In the movie Big, a young boy named Josh makes a wish at a fair-ground machine. Josh wants to be "big," and when he wakes up the following morning his wish has been granted. Josh now dwells in a grown-up body (played brilliantly by Tom Hanks), but he is still the same twelve-year-old kid inside. In his new body, Josh must learn how to cope with the unfamiliar world of grownup relationships, including with his coworkers at a toy company. Josh is great at his new job because, as a real twelve-year-old inside, he is absolutely tuned in to what children want to play with.

Josh's encounters with the tuned out grown-ups are revealing. They are exactly the sorts of discussions we know from experience happen inside most companies:

Paul: (one of Josh's coworkers): These tests were conducted over a six-month period using a double-blind format of eight overlapping demographic groups. Every region of the country was sampled. The focus testing showed a solid base in the nine- to eleven-year-old bracket, with a possible carryover into the twelve-year-olds. When you consider that Nobots and Transformers pull over 37 percent market share, and that we are targeting the same area, I think that we should see one-quarter of that and that is one-fifth of the total revenue from all of last year. Any questions? Yes? Yes?

Josh: I don't get it.

Paul: What exactly don't you get?

Josh: It turns from a building into a robot, right?

Paul: Precisely.

Josh: Well, what's fun about that?

Paul: Well, if you had read your industry breakdown, you would see that our success in the action figure area has climbed from 27 percent to 45 percent in the last two years. There, that might help.

Josh: Oh.

Paul: Yes?

Josh: I still don't get it.

We meet employees like Paul all the time, corporate types who dream up a product based on gut feel and then use data (in this case, focus groups and sales figures for related products) to make him and his colleagues believe his product is a winner. But it is clear from Josh's reaction that nobody actually listened to kids to find out what they might think is fun to play with. If you're in the toy business, your job is to find out how to help kids have fun.

In fact, Josh's opinion alone isn't enough. His company should still get out of the office and go interview other children. Interviewing buyers on their home turf reveals much more about how to develop a product than does merely showing them an "inside-out" product in a focus group.

Of all the causes of tuned out behavior, the most common we've observed is the logical (but incorrect) assumption that, because you're an expert in a market or industry, you therefore know more than your buyers about how your product can solve their problems. It's natural, for instance, for twenty-year auto industry veterans to assume they know more than a hundred mothers do about how to drive preschool-age children around town each day. Too often, this kind of assumption results in poor products, such as those created when Detroit product development experts just design the radio (or keyless entry system, or cupholder layout) that they themselves would want to buy.

When was the last time you bought your company's product?

In the late 1960s, Woodstream Corporation, announced that it had built a better mousetrap.[10]With great fanfare, the company launched the new product into the marketplace, claiming that it was even better than their wooden, spring-based Victor mousetrap, a classic that had sold more than a billion units since the company introduced it in 1890. Alas, the world did not beat a second path to the company's door. The new, "better" mousetrap was a flop, and the company had to revert back to its "old-fashioned" wooden model. A company spokesperson said, "We should have spent more time researching housewives, and less time researching mice." Today, the product that people want to buy—the Victor mousetrap—is still the most recognized brand name in rodent control.

Executives, product development people, and marketers all want to believe that they've got all the answers. They're like the guys at Woodstream Corporation who thought that they could make a better mousetrap because they were the experts. The entrepreneur wants to go with her gut. The product manager wants to recreate a past success. The marketer wants to rely on expensive advertising to buy market share, or to gamble on a huge Time magazine, Wall Street Journal, or Today Show media hit. But these seat-of-your-pants approaches involve much more risk. Going on intuition, buying your way in with expensive advertising, or begging your way in by hoping for media coverage simply does not work as often or as well as being tuned in.

In 1979, the U.S. government introduced the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin.[11] We can imagine the thought process inside the United States Mint: "For our next product, we'll create an exciting new currency option that will cost us less than paper dollars because each one will last longer. And we can honor an American feminist leader at the same time!" This is a classic case of tuned out product development. Instead of solving a buyer problem, the Susan B. Anthony dollar was designed to solve a problem that faced the organization that created it: the United States Mint.

The coin was universally rejected within the first ninety days because it didn't solve any significant existing problems for consumers. On the other hand, it did introduce new problems. In particular, the dollar coin was remarkably similar to the quarter in size and color, confusing the people who used it and making it less likely that they'd want to use it in the future.

Didn't anyone test the coin with consumers? Actually, the government had indeed contracted with a market research firm before developing the Susan B. Anthony dollar. We are told that extensive consumer research indicated the coin would be a miserable failure. However, government officials tuned out, ignored the data, and charged forward because the vending machine lobby convinced the government that America needed a dollar coin. And since the vending machines in operation at the time couldn't, without extensive retooling, accept coins that were significantly larger or different than a quarter, they insisted on the silly size that was so similar to a quarter. The original design called for a hendecagon-shaped edge to the coin, but the vending machine manufacturers protested the 11-sided option. In the end nobody (except for coin collectors) wanted it, so at the end of production, the United States Department of the Treasury was left with hundreds of millions of unused coins in its vaults.

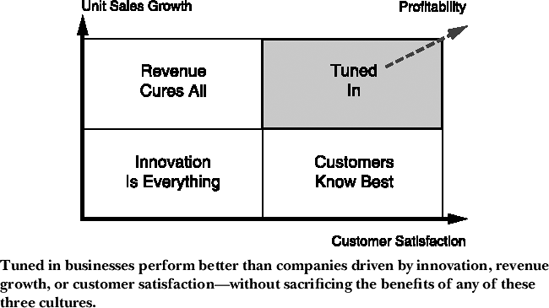

As we've analyzed hundreds of companies to understand the process of becoming (and staying) tuned in, we've determined that most have a single dominant focus that drives their approach to business. Think of it as a "company personality" that determines how an organization structures itself and behaves in the market. The most successful organizations are tuned in. Whenever leaders create products or services—for potential new customers or even entirely new markets—they seek to solve buyer problems first.

However, we have identified three other common organizational cultures. When an organization allows one of these three cultures to dominate, the resulting approach to business is very different from the one we outline in the Tuned In Process:

Innovation Is Everything

Revenue Cures All

Customers Know Best

While most tuned out companies exhibit at least a small amount of each of these driving behaviors, one usually dominates. And the choice directly correlates to their success (or failure). Let's explore each of these in further detail.

Tuned in businesses perform better than companies driven by innovation, revenue growth, or customer satisfaction—without sacrificing the benefits of any of these three cultures.

These days innovation is hot. Check out all the magazine articles, business school courses, and books on the subject and you'll find countless examples detailing how innovation creates breakthroughs. This has led many organizations (start-ups in particular) to focus exclusively on their ability to innovate and to create a disruptive breakthrough that will make them famous. But directionless innovation is a common road to the business scrap heap.

The culture of "Innovation Is Everything" breeds tuned out behaviors. Innovation-driven leaders tend to listen only to themselves, although they do track competitors religiously. These companies fixate on "one-upping" alternative products in the marketplace. And they obsess about who's getting credit for the most clever or unique inventions.

Focusing on "changing the game" is not inherently a bad thing. Some organizations are really good at creating and marketing innovative products—Bose, Nike, and Brookstone are three that come to mind. Unfortunately, what we tend to see more often are companies that innovate for innovation's sake, using inside-out thinking. In other words, they create products that are new, hip, and cool or have new, never-before-seen features. But these feature-laden products and services aren't developed in response to buyer-defined needs. While it is possible that a product or service created by a tuned out, innovation-driven company will catch on, it is much less likely than if the innovation were specifically designed to solve market problems. As a result, these innovation-led companies invest big resources in hopes of a big win (much like a baseball player swinging for a home run on each pitch). Their risk of failure is huge.

Only when an innovation solves people's problems does it become a potent force.

We realize we're being a bit radical here. But consider the piles of money plowed into innovation during the dot-com boom.

Venture capital firms funded innovative e-commerce companies, innovative Web tool developers, and innovative portal sites that sounded new, hip, and, well . . . innovative. Anything with an "e" in front of it qualified. But unless they solved an underlying problem, most of these exciting innovations have become distant memories. Remember: the truly successful Web companies, such as eBay, Yahoo, and Amazon, solved market problems.

We've also noticed that many innovation-driven companies obsess over competitors' moves and try to make incremental (and innovative!) improvements to what the other guys are doing. This approach assumes that your competitors are already connected to the things your market values most and that the game is just a simple matter of establishing a clear area of superiority (through innovation, of course). Another problem with this approach is that you tend to create products and services that are "better" than the other guy's because they are bigger, smaller, faster, or cheaper. Too often, your customers just don't care. Focusing on your competitors is a tit-for-tat game that rarely produces a market leader.

However, there's an important distinction to be made here. It is possible for a tuned in organization to learn about an unresolved market problem connected to another company's product. For example, buyer interviews might reveal that people are ready to pay money for a product that they describe in terms of the competitor's product ("a good-quality haircut in half the time that I would need to spend at the hairdresser in town"). Creating a product to solve this problem is definitely an example of tuned in behavior, even though the market problem is expressed as a comparison with an existing product.

But, in the end, a corporate personality built around innovation by itself has a low probability of success. Obsessing over the competition's product, or over your own product's increased performance or new features, means you aren't focused on the most important success driver: the market problems faced by your buyers. And, believe us, there is no such thing as the creative dreamer, sitting in an isolated office, who builds products that succeed every time. The dreams may sometimes hit a chord, but the vast majority of products made by innovation-driven companies just don't resonate with the market.

A second culture and strategy we see often is founded on the belief that revenue and sales are always the most important goals. This culture often emerges soon after an initial round of fund-raising or some other infusion of capital. When companies enter a perceived growth phase (dictated by the strength of a market opportunity or some early wins), it is common for outsiders (such as investors, the board of directors, or your spouse) to insist on a strong sales focus. In larger organizations, a highly charged sales executive is often hired; some companies even make the new salesperson the president and/or COO.

"Getting serious about sales" sometimes results in an initial brief period of success resulting from sheer force of will to push solutions into the market. But because the revenue-driven company will often lower its prices and cut corners as it hunts business—signing any contract to make the numbers and telling any story to close the sale—it's not long before the organization becomes tuned out to the real market problems of buyers. Then the salespeople start making promises that the company can't afford to keep. Non–revenue-generating departments (such as marketing, customer service, and product development) often suffer from reduced influence and resources. The company may even end up acquiring other companies and products to support the dynamic requests of sales, often resulting in duplicate offerings and lengthy integration programs that drive up costs without improving growth or customer satisfaction.

The revenue-driven organization worries about individual sales opportunities one at a time, rather than what resonates with a large marketplace.

In many consumer products the "Revenue Cures All" approach results in jumping on the hype cycle. Some organizations spend huge amounts of money on expensive advertising in attempts to buy their way into buyers' minds. These tuned out organizations believe that TV commercials, direct mail, and other forms of interruption-based marketing are the tools they need to succeed. Instead of spending time understanding buyers and their problems, hype-driven companies spend time with their agencies working on campaigns to bombard people with slogans and messages. We're not against advertising when used as a strategy to communicate powerful ideas that already resonate with people. The "Where's the Beef " campaign from Wendy's worked because it communicated an answer to buyers' problems.[12] (Hamburgers had beef patties that were too small.) But the hype-driven company manufactures buzz that has very little to do with helping people solve problems.

There are thousands of books, countless blogs and forums, hundreds of conferences, and lots of plain old common sense that suggest an unrelenting focus on the customer is the best way to guide an organization. But there is a fundamental flaw with being a customer-driven organization: Your existing customers represent a small percentage of your opportunity, they have different market problems than noncustomers (buyers who don't yet do business with you), and—most importantly—they only frame their view of your future based on incremental improvements to their past experiences.

For example, if a company in the late 1990s that made and sold portable music devices asked their existing customers what they wanted, they might say "more storage" or a "smaller unit." The companies that listened to their customers all missed the biggest market problems that were identified by Apple when they developed the iPod: the existing portable devices were too difficult to use and impractical for downloading and managing more than a few songs.

Because the customer-driven organization relies on existing customer requests for endless extensions to existing product lines, the company can't develop breakthrough products and services that resonate with noncustomers.

Don't misunderstand us—we're all in favor of great customer service. We just don't believe that an obsession focused solely on your existing customers is the right way to design and build product experiences and to reach the total market. Eventually, the customer-driven company gets bogged down by taking baby steps to tweak features in existing offerings (to please existing customers) rather than making the bold leap to develop new products and services that solve potential buyers' problems.

Assuming that your customer knows best is a comfortable strategy, because it's very easy to get feedback about how to conduct your business. "What do you want us to create next?" you ask. The customer is delighted to tell you. But you have listened to only a few people (those you already do business with) rather than many (the untapped market). Unfortunately, working only for your existing customers usually results in sleepy, increasingly unprofitable companies.

Ultimately, a focus solely on any of these approaches—being a customer-, revenue-, or innovation-driven company—is more risky. It is possible to build success, but the odds are stacked against you. And if you do beat the odds and develop a winner, you may still fail later. It might take years for the results of being tuned out to become apparent if your initially successful product can be turned into a cash cow.

Resonators are in the market, not in your mind.

We often see tuned out companies create products and services that do not resonate. To compensate, they must adopt drastic strategies to drum up business for their offerings. You know how many companies talk about their "product evangelists"? And how many organizations say that they are "missionaries in the market" and that they need to "educate people about the issues so that they see the value of our product or service"? These missionary selling strategies are simply symptoms of a tuned out company. You shouldn't have to wave your arms around and shout at people to convince them to pay attention to your product or service.

A resonator is a product or service that sells itself.

The tuned in, market-driven company understands market problems and builds products that resonate; these practices drive both sales and customer satisfaction.

If your organizational culture is closest to one of the three that we've outlined above, it means your organization is tuned out. The key distinction is that being tuned out requires that you guess when making important decisions such as what product to build, who to try to sell it to, where to sell it, and so on. But each time you guess at one of these elements, you introduce more risk into your business.

Consider your own organization. How would you answer these questions?

Do you build products based on what company insiders feel is best?

Do you use advertising campaigns to "create the need" in the market?

Do the salespeople dictate what goes into new products?

Do you watch the competition and make moves to follow them?

Do you only sell (and improve upon) whatever products you already have on the shelf?

Is the founder's (or CEO's) opinion the most important?

Are major decisions based on financial data alone?

Is gaining market share your primary objective?

You probably realize that a "yes" answer to any of these questions means you've got some of the symptoms of being tuned out and that you're guessing at what your market requires.

So why are people tuned out? Why are they guessing? If we look closely enough, we find a rather simple explanation. While it's not difficult to understand how to get tuned in, actually implementing the Tuned In Process is outside of many people's comfort zone.

While it's not difficult to understand how to get tuned in and transform your business, it's just easier to tune out.

We often lament what we've termed the "gravitational force" that tends to pull companies back to a normal state of being tuned out. Think about your organization's internal meetings for a moment. When you and your colleagues are in a conference room talking about how to create a product, market it, communicate with your buyers about it, or launch it into the market, how often do you make decisions based on mere guesswork? How often do you rely on experience and gut feel instead of the information you've collected from buyers who have a problem that your product or service solves? How often do you assume that the competition knows something important that you don't and that you should just copy them willy-nilly? How often do you participate in internal meetings to discuss "strategy" or "positioning" or "messaging," and then the entire discussion is based on the opinions of the people in the room and not the facts? How often does the person with the loudest voice in your conference room (or the executive with the biggest title) win an argument? Or consider this: how often are your organization's internal problems (to get a product to market, reduce costs, or impress the board and shareholders) more urgent to you than your buyers' problems?

A colleague of ours was recently helping plan a retreat for a university group. During a typical steering committee meeting, the group decided that an on-campus site was best because (they thought) there would be a bigger perceived time commitment involved in traveling to an off-campus retreat site. One night over dinner, our colleague mentioned the idea to a few new members (the "buyers" that the university group hopes will stick around and become active members) before finalizing the plans. It turns out that he and the rest of the committee were wrong—the new members actually wanted the event held off campus. Why? Because they're all freshmen who live in the dorms and don't have cars, so they wanted a chance to get off campus and see more of the surrounding area. Our colleague admitted that he and the committee were thinking, at least inpart, about their own problems, not those of their buyers.

"Your opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant."

We've got a simple saying that we use again and again when meetings and discussions fall victim to the inevitable gravitational force that draws groups away from the Tuned In Process that we know works: your opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant. We use the phrase to emphasize these ideas in our seminars and speeches, and we use it when we meet with one another. At tuned in companies, the boss's opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant; the founder's opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant; the salesperson's opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant. Most importantly, your opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant. What matters is your buyers' opinions. What market problems can your company solve with its products and services? Have you interviewed buyers, and do you understand their problems in detail?

We've participated in countless internal meetings that devolve into the usual tuned out nonsense—wild speculation about what new product or service might get the company out of the third-place position in the market or what slick advertising campaign will juice the sales results enough to appease the stockholders. These sessions always end in a guessing game about market needs; none of the opinions are ever grounded in hard data obtained by speaking to buyers about their problems.

But we've also been in meetings where one person, perhaps a product manager or marketing manager (or in the case of a much smaller organization, maybe it's the entrepreneurial owner's spouse), says something like this: "Well I've interviewed twenty potential customers, and here's what I've learned . . ."

Holy cow!

The room goes silent. Everybody leans forward. The BS artists clam up. Somebody has data! We can stop guessing!

We know that staying tuned in is difficult, particularly at first. You try your best to make decisions based on the market, but it's hard to do so consistently. The gravitational force pulls you back to relying on your own opinion in much the same way that poor eating and exercise habits creep back into the lifestyle of many people who are working to stay fit and healthy. We're certain that every company, even those we consider role models for the Tuned In Process, have slipped into relying on gut feel and instinct from time to time. Hey, we've done it too! As we were meeting to discuss marketing and promotional decisions for this book—things like potential book titles, and the best way to get the book into the marketplace—we fell into the behavior we advise others to avoid. One of us would passionately argue some point (a favorite subtitle perhaps) by using the words, "I think . . . " Then the other two would respond, mercilessly, with "Your opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant."

Organizations that develop products without first understanding market problems and buyer personas introduce a significant element of risk to their businesses. Sure, in some cases you can come up with a breakthrough all on your own and create some level of market success. It is possible. But, it's more likely that you'll miss the key to success that lies dormant in the mind of your buyer. Why reduce your potential?

In 2000, LG Electronics introduced the world's first Internet-enabled refrigerator.[13] While many new refrigerator-freezers at the time sported water and ice cube dispensers in the door, the Internet Refrigerator offered a few more features. "Based on 'Internet digital DIOS' technology," a press release announced, "the LG appliance is not merely a refrigerator with a built-in notebook, it unites a 'white goods' technology with an animated video telecommunications technology usually used for multimedia products, for the first time in the world." Other features of what LG called the "space-age" appliance included:

TFT-LCD (thin-film transistor, liquid crystal display) screen with TV functionality and Local Area Network (LAN) port

Electronic pen, data memo, video messaging, and schedule management functions

Information about the refrigerator and its contents, such as inside temperature, the freshness of stored foods, nutrition information, and recipes

A Webcam that doubled as a scanner, to scan food in and out and keep up with exactly what inventory was in the refrigerator and how long it had been there

Programmable interface to automatically send out orders, provided that the nearby grocery shops were online

MP3 player for music storage and playback

Three-level automatic icemaker for ice cubes, crushed ice, or cold water

We asked a simple question: What problem was the Internet Refrigerator supposed to solve? Lack of space in the kitchen area, maybe (because you don't have room for both a fridge and a computer)? Well it seems to us that if you can afford an $8,000 Internet Refrigerator, you can probably afford a bigger kitchen. And we doubt it's a good solution to the space problem anyway. Imagine your kids watching TV on the fridge while you're preparing dinner.

Maybe the unit reduces the time you spend on household chores? Well, do you really want to set up a complete supply chain– management system for the items in your refrigerator, complete with RFID-enabled groceries that allow this Superfridge to detect your grocery needs, log on to safeway.com, and then automatically arrange delivery to your house? Would this save time? Is this really a practical solution to your problems?

No, of course not. The Internet Refrigerator is a classic case of guessing—of tuned out, inside-out behavior. The Internet Refrigerator is also a classic case of innovation for innovation's sake and a great example of a product development failure. When organizations are not tuned in, the products and services they create just don't resonate. But it can be much worse. Often the tuned out company so annoys potential customers that they just go away.

As you get comfortable with the Tuned In Process, you'll soon begin to spot resonators. And you'll also find many examples of products and services, as well as the related company experiences, that just don't resonate. It becomes a bit of a game to spot tuned out behavior:

Make them groan when they open it: Opening a product shipped with packing "peanuts" is a miserable experience. First you have to dig your hands in and fish around to get all the items out of the box. Then you spend days picking up strays because the damn things fly all over the place. (Plus, they are terrible for the environment.) Companies that ship with packing peanuts do so for their own convenience; they're tuned out to their customers.

Lock up your label: Artists whose music was distributed on CDs by Sony BMG Music Entertainment in 2005 faced boycotts of their label when it was learned that digital rights management software was installed from CDs onto users' computers. The software even contained code that had the potential to cripple computers.[14] Message boards lit up with fans' frustrations. Attorneys general in many states, including New York and Texas, sued Sony BMG in class actions on behalf of consumers. Sony, while perfectly within its rights to protect ownership rights to the music it distributed, went too far and alienated consumers because the company was not tuned in to the buyers of their music and what was important to them.

Make them walk a mile to get to you: When customers arrive at shopping malls in the morning, they often find the lots already filled with hundreds of cars crowded around the entrances. "Why?" the customers wonder. "The stores aren't even open yet." It turns out that many shopping malls allow employees of their stores and restaurants to park in the choice spots. How easy would it be for mall operators to create a policy that encourages store employees to tune in to their potential customers' problem of finding a decent place to park?

Force them to do it your way: For at least the past five years (basically as long as we can remember), when we go to our ATM machine we always get $200 in cash. This is the procedure we endure: first swipe the bank card, enter a PIN number, and select "Get Cash" (because the amount of money we require is not in the "Fast Cash" selection). Then we are confronted with the same options each time—we can select $20, $40, $60, $80, or $100. Since our desired amount is not there, we press "Another Amount" and then manually enter our request for $200. Why can't the ATM machine remember that each time we want cash, we ask for $200? How difficult would it be to offer that as a selection? Is the company that made the ATM machine tuned out to the buyer persona that withdraws more than $100 at a time? Or is it the bank? Or both?

Make them work to find you: Many organizations insist on using antiquated letters for their phone numbers, years after some phone manufacturers stopped putting letters on keypads. Worse, they often fail to include numerals next to the letters when written, so it takes people quite a long time to work out what the phone number for, say, 1–555-TUNED-OUT actually is. While we're all for memory devices that make it easy for people to recall a phone number, the problem with this approach is the frustration many people have with translating the letters to numbers. Another frustration is that some companies use unusual spellings of company names and other words in the "phone number," making it difficult to figure out what number to call. (Some companies even exploit this confusion. Over $300,000 worth of the calls intended for AT&T's 1–800-OPERATOR number actually went to rival MCI's 1– 800-OPERATER).[15] These practices make it less likely that many people will actually place the call.

Scare them away from your events: The Washington, DC Metrorail stops running at midnight on weekdays, even on evenings when there is a late football game, concert, or other event in town. Thus, fans cannot use public transportation and so bring more cars downtown, leading to parking problems. For a city, like most, that is looking for ways to keep people in town after work (to support the local business community), is there ever a reason to stop a critical service like public transportation?

We laugh about some of these examples, but then we ask a serious question: how do business leaders let these things happen? The common failing here is cultural. All of these examples illustrate practices that make things easier for the company rather than the customer. We can only conclude that either these companies don't care or they got caught guessing.

The best predictor of business success is a focus on the Tuned In Process—an outside-in, market-driven approach. But we recognize that it isn't always easy to be tuned in. There's that gravitational force that wants to suck you back to being tuned out. Thus, we've devised a simple exercise to help you remind yourself to stay tuned in.

Your business must be continuously problem solving for your market.

Question: what business are you in? You'd probably answer by saying you're in the accounting business, or the shoe business, or the enterprise software business. And you'd be wrong. If you are a tuned in organization, you should answer, "We're in the business of continuous problem solving for our market." It's remarkable how that simple thought—the way you describe your business—helps to transform your mind and keep you tuned in.

Once we accept that definition for our business, it becomes evident that to survive we must understand the problems our prospective clients' experience. These problems are what should drive companies. In the next chapter, we'll introduce the Tuned In Process. Subsequent chapters will then go into much greater detail on each step of the process, providing examples of tuned in organizations that are creating their own success.

Of all the causes of tuned out behavior, the most common we've observed is the logical (but incorrect) assumption that, because you're an expert in a market or industry, you therefore know more than your buyers about how your product can solve their problems.

Most companies have a single dominant focus that drives their approach to business, a "company personality" that determines how each structures itself and behaves in the market.

The most successful organizations are tuned in, operating from a market-driven approach.

Debunking the myth of the innovation-driven organization: when these companies chase innovation for its own sake, they neither satisfy customers nor drive unit sales growth.

Debunking the myth of the sales-driven organization: these companies can juice sales for a while, but the added investment in more and more sales resources means that profitability and customer satisfaction often suffer.

Debunking the myth of the customer-driven organization: these companies limit their market to just the people who already do business with them, and so end up failing to grow.

A focus on any of these approaches—being a customer-, revenue-, or innovation-driven company—is more risky. It is possible to build success, but the odds are stacked against you.

Our research shows that tuned in organizations are in the distinct minority.

There is a "gravitational force" that tends to pull companies back to being tuned out, as if that were their normal state. Staying tuned in is difficult, much like staying on an exercise program. This is not a natural way for people to think and behave (at least at first).

We've got a simple saying that we use again and again when meetings and discussions fall victim to the inevitable gravitational force that draws groups away from the Tuned In Process: Your opinion, although interesting, is irrelevant.

The old tuned out way of operating is just easier. But organizations that develop products without first understanding market problems and buyer personas introduce a significant element of risk to their businesses.

Your business must be a continuous problem solver for your market.