Towards a General Theory of Public Transport Network Planning

The Way to Cork

A few years ago, an Australian newspaper published a cartoon satirizing economists. A stereotypically pointy-headed male was staring in rage at some example of successful government enterprise, shouting: ‘It might work in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory!’

Urban public transport seems a bit like that cartoon. The success stories reviewed in this book rely on measures condemned by the conventional wisdoms of neo-liberal transport economics: high transfer rates, central planning, government monopolies, cross-subsidization – and congestion instead of road pricing. Conversely, public transport systems that follow the conventional wisdoms have failed, from England to the Antipodes.

But the cartoon economist is right on one point at least. The conflict between theory and successful practice does need to be resolved. We need to understand not only what works, but why it works, if we are to apply the lessons learned from successful public transport systems to cities where transit is failing.

Graeme Davison recounts the old story of the motorist travelling in rural Ireland, who stops a grizzled local and asks the way to Cork. After a long pause, the oldtimer scratches his head and says: ‘Well, if I wanted to go there, I wouldn’t have started out from here.’1 Most transport analysts agree on the desirability of moving beyond the automobile age, but are not convinced that the shift is achievable: even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is daunted by the challenge, as we saw in Chapter 3.

To re-state the central problem, public transport uses urban space and environmental resources more efficiently than the car if it can attract people with different trip origins and destinations to travel together. This task becomes more difficult as origins and destinations disperse, which is exactly what is happening almost everywhere in the world. Trip origins are spreading, as suburbanization lowers region-wide population densities; trip destinations are less concentrated, as the share of jobs and retailing in central business districts (CBDs) falls; traditional peaks are spreading, as working and shopping hours are deregulated.

The result is that public transport is usually infrequent and unattractive, poorly patronized and heavily subsidized. Attempts to improve services will often seem like throwing good money after bad: some additional patronage may be attracted, but not enough to fill the extra seats provided. So subsidies rise, cost-recovery falls, and greenhouse emissions per passenger increase until eventually – as we have seen with buses in the US and Melbourne – there is no advantage over travel by car.

The key to the dilemma is elasticity of demand, the economist’s term for the way demand for a commodity changes when its price or quality changes. An elasticity of 0.5 means that a 10 per cent change in, say, the price will produce a 5 per cent change in demand. Most research into elasticities of demand for public transport has produced figures well below one, with typical figures around 0.2 for fares and 0.5 for services.2 This means that patronage changes more slowly than the rate at which services or fares change. Since cutting fares and adding services is expensive, revenue from the new passengers is unlikely to cover costs. Therefore, the only way increased service can be sustained appears to be through alternative means of provision, such as minibuses or ‘para-transit’, leading us back into the realm of market-based solutions.

There must be something wrong with the studies of demand elasticities, at least for service levels, because they are flatly contradicted by real-world experience. Successful public transport systems offer higher service levels than unsuccessful ones operating in comparable environments, but usually have higher, not lower, occupancy rates. Bus services and occupancies are both better in London than the deregulated British cities; the same applies when Toronto is compared with Melbourne, and when Zurich and Schaffhausen are compared with just about anywhere.

So what’s the explanation? To answer this, we must leave the road to Cork and visit another city, this time an imaginary one called Squaresville. I discussed Squaresville in 2000 in A Very Public Solution, and Gustav Nielsen, now of Norway’s Institute of Transport Economics, developed it in his 2005 HiTrans manual.3 I hope readers familiar with these books will forgive another visit, because it provides the key to understanding how low elasticities of demand can be overcome, and why expanding services need not lower occupancy rates.

The Way to Squaresville: Dispersed Cities and the Network Effect

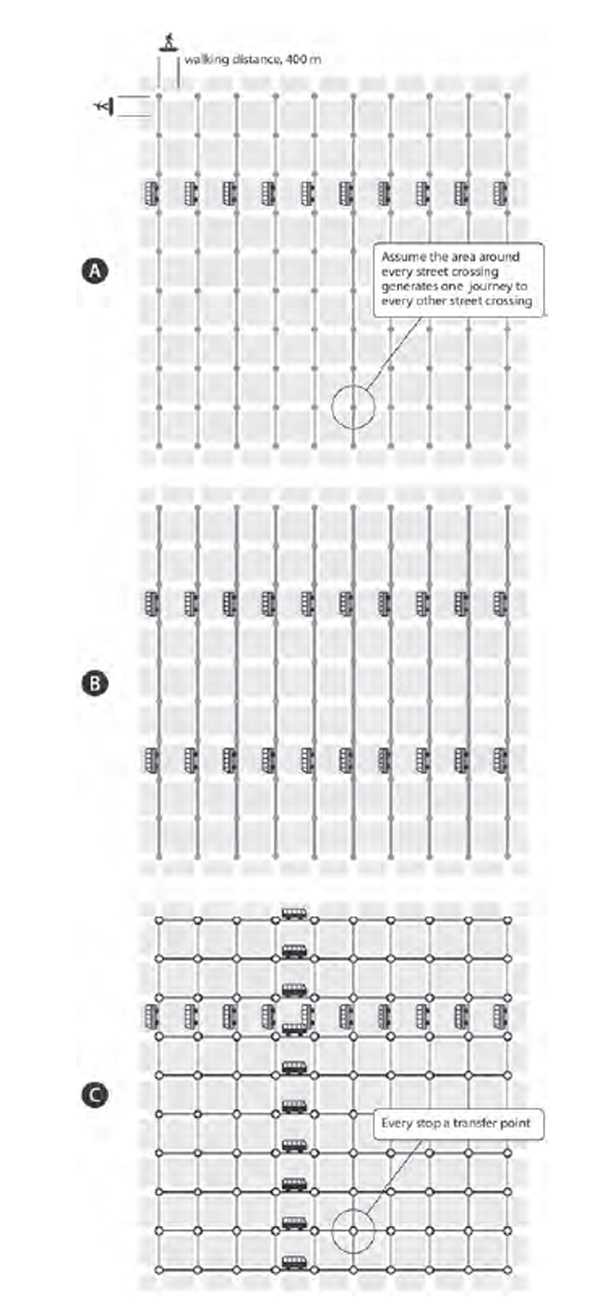

The hypothetical city of Squaresville is a worst-case scenario of urban dispersal, illustrated in Figure 9.1A. It will be familiar to readers of Great Cities and Their

Sources: Mees (2000, p140); Nielsen (2005, p86).

Figure 9.1 ‘Squaresville’ and the network effect

Traffic, as it is based on Thomson’s dispersed ‘full motorization’ archetype of city development.4 The city has a grid road network, with ten north–-south and ten east–west roads, at intervals of half a mile or 800m. Travel patterns are completely random, with no dominant pattern of movement. Each of the city’s 100 square blocks produces 100 trips a day: one internal trip (made on foot), and one external trip to each of the 99 other blocks of the city – giving 9900 external trips in total.

Squaresville has ten bus routes that grew up in a free-market environment, with each operated by a different firm. There is one route along each north–south road, reflecting a past era when this was the dominant pattern of movement (Figure 9.1A). This means that each resident of Squaresville has a bus within 400m walking distance, but can only reach the nine other city blocks lying along her or his bus route, giving access to 900 daily trips out of the total of 9900. Assume that public transport attracts a third of the trips it can theoretically serve; this gives a total of 300 trips (a third of 900), or a city-wide mode share of only 3 per cent (300/9900).

Now, imagine that the government of Squaresville wants to do something about the low rate of public transport use in the city. It pays the bus operators to double service frequencies on Squaresville’s ten bus routes (Figure 9.1B). With a typical demand elasticity of 0.5, this would increase patronage by half, to 450 trips per day or 4.5 per cent of the market. Occupancy rates will fall, since patronage has grown more slowly than service levels, and fare revenue will not cover the extra costs. Subsidies will rise, cost-recovery will worsen and so will greenhouse emissions per bus passenger. Public transport is still of marginal importance, but it has become less efficient in economic and environmental terms.

Imagine instead that the additional buses are used in a different way. Ten east–west routes are introduced to complement the ten existing lines and create a grid network, as shown in Figure 9.1C. The number of trips served directly doubles, to 1800, but by transferring between routes, passengers can now access the entire city, so the network also serves the remaining 8100 trips. Squaresville’s planners do everything possible to make transfers convenient, providing integrated fares, convenient facilities and coordinated timetables. But since so many transport analysts say that passengers dislike transferring, let’s assume that the mode share for trips requiring a transfer is only half that for direct trips, that is one-sixth. So the total number of public transport trips is one-third of 1800 plus one-sixth of 8100, giving a total of 1950.

Under the second model of service provision, public transport’s mode share has jumped dramatically, from 3 to 20 per cent. Service has increased 100 per cent, but patronage has grown 550 per cent, giving an elasticity of 5.5. Increased revenue would more than cover the costs of the additional service and occupancies would rise substantially, reducing subsidies and greenhouse emissions per passenger.

Although Squaresville is not a real city, it illustrates why real cities with integrated public transport networks can have their cake and eat it too, combining high service levels with high occupancies and high efficiency. It also illustrates why uncoordinated service additions, such as those seen early on in deregulated English bus systems, can lower efficiency. The elasticity of demand for service additions doesn’t have to be less than one if the new services are added in a way that serves new trip demands by creating a network.

Significantly, this ‘network effect’ becomes stronger as travel patterns become more dispersed: in a hypothetical city where all trips are made to a single centre, there is no network benefit at all. This contradicts another arm of the conventional wisdom in transport economics, which assumes that public transport is only likely to be a natural monopoly (see Chapter 5) in dense, centralized cities where strong demand produces economies of scale. The network effect is an example of ‘economies of scope’ and, as Thomson’s study of Pacific Greyhound in Chapter 5 showed, it applies in the opposite situation – namely where demand is weak and dispersed. In a more recent paper, Thomson argues that US cities that have followed a similar strategy, turning radial systems into multi-destinational networks, have achieved better patronage and efficiency outcomes than those that concentrated on providing transfer-free trips to a limited range of destinations.5

Australians get the opportunity to see the network effect in action each time they travel to Europe. At the time of writing, it is not possible to travel directly from Australia to any European airport other than London Heathrow. To reach Paris, Berlin or Rome, Australians must transfer, either at London or at an intermediate hub like Singapore or Dubai. I once spent five hours waiting for connections at Singapore at around 2:00 am and did not enjoy the experience! But the demand for travel between Australia and any other European port is so thin that direct services cannot be economically supported, unless they are to run only weekly or fortnightly. Nobody will wait a week for a direct service when there are competing daily services with transfers, so no direct trips are provided. There were once infrequent direct services between Australia and other European cities, but this was at a time when fares were so high that airlines could run half-empty planes and still make money. The transfer at London or Singapore is one of the costs of the dramatic fall in real airfares in the last three decades, but it has also allowed Australians easier access to a larger range of European cities. For example, the quickest route to Copenhagen is through Singapore, rather than London.

In the airline industry, network planning has enabled firms to connect a wider range of origins and destinations, while at the same time increasing occupancy rates and lowering fares. In urban public transport, the network effect also allows the apparently impossible to be achieved: genuine networks can serve a wider range of destinations, increase frequencies and operating hours, and improve occupancies – thereby lowering pollution and subsidy levels per passenger.

Network planning also changes the rules of the debate between rail and bus enthusiasts. It allows buses to provide the high service levels and easy-to-understand route structures that were once regarded as the exclusive property of heavy or light rail – as Ottawa, Curitiba and Schaffhausen, among others, have demonstrated. But the network effect also allows high-quality rail to be provided when regional populations are lower or more thinly spread than in the big, dense cities which were once believed to be the only places suited to it – Toronto, Vancouver and suburban Zurich are cases in point.

The network effect even offers a solution to another dilemma faced by transit planners, namely guessing where passengers want to go. One of the traditional arguments for competition in public transport has been that public authorities will be insufficiently dynamic to track changes in travel patterns and respond with new service offerings. But with a full network provided, the passengers themselves will answer this question by using transfers to reach new destinations as they arise, just as motorists use a road network to make new trips. And provided trends in patronage are monitored properly, the agency in charge of tactical planning can track changes and respond appropriately. A good example is the Translink bus network in the City of Vancouver, which operates as an interconnecting high-frequency grid. ‘B-Line’ express bus service is being introduced progressively on key corridors, which are easily identified as those with the highest and fastest-growing patronage. The busiest B-Line services are in turn being replaced by extensions of the regional light rail network.

Given its obvious advantages, it is often asked why network planning requires public control to succeed. Why don’t private transit firms adopt it voluntarily, in order to reap the benefit of increased demand and higher occupancies? The answer is that networks require cross-subsidy. Because real cities are not exactly like Squaresville, demand is not evenly dispersed: some routes and periods of the day are more profitable than others, but all must be run at high standards to create a functioning network. Under a genuinely privatized system, who will volunteer to run the loss-making routes that, by creating a network, increase profits on the strong lines, most of which are operated by rival firms? The answer is, nobody. No rational private firm will be the ‘sucker’ who bears a loss so other firms can make greater profits.

We saw this in Foz do Iguacu, where the city council provided the infrastructure, but not the organizational arrangements, for a Curitiba-style network. The city’s bus firms have stuck to serving profitable corridors, and shown little enthusiasm for integration of fares or services. And in Leeds, as we saw in Chapter 5, a major bus operator said it would ‘not condone or support’ integration with rail. The British bus industry is happy with deregulation: it delivers handsome profits from the large and growing subsidies the government provides for managing decline, all with a minimum of interference – especially from those pesky passengers who are always bothering public operators in London and Europe with demands for high-quality services.

Creating a network is a classic example of a ‘collective action problem’, a situation in which individuals acting rationally produces a collectively irrational outcome. Another name for this phenomenon is market failure.

Public transport in dispersed cities is a natural monopoly, because only a single organization can carry out the tactical planning necessary to provide an integrated network of routes and services. Without network planning, adding services is likely to reduce efficiency. In an environment like Hong Kong or Manila, wasteful competition of this kind can be sustained financially, but it cannot be afforded where demand is thin. And thinly spread demand is precisely the transport pattern that is growing rapidly as cities in virtually all developed nations disperse. In other words, it is the demand public transport needs to meet if we are to move beyond the automobile age.

Now we have the answer to the contradiction between orthodox transport economic theory and the real world. The theory is wrong, at least in the case of urban public transport. The network effect produces economies of scope that make public transport a natural monopoly, and the more dispersed demand is, the stronger the effect is.

This in turn explains why only public transport systems in which tactical planning is handled by a central public agency are succeeding in competing with the car. Deregulation and franchising, which leave tactical planning to the market, are not able to create the network effect, and are only sustainable in markets where there is no serious competition from private transport: large, dense cities, or places where low incomes still limit car ownership.

The lesson is being learned by more and more cities, generally as a result of the work of practising transport planners rather than academically trained transport economists. The Verkehrsverbund can now be found in most German and Austrian urban regions; Madrid has had an equivalent regional organization since 1986, and has seen a sustained increase in ridership; the other Swiss cantons have adopted different organizational forms and terminologies from Zurich, but regional and national network planning now covers the entire country. Hourly pulse-timetabled rail and bus services reach into remote corners of the sparsely populated canton of Graubunden, enabling the Swiss National Park – which has a population density of zero – to promote public transport as the preferred form of access.6

And the lessons are spreading beyond Europe. Singapore’s Land Transport Authority observes that while the rail system is popular with locals and visitors, buses are a constant source of public dissatisfaction, because they are ‘planned by the [private] operators based largely on commercial considerations’. To create an integrated system, ‘LTA will take over central planning of the bus network’. Buses will be reoriented to feed, rather than duplicate, the rail system and multi-modal fares will be introduced. This will require a change from the current monopoly franchise system to one in which bus firms tender to become sub-contractors on the London model.7

Singapore has discovered the lesson behind public transport success in Toronto, Vancouver, Ottawa, Curitiba, Zurich, Schaffhausen and other cities – and corresponding failure in places like Melbourne and English cities. To operate effectively and avoid market failure, a natural monopoly like urban public transport must be planned by a single public agency.

Meanwhile, In the Bunker

This trend has barely registered in much of the anglosphere, and other places where the influence of free-market ideology remains strong. The failure of deregulation is eloquently attested by the British experience, but also by the success of developingworld cities like Bogota, which have abolished it. Now that New Zealand, the World Bank and the European Commission have abandoned free-market public transport, the notion remains the sole preserve of a small cell of British fundamentalists holed up in Whitehall and free-market think-tanks. Unfortunately, the British government still takes its advice on transport policy from within this ideological bunker.

Britain’s oldest free-market think-tank, the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), was still lauding Manila’s jeepneys as recently as 2005, in a booklet celebrating both the 20th anniversary of deregulation and the work of the economist John Hibbs, a driving force behind the original policy.8 After two decades, there is ample evidence available on trends in patronage and subsidies in the deregulated systems and London, but not one of the booklet’s 117 pages refers to any of this evidence. The argument is purely rhetorical – but it worked, as the UK Department for Transport backed a continuation of deregulation the following year (see Chapter 5).

Hibbs’ IEA essay did cite a single piece of data: apparently, bus usage in Cambridge increased by 45 per cent in only three years.9 Hibbs did not specify the years in question or provide a source for the claim, but Cambridgeshire County Council, the organization responsible for public transport in the region, did record a 14 per cent increase in bus patronage over the three years to 2005.10 In that year, the county’s 570,000 residents made 17.3 million bus trips between them, around 4 million more than were made by the 44,000 residents of Schaffhausen. This represents 30 bus trips per person per year, a tenth the rate of Schaffhausen and lower even than Los Angeles or Auckland. At the 2001 census, just under 7 per cent of county residents travelled to work by public transport, with 3.8 per cent using buses and 2.9 per cent travelling by train (mainly to London): 73 per cent went by car. The bus, train and car shares for Cambridge City were 5.7, 3.4 and 45 per cent, the lower car figure resulting from high cycling rates.11 If these figures represent success for deregulated public transport, then the case for planning is conclusively established!

The University of Sydney’s David Hensher was until recently the most prominent service integration sceptic, reluctant to concede even the need for multi-modal fares. Since only 2 per cent of bus trips in Sydney involve transfers, he argued, the absence of multi-modal tickets will not concern the great majority of passengers. But this puts the cart before the horse: the low transfer rate in Sydney is caused by the lack of service integration, including the absence of integrated fares. Hensher’s proposed alternative of ‘cross-regional services … in which a passenger can travel on a single mode/operator service without transfers’12 is a chimera. In dispersed cities, travel patterns are too diffuse to allow such low-demand services to be provided economically, even if operators were able to guess the right origins and destinations to connect. In our hypothetical city of Squaresville, at least 160 routes would be needed to directly link all origins and destinations, compared with 20 using the network effect.

But even Hensher may be changing his views. His most recent paper advocating busways, published in late 2008, attributes the success of Curitiba and Bogota to integration and networking, including ‘a hierarchy of feeder and trunk routes, with almost seamless transfer points.’13 Interestingly, Hensher’s paper appeared in a volume published by Singapore’s Land Transport Authority (LTA), which as we have seen, is also moving towards network planning.

The concession or franchise system retains more supporters than deregulation. It was envisaged as a compromise between the free market and central planning and, like so many compromises, has combined the worst features of both alternatives. John Hibbs is right when he says that franchising requires just as much ‘top-down public control’ as a system actually run by a public agency.14 But (and this is my observation, not Hibbs’) public control under the concession system is exercised without the traditional safeguards needed to keep public officials efficient and even honest. Officials must judge ‘beauty contests’ involving packages of heterogeneous and often intangible issues, ranging from cost to the slippery concept of innovation. There is no obviously correct answer, and franchisees have a strong incentive to engage in tactical behaviour like ‘low-balling’, distracting attention from the real story with attractive-sounding innovations like wind-powered trams and buses that run on canola oil (don’t laugh: Melbourne proudly boasts both of these).

Over time, multinational firms that specialize in bidding for franchises will become experts at manipulating beauty contests, since they have wider experience and stronger incentives to win than the government officials acting as judges. And worse still, the beauty contest judges are insulated from the consequences of their mistakes – by legal complexity, secrecy, ‘commercial-in-confidence’ provisions, but also by an ability to blame the franchisees for any problems. Such a system creates a strong likelihood that bad decisions will be made, and then covered up rather than openly acknowledged.

The result is a textbook case of an environment in which problems ranging from poor performance to ‘regulatory capture’ to outright corruption can flourish.

The British rail system seems to be an example of poor performance. The Office of Rail Regulation, which succeeded previous bodies such as the Strategic Rail Authority, is a unit of the Department for Transport. The office and its predecessors have maintained more independence from the franchisees they regulate than their counterparts in Melbourne. Independent assessments of UK rail franchising have delivered verdicts ranging from total disaster through to the proverbial curate’s egg, one of the more optimistic concluding that it has avoided the worst results of bus deregulation and even produced modest innovations in fare discounting schemes.15 But nobody can name a genuine innovation in service of the kind seen in Zurich’s suburban network and across the Swiss national rail and Postbus systems. At a time when the inhabitants of Switzerland’s cities – which would only count as towns in the UK – are looking forward to 15-minute all-day service frequencies across a nation-wide integrated network, residents of big British cities pay much higher fares for less frequent, poorly coordinated services.

Trips across different British rail operators’ territory involve a bewildering array of timetables and fare types, with even the amount of time one must leave for connections varying according to the operator involved. Here is part of the valiant attempt by National Rail, the marketing umbrella group established by the British rail firms, to explain:

Example. At Barnham a different minimum connectional allowance applies for Train Operator SN. This means that if your journey involves changing between two trains both of which are operated by SN, you need only allow 2 minutes. If, however, one or both trains are provided by any other Operator then the minimum of 5 minutes (as shown after the station name) applies.16

Multi-modal journeys involving rail and bus are even more trying, and are only attempted by intrepid souls in whom the spirit of British explorers from bygone centuries still lives. An indication of the dismal state of affairs is unwittingly provided by the radical journalist George Monbiot in his best-selling, and otherwise excellent, climate change manifesto, Heat. Rather than recommend the multi-modal solution which has proven effective in Switzerland, Monbiot champions a ‘visionary’ proposal by an economist to cater for inter-city travel with swarms of buses operating on motorways, based at terminals on the outskirts of urban areas. Inter-city public transport in Britain is so dysfunctional that even radicals apparently can’t envisage practical solutions.17

As the 2009 recession began to adversely affect the demand for travel, British franchisees – who were happy to take the credit for patronage rises during the economic boom – signalled that they would require large increases in previously agreed subsidy levels.

At the other end of the spectrum, corruption of city officials by tramway franchisees produced a cavalcade of scandals that led to the US reform movement of the early 20th century (and also, as we have seen, an industry that was bankrupt even before the car began to offer serious competition). Melbourne since 1999 and Curitiba before the mid-1980s provide examples that are part-way along the spectrum, with Melbourne offering a striking instance of regulatory capture so complete that the operators and regulator actually boast about being ‘partners’.18

Creating an Effective Public Transport Agency

The market cannot deliver effective urban public transport, especially in dispersed cities, but it does not follow that the mere existence of a public agency will solve the problem. We saw in Chapter 5 that support for privatization in the 1980s was influenced by the poor performance of many public authorities in the US and the UK. As Mark Twain discovered on his 1895 visit to Victoria, public operators are perfectly capable of replicating the lack of integration found in market-based systems.

Regional public transport agencies must be dynamic and efficient if they are to succeed in dispersed environments where the car offers real competition. This is partly a question of organizational structure, but culture and history are equally important.

Why were government subsidies for public transport in US cities followed in so many cases by declining operating efficiency rather than radically improved services? Why did the introduction of similar subsidies in Canada only a few years later produce better results?19 An important part of the answer lies in organizational history. Public transport in Canadian cities was taken into public hands earlier than in the US, and in response to disputes about service, rather than bankruptcy. Managers of public systems inherited enterprises that were financially sound and well managed. Most US systems were taken over only after decades of decline in the quality of both management and service. In Canada, government subsidies allowed these efficient public operators to expand into low-density suburbs, replacing private firms, as we have seen in the cases of Toronto, Vancouver and Ottawa. Many US transit systems never had the opportunity to acquire efficient operating cultures, as they were rapidly transformed from failing private firms confined to inner cities to region-wide public agencies charged with serving difficult suburban terrain.

Organizational history also helps explain why buses and rail in London remain poorly integrated, more than seven decades after the establishment of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) may well be the world leader in rail–bus and rail–tram integration, with ‘free-body’ transfers at most stations, where buses, and even trams, arrive and depart from terminals inside the fare gates. One reason for this high level of integration is that the TTC expressly designed its rail system to replace the busiest tram lines and link with the remaining routes. The Zürcher Verkehrsverbund comes from a different history to the TTC, being an umbrella body like the LPTB; however, it was established with the express objective of integrating services and fares.

The London changes of 1933 merged a dozen pre-existing tram, bus and underground operators, who had begun life as competitors. The different entities were rationalized into road transport and railway divisions, unintentionally perpetuating the rivalry. The lack of integration was exacerbated by the decision to keep most surface railways outside the LPTB’s remit.20 Despite the introduction of multi-modal daily and periodical Travelcards in 1981, during Ken Livingstone’s first term as Mayor of Greater London, single, off-peak and some longer-term tickets remain single-mode, while route connectivity and timetable integration remain patchy. The recent ‘London Overground’ initiative to bring some surface railways closer to the service standards found on the Underground is the first big step towards integration in almost three decades.

Public transport organizations in many cities developed inward-looking cultures in the days when low car ownership meant most residents were ‘captive’ to public transport. They concentrated on the relatively simple task of carrying large passenger flows on radial routes, and paid little attention to providing a total service for all needs. With the advent of the car, many such organizations lacked the dynamism to pursue anything more ambitious than the ‘easy option’ of managing decline. A culture developed that Vuchic calls the ‘self-defence of incompetence’.21 He notes that ‘the less competent employees are, the more they resist any changes’, an observation that applies with equal force to public transport agencies as a whole. This problem seems to have been particularly serious in the UK and Australasia before deregulation and franchising, but has not been cured by these measures.

Efficient, passenger-focused agency cultures can evolve from fortunate organizational histories, but usually have to be created. This issue has been poorly understood in many institutional reform exercises, which have assumed that setting up appropriate bureaucratic structures is sufficient. Bad organizational cultures have to be tackled directly, rather than by simply rearranging the same people in different public or private administrative units. This may require new staff at senior levels, the involvement of advisers from outside the organization, and strong leadership from local communities and politicians. This kind of work is difficult but necessary, even if it is more arduous and boring than a constant rearrangement of organizational flow-charts.

One important lesson from all our success stories, even Curitiba, is that transparency and public participation increase the effectiveness of a public transit agency, provided the agency’s staff have enough confidence in their own expertise to engage in genuine public debate. Zurich’s transport planners now agree that the 1960s and 1970s proposals to replace trams with a metro were mistaken: their defeat forced planners to come up with proposals that achieved better outcomes at lower cost. And the same is true of the nation-wide pulse-timetable system that replaced the Swiss Federal Railways’ earlier plans for ‘bullet trains’. Stefan Bratzel’s study of sustainable urban transport success stories in Europe confirms the critical importance of public debate and even conflict in reviving public transport.22

A related success factor in a number of the cities studied by Bratzel has been a productive, although not always harmonious, relationship between ‘town’ and ‘gown’ – one that reached its apogee in Zurich with Professor Kunzi’s move from the operations research programme to the transport ministry (see Chapter 8). The coalition which blocked the city’s 1973 metro proposal was based at the University of Zurich and the adjacent Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, or ETH). Researchers at ETH, in particular, have played important roles in operational innovations on the local and national rail systems, including the current ‘Puls-90’ project, which seeks to increase national rail capacity without substantial new infrastructure by lowering headways to 90 seconds (by contrast, British rail headways are actually widening, as operating practices become steadily more conservative).23

The same phenomenon can be seen on a less intimate level in other successful cities: the ‘freeway revolts’ in Toronto and Vancouver were based at the Universities of Toronto and British Columbia, while UBC staff and students have lobbied for service innovations like B-Line express buses and the U-Pass periodical ticket for tertiary students (see Chapter 12). Unfortunately, this level of positive interaction is quite rare. Most transport researchers concentrate on collation and modelling of aggregate data rather than direct attacks on specific management and planning problems. And in the UK, Canada and Australasia, declining government support has encouraged academics to seek funding from outside sources, making many researchers reluctant to offend potential ‘industry partners’ by criticizing existing practices. The head of the Institute of Transport at ETH Zurich laments the absence of direct financial support from the federal railways, since it restricts the amount of research the institute can conduct. But ‘there are also advantages, because we can focus on “total public transport systems” as a whole.’24

Related to the question of participation is the notion of subsidiarity, or allowing problems to be solved at the lowest level of government consistent with efficiency. Some of the most damaging urban transport decisions, such as British bus deregulation, Melbourne rail franchising and the European Commission’s abortive bid to make franchising compulsory, have been top-down measures imposed by higher-level governments. A strong say for local and regional governments has been critical to all our success stories, even those like Toronto that have relied on higher levels of government for intervention at critical stages. Bus patronage in London took off rapidly once the British government surrendered control to Transport for London (TfL), while the absence of interference from national and state governments allowed Jaime Lerner to revamp Curitiba’s bus system.

Subsidiarity was originally justified as promoting participation, but also efficiency, by preventing the state being ‘overwhelmed and crushed by almost infinite tasks and duties.’25 The benefits of subsidiarity – which is actually listed as a guiding principle in the Swiss and Zurich Cantonal constitutions – can be most clearly seen in the lean, simple organizational structure of the Zürcher Verkehrsverbund (Figure 8.1). The ZVV can focus its energies on the critical tasks of tactical planning and cost-control because it delegates operations to skilled, reliable sub-contractors.

The value of simple organizational structures suggests a cautious approach to a popular recipe for coordination, namely to have the same body in charge of roads and public transport, and possibly even land-use planning. There are examples of agencies that successfully manage roads and public transport – TfL and Vancouver’s Translink are two – but there is a risk of loss of focus. Interestingly, these two bodies both sub-contract much of their service delivery: to private firms in London, and to subsidiary companies in Vancouver. And it is by no means clear that having a single agency responsible for roads and public transport will prevent roads policy undermining sustainable modes: it is more likely to result in a ‘balanced transport’ compromise, in which each section of the agency gets its share of the cake. When the car competes for funds with sustainable modes in a fair, public contest it usually loses, as even Auckland’s transport planners of the 1950s understood.

Who Should Be In Charge?

Agency structures are also important, however, and there is a range of viable options once the failed choices of deregulation and franchising are eliminated. These are strategies 1 to 4 on the continuum discussed in Chapter 5. All of them involve the transit agency taking responsibility for tactical planning, but each deals with operational and strategic issues differently.

Every successful agency must have some common features that seem to be non-negotiable. The agency must have jurisdiction over the entire functional urban area rather than just the central municipality (the lack of this element is probably the key factor holding public transport in Greater Toronto back). It must control overall finances, allowing the pooling of revenue to avoid endless disputes and permit the cross-subsidy that is essential to network planning. Finally, it must be allowed to operate independently of the day-to-day political and media cycle, while being publicly accountable for its performance. This combination is necessary to guard against capture by vested interests (ranging from trade unions to private contractors), encourage efficiency and customer focus, and enable the agency to advocate for adequate funding in the public arena.

The concern for independence is one reason why most contemporary analysts are sceptical about the first option on the continuum, of a government or municipal department. Political interference and bureaucratic remoteness from the consequences of decisions can inhibit efficient and innovative tactical planning. British rail timetables are now planned mainly by the Department for Transport’s Office of Rail Regulation. Franchisees bid to operate services within the constraints of this bureaucratically planned timetable. It is difficult to envisage an environment in which those responsible for timetabling are more remote from the consequences of their decisions – and the results, predictably, are stagnation and even decline in efficiency and innovation.

By way of contrast, the transformation of OC Transpo into a department of the new City of Ottawa appears not to have adversely affected efficiency or innovation. This seems to be due to two key differences with the British experience: first, OC Transpo is a ‘hands-on’ agency that must bear the consequences of its operational decisions; secondly, the Ottawa bus system is much smaller than the UK rail network, and therefore a more manageable size.

The most popular transit agency model is the semi-autonomous public authority: examples include the Toronto Transit Commission, Translink, the Zürcher Verkehrsverbund and Transport for London. Some of these organizations have strong political control: the TTC’s board is made up entirely of elected councillors, while the the Cantonal minister for transport chairs the ZVV board, which also includes local government representatives. Others rely on professional directors of the kind one might expect on the board of a private company: the government of British Columbia recently introduced this system for the Translink board, while TfL’s board, although chaired by the Mayor of London, is mainly made up of professionals.26

The real difference among agencies of this kind is the extent to which they operate services themselves or delegate operations to other bodies, including private firms. Although there is a clear tendency to separate tactical and operational functions, through the ‘federation’ approach of the ZVV or through private contracting, as in London, there remain important exceptions. The TTC serves a larger population than the ZVV and carries more passengers, but performs operations in-house to achieve efficiencies in timetabling and resource allocation that would not be possible with sub-contracting (see Chapter 5). Translink subcontracts all its services, but mainly to subsidiary companies that it owns; some bus services are operated by the City of West Vancouver’s transit department, and the private sector also has a role, mainly in para-transit. As Eliot Sclar reminds us (see Chapter 5), contracting out can save money and simplify workloads in appropriate cases, but when used unwisely, it can increase costs and lower service standards.

One reason for using the federation model instead of a single mega-operator is to simplify the task of unifying different transit systems across an urban region. This is the way the Verkehrsverbund concept developed in Germany, and it may well be the appropriate solution to integrating the efficient operations of the Toronto Transit Commission with the remaining public transport providers across the Greater Toronto Area.

The rule on operations seems to be horses for courses. There is no single correct answer, and the best solution will depend on local conditions, preferably chosen on the basis of a dispassionate comparison of the alternatives, rather than through top-down impositions like compulsory competitive tendering. The only universal principle is that the public body must control tactical planning, which rules out full privatization, whether through franchising or deregulation.

Taking Public Transport Seriously

The other critical factor for public transport agency success is the transport policy environment. If public transport is treated as merely an adjunct to a car-dominated environment, for city commuters and the disadvantaged, or if inadequate funding is provided, or if public transport improvements are constantly undermined by expansion of the competing road system, then no amount of internal effectiveness and innovation will develop an optimal outcome. Effective public transport agencies are most likely to prosper when incentives for sustainable transport are complemented by disincentives for the automobile (see Chapter 3). And while this book argues that the role of urban density, in particular, has been overemphasized, it remains true that land-use planners can help or hinder public transport, particularly through their influence over the location and design of trip attractors such as employment, retailing and services.

If all these elements are in place, the next challenge is to actually design a public transport network that will provide anywhere-to-anywhere travel and reap the benefits of the network effect. Gregory Thompson noted in 2003 that the importance of transfer-based networks is not widely appreciated in the transport planning literature, with the result that little guidance is publicly available on planning such networks. When Gustav Nielsen wrote his HiTrans manuals in 2005, he also found that there was little published material to draw on. Nielsen’s manuals have partly addressed this deficiency, as has Vukan Vuchic’s Urban Transit: Operations, Planning and Economics, also published in 2005. With the exception of these two books, there is no publicly available material on the fundamentals of network planning, so the next chapter will provide a basic outline of the basic principles. Readers wanting more detailed information will find it in Nielsen’s and Vuchic’s books.

Notes

1 Davison (2004, p260).

2 E.g. Ceder (2007, pp327–330); Balcombe et al (2004, chs 6 and 7).

3 Mees (2000, pp138–150); Nielsen (2005, pp84–93).

4 Thomson (1977, ch. 3, esp. p100).

5 Thompson and Matoff (2003).

6 www.nationalpark.ch/snp.html (accessed 30 August 2009); Sorupia (2007, ch. 5).

7 Yam (2008, p7); see also LTA (2008a, pp28–32, 38–40).

8 Hibbs (2005, p72).

9 Hibbs (2005, p65).

10 Cambridgeshire County Council (2005, p25).

11 ONS (2003, p288, table KS15), excluding ‘working from home’.

12 Hensher (2007, p58).

13 Hensher (2008, p27).

14 Hibbs (2005, pp64–65).

15 Nash and Smith (2007), but see also Kain (2007) and Wolmar (2005).

16 National Rail (2008, p6).

17 Monbiot (2007, pp147–154). Monbiot justifies his preference for buses with a table showing that a nearly full coach produces 83% as much greenhouse gas per passenger as a 70% full train. The same figures suggest that if both vehicles were full the emissions per train passenger would be lower. Monboit then suggests adding trainlike on-board facilities to buses (2007, p151), lowering occupancies and increasing emissions per passenger to a level even further ahead of that for trains. But the real weakness with the analysis is that it compares present UK practice on a single-mode basis, rather than assessing the potential of an efficient multi-modal system.

18 Hensher (2007, p36) thinks Melbourne’s regulator was ‘quite possibly’ captured.

19 Frankena (1982).

20 Barker and Robbins (1974, vol. II, ch. XVI).

21 Vuchic (2005, pp316–317).

22 Bratzel (1999).

23 Leuthi et al (2007); see also ‘Padding prevents service improvements’, Modern Railways October 2008, p3.

24 Brändli (1996, p15).

25 Pius XI (1931, par. 78).

26 Vuchic discusses selection of board members at (2005, pp300–301).