12

We are not just telling a story — we are telling it to an. audience. It is therefore necessary to determine how the audience reacts to the manner in which the story is told. For the time being we shall confine ourselves to the effects of the dramatic construction upon the mind of the spectator, leaving the examination of the effects of the actual story content to the third part of the book.

The reactions of the audience are neither unpredictable nor uncertain. The public reacts to certain parts of the story in a certain manner. Knowing this, the writer is in a position to obtain the desired reactions from the audience at his choosing.

Only the novice writer believes that the reactions and moods of the actors in his story will cause identical reactions and moods in the audience. If the characters in the picture laugh and are amused, it does not necessarily mean that people in the audience will laugh and have a good time. As a matter of fact, some of the most successful comedians greatly amuse their audience without laughing once themselves. Jack Benny evoked peals of laughter by his silences. For instance, in one skit, when Mr. Benny’s held up at gunpoint, the robber asks: “Your money, or your life?” Instead of answering, Mr. Benny remains mute and stone-faced while he considers the terrible alternatives.

Likewise, sadness of the actors on the screen does not necessarily make people in the audience sad. Nor will the spectator be fascinated just because the actor is terribly interested in what he is doing. Excitement, gunplay, and much movement on the screen do not necessarily excite the audience. The spectators may watch these happenings in complete boredom. On the other hand, silence may put the audience into a state of excitement. The laughter of an actor may make the audience cry, and the sadness of a character on the screen may make them laugh.

The experienced writer knows that the reactions of the audience are not identical with those of the actors. Nevertheless, the reactions of the spectators are not independent: they are caused unavoidably by certain elements in the story.

Moreover, it must be understood that the quality of the story content does not necessarily create interest or suspense. A story with superb qualities may be supremely dull, and a very trite and common story may be intensely interesting.

A correct dramatic construction presents the story content in the most effective manner. It should prevent the spectator from feeling boredom, fatigue, dissatisfaction, and lack of forward movement. It should cause surprise, hope, fear, and suspense.

We must learn so to construct a story that it will arouse, sustain, and steadily increase the interest of the spectator. To achieve this, we must make use of the spectator’s capacity and ability to anticipate.

Concerning what can be called reverse gladness or reverse sadness, i.e., an audience experiencing one or the other when the author’s intention is just the opposite: Joseph Kesselring’s play Arsenic and Old Lace — about two seemingly harmless old ladies who poison gentlemen callers — was written as serious melodrama, but its first audiences laughed at it. Play doctors advised the producers to simply play it as all-out comedy, and as such it became a big hit. The Epstein brothers then scripted it into a hit film directed by Frank Capra (made in 1941, released in 1944).

Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994) pays homage to the all-time Hollywood master of reverse gladness and sadness, of laughter and tears.

Writer beware! Don’t make audiences laugh where they ought to cry, or vice versa.

Anticipation

Anticipation is the ability of the spectator to foresee a happening which is to take place in the future.

In order to enable him to anticipate an event which is to take place at a future moment, he must know of something that is intended or planned to happen. For instance, a stone breaks loose from a housetop. The spectator anticipates that it will hit the ground. Or a man intends to go to New York. The audience anticipates that he will reach New York. However, if nothing is intended or planned by persons or objects in the story, nothing can be anticipated.

Notice that we said intended or planned by persons or objects in the story. In no event should the spectator anticipate the intentions of the author of the story. Such false anticipation has done much to discredit anticipation as a valuable reaction. Stories which “telegraph their ending,” to use the technical term for false anticipation, are indeed devoid of merit.

But true anticipation, which is caused by the intentions of actors in the story, is of great value to the construction of the motion picture. William Archer in his book Playmaking states: “The essential and abiding pleasure of the theatre lies in foreknowledge. In relation to the characters of the drama, the audience are as gods looking before and after. Sitting in the theatre, we taste for a moment the glory of omniscience. With vision unsealed, we watch the gropings of purblind mortals after happiness and smile at their stumblings, their blunders, their futile quests, their misplaced exultations, their groundless’panics.”

The nature of anticipation is not easily recognized. Although the intention is the preliminary condition for the spectator’s anticipation, it does not conclusively determine this anticipation. The spectator’s anticipation is a reaction which is merely set into motion by the intentions appearing in the story.

This is due to the fact that an intention is not certain to attain its goal. And it is up to the spectator to decide whether to believe in the fulfillment or frustration of the intention, choosing, so to speak, what outcome he wants to foresee.

In many cases, where the goal — that is, the result in the future — follows with certainty upon the intention, our anticipation will be certain. For instance, the sun “intends” to rise every morning. We anticipate that it will rise every morning. But then again, we may state, “The water will begin to boil — if it is long enough on the fire.” The second part of the sentence expresses the uncertainty of our anticipation. Perhaps somebody will extinguish the fire or take the pot away. Then there are intentions which have no chance to succeed, because they are hopeless or impossible. In this case the spectator will refuse to anticipate their success, even though the actor in the story believes in it. If an actor in the story proclaims that he is going to jump to the moon, the spectator will by no means anticipate seeing him there but, deciding for himself, expect to find him in an insane asylum.

This being the case, we need knowledge to decide what the probable outcome of a happening is going to be. And this knowledge is a result of our experience.

Experience, in turn, is proof accumulated through repetition. If the same thing behaves in the same way under the same circumstances, it is logical that it will continue to behave identically. If this repetition is constant enough to take place a hundred thousand times, it can be crystallized into a scientific law of absolute exactitude, thereby guiding our anticipation with certainty.

We expect the sun to rise every morning as it has for many thousands of years. But in the dark past of mankind even this anticipation was uncertain: in pagan times, men still feared that the sun might fail to rise one day, leaving the earth in eternal darkness. After a few thousand years of experience, man is fairly certain that nothing can go wrong with his anticipation of the sunrise. This made it possible for the prophets to base some of their most horrifying predictions upon the contradiction of such certain anticipations: “The sun will stay still in the mid-heaven.” The prophets who directed their prophecies to simple people knew that the movement of the sun was a well-established anticipation which — if it was broken — would cause the realization of a terrifying change in nature.

Thus we understand that several spectators may have different knowledge with regard to the same happening so that they may anticipate differently, some correctly, some wrongly, and some not at all.

In real life, every person anticipates in many instances a reaction which has become so automatic that he may not even be aware of it. A man who drops a letter in the mailbox anticipates that the post office will deliver the letter to its destination. A secretary who rushes to catch the bus anticipates that the bus will leave the street comer at a certain time.

Our anticipation can be provoked by customary happenings, by legal institutions, by the constancy of psychological patterns, or by mere repetition. But with regard to human behavior, a fact which is repeated four or five times will already induce us to anticipate its recurrence.

For instance, if a person has been established as honest, we anticipate honest actions from him; we refuse to believe that he would commit any dishonest deeds. If we see how a man is beaten, we anticipate that he will react, because he know that we would react, and we know that other people would react when they were beaten. We anticipate further that his reaction will be to defend himself and not to treat the aggressor to an ice cream soda. If someone steals money, he must anticipate being put in jail soon after he is caught.

The general knowledge of the spectator, which varies in comprehensiveness, can and must be enlarged by information given in the story with regard to a specific person or happening. For instance, you must let the audience know that a father is brutal in order to make them anticipate that he will beat his child who has broken a window.

The information, supplied by the story, will cause us to anticipate as long as it contains the element of repetition. We may remember that the very definition of a characteristic is based on repetition in contrast to the passing mood. Therefore the factor of repetition, whether in regard to a character or event, may be merely stated or implied; it can, however, automatically arise should the same happening be shown three or four times in the course of the story.

If a swindler marries women as a method of obtaining their money, we anticipate after the second or third woman that he will act similarly with any other woman he meets.

Repetition is a very frequent effect in comedy: every time a comedian appears, he asks a certain question. After the third or fourth time, the audience anticipates that he will ask the question. If it was funny, they will laugh before he has even opened his mouth. It is a comedic reiteration of the old Pavlovian dog experiment.

Now it is clear that information given by the story may be replaced or even contradicted by later information, during the progress of events. Consequently, our anticipations are subject to constant changes, being interrupted, transformed, or replaced. For instance, in Neil Simon’s The Out-of-Towners (1970), directed by Arthur Hiller, Jack Lemmon plays a young executive flying to New York for an important business meeting. Everything has been prearranged, but nothing goes according to schedule. His plane is detoured to Boston, he misses a train connection, he loses his reservation at the Waldorf Astoria, he is held up and arrested, and on his way home he is hijacked to Cuba.

However, in each instance, an anticipation which is not led to fulfillment must be interrupted and thereby destroyed. The anticipation which is left dangling in the air causes a subconscious dissatisfaction on the part of the spectator.

All of us have experienced the feeling which is created when somebody promises to telephone and fails to do so. The disappointment may not be warranted by the importance of the call, but is simply a result of our dissatisfied anticipation.

Thus it is not practicable to show a train heading toward a broken bridge and in the next scene to show the travelers at their destination. It is not feasible for an actor to intend to steal cattle and then fail to do it without telling the spectator of this change in plans. So long as this change is not made public, the spectator will anticipate that the man will steal cattle. The longer it takes, the more impatient the spectator gets. And if the picture ends without the man having stolen cattle, the anticipation of the spectator is definitely dissatisfied. The following brief explanation on his part might have destroyed this anticipation: “I am going to become an honest man.”

There is a familiar joke based upon dissatisfied anticipation. A salesman who is sleeping in a small inn is awakened in the middle of the night by another guest who returns to his room on the upper floor badly intoxicated. With utter disregard for the sleepers, the drunk throws one of his boots to the floor. One hour passes. Finally, the salesman can bear it no longer. He knocks at the wall and shouts: “For God’s sake, throw that second boot down, so that I can go back to sleep.” Many pictures are full of second boots which fail to fall.

It must be realized that not only the spectator anticipates; the actors on the screen are also in a position to anticipate. The general anticipations, based on universal knowledge, are the same for all human beings: the actor as well as the spectator anticipates that a burning match in the haystack will start a fire. As for other anticipations which are based on specific knowledge, the actor may possess information which is different from that of another actor or from that of the spectator. This was explained in the chapter on division of knowledge. We merely have to add that the anticipations of two actors in respect to the same thing may stand in complete contrast. Or the anticipation of an actor may stand in contrast to that of the audience, which has different information.

This contrast in anticipation is most effective. For instance, a man who is H.I.V. positive makes plans for a new business. He does not know that he has A.I.D.S., whereas the spectator is so informed. A criminal intends to start an honest life, unaware that his old pals are waiting to kill him. A couple enact a love scene on board the Titanic. Their anticipation: a happy honeymoon; the spectator’s anticipation: the shipwreck. Or a comic effect frequently used in early movies: somebody carries a pack, not conscious of the fact that it contains dynamite. With complete confidence he lights a match and smokes a cigarette, anticipating that nothing will happen while the spectator anticipates that the dynamite will explode.

The unanticipated event. Nothing is more dramatic. No one expected the great ship Titanic to sink, or the Hindenburg dirigible to explode. And both events inevitably inspired motion pictures: Titanic (1953; 1997), and The Hindenburg (1975).

In modern times one of the writer’s greatest challenges is to script what is unanticipated with a believability approximating the all-seeing eye of live television: the explosion of a spaceship with teacher Christie McCauliffe on board; the Rodney King beating; O.J. Simpson’s Bronco chase.

Since an event which is planned for the future can move into the present, a relation exists between the anticipated event and its actual execution.

We anticipate a certain happening. The event occurs just as it was anticipated. That is: fulfilled expectancy.

We anticipate a certain happening. Another event takes place instead. That is: surprise.

Fulfilled expectancy is not necessarily a disadvantage. There will be numerous cases in a story where an anticipated event will take place as it was foreseen. For instance, a man intends to kiss a woman. We anticipate that he will kiss her. He actually does. Or a gangster intends to break a safe. He does.

The danger of fulfilled expectancy is that it is almost a duplication: we are showing the spectator something which he already knows because he foresaw it. Therefore the anticipated event must be shown quickly, if it is shown in fulfillment, or the event must be so thoroughly interesting that the audience will not be bored. In many instances it is interesting to compare the anticipated event with the one which the imagination foresaw.

Surprise is one of the most important effects of any story, whether it is used for comedy or drama or tragedy. Surprise can only be achieved by way of anticipation. We must anticipate that another event will take place in order to be surprised by the actual outcome. If we do not anticipate anything, we cannot possibly be surprised. In this sense, it must be recognized that a perfectly peaceful state of affairs, where absolutely nothing is anticipated, contains a definite anticipation, namely, that nothing will happen. If then suddenly something does happen, our anticipation is surprised.

Such being the case, the spectator must be led to believe in something before he can be surprised. For instance, a clown starts to jump over a fence. He begins with considerable preparations, making it absolutely clear that he is going to jump. He indicates the great difficulties of this feat, thereby intensifying the anticipation of the spectator. Again and again, he indicates his intention, until the audience anticipates his jumping with absolute certainty. Finally, he walks around the fence. The anticipation of the audience is surprised. The audience is fooled and will laugh. For decades clowns have made people laugh by such simple deception of anticipation. We may also remember the comedian who repeats a funny remark upon each entrance. After three or four times, the anticipation of the audience has become so strong that they will start to laugh upon his entrance. After their anticipation is strong enough, the comedian can surprise them by saying something else, thereby arousing a new wave of laughter.

The same holds true for the drama. For instance, a man has been established as a law-abiding citizen. The audience has been led to believe firmly in his honesty. Suddenly it is shown that he is a criminal. It is obvious that the audience could not be surprised if it had no opinion of the man. Only because the spectator believed in something else could he be surprised.

For example, in the several film versions of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde we first meet Dr. Jekyll as a law-abiding citizen, and then his alter-ego as a psychopathic killer who is, in effect, the dark side of the same person.

Charlie Chaplin made frequent use of surprise to cause laughter. In one of his pictures he jumps from a bridge into the water. We anticipate that he plunges into a river. But the river turns out to be a shallow puddle, so that he falls flat on his stomach. In The Gold Rush (1925) a woman comes smiling toward him. He anticipates that she smiles at him and is very happy. But the woman passes by and goes to a man who stands behind him. In The Great Dictator (1940) he prepares to fire an enormous cannon. Again and again, we see the colossal cannon and all his preparations. We anticipate a tremendous explosion and a projectile which will go twenty or thirty miles. Instead, the projectile comes out slowly and falls down at a short distance.

Another effect of anticipation is the delay. Delay is only possible if we anticipate an event at a certain time. Let us assume that a murderer intends to kill a woman. We know that the hero is to arrive at her house at a certain time. But time passes by and he does not arrive. This delay is extremely effective. If we did not anticipate his arrival, at a certain time, we could not be irritated and excited by the delay. For example, a door opens, and we anticipate that somebody will enter right away; instead, a long time passes before the person enters.

As long as we anticipate a certain event at a certain time, the event may take place too early instead of too late. For instance, a woman thinks that her husband will be absent for a week; instead, he returns after two days and surprises her with another man. Her surprise results from her anticipation that he would return at a later date, while the husband’s surprise results from his anticipation that he would find her alone.

Last, it must be recognized that the anticipated event may be pleasant or unpleasant for the spectator. If the anticipated event is pleasant, the spectator will be eager to see it executed. You may have overheard remarks in small movie houses after the hero of the picture has declared his intention to beat the living hell out of his adversary. Your neighbor may have nudged you and said, “Boy, this is going to be good.” Your neighbor’s enthusiasm is caused by the anticipation of the beating the villain is going to get. He can hardly wait until the motion picture narration gets to this scene. If the hero had failed to make public his goal, your neighbor would have continued chewing his gum in complete boredom, being unable to anticipate something pleasant.

But the anticipation of something unpleasant fills us with fear. For instance, a child has broken a window at home. The father has been characterized as a brutal person. We fear a frightful beating for the child.

A hopeful anticipation as well as a fearful anticipation can be surprised. The promised beating which the hero was going to administer to the villain can turn out to be a beating for the hero. Our anticipation is surprised. The surprise of a hopeful anticipation can only be disappointment. In the example of the fearful anticipation, the brutal father may forgive the child. Again we have surprise. The surprise of a fearful anticipation can only be relief.

In a story with intention and counterintention, the spectator will experience contrasting anticipations: the anticipation of the deeds of the hero, and the anticipation of the deeds of the villain. The first may represent a pleasant and the second an unpleasant anticipation. Consequently, the spectator may experience hope and fear at the very same moment. For instance, the villain is about to torture the hero’s girl. We anticipate his deeds and are full of fear. But we also know that the hero is on his way to the house where the villain holds the girl. We anticipate his arrival. We are full of hope, while at the same time we are full of fear. The entire scene before the hero’s arrival stands in the shadow of our anticipation of his arrival. The moment he comes in we experience relief, because our fearful anticipation is surprised or destroyed. However, we do not feel surprised because the hero arrived, since we anticipated it. If he were to come too late, our hopeful anticipation would be surprised or disappointed. In order to make either effect possible, we must inform the audience that the hero is on his way to the house.

Thus the screenwriter must arrange the story information in such manner as to cause anticipation if he wants to obtain the valuable effects of expectancy and surprise, fear and hope, disappointment and relief.

Suspense

Suspense is a scarecrow for most moviemakers. If there is anything wrong with a picture, it usually is attributed to lack of suspense. If a picture lacks construction, if the story is dull and the line confused, the usual advice is: add some suspense. Great hopes are based on suspense, as if this word contained some magic medicine, as if it had all by itself sufficient power to help us overcome all deficiencies of a narration. Yet few people seem to know exactly the characteristics of suspense and how to achieve this effect.

Despite its importance, suspense is only a secondary effect deriving from other dramatic elements. Suspense becomes possible only with a strong and correct structure. It can never exist by itself, it cannot be added, and it can hardly be corrected or improved by itself, because it depends too much upon the other elements.

Suspense is not an element of the story, but a reaction of the spectator to the story. If it is said that a story has no suspense — it is meant that the spectator is unable to feel suspense when the story is told to him.

Suspense is the doubt of the spectator as to the outcome of an intention of an actor in the story.

Therefore the first necessity in order to achieve suspense is the intention. A story without intentions cannot possibly cause any suspense.

The intention sets a goal. In the absence of any difficulties, there is no doubt that the intention will attain the goal. Because there is no doubt, there is no suspense for us. The story will move quietly toward a goal which has been set by the intention.

In order to create a doubt, the intention must hit against difficulties. In the resulting struggle between intention and difficulties lies the doubt as to whether the intention will be frustrated or fulfilled, and whether the goal will be attained or not. And as long as the spectator doubts the outcome of the intention, he experiences suspense.

It seems as if this were fairly easy to understand. But it is amazing how many different ways are tried to achieve suspense. There is, however, no other way of achieving it than the one described.

One of the frequent mistakes results from the fact that a story without difficulties for its intentions moves quietly toward the goal. Obviously, the spectator cannot experience any suspense. From this, people conclude that the lack of suspense is a result of the clearness of the goal. They think that the spectator does not experience suspense because he knows exactly where the story is heading. They attempt to repair this absence of suspense by withholding the goal. In doing this, they do not create suspense but confusion, because suspense is not blindness but uncertainty.

Lessing in his Hamburg Dramaturgy states, “By means of secrecy, a poet achieves a short effect, but in what enduring disquietude could he have maintained us if he had made no secret about it. Whoever is struck down in a moment, I can only pity for a moment. But how if I expect the blow, how if I see the storm brewing about his head?”

The spectator must know where the story is heading, but he must be uncertain whether the goal will be attained or not. And in order to create this uncertainty or doubt, the spectator must know of difficulties standing in the way of these intentions.

Very often, suspense is confused with curiosity. This confusion is understandable — if not pardonable — because the reaction of the spectator is similar. In both cases he asks the same question, What is going to happen? Curiosity, however, results from our lack of knowledge of what the actor wants, while suspense results from our lack of knowledge as to whether the actor’s intention will be fulfilled or frustrated. The resulting reaction from our side is similar but the causes for it are different.

Curiosity is our desire to find the goal, while suspense can only exist if we know the goal. Therefore the two are opposed to each other; both cannot exist at the same time. The exposing of the goal which destroys curiosity is the preliminary step for suspense, and the absence of the goal which is necessary for curiosity makes suspense impossible.

Curiosity can be a very good preliminary to suspense. If we are first led to ask, What is the goal? we are more interested in the goal than if we were told right away. After the answer to this question is given, that is, after the goal has been exposed, suspense begins to work if there are difficulties in the way of attaining the goal. Curiosity in relation to the main goal can only exist in the beginning, while suspense can continue throughout the narration. But before each auxiliary goal we can have the transition from curiosity to suspense, if we desire it.

It is easy to make the difference clear by way of an example: A terrorist puts a time bomb in his bag. We know that he wants to blow up something. But we do not know what. We are curious. Later we learn that he wants to blow up a ship. Now we know the goal, but we do not know as yet whether he will attain his goal. We experience suspense: will his intention to blow up the ship be fulfilled or frustrated?

Because the definition of suspense means simply that it is the doubt as to the outcome of an intention, suspense can be achieved in thousands of different ways. For instance, a fugitive is hiding in a barn. A peasant enters the bam. Will the fugitive’s intention to hide be fulfilled or frustrated? Or a man wants to catch a train. He is held up by traffic. Will his intention to catch the train be fulfilled or frustrated? Or a jockey intends to participate in an important race. He is locked up in a room by the villains. Will his intention be fulfilled or frustrated? Or a villain is about to commit a crime. Will the hero arrive in time to prevent the fulfillment of the villain’s intention?

Suspense is not necessarily bound to blood and murder. A tender love story can have suspense as long as it adheres to the same principles of intention and opposing difficulty, thereby creating a doubt in the mind of the spectator.

Thus intention and difficulty are equally essential in creating a doubt in the spectator. Primarily, it does not matter how strong and powerful each of them is. But it does matter what the balance of strength between them appears to be. For if the strength of the intention appears to be much greater than that of the difficulty, its chances for success and victory are uncontested. Consequently, there can be no doubt as to the outcome. Furthermore, if the strength of the difficulty seems to be considerably greater than the one of the intention, its chances for success are obvious. We cannot doubt that the intention will be frustrated.

In order to achieve a doubt, and thereby suspense, the chances for the success of the intention or of the difficulty must be nearly equal.

Let us assume that you are on an ocean liner. The ocean liner has powerful machines, great resistance against storm and waves; it has instruments of navigation and a trained crew. Its chances for success, that is, crossing the ocean, are far better than are the chances of the ocean — as the difficulty — to resist. We have intention and difficulty, but the chances for success are not equal; therefore we cannot experience suspense. If, however, the ocean liner is torpedoed and the people get into the lifeboats, the chances of success are about equal. The chances of the difficulty lie in the vastness of the ocean, in storm and waves, in the lack of drinking water and so on. The chances of the intention lie in the fact that the survivors may be picked up by passing boats or that the wind will drift them to an island. The equal chances make it possible for us to experience suspense.

Likewise, this applies to an airplane flying from Los Angeles to Honolulu. The chances for the airplane to reach its goal are much better than those of the difficulty to prevent it. This was proven in dozens of previous flights. But let us assume the pilot suddenly discovers that the fuel tank is leaking. Will the fuel last until they reach land? It is the leakage which makes suspense possible, because now the chances for fulfillment and frustration are nearly equal.

Let us assume that you go to a prizefight between the heavyweight champion and an unknown boxer. You will not be able to experience suspense, because you cannot doubt that the champion will win. But if he fights against a well-known and indomitable opponent, the stadium will be full and the crowd will be tense and excited, because the chances for both fighters are about equal. In both cases, the champion may put up an equally vigorous fight, but in the first instance we are not able to experience suspense, and in the second we can.

Translated into story terms, it means the following: two men who want to kill each other offer good suspense, because you have intention and counterintention, or intention and difficulty. If you characterize these two men as strong and ruthless, you have better suspense. A courageous, but resourceless man who wants to kill a coward who is very powerful offers excellent suspense.

Although this seems very obvious in a clear analysis, mistakes of that sort often happen, mostly because of the writer’s enthusiasm to make his hero wonderful, and the opponent a combination of all bad and despicable qualities. The latter vilification is permissible as long as the opponent is powerful, and his badness is not identical with weakness. If his despicable qualities are represented as ruthlessness and villainy, and at the same time are combined with power, then suspense is achieved, because the chances of success are about equal. Alfred Hitchcock expressed it like this: “I always respect my villain, build him into a redoubtable character that will make my hero or thesis more admirable in deflating him.”

It was said that the strength of the difficulties which are faced expose the strength of the intention. Simultaneously, they expose the chances for the success of the intention. For instance, an army of five thousand men defends a town. It is not likely that an opposing force of two hundred men will attack the five thousand men, because the chances of success are too unequal.

It is possible that a cop will single-handedly burst into a nest of gangsters, though it appears as if the odds were all against him. But by the simple fact that he dares to brave such odds, we assume that he must have some reason for doing it; that is, he must have some other chances for success which are as yet unknown to us.

The realization that such situations contain very powerful suspense has led some writers into grave mistakes. They allow the hero to face an obviously desperate situation. Afterwards, he is not saved by some assistance which he was anticipating — a fact which would correspond to the law of the equal chances of fulfillment or frustration — but by some accidental help. This is downright silly. A hero who goes to a place where he knows a dozen criminals are hidden is not a hero but an idiot. If the hero is then saved by the accidental arrival of police, he was not worth saving, and the writer insults the intelligence of the audience.

The spectator weighs the chances subconsciously. But motion pictures have spoiled the natural feeling for weighing the chances to a large extent, because they made a practice of letting everything come out well at the end. We were so used to the hero’s victory that we did not give up hope, even though things seemed to be absolutely hopeless. We still felt suspense, even though there seemed to be no possible doubt that the hero’s intention would be frustrated. This is false suspense, however, because it is based upon hope and confidence in the kindness of a producer who would not disappoint us by letting things come out in a bad way. The following example will serve to illustrate the difference between true and false suspense: A train carrying the hero and the heroine heads toward a bridge which has been destroyed. The train travels at a speed of seventy miles an hour and there is no warning. Consequently, we should not feel any suspense, because there is little doubt that the train will plunge into the river. But because we like the hero and the heroine, we shall not give up hope that something will prevent the train’s intention to fall into the river. This is false suspense. However, if a guard who discovered the fallen bridge, runs as fast as he can toward the train in order to warn the engineer, then we have true suspense. Will the guard warn the engineer in time? Will the train’s intention be fulfilled or frustrated? Obviously, true suspense is much more exciting and powerful, and we should search the script carefully for equal or unequal chances. It is very simple, at times, to insert a reason to make the chances equal, as was shown in the above example.

The reasons determining the chances of fulfillment or frustration of an intention may exist whether the spectator knows about them or not. But we must realize that the spectator cannot experience suspense until he is informed of the difficulties opposing the intention, as we have seen in the example of the train and the guard. From this we derive the demand that the information be given at the opportune moment in order to obtain the best values of suspense.

Let us consider this example: The villain has lured the girl into his home and intends to kill her. We cannot doubt that he will fulfill his intention, for he is stronger than the girl. However, the hero is on his way to the villain’s house. If he arrives in time, he may be able to save the girl. Now let us consider when the information about the hero’s intention should be given? If we are not informed about this intention, the hero’s intention exists nevertheless, but the spectator is not capable of experiencing suspense. All of the villain’s preparations for the murder are without suspense. When the hero arrives, his arrival is unexpected and not effective for the spectator. Instead, the information about the hero’s intention to go to the house should be given at about the same time that the villain’s intention to kill the girl is exposed.

During the progress of the story, the chances for fulfillment or frustration may change and, with them, our doubt. If the difficulty is an obstacle, it may be overcome gradually by the intention. Our doubt or our suspense is subject to very rapid changes. This is desirable because it makes the outcome unpredictable. The victory of one side over the other may either happen gradually or rapidly. Rapid change in the chances for fulfillment or frustration is identical with Aristotle’s conception of the reversal: After the chances for both have been equal for a long time or even favorable to one side, suddenly one or the other gains decisive superiority. We say decisive superiority, because there must be one point where the doubt about victory or defeat of the intention must be replaced by certainty. And this decision is the climax.

If suspense is the questioning about the outcome of intentions, the climax gives the answer. After the climax there is no more doubt possible about whether the intention will be frustrated or fulfilled. An answer dissolves a question. The climax destroys suspense. It is therefore clear that the climax should be as near the end of the picture as possible in order to make use of suspense up to the very end. The climax is not identical with the end of the story. It simply represents the decision as to victory or elimination of the difficulty. The progress of the story from climax to attainment of goal is without interest because it lacks suspense. We can even go as far as to imply the actual attainment of the goal, because there is no doubt left that it will be reached. This is the case in many love stories. After all the difficulties have been eliminated, we need not show the lovers married.

This completes our investigation of the nature of suspense.

The Forward Movement

Moviemakers are very much concerned with the forward movement of a picture. They will exclaim enthusiastically that it moves at a rapid pace or they may sigh in dejection that it is slow. This may be the case with the entire picture, or only with certain parts. “It drags in spots.” Thereupon, the slow spots are cut shorter and shorter, until hardly anything is left, which makes other parts of the picture difficult to understand. The mystery of the slow or fast forward movement of the picture can seldom be solved by cutting.

Of course, it is not the picture which moves fast or slowly, because the picture is driven forward by the electric motor of the projection machine at a steady speed. It is the mind of the spectator which must be moved forward from the beginning of the story to its end.

The mind and the imagination of the spectator are fundamentally inert. They sit down with the spectator in the seat of the theatre. They have no forward movement of their own. But they have the faculty for certain reactions. By arranging the story elements in the right order the writer is able to attract the mind of the spectator to move forward. If the story fails to contain these elements, the verdict of the spectator is that the picture was slow, long, and boring.

The forward movement is something new — brought about by the form of motion pictures — and moviemakers have good reason to be concerned about it. The theatre is not so interested in the forward movement, because its time is uninterrupted. Each second of its scene or act represents a second of actual time. Therefore it cannot move faster or slower, and the movement of the mind of the theatre spectator is identical with the movement of the play, neither slower nor faster. The novel does not know this kind of forward movement, because the reader can put the book away at any time he likes and does not have to sit through from the beginning to the end. Furthermore, the novel has the connecting sentences which lead the reader smoothly forward, while the interruptions after each scene in the picture are felt very harshly. It must be realized that the lapse of time between scenes interrupts the smooth flowing of the forward movement. Each scene represents an even forward movement because the time in each scene is identical with actual time. But the lapse of time — being of different length — represents a very dangerous discontinuation of the forward movement.

We must understand that the form of the motion picture is not a continuous entity; instead, it is a conglomeration of blocks, represented by shots and scenes. These blocks have the tendency to fall apart, thereby interrupting the continuity of the story in a decisive manner. In order to overcome these breaks we must search for connecting elements within the story. If these elements of the story overlap the breaks caused by the technical subdivision, we can achieve connection. With this in mind, we understand the predominant importance of the forward movement in motion pictures compared to that in other forms of storytelling.

We must search for the elements in the story which cause our imagination to move forward. In order to find them, it is necessary that we understand the elements of dramatic construction very thoroughly. Only a moviemaker with very definite knowledge of the laws of dramatic construction is in a position to make a motion picture which “moves fast.”

If we were to compare our mind with that of a man who walks on a highway, we would undoubtedly believe that he knows where he is going. He must have a goal, otherwise he would not walk, but stand still or sit down. And this is exactly what the mind of the spectator does during his march along the story if he is not told what the goal is.

In order to cause any kind of forward movement a goal must be set. The setting of a goal is the preliminary condition for the forward movement. Without it, the spectator will not move, and the picture will be slow, and uninteresting.

As soon as the goal is set, the spectator anticipates the possibility of its attainment. This anticipation expresses itself as a desire to arrive at the goal. And this desire causes the forward movement in the mind of the spectator.

In general, our anticipation works so strongly that we want to attain the goal immediately and resent the actual execution of the intention before attaining the goal. The delay caused by necessary but time-absorbing actions appears as a hindrance of the forward movement.

In order to eliminate this impression of hindrance we have to insert doubt, that is, suspense, because then the attainment of the goal which is desired by our forward movement is not merely hindered by a delay but made altogether uncertain. Suspense is fundamentally an unpleasant feeling from which the spectator would like to escape. This sounds strange because we know that suspense is very desirable for the movie script.

Being an unpleasant feeling, suspense helps the forward movement. We would like to obtain certainty. It is often said that the certainty of something bad is preferable to uncertainty which leaves open the chance for the happy outcome. It is said that the certainty of the death of a relative is less tormenting than if he is missing. Therefore, in order to run away from the uncertainty which is felt as suspense, the spectator moves forward toward the goal and toward the decision which makes clear the outcome of the intention. As such, the forward movement of the mind of the spectator is a product of his anticipation and his suspense. For anticipation, we need a goal, which, as we remember, can only be set by an intention. And for suspense, we need a doubt as to the outcome of the intention, which, as we remember, can only be created by a difficulty.

It is our desire to create a smooth and fast forward movement of the mind of the spectator. Now that we know its causes, we can proceed to arrange the elements of the story in such a manner that we may obtain the best possible results.

We find that the main goal of the story should be set as early as possible in order to cause anticipation; this means that the intention setting the goal should start very near the beginning. At the exact moment at which the intention begins and the goal is set, the forward movement starts, because anticipation makes us desire the goal. Before the goal has been set or before the main intention has been exposed or caused, the story will slouch along at a slow and reluctant pace; it will only gather speed after the main goal is clear. Previous to that, we have no desire to get anywhere — we sit still.

As soon as the anticipation begins to work, we begin to resent all further actions as a hindrance if we do not experience any doubt as to whether the goal will be attained. Again we feel that the picture is slow.

In order to make our speed identical with that of the picture, we have to insert the doubt. The difficulty opposing the intention and making the attainment of the goal uncertain must be exposed soon after the intention has been set. If the time elapsing between the exposition of the two is too long, we have the disagreeable feeling of being hindered in our forward movement.

It was said that the climax dissolves our doubt or suspense. This being the case, we must take care that the climax is near the end of the picture, for after the climax, or after the destruction of suspense, we begin to experience the same feeling of hindrance if we cannot attain the goal shortly.

Lastly, it must be said that the main goal must coincide with the end of the picture. Our forward movement stops the moment the goal is attained. If the picture proceeds further, that is, if it moves forward after the goal has been attained, we are unable to follow. The rest of the picture — from the moment that the main goal is attained to the end — ambles along or dangles in the air.

In looking back, we already find four definite reasons for creating or hindering the forward movement. And furthermore, we see that the speed of the forward movement is subject to changes. It can be slow in the beginning, then take on speed, then become slow again, then gather speed, then lose it again, and stop completely before the end, according to the time when the main intention begins, when the difficulty appears, when the climax takes place, and then the main goal is attained as compared to the actual ending of the picture.

Now we are ready to find further determining factors for the forward movement. The main goal is attracting the mind of the spectator. But it must be realized that much of its strength of attraction is being lost in the distance. The further away we are from the main goal, the more its power of attraction is weakened. Obviously, we are further away in the beginning of the story. The more we proceed, the closer we come.

We could compare the main goal to a powerful magnet. In order to overcome the weakening of the power of attraction because of the distance, we can put up smaller magnets along the road which attract us forward. As soon as each one is reached, its magnetic power is extinguished; thereby our forward movement is continuous and gathers momentum toward the main goal.

These magnets along the road are represented by the auxiliary goals. Since they are goals, they can be anticipated by the spectator, and if they are anticipated, they cause a forward movement. If they are wisely arranged, they contribute greatly to our forward motion until the main goal becomes powerful enough to attract us by itself.

There is no fixed rule or ratio which would guide their distribution. They should be chosen in accordance with the necessities and requirements of each individual story. Each story contains innate auxiliary goals, and even though their distribution is irregular, it may be satisfactory and does not demand any correction. However, if there are large spaces without any auxiliary goal, our forward movement slows down. These large spaces without auxiliary goals are so-called slow spots or dull parts of the picture although much may be happening in these parts. But we are not led to anticipate anything — therefore we do not move forward. Frequently, the cutter is supposed to correct these deficiencies in the completed picture by cutting out sections from these dull spots. Yet this correction was the duty of the writer, who should have inserted or created auxiliary goals.

It is a fundamental principle that it is the anticipation of an auxiliary goal which causes the forward movement, and not the briskness of the dialogue or the swift action of a scene. Imagine, for instance, a scene in which a man visits a woman. He talks brilliantly, his dialogue is brief and precise, and the scene ends before any apparent dull moment could occur — yet the scene is without forward movement, as we do not anticipate any auxiliary goal. Imagine now that we know this man came to see the woman in order to kill her. He comes in and begins to talk about the weather. No matter how dull and slow the dialogue, no matter how many uninteresting things may be said, the scene will have an uncanny forward movement, because an attracting auxiliary goal exists. As a matter of fact, the hindrance caused by the slowness of the actions and dullness of the dialogue makes us all the more conscious of our forward movement. It makes us impatient and this impatience strengthens our will to get somewhere — it strengthens our forward movement.

Thus the experienced writer can exploit the attraction of a good auxiliary goal even further. The strong forward movement will help to alleviate the hindrances caused by much exposition and unavoidable information. Even the best writer cannot escape giving certain expositions which are less interesting than the rest of the story. But he may give them in this way: A person approaches a man in an attempt to learn something which is extremely interesting. The man, either through stupidity or ill will, talks about everything else, but not about that particular subject. “Everything else” the man talks about, is of course exposition and information which we would hardly want to listen to if it were not for our forward movement caused by the anticipated auxiliary goal. The writer has transformed a deficiency into an excellent dramatic effect. Not only does he give us the exposition, but in doing so he accentuates our anticipation by making us impatient. The auxiliary goal as a magnet draws us over the slow spots. Our forward movement is hindered by the difficulty which — in this case — only intensifies our will to arrive at the auxiliary goal. Let us consider for a moment how far we have already advanced: not only are we able to cause the forward movement, but we can even dare to hinder this forward movement, thereby gaining a new effect.

In order to obtain the smoothest forward movement, we must be aware of the following fact: the auxiliary goal has the capacity of attracting us until it is reached. But as soon as it is reached, it loses its attraction. The extinction of the attracting power of the auxiliary goal has a tendency to stop our forward movement. It has the tendency to let us slump down. As soon as one auxiliary goal is eliminated, the duty of moving forward the mind of the spectator rests upon the following auxiliary goal or goals, and of course upon the main goal. It is clear that this duty can only be transferred if the following auxiliary goal exists already and not if it must be set after the preceding goal was extinguished. In order to guarantee a smooth forward movement, the following auxiliary goal must be set somewhere in the middle of the previous intention. Then it takes over automatically where the first goal leaves off. But if the new auxiliary goal is set only after the preceding goal has been eliminated, our forward movement will result in jumps and halts and not in a continuous flow toward the conclusion of the story.

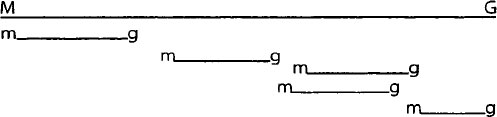

To make this appear more clearly, we can represent graphically the correct and the wrong appearance of the auxiliary goal. Let us assume that the entire picture is represented as a straight line. The main intention should begin with the beginning of the picture, and the main goal should be attained at the end. Underneath, we can show the subintentions as smaller lines, beginning with the motivation and ending with the auxiliary goal. Not only is it necessary to have a fairly even distribution of the auxiliary goals, but the beginning of the subintentions must overlap each other.

In the graphic description, we are able to distinguish clearly the connecting power of these overlapping subintentions. We must remember that the closer we come to the auxiliary goal, the stronger its power of attraction. After the one is eliminated, we approach the succeeding one, which in turn begins to attract us more and more. Now consider a representation of faulty connection:

It is apparent that after each auxiliary goal, we are left without attraction. Our forward movement stops. Then suddenly a new auxiliary goal is set, which makes us rush forward. After it is eliminated, we are let down again. Our progress is similar to that of an old automobile — a series of jerks and stalls and not the smooth forward movement of a modern engine.

It may seem that our conclusions are very abstract. However, after these factors are thoroughly understood, their application is fairly simple. It is not too difficult to recognize the essential subintentions in a story. After they have been recognized, it is a simple matter to find where they are revealed, that is, at what moment the spectator begins to anticipate an auxiliary goal.

Thereafter one recognizes at once whether there are large spaces of story time without subintentions, and therefore without forward movement, and whether the subintentions are overlapping one another or not.

It is necessary that we compare the capacity of the auxiliary goals and of the main goal in their relation to each other. First we must recognize that the goal may arouse the anticipation of something pleasant or of something unpleasant. And these two different types of anticipation affect the forward movement.

Let us again compare our mind with that of a man who walks on a highway toward a distant city which is his goal. The man may anticipate a wonderful dinner after he gets to the city, or he may anticipate a friend or a good night’s rest in a hotel or a profitable business deal. In all these cases his anticipation contains something pleasant. Obviously, the man is eager to get to the city and his forward movement is fast.

However, it may be that the man anticipates a jail sentence upon his arrival in the city or that he expects a beating from his enemies. We are safe to assume that he will refuse to move forward, unless he is compelled by some powerful reason.

These examples refer to the anticipation caused by a main goal. The anticipation of pleasant or unpleasant things with respect to the auxiliary goals affects the forward movement in a different way. If the main goal is to get to the distant city, and the main anticipation contains something pleasant, like the union of two lovers, the auxiliary goals can be unpleasant without disturbing the forward movement. Auxiliary goals are unpleasant if the man has to suffer cold and hunger, has to sleep in hard beds, and becomes tired from the strain of his journey. All this, however, will not make him stop, because the main anticipation is pleasant.

Translated into motion picture terms, we understand that the mind of the spectator will move forward more eagerly if he anticipates a happy ending. It will not move forward if it has to expect “a beating” upon arrival. The auxiliary goals may be unpleasant and terrorizing. But their terror will not disturb the forward movement, because they are only stepping stones on our way to attain something pleasant. As a matter of fact, this terror of the anticipated auxiliary goals may be anew cause for the accelerated forward movement: we want to get it over with in order to arrive at the pleasant main goal.

Let us again consider the example of the man on the highway: We notice that he is standing before a road sign. At the bottom of the sign he reads the name of the distant city — the main goal — in large letters. Above, in much smaller letters he finds the name of three or four towns which come before this main goal. The main goal is made clear by the size of its lettering.

Let us assume that a sailor who is easily persuaded comes ashore in San Diego. He wants to go to his home town, which is thirty miles beyond San Francisco. The auxiliary goal as represented by San Francisco is much more attractive and much more important than the main goal which is his home town. There is every reason to suspect that this particular sailor will remain in San Francisco and get drunk and never reach his home town. This can be very easily altered by reminding the sailor that his best girl, whom he has not seen in two years, is waiting for him in the home town. Immediately, all the attractions and seductions of San Francisco lose their power over him, and the big city becomes an unimportant station before the great goal of seeing his girl again.

We may be permitted to compare our imagination to a drunkard who has very little resistance against any kind of temptation. Our intelligence can be very adult and full of will power. But our imagination remains childlike. It is intrigued by the slightest sensation; it is aroused by the slightest temptation, and then it is very difficult to control. Should one of the auxiliary goals become more attractive or more interesting than the main goal, the imagination, like the drunken sailor, will only reluctantly move on. The result is that from this attractive auxiliary goal on, the journey to the end of the story becomes uninteresting because the forward movement is hopelessly reduced.

Frequently, the author fails to make clear which is his main intention and which his subintention. Then the spectator may falsely assume that a subintention is the main intention, believing that the end of the picture is reached when the auxiliary goal is attained. To his astonishment, the picture drags on until what the author believes to be the main goal has been reached.

The attraction of the main goal must be the most powerful of all. However, a comparatively unattractive auxiliary goal in the beginning will still be able to attract us because the powerful attraction of the main goal is so faraway. The closer we approach the main goal, the stronger the auxiliary goals must become in order to exert any kind of attraction.

This is the dramatic graduation of values. A casual love scene at the beginning of a picture may be very good. The same scene before a bullfight which may cost the life of the matador, would seem ridiculous. The love scene must become important, tragic, or poignant.

Thus every following event must be more attractive in order to move us forward, in order to make an impression upon us. This graduation must be applied to every part, to every element of the story. Every characterization must grow toward the end. Every emotion must be gradually strengthened. Every decision must become graver. Every event must become more interesting. This represents no small problem. If the writer fails to achieve thorough graduation of all the elements, he will be confronted with effects which he had not intended. Those parts which he fails to graduate will remain stagnant, losing interest and value because the others have progressed.

If well handled, the uneven graduation may become an effect. For instance, a battalion of soldiers passes, on its way to battle, a farmer who is tilling his soil. On the way back, the soldiers meet him again. In the meantime, they have gone through hell, they have fought, they have suffered, their friends have been killed, but the farmer is still there, working his soil as before.

Professor George Pierce Baker, in his Dramatic Technique, writes that it is the common aim of all dramatists to win as promptly as possible the attention of the audience. This unquestionably correct demand has often been misunderstood. It is true that the interest of the audience should be aroused immediately, but not by events which are so impressive as to prevent a subsequent graduation.

While it is desirable to begin with interesting events, impressive events should be saved for later on in order to obtain a steady graduation. It requires discipline, restraint, and wisdom to arrange the events in such manner as to obtain an even graduation. Many pictures achieve a terrific beginning — which is desired by most producers — but are unable to continue. They throw the spectator into forward movement with a jerk but are unable to keep up the speed. Most of these pictures are disappointing toward the end, for no other reason than the fact that the powerful beginning cannot be graduated. If the beginning were less impressive, the rest of the picture would become more interesting. In Hollywood one speaks of a school of first act writers. Their “first acts,” that is, the beginnings of their stories, are very powerful, but the rest is disappointing. At times this first act serves its purpose: it induces the producer to read a script, instead of discarding it after a few pages. But it does not serve the purpose of making good pictures for the audience. Such stories are top-heavy, and no effort of rewriting can balance them, because no graduation is possible.

Television has aggravated this danger by its demand that the viewer be “hooked” at the very first moment. Years ago, the filmmakers could count on a captive audience in the movie theaters, so that they developed their expositions at a more leisurely pace. But today, when a nervous switching to another channel may bring about the demise of a series in the rat(ing) race, the viewers have been conditioned to beginnings that pack a wallop. And the moviemakers, aware that their theatrical films will end up on television, have increasingly speeded up their openings, to the point of capturing audience interest before the main title.

A startling or dramatic opening does not necessarily preclude a subsequent crescendo of emotional and suspenseful clashes. The gimmick at the beginning, no matter how explosive the impact, does not yet affect the audience as strongly as a less forceful scene after we have become involved with the protagonists of the story.

Nevertheless, it becomes clear that we should only choose emotions and characterizations which will allow graduation. They must be planned in such manner as to make the gradual strengthening possible. Many a script, in a natural desire to graduate its intentions toward the end, permits them to outrange their motives and characterizations. The result is ridiculous: we may remember the example of the engineer who finds himself fighting for his life while all he wanted was five hundred dollars a week. The result of graduated intentions from weak motives is a giant on baby feet. It may also happen that the subintention is more powerful than the main intention, which again is ridiculous. In order to overcome such dangers, the writer should choose his characterizations and main motives for strength; then he has ample possibilities of strengthening the subintention toward the end without disrupting the proportion between the elements of the story.

The climax of this development comes when no further graduation is possible. This means that graduation should be distributed over such a space that its highest point coincides with the end of the picture. If this moment is reached earlier, the remainder of the picture becomes stagnant. If the picture ends at a time when we are still able to anticipate a further graduation of its elements, the end comes unexpectedly and unsatisfactorily.

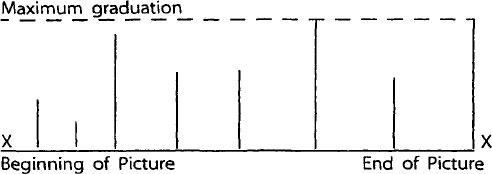

Graphically, the correct graduation would look like this:

Uneven graduation would look like this:

Incomplete graduation would look like this:

Graduation seems to require subtle sense of evaluation on the part of the spectator. In fact, it may appear that the realization of such values and the evaluation of the general strengthening of each element requires a sensibility which is far beyond the average audience. It may appear that the possibility of further graduation at the end of the picture could not be realized by the public. Could this mean that graduation is an unimportant and uncertain principle?

This assumption would be entirely wrong. The subconscious mind of the public has a judgment which is infallible. Its instinctive evaluation is by far superior to the concentrated thinking of the writer. It could be compared to a photographic film. A camera with its lens almost closed will leave hardly any trace on the film. The same film will record further designs if the lens is opened further. Even though we may photograph another subject, the film will always record other contours should we open the lens more and more. This can be continued until the sensitivity of the film is exhausted. However, the reciprocal process is impossible. After an exposure with a fully opened lens any feebler photographs will not be recorded on the film.

Our subconscious receptiveness acts with the same precision as the photographic film. It records the values of each scene with a precise sense of graduation. If there is stagnation or even reversion of the progress, it will leave a blank on our receptive mind. Our reaction is uninterest, boredom, impatience or forgetfulness.

The forward movement represents an exertion and therefore contains the danger of fatigue. If we analyze the fatigue of a human being closely, we recognize that it is only partly caused by actual exhaustion, and for the other part it is a result of the misconception of the task before us. Whether we have physical or mental exertion before us, in either case we appropriate a certain amount of psychological energy for the task, according to our estimate of the need. If our estimate was wrong, that is, if the task is more difficult than we expected, we shall feel fatigue, because the energy that we appropriated was not sufficient. If, however, our estimate was correct from the beginning, then we shall feel less fatigue despite the fact that we are confronted with the very same exertion.

Again let us use the example of the man on the highway. If the distance before him is two miles, he will be able to walk faster without fear of exhaustion; if it is thirty-four miles, he will have to cut down his speed considerably, in order to save his strength. If he did not know the distance, he might use the wrong speed and fall down exhausted before reaching his goal.

Translating this into motion picture terms, we find the following principle: If fatigue is only partly caused by actual exhaustion, and for the other part by a miscalculation of the task, we must enable the spectator to make a correct estimate of the distance before him. The actual exhaustion of the spectator results from the strain on his eyes and ears, and from his mental processes, as experiencing emotions, anticipation, suspense, evaluation. But this actual exhaustion is infinitely smaller compared with the fatigue through miscalculation.

It is not easy, in the motion picture, to let the spectator estimate the distance. The stage play which is divided into one or more acts often of about equal length lets us clearly distinguish the time of its ending. In reading a novel the number of pages left lets us recognize the exact distance which has yet to be traversed. Besides, the element of fatigue does not exist in the novel because the number of pages we read in one sitting depends upon our energies.

But the moviegoer can only estimate the distance if a goal has been set. Once he knows the main goal, the spectator has a continuous feeling for the distance which has yet to be traversed. He can estimate the difficulties in the way of the main intention. If the picture exceeds this estimated ending point, the spectator feels fatigue. If the end of the picture comes too early, he is left with superfluous energies which cause dissatisfaction. If no goal has been set, there is no distance which could be estimated.

After these investigations, we are in a position to balance the progression or sequence of events in the story with the forward movement of the spectator.

First of all we must cause the forward movement. But then we must arrange the sequence of events and scenes of the script in such manner that they will satisfy the forward movement which was caused.

It is true that the sequence of events must be logical and consecutive on the basis of cause and effect. But it must also be such as not to interrupt or interfere with the forward movement of the spectator.

In most pictures one can change some scenes around without any apparent damage to the action, and without any violation of the consecutive progress of time, particularly if we interpose scenes of two different story lines. Very often, scenes are changed around at the last moment; sometimes they are even reversed after completion of the picture. At times, this can be done without distorting their meaning, but it may disturb the forward movement of the spectator.

In order to guarantee a smooth forward movement, the sequence of events and scenes has to follow the interest of the spectator. The same principle was established when we found that the camera had to follow the shifting interest of the spectator.

Failure of the story to follow our interest gives us the impression of a chopped-up script. This feeling does not result from a large number of scenes, nor does it result from the fact that these scenes occur in many different places. It simply results because the sequence of scenes does not follow our interest.

Of course, if there is no forward movement, there is no interest, and the sequence of scenes cannot follow anything. All the scenes will hang loosely together without any arrangement. So the first step is to create interest and thereafter follow it.

Primarily, it is the intention of an actor which causes our anticipation and forward movement and interest. An intention necessarily prepares a following scene where this intention will be executed or frustrated. These intentions cause us to believe that the following or one of the following sets will show us the anticipated place. As common an intention as “I’m going to bed” need not be followed up because it does not create any interest. But in no event is it possible to show a man in Singapore who says, “I’m going to New York,” unless you give extensive explanation. Any intention which creates interest must be followed up. However, it is not necessary that a scene which is prepared should follow immediately. Instead, it may follow at a later moment. But this delay cannot be chosen willfully.

Our immediate reaction is to anticipate that the scene which is prepared by the intention will follow immediately. But an intention may be connected with a certain lapse of time. In that case, we are relieved from the necessity of letting the execution follow directly.

If the time element does not relieve us of the necessity of following up the interest immediately, the sequence of scenes must be immediate. Should the scriptwriter — for some reason or other — give us another scene which may possibly represent another story line, he is hindering our forward movement. This may be used on the basis of attraction and hindrance in order to make the spectator impatient. But if he fails to realize that intention or motive have thoroughly prepared another scene, and if he puts two or three other scenes in between, he may interfere with our forward movement. At the same time, he takes away all the strength and power of the interfering scenes because our interest lies in another direction, and this prevents us from concentrating upon these other events. It is very dangerous to hinder the attraction of one’s anticipation by interposing equally important scenes; that results in a splitting of our interest.

The knowledge of all the facts creating or hindering the forward movement makes it easy to find and correct any possible faults in the script. The strange behavior of motion pictures with respect to their speed has lost its mystery.