Chapter Seven

The Structure of Revelation

The End of the Beginning

“All writing is that structure of revelation.

There’s something you want to find out.

If you know everything up front in the beginning,

you really don’t need to read further

if there's nothing else to find out.”

—Walter Mosley

“Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

—Winston Churchill

Right before I started writing this section of the book, I spent some time with the extraordinary writer Robert Olen Butler. I met the Pulitzer-Prize-winning author at the St. Augustine Author-Mentor Novel Workshop, which is run by our mutual pal and writer Michael Neff. St. Augustine is a lovely beach town with great restaurants; over the course of a wonderful dinner—several hours of fine wine and delicious seafood at Catch 27—we talked about books, writing, and the art of teaching writers to write.

Butler had spent the day meeting with writers and critiquing the first five hundred words of their novels, short stories, and memoirs. I’d been helping these writers prepare for their meetings with Butler, and many had expressed dismay that Butler was only considering the first five hundred words of their stories.

“That’s not enough for him to know what my story is about,” they each told me, more or less in the same words each time.

“Not true,” I told them. “Five-hundred words fill two double-spaced manuscript pages, and that’s more than many editors, agents, and readers give you before passing or proceeding.”

They were unhappy to hear that. I told Butler, and he smiled. I smiled back. Because we both knew that if the first five hundred words aren’t right, then the next five hundred words won’t be either, nor will the five hundred words after that, and so on, for fifty- or seventy- or ninety-thousand words. The best stories are integrated units, from beginning to end. Achieving this integration is critical if your story is to hold together over some three-hundred pages.

For Butler, that integration requires knowing what your character wants and having that yearning—yearning is Butler’s favorite word—infuse the very DNA of your story. We drank more wine, and Butler expounded on his “unified field theory of yearning,” which is, plainly put, the idea that this integration is bound to the protagonist’s yearning. (Note: For more on his unified field theory of yearning, read Butler’s From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction, a must-have for all fiction writers.)

That’s why, to make sure you have a good beginning, you need to make sure that you have a good middle and a good end as well. This doesn’t mean that you need to know every detail of the work from page one to “The End,” but it does mean that you need a sense of where the story is going, what you are trying to say, and how you are going to say it.

And what your hero is yearning for.

“Yearning seems to be at the heart of what fiction as an art form is all about.… This notion of yearning has its reflection in one of the most fundamental craft points in fiction: plot. Because plot is simply yearning challenged and thwarted.”

—Robert Olen Butler

Story Structure 101

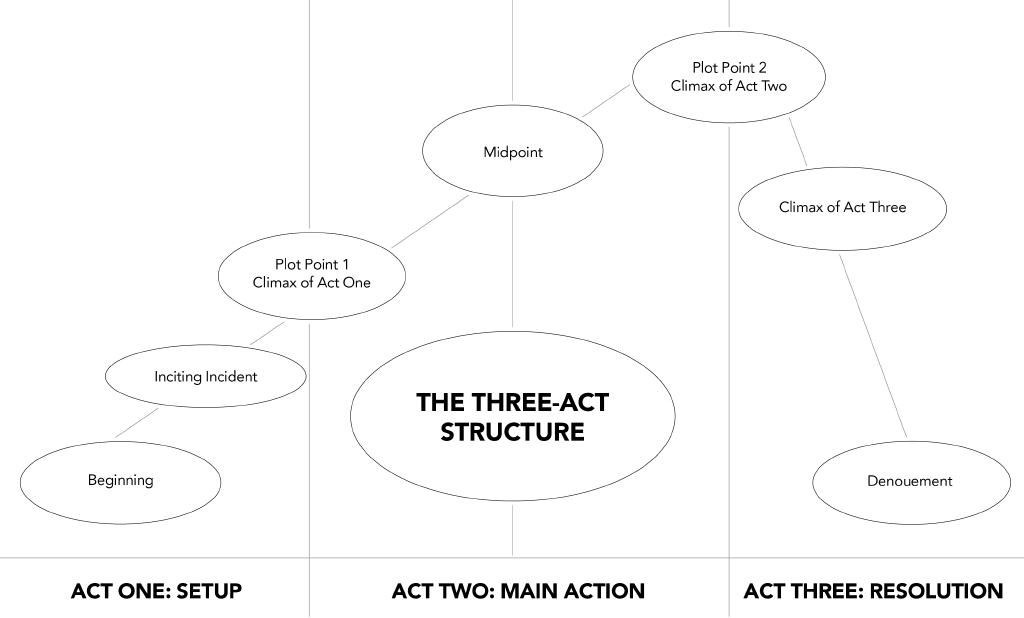

In chapter two, we examined the three-act structure in terms of a story’s beginning (act one), middle (act two), and end (act three). We also looked at the structure of your first scene. Now let’s look at the structure of your story in terms of plot points, not simply as events, but as, to paraphrase Butler, the challenges and thwarters of your character’s desires. This will allow you to break down Act One along with the rest of your story so that you can make sure that you build your story from your strong opening with equal strength and mastery to Plot Point One and right on to “The End.”

Refining the Three-Act Structure

Let’s start by refining our understanding of the three-act structure. Don’t just think of the three-act structure as the beginning, middle, and end; think of the three-act structure as the setup (act one), main action (act two), and resolution (act three). Let’s see how this looks for three classically structured stories that we all know and love.

Star Wars

Setup/Act One: Luke finds Princess Leia’s message in the droid but refuses to help until his aunt and uncle are killed by Stormtroopers.

Main Action/Act Two: Luke and his pals rescue Princess Leia and plan the attack on the Death Star.

Resolution/Act Three: Luke learns to trust the Force and destroys the Death Star.

What Luke wants (consciously): to become a Jedi Knight

What Luke wants (subconsciously): to find meaning in his life, to belong

Pride and Prejudice

Setup/Act One: Elizabeth Bennet meets the very rich, very eligible, and very proud Mr. Darcy—and hates him.

Main Action/Act Two: Mr. Darcy falls for Elizabeth despite her family and rank, but she rejects his badly delivered proposal in no uncertain terms.

Resolution/Act Three: Mr. Darcy redeems himself by saving the Bennet sisters’ reputation; Elizabeth realizes she has judged him too harshly, and they live happily ever after.

What Elizabeth wants (consciously): to marry a man of means whom she can respect and love

What Elizabeth wants (subconsciously): to merge with another without losing herself

The Maltese Falcon

Setup/Act One: Private detective Sam Spade’s partner Miles Archer is murdered while working on their new case for the mysterious Miss Wonderly.

Main Action/Act Two: Sam investigates the case, chases the Maltese Falcon, and falls for Wonderly a.k.a. Brigid O’Shaughnessy.

Resolution/Act Three: Sam Spade solves the case, confronts the murderer, and brings Brigid to justice.

What Sam Spade wants (consciously): to find Miles’s murderer

What Sam Spade wants (subconsciously): to be a man of honor

In chapter two, you broke down your first scene into its beginning, middle, and end. Now it’s time to break down your entire work into its beginning, middle, and end. Start by thinking in terms of setup, main action, and resolution, as shown in the aforementioned examples.

If you’re having trouble, consider these broad genre templates, which you can customize for your own story:

Love Story/Romance

Setup/Beginning: Boy meets girl.

Main Action/Middle: Boy loses girl.

Resolution/End: Boy gets girl back.

Protagonist’s Conscious Desire: To meet Mr./Ms. Right

Protagonist’s Subconscious Desire: To merge with his/her soulmate

Crime: Mystery/Thriller/Police Procedural

Setup/Beginning: Someone gets murdered.

Main Action/Middle: The cops/detective/amateur sleuth investigates the murder.

Resolution/End: The murderer is brought to justice.

Protagonist’s Conscious Desire: To solve the crime

Protagonist’s Subconscious Desire: To be an instrument of justice

Hero’s Journey: YA/Coming of Age/Self-Actualization

Setup/Beginning: The hero/heroine longs for adventure, and new acquaintances and events conspire to make that happen.

Main Action/Middle: With the help of the new friends and mentor, the hero/heroine undergoes a series of transformative experiences.

Resolution/End: Armed with this newfound knowledge and experience, the hero/heroine triumphs against overwhelming odds and is changed for the better.

Protagonist’s Conscious Desire: To be a grown-up

Protagonist’s Subconscious Desire: To live a meaningful life

Mission Story: SF/Fantasy/War Story/Military Thriller

Setup/Beginning: Our hero(es) is confronted with the challenge of the mission.

Main Action/Middle: Our hero(es) plans out, trains for, and undertakes the mission.

Resolution/End: Our hero(es) must go above and beyond to overcome the enemy, and the mission is won.

Protagonist’s Conscious Desire: To complete the mission

Protagonist’s Subconscious Desire: To champion a worthy cause

These templates can help you determine the setup, main action, and resolution of your own story, as well as the conscious and subconscious desires of your protagonist. Play around with these templates; adapt and combine them as you will. The important thing is to identify the yearnings of your hero and the broad strokes of the plot and work from there.

When you deconstruct a story this way, it’s easy to see why the beginning is so important. Not only must the beginning grab your readers by the throat and keep them reading, the beginning also needs to reveal your heroine’s desires and set up the rest of the story.

If the beginning doesn’t work, the rest of the story doesn’t work either. Act One blasts the story into the head space—and heart space—of the reader. Your opening scenes are the rocket boosters that thrust your story shuttle up and away.

The Point of Plot Points

The term plot point is one you’ve probably heard before. It’s just a fancy way of referring to the big scenes of your story, the ones that form the framework for the work itself. You frame your story with these scenes, just as you frame a house before you add the walls and the roof.

Without this framework, your story will not stand up but instead will fall in on itself, unable to support the weight of the characters and conflict with which you have burdened it. See the following chart for a graphic representation of this three-act structure, complete with plot points.

To fashion the most effective framework for your story, you simply need to build on the setup, main action, and resolution you’ve already designed.

Let’s look at those same three classic stories we examined before; only this time we’ll build their three-act structures to include the plot points.

Act One: Setup

Beginning: This is how the story opens, generally just before the Inciting Incident. (Or, in many stories, it can be the Inciting Incident itself.) In Star Wars, Princess Leia is running from the Stormtroopers. In Pride and Prejudice, news of the rich bachelor Mr. Bingley coming to town reaches Mrs. Bennet, and she redoubles her efforts to marry off her daughters well, starting with Jane and Elizabeth. The Maltese Falcon opens with Miss Wonderly arriving at Sam Spade’s office and hiring him to find her little sister.

Inciting Incident: This is the scene that jumpstarts the action of your story. For Star Wars, the Inciting Incident is when Princess Leia is captured and places the message and the plans in R2-D2. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth meets Mr. Darcy at a local ball, where he declines to dance with her, saying she is not handsome enough to tempt him. In The Maltese Falcon, Sam Spade’s partner Miles Archer is murdered while on Miss Wonderly’s case, and Sam is honor-bound to find his killer.

Plot Point #1: The first Plot Point is the big scene that takes the story in a new direction, setting up the action to come in Act Two. In Star Wars, Plot Point #1 is the murder of Luke’s aunt and uncle, which changes everything for him and convinces him to join Obi-Wan and become a Jedi Knight. In Pride and Prejudice, Plot Point #1 happens when Darcy persuades Bingley to abandon his courting of Elizabeth’s sister Jane and the Bingleys and Darcy leave Netherfield, taking the Bennet girls’ best prospects with them. In The Maltese Falcon, Plot Point #1 certainly takes the story in an entirely new direction, as it introduces the titular Maltese falcon and Joel Cairo offers Sam Spade five thousand dollars to find it. Note: Five grand was some serious money back in 1929. The search for this “MacGuffin of all MacGuffins” drives much of the action for the rest of the story.

Make a MacGuffin

MacGuffins are the objects, goals, events, or even characters in a story that help propel the plot, pitting characters in a struggle to capture it, control it, conceal it, or destroy it. Think of Bilbo’s ring in Lord of the Rings, the broomstick in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, or even Helen of Troy, “the face that launched a thousand ships” in The Iliad.

Do you have a MacGuffin in your story? If not, brainstorm ideas for MacGuffins. List the ways in which each possible MacGuffin might help you drive the action of your plot.

Act Two: Main Action

Midpoint: This is the big scene that you plant right in the middle of the story, building from Plot Point #1 to a significant reversal or twist. The Midpoint is a dangerous place in a story, as it’s the place where readers are most likely to quit on you and go watch HBO. That’s why you need something big to happen here, to keep readers engrossed in the plot and to avoid what the Hollywood people fear most—that telltale swishing in the seats that announce how bored the audience is at that most critical time in the viewing of a film. So make sure that you give your audience a scene to stay put for. In Star Wars, the Midpoint comes as Luke, Han et al attempt to rescue Princess Leia and get caught in the trash compactor from hell, the one with the terrible beastie lurking inside. In Pride and Prejudice, the Midpoint comes when Darcy proposes to Elizabeth in the least romantic way possible and in turn she rejects him in the most devastating terms. At the Midpoint in The Maltese Falcon, Spade passes out after being drugged and kicked in the head and comes to, determined to find out the real story behind the falcon.

Plot Point #2: This is the second big event in the story that takes it in a different direction, just as Plot Point #1 does. In Star Wars, Plot Point #2 happens when Obi-Wan takes on Darth Vader in a fight to the death, allowing Luke et al to escape unharmed. This has huge ramifications for everyone but especially our hero Luke, who loses his mentor just when he needs him the most. In Pride and Prejudice, Plot Point #2 has Lydia running off with the wicked Wickham, thereby threatening the all-important reputation of the Bennet girls, Elizabeth included, which could forever ruin their chances of making good marriages. In The Maltese Falcon, Plot Point #2 occurs when a bleeding man bursts into Spade’s office carrying a wrapped parcel containing the fabled Maltese falcon and promptly dies.

Act Three: Resolution

Climax: The Climax is the biggest event in the story, the one that resolves the main action of the story. In Star Wars, the Climax forces Luke to trust the Force and apply the wisdom and skill he learned from his beloved mentor Obi-Wan in order to destroy the Death Star. In Pride and Prejudice, the Climax comes when Elizabeth finds out that Mr. Darcy has saved the good Bennet name by arranging for Lydia and Wickham to be married, realizes she has misjudged him, and happily accepts his (second) proposal. In The Maltese Falcon, the Climax comes when Sam Spade confronts Brigid O’Shaughnessy, confesses his love for her, and turns her in to the police anyway.

Denouement: This is the wrap-up that ties up all the loose ends of the story and sets the scene for the sequel, should there be one in the works. In Star Wars, Luke comes home to a hero’s welcome, but we know that however sweet this victory, there will be more challenges ahead. The empire will strike back. In Pride and Prejudice, the Denouement describes the marriage of Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy, as well as that of Jane and Mr. Bingley and the ramifications of those happy unions throughout their circle of friends and family. In The Maltese Falcon, the Denouement sees Sam Spade back at the office, and when Iva shows up, he tells Effie to show his dead partner’s wife in to see him.

In Star Wars, Luke gets what he wants on both the conscious and subconscious levels: He destroys the Death Star, becomes a Jedi Knight, embraces the light side of the Force, and takes his place among the community of revolutionaries. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet gets what she wants on both the conscious and subconscious levels as well: She makes a successful marriage by anyone’s standards, including her mother’s, and even better, marries a man she truly loves and respects. She looks forward to a marriage of equals—at least as much as can be expected in the nineteenth century. In The Maltese Falcon, Sam Spade does get what he wants: He finds his partner’s killer and stays true to the code of honor that decrees that “when a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.” In the process, he loses the woman he loves.

When you’re planning the plot points of your story, keep the desires of your protagonist in mind. In the end, does your hero get what he wants? And does getting what he consciously wants also give him what he wants subconsciously or not?

These are the questions that you and your plot need to answer.

Jump-Start

Break down your story into its main plot points:

- Beginning

- Inciting Incident

- Plot Point #1

- Midpoint

- Plot Point #2

- Climax

- Denouement

Create one storyline in which your heroine gets what she wants on both the conscious and the subconscious levels and another in which she does not.

Ask yourself:

- Which story is more appealing?

- Which is more dramatic?

- Which is more emotionally satisfying for you?

- Which is more emotionally satisfying for your readers?

“I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere. I don’t praise plots as accurate representations of life but as ways to keep readers reading.”

—Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

Act One, Scene by Scene

The next step is to plot the first act of your story scene by scene, from the Beginning to Plot Point #1. That typically translates to between ten and fifteen scenes, but that can vary, depending on the length of the work and the nature of the story, as we’ll see in the following chart, which lists the Act One scenes for The Maltese Falcon.

| ACT ONE | |

|---|---|

Beginning | Miss Wonderly hires Sam Spade and Miles Archer to find her baby sister. |

Scene 2 | Spade gets a phone call, and he hails a cab. |

Inciting Incident | Spade finds the cops at the crime scene where Miles’s body has been found. |

Scene 4 | Spade calls his secretary, Effie, and asks her to tell Miles’s wife about his murder. |

Scene 5 | The cops drop by to interrogate Spade about Thursby, who has also been murdered. |

Scene 6 | Miles’s widow Iva is waiting for Spade at his office. Iva kisses him; he sends her home. |

Scene 7 | Effie tells Spade that Iva had just gotten home when she went to tell her about Miles. |

Scene 8 | Spade goes to the St. Mark, but Wonderly has checked out. |

Scene 9 | At the office, Effie tells Spade that Wonderly said to meet her at the Coronet. |

Scene 10 | Wonderly, a.k.a. Brigid O’Shaughnessy, tells Spade she’s scared and needs protection from the police. |

Scene 11 | Spade goes to visit Wise the attorney. |

Plot Point #1 | Joel Cairo offers Spade $5,000 to find the Maltese falcon. |

Now that you have a clearer view of your story’s three-act structure, you can drill down to the scene level and plot out your entire first act. In a 90,000-word novel or memoir, the first act is your first 90 pages, or 22,500 words. (In a 120-page screenplay, the first act is your first 30 pages.) Note: This is a flexible number; you should let your own story and the conventions of your genre have the last word.

You know your Beginning, Inciting Incident, and Plot Point #1. Now all you need to do is connect the dots with the scenes that fall in between these plot points. You can use the chart below for this purpose.

"A novel is a tricky thing to map."

—Reif Larsen

| ACT ONE | |

|---|---|

Beginning | |

Scene 2 | |

Scene 3 | |

Scene 4 | |

Inciting Incident | |

Scene 6 | |

Scene 7 | |

Scene 8 | |

Scene 9 | |

Scene 10 | |

Scene 11 | |

Scene 12 | |

Scene 13 | |

Scene 14 | |

Scene 15 | |

Plot Point #1 |

“There are only three kinds of scenes: negotiations, seductions, and fights.”

—Mike Nichols

The 90,000-Word Sweet Spot

Right now, when it comes to word count, it’s all about 90,000 words. Virtually every book I try to shop by a debut author that’s any longer than that—regardless of category—receives the same response from editors: “It’s just too long.” “No more than 90,000 words” seems to be the editor’s mantra these days. So I’ve asked several of my clients to shorten their novels and memoirs and am happy to say that we’ve won contracts when I shopped the shortened versions, often to the same editors who complained about the length of the original stories.

So when you plot your beginning, you need to plan with that 90,000-word sweet spot in mind. The following is a neat trick I came up with that’s proved useful for my clients and that may work for you as well.

Here’s how 90,000 words (which is 360 pages at 250 words per page) breaks down by act:

- Act One: 90 pages (22,500 words)

- Act Two: 180 pages (45,000 words)

- Act Three: 90 pages (22,500 words)

With that in mind, write out your basic storyline in major plot points only: Beginning, Inciting Incident, Plot Point #1, Midpoint, Plot Point #2, Climax, Denouement. Remember that these page counts and word counts are approximate and will vary according to the dictates of your story—but not too much. Too much variance might be a grand experiment, but odds are it’s a grand experiment that fails.

If you’ve already written your first draft and you’re over the 90,000-word sweet spot, then use the word counts by act as a general guideline, and cut anything you can cut to the word counts outlined above. Anything that does not get you from plot point to plot point must go.

If you haven’t yet finished your first draft, these act-by-act word counts will serve as your guidelines as you pound out the first draft.

Planting Subplots in Act One

Now that you’ve identified the major plot points of your story, you have some idea what your subplots will be. In Star Wars, the subplots are mostly relationship-based: Han and Luke, Luke and Princess Leia, Han and Princess Leia, Luke and Darth Vader, Obi-Wan and Darth Vader, Luke and Obi-Wan, and R2-D2 and C-3PO. In Pride and Prejudice, many of the subplots revolve around the other romantic entanglements besides Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy: all those sisters, all those subplots! In The Maltese Falcon, the subplots center around Sam’s relationships with women, namely Effie, Iva, and Brigid, his relationships with cops, lawyers, and the DA, and the relationships and rivalries among the various suspects, including Brigid, Gutman, Cairo, Wilmer, and Sam Spade himself.

For your subplots to prove effective, you need to introduce some (if not all of them) in Act One. This lends another layer of complexity to the challenge of writing a strong beginning to your story. We’ll take a harder look at introducing subplots in our genre-by-genre examination, as they vary according to category. But in the meantime, you should take note of the subplots that might help elevate your story to the next level. Start with your secondary characters since they often provide fertile ground for subplots. Here’s a list of the basic subplot types for you to consider for your story, as they relate to your protagonist:

- love interest(s)

- exes

- relationship with BFF

- relationship with family

- relationship with boss

- relationship with colleagues

- relationship with antagonist(s)

As you build your scenes in Act One, remember to weave in your subplot threads and introduce the characters who will people your subplots—from family and friends to suspects and strangers.

Pivot Your Plot Point #1

Coming up with a powerful scene for Plot Point #1 is very important. Often the genre may dictate the nature of the scene, many of which are often firsts: the first kiss in a romance, the first murder in a mystery, or the first skirmish in a war story. But even so, you should brainstorm ways to differentiate your first kiss, first murder, or first skirmish from those we’ve seen a million times before. Make your take on the conventional plot point stand out.

Act One Pointers

There are structural approaches for Act One that you may be tempted to try. Sometimes these approaches work and elevate your story; other times they fall flat.

Let’s examine these strategies one by one so that you may evaluate which might serve your story well and how you might make the most of each approach while avoiding their potential pitfalls.

The Prologue

“… what’s past is prologue ….”

—William Shakespeare

The prologue is ubiquitous. Why? It’s because writers mostly love them, even though readers mostly hate them. I know that you’re probably saying that you read stories with prologues all the time. Well, so do I. Some of my favorite novels begin with prologues, and I love them anyway. Sometimes I even write prologues but not that often because I know that the very word “prologue” is enough to alienate readers, editors, and agents.

For the record, readers often skip prologues, just as they skip introductions, forewords, and prefaces. I say this with great authority because once upon a time, I was an acquisitions editor, and I always let my authors write all the introductions, prefaces, and forewords they wanted for their nonfiction books—because I knew readers would never read them. Readers are smart; they know that whatever comes before chapter one in a nonfiction book is (often) just a self-indulgent rant, a nostalgic trip down memory lane, or otherwise nonsensical notes that have more to do with the ego that wrote the book than the book itself (the introductions to my own books notwithstanding, she said with a smile).

But both as an editor and as an agent, I have been much tougher on novelists and memoirists who wanted to begin their stories with prologues. Readers know they can open most nonfiction books to any page in the middle, end, or beginning and start reading; they can jump around to the content that interests them, skimming what they like and skipping what they don’t. But fiction and memoir are different. Here, the prologue should be a scene from the past that informs the story to come. For example: In a mystery, a prologue is often a murder scene that occurs years before the action of the story, a murder that comes back to haunt the characters in the present.

If the scene you have in mind for the prologue doesn’t inform the story to come, then you don’t need it. Ditch it. Too many writers have prologues that are just backstory and do not truly inform the story to come.

That’s why readers approach prologues with caution; they know that half the time the prologues are just a waste of space and that the real story doesn’t start until chapter one—after the prologue. They’ve been burned before, so many will simply skip it. Others will try it but will only keep reading if (1) it’s a compelling scene and (2) they can sense its relevance to the story to come. Remember the backstory caveat: What you needed to know to write the story is not what the reader needs to read it. (Never underestimate your readers. They’re as smart as you are, if not smarter.)

That said, begin your story with a prologue if you must. But if you do, write your prologue such that readers will actually read them. Here are some ways to help you do that.

“Avoid prologues. They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword.”

―Elmore Leonard

A Rose by Any Other Name Is Still a Prologue

The very word prologue is enough to put readers off. The best way to get around this problem is to simply not call your prologue a prologue. Call it something else. The easiest way is to use a time/place reference instead of the word “prologue,” e.g., “Paris, 1945," “Six Years Earlier,” or “3077 B.C.”

This time/place reference grounds the scene in the past and cues the readers that what happened at that time is important to the story they are about to read.

You can also employ any number of devices to indicate time, place, or other information you might need to communicate to the reader. Some of these devices may take the place of prologues altogether; others may serve as openers for prologues.

- News clippings can open your story, providing information and/or backstory in a more palatable manner that does not slow the story down (provided they are short enough), serving as context for your prologue or eliminating the need for one completely.

- Maps are particularly useful in SF/fantasy and historical fiction, not only helping to ground the reader in the time and place of your story before it even begins but also giving agents and editors notice that you have done your homework in terms of setting and/or world-building, critical aspects of these genres. If you do include a map, make sure that it’s a well-rendered one—amateur art screams, well, “Amateur!”

- Diary entries and letters can also deliver information and/or backstory in a compelling manner, provided that you actually deliver it in a compelling manner. These devices can become clichés in unskillful hands, so make sure that if you use one you do it in a creative and novel way. (See the following section on organizing principles.)

We’ll take a harder look at such devices as we explore the concept of organizing principles.

A Little Italic Goes a Long Way

When you write a prologue, use a different format to set it apart graphically from the rest of the text. Italics, breaks, and other graphic elements alert readers that this part of the text is special.

Note: If you use italics, try to keep the italics section to one page, two at the most. Reading italics can irritate the eyes, and readers may quit reading due to the strain, without really even knowing why.

The Organizing Principle

Your story may be a good candidate for an organizing principle. This is different from the plot; plot is what happens in your story, the list of scenes dramatizing the events of your story. You lay an organizing principle over the plot; it’s a way of organizing, sorting, and enhancing the themes, motifs, and imagery of your story. A well-chosen organizing principle can even serve as a strong differentiator for your story, helping to set it apart from the competition.

Think of it this way: Making a story is like baking a cake. You combine the essential ingredients—scenes—to create the batter of plot. Now you can choose to organize that batter in a number of ways: You can make cupcakes, sheet cake, a cake roll, or a double-layer cake. No matter which you choose, the batter remains the same; it’s the shape or vessel that holds the batter that changes, according to the organizing principle you choose.

Say you’re writing a love story. As we’ve seen, the basic plot for love stories is: Boy gets girl; boy loses girl; boy gets girl back (or not). Adding an organizing principle to the telling of a love story can help create a unique recasting of this same plot:

- In the New York Times best-selling rock 'n’ roll romance Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist, co-authors Rachel Cohn and David Levithan incorporate two organizing principles: (1) alternating his-and-her first-person points of view and (2) the metaphor of music. These two work together to introduce readers to Nick and Norah and give them a front-row seat at the ongoing concert of their relationship. Readers fall in love with these characters, the music, and the novel, thanks to these strongly conceived and executed organizing principles. And yes, this is the novel that inspired the swell film of the same name; read the book, watch the movie, and then compare notes.

- In the romantic comedy (500) Days of Summer, writers Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber tell the story of a couple’s relationship over the course of 500 days, numbering each scene. This organizing principle of numbered scenes permits the writers to jump around in the actual chronology of the plot without losing the audience. If you haven’t seen this film, you should see it, if only to admire its clever organizing principle in action, which turns a nonlinear narrative into very effective and even poignant storytelling. Moreover, this organizing principle gives the usual romantic-comedy treatment a very new twist, a twist that is largely responsible for its success.

- In the magical-realism classic Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments with Recipes, Romances, and Home Remedies, author Laura Esquivel lays the groundwork for her organizing principle right there in the subtitle, preparing readers for a journey of the heart like no other. She milks her food-as-life theme for all it’s worth, using recipes as chapter openers and infusing her prose with imagery of food, cooking, and fire. This story is a wonderful read, and all that imagery translates beautifully to the screen in the film adaption of the work.

- In the sad, sweet, hilarious, and ultimately irresistible PS, I Love You, author Cecelia Ahern uses an organizing principle as a plot device. The story is about a young widow named Holly whose beloved childhood sweetheart, Gerry, dies of a brain tumor. His last gift to her is a series of notes, one for each month of the year following his death. These notes form a blueprint of sorts, listing a number of goals for her to accomplish as she makes a new life without him. The notes are a recurring device throughout the story, driving the plot while also organizing it. (And, yes, they made a movie version of this one, too. See a pattern here?)

- In the blockbuster Gone Girl, which is at its heart a love story gone very, very wrong, Gillian Flynn tells the story of a married couple from alternating his-and-her first-person points of view, which, as we’ve seen with Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist, is an organizing principle in and of itself. Flynn also uses the device of a diary to tell the wife’s side of the story. Devices used as running elements throughout the entire story become organizing principles. In Gone Girl, the diary device helps remind readers whose point of view they’re reading at any given time (always a challenge with multiple first-person point of view), but also, in Flynn’s masterful hands, it becomes a slick sleight of hand that contributes to the story’s suspense. (If you haven’t read this book, you need to read it for craft alone—and no, seeing the movie is not the same thing; you need to see the words on the page to understand how she pulls off this magic trick.) Both of these strategies help make the story unique.

“All love stories are tales of beginnings. When we talk about falling in love, we go to the beginning to pinpoint the moment of freefall.”

—Meghan O'Rourke

Everyone loves a good organizing principle—agents, editors, and readers themselves. Organizing principles can also help you add layers of meaning, milk your metaphor, enhance the imagery, enhance the setting, and deepen the story’s themes. Most important, the best organizing principles run throughout your story from beginning to end, giving you the opportunity to set your story apart in agents’, editors’, and readers’ minds from the very first lines. This gives you a real edge when it comes time to shop your story to agents, editors, and publishers.

Getting Creative with Organizing Principles

When it comes to organizing principles, the possibilities are endless. Here’s an admittedly incomplete list of successful stories that employ a creative and clever organizing principle:

- Julie & Julia: 365 Days, 524 Recipes, 1 Tiny Apartment, by Julie Powell, a memoir in which Powell sets out to make all the recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking over the course of one year and blogs about it

- Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, by Cheryl Strayed, a memoir in which Strayed goes on a long journey—in travel memoirs there’s always a journey—through the wilderness to reclaim herself

- The Secret Life of Bees, by Sue Monk Kidd, a novel in which Kidd begins chapters with snippets from various texts on beekeeping (note that even the title speaks to the metaphor of her novel)

- My Horizontal Life, by Chelsea Handler, a memoir in which Handler reveals her sexual history, presenting her life as a series of one-night stands

- The Jane Austen Book Club, by Karen J. Fowler, a novel in which a group of women—and one man—gather monthly to discuss the novels of Jane Austen, whose themes, plot points, and preoccupations mirror the romantic lives of the characters

- And Then There Were None (a.k.a. Ten Little Indians), by Agatha Christie, a mystery in which the characters invited to a rich man’s island disappear one by one, a murderous organizing principle, even for this genre, but one so compelling that the book became an instant classic

- The World According to Garp, by John Irving, a best-selling literary novel in which the life of the hero, Garp, is told from his extraordinary conception to his messianic death, the organizing principle being the entire life cycle, as illuminated in the very last line (which I will leave to you to discover, if you have not yet read this moving story)

- Raiders of the Lost Ark, by George Lucas (story) and Lawrence Kasdan (screenplay), the remarkable adventure based on the Saturday serials of the thirties, forties, and fifties, in which the hero, Indiana Jones, faces one cliffhanger after another—from deadly spiders and slithering snakes to angry natives and nefarious Nazis

- Star Wars, by George Lucas, the epic space-opera film in which Luke Skywalker goes from farm boy to Jedi Knight in a transformation inspired by famed mythologist Joseph Campbell’s "hero’s journey”

- Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf, the luminous novel in which Clarissa Dalloway lives one day in her life, based on Aristotle’s assertion in Poetics that the action of a story should take place in twenty-four hours to achieve a unity of time

The best organizing principles are inextricably connected to a story’s plot, settings, and themes in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, starting right in the story’s opening. Let’s take a look at what that may actually look like on paper, with three wonderful stories whose organizing principles set them apart from the competition and proved a big part of their success.

Bridget Jones’s Diary, by Helen Fielding

In this hilarious international bestseller, each chapter opens with a diary entry in which the heroine recounts her day in terms of pounds gained, cigarettes smoked, and alcohol imbibed. Here’s the diary entry from its first chapter.

Sunday 1 January

129 lbs. (but post-Christmas), alcohol units 14 (but effectively covers 2 days as 4 hours of party was on New Year’s Day), cigarettes 22, calories 5424.

Food consumed today:

2 pkts Emmenthal cheese slices

14 cold new potatoes

2 Bloody Marys (count as food as contain Worcester sauce and tomatoes)

1⁄3 Ciabatta loaf with Brie

coriander leaves—1/2 packet

12 Milk Try (best to get rid of all Christmas confectionery in one go and make fresh start tomorrow)

13 cocktail sticks securing cheese and pineapple

Portion Una Alconbury’s turkey curry, peas and bananas

Portion Una Alconbury’s Raspberry Surprise made with Bourbon biscuits, tinned raspberries, eight gallons of whipped cream, decorated with glacé cherries and angelica.

The Know-It-All, by A.J. Jacobs

In this moving memoir, Jacobs weaves the story of his and his wife’s struggle with infertility with his obsessive goal of reading the entire Encyclopaedia Britannica—all 44 million words of it. Jacobs starts at the beginning, with the As, in this story organized alphabetically.

a-ak

That’s the first word in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. “A-ak.” Followed by this write-up: “Ancient East Asian music. See gagaku.”

That’s the entire article. Four words and then: “See gagaku.”

What a tease! Right at the start, the crafty Britannica has presented me with a dilemma. Should I flip ahead volume 6 and find out what's up with this gagaku, or should I stick with the plan, and move onto the second word in AA section? I decide to plow ahead with the AAs. Why ruin the suspense? If anyone brings up “a-ak” in conversation, I’ll just bluff. I’ll say, “Oh, I love gagaku!” or, “Did you hear that Madonna’s going to record an a-ak track on her next CD?”

Where’d You Go, Bernadette, by Maria Semple

This delightful novel uses all manner of devices for its organizing principle. In fact, I often recommend this novel to my clients and writing students because reading it is virtually a crash course in how to use devices in novel and fun ways. Semple ostensibly writes the novel from the first-person point of view of young heroine Bee, whose mother disappears right before Christmas. Semple obviously took the “if you’re writing from a first-person point of view, stick to that one point of view only for your entire story” very seriously (as well she should—and so should you). But this resourceful author was not about to let that limit her ability to write the story, so she used devices to bring other voices into the story. The following list of devices from this novel, which may or may not be complete, includes:

- report cards

- emails

- FBI official correspondence

- letters

- school notes

- grammar-school reports

- invitations

- signs

- blog posts

- book excerpts

- press releases

- articles

- Christmas poems

- transcripts

- IM messages

- police reports

- authorization requests

- presentations

- psychiatric examinations

- songs

- hymns

- faxes

- ship captain’s reports

- forensic reports

I kid you not. Let’s take a look at the first device she uses in the story, which appears in the first chapter:

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15

Galer Street School is a place where compassion, academics, and global connectitude join together to create civic-minded citizens of a sustainable and diverse planet.

Student: Bee Branch

Grade: Eight

Teacher: Levy

KEY

S Surpasses Excellence

A Achieves Excellence

W Working towards Excellence

Geometry S

Biology S

World Religion S

Music S

Creative Writing S

Ceramics S

Language Arts S

Expressive Movement S

COMMENTS: Bee is a pure delight. Her love of learning is infectious, as are her kindness and humor. Bee is unafraid to ask questions. Her goal is always deep understanding of a given topic, not merely getting a good grade. The other students look to Bee for help in their studies, and she is always quick to respond with a smile. Bee exhibits extraordinary concentration when working alone; when working in a group, she is a quiet and confident leader. Of special note is what an accomplished flutist Bee continues to be. The year is only a third over, but already I am mourning the day Bee graduates from Galer Street and heads out into the world. I understand she is applying to boarding schools back east. I envy the teachers who get to meet Bee for the first time, and to discover for themselves what a lovely young woman she is.

All of these examples reflect how entertaining and enlightening a good organizing principle can be. They add a fun and fierce element that can add a layer of complexity to your story, boost its appeal to readers, and set it apart from the competition. In short, I’ve found as an agent that a strong organizing principle can help sell projects that might otherwise not find a home in today’s tough marketplace—maybe yours.

Jump-Start

Read one of the stories I’ve used as a good example here. Identify the various organizing principles and devices used in that story. Do the same for your favorite stories. How do the writers pull it off? How might you pull it off in your story? Brainstorm a long list.

Beginnings by Genre

Every genre has its idiosyncrasies and conventions, and you need to understand them to ensure that your story opening hits the marks of the genre and avoids the clichés and tropes that will doom your efforts to publish your work. Let’s look at each genre in turn, and identify the dos and don’ts of each.

Women’s Fiction

“I say, ‘I write romance, women’s fiction, chick lit.’ I think it all fits very comfortably under the same umbrella. Basically, I write books for women—books about relationships: books that make you laugh and sometimes make you cry a little.”

—Susan Elizabeth Phillips

- Do give us a likable and resourceful heroine readers can relate to.

- Do give your heroine a yearning for something bigger than herself.

- Do focus your story on the relationships your heroine has with her parents, her children, her siblings, her friends, her colleagues, and her rivals—as well as her love interest(s).

- Do consider planning your story around weddings, funerals, reunions, anniversaries, holidays, baby showers, graduations, and other rite-of-passage events of women’s lives.

- Do choose a setting that readers would love to visit.

- Do tell your story in a strong voice.

- Do weave in women’s themes—the bigger, the better.

- Do use an organizing principle if you can.

- Do use devices, metaphor, and imagery to layer your work.

- Don’t use tired tropes like the unhappy housewife, the bitter divorcée, the evil ex, the evil in-laws, etc.

- Don’t open with your character alone, thinking.

- Don’t slow your story down with backstory or info dumping.

“I’ve been typed as historical fiction, historical women’s fiction, historical mystery, historical chick lit, historical romance—all for the same book.”

—Lauren Willig

Literary Fiction

“That’s what fiction is for. It’s for getting at the truth when the truth isn’t sufficient for the truth.”

—Tim O’Brien

- Do give us a protagonist with a yearning for something.

- Do thwart that yearning again and again.

- Do make something happen.

- Do give us well-rounded, complex, and complicated characters.

- Do steep your story in setting.

- Do tell your story in a strong voice.

- Do weave in theme—the bigger, the better.

- Do use an organizing principle if you can.

- Do use metaphor and imagery to layer your work.

- Do pay attention to the language.

- Don’t leave your characters alone too long doing nothing or just navel-gazing.

- Don’t sacrifice story for pretty words.

“… good fiction’s job [is] to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

—David Foster Wallace

Romance

“A romance novel focuses exclusively on two people falling in love. It can’t be about a woman caring for her aging mother or something like that. It can have that element, but it has to be primarily about the male-female relationship.”

—Kristin Hannah

- Do give us a hero that any self-respecting heroine or reader can fall in love with.

- Do give us a likable, attractive, and strong heroine readers can relate to.

- Do arrange for a meet cute we haven’t seen before.

- Do set your story in a romantic place.

- Do use an organizing principle if you can.

- Do give your hero and/or heroine a secret that will be revealed.

- Do make us believe that this couple must be together or they’ll be unhappy forever.

- Do surround your couple with family, friends, frenemies, and rivals.

- Don’t use tired tropes like evil exes, manipulative mothers-in-law, BFFs turned lovers, charming bad boys, student/teacher romances, amnesia plots, or the country-mouse/city-mouse theme.

“The lust and attraction are often a given in a romance novel—I want to dig into the elements of true friendship that form a foundation for a solid, gonna-last-forever romantic relationship.”

—Suzanne Brockmann

Crime Fiction

“Mysteries and thrillers are not the same things, though they are literary siblings. Roughly put, I would say the distinction is that mysteries emphasize motive and psychology, whereas thrillers rely more heavily on action and plot.”

—Jon Meacham

- Do give us a proactive protagonist who can drive the action, solve the crime, and save the day.

- Do ground your story in setting.

- Do give your amateur sleuth an interesting occupation.

- Do introduce your suspects in Act One.

- Do plant your clues and red herrings early and often.

- Do get out of the courtroom if you’re writing a legal thriller.

- Do surround your protagonist with a strong supporting cast.

- Do set your cozy in a community that readers will love.

- Do drop the first body as soon as possible, chapter one, if not page one.

- Don’t use tired tropes like alcoholic cops, stupid criminals, phone calls in the middle of the night, etc.

- Don’t let up on the conflict or the pacing, especially in a thriller.

“In suspense novels, even subplots about relationships have to have conflict.”

—Jeffery Deaver

Science Fiction

“To write good SF today ... you must push further and harder, reach down deeper into your own mind until you break through into the strange and terrible country wherein live your own dreams.”

—Gardner Dozois

- Do give us a protagonist worthy and able to save the universe.

- Do get the science right.

- Do get out of the spaceship.

- Do give us strong, well-drawn female characters who defy the space-babe stereotype.

- Do give us aliens worth reading about—no more tentacles, please.

- Don’t give us all-powerful computers.

- Don’t use tired tropes like warp drives, hyperdrives, interstellar empires/federations, pulse weapons, etc.

- Don’t overburden your story with endless explanations of the science.

- Don’t give us a deus ex machina ending.

- Do resolve the main action of the story, even if you’re planning on writing a series.

“If it has horses and swords in it, it’s a fantasy, unless it also has a rocketship in it, in which case it becomes science fiction. The only thing that’ll turn a story with a rocketship in it back into fantasy is the Holy Grail.”

—Debra Doyle

Fantasy

“Fantasy doesn’t have to be fantastic. American writers in particular find this much harder to grasp. You need to have your feet on the ground as much as your head in the clouds. The cute dragon that sits on your shoulder also craps all down your back, but this makes it more interesting because it gives it an added dimension.”

—Terry Pratchett

- Do give us a worthy, well-rounded—not perfect!—protagonist.

- Do build a world we haven’t seen a million times before—that is, not rehashed J.R.R. Tolkien or George R.R. Martin.

- Do consider creating a map of your world.

- Do give us strong, well-drawn female characters who defy the princess/warrior/witch stereotypes.

- Do surround your protagonist with a strong supporting cast.

- Do use names for people, places, and things that are easy to read and spell and won’t trip up the reader.

- Don’t open with dreams and visions.

- Don’t use tired tropes like faeries, dragons, elves, Dungeons & Dragons magic, telepathy, etc.

- Don’t overburden your opening with backstory and/or flowery description.

- Do resolve the main action of the story, even if you’re planning on writing a series.

“Fantasy is hardly an escape from reality. It’s a way of understanding it.”

―Lloyd Alexander

Horror

“[Horror fiction] shows us that the control we believe we have is purely illusory and that every moment we teeter on chaos and oblivion.”

—Clive Barker

- Do give us a brave and intelligent protagonist.

- Do give us a well-rounded villain who’s not just a one-trick psychotic pony.

- Do give us monsters we have not seen before.

- Do give us strong, well-drawn female characters who defy the weak and whiny stereotypes.

- Do give us settings we have not seen before.

- Do keep the suspense and the terror coming.

- Do use humor for comic relief.

- Don’t be gross just for the sake of being gross.

- Don’t use tired tropes like scary basements, noises in the attic, and multiple-personality disorder.

- Don’t overburden your reader with backstory and/or description.

“Any writer of horror needs to at least have a good, solid love of the genre. Also, good horror writers need to have a slightly twisted sense of humor. Without humor, horror just isn’t as good.”

—Alistair Cross

Historical Fiction

“It’s really important in any historical fiction, I think, to anchor the story in its time. And you do that by weaving in those details, by, believe it or not, by the plumbing.”

—Jacqueline Winspear

- Do get the history right.

- Do consider using maps, family trees, news clippings, and other devices to deliver information the reader needs.

- Do create a protagonist readers can admire and relate to despite the difference in time periods.

- Do give us strong, well-drawn female characters who defy the limitations placed on women at the time.

- Do write dialogue that evokes the time period but is still easy for modern readers to understand.

- Do use a prose style that evokes the era but is still accessible.

- Do show us something we haven’t seen before or didn’t know about the era and its people.

- Do render your setting so well that it becomes a character.

- Do people your story with real people and/or events based on or inspired by true events.

- Do tie your story to present-day anniversaries, holidays, etc., if you can.

- Do use themes that are as relevant today as they were then.

- Do incorporate a strong bridge to the present if you can.

- Don’t overburden your story with endless historical research and description.

“Concentrate your narrative energy on the point of change. This is especially important for historical fiction. When your character is new to a place or things alter around them, that’s the point to step back and fill in the details of their world.”

—Hilary Mantel

Young Adult/Children’s

“As Jane Austen might have put it: It is a truth universally acknowledged that young protagonists in search of adventure must ditch their parents.”

—Philip Pullman

- Do give us a likable and resourceful protagonist.

- Do make sure your teenagers sound like teenagers and your children sound like children.

- Do make something happen fast, or your readers will bail on your story.

- Do open with conflict, and keep the action coming.

- Do keep your protagonist on the move.

- Do play against gender stereotypes.

- Do weave in coming-of-age themes.

- Do surround your protagonist with a strong supporting multicultural cast.

- Do use names for people, places, and things that are easy to read and spell and won’t trip up the reader.

- Don’t use tired tropes like evil parents, playground bullies, lame teachers, dystopian settings, etc.

- Don’t overburden your opening with backstory and/or info dumping.

- Don’t underestimate your young readers.

“Children’s books are harder to write. It’s tougher to keep a child interested because a child doesn’t have the concentration of an adult. A child knows the television is in the next room. It’s tough to hold a child, but it’s a lovely thing to try to do.”

—Roald Dahl

Memoir

“I’m very detail-oriented. I think that’s why people enjoy my memoirs—because I tend to remember everything.”

—Jen Lancaster

- Do write your memoir in a strong voice.

- Do choose your timeframe carefully, and condense it as much as possible.

- Do be as hard on yourself—if not harder—as you are on the others you write about in your memoir.

- Do make sure that you dramatize your story and write it in fully realized scenes.

- Do ground your memoir in the settings of your life.

- Do use an organizing principle if you can.

- Do use devices, metaphor, and imagery to layer your work.

- Don’t open with your character alone, thinking.

- Don’t slow your reader down with backstory or info dumping.

“In the worst memoirs, you can feel the author justifying himself—forgiving himself—in every paragraph. In the best memoirs, the author is tougher on him- or herself than his or her readers will ever be.”

—Darin Strauss

Jump-Start

Run down the list of caveats for each genre, starting with your own. Which might apply to your story? What do you need to work on?

Also consider the dos and don’ts for the other genres, and identify which of those could be strengthening or sabotaging your own work.

The End of the Beginning

We’ve taken a hard look at your entire first act in this section, and now you’re ready to finish your story. When you do, you’ll need to rewrite, revise, refine, and polish, polish, polish your work, starting with the opening.

The opening is the part of your story that agents and editors usually ask for—the first ten or fifty or one-hundred pages. Whether or not they ask to see more depends on the strength of your submission.

In chapter eight, we’ll look at the best way to polish your work in preparation for approaching agents and editors and submitting pages to them for review—with an eye on publication.