New modes of scholarly communication: implications of Web 2.0 in the context of research dissemination

Introduction

Scholarly communication, the communication and dissemination of research ideas, initiatives, and results, has long historical roots. The process has formal structures which probably will not change very quickly. However, there have been some important turning points in recent years. The development of the Internet and the web has had a major impact on many areas in today’s society. For example, the amount of electronic information and publications has greatly affected scholarly communication and created many challenges for academic libraries. Also the characteristic of immediate availability has affected scholarly communication and we expect to get knowledge when needed. The web has also evolved from more static to user-oriented, interactive, and co-produced (O’Reilly, 2005). Social and interactive tools that are easy to use are developed so that we can share information, pictures, photos, or ideas (Miller, 2005; Notess, 2006). The social and interactive web is expected to affect the scholarly communication process where research dissemination becomes increasingly informal, interactive, and part of a much larger public than earlier.

This chapter is a literature review and explores the possible effects of new Web 2.0 tools on researchers’ scholarly communication. What are the relevant Web 2.0 tools and techniques and how are they possibly changing the process with more informal elements? Also the libraries’ role in connection to the changing research dissemination is discussed and future trends are identified.

Scholarly communication

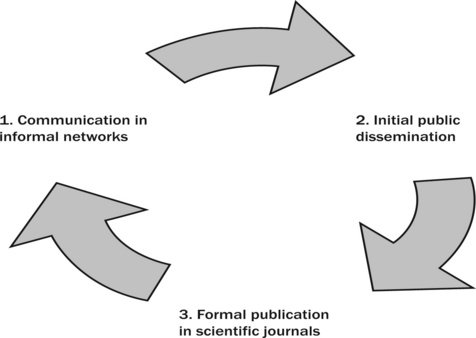

Scholarly communication is an umbrella term used to describe the process of sharing and publishing research work and findings so they are available to a wider academic community and beyond (Halliday, 2001). The scholarly communication process can be divided into three main stages (Graham, 2000). First of all there is communication in informal networks, which is a growing area because of electronic media; secondly, it is about initial public dissemination in conferences and preprints; and finally, there is formal publication of research in scientific journals.

Traditionally research has been communicated by speech and writing and this process has long historical roots. The emergence of the Internet and the web has had wide implications for research dissemination and scholarly publication. Scientists have been successful in the use of the Internet for communication and therefore the electronic format has affected scholarly publication, especially concerning availability and accessibility (Björk, 2004). The growing volume of information has also forced individual researchers to become more specialized and the forums for research dissemination are today also very specialized. This has led to differences between subject fields concerning scholarly communication. The financial status of a discipline is also an important factor affecting the methods of scholarly communication and research dissemination (Meadows, 2003). Despite these changes the distribution of scientific information has retained many of its structures. The publishers still have a firm grip on the scientific publishing business although there is widespread agreement among researchers to support open access (OA), which means a scientific publication is freely available over the Internet without any restrictions or payments. The main barriers to a wider implementation of OA publications are related to legal issues, information technology infrastructure, business models, indexing services, academic reward systems, and critical mass (Björk, 2004).

Although OA is only a marginal part of global scholarly communication, it is clear that the OA movement has brought a change to the traditional views of the libraries’ role in providing access to scholarly information, that is to maintain access to commercial journals through subscriptions. Open access was first seen as a complicated challenge as OA publications do not require scholars to use library services. However, a parallel system has emerged and the academic libraries more often see their roles as communicating the existence of OA journals and publications to users and integrating them into their digital collections (Schmidt, Sennyey and Carstens, 2005). Scholarly communication, OA, and digital libraries are broad areas of research, not discussed in detail here, but relevant for the understanding of the whole arena affecting scholarly communication.

Today the social and interactive web brings additional challenges and possible advantages to this process. The user-produced web demands new individual skills where information and media literacy are underlined. It is about the ability to learn new things, to be critical, analytical, to evaluate quality, and to use the information correctly. A new kind of network society is established where our understanding of time and space is changed (Castells, 1999–2000; Katz, Rice and Aspden, 2001; Dahlgren, 2002; Jääskeläinen and Savolainen, 2003). Will this also have implications for scholarly communication? Defining scholarly communication as a social process is obvious. Even if a scholar works alone, research in all fields requires a level of validation through a review process and sharing with others. Scholarly communication is embedded in structures of relationships with other scholars in the end (Borgman, 2000). In this respect the social and interactive web seems to have a great im-pact on the whole scholarly process and also places new demands on library services.

Social web and interactive tools

There are many examples of Web 2.0 techniques but the technologies themselves will not be presented in detail in this chapter. However, it is important to discuss the nature of Web 2.0 tools in order to illuminate the possible effects for scholarly communication. One of the most highly used features of Web 2.0 is blogging, a subjective, personal home page in diary format. Connected to the Weblogs, or Blogs, are the RSS (Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary) formats. These are one of the most significant advances in the fundamental architecture of the web, announcing new blog entries. These are also used for alerting readers to all kinds of data updates. Blogging has developed different forms and formats, of which microblogging (e.g. Twitter) is a popular phenomenon today. It consists of short messages and updates to quickly share experiences and ideas. Another well-known feature is the wiki, a web- based application for collective knowledge creation (Avram, 2006; Hasan and Pfaff, 2006). The best-known example of a wiki is Wikipedia, an online encyclopedia with open source software. It is a collaborative tool where anyone can contribute his/her knowledge. Other sites like del.icio. us and Flickr have pioneered the concept of folksonomy, a collaborative categorization of sites using freely chosen keywords, referred to as tags (O’Reilly, 2005). Also social networks like Facebook and MySpace are well-known social web tools with an increasing popularity and millions of users all over the world.

What has made Web 2.0 so popular? There are many factors but first of all the Web 2.0 techniques are technically not challenging. Also, the social and interactive features of Web 2.0 are important reasons for their popularity. It is rewarding to share experiences and information on work procedures in a blog when you know colleagues and peers will read about it and contribute their own knowledge on the topic. The exchange of views leads to more productive knowledge-sharing (Brady, 2005; Ojala, 2005). Open source technologies give the sharing visible structures on a general level and wikis and the like are therefore finding their way into the workplace, where they are seen as a possible means for employees to collectively store, edit, and access work-related material easily. The benefit of wikis lies in the fact that they help the employees to collaborate electronically by merging fragmented knowledge in the organization into more usable entities and easily accessible data (Hasan and Pfaff, 2006).

It can be concluded that Web 2.0 techniques increase one’s possibilities to explore one’s thoughts, and support or disapprove of one’s own ideas. While Web 2.0 tools are simple to use, they enable groups to self- organize, and interact more closely than before (Schiltz, Truyen and Coppens, 2007; Gray, Thompson et al., 2008). How can Web 2.0 tools support scholarly communication? There are a few studies looking at collaborative advantages through Web 2.0 (Ojala, 2005; Avram, 2006; Hasan and Pfaff, 2006; Widén-Wulff and Tötterman, 2009). These show different possibilities using social software for effective knowledge sharing and focus on the social dimension.

Scholarly communication and implications of Web 2.0

Web 2.0 tools bring clear structures to collaborative processes through networks and links. They also support the potential to develop social relations, resulting in different kinds of benefits. There are a number of studies looking at blogs, wikis, and social networks as important tools of support for learning in different environments, e.g. in the context of higher education (Craig, 2007). Hall and Davison (2007) studied blogs as a tool to encourage the interaction between students and found that blogs increased the reflective engagement with teaching material and there was also a higher level of shared peer support between class members. In earlier studies it has been shown that exchange of information in online environments is highly dependent on social relationships. Although social infrastructure often starts in the face-to-face environment, online techniques and web platforms support the development of relational ties (Hall and Widén-Wulff, 2008). Further, Web 2.0 technologies also promote a shared language and therefore collective knowledge. In an environment such as a workplace a collective view on specific problems may be mediated. The features of blogs and wikis – creating ideas, sharing knowledge, shaping communities and networks – are found to be suitable support for many knowledge processes (Klamma, Cao, and Spaniol, 2007).

In the context of scholarly communication this means we can read about and discuss research ideas and trends in a larger context than ever before. A commenting practice is emerging and it is easier to connect with other researchers sharing the same or similar ideas and viewpoints. Blogs in the context of scholarly communication are not yet very common, but the attitude to using social media is changing. In workplaces the attitudes have changed rapidly from looking at blogs as individual diaries with the description of the person’s political interests, for example, into being a more collective tool where several persons can participate and generate a wider knowledge base on a specific matter. With these features the blogs do not only reflect a personal viewpoint, they also allow readers to respond and comment (Ojala, 2005), creating a dynamic context (Klamma, Cao, and Spaniol, 2007), and a collective viewpoint.

Scholarly blogging has been studied by Kjellberg (2009), revealing that there are diverse aims with a scholarly blog. Mainly it is a means of informal discussion of research. At the same time there are professional aims including disseminating results. Kjellberg (2009) shows that the genre of research blogs are difficult to limit to a specific category. Blog technology affects the form and, at the same time, the content of the blog is highly interactive with its context. Comparing scholarly blogs to more formal formats of scholarly publications, blog posts can be defined as papers while the whole blog is comparable to a journal. But they are much more informal in their content.

A Wikipedia article is a good example of the shift of academic writing. Jones (2008) underlines the fact that because a Wikipedia article is constantly editable the text has no clear final stage or state. These articles exist in a state where they are continuously changing. The revision process also makes the development of a wiki text very difficult to follow. An article can be downloaded and revised offline, meaning there is no access to revision practices. This also has implications for how quality is established. The level of experience of the editors is unknown, as well as the revision process. Still, open source collaboration seems to generate a good level of quality knowledge. Wiki writing is often highlighted as a great example of collective intelligence. However, there is a fear of quality control in this context. There are traditionally many mechanisms for quality control concerning research and these are most clearly defined for scientific journals. The informal ways of communicating are rapidly growing, shaping uncertainty about quality control (Meadows, 2003). But wikis are not without writing rules and structures and it is important to learn more about these processes. It is of value for researchers to learn more about quality writing in different writing environments (Jones, 2008).

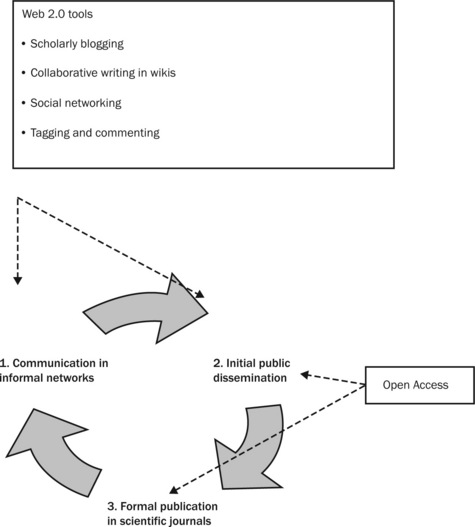

So, it can be concluded that there are many features in Web 2.0 supporting knowledge work which is an important part of the researcher’s task. At the same time there is a need for a critical view and to resist adopting them to automatically solve collaborative issues. The fact that the expertise is flattened may undermine the basis of quality assurance as the knowledge content is constantly unstable. However, having said that Web 2.0 brings opportunities and that there is a need for a critical view, it is clear that it will have great effects on and implications for how we share and gather knowledge and also how we look at the scientific system. Web 2.0 is believed to have implications for the way research collaboration will be conducted across various communities, groups, discourses, and regimes in the academic context. Earlier this was the remit of scientific institutions while we today believe increasingly that the world is of our own making (Schiltz, Truyen, and Coppens, 2007). Web 2.0 brings new dimensions to scholarly communication. It seems to have a rather big impact, especially affecting the initial stages. Web 2.0 leads to growing informal communication about research ideas and initial results (see Figure 10.2).

The different parts of social and interactive communication related to scholarly communication will affect the scholarly communication cycle shown in Figure 10.2 also in ways other than how the initial ideas are communicated and in what forms. There will be more linkages to larger networks in all stages, making the circle more open and diverse. The formal structures are integrated with more informal structures and the process will probably be more blurred and more ambiguous. Networking blurs the traditional division of formal and informal communication. New flexibility in scholarly communication will probably grow in the future (Meadows, 2003). At the same time social media make the process richer and more integrated.

Although the main emphasis is on communicating initial stages the presence of social media will also affect how we write about science. Web 2.0 will encourage revision of traditional conceptions of what constitutes scientific information. Open access and open content means gaining access to knowledge when needed. Knowledge is constructed on demand (downloadable beliefs). Scholarly communication is no longer a linear and hierarchical process with the notion of accumulating knowledge but about circularity and evolution. Social software affects social knowledge while Web 2.0 tools enable group interaction, being simple to use and enabling groups to self organize (Schiltz, Truyen, and Coppens, 2007).

Developing academic library services towards scholarly communication 2.0

Scholarly communication is moving towards a less linear and hierarchical process and the notion of cumulating knowledge is no longer so clear. Through open source techniques a new form of writing practice is emerging (Jones, 2008). This development has implications for university libraries as it becomes an integrated part of research work and scholarly communication. Already digital libraries have shortened the distance between author and reader as they facilitate direct involvement in the dissemination of information (Fox and Urs, 2002). The development of Web 2.0-based services that involve users in the production of content (Benson and Favini, 2006; Bearman, 2007; Coombs, 2007) will alter the whole picture of scholarly communication further.

In order to respond to these new modes of information behaviour the libraries have developed the notion of Library 2.0, mainly in the public library context. Library 2.0 is a term introduced by librarian Michael Casey in 2005 and it comprises user-centered change. It highlights a library environment which encourages constant change and user participation in the creation of physical and virtual library services (Casey and Savastinuk, 2006; Widén-Wulff, Huvila, and Holmberg, 2008). It has been noted that libraries have already adopted several of the Web 2.0 tools to extend their missions of service, stewardship, and access to information. Blogs are used to market new materials and resources, to announce events and to share information. Instant Messaging is used as a mean of providing virtual reference services. Librarians use social networking sites, such as Facebook, to interact with students, answer questions, and provide information about library services. Libraries are also offering Rich Site Summary (RSS) services, which offer users the ability to ‘subscribe’ to catalogue additions and news from the library (Stephens and Collins, 2007). All these features of Web 2.0 in libraries could be signs of a shift in academic libraries towards an open framework for library communication or hyperlinked library in line with a Library 2.0 philosophy of open and participatory library services (Stephens and Collins, 2007).

A definition that focuses the shift towards interactivity and captures the different components and the essence of Library 2.0 is presented by Holmberg, Huvila, et al. (2009). They propose a holistic definition of Library 2.0 in order to respond to the user expectations emerging from the social web. The definition consists of seven building blocks (Figure 10.3) with interactivity as the cornerstone of the whole Library 2.0 development.

Figure 10.3 Building blocks of Library 2.0 (Holmberg, Huvila, et al., 2009)

Library 2.0 is a change in interaction between users and libraries in a new culture of participation catalysed by social web technologies. (Holmberg, Huvila, et al. 2009)

What does this shift in scholarly communication mean for academic libraries? Although Library 2.0 has been acknowledged by both librarians and researchers in library and information science (LIS), few actual studies have addressed Web 2.0 resources and their use in the university library context. Mainly the attitudes among librarians have been studied, showing that there is an awareness of social media and the most positive think that social networks, for example, are kinds of virtual extensions of the campus and library services, fostering collegiate bonds and social identity (Charnigo and Barnett-Ellis, 2007).

There are two sides of the development of library services in the research library context. First of all it must be remembered that social media is built on individual initiatives, and the motivation for using social media in academic writing and research dissemination is based on individual scholars’ interest in participation and interactivity. This process cannot be managed by another party such as the library. On the other hand there is an important role for the libraries to develop the awareness of the possibilities social media can bring to scholarly communication. The development of user education and improvement of media literacy among scholars, especially social media literacy, would be an important aim for academic library services. The academic library could foster an awareness of social software and tools which can be used in the scholarly communication process. Relevant tools and the use of them could be part of user education. It has been shown that the Web 2.0 tools bring new dimensions to networking, informal collaboration, writing, and dissemination.

Another important question for academic libraries is how to define research dissemination and contents produced through social media. Are scholarly blogs part of scientific publication and should they be integrated into the library’s digital collections? How could the library organize contents produced through social media? There are examples of digital collections that are also open for commenting and tagging, which is a part of integrating Web 2.0 in library services. But even if we decide that contents produced through blogs, wikis, social networks, etc. should be organized into digital collections, there are difficult questions about the deposit of electronic information, both legal and technological.

Scholars who are active producers through social media expect interactivity and participation also of library services. Those scholars who are not active may be interested in learning these tools. To meet the different user needs the main focus at this point would be to develop user education integrating the building blocks of Library 2.0 (Figure 10.3).

Conclusions

In this chapter scholarly communication is discussed through the lens of Web 2.0, the social web. Scholarly communication has long traditions with some important turning points over the last few years. The amount of electronic publications has had a great impact on the process. Also the availability has affected scholarly communication and we expect to get knowledge when it is needed. Now the social and interactive web is expected to affect the scholarly communication process where research dissemination becomes more open and interactive and constitutes part of a much larger public than earlier.

Scholarly communication is a social process where social media comes as a natural tool for managing this process even more effectively. Web 2.0 could initiate a new way of scholarly communication and collaboration. In other words, we envision a change in the way university researchers view and enact knowledge sharing as a collaborative activity both offline and online. New modes of scholarly communication are emerging: commenting practice, networking, sharing ideas to a large public over several networks, and collaborative writing. However, old structures will also remain and scholarly communication is mainly enriched by social media at this point.

There are a number of benefits, challenges, and reasons for critical thinking. Social software is technically not challenging, and contributing to a blog or wiki promotes collaboration by merging fragmented knowledge into more usable entities and easily accessible data (Hasan and Pfaff, 2006). However, this is also a challenge to the quality assurance of the information produced. Web 2.0 techniques also demand a huge amount of motivation from the individual to be able to adapt to the interactive tools. Trust is an important enabler to both motivating and using social technologies.

Scholarly communication is challenged by Web 2.0, which promotes the informal elements. Social media are a tool to reach the more formal sources of research dissemination. There are many ways to connect and interact with other researchers with similar interests and contribute ideas to a larger public. What is the role of academic libraries in this context? Or do they have a visible role? Academic libraries are important mediators of scholarly publication and important parts of the whole scholarly communication. With new modes of scholarly communication the library services also need to shift towards interactivity and participation. New skills are needed among both librarians and scholars. User education becomes even more important with new elements of social media literacy. Digital collection management and the question of whether the contents of social media should be part of the digital collections will be important challenges in the future.

References

Avram, G. At the crossroads of Knowledge Management and Social Software. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management. 2006; 4(1):1–10.

Bearman, D. Digital libraries. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST). 2007; 41:223–272.

Benson, A., Favini, R. Evolving the Web, evolving librarian. Library Ht Tech News. 2006; 23(7):18–21.

Björk, B.C. Open access to scientific publications – an analysis of the barriers to change. Information Research. 9(2), 2004.

Borgman, C.L. Digital libraries and the continuum of scholarly communication. Journal of Documentation. 2000; 56(4):412–430.

Brady, M. Blogging: personal participation in public knowledge-building on the web. Colchester: University of Essex, Chimera Institute for Social and Technical Research; 2005.

Casey, M.E., Savastinuk, L.C. Library 2.0: service for the next- generation library. Library Journal. 2006; 131(14):40–42.

Castells, M. 1999Informationsâldern: ekonomi, samhälle och kultur. Daidalos: Göteborg, 2000. [Bd 1–3].

Charnigo, L., Barnett-Ellis, P. Checking out Facebook.com: the impact of a digital trend on academic libraries. Information Technology and Libraries. 2007; 26(1):23–34.

Coombs, K.A. Building a library Web site on the pillars of Web 2.0. Computers in Libraries. 27(1), 2007.

Craig, E.M. Changing paradigms: managed learning environments and Web 2.0. Campus-Wide Information Systems. 2007; 24(3):152–161. [2007].

Dahlgren, P. Internetaldern. In: Dahlgren P., ed. Internet, medier och kommunikation. Studentlitteratur: Lund; 2002:13–38.

Fox, E.A., Urs, S.R. Digital libraries. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST). 2002; 36:503–589.

Graham, T.W. Scholarly communication. Serials. 2000; 13(1):3–11.

Gray, K., Thompson, C., et al. Web 2.0 authorship: issues of referencing and citation for academic integrity. Internet and Higher Education. 2008; 11:112–118.

Hall, H., Davison, B. Social software as support in hybrid learning environments: the value of the blog as a tool for reflective learning and peer support. Library & Information Science Research. 2007; 29:163–187.

Hall, H., Widén-Wulff, G. Social exchange, social capital and information sharing in online environments: lessons from three case studies. In: Davenport E., ed. From information provision to knowledge production. Oulu: University of Oulu; 2008:73–86.

Halliday, L. Scholarly communication, scholarly publication and the status of emerging formats. Information Research. 6(4), 2001.

Hasan, H., Pfaff, C.C. The Wiki: an environment to revolutionize employees’ interaction with corporate knowledge. Sydney, Australia: OZCHI; 2006.

Holmberg, K., Huvila, I., et al. What is Library 2.0? Journal of Documentation. 2009; 65(4):668–681.

Jääskeläinen, P., Savolainen, R. Competency in network use as a resource for citizenship: implications for the digital divide. Information Research. 8(3), 2003.

Jones, J. Patterns of revision in online writing: a study of Wikipedia’s featured articles. Written Communication. 2008; 25(2):262–289.

Katz, J.E., Rice, R.E., Aspden, P. The Internet 1995–2000: access, civic involvement, and social interaction. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001; 45(3):405–419.

Kjellberg, S. Scholarly blogging practice as situated genre: an analytical framework based on genre theory. Information Research. 14(3), 2009.

Klamma, R., Cao, Y., Spaniol, M., Watching the Blogosphere: knowledge sharing in the Web 2.0ICWSM 2007. CO: Boulder, 2007.

Meadows, J. Scholarly communication. In: Feather J., Sturges Paul, eds. International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science. London: Routledge; 2003:565–567.

Miller, P., Web 2.0: building the new library. Ariadne. 2005. [(45)].

Notess, G.R. The terrible twos: Web 2.0, Library 2.0, and more. Library Journal. 30(3), 2006.

Ojala, M. Blogging: for knowledge sharing, management and dissemination. Business Information Review. 2005; 22(4):269–276.

O’Reilly, T. What is Web 2.0: design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. 2005 Available at, (accessed March 19, 2010) http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

Schiltz, M., Truyen, F., Coppens, H. Cutting the trees of knowledge: social software, information architecture and their epistemic consequences. Thesis Eleven. 2007; 89:94–114.

Schmidt, K.D., Sennyey, P., Carstens, T.V. New roles for a changing environment: implications of Open Access for libraries. College and Research Libraries (September). 407–16, 2005.

Stephens, M., Collins, M. Web 2.0, Library 2.0 and the Hyperlinked Library. Serials Reveiw. 2007; 33(4):253–256.

Widén-Wulff, G., Huvila, I., Holmberg, K. Library 2.0 as a new participatory context. In: Pagani M., ed. Encyclopedia of Multimedia Technology and Networking. IGI Global: Hershey; 2008:842–848.

Widén-Wulff, G., Tötterman, A.-K. A social capital perspective on collaboration and Web 2.0. In: Dumova T., Fiordo R., eds. Handbook of Research on Social Interaction Technologies and Collaboration Software: Concepts and Trends. Hershey: PA: Information Science Reference; 2009:101–109.