CHAPTER 6

Strategies: Making the Right Choices

What happens when you have a coffee making system that’s selling like gangbusters because of its exclusive, patented features, but its patent is about to expire? And your competitors will soon be able to copy your product and invade your market.

Answer: You spend a lot of sleepless nights while you work tirelessly on assessing the possible approaches, the possible strategies for how to deal with the issue, perhaps the most important issue ever for the company.

And that’s what strategies are all about. They’re the options and choices we must make when deciding how to achieve our goals. Choose the right strategy and we have a clear path to success. Choose the wrong one, and we’ll quickly be checkmated.

Fortunately, while the stakes are high, we’ve already done much of the work for developing and selecting strategies since they flow from our efforts in the top half of the hourglass—from our SWOT, SCA, and key issue identification. Basically, we start by asking the right questions:

![]() What do we do well that the market would value?

What do we do well that the market would value?

![]() What unanswered needs exist in our market?

What unanswered needs exist in our market?

![]() What would it take to become the market leader in this market?

What would it take to become the market leader in this market?

There’s a lot to consider, but our SWOT and SCA will help us decide where we should focus our attention—the right mix of factors such as where to “play”—the region or geographic area; what product categories, customer segments, and distribution channels to consider; and how our strengths and advantages can enhance our ability to win (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1. WHAT CHOICES DO WE MAKE?

Aha Moments and Insights Inspire Strategies

To generate a list of possible strategies, we have several good approaches for you to pursue. We have found that many options originate with the aha moments we experience in the top of the hourglass. Those insights inspire novel ways of looking at a problem, and they can do the same for developing strategies.

Since we want a range of strategies to assess, we also can brainstorm to help ensure that we have both diversity and quantity. Brainstorming has been called a method for creating an idea explosion, a creativity bomb of unfiltered, unevaluated, uncensored possibilities. (See the sidebar for details on this approach.) The goal of all approaches is to generate a set of core strategies plus possible alternative approaches.

Before we look at how we cull through our options and narrow down and finalize our choices, let’s look at Keurig and its strategic challenge of facing patent expiration.

Confronting Patent Expiration

By 2008, the Keurig single-cup coffeemaker had started its meteoric rise in popularity. People were captivated by the simplicity, convenience, and quality: pop a K-Cup Pack into the brewer, push a button, and get a consistently high-quality cup of coffee in minutes. Despite the recession, the parent company Keurig Green Mountain was growing at an amazing 70 percent compound growth rate.

Scaling up to keep pace with the growth was itself a problem. “Our management team knew we would have to almost double our workforce in 18 months,” says former president Michelle Stacy, “which meant we would have to hire potentially 200 people within 12 months . . . and that meant interviewing six times as many people—three candidates for each role, and two rounds of interviews for each one. A total of 1,800 interviews. Looking at what it would take just to keep up with the hiring, we were stunned.”

But Keurig’s HR group figured out how many recruiters it would need, and streamlined the procedure to minimize the amount of time spent on the interviewing. “We thought we were so smart,” says Michelle with a laugh, “We were doing a great job hiring—we had the whole thing down. And then I walked in one day and found two people sitting in a broom closet. Somewhere in the process, we’d completely forgotten that if you hire that many people, they need a place to sit. We were out of space. Next thing I knew, our CEO asked us to develop a plan for a new corporate headquarters in the Boston area.”

Running out of room and hiring new employees, however, were not the problems that kept Michelle and her team awake at night. Even though the company was growing rapidly, there was a huge potential problem on the horizon. The patent on their exclusive single-cup brewing system would expire in 2012. The company needed to make sure that its sustainable competitive advantage was not reliant entirely on the patent. It needed strategies and competencies that would extend its SCA on multiple fronts.

“In 2008, we were very aware that this was coming at us,” Michelle says. “The choice of what we would do was one of the biggest decisions we would ever make. What strategies could we deploy to minimize the impact of losing our patent exclusivity? We laid out three options:

![]() What would happen if we did nothing?

What would happen if we did nothing?

![]() What would happen if we put a new brewing system in place under a different patent?

What would happen if we put a new brewing system in place under a different patent?

![]() What would happen if we brought in partners?

What would happen if we brought in partners?

Michelle and her team then went back to their situation assessment for guidance and their key insight came when they took a closer look at their business from the consumer’s perspective.

Many experts had been puzzled by Keurig’s success. Beginning as a tiny start-up, it wasn’t the first to market with a single-serving coffeemaker. Analysts struggled to explain why Keurig had done so much better, even when it was competing head-to-head with bigger, more powerful adversaries like Nestle’s Nespresso brand.

“When we looked at our business from the consumer’s point of view, it came down to two reasons,” says Michelle. “The first is that the American consumer wants to drink 10 to 12 ounces of coffee in one sitting. Most of the other machines, including the ones that were ahead of us in the market, were based on the European preference for six ounces. Six ounces of coffee is not enough for the U.S. consumer, and watering down a good six-ounce cup with four ounces of water to get to 10 ounces is not the right answer. Ours was the first system that delivered eight to 12 ounces of coffee that really tasted good.”

The second reason was that American consumers wanted to have a choice. “Every other system was ‘my machine—my coffee,’” Michelle explains. “Keurig Green Mountain was different. We established relationships with other coffee roasters, so consumers didn’t feel locked in. For us it was ‘our machine—our coffee plus all these other possibilities.’ Initially, we worked with several smaller brands. But consumers liked choice, so we decided expanding our partnering strategy was our best option.”

And the Keurig Green Mountain team members made the right choice. They found that the more variety they offered, the more consumers loved their system. Keurig Green Mountain eventually brokered partnership arrangements with Dunkin’ Donuts and Starbucks and many other coffee and beverage makers. It was Keurig’s pathway into mainstream acceptance, and it was one of the keys to sustaining growth after the patents expired.

“Extending ourselves through our partners created a network of coffee brands. We might have lost a little short-term profit, but we gained long-term profitability. Nevertheless, it was a tremendous risk,” Michelle says. “We were inviting the competition into our proprietary systems. You can imagine what it was like to sit across from our own Green Mountain Coffee brand manager and say, ‘By the way, we’re going to Starbucks next week, because we think we need the Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donut brands in the system.’ Those discussions were gut-wrenching, but the partnerships really were the right choice for the business.”

“All of those companies that came in as partners with us before we came off the patent stayed with us as partners after we came off the patent,” says Michelle. “And we never went over that cliff that so many expected.”

Winning Beyond Patents

The process of weighing these options and making such a momentous decision also prompted Michelle and her team to go back and reconsider what Keurig Green Mountain’s sustainable competitive advantage really was. If it wasn’t the patent, what was it? “We asked ourselves, ‘What did we have that nobody else can get to?’” she says, “and we realized that what we had was more than just being protected by patents. We had the collective know-how to make the system work. We knew our consumers. We knew who they were and what they wanted. We had a unique relationship with them. We owned the way the brewer functioned, how it heated, the algorithms that are in it to heat and then pressurize the water to deliver a great cup of coffee. We owned how to make the portion pack, and we owned the connection between the brewer and the pack. The knowledge of how to do that, and how to do it with ease, was really our sustainable competitive advantage.”

Keurig’s success in developing, assessing, and acting on strategic options over the years was evidenced by the phenomenal shareholder value it created. The company also received a vote of confidence when the Coca-Cola Company purchased 16 percent of the firm’s equity and signed a joint agreement for Keurig to sell many of Coke’s cold refreshment beverages in Keurig’s unique in-home/in-office cold beverage brewer.

Zeroing In on the Right Choices

Choosing the best strategy begins with having the right set of options to select from. But how do we know which strategy or set of strategies to select? Narrowing the list of options again involves asking a series of questions to see which approaches seem most likely to present a winning solution. For example, what conditions would have to be in place for us to be confident of this possibility? Are those conditions in place now, or could they be put in place? Do we have adequate facts and data to feel confident about the approach? Would the approach yield significant enough results to move us toward our goal?

As we go through these questions, we can further assess which factors are essential, or must-haves, and which are helpful but not indispensable.

Once we’ve assessed the value of our different options, then we have to gauge the degree of difficulty in carrying them out. In other words, what are the enablers and barriers to each option? For enablers, are they now in place or could they be created in a timely, affordable fashion? For barriers, what would be the degree of difficulty in eliminating or overcoming them? If the enablers are in place and the potential barriers can be quickly overcome, the choice is likely to be sound. If barriers exist and we’re unsure whether they can be surmounted, then further review and testing is necessary.

Once we’ve finalized our likely strategies, we ask some additional questions to confirm our selection. Can we link our strategies to particular goals? Do they leverage our sustainable competitive advantage(s)? When implemented would the strategies deliver results and impact to meet our goals and address our key issues?

At this time, we also make note of the strategies we considered, but discarded. These may prove useful in the future, especially if conditions change. These ideas not only form a group of options-in-waiting, but also help sharpen the ability to explain the chosen strategy to others. It is always important to have contingency strategies, a “plan B,” in the event our strategies don’t work or can’t be implemented.

Let’s see now how a midsized company approached its strategic choices as it viewed a market where demographics, trends, brand image, and consumer preferences all had started moving against it.

Dramatic Market Change Dictates Dramatic Strategic Shift

When a cosmetics and skin-care company that we’ll call BetterFace, Inc. considered its options to address the dramatic changes revealed in its situation assessment, it developed and discarded several alternative strategies before committing to four core strategies that would transform its business. As we’ll see, each of the accepted strategies was chosen by considering how well it matched BetterFace’s strengths, filled market needs, and could overcome barriers.

BetterFace made and marketed low- and moderate-priced cosmetics and skin-care products in chain drugstores and department stores. They also made upscale brands and store brands that sold through specialty channels, including home-shopping television, cosmetics-only shops, spas, beauty and skin-care salons, designer boutiques, and online.

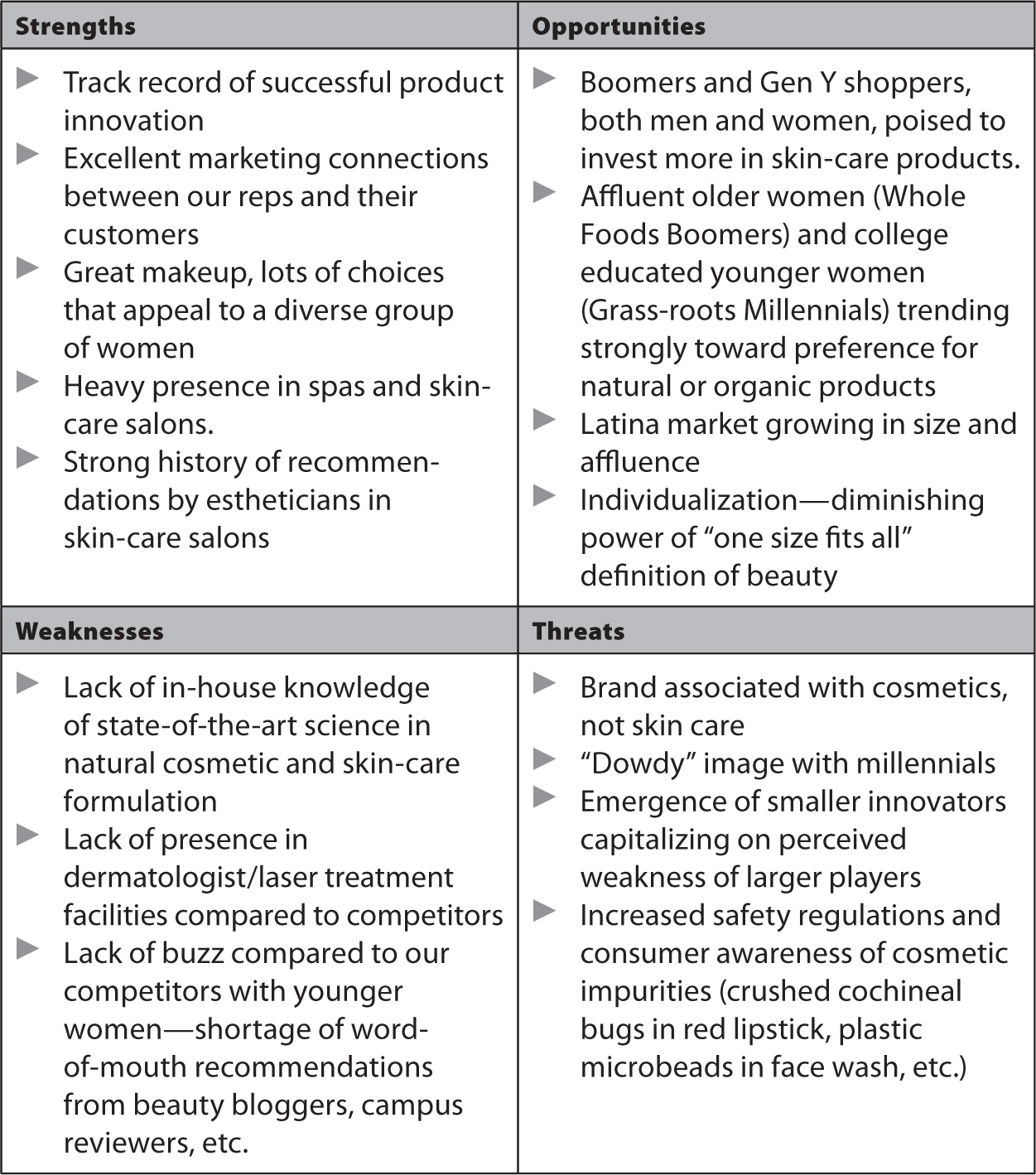

After an extensive situation assessment, it produced the SWOT shown in Table 6.1.

TABLE 6.1. BETTERFACE, INC.

For BetterFace, the greatest urgency was the need to pivot in response to rapidly changing market conditions. Boomer and Gen Y women, who comprise the core of its spa and home shopping market clientele, were shifting away from purchasing eye, cheek, and lip color, and instead were investing in skin-care products that hold off the appearance of aging. Unfortunately, BetterFace lacked a strong positive image with millennials—young women who could offset the anticipated losses among older women. To them, BetterFace made products for their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers.

Perhaps worse, BetterFace may have trouble hanging onto that core older generation, since its skin-care line has long taken a back seat to its brightly colored, higher-profit lines of lipsticks, eye shadows, and blushers. BetterFace has been known as a company that is skin deep.

It has a great reputation as a maker of a broad range of quality cosmetics that disguise or cover up flaws, wrinkles, and blemishes. It is not known as a maker of healthy, good-for-you products that make women look and feel beautiful from the inside out, nor does it have a particularly strong reputation for antiaging products. During the situation assessment, BetterFace confirmed this from survey research, but it is also echoed in the SWOT by the difference between its relative strength among estheticians in skin-care and beauty salons and its very low profile among clinicians in dermatological offices.

Strategies—No Longer Skin Deep

For BetterFace, the key takeaway from the analysis in the upper half of the hourglass is the imperative to escape the negative consequences of its “skin deep” reputation. To do so, it will have to greatly expand its skin-care line and cultivate a much stronger reputation as skin-care experts. Because the market is fragmenting by age, by ethnicity, and by skin type, it also needs to leverage its capacity for product innovation to develop product lines that appeal specifically to particular market segments: millennials, Latinas, and Asians.

In response, BetterFace produced the following vision statement: BetterFace: We love the skin you’re in.

It set goals that included the following marketplace targets:

![]() Grow skin-care net sales by 10 percent per year for the next three years.

Grow skin-care net sales by 10 percent per year for the next three years.

![]() Grow millennial market share by 5 percent per year for the next three years.

Grow millennial market share by 5 percent per year for the next three years.

![]() Grow Latina market share by 4 percent per year for the next three years.

Grow Latina market share by 4 percent per year for the next three years.

The question was how best to proceed. To reach those goals, BetterFace adopted a number of strategies in direct response to both marketplace opportunities and to serious threats:

![]() Strategy 1: Develop enhanced skin-care capability; expand skin-care offerings. This strategy, addressing a SWOT weakness, could be implemented either by rapid development of this capability in-house, or by acquisition of another company with skin-care expertise.

Strategy 1: Develop enhanced skin-care capability; expand skin-care offerings. This strategy, addressing a SWOT weakness, could be implemented either by rapid development of this capability in-house, or by acquisition of another company with skin-care expertise.

![]() Strategy 2: Launch organic skin-care line with natural ingredients. This strategy is dependent on the implementation of strategy 1. With organically sourced ingredients and recyclable packaging, it has the potential to span the generation gap, appealing both to “Whole Foods Boomers,” and “Grass-roots Millennials.” This strategy also addresses a SWOT weakness.

Strategy 2: Launch organic skin-care line with natural ingredients. This strategy is dependent on the implementation of strategy 1. With organically sourced ingredients and recyclable packaging, it has the potential to span the generation gap, appealing both to “Whole Foods Boomers,” and “Grass-roots Millennials.” This strategy also addresses a SWOT weakness.

![]() Strategy 3: Launch Latina cosmetics and skin-care line. This strategy would require development of a strong presence in Spanish language media, but also presents the future possibility of international sales in Central and South America. Given the traditional strong family ties in Latino families, promotion for this strategy is expected to stress the connection between mothers and daughters, both using the new line, but with products tailored specifically for each age group. The SWOT identifies the growing and increasingly affluent Latina market as an opportunity.

Strategy 3: Launch Latina cosmetics and skin-care line. This strategy would require development of a strong presence in Spanish language media, but also presents the future possibility of international sales in Central and South America. Given the traditional strong family ties in Latino families, promotion for this strategy is expected to stress the connection between mothers and daughters, both using the new line, but with products tailored specifically for each age group. The SWOT identifies the growing and increasingly affluent Latina market as an opportunity.

![]() Strategy 4: Launch millennial promotional campaign. This strategy would utilize social media to reintroduce BetterFace to younger women. It would also entail working through college-level social and professional organizations, which are predominantly female (sororities, nursing schools, elementary education programs) to distribute sample products and discount coupons. To implement this strategy, outsourcing would be needed to secure social media expertise.

Strategy 4: Launch millennial promotional campaign. This strategy would utilize social media to reintroduce BetterFace to younger women. It would also entail working through college-level social and professional organizations, which are predominantly female (sororities, nursing schools, elementary education programs) to distribute sample products and discount coupons. To implement this strategy, outsourcing would be needed to secure social media expertise.

Focus on the Vital Few

Also important to consider are the approaches rejected by BetterFace. The first was the “stay the course” option, which would have entailed minimal to moderate refinements to its business plan. If analysis in the top half of the hourglass had not shown such dramatic changes, this default approach of business as usual with some tweaks and adjustments might have been an option. But the SWOT made it clear that greater changes were essential.

Also rejected was the development of a Boomer men’s brand to parallel the aging skin-care line being developed for women. Men’s face-care products in general follow women’s trends; they do not precede them or even run concurrent with them. Once BetterFace had successfully launched its FreshFace brand for women, it would take another look at adding a men’s line.

A strategy to launch a separate millennial line also was deferred. After much discussion, BetterFace felt that adding another new line would overtax internal capabilities. So too was the option to launch a brand appealing specifically to Asian women. The market potential was not considered large enough, except on the West Coast. But the option would be revisited in the future if more new demographic information justified it.

Chapter Summary

![]() The daunting prospect of making a choice, deciding on the right strategies to pursue to achieve our goals, is made easy by the work done at the top of the hourglass.

The daunting prospect of making a choice, deciding on the right strategies to pursue to achieve our goals, is made easy by the work done at the top of the hourglass.

![]() Many strategic options flow directly from the insights and aha moments already experienced.

Many strategic options flow directly from the insights and aha moments already experienced.

![]() Our SWOT and SCA further guide our assessment and selection process since focus on our strengths and abilities to overcome weaknesses and barriers inform our choices.

Our SWOT and SCA further guide our assessment and selection process since focus on our strengths and abilities to overcome weaknesses and barriers inform our choices.

![]() Developing a robust list of options ensures comprehensive thinking, helps secure team alignment, and also provides contingency options for the future.

Developing a robust list of options ensures comprehensive thinking, helps secure team alignment, and also provides contingency options for the future.

Chapter 6 Exercises

What Choices Do We Make?

Mastering TTW Choices

Strategies are about choices. They answer the questions: Where do we play? and How do we win? They are the means to an end. Strategies need to be significant, have major impact, and be comprehensive enough to achieve the goal.

Start by asking:

![]() How do we determine our best set of options? How do we develop strategic alternatives, and how do we know which to select?

How do we determine our best set of options? How do we develop strategic alternatives, and how do we know which to select?

![]() What do we do well that the market might value?

What do we do well that the market might value?

![]() What would it take to be the next Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Walmart in this space? Where do we focus our efforts on the 10 percent of strategies that will deliver 90 percent of the wins? (See A. G. Lafley, R. Martin, J. W. Rivkin, and N. Siggelow, “Bringing Science to the Art of Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, September 2012.)

What would it take to be the next Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Walmart in this space? Where do we focus our efforts on the 10 percent of strategies that will deliver 90 percent of the wins? (See A. G. Lafley, R. Martin, J. W. Rivkin, and N. Siggelow, “Bringing Science to the Art of Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, September 2012.)

Exercise: Identifying Strategic Options

(Can be done at individual or group level)

1. Paying close attention to our implications and governing statements, brainstorm the strategic options: where to play (consider geographies, product categories, customer segments, channels we can add, market value) and how to win (consider our strengths and SCAs).

2. Create a list of statements—consolidate into four to six using the following criteria:

a. Leverage strengths

b. Addresses marketplace opportunities

c. Linkage to vision, governing statements, and goals

d. Capability

e. Customer/consumer demand

3. What are the conditions for success? What would have to be true for me to be confident in this possibility? (Example: Top two customers would have to support us, or consumers would trade up to a higher price point.)

4. For each strategic option that you are considering you will need to assess what is potentially getting in the way of the option becoming a strategic choice.

5. Have a conversation with other stakeholders to clarify and gain alignment.

The deliverable is a draft of strategic priorities.

You need to develop three different levels of strategies: core, alternative, and contingent. Your core strategy is what you will recommend based on the analysis in the top of the hourglass. Alternative strategies were actively considered, but ultimately rejected in favor of the core strategy. They are important because even though conditions are not right for them at this time, they may become your core strategies in the future. Your contingency strategy is your plan B. This backup plan is essential, in case the initial core strategies don’t work or become unavailable.

Organizational Assessment

Use the following table below as a checklist for identifying TTW principles and practices. This will help you to better understand where you and your team need to focus your energies. To get an idea where you believe your organization stands, read through each statement and jot down a rating:

Review individual items. Look for items on which you scored lower (3 and below) and think about the following questions:

![]() What do I believe is driving the score?

What do I believe is driving the score?

![]() What do I need to stop, start, or continue doing?

What do I need to stop, start, or continue doing?