For probably as long as there have been tickets for sporting, concert, theater, and other live events, people have found themselves with extras they cannot use. And there have been countless other people prepared to pay for good seats when those are no longer available or even when the event is completely sold out. Until recently, the only option for buyers and sellers was to venture into the dark and murky world of ticket scalpers, who show up at popular events to hawk tickets. Seats for premier concerts like The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, and Hannah Montana, as well as National Football League and Major League Baseball games and international sporting events like the Olympic Games or World Cup soccer matches, often sell out quickly, leaving fans who wait until the last minute with nowhere else to turn. At the same time, those with extra tickets know that they have something of value but don't often have a convenient outlet for connecting with buyers.

StubHub identified this market problem in 2000 and quickly created the largest ticket marketplace (by sales) in the world. StubHub offers fans an online marketplace to buy and sell tickets at fair market value. The problem of having or needing extra tickets is one that many fans have experienced, and it's quantifiable because the face value is right there on the ticket—if you've got two extra tickets to the Roger Waters concert and you paid a hundred bucks each for them, you've got a $200 unresolved problem and you're willing to act on it. It's also possible to quantify the extent of the problem for the person who is ready to buy tickets, because she has a price in mind that she's willing to pay to score those hard-to-find seats to a sold-out show.

Interestingly, StubHub also identified another kind of ticket aftermarket for shows that are not sold out—sellers who are willing to take a loss on their tickets just to get even a little cash back, and buyers who are thrilled to purchase seats for less than the box office price.

Understanding these distinct but complementary problems (sellers of tickets and buyers of tickets are two distinct buyer personas), the StubHub online ticket marketplace created a breakthrough experience for fans, providing an easy way to buy or sell tickets in a safe, central, and reliable online environment. StubHub also partners directly with sports teams to help their fans get rid of extra tickets, thus alleviating some of the stigma of scalping, which has been illegal in some locations (although most U.S. states have relaxed such laws due to an overwhelming outcry by citizens). In August 2007, Major League Baseball and StubHub established a five-year deal for StubHub to become the official online provider of secondary tickets for MLB.com, the official Web site of Major League Baseball. As a part of the deal, StubHub also received official, club-endorsed status from each participating Major League Baseball team.[28]

By getting tuned in to the unresolved problems of tickets buyers and sellers, and quantifying the impact on consumers (as we'll teach you how to do in this chapter), StubHub created a breakthrough experience that resonated. As a result, the company has enjoyed tremendous success. In early 2007, StubHub was acquired by eBay in a deal worth $310 million. And in October 2007, the company announced that it was quickly approaching its ten millionth ticket sale since its founding in late 2000. Considering it was less than a year earlier—November 2006—that StubHub hit its five millionth ticket milestone (with a sale of tickets for game two of the 2006 Major League Baseball World Series), this growth rate is amazing. This is the power of a resonator in the hands of a tuned in organization that understands the quantifiablesizeofitsmarket.

There are three important criteria for you to consider as you measure the potential market for your product: (1) Is the problem urgent? (2) Is it pervasive in the market? (3) Are buyers willing to pay to have this problem solved? (And you also want to know how much the willing buyers are ready to pay, of course.) Quantifying this information is a critical and often overlooked step that you should perform before developing any products or services. Having the discipline to answer these questions will keep you from having to guess about whether a product can become a success.

Before you create a product or service, you must know that the problem you will solve is urgent and pervasive, and that buyers will be willing to spend money to solve it.

You need to run your ideas for a product or service through what we call the "urgent," "pervasive," and "willing-to-pay" filters. The answer to all three questions must be "yes" before you begin to create a product or service. If you encounter any negative answers, you should consider dropping the idea and move on to something else.

When you identify problems in the market, make sure that people really care about them. Are they actually urgent? We recognize that "urgent" is a powerful word and that you might doubt the need for this filter. But nothing is more frustrating than working yourself silly to solve a problem that either doesn't exist yet or that people describe as "not a big deal."

The ticket resale market that StubHub identified fits the "urgent filter." We've been on both the sell side and the buy side of the ticket resale market, and can confirm that when you want to see a show (or have a few hundred bucks worth of tickets you don't need), the problem becomes urgent (just ask any Stones diehard or parent of a Hannah Montana fan). If the event is in a few days, you've got to act; StubHub can help.

You should identify a problem shared by a large enough number of people; otherwise it's not worthwhile for your organization to develop a product or service to solve it. Thus, it's important to use quantitative measurement to verify the commonality of the problem. How many people have this problem? Are there any unifying characteristics of the people who have the problem?

The ticket resale market that StubHub identified also fits the "pervasive filter." Every day there are countless sporting, music, theater, and other live events in thousands of cities and towns where people have extra tickets and others want to buy them.

Identify a problem that people are willing to pull money out of their pocket (or their companies' bank accounts) to solve. Tread carefully on this point, because most people have all kinds of problems that they're just not willing to pay money to solve. For example, you may hate going to the grocery store, but are you willing to pay someone else to purchase groceries for you? Apparently not that many people are, because many grocery delivery services have appeared in recent years and struggled to find enough buyers willing to pay for the service.

The ticket resale market that StubHub identified fits this third filter too. Sellers of tickets are happy to pay a small commission to StubHub in order to recoup some of the ticket price. At the same time, buyers are prepared to pay a premium to attend a sold-out show. And those looking to buy tickets to an event that has not sold out are willing to offer something less than face value, saving money from the price at the box office even after the commission.

Until now, the Tuned In Process we've shared with you has been qualitative—that is, we've described how to conduct research on market problems and interview buyer personas by getting out of your comfortable offices and actually talking to people. However, once you find a compelling problem that your organization can solve for buyers, you must switch to measuring and quantifying the potential buyer impact of your problem or service. This will help you determine if solving this problem for buyers is worth your company's effort. Quantifying the impact is the step that will help you build a business case for your new solution.

However, it's critical that you not simply skip to this step. We see many companies that short-circuit the process by creating an insideout product (dreaming it up in a conference room instead of by going out and understanding buyer problems) and then apply measurement tools to validate the already tuned out idea. Don't fall into this trap!

The people behind StubHub discovered market problems first. That made the measurement step easy, because tickets have a well-defined face value. If you purchased a pair of tickets and cannot use them, you know exactly how much you'll lose unless you can sell them. Similarly, when people want to attend a sold-out show, the price of a coveted ticket typically starts at face value and goes up from there. It is also possible to quantify how many events occur in certain cities and how many typically sell out.

At this stage of the Tuned In Process, you can start to use measurement tools such as surveys. But remember, we never recommend using surveys to find unresolved problems. Remember the remote locator? If Magnavox had asked: "What problems does your TV have?" Very few people would have said: "I lose my remote." People often cannot identify problems for themselves. So to find unresolved problems like Magnavox did, you should always perform that step through in-person interviews.

There are a number of ways to measure the impact of solving a problem.

Publicly available (and free) sources such as data from the U.S. Census or industry and trade associations.

Specialist research reports that can be purchased "off the shelf" for a few hundred to several thousand dollars.

Surveys that you conduct yourself or commission from a survey firm. These surveys can be conducted via telephone, in person, or by mail.

Web-based surveys. If you have your own online contact list or a well-trafficked Web site, you may get people to respond to your request for information.

Telemarketers may be a good resource. Using a telemarketing firm or your own people to measure is not sales. Instead, you call a bunch of people to see how many have the problem you've identified and then ask if they would pay to solve it.

As we discussed in Chapter 2, many companies just guess when deciding what products and services to introduce to the market. But the Tuned In Process is a terrific way to stop the guesswork that goes on in so many organizations. We've witnessed the transformation that takes place when companies start to use the Tuned In Process, and many executives are amazed at the result.

Absent any real data, conference rooms are just full of opinions.

We love the hush that transfigures a conference room when an employee provides quantitative data showing how urgent and pervasive a newly identified problem is, and how much money people are willing to pay to solve it. That hush is usually followed by an excitement, since those present understand that the product development team can now jump right in and start developing a creative solution, using the company's distinctive competence. (We will elaborate on this process in Chapter 7.) If someone else in the conference room has a different idea, the group simply asks to see market data to support it. If there's no data, it's just an opinion, and is therefore irrelevant. We realize that this sounds harsh, and we also know it's not how most companies do it.

Data trumps opinion every time.

Let's be realistic. Even though we advocate getting product ideas solely from buyers, we know there are times when an idea comes instead from the company founder, the CEO, someone in the product development department, a customer, or even—in certain circumstances—a competitor. And we know many employees sometimes feel an insurmountable pressure (or even a direct mandate) to proceed with such ideas against all common sense. (Remember the Susan B. Anthony dollar from Chapter 2?) The Tuned In Process's solution to this common occurrence is what we call an Acid Test. When you are being pressured to build an inside-out product, we suggest that you simply let the market decide whether it's a good idea. The Acid Test doesn't take long to prepare and need not be expensive.

First, you need some kind of prototype to show to buyers. It doesn't even need to be a completed product or service; you could just prepare a presentation (one like your salespeople would give) and use that to show what your organization plans to offer. Next, meet with potential buyers one at a time (not in a focus group situation). Don't tell them the benefits of your product or service—just show them what it does and ask them the following questions:

What problems does it solve?

How would they benefit from using it?

What impact would it have on them, their families, or their companies?

Finally, you will plot where your new product or service idea fits on a spectrum we call the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum. For example, some people think getting the daily newspaper is a valuable part of their day. For others, newspaper subscriptions are no more than another daily chore: walking to the street to pick up the paper, later on tossing it into the waste can, usually unopened.

On the far left of the continuum are products and services that have very little or no impact on your buyers' lives or jobs. On the far right, we plot products and services that represent a breakthrough. These products have a real and meaningful impact on buyers—like a medical advance that could save your life. Of course, most products lie somewhere in between, so you'll want to speak to a large enough sampling of buyers to accurately place your new product or service idea on the continuum.

This is not to say that low impact is always bad and high impact is necessarily good. Low-impact products—such as rubber bands—can be profitable. But you see lots of headlines about life-saving medical breakthroughs, not about the humdrum rubber band industry. Low-impact products, often considered commodities, march along quietly in a relatively stable market.

All that matters is your prospective customers' perceptions of the impact of your product on their lives, relationships, or jobs.

Doing an Acid Test and plotting the results on the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum allow your organization to be realistic about a product or service's potential for success. The Acid Test helps you identify low-impact products before you invest heavily under the mistaken assumption that your product will be important to buyers. Because it doesn't matter what you think about the product or how much you have invested—all that matters is what your buyers think. On the other hand, high-impact products carry a significant risk because they are typically expensive and time-consuming to build. That is why an Acid Test is essential before the investment is made. If it is a bad product idea, the earlier you kill it, the better.

When you visit prospective buyers to perform the Acid Test on your as yet undeveloped product, draw the continuum on paper or a white board, and ask them to place on the chart some products and services that they already use. For example, if you sell a software product, ask them if they own Microsoft Word. If they say yes, ask them to point to where it fits on the Impact Continuum. Once they indicate the spot, your next question should be "Why did you choose that location?" Their answers will provide valuable information about what problems the product solves for this buyer.

Help them with one or two more products, and then ask them to name some products (that they already own) that are low impact and some that are high impact. At this stage, your buyers are likely to be enjoying this "game" and are happily plotting other products on the Impact Continuum. In each case, ask them why they placed each product where they did. Then, after you show them your prototype or sample, ask them where they would place it on the Impact Continuum. Many companies we've worked with have been shocked by what they find out. The "killer product" that you were sure everyone would love and value somehow winds up off to the left, exiled in low-impact territory by your buyers. On the other hand, we have seen very simple products—even ones that companies have given away for free—score very high on the Impact Continuum scale.

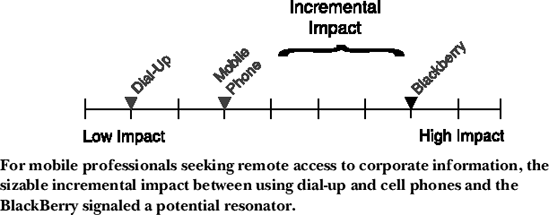

Research In Motion (RIM), the company behind the BlackBerry handheld communications device, identified a common problem: professionals who are frequently on the road couldn't keep up with e-mail and data from the home office. Internet technology had evolved to enable on-the-road connectivity, but unless you were in a hotel room that offered dial-up access, you had no way to stay connected to your valuable information. And dial-up service, the only option at the time, was painfully slow.

Initial buyer personas for the BlackBerry were professionals such as salespeople, individual consultants and financial services specialists (who might buy a unit to become more productive), and their department heads (who might buy a bunch of units for everyone on the team). Businesspeople who spend days or weeks away from the office need to know what's going on before meetings. Did anyone send me an important e-mail? Is there anything in the news? Did someone in the home office update important data? A mobile professional needs to answer all these questions, and if he or she can access the information immediately before meetings, they can stay in the data loop.

The problem RIM identified passed the urgent, pervasive, and willing-to-pay money filters. A businessperson is only as good as the information they deliver, so keeping up with the latest is certainly urgent. Millions of mobile professionals work in North America, so the problem is pervasive. And although the BlackBerry wasn't cheap upon launch (several hundred dollars to buy the unit, and a monthly fee to subscribe to the wireless data transmission service), many high-income individuals and team leaders were willing to pay to solve their communications problem with a BlackBerry.

The product was a tremendous success and continues to grow. As of April 2007, Blackberry service network had 8 million subscribers and Research in Motion has sold 6.4 million units in the current fiscal year.[28]

We've plotted the results of the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum for RIM as they were investigating market problems that eventually led to the Blackberry.

The results of your Acid Test can help you with more than just making a decision about whether to move ahead with a product. One clever use of this process is that, once the potential customer has plotted a number of products (including yours!), you can go back and research the prices of the other products and get an indication of how you should price your new offering.

We know of one business-to-business software product that provided network administrators in large organizations with a seamless way of interfacing multiple operating environments. The utility took less than a day to build and cost nothing to replicate. The company's product development insiders wanted to give the product away, since it had only taken one day to develop. However, the product scored as very high impact with buyers on the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum scale. So the marketing people, armed with data from the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum scale, priced the product at $20,000. All the opinions of company insiders were proven wrong when the company began selling many copies of the software.

The Acid Test and the Impact Continuum identified a product that insiders wanted to give away but that instead became a highly profitable resonator.

In another example, a colleague had planned to charge $12,000 for a business product, but buyers rated it much higher on the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum scale, so they changed the selling price to $72,000. In another case, a product everyone inside the company thought would be a clear winner scored very low on the Tuned-In Impact-Continuum scale, so it was never produced, probably saving the company a great deal of money and resources.

When you conduct your Acid Test, remember that representatives of diverse buyer personas will rate the same product and service in dramatically different ways. The more you solicit input from potential buyers, the better your data. For example, bank presidents might rate the Wall Street Journal as high-impact, but truck drivers typically don't. By asking both groups why, you learn what problems the product solves for buyers who rate it as high-impact. You can then communicate to other potential buyers in the same market segment that you have solved those high-impact problems.

Even products that were created using the Tuned In Process should be run through the Acid Test. Although you will already know that the problems you're trying to solve are urgent, pervasive, and worth spending money on, an Acid Test helps you confirm that you actually solved the entire problem. The worst scenario for a tuned in product is that you provided only a partial solution to the problem you identified. Obviously, most buyers don't want a partial solution, so they'll be unlikely to buy it. More importantly, though, by going to market with a compelling but only partially solved problem, you open the door for more agile competitors to come in with the complete solution.

Congratulations! If you've read this far, we thank you for sticking with us. If you're beginning to apply the Tuned In Process to your own business, now is the time that you create a brief written proposal to help you articulate your idea for a product or service to your constituents.

The proposal is the tool you'll use to succinctly articulate your product or service. You can use the proposal with internal audiences such as the product development team, your spouse, and salespeople. And it can also be used as a tool to help communicate your ideas to potential investors, business partners, and others with a stake in your idea.

We suggest that a simple one- or two-page business proposal, one that encapsulates the essence of the product or service you want to create, is all you need. Your short proposal should include the details of what you've learned so far in the Tuned In Process: your targets and strategy, the operating details, and how you will make money from the product or service. It doesn't have to be any more complicated than that.

Your proposal should answer the following questions:

What detailed unresolved problems are you solving?

Who will your solution impact (what buyer personas) and how many such people are there?

What product or service will you create to solve the problem?

How does your product or service impact buyers?

How will buyers quantify that value?

What will it take to convert prospects into customers?

A tuned in business proposal will help you make "go/no-go" and "buy versus build" decisions.

While we recognize that there are countless other details that can (and often do!) go into these documents, answering the questions above in as simple and straightforward a way as possible will help your decision makers determine a course of action. Above all, remember that your most important task is capturing the essence of how you (or your business) are going solve problems in the marketplace.

Measurements of business success (or lack of it) are a tricky matter for many companies. Among the leaders we've interviewed in the past ten years, the ones who were successful made sure to measure only what was important to run their businesses; they avoided or ignored the distracting data that often flood executives. Tuned in organizations don't fall prey to the typical requests for minutia that come from investors, boards, and analysts. Their leaders recognize the disease that leads to death by metrics. Of course, nobody would argue that data and metrics have no value, particularly when these numbers provide transparency into company performance.

The problem with measurement is that too many companies have trained their employees to measure the wrong things.

Many managers are required to deliver detailed metrics on such things as the number and type of sales leads (sometimes on a daily basis), the number of "PR hits" (magazine and newspaper articles mentioning the company), the number of visitors to each of the company's Web pages, engineering productivity rates, regional sales performance, and this, and that, and more. Well, guess what? Those numbers don't matter. They only serve to create an environment where people work hard but not smart. Measuring the wrong things (such as Web hits, press clips, and the like) leads to tuned out behavior.

Instead, you should measure how many meetings with buyers you and your team are conducting. How often do you get out of the office and meet with actual people to learn about their problems? Measure the impact of solving the problems you've identified. Measure how your different buyer personas learn about new ways to solve their problems. And, once your product or service is out on the market, you should measure how well it resonates with each of your buyer personas.

In short, when creating a tuned in product experience, recognize that you should only measure what matters. Measurement will serve as the dashboard for how you run the organization and will help to answer questions: Should you spend money to create a new product or service? Should you expand your marketing programs to reach a new buyer persona? Should you develop a new channel to reach the European market?

Tuned in leaders keep track of the meaningful information they need to drive the business forward, not a bunch of trumped-up data used to justify employees' tuned out work.

According to Forrester Research, one-third of Web users refuse to use credit cards online, a huge issue for people who sell goods and services or solicit money over the Internet.[29] Gary Marino knew about this problem with doing business online because he had worked as chief credit officer at Citibank for fifteen years and ran credit and marketing operations at First USA. Thus, he founded a new company, Bill Me Later, to solve this market problem. His company learned that people were concerned that their personal credit card information would be stolen. Although the industry reports that less than 1 percent of credit card fraud is associated with interception of credit card numbers through online shopping, buyers perceived it as a real problem. Bill Me Later also learned that, oftentimes, a customer might not have access to the credit card number at the time of the transaction (for instance, if his or her wallet wasn't nearby). And a large market segment chose not to carry a card at all, despite having good credit scores.

In 2002, Bill Me Later set out to introduce a new credit vehicle for consumers—a daunting challenge given that many big banks (such as Marino's former employers) had tried to and largely failed. The last resonator developed by the industry had been the Discover Card, launched at great expense over twenty years earlier.

To use the Bill Me Later payment service, online consumers simply enter their birth date and the last four digits of their social security number. Bill Me Later can then, through their patented process, instantly approve the credit account. The company then follows up two weeks later by mail with a bill for the purchase. The consumer then has the choice of paying it off interest free or making payments over time, just like a credit card. This process solves serious problems for those who don't carry a card and those who are concerned about Internet security. At the same time, online merchants who made Bill Me Later one of their payment options generated more sales.

In fact, Bill Me Later conducted buyer persona research with the merchants to learn about their market problems too. They discovered merchants were paying 2 percent or more in fees to credit card companies, so Bill Me Later offered their service for 1.5 percent, knowing that every percentage point was important to margin-conscious online retailers. Another problem these merchants faced was high abandonment rates for virtual shopping carts (people sometimes shop online, put stuff in their "baskets," and then mysteriously go away). The new Bill Me Later payment option dramatically reduced the abandonment rate, and merchants even said that Bill Me Later clients were shopping more often and spending as much as 250 percent more than comparable credit card customers.

Bill Me Later became a resonator for both merchants and online shoppers. The company has signed up hundreds of merchants, including Wal-Mart, PETCO, Overstock.com, Continental Airlines, SkyMall, JetBlue, Hotels.com, and 49 of the other 200 top online retailers.

And because of initial success, the company garnered $100 million in venture capital funding. As of 2007, after only five years, Bill Me Later had rocketed to number six on the Inc. 5000, Inc. magazine's list of the fastest-growing privately held companies in America. They reported growing from $613,000 in revenue in 2003 to $53.6 million in 2006 with transaction volume in excess of $1 billion—with only 100 employees.

By getting tuned in to customer problems, merchant problems, and even investor problems, and then quantifying their impact, Bill Me Later was able to create the perfect solution for each party. We hope that by studying the stories throughout this book, you've also learned how to create a resonator of your own.

Once you find a compelling problem that your organization can solve, you must switch to measuring and quantifying the impact on buyers.

Measurement will help you determine if solving this problem for buyers is worth the effort for your company.

There are three important criteria for you to consider as you measure: (1) Is the problem urgent? (2) Is it pervasive in the market? (3) Are buyers willing to pay to have this problem solved?

Quantifying the impact of the problem will provide the data you need to build a business case.

A simple one- or two-page tuned in business proposal encapsulates the essence of the product or service that you want to build and will help you make "go/no-go" and "buy versus build" decisions.

Measurement will serve as the dashboard for how you run the organization—that is, how you go about the business of solving your customers' problems. Thus, you should only measure what matters and not get bogged down by meaningless corporate data like Web site hits and productivity rates.