otherwise alone in your story, you might want to rethink that. Otherwise, you will have your work cut out for you, as you’ll have to create what will prove the equivalent of a one-man show without the benefit of Matt Damon or Tom Hanks.

Sure, Andy Weir did it in The Martian (the novel on which the Matt Damon film was based), but the resourceful author had setting (Mars) and science (how the heck will the astronaut/engineer/botanist survive without food or water?) on his side. Weir also had a supporting cast, his hero Mark Watney’s fellow astronauts, engineers, and scientists, both up in space and down on Earth.

If you try this at home, you’ll have to be equally resourceful to pull it off.

“The only characters I ever don’t like are ones that leave no impression on me. And I don’t write characters that leave no impression on me.”

―Lauren DeStefano

Too Many Characters, Too Soon!

Don’t overcrowd your story opening with so many characters that your leading men and women get lost in the shuffle. In too many stories, the writer introduces far too many characters for the reader to keep track of, much less care about. Worse, most of these characters are usually not doing much; they’re just making an entrance and taking up space on the story’s stage.

People your story slowly, starting with your leads and your strongest supporting characters.

A good rule of thumb: no more than three to six characters in your opening pages. Begin with fewer characters, and give those characters a lot more to do.

Naming Names

Giving your characters good names can be a surprisingly tricky business. The right name gives readers an instant sense of who the character is, right from their introduction in your story.

But you’d be surprised at how many writers either don’t think about it at all or overthink it—all to the detriment of the story. Here are some basic guidelines you should consider when naming your characters:

- Find names that are easy to read, pronounce, and spell. Readers will stumble over excessively long, oddly spelled, and onerously enunciated names, and every time they do, they’ll fall right out of your story. If you’ve ever read Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, you surely stumbled over all those countless and confusing Russian names—from Arakcheyev to Zhilinsky.

- Mix it up. Do not use names that are too similar to other characters’ names in your story; avoid names of the same ethnicities, the same syllabic structures, the same sounds, and even the same first letters. No Watsons, Hudsons, and Watersons; no Dons, Jims, and Bobs; no Dawns, Ronnas, and Connors; no Claires, Chloes, and Catherines. When names are too much alike, readers may find themselves stopping to figure out who’s who all the time. Editors are as sensitive to this as readers, perhaps more so. Your character names should be as diverse as possible in every possible way; think of J.K. Rowling and her world of Hogwarts, populated with such perfectly and precisely named characters as Severus Snape, Rubeus Hagrid, Lord Voldemort, Ron Weasley, Draco Malfoy, Viktor Krum, Padma Patil, Albus Dumbledore, Nearly Headless Nick, Hermione Granger, and of course, the one and only Harry Potter.

- Choose a name in keeping with the sex, background, and temperament of the character. Margaret Mitchell famously called her Gone with the Wind heroine Patsy in early drafts of the story, a name we find laughable today. It’s difficult to imagine a wimp named Patsy playing the role of the survivor extraordinaire, Scarlett O’Hara.

Impromptu

If your story were a movie, who would you cast as your characters? Create a scrapbook of characters, either on paper in a standard scrapbook or in an electronic scrapbook. Who would play your hero? Your heroine? Your villain? Your supporting players? Make a page for each, and fill in their stats: birthdate, hometown, occupation, family, etc. Find photos of the actors and actresses you’d cast the roles in the film version of your story; seek out pictures of the clothes they’d wear, the homes they’d buy/rent, the vehicles in their driveways. Add maps, family trees, and any information that informs who and what they are. Don’t forget to add images that represent the light and dark of their natures as well. Turn to these scrapbooks to help you create well-rounded characters that readers will remember—and to remind or inspire you whenever you feel stuck while writing your narrative.

Setting

“I [have] spent my life on the road, waking in a pleasant or not so pleasant hotel, and setting off every morning after breakfast hoping to discover something new and repeatable, something worth writing about.”

—Paul Theroux

Setting is a critical but often underrated and underutilized element of a good story. One of the most common mistakes writers make in opening their stories is failing to embrace setting—or worse, ignoring it altogether. Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Eudora Welty said it best when she advised that setting is so paramount to story that changing the setting would change the story itself, because fiction is so dependent on a sense of place. As Welty said, “Place is the crossroads of circumstance, the proving ground of: ‘What happened? Who’s here? Who’s coming?’”

This is an elegant way of saying that you ignore setting at your own peril. Setting is one of the storyteller’s most valuable tools, one to be employed from the very beginning of your story. The trick is to make your setting as specific as possible; specificity is the key to compelling storytelling in general and compelling setting in particular.

Let’s take a look at writers who start straight off by grounding their stories in a very specific setting.

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

—A Farewell to Arms, by Ernest Hemingway

Here we get pulled right into the story by the rhythm of Hemingway’s prose and the uneasy beauty of the setting: a serene and lovely place, except for the marching troops, the rising dust, and the falling leaves. And we know we are in for a story about the inevitability of war and death, dust to dust, as it were.

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

—The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson

In this chilling opening, Shirley Jackson uses setting as a character to set the tone and warn the reader that Hill House is alive with wickedness, inviting the reader in for a walk through that house, alone.

When Sean Devine and Jimmy Marcus were kids, their fathers worked together at the Coleman Candy plant and carried the stench of warm chocolate back home with them. It became a permanent character of their clothes, the beds they slept in, the vinyl backs of their car seats. Sean’s kitchen smelled like a Fudgsicle, his bathroom like a Coleman Chew-Chew bar. By the time they were eleven, Sean and Jimmy had developed a hatred of sweets so total that they took their coffee black for the rest of their lives and never ate dessert.

—Mystic River, by Dennis Lehane

When the story is titled by its setting, as is Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River, we know before we even open the book that place is paramount. In this opening, we enter a working-class neighborhood where even the sweetness corrupts—and meet two boys who will navigate this neighborhood, for better or worse.

The night air was thick and damp. As I drove south along Lake Michigan, I could smell rotting alewives like a faint perfume on the heavy air. Little fires shone here and there from late-night barbecues in the park. On the water a host of green and red running lights showed people seeking relief from the sultry air. On shore traffic was heavy, the city moving restlessly, trying to breathe. It was July in Chicago.

—Indemnity Only, by Sara Paretsky

In this first of Paretsky’s celebrated V.I. Warshawski private-detective series, we feel the all-consuming heat of the city of Chicago, and we know the stage is set for violence.

It was my father who called the city the Mansion on the River.

He was talking about Charleston, South Carolina, and he was a native son, peacock proud of a town so pretty it makes your eyes ache with pleasure just to walk down its spellbinding, narrow streets. Charleston was my father’s ministry, his hobbyhorse, his quiet obsession, and the great love of his life. His bloodstream lit up my own with a passion for the city that I’ve never lost nor ever will. I’m Charleston-born, and -bred. The city’s two rivers, the Ashley and the Cooper, have flooded and shaped all the days of my life on this storied peninsula.

—South of Broad, by Pat Conroy

Pat Conroy made a career out of setting—whether it’s the Citadel, Melrose Island, Rome, or Charleston. In this opening, we meet a native son who’s been raised in the mythos of this Deep South gem, and we understand that gems can be as hard as they are lovely and myths are stories about fallen gods.

We didn’t always live on Mango Street. Before that we lived on Loomis on the third floor, and before that we lived on Keeler. Before Keeler it was Paulina, and before that I can’t remember. But what I remember most is moving a lot. Each time it seemed there’d be one more of us. By the time we got to Mango Street we were six—Mama, Papa, Carlos, Kiki, my sister Nenny and me.

The house on Mango Street is ours, and we don’t have to pay rent to anybody, or share the yard with the people downstairs, or be careful not to make too much noise, and there isn’t a landlord banging on the ceiling with a broom. But even so, it’s not the house we thought we’d get.

—The House on Mango Street, by Sandra Cisneros

The House on Mango Street is a coming-of-age classic, and we know from the charm and poignancy of this opening that here is an immigrant heroine who will not be defined by where she lives, even as she embraces the people who live there with her.

Each of these settings grounds its story in a very specific place. Whether it’s a European countryside torn apart by the Great War or a blue-collar Boston neighborhood reeking of chocolate, setting informs these stories from their opening lines. These stories could not be set anywhere else; setting is part and parcel of their plot and their power.

Specificity Counts

One of the most common failings of story openings is a lack of specificity, particularly when it comes to setting. Many writers set their scenes in places we’ve seen a million times before and miss a critical opportunity to reveal character, propel the plot, and explore themes in the process. There’s a reason movie and television producers hire location scouts to seek out interesting and unique locations for their productions; they know how important setting is to a good story, and they want to set their action against a compelling background that shows the audience something different and captivating on the screen.

When I read a writer’s story opening and realize the writer has not made the most of setting, I circle the nondescript nouns that clutter the prose. Three of the worst offenders: rooms, houses, streets. Those very nouns—rooms, houses, streets—are nondescript.

Let’s take a look at the many options you might use instead.

Room

Accommodation, alcove, attic, cabin, cave, cell, chamber, cubbyhole, cubicle, den, dorm, flat, flop, foyer, hall, hideout, hole, garret, joint, lean-to, lobby, lounge, lodging, nest, niche, office, quarter, setup, shed, shelter, space, studio, suite, turf, warren, vault

House

Abode, apartment, barrack, box, brownstone, building, bullpen, bungalow, cabin, cape cod, casa, castle, cave, chateau, co-op, commorancy, condo, condominium, cottage, coop, crash pad, digs, domicile, dump, dwelling, edifice, estate, flat, flophouse, habitation, haunt, headquarters, hole–in-the-wall, home, homestead, hut, joint, kennel, manor, mansion, pad, palace, pied-à-terre, pigpen, pigsty, quarters, ranch, residence, roost, sanctuary, shack, shanty, teepee, tent, trailer, villa

Street

Artery, avenue, back alley, boulevard, byway, causeway, court, cul-de-sac, dead end, drag, drive, esplanade, freeway, highway, lane, parkway, passage, pavement, pike, place, road, roadway, rotary, route, roundabout, row, stroll, terrace, thoroughfare, toll road, track, trail, turf, way

Jump-Start

Comb through your work, and circle all the nouns and other words and phrases related to your setting. Swap out the bland and generic ones for more descriptive terms that help paint your setting in fine detail. Don’t go overboard; you don’t want your story to read like a thesaurus, but do see how the right telling detail can bring your scenes to life.

Change Your Setting; Change Your Story

Ask yourself this: If I changed my setting, would it change my story? If not, you have some work to do in regard to your setting. Learn from the masters here, and check out the best writers in your genre as well to see how they handle setting. You need to get setting right, and if you do, your story opening will be all the more compelling for it.

The Direwolf Solution

If you are writing science fiction, fantasy, or historical fiction, you face an especially tough challenge in regard to setting. You must drop your readers into a whole new world—another place, another time, another dimension. Here, again, the key to creating a believable alternate environment is specificity.

Show us what makes your world special and unique. Be specific. Specificity can help you transcend the tropes that have become clichés:

- Don’t say castle; say “Castle Black.” Just naming the castle makes all of the difference, and naming it Castle Black gives readers a hint of the dark mission of the Night’s Watch.

- Don’t say city; say “King’s Landing.” Now the reader knows that this is a capitol city, a seat of power, where kings rise … and fall.

- Don’t say dog; say “direwolf.” George R.R. Martin borrowed the term dire wolf, which Webster defines as a “large extinct wolflike mammal (Canis dirus) known from Pleistocene deposits of North America,” to create his own magical species known as the direwolf, which beats the heck out of dog any day.

I use these examples from A Game of Thrones on purpose because Martin is always very specific—and he brings his world to life in living, breathing color—from dragons to direwolves. You must be, too.

“I wanted to write something in a voice that was unique to who I was. And I wanted something that was accessible to the person who works at Dunkin Donuts or who drives a bus, someone who comes home with their feet hurting like my father, someone who’s busy and has too many children, like my mother.”

—Sandra Cisneros

The Softer Side of Story

Now that we’ve outlined the rules of voice, point of view, character, and setting, you not only know how to avoid making the mistakes that could sabotage your efforts to sell your story; you’ve learned how to use these elements to give your story the subtleties, layers, and nuances that will take your work to the next level.

These elements are the meat on the bones of plot and the muscle of drama. When you master these elements, you imbue your writing with the sophistication and polish that, from the opening pages, can distinguish your work as being among the most well-crafted—and that can make the difference with editors, agents, and readers.

For you to showcase these finer points of storytelling to your best advantage, you need that solid muscle of drama beneath your story—the muscles of action, conflict, dialogue, and theme. In the next chapter, we’ll tackle the rules that can help you build the strong muscle you need to power up your story and keep it running at top speed.

“Writing has laws of perspective, of light and shade, just as painting does or music. If you are born knowing them, fine. If not, learn them. Then rearrange the rules to suit yourself.”

—Truman Capote