CHAPTER 3

What It Takes to Win

What makes for a winning team in business? A charismatic manager who inspires her team members? A superstar who can outperform everyone? An all-consuming desire to win? Or is it luck and chance—everything coming together just right for victory? All are factors, but they’re not the real key.

When Michelle Stacy was given responsibility for restructuring the 500-person global professional sales group for Oral-B, the iconic dental products company, she found an organization that had lots of star performers who were eager, enthusiastic, and dedicated. But there also was virtually no consistency in strategic priorities and tactics across the globe. The commanding lead that Oral-B enjoyed in selling its products—manual and power toothbrushes, toothpastes, mouthwashes, and dental floss—and gaining patient recommendations from dentists and dental hygienists was being eroded by the very aggressive actions of Sonicare and Colgate.

Talent and persistence weren’t going to be enough to win in the future. The Oral-B professional sales group (SG) had to learn how to act differently and think to win. So Michelle’s first order of business was to introduce the thinking necessary to develop a strategic plan that would guide the organization to future success. She led her team through a structured approach for making decisions, a thinking process that aligned the organization and enabled its members to embrace major changes.

As we’ll see later in this chapter, by using TTW, the Oral-B professional SG moved from a struggling collection of talented individuals to a coherent, coordinated team with a long-term vision and detailed action plan for success.

Principles + Process

So how do we move from knowing the right principles for winning to putting those principles to work? Understanding the principles is important. Creating a mindset that acknowledges and embraces them is requisite. But Think to Win calls for principles plus a process. The strength and power of TTW flow from melding the five principles into an orderly, analytical process.

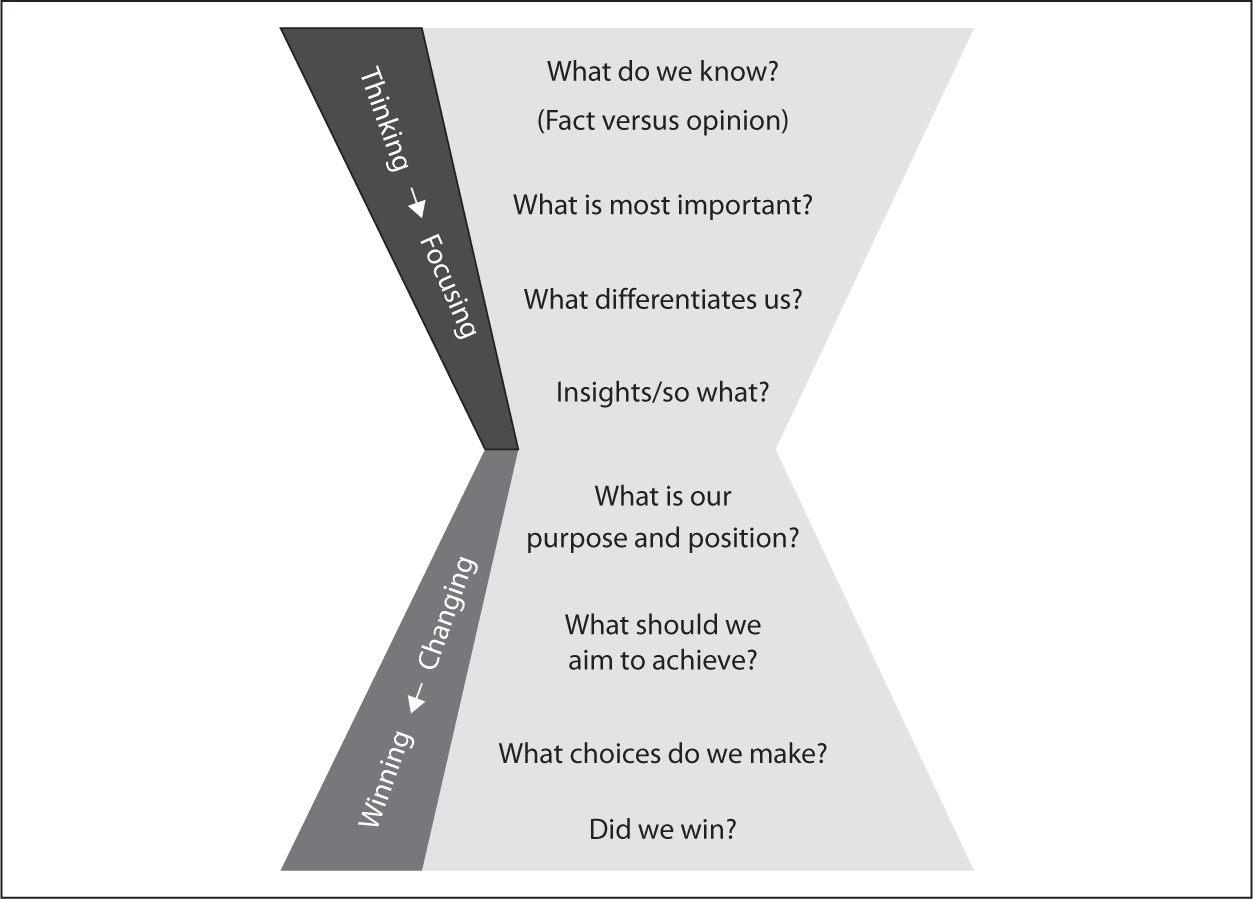

To visualize the process, we use an hourglass (see Figure 3.1) that expresses many aspects of TTW. The hourglass is a clear signal that timeliness is a critical factor in our TTW approach. But it’s also much more, providing an overview of the entire process that we’ll look at briefly now.

FIGURE 3.1. HOURGLASS REPRESENTATION OF TTW.

The top half of our hourglass acts as a funnel of information. As the hourglass narrows, the questions become more specific and more focused. With each question, we concentrate and strengthen our knowledge and understanding. This is convergent thinking. In other words, a large amount of factual data is compressed into relevant parcels that can be analyzed and dissected further. We analyze, sort, and sift, and then we reanalyze, resort, and reorganize.

As we look at the hourglass (see Figure 3.1), the first thing we notice is the wide opening at the top. Through this opening, we start identifying and processing what we know about our issue, challenge, or problem. We’ll be guided in deciding what facts to consider and what data to process by something called an umbrella statement. This is a simple statement that starts to frame our issue or problem by telling us such things as its scope and most impactful aspects.

We get additional guidance with our frameworks, which are tools that help us place data into buckets. They’re an important part of the discipline and structure. We provide a blueprint for creating customized frameworks to handle specific needs as well as offering several existing formats that have been proven to be broadly successful over time. We want our fact base and data gathering to be robust, but we don’t want to be paralyzed by an overload of data. And our frameworks keep everything manageable. (For details on frameworks and other tools, look at the exercises at the end of this chapter.)

As we answer the questions, we add meaning and significance to important facts and jettison less critical information. We converge on what really matters and look for insights that will have implications for how we should proceed. At this stage, we aren’t looking for detailed, quantified conclusions. We want a short list of observations and understandings—key issues—that tell us where the data are pointing.

With this key issues list, we move from convergent to divergent thinking. The list provides the basis for goal setting, which then goes through a series of steps that takes the TTW process to its action phase. The bottom half of the hourglass is where we address our issues, set our objectives and goals, identify possible strategies and alternative courses of actions, make choices from among them, identify initiatives—actions for implementing strategies—and determine how we will measure our success. When we reach the bottom of the hourglass, we have key messages that summarize what we know, what we’re going to do, and what the impact will be.

This is just a brief overview of the TTW process flow, which is further outlined in Figure 3.2. So don’t worry if terms and concepts aren’t crystal clear. We come back to them and provide more details and illustrations in each chapter. And as we move through the chapters, the simplicity and power of each step in this TTW process is likely to surprise you.

FIGURE 3.2. TTW PROCESS FLOW.

Umbrella Statements

Let’s look now at the first question we ask at the start of the TTW process: What are we trying to solve? What’s our issue? We call the answer to this question our umbrella statement. And it’s critically important to make this statement precise, concise, and something agreed to by everyone involved.

Top executive Gary Cohen says this sounds easy; but it’s not: “Throughout my career, I’ve worked on iconic consumer brands, including Gillette, Oral-B, Playtex, Hawaiian Tropic, and Timex. In each of these environments, getting people to actually agree on the situation [the umbrella statement] sounds so simple. But it’s one of the biggest barriers companies have in making the right choices. A lot of the issues that need to get solved are not at the 30,000 foot level; they are not ‘where-do-I-take-this-company’ issues. They are ‘what-choices-do-I-make-day-to-day? issues.” Yet in Gary’s experience, too many individuals, teams, or even executive committees will construct broad, encompassing umbrella statements that make it impossible to formulate actionable plans.

In our experience, there are often no efforts made to create an umbrella statement. People are so eager to get to a solution that they overlook the definition phase of the process. Or they assume that everyone has the same understanding and definition of the issue so there’s no need to discuss it. Yet whenever we work with teams or groups within companies and go around the table asking each person to give his or her view of the issue, there is never consensus or anything remotely close to common agreement.

So umbrella statements are essential. They don’t have to cover an entire company or involve macro issues. Rather they have to be directly applicable to a specific issue and the specific group that’s involved with it. As the beverage maker Keurig was gearing up to enter the home-brewed coffee market, its engineering team had to ensure that there was an adequate supply of single-serving brew cups. So it developed this concise, compelling statement:

The beverage system is projected to grow significantly over the next few years. Continuous supply of K-Cups is critical to the brewing system’s success. We need to develop a packaging equipment supply chain strategy to ensure highly reliable, efficient, and cost-effective equipment is available for our brewing partners.

Gary says that another common problem is the failure to reach agreement on the umbrella statement. Without this alignment, any approach that emerges from the process will be doomed to failure.

How clearly we define our umbrella statement goes a long way toward determining how successful we will be in addressing it. To unleash the power of TTW, our first task is to answer several challenging questions:

![]() What defines the issue?

What defines the issue?

![]() Why are we dealing with our issue? What happens if we don’t?

Why are we dealing with our issue? What happens if we don’t?

![]() Who is involved with this issue? Who is “under the umbrella” with us? Why is this issue important to them? Can we get their buy-in and align them on our umbrella statement?

Who is involved with this issue? Who is “under the umbrella” with us? Why is this issue important to them? Can we get their buy-in and align them on our umbrella statement?

When working with members of groups, we spend a lot of time urging them to gain agreement on the umbrella statement. Collective commitment is very powerful. We work and rework the umbrella statement, honing the concept, weighing the words carefully, building and reinforcing agreement among participants as we go. Securing alignment—getting people on the same page at the start—saves more time and conflict than any other single step in TTW.

This doesn’t mean that it’s easy to get everyone to agree. In our workshops, we give each participant a piece of flip chart paper. We ask participants to write down their thoughts; then we put all the papers up on the wall. Some participants try to boil the ocean. They identify a problem that is too vast; it’s outside their area of control and far too big to solve. Others think too small—they choose insignificant, marginal issues that would have no real impact. Gaining consensus on the true issue is a challenge when working with these extremes.

Strong Statements—Convey Tension and Underscore Conviction

Let’s see what’s involved in preparing an effective umbrella statement. We have found that they contain several attributes:

![]() Clear. An umbrella statement should be succinct, not long and detailed. Two or three clear, declarative sentences should be written so people can understand the statement without further explanation.

Clear. An umbrella statement should be succinct, not long and detailed. Two or three clear, declarative sentences should be written so people can understand the statement without further explanation.

![]() Focused. An umbrella statement must be specific to the organization and to the situation at hand. An effective statement focuses on a single problem.

Focused. An umbrella statement must be specific to the organization and to the situation at hand. An effective statement focuses on a single problem.

![]() Compelling. An umbrella statement should identify the importance of an issue and the consequences of not taking action. The statement should convey tension and underscore the conviction that something must be done.

Compelling. An umbrella statement should identify the importance of an issue and the consequences of not taking action. The statement should convey tension and underscore the conviction that something must be done.

What are some characteristics of ineffective umbrella statements? They are vague and sound as if they could apply to anyone in any organization at any time. If statements don’t create a compelling sense of urgency, they tend to be ignored.

Here are examples of effective and ineffective statements. The first involves a magazine publisher whose subscription levels have been declining. As a result, ad revenues also have dropped:

Ineffective. Our circulation has been declining because our subscribers have been moving to e-readers and phone apps.

Effective. The landscape we operate in has changed dramatically. We are challenged by competitors who provide information to our consumers for free. Not only are we losing customers, but we are in danger of becoming obsolete.

Now consider the issue facing the design team for a personal care products company. Its largest retail customer (30 percent of the business) has demanded improved display packaging for the holiday season. It has to be easy for store clerks to handle and very eye-catching to consumers in the aisles. Only one vendor will be chosen:

Ineffective. Merchandising is an important part of our business. We do not have the optimal solution in place for our product lines. Unless we completely change the way we package our products, we will be at a competitive disadvantage.

Effective. Smart Stores has challenged us to provide an innovative merchandising system to display our personal care products in-store during the holiday season. If we are not their vendor of choice, our sales loss will be crippling.

With this understanding of the TTW process, let’s see how the Oral-B professional sales group used the five TTW principles, structured hourglass approach, and umbrella statement to reverse its stumble in the U.S. market and create a coordinated global unit that helped Oral-B drive accelerated sales growth.

Michelle and her team began by scoping the umbrella statement. From data already on hand, it became clear that the professional SG was a talented global organization whose ability to secure professional recommendations and endorsements from dentists and dental hygienists significantly impacted the purchase of manual and power toothbrushes in every major market where Oral-B operated. (In markets like Japan and Korea where it had no presence, sales suffered.)

This was the good news, but the list of concerns was lengthy, including an unclear understanding by the SG members of their real roles and responsibilities. There were no best practices, for example, that spelled out which of the 167,000 dentists and 110,000 hygienists in North America the 300 plus SG members should visit and how frequent those visits should be.

“We looked at call coverage across the world,” Michelle says. “How many dental offices in each marketplace were being called on, the number of calls we were making per year, and how efficient they were. We could see there was a vast difference in how often and what the call practices were in each marketplace relative to the United States where we had a detailed understanding of the right call practice.

“We had a very inconsistent approach across the world, even in marketplaces where dental practices were similar. We should have had a similar call practice, but we didn’t. We also didn’t have a similar way of looking at dental schools and dental hygiene schools and how many we should visit and how often we should visit them.”

There was no research that confirmed the best staffing levels, the best spending levels for marketing materials or for product sampling, and the right mix of activities to undertake. Despite the SG’s importance and its positioning as a global organization, within the SG it was pretty much every man and woman for himself or herself.

Assembling more facts and data marks the next phase of TTW (Figure 3.3), which addresses the umbrella statement by answering the question: What do we know? It is important to cast a wide net for information that is the basis for what is called a situation assessment.

FIGURE 3.3. WHAT DO WE KNOW?

Michelle and her team established a clear umbrella statement: The SG’s inconsistent approaches around the world and the lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities were undermining Oral-B’s marketplace performance, allowing key competitors to make gains at Oral-B’s expense. Without a clear global vision that provided the basis for well-defined practices and responsibilities, further losses would increase and steepen. So they began putting together a situation assessment.

As they started, Michelle and her team used one of the TTW frameworks, known as the seven Cs. The TTW frameworks are invaluable aids that enable us to initially chunk or compartmentalize facts and later assess their meaning and relevance by viewing them within a broader context. The seven Cs are: category, company, customer, consumer, community, colleagues, and competitors.

We won’t go through all the Cs, but let’s briefly review some of the findings. Oral-B SG’s category of dental professionals around the world was huge with 1.3 million in the top markets of Europe, Latin America, Asia Pacific, Africa, and the Middle East. Each market was segmented into clusters based on their estimated profit potential. Argentina, Chile, and South Africa, for example, were markets that were being invested in for results. The United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Brazil were markets where the SG had to win the battle, while China, India, and Turkey were areas for “testing the waters.” While Oral-B’s professional sales revenue was close to $100 million in North America and nearly $20 million in the rest of the world, only North America was profitable with a margin of 25 percent. The rest of the world ran at a loss.

The customers were diverse consisting of key opinion leaders, academic associations, specialty dentists, and general practitioners. The approaches to reach them involved a complex marketing model that used many marketing tactics—everything from direct mail, sampling, and waiting room materials to association sponsorships, guest lecture boards, symposia, and communications to dentists and hygienists. Emphasis and use of the different tactics varied widely with most tactics randomly applied across different geographies, and many resources were misdirected.

Consumer impact, detailed by country, invariably was impressive. For example, the percentage of Oral-B’s purchases influenced by dental recommendations was more than 50 percent in the United States; nearly 30 percent in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Germany; and mid 20 percent in Italy, Spain, and Australia.

Company process, systems, and structures were both limited and inconsistent. The ratio of headquarters and regional management to field workers was very low. And in the regional offices that covered Asia Pacific, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East, there were no dedicated managers. “You had this big organization that everybody thought was valuable hidden in all sorts of unusual places in the P&L with no real way to actually understand who they were and what they were doing,” says Michelle.

“And there was virtually no headquarters support. People around the world were placed in different structures with virtually no management support. You had one or two field people in every one of the global markets, sometimes 10 or 11, on their own, doing their own thing, creating their own marketing materials. There was a tremendous amount of duplication of effort and messaging.”

While Oral-B headquarters had a global strategy for its business, the then current professional process varied greatly from those guidelines in its actual local tactics and execution.

As it looked at competitors, it noted that while Oral-B had a significant professional force, on average, it was smaller than the key competitors in the top markets.

This represents a very small portion of the total fact base gathered by Michelle and her team. The robust data prepared them for the next phase of the TTW process—preparing a SWOT analysis.

Moving from assembling facts and data to culling them and assessing what’s most important (see Figure 3.4) is the next phase of TTW. The importance of facts is largely determined by tying them back to their relevance in addressing the umbrella statement. Not everything we know helps in this effort.

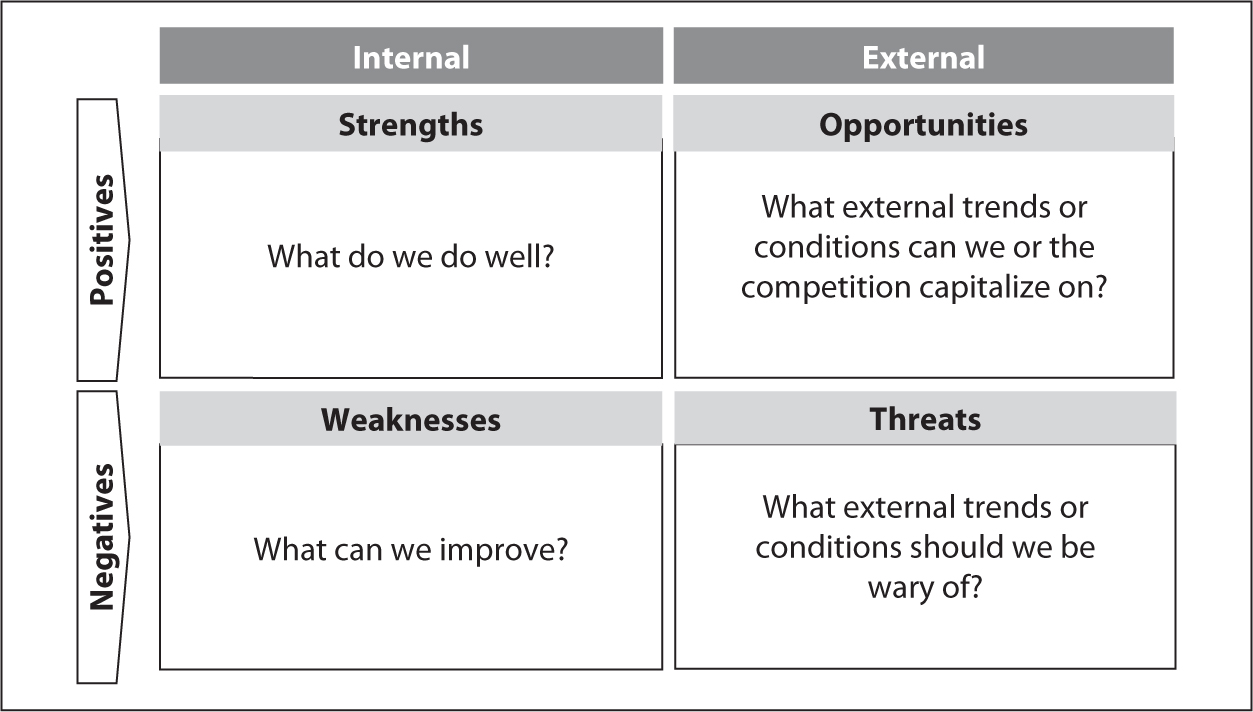

In a SWOT analysis, the S and W look inward at strengths and weaknesses. Both relate to conditions within the company (or even individuals). The O and T look outward at opportunities and threats coming from beyond. The SWOT framework is organized into quadrants within a matrix (Figure 3.5) with positive factors at the top, and negative factors below. For strengths, we attempt to answer the questions: What do we do as well or better than our competitors? What enables us to outperform our competitors? For weaknesses, What can we improve? What are our resource, service, or product shortcomings? When we look outside at opportunities, we ask and answer: What external trends or conditions can we (or our competitors) capitalize on? Could new technology improve our performance? And for threats: What trends or conditions should worry us? Are new competitors entering our markets? Are demographics changing?

FIGURE 3.5. SWOT FRAMEWORK.

Source: Global Edge LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Working from their seven Cs data, Michelle’s team members filled in SWOT. The strengths were impressive:

![]() Dental sales professionals significantly impact consumer purchases in power and manual toothbrushes.

Dental sales professionals significantly impact consumer purchases in power and manual toothbrushes.

![]() Oral-B leads in use and recommendations by dentists in most markets.

Oral-B leads in use and recommendations by dentists in most markets.

![]() Oral-B was acknowledged for its strong leadership position in clinical brushing research.

Oral-B was acknowledged for its strong leadership position in clinical brushing research.

![]() Professional sales activities were partially self-funding.

Professional sales activities were partially self-funding.

![]() Oral-B was a strong trusted brand.

Oral-B was a strong trusted brand.

And there was a list of weaknesses:

![]() Programs and practices were inconsistently applied across regions.

Programs and practices were inconsistently applied across regions.

![]() Management of professionals was deficient.

Management of professionals was deficient.

![]() Roles, responsibilities, and priorities were unclear on securing recommendations versus selling products.

Roles, responsibilities, and priorities were unclear on securing recommendations versus selling products.

![]() Product sampling was limited.

Product sampling was limited.

The external trends served up several opportunities:

![]() Consumers trust branded products in the oral care category.

Consumers trust branded products in the oral care category.

![]() Dentists and hygienists significantly affect the purchase of power toothbrushes.

Dentists and hygienists significantly affect the purchase of power toothbrushes.

![]() The power toothbrush business is in underdeveloped markets.

The power toothbrush business is in underdeveloped markets.

![]() Increased demand for dental care in developing markets.

Increased demand for dental care in developing markets.

Competitive threats also were strong:

![]() Sonicare was aggressively expanding its professional group globally.

Sonicare was aggressively expanding its professional group globally.

![]() Competitors such as Colgate could better leverage their reputation for excellence in toothpastes, mouthwashes, and other product categories.

Competitors such as Colgate could better leverage their reputation for excellence in toothpastes, mouthwashes, and other product categories.

![]() Acquisitions and consolidations were likely.

Acquisitions and consolidations were likely.

We return to Michelle’s story in the next chapter, but let’s look now at a SWOT analysis for a different type of organization, a not-for-profit organization—an inner city charter school. Its SWOT analysis might look something like what’s shown in Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1. SWOT ANALYSIS OF INNER CITY SCHOOL

Getting It Right

Poorly done, a SWOT analysis can create big problems. “When I became the leader at one business I ran,” says Gary Cohen, “I inherited a few SWOT analyses that weren’t worth the paper they were written on. Based on one of them, we had entered a new high-end merchandise category, and it was a mistake. The decision had been entirely based on the ‘O’—opportunity, the chance to reach for this shiny star they wanted to go after. There was no linkage back to what we as a company were good or bad at. Nobody connected the dots. This category was growing, but the organization didn’t have any particular strengths there. We weren’t very good at dealing with the necessary distribution channels, and nobody ever figured out that we would have to build a specialized sales team from scratch. Beyond that, the downside of selling high-end merchandise if a market declined was never explored. When the economy did go south, we got killed.”

What’s Our Point of Difference? From SWOT to Strategic Competitive Advantage

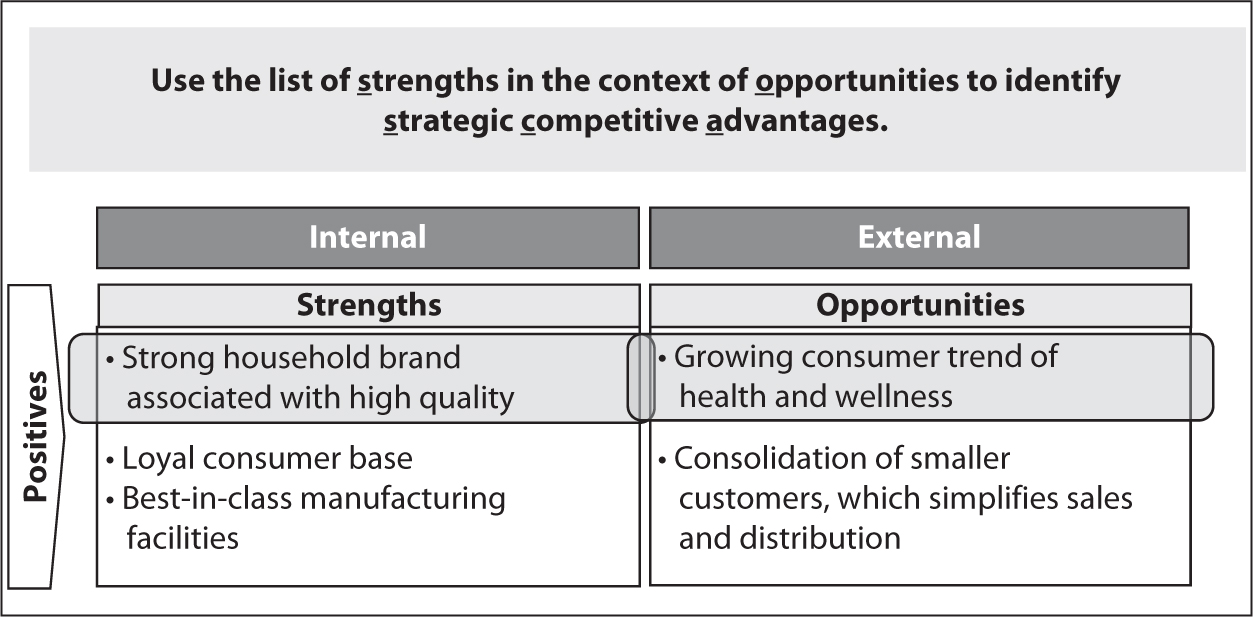

At this time, let’s look at our SWOT analysis so we can search for a “sweet spot of strengths,” which we call our strategic competitive advantage, or SCA.

Our strategic competitive advantage is a superstrength, something we do better than anyone else. It’s what truly distinguishes us from our peers or competitors. As Figure 3.6 illustrates, identifying the significant points of difference is the next step in TTW.

FIGURE 3.6. WHAT DIFFERENTIATES US?

Our SCA is why we can be secure that we will continue to be successful. Nolan Ryan was in the baseball business, and he remains one of the greatest pitchers of all time. Batters couldn’t hit his pitches—he averaged more than one strikeout per inning over his career. His trademark was a blazing fastball, which was regularly clocked at over 100 miles per hour. This was his super-strength, his strategic competitive advantage, which he sustained year after year for much of his lengthy career.

Our SCAs separate us from the pack. Sometimes those SCAs are short-lived. But more durable competitive advantages, those lasting three years or more, are sustainable SCAs. And there are a number of factors that make a SCA sustainable:

![]() A breakthrough superior product that cannot easily be duplicated, especially one protected by trademark or patent (Botox, Gatorade, Star Wars, Angry Birds).

A breakthrough superior product that cannot easily be duplicated, especially one protected by trademark or patent (Botox, Gatorade, Star Wars, Angry Birds).

![]() A superior supply chain cost position (cornering the hazelnut market, if you’re Nutella).

A superior supply chain cost position (cornering the hazelnut market, if you’re Nutella).

![]() Specialized know-how (oil spill cleanup, Hubbell telescope repair).

Specialized know-how (oil spill cleanup, Hubbell telescope repair).

![]() Strong brand equity (Coca-Cola, Chanel, Tiffany, the New York Yankees).

Strong brand equity (Coca-Cola, Chanel, Tiffany, the New York Yankees).

When Toyota pioneered hybrid vehicles with the innovative Prius, it had almost the entire market for several years. Until other carmakers were able to respond, Toyota had a sustainable strategic competitive advantage. Mickey Mouse is a beloved worldwide icon and has been a sustainable SCA for the Walt Disney Company since the 1930s. Looked at in this light, Nolan Ryan was a sustainable SCA for whatever team he played on. He was one of a kind with a superior product that would never be duplicated. His major league career spanned 27 years, and the speed of his fastball was undiminished for more than two decades. Because sustainable SCAs are so valuable—and rare—they are worth pursuing.

Identifying an SCA means taking an in-depth look at our positives and negatives. Here’s an example. All Clean is a company that manufactures a line of antibacterial hand wipes. When it conducted its SWOT analysis, its strengths were strong brand name recognition, a reputation for making a quality product, and a loyal base of repeat customers. Weaknesses included shelving inconsistencies—not being stocked in the aisle where most consumers expected to find its products—and the perception that the products were more expensive and less convenient than competing liquid hand sanitizers.

Opportunities for All Clean included a growing consumer focus on health and wellness, specifically a heightened awareness of the importance of clean hands; an increasingly mobile society, with its demands for convenient, on-the-go products; and several winters with virulent, widespread flu outbreaks. It’s worth underscoring for all businesses that opportunity can reside in “bad news.” (For example, Duracell sells more batteries with a hurricane looming, and companies specializing in roofing, construction, and carpet cleaning also view storms as destructive events that create more business.) External threats identified by All Clean included aggressive competition from other brands and private labels, and well-publicized statements from healthcare professionals, promoting soap and water, not hand wipes, as the “gold standard” for cleanliness. (See Table 3.2.)

TABLE 3.2. ALL CLEAN HAND WIPES

How did All Clean look at its SWOT analysis to find its sustainable strategic competitive advantage? By connecting the dots. It coupled its number one internal strength with its number one external opportunity, and linked its strong, positive brand identification with the emerging trend in consumer awareness of health and wellness issues. (See Figure 3.7.)

FIGURE 3.7. FROM SWOT TO SCA

Source: GlobalEdg LLC. All Rights Reserved.

As the senior managers at Jamba Juice sought to identify its SCA, they reviewed the strengths that still defined the company despite the tough times it had experienced. It had innovation skills that virtually ensured a flow of new products. It had scale within the very fragmented smoothie and juice category that was characterized by mom-and-pop stores and small local chains. Its individual stores had sales volumes that were twice as large as its nearest competitor. Its base of consumers in California, the biggest smoothie and juice market in the country, was large and growing, giving it a dominant market share. The supply chain that provided Jamba with the necessary goods (everything from fresh fruits to napkins and straws) and services was solid.

The company culture, deeply grounded in the belief that Jamba’s mission was to inspire and simplify healthy living, was very strong. Jamba’s products were superior to its peers’ in their taste, quality, and wellness benefits. And their portability was a perfect fit for an active on-the-go lifestyle. Importantly, the Jamba Juice brand was iconic. Awareness of the brand extended far beyond its actual size and even its geographic distribution. And mere mention of the Jamba Juice name brought a smile and warm feelings both to ardent fans and even light users.

So there were many strengths from which Jamba identified the top five as: scale in the segment; company culture; product taste and quality; wellness benefits; and portability. These five were viewed as sources for Jamba’s competitive advantage. And when Jamba looked for a sustainable competitive advantage, all agreed it was the Jamba Juice brand—a powerful equity that should be enduring and provide a platform for growth for many years to come.

Chapter Summary

![]() TTW harnesses the power of asking the right questions in the right order. The hourglass is the structure that guides us through the process.

TTW harnesses the power of asking the right questions in the right order. The hourglass is the structure that guides us through the process.

![]() Clearly defining the umbrella statement to frame the scope, provide direction, and secure alignment on our issue goes a long way toward determining our success in addressing it.

Clearly defining the umbrella statement to frame the scope, provide direction, and secure alignment on our issue goes a long way toward determining our success in addressing it.

![]() The step-by-step process of TTW leads us through convergent thinking to use the seven Cs framework and SWOT analysis to compile our data and fact base and identify our strategic competitive advantage.

The step-by-step process of TTW leads us through convergent thinking to use the seven Cs framework and SWOT analysis to compile our data and fact base and identify our strategic competitive advantage.

By answering the questions what do we know?, what is important?, and what differentiates us? we are halfway through the top of the hourglass. This knowledge is powerful, but we still have to know what to do with it. In Chapter 4, we look more closely at how we use our findings to formulate conclusions and examine strategies.

Chapter 3 Exercises

Here are some questions and exercises to guide you in applying the TTW principles. As you spend time with each of the principles, your overall competence in thinking strategically will improve. So spend the time, and the results will follow.

What Are We Trying to Solve?

Mastering a TTW Umbrella Statement

The umbrella statement lies at the heart of the Think to Win process. “What, exactly, are we trying to solve?” The first and most important step in the TTW methodology is identifying the big issue. By identifying where the problem begins, the correct place for analysis is pinpointed and you can now begin to address the challenge! Consider the following questions:

![]() What are you trying to solve? Must be answered.

What are you trying to solve? Must be answered.

![]() Who can help me best define it?

Who can help me best define it?

![]() What am I trying to change?

What am I trying to change?

Exercise: Creating an Umbrella Statement

(Can be done at individual or group level)

1. Individually consider the question: “What am I really trying to solve?”

2. Capture in one to two sentences.

3. Review with the following criteria in mind:

![]() Is it clear and succinct?

Is it clear and succinct?

![]() Is it focused?

Is it focused?

![]() Is it free of solutions?

Is it free of solutions?

![]() Is there tension and a sense of urgency (what is at risk)?

Is there tension and a sense of urgency (what is at risk)?

4. Have a conversation with other stakeholders to clarify issues and gain alignment.

5. Output: an umbrella statement that will set the stage for your analysis.

What Do We Know?

When we complete our umbrella statement, we start to identify and process what we know about our issue or problem. We want our fact base and data gathering to be robust but not overwhelming.

Mastering the Use of TTW Frameworks

Employ the use of TTW frameworks to identify and capture critical data. TTW frameworks are great tools that can guide you through the process of capturing and sorting your information.

The Seven C Framework

Utilize a seven C framework to “bucket data” for focused analysis. List the data most related to the issue. Collect only the facts that are most relevant! Ask, Why is that important for us to know?

For internal analysis ask: What do we know? What is going on inside the company?

![]() Company. Everything going on within the company, except people. This would include financials, structure, history, products, brand, vision, systems, mission, and values. All these data go under company.

Company. Everything going on within the company, except people. This would include financials, structure, history, products, brand, vision, systems, mission, and values. All these data go under company.

![]() Colleagues. Everything that relates to people: employee morale, engagement, capabilities, competencies, skills; anything that would normally be examined under “people.” (It is often called “people;” it’s modified here to fit the seven C terminology.)

Colleagues. Everything that relates to people: employee morale, engagement, capabilities, competencies, skills; anything that would normally be examined under “people.” (It is often called “people;” it’s modified here to fit the seven C terminology.)

For external analysis ask: What do we know? What is going on in the external marketplace?

![]() Category. Where do you and your competitors “do battle in the marketplace”? You may be in several categories, depending on the company and products.

Category. Where do you and your competitors “do battle in the marketplace”? You may be in several categories, depending on the company and products.

![]() Customers and consumers. These could be one and the same or completely different.

Customers and consumers. These could be one and the same or completely different.

![]() Competitors. Whomever you are “doing battle with” or competing against within the category.

Competitors. Whomever you are “doing battle with” or competing against within the category.

![]() Community. Think of the word STEEP—Social trends (see the mnemonic that follows); what trends are happening in society, in the environment in which you live?. How is technology advancing? Is the macro economic climate changing? Are environmental concerns heightening? Is the political and regulatory climate becoming more or less favorable?

Community. Think of the word STEEP—Social trends (see the mnemonic that follows); what trends are happening in society, in the environment in which you live?. How is technology advancing? Is the macro economic climate changing? Are environmental concerns heightening? Is the political and regulatory climate becoming more or less favorable?

Exercise: Populating a Framework

(Can be done at individual or group level.)

1. Use the seven C situational assessment framework to capture relevant internal and external information.

2. Support your findings with relevant facts.

3. Ask whether this information links to the umbrella statement.

4. Make sure all the “Cs” are represented with relevant data.

5. Have a conversation with other stakeholders to clarify and gain alignment.

6. Output is a seven C analysis that will set the stage for determining strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

The deliverable is a completed section of framework to inform your SWOT analysis.

What Is Most Important?

We need to carefully examine the information we have to determine what is most important. The TTW approach to a SWOT analysis provides us with a valuable tool.

Mastering the SWOT Tool to Drive TTW Thinking

For internal strengths and weaknesses, ask the questions: What do we do really well? What don’t we do really well? When answering the questions, remember to see through the lens of the competition! Is it a real strength?

For external opportunities and threats, consider the following:

![]() These are trends in the marketplace; the marketplace is moving at warp speed, making it harder to foresee the future.

These are trends in the marketplace; the marketplace is moving at warp speed, making it harder to foresee the future.

![]() At this point, an opportunity is an opportunity for both your organization and the competitor; it is not yet an action. It is a trend.

At this point, an opportunity is an opportunity for both your organization and the competitor; it is not yet an action. It is a trend.

Set the information up in a four-quadrant matrix that aligns positive factors, both internal and external, and negative factors, both internal and external, with one another, as shown in Figure 3.8.

FIGURE 3.8. A SWOT TOOL.

Exercise: Creating a SWOT Matrix

This exercise can be done at individual or group level.

1. Gather your framework (seven Cs).

2. Create four charts—one for each letter of SWOT.

3. Use the internal Cs to determine strengths and weaknesses.

4. Use the external Cs to determine opportunities and threats.

5. Use Figure 3.8 to capture your information.

6. Have a conversation with other stakeholders to clarify and gain alignment.

The deliverable is a completed draft of a SWOT analysis.

What Differentiates Us?

Understanding our significant points of difference helps us develop a list of our sustainable advantages.

Mastering How to Identify a Strategic Competitive Advantage

Ask yourself the following:

![]() What is the source of our competitive advantage?

What is the source of our competitive advantage?

![]() Does this separate us from the competition?

Does this separate us from the competition?

![]() Does it really provide us with leverage and margin in the marketplace?

Does it really provide us with leverage and margin in the marketplace?

![]() Using the SWOT analysis, focus on the strengths:

Using the SWOT analysis, focus on the strengths:

![]() What is the source of our competitive advantage? What makes our organization unique?

What is the source of our competitive advantage? What makes our organization unique?

![]() What is our sustainable competitive advantage? How long can we hold it? Three years is the rule of thumb.

What is our sustainable competitive advantage? How long can we hold it? Three years is the rule of thumb.

Ask thought provoking questions such as: What is Toyota’s competitive advantage? Apple’s? Our competitors’? Who are the competitors we might not be thinking about?

Exercise: SCA

This exercise can be done at an individual or group level.

1. Use the strength section of the SWOT analysis. Determine the SCA for your organization.

2. Answer the following questions:

![]() What really differentiates us?

What really differentiates us?

![]() Is it a source or sustainable?

Is it a source or sustainable?

![]() If it exists, how do we retain it?

If it exists, how do we retain it?

![]() If it does not exist, what do we need to be thinking about to create one?

If it does not exist, what do we need to be thinking about to create one?

3. Have a conversation with other stakeholders to clarify and gain alignment.

The deliverable is that the SCA is identified and aligned.

Organizational Assessment

Use the following table as a checklist for identifying TTW principles and practices. This will help you to better understand where your organization needs to focus your energies. To get an idea where you believe your organization stands, read through each statement and jot down a rating from 1 to 5:

Review individual items. Look for items where your organization scored lower (3 and below) and think about the following questions:

![]() What do I believe is driving the score?

What do I believe is driving the score?

![]() What do I need to stop, start, or continue doing?

What do I need to stop, start, or continue doing?