The Top Talent Challenge

In 2006, Anne Erni was in love—with her job. “I was in an organization that really valued what I was doing,” recalls the former chief diversity officer of Lehman Brothers. “I was getting so much positive feedback from every part of the firm. It was such an amazing adrenaline rush.”

That rush carried Erni through workweeks that involved back-to-back meetings followed by elevenhour days when, she says, “I would have to deliver what I promised in those meetings.” At least one night a week, Erni had a speaking engagement or a professional dinner to attend, and at least one night, she stayed at work until midnight and then faced the commute back to New Jersey, her husband, and two kids.

Her hefty paycheck only reinforced her dedication. “Every year my pay went up—sometimes significantly. I knew that the more I worked, the more I got done, the more I earned. So that drove me, too.”

A year later, the first rumblings of the coming cataclysm began to shake the financial industry and the layoffs began. Erni’s boss and mentor stepped down. By July 2007, Erni’s budget had been slashed to the bare amount necessary to cover commitments. “It wasn’t about being proactive anymore; it was just about getting by,” she says.

A second round of layoffs ensued. By August 2008, Erni was starting to question the viability of the job she had adored. “The pain of seeing everything come apart all around me was really hard to bear. For the first time in my career, I started to get disillusioned.”

Erni stopped working long hours, and, once she began to spend more time at home, “I realized how much I had not been doing for my family. I hadn’t gone on my son’s field trips, I had delegated a lot. And I thought, ‘Oh, my god, what did I miss?’”

Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008. Erni was laid off in November, and by that time the joy of her work had drained along with her 401(k) account.

The Talent Time Bomb

Anne Erni’s trajectory, it turns out, is typical—not only of the financial industry, with its outsized demands and outsized rewards, but also of high-potential employees in every sector.

When the Center for Work-Life Policy’s Hidden Brain Drain Task Force first began to study top performers in 2006, it was a heady time, with the global economy firing on all cylinders. Strategic planning committees routinely asked not whether to expand but how much. There was a sense among top performers that limitless rewards were within reach if they only stretched a little further.

The concern that dominated our study was a simple one: how far was top talent willing—or able—to stretch before reaching the breaking point? In a series of surveys and focus groups, we targeted professionals who worked at least sixty hours per week, were in the top 6 percent earnings bracket, and held positions with at least five of the following performance pressures: unpredictable workload; fast-paced work with tight deadlines; work-related events outside regular hours; 24/7 availability to clients; a great deal of travel; a scope of work that amounted to more than one job; responsibility for profit and loss; responsibility for recruiting and mentoring; a great many direct reports; more than ten hours a day of face time; and insufficient staffing. This elite group—think of them as the Delta Force of the workplace—comprised men and women of all ages and at all stages of their careers employed in a wide range of industries. We explored why they loved their jobs, what motivated them to work so hard, what personal goals they were willing to trade for professional success, and whether that success was ultimately worth the sacrifices.

Our findings described a balancing act, a reciprocal deal. Top talent was willing to pull out all the stops—work seventy-hour weeks and cope with a myriad of performance pressures—as long as companies came through with rich rewards: intellectual challenge, recognition, and comp packages to die for. In other words, companies were able to hold on to these engines of productivity and growth as long as companies ponied up the goods.

We concluded that the top talent model was “in equilibrium.” This model had tensions and flaws, which particularly impacted women, but by and large it was working. In the ebullient, expansive world of 2006, the rewards of top jobs were outsize enough to justify the outsize effort they required. Little did we know we were sitting on a talent time bomb. Shortly after we completed the study, the subprime mortgage crisis triggered a brutal economic downturn. There were knock-on effects everywhere.

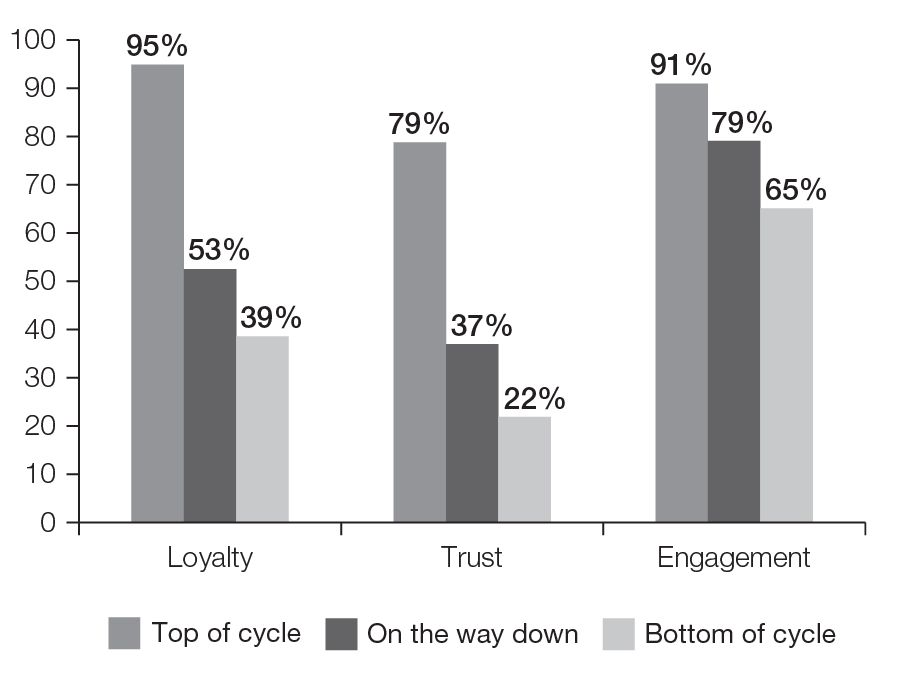

Spurred by these distressing events, we revisited the talent model in the period of March to July 2008, when the first ominous tremors were beginning to shake the global economy, and again in December 2008, when the foundations had shattered. From Wall Street to Main Street, top performers’ loyalty, trust, and engagement had fallen steeply. Figure 1 shows what happened at seven Wall Street firms at the epicenter of the crisis. For top talent, the reciprocal deal was over.

The talent time bomb: loyalty, trust, and engagement fall off a cliff

What would it take to pick up the pieces? Would it even be possible?

The View from the Top of the Cycle

In 2006, the most salient finding was how much top performers loved their jobs. They loved the intellectual challenge and the thrill of achieving difficult goals. They loved the stimulation of smart colleagues and the camaraderie of a well-tuned team. They were addicted to the adrenaline rush of the next tough assignment. Far from seeing themselves as overworked drones, they wore their commitments like a badge of honor. Two-thirds of survey respondents in our study said that the pressure and the pace of their jobs were selfinflicted. Although clearly they were aware of the toll their jobs took on their lives outside the office, most of the high achievers felt that the sacrifices—as well as the stress and strain—were justified by the rich rewards.

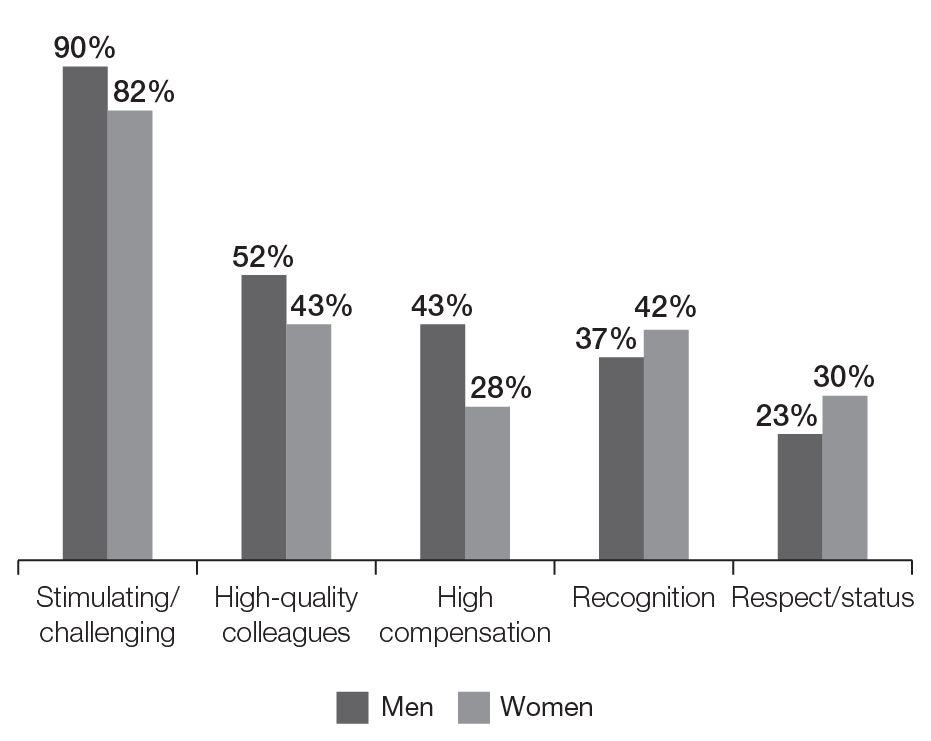

What were these rewards, and how did top talent rank them? A large majority stressed the challenge and stimulation of the work; this was the top pick for men as well as women. Compensation, recognition, status, “meaning and purpose,” and flex options were also important motivators. Interestingly, money wasn’t the prime driver. It was important but not dominant. As shown in figure 2, less than half (40 percent) of respondents in our surveys rated high levels of compensation as the main reason they loved their jobs. Only in the financial sector, with its tradition of outsized bonuses, did that figure edge over the 50 percent mark (56 percent).

Note that among female top talent, monetary rewards were trumped by four other factors. In focus groups high-performing women (and at least some men) talked about the importance of respect and recognition—from bosses and companies—and the satisfaction they derived from working with a group of great colleagues.

Why top performers love their jobs

Whatever the complexities of the motivational map, the outsize efforts expended by this Delta Force of the workplace came at a huge personal cost. Our surveys revealed that men and women alike were teetering on the brink of a cliff. Their overdrive work model was taking a toll on their personal and family lives—even their sex lives—to a degree that threatened their well-being. A significant number (59 percent) of survey respondents said that work pressures were undermining their health, and 40 percent felt that their jobs were undermining their relationships with spouses or partners. Women felt the pain especially keenly. Although men and women perceived the stress at work in much the same way, women were disproportionately tuned in to stress at home, seeing a direct link between their long workweeks and a variety of distressing behaviors in their children: watching too much television, eating too much junk food, underachieving in school, and acting out.

Men as well as women were aware that they were performing a delicate balancing act. The promise of significant payback—power and purpose as well as compensation—would keep them in harness for a number of years, but down the road a significant minority of these high-echelon professionals wanted to trade in their jobs for something less stressful.

The View from the Bottom of the Cycle

Then, in 2008, the financial crisis and economic collapse tore through the top talent model like a hurricane.

The most sobering finding of our 2008 research was that for high performers the joy of work evaporated overnight. In its place was an anxiety so pervasive that, as one strategy session participant reported, “At night I’m tossing and turning and grinding my teeth so badly that I’ve developed cracks in my molars.” Hidden Brain Drain survey data shows that 50 percent of high-echelon workers have experienced at least one negative health effect as a result of the downturn.

Love for one’s job—and, by extension, the organization—was being choked off by insecurity and betrayal. Compensation packages that relied on company stock options were a bitter pill to swallow, as swooning stock prices vaporized the accumulated rewards of years of hard work. The suddenness of the change was especially shocking. People reported losing their sense of balance—of equilibrium—as everything they had counted on was jarred out of place.

Respect and recognition gave way to a bunker mentality, with everyone fighting for a space in a small and insecure shelter. In an interview, a senior Wall Street executive talked about the corporate culture “turning tribal.” Supervisors were busy placating frantic clients and figuring out whose job to cut in the next round of layoffs, leaving them little time to pay attention to their former stars, who inevitably felt neglected. Colleagues were too panic stricken or too busy trying to protect themselves to extend the camaraderie that formerly sparked ideas and made the workplace congenial. Teams were torn apart as head count was cut. Survivors facing threats to their own job security were shouldering heavy workloads (81 percent compared with 61 percent a year earlier) and coping with tremendous face-time pressure (55 percent compared with 22 percent a year earlier), and that forced them to put in even longer hours. (Hidden Brain Drain January 2009 survey data shows that 22 percent of high-echelon workers are now working an extra nine hours a week.)

In this punishing work environment, loyalty, trust, and engagement have almost evaporated. With star status no longer a guarantee of respect, job security, or compensation, the number of employees on Wall Street who trust their organizations plunged from 79 percent in June 2007 to 22 percent in December 2008; on Main Street, it sank from 85 percent to 56 percent over the same time period. Loyalty has also plummeted, falling from 95 percent to 39 percent on Wall Street, and from 88 percent to 71 percent on Main Street. The figures on engagement levels are particularly disturbing, dropping from 91 percent to 65 percent on Wall Street, and from a nearly perfect 97 percent to a middling 85 percent on Main Street.

The survivors of the RIFs (reductions in force) are having a hard time focusing on the work at hand. When participants in Hidden Brain Drain strategy sessions were asked to tell us the first word that came to mind when describing their current work environment, they said, “thankless,” “chaotic,” “stressful,” “frustrating,” “overwhelming and unsustainable,” “depressing,” and just plain “sad.”

Strategy session participants described the level of stress generated by the economic downturn as “physically and mentally crippling.” Nearly eight of ten participants reported extremely high levels of stress, more than twice the number as one year earlier, with symptoms ranging from ulcers and migraine headaches to a new dependence on sleep medication. Typical comments included “I can’t focus on work—I’m too distracted by tensions in my gutted team and worries about my job” and “I probably should be working out, but given the relentless bad news, all I can deal with at the end of a stress-filled day is a stiff drink.”

As employees struggled to cope, negative strategies —such as taking sleeping pills, drinking, smoking, biting one’s nails, overeating, and losing one’s temper—trumped positive ways of coping. Work-related stress transformed Dr. Jekylls into Mr. Hydes, as parents reported “yelling at the kids more than I like” and spouses noted “more stupid fighting.” In June 2007, 30 percent of respondents were struggling with eating issues and 23 percent with drinking issues. One year later these figures had risen appreciably, to 41 percent and 30 percent, respectively. Weight issues were also on the rise, with respondents saying, “I would love to [exercise regularly] but I just don’t have time.” Not very long ago, high-octane jobs made members of the workplace Delta Force feel special and worthwhile, but now these same jobs were turning them into people they didn’t know and didn’t like.

Key Facts

Loyalty, Trust, and Engagement

- On Wall Street, loyalty has plummeted from 95 percent in June 2007 to 39 percent in December 2008. On Main Street, loyalty fell from 88 percent to 71 percent.

- Trust has plunged from 79 percent to 22 percent on Wall Street over the same period; and from 85 percent to 56 percent on Main Street.

- Engagement on Wall Street has dropped from 91 percent to 65 percent. On Main Street, it has fallen from 97 percent to 85 percent.

Body Blows and Fallout in Personal Life

- 59 percent of respondents said that work pressures were undermining their health (65 percent on Wall Street).

- 40 percent felt their jobs were undermining their relationship with spouses or partners (50 percent on Wall Street).

- 78 percent of high-echelon workers reported experiencing high levels of stress, more than twice as high as one year earlier.

- Symptoms range from “crashing” at the end of the day (70 percent versus 43 percent six months earlier) to an “emptied out” sex life (37 percent versus 30 percent six months earlier).

Key Pressure Points

- Survivors of layoffs experience heavier workloads (81 percent compared to 61 percent one year earlier) and tremendous face-time pressure (55 percent compared to 22 percent).

- In January 2009, 22 percent of high-echelon workers report working an average of nine extra hours per week compared to six months earlier.

Men, Women, and Flight Risk

- 64 percent of Wall Street survivors and 41 percent of Main Street employees were considering leaving their current companies.

- Twice as many women as men on Wall Street (84 percent compared to 40 percent) were considering leaving their employers.

- Fewer than a quarter (22 percent) of women who had “one foot out the door” in December 2008 planned to take time out of the workforce.

Disengagement on Wall Street

- Employees in the financial sector reported feeling paralyzed (74 percent), demoralized (73 percent), and demotivated (64 percent).

One Foot Out the Door

When top talent feels this way it’s bad news for any organization. CEOs cannot blithely assume that valued employees will be so grateful for a job—any job—that they’ll put in the hours and the effort no matter how bad the working conditions are. There are two serious risks: top performers will walk away (and competitors are always on the prowl for proven producers), or they will settle in to what one strategy session participant called “long-term limbo,” clinging to a steady paycheck but tamping down commitment. In the words of another participant, “I quit but stayed on the job.”

How serious is the flight risk? Recent research shows it to be more substantial than expected. A Harvard Business Review article (May 2008) shows attrition after a layoff to be much deeper than the layoff itself: in this study 31 percent of survivors walked out the door in the wake of a relatively modest layoff. Hidden Brain Drain strategy sessions also uncovered significant flight risk; 64 percent of survivors on Wall Street were considering leaving, and 24 percent were actively looking for a job. Among these, 35 percent anticipated going to a competitor, 29 percent wanted to switch to a less risky industry, and 15 percent were planning to start their own businesses. “The loyalty of the institution to its people, and vice versa, isn’t really there anymore—it’s a different animal from what a lot of us were used to,” muses a partner at a whiteshoe New York law firm that recently announced it would lay off two hundred lawyers. “The problem is we’re supposed to all be in this together. But at some point, you stop and think: ‘Well, maybe we’re not.’”

Interestingly, in this downturn, flight risk continues to be differentiated by gender. Strategy session data revealed that twice as many women as men were considering leaving their employers, and many more women than men were actively looking for another job. In a way, that’s not surprising: women are constantly recalibrating at the margin, calculating whether the professional benefits of their jobs outweigh the costs. In the words of one woman, “When I walk out the door in the morning, leaving my two-year-old with the babysitter, there’s usually a bit of a scene. Tommy clings, pouts, and whips up the guilt. Now, I know it’s not serious—most of the time he likes his sitter. But it sure makes me think about why I go to work—and why I put in a ten-hour day. It’s as though every day I make the following calculation: do the satisfactions I derive from my job (efficacy, recognition—a sense of stretching my mind) justify leaving Tommy? These days it’s a close run.”

Recalibrating at the margin is encouraged by the fact that a significant minority of high-performing women (31 percent) are married to men who earn more than they do, and therefore they can choose whether to work. All this explains why, in difficult times, more women than men are likely to head for the door.

If flight risk is a serious problem for companies, how serious are plummeting rates of engagement and “long-run limbo”?

The data shows distressing levels of disengagement. In our strategy sessions, 73 percent of participants reported feeling “demoralized,” 74 percent felt “paralyzed,” and 64 percent felt “demotivated.” Even top performers were no longer hitting previous highs. “I want to be engaged, but with things in chaos it’s hard to lock on to purpose,” said one participant who had a track record as a top producer. Another commented, “I am just not as pumped as I used to be in the mornings. There’s more dread than excitement about the day ahead.”

It’s clear that in the current environment many employees—even high-performing ones—feel they need to cling to a steady paycheck, but participants in our strategy sessions were honest about the impact of the current negative work environment on morale and productivity. “I feel betrayed. Five years of extraordinary effort just went down the drain. And no one seems to care—least of all my immediate boss. It’s easy to get cynical—to dial down and tune out—to focus on looking after number one.”

Still, plenty of the strategy session participants recognize that challenging times present opportunities for their organizations and for their own professional advancement. More important, they know exactly what it takes to recharge their energies.