Chapter 1. Message and Medium

In this chapter we’re going to focus on giving you the facts, just the facts—the basic information you’ll need to get started on your first video production. Over the next several chapters we’ll be layering in more topics that will add to your knowledge, your experience, and the richness of your projects.

But just so we can get you up and running as soon as possible, we’re going to introduce some basic topics for you to consider before you jump in.

First, about the title of this chapter—“Message and Medium.” This is one way to break down the essence of the process you’re about to engage in: What do you want to say, and how are you going to say it?

After all, that’s what it’s all about.

What Is Video Production?

Throughout this book, we’re going to use phrases such as filmmaking, media creation, and video production interchangeably. The topics we discuss and the terms we explain are, for the most part, useful whether you’re planning to produce a visual poem, fictional film, animation, montage, documentary, training video, commercial, public service announcement (PSA), or anything else that uses moving pictures to convey a subject or an idea. At their root, despite wide variations in style, content, length, audience, and goals, all of these are just different types of content creation, which means they all have as much in common as divides them, especially when it comes to creating them.

When you make a media piece—any media piece—you are choosing an image or series of images and accompanying sounds to show something to an audience, which could be your best friend or the entire world. When your audience watches your piece, they will immediately begin to try to decode your meaning. You may not think you are “telling a story” or anything so grandiose if what you are filming is your friend’s skateboard trick.

But you are.

Even in the 20-second video of a skateboard trick, there’s a progression; something is attempted, and success or failure may result. The lowest rung of hell of content creation is probably the Cute Kitten Video. Even here in the lowest depths of media creation, your audience of cute kitten enthusiasts is going to wait and anticipate the cute thing that kitten is going to do.

Getting Started: What Do We Need?

When asked the question, “What do we need?” we usually answer, “What’ve you got?”

Before jumping into an adventure filled with gadgets, gear, and gizmos, we’d like to share a fundamental truth about telling a story through the medium of video: It’s not about the gear you use; it’s about how you use it to tell your story effectively and convincingly.

You could have the latest, most expensive pro camera on the market, but if you don’t have a good story to tell and don’t know how to use the camera, your project will be no better than the average YouTube video. Mobile devices have brought high-quality video tools into a lot of people’s pockets. A high-quality camera alone does not make a pro videographer.

Here is a general list of the intangible requirements to create successful, professional video:

![]() An understanding and working knowledge of the controls of your equipment

An understanding and working knowledge of the controls of your equipment

![]() A well-organized plan of attack

A well-organized plan of attack

![]() An ability to problem-solve calmly under pressure

An ability to problem-solve calmly under pressure

![]() An eagerness and curiosity about how things work

An eagerness and curiosity about how things work

![]() A devotion to detail

A devotion to detail

![]() An understanding of the value of safety

An understanding of the value of safety

![]() A commitment to reliability and dependability

A commitment to reliability and dependability

Most of the items on this list can be acquired only through practice and experience, but it’s not too early to get started at trying to be the person who possesses those skills and qualities.

Tools of the Trade: From Mobile Devices to Pro Gear

There are several tiers of equipment based on price, quality, and feature set. The top tier is professional-level equipment (see FIGURE 1.1), tools exclusively used for large-budget feature and television work, the type of gear you’d never hear of anyone buying because it’s so expensive that renting is the most practical way to get access to the equipment. In a professional kit, cameras in particular have fewer automatic functions but more physical access to the controls through buttons, dials, and switches.

The lowest tier is consumer-level products (see FIGURE 1.2) designed for mass market that have a cheaper price tag. Consumer equipment has most of its controls under the hood, through automatic functions that allow the user to easily plug and play without a steep learning curve.

Consumer equipment tends to produce a lower-quality product but has the advantage of having more resources for support through online tutorial videos created by other users and more responses in support forums.

In between, there are prosumer-level devices (see FIGURE 1.3), hybrids of professional and consumer-level equipment. Prosumer gear hits that sweet spot of high-end features and quality, with moderate prices. Equipment in this category definitely holds back on some controls that professional work demands. Whatever this gear lacks in controls can usually be handled by a workaround. Prosumer equipment has allowed enthusiasts and educational programs to create professional-level work without paying a hefty price tag or sacrificing control.

Choosing the Camera to Fit Your Budget and Needs

In professional applications, the purpose of a project helps determine the type of camera that is used for a production. Choosing from the variety of camera types available at affordable prices, with their assortment of features, requires an understanding of the capabilities and limitations of each type of camera.

Studio Cameras

Within television production, large studio or broadcast cameras (see FIGURE 1.4) are used because of the requirements of that type of production. These cameras allow a single-cable connection to a live switcher that includes communication to the operator and a video signal of the program choices of the director to be monitored.

Each camera has a tally light that indicates which camera angle the program is switched to so that the operator and the talent are informed. A large viewfinder display allows the operator to better detect the focus of their shot and have increased mobility.

The camera supports used for studio cameras include large tripods to support their weight and pedestals that use air or hydraulic pressure to allow the camera to easily move up and down.

ENG

Outside the studio, electronic news gathering (ENG) cameras (see FIGURE 1.5) are used for news and many other forms of video production. ENG cameras have a shape designed for comfortable placement on an operator’s shoulder for handheld use.

Unlike studio cameras, ENG cameras have a built-in recording mechanism. Before it was possible to use memory cards to record video, these cameras recorded video to cassette tapes, which made the size and power requirements of the camera much larger than any consumer camera made then or now.

Even as video formats transitioned from analog to digital, ENG cameras still required tape to record the picture and sound until tapeless acquisition became practical and affordable.

To complete the all-in-one design, ENG cameras use professional-grade microphone inputs to record audio, which is a function that is not necessary or available for studio cameras or film cameras.

Cinema

Film cameras (see FIGURE 1.6) require the operator to see the shot through an optical reflex viewfinder that forces them to keep their face in direct contact to avoid light leaking in and exposing the film negative.

Historically, their disadvantage was only one person could monitor what the camera was capturing. The invention of the video assist, or video tap, which is a small video camera built into the camera to tap into the view of the lens, allowed directors to also monitor what the camera operator was seeing.

Digital cinema cameras (see FIGURE 1.7) don’t require a video tap since they are basically a type of video camera. The use of digital cameras in cinema production started with models that looked and functioned like ENG and broadcast cameras. Early use of digital cameras in feature-film production came along with the increase in quality of smaller digital tape formats and the ability to record higher-definition images in the standard frame rate for cinema production.

Cinema cameras have begun to move away from the systems and formats of broadcast video and use new acquisition formats that take advantage of the workflow of feature film production (see FIGURE 1.8) and emphasize the need for higher-resolution images that capture a larger spectrum of light and color.

Images acquired in raw image formats and new digital cinema color spaces necessitate color correction before being delivered to a viewing audience. This extra step in the workflow makes for higher-quality images than footage shot directly in standard video formats.

A feature that distinguishes film and cinema cameras from most other types of cameras is the ability to easily switch out wide and telephoto lenses (see FIGURE 1.9). ENG and studio cameras have a single lens, usually a zoom lens, to use for every shooting circumstance. In recent years, manufacturers have begun to add the ability to switch lenses to some prosumer and consumer cameras.

Note

In the United States, the system for standard-definition video is called NTSC, which runs at a frame rate of 29.97 frames per second (fps). Feature motion pictures run at a frame rate of 24 fps. See Chapter 3 for more information on frame rates.

Camcorders

Camcorders (see FIGURE 1.10) are like ENG cameras, but for the prosumer and consumer markets. Prosumer camcorders (often called professional camcorders) record audio using professional audio inputs and have many manual and custom controls on the body of the camera.

Unlike ENG cameras, camcorders are too small to rest on the operator’s shoulder and include many more automatic functions to make operation easier for novice users. A feature that originated in camcorders and has made its way to ENG cameras is the swing-out LCD viewfinder screen. Touchscreen controls on LCD viewfinders have migrated from the consumer camcorder to professional digital cinema cameras.

Like digital cinema cameras, a certain class of camcorders has come to market that allows the switching of lenses. In video production, familiarity with various types of lens mounts and features was not required knowledge before the introduction of video-capable DSLR cameras.

DSLR

Digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras (see FIGURE 1.11) are the digital version of single-lens reflex cameras used for still photos on film. With increasing resolution (expressed as megapixels) and processing capability, digital still camera manufacturers experimented with adding video capture as a feature. This allowed the user to use interchangeable photo lenses to capture video, much like cinema cameras do.

A major advantage of using a DSLR to capture video is the price of the camera. With prices comparable to—and often lower than—the price of camcorders, these cameras can reproduce professional-quality cinematic images far beyond what most camcorders can deliver. (When pricing a DSLR, keep in mind that the accumulated cost of lenses can drive up the price far beyond the “body-only” price of the camera.)

The DSLR’s ability to record audio does not match that of camcorders or ENG cameras, so the use of dual-system sound, as used in cinema production, is required for professional-quality audio. Recording audio on a separate recorder in a dual-system sound setup requires considerations for synchronizing the audio with the picture in the editing process.

Unlike other video cameras, DSLRs lack the ability to control the zoom lens with a motorized switch, and many have limited or no automatic focus control. For the price, the quality, and their capabilities (or lack thereof), DSLR cameras make for great training cameras. Using a DSLR demands that the user have an understanding and active involvement in manipulating its controls to capture professional images.

Mobile Cameras

Even smaller than consumer camcorders and DSLR cameras are pocket camcorders that record video and sound in a device that can easily hide in the palm of your hand. Pocket camcorders are one type of camera that can be placed in the mobile camera category.

Sports and action cameras are by-products of the scale of pocket cameras and are used for capturing virtually any kind of sporting activity. They’re also used in professional cinema and television production for stunts and tricky angles. Sports and action cameras specialize in capturing in high frame rates that make movement look clearer and sharper and, when played at slower frame rates, really help demonstrate aspects of the physical world that real-time video doesn’t.

Consumer mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets (see FIGURE 1.12), have cameras that take wonderful snapshots and impressive video images. Apps dedicated to adding complete manual and custom control to mobile cameras are making it possible to consider using mobile cameras exclusively for many types of video productions. Accessory manufacturers are creating cases and mounts that convert mobile devices into cameras capable of producing sophisticated projects.

Smartphones and tablets that run apps can edit and upload video to online video-hosting services. With a single device you can write, shoot, edit, deliver, and present a video production, without introducing a single other piece of equipment into the process. The ease and low cost of doing so makes it possible for anyone with such a device to use video to deliver their message to the world.

Sound Gear

In Chapters 3 and 4 we’ll go into detail on the kind of microphones (see FIGURE 1.13) you can use for specific types of audio recording. To get a head start on equipping yourself appropriately, identify the microphone inputs and audio recording capabilities of your camera.

If your camera does not have enough audio inputs or the kind of inputs to fit the microphones you want to use, consider getting a portable digital audio recorder that records audio on memory cards, has professional microphone inputs, and even has a built-in microphone. Some portable audio recorders can be mounted directly on a camera with an output to record reference or backup audio directly to the camera.

There are even apps that let you use your phone or tablet to record high-quality audio files in the same uncompressed format that is used professionally. We guarantee this will not be the last time we mention what there is an app for.

Accessories and Expendables

Having chosen a camera—which admittedly is the most difficult choice to make in your gear selection—you still need to add a few essential items to your arsenal. Some of these items could be foregone on informal productions but never left out of a professional inventory.

Note

Take a look at the appendix for a list of our recommended camera models.

Camera stabilization tools such as a tripod, monopod, a shoulder mount, or a gimbal-based device (like a Steadicam, Glidecam [see FIGURE 1.14], or M VI) can take a novice production from looking like shaky home video to smooth, precise, high-end work.

When choosing a tripod, consider the weight of your camera. A $10,000 150mm tripod designed to hold a pro camera would be overkill if you’re mounting a smartphone on it. On the other side, a $10 photo tripod will definitely not allow you to make smooth movements with a heavier camcorder.

You never know how important batteries for your camera and audio gear are until you forget to have enough charged ones for your shoot. Never settle for the battery that comes in the box with your camera; always buy more than you think you need, and always keep them charging. Did a battery die on a shoot? Put it on the charger now.

Media such as memory cards or cassette tapes (if you’re still shooting on that stuff) is like gold. Memory cards of a high class ensure that the camera will be able to effectively write the fast stream of video data being jammed onto it. Tape is cheap; don’t reuse tapes unless you like glitches and corruption in your footage.

A clapboard, or slate (see FIGURE 1.15), is a tool that has two purposes: to visually label or slate your shot for identification during the editing process and to have a matching visual and auditory reference to synchronize picture and sound if they were recorded on separate systems. Slates are usually made of acrylic for use with a dry-erase marker, but there are even apps available so you can use your mobile device as a slate.

Tip

Tape a cosmetic pad to use as an eraser at the end of a dry-erase marker. Your marker is not a device called a mouse.

Other useful expendables and accessories include the following:

![]() Gaffer tape (cloth tape used in lighting)

Gaffer tape (cloth tape used in lighting)

![]() Gloves (slang: hand shoes) for protecting your hands from hot lights

Gloves (slang: hand shoes) for protecting your hands from hot lights

![]() A flashlight

A flashlight

![]() A multitool

A multitool

![]() Pens, pencils, markers

Pens, pencils, markers

The Poetry of Content Creation

The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. It’s not uncommon for those considering a project to wonder what to write about or how to go forward. It can all seem too big, too vague, and too undoable. It’s not. You just need to look at your project one scene, one shot, or one piece of dialogue at a time; listen to your instincts; and be honest with yourself about when you are moving in the right direction and when it’s time to switch gears.

The great composer Mozart wrote his operas and concertos in ink, supposedly never needing to change a note. Thankfully, we have text-editing programs with undo and delete keys, and when we edit on nonlinear editing (NLE) systems, we can drop in and pull out clips at will.

Don’t stress about getting it perfect. Just get it.

Here are a few things to consider as you get started.

In the Beginning

Content creation—whether it’s for a TV series, a feature film, or a documentary—is based on three universal elements that are universal.

![]() The main character, also known as the protagonist and sometimes the hero. In our examples, they are your friend the skateboarder and the cute kitten.

The main character, also known as the protagonist and sometimes the hero. In our examples, they are your friend the skateboarder and the cute kitten.

![]() The goal they go after—whether it’s the great trick (the skateboarder) or, say, a ball of yarn (the kitten).

The goal they go after—whether it’s the great trick (the skateboarder) or, say, a ball of yarn (the kitten).

![]() Obstacles to that goal, such as a lack of motor skills or the yarn rolling away.

Obstacles to that goal, such as a lack of motor skills or the yarn rolling away.

Everything we watch comes down to these three things. There are a lot of other elements, of course, but these three elements form the skeleton that everything else hangs off.

Whether you’re discussing a Jane Austen novel, The Avengers (2012), or an episode of Jackass, the universal experience of watching media is tracking something that has been established by the content creator to watch. The next time you view anything, see how long it takes for you to understand what you’re tracking.

This works differently, of course, depending on various other factors such as the length of the media. For a television show such as The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (1990–96), the whole series will track something—how street-smart Will Smith handles the changes in his life when he moves from his tough Philadelphia neighborhood to the wealthy neighborhood of Bel-Air.

Every individual episode will track this development in a general way. Additionally, it will track an individual storyline more specifically. The conflict always raises a yes or no question—say, will Will make it onto The Oprah Winfrey Show? It gives the audience something specific to root for and against. Let’s look at our three basic elements in a little more detail.

Protagonist/Main Character/Hero

These are all synonyms (words that mean the same thing) for the character we go through the story with, in other words, the one the story is about. In The Matrix (1999), Neo is the character we go through the story with, and he is most responsible for making things happen, so he is the main character. Luke Skywalker and Anakin Skywalker in the Star Wars film series are other examples of main characters. Interestingly, Anakin shows up in another Star Wars film under another name and filling another role in the story, but we’ll discuss that later.

Sometimes the protagonist in a media piece is not immediately apparent. At first glance, Frodo Baggins appears to be the main character of the Lord of the Rings series of books by J. R. R. Tolkien and films by Peter Jackson, when he has to decide how to dispose of the One Ring, a weapon of great power.

However, over a protracted series of adventures, Frodo’s pal and gardener Sam Gangee really fills out the role of the protagonist better than Frodo. Although Frodo ultimately has to get to Mount Doom to destroy the ring, Sam does pretty much all the heavy lifting to get him there across something like 8,000 pages of books. Frodo mainly wears a ring, which may be good enough for the protagonist of Project Runway but not Lord of the Rings.

One of the most important things do as a writer/creator is to let the audience know what kind of person (or fish, in Finding Nemo, 2003) your protagonist is. What do they care about? What are they good at? What are their weaknesses? Getting to know the main character is often the first thing that gets an audience interested in a story. You may notice, the next time you watch a show or film, that some aspect of the protagonist’s personality is showcased the very first time we meet them.

Often, the protagonist in a film or novel will have a special skill that will help him or her to achieve the goal. For example, Luke Skywalker in Star Wars (1977) is a great pilot, a skill he uses to try to destroy the Death Star. He also has The Force, which is like two special skills, so maybe he’s a little greedy in the special skill department.

The hero of the story may be the protagonist and the protagonist may be a hero, but not always. In Lord of the Rings, the most traditionally heroic character (brave, good fighter, good-looking, and so on) is Aragorn, but he is not the protagonist because he is not the one we most identify with or the most central driver of the mission. Walter White in the television show Breaking Bad (2008) and Tony Montana in the film Scarface (1983) are not heroic, for the most part, but they are definitely the protagonists of their narratives. Protagonists don’t have to be “good guys/girls”; they just have to be relatable and interesting.

Goal

The goal is the thing that the main character most wants to achieve. This can involve beating the villain and/or solving the problem or threat. Goals may change during the story, but usually only if they become deeper, more intense, or richly meaningful to the protagonist.

For instance, Luke Skywalker’s initial goal in Star Wars is to save Princess Leia. Once the pursuit of that goal concludes, around halfway through the film, the story could be over, except that the quest to rescue her has uncovered a great and immediate threat to freedom throughout the galaxy (bigger and more intense goal).

In Breaking Bad, Walter White starts out making and selling drugs to provide money for his family after he dies from cancer (immoral albeit arguably noble goal). When his prognosis improves, he continues building his drug empire anyway because this new quest delivers him the respect and greatness he has been denied in life (a selfish albeit interesting goal).

Most goals in stories are surprisingly simple, though they don’t always start out seeming that way. They’re usually things that a large portion of the audience (if not the whole audience) also might want—money and treasure, of course, but also deeper things—love, respect, a purpose in life, freedom.

Goals can generally be broken down into external and internal goals that can come from the same result. For instance, in the film Rocky (1976), Rocky Balboa wants to “go the distance” in his fight against Apollo Creed (external goal) because that will give him back the self-respect he has lost (internal goal).

Conflict/Obstacles

These are whatever might stop the protagonist from achieving his/her goal. Examples of this include Shrek the ogre’s self-esteem in Shrek (2001), that Jack and Rose are from different socioenomic backgrounds and also that their ship hits an iceberg in Titanic (1997), and that Juliet’s family is at war with Romeo’s in Romeo and Juliet.

Most writer/creators like to have at least a pretty clear picture of who their protagonist is, what their goal is, and what the obstacles might be before they start writing their stories out in detail. Once you have all three of these things, you can begin to generate empathy for your main character. If farmers are in the business of producing crops or dairy products, storytellers are in the business of producing empathy.

Empathy

Empathy is the feeling the audience has that we want the protagonist to win and/or survive. We want that skateboarder to finally nail that trick. We want that kitten to get that ball of yarn. We root for Walter White to beat the even more bad, bad guys in Breaking Bad.

The writer, director, actor, and everyone directly involved with the project make us feel that we know the character or even that we are the character. The more we identify with the protagonist, either because they are like us or they are what we aspire to be, we don’t go to movies to watch other people go through things; we go to experience these things ourselves. This, above all, is the magic trick that propels us out of our seats and into the screen or at least the theater.

Some of the most common ways the writer and director create empathy for the main character include the following:

![]() Having the main character go after a goal that is almost impossible. Examples include Luke Skywalker taking on the Empire, El Mariachi having to fight dozens of hit men in El Mariachi (1992), and Rocky wanting to last 12 rounds against the heavyweight champ of the world.

Having the main character go after a goal that is almost impossible. Examples include Luke Skywalker taking on the Empire, El Mariachi having to fight dozens of hit men in El Mariachi (1992), and Rocky wanting to last 12 rounds against the heavyweight champ of the world.

Sometimes in our own lives, reaching our goals seems impossible, so we identify with a character who charges ahead against serious odds like we want to do ourselves.

![]() Having the main character experience a great loss. For example, in Spider-Man (2002), Peter Parker loses his beloved Uncle Ben. El Mariachi loses his great love.

Having the main character experience a great loss. For example, in Spider-Man (2002), Peter Parker loses his beloved Uncle Ben. El Mariachi loses his great love.

In the course of our lives, the most traumatic moments are frequently the most vivid and memorable. Most of us become better friends with others by choosing to open up about losses we have endured. Just so, we identify with characters in narratives when we see them go through loss because we all know what it means to experience loss in our lives.

![]() Having the main character experience a great need. Examples include Rocky’s need for self-respect. In The Sixth Sense (1999), the protagonist is a child psychologist who has a great need to redeem himself for a past mistake.

Having the main character experience a great need. Examples include Rocky’s need for self-respect. In The Sixth Sense (1999), the protagonist is a child psychologist who has a great need to redeem himself for a past mistake.

![]() Having the main character be brave, like Ana Garcia in Real Women Have Curves (2002) when she chooses to defy her mother; funny, like Austin Powers in the Austin Powers franchise of films; or decent, like attorney Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) are the kinds of personality traits we respect in each other.

Having the main character be brave, like Ana Garcia in Real Women Have Curves (2002) when she chooses to defy her mother; funny, like Austin Powers in the Austin Powers franchise of films; or decent, like attorney Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) are the kinds of personality traits we respect in each other.

![]() Having a puddle splash up on the main character. We all have bad days.

Having a puddle splash up on the main character. We all have bad days.

Empathy creates engagement and identification between us and the protagonist. It locks us in with them for the rest of the story. Vince Gilligan, the creator of Breaking Bad, as well as the producers and distributors of that show, took great risks by having Walter White act more villainously than perhaps any protagonist in history.

They risked having the audience lose empathy and turn against their character and their show. But their gamble paid off, and the result was one of the most ambitious, successful, and talked-about series in the history of television.

The 12 People (11 Plus the Protagonist) You Meet in Stories

A good next step when writing your story is to think about the types of characters who will populate your narrative. In this section we’ll describe some of the most common types of characters in narratives.

As we stated earlier, you definitely want a protagonist for your audience to identify with as they pursue their quest. That is a job that definitely needs to be done in your story.

But there are other jobs that routinely need to be done as well. One way to develop your project is to think of a “Now Hiring” board. Ask yourself, what kinds of characters does your story need? The following are some suggestions for your jobs board.

Antagonists and Anti-heroes

The antagonist is the character who most gets between the main character and the goal: the mother who doesn’t want her daughter to marry below her means in Titanic, or the replicant (cyborg) who simply wants to extend his synthetic life in Blade Runner (1982). The antagonist is not always a villain, but if the story does feature a villain, the villain is probably the antagonist.

Can the villain be the protagonist? There have certainly been lots of cases where writers and directors have switched it up. Anti-heroes are villains we root for despite their illegal or immoral activities, and they include some of the richest characters in media history, including Michael Corleone in The Godfather series, Walter White in Breaking Bad, and pretty much every protagonist in the genre of film noir.

Even the relatively innocent genre of family films have explored the anti-hero in Despicable Me (2010) and Megamind (2010), where traditionally villainous characters take on the role of the hero, usually attempting some sort of redemption.

The Mentor

Sometimes the main character has a mentor, an older advisor who gives them some knowledge or training they’ll use to achieve the goal. Examples of mentors include Morpheus in The Matrix, Uncle Ben and Aunt May in Spider-Man (2002), Gandalf in Lord of the Rings (2001), and Obi-Wan Kenobi in the Star Wars movies.

One of the most interesting mentors ever is Hannibal Lector, who some misremember as the antagonist of The Silence of the Lambs (1991) because he was more villainous than the actual villain (serial killer Buffalo Bill). But Lector actually illuminated the thought processes of the antagonist for the protagonist, FBI agent Clarice Starling. The Lector character proved so popular, in fact, that he graduated to the position of antihero in later films and a television series.

Mentors frequently die once they have dispensed their learning to the protagonist, reflecting the essential circle of life. We learn from our elders, and then our elders are gone, and we live on as they have taught us. As in life, so in media. Deep, right?

The Ally/Allies

Sometimes, the hero has an ally or second hero who wants the same goal for a different reason and whose personality, strengths, and weaknesses are different from the main character’s. Examples include Quint the shark expert in Jaws (1975) who is interested in catching the shark not because he shares the protagonist Sheriff Brody’s need to protect his Long Island town but because sharks are his obsession. Han Solo in Star Wars also wants to rescue Princess Leia like Luke Skywalker does, but for money. An ally is occasionally revealed in the course of the story to be a traitor character (more on that later).

Mirror

Mirror characters are similar to the protagonist; they often seem like brothers or sisters. They may be allies or competitors/obstacles. They exist to show us the “dark side” of the protagonist, so we can see what the story would be like if they chose the path of evil, or the “poor” existence of a “rich” character, so we have something specific to worry about if their plan doesn’t succeed.

Han Solo is a mirror character to Luke Skywalker. Eddie Brock is a mirror character in Spider-Man 3 (2007). Like Peter Parker, Eddie is a photographer for the Daily Bugle; also like Peter, he is transformed into a superbeing, the villainous Venom.

One of the most interesting mirror characters in literature and film comes from No Country for Old Men (2007), based on the novel by Cormac McCarthy. The seeming protagonist Llewelyn Moss is shown to be the mirror character in one of the most staggering sequences in cinema history, forcing us to rethink the entire story.

The Henchman

The henchman is the ally of the antagonist. Oddjob, the well-dressed assassin who sliced off enemies’ heads with a razor-tipped bowler hat in Goldfinger (1964), remains one of the great Bond henchmen. Recently, the minions in Despicable Me (2010) have proven so popular as henchmen that they are trading up to the big chair for a new film.

The Love Interest

A love interest is a kind of ally (though they don’t technically have to be, as we’ll explain later) who also provides a romantic storyline. Memorable examples include Trinity in The Matrix, Lois Lane in Superman (1978), and Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind (1939). In some cases, the romantic storyline is the main story; in others, it is supporting. In David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly (1986), reporter Veronica Quaife is a love interest, ally, victim, and antagonist to the main character.

The Sidekick

The sidekick is a kind of ally who generally provides humor (or brightness contrasted to the protagonist’s darkness). C3PO and R2D2 in Star Wars, Jimmy Olsen in Superman, and Cosmo Kramer from Seinfeld (1998) are examples of outstanding sidekicks.

The Traitor

The traitor is an ally who turns against the protagonist, usually reversing the likelihood of success when they leave. SUPER SPOILER ALERT: When Cypher in The Matrix gives the location of Morpheus’ ship to the Agents, things turn grim for Neo and company. Elsa in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) betrays Indy, making her both a love interest and a traitor.

Traitors can go both ways. Mini-Me starts out as a henchman for Dr. Evil in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), but after a squabble, he joins the hero’s side as Mini-Austin.

The Bureaucrat

The bureaucrat is a character who represents the status quo, the way things are done, and as such is an obstacle for the protagonist. Sometimes the bureaucrat can be mistaken for the antagonist, but they are more of a roadblock than a true adversary.

Pretty much all police captain characters, most judges, and all DMV workers represent the bureaucrat character. Die Hard (1988) alone has several great bureaucrat characters: Dwayne Robinson, the Deputy Chief of Police; Thornburg, the reporter; and FBI agents Big Johnson and Little Johnson. This gives protagonist John McClane ample opportunity to be, as he says, “just a fly in the ointment, Hans. The monkey in the wrench.”

The Victim

The victim represents the potentially dire outcome of the story if the protagonist does not achieve the goal; for instance, Nemo in Finding Nemo might be lost if his father cannot find him. The victim can also be the love interest (Lois Lane in Superman), an innocent child (Dana’s baby Oscar in Ghostbusters II [1989]), or, frequently, the protagonist.

As we indicated earlier, characters can “change jobs” throughout a story, more than once as the writer/creator sees fit. One of the most interesting examples of this is Quentin Tarantino’s omnibus masterpiece Pulp Fiction (1994), which is made up of several stories involving the same characters. In one storyline, hit man Vincent Vega is the protagonist; in a second, he is the sidekick; in a third, he is a henchman.

Once you have considered the characters you want to populate your story with, as well as their goals and obstacles, you will need to organize all the steps of the quest the protagonist will undergo to achieve their objective.

Three-Act Structure

The three-act structure is the set of rules for all storytelling, from movies and television to novels, plays, and short stories. Following these rules allows writers and directors to present the information the audience needs in the most intriguing order.

The first rule of the three-act structure is that all stories can be broken down into three separate and distinct parts—previously, you may have referred to them as the Beginning, Middle, and End, but here they shall be known as follows:

![]() The first act (usually around the first 25 percent of the story)

The first act (usually around the first 25 percent of the story)

![]() The second act (approximately the middle 50 percent)

The second act (approximately the middle 50 percent)

![]() The third act (the final 25 percent)

The third act (the final 25 percent)

In the next three sections we’ll define the three acts in a traditional narrative structure.

The First Act

Here we find out the setup: when and where the story takes place, such as Philadelphia in The Sixth Sense or the future in The Matrix. The first act also introduces the circumstances that pertain to the story, such as a young woman deciding whether to leave home to attend Columbia University in Real Women Have Curves, or the first voyage of the world’s largest ship in Titanic.

In the first act we meet and learn important facts about the life and personality of the protagonist, especially their strengths and weaknesses. In Titanic, Jack is poor but full of life, while Rose appears wealthy but feels dead inside. In Die Hard, John McClane is a tough cop who won’t give up in, but he desperately wants to get back together with his wife and children.

We also learn what the goal will be and get a hint at least of what threat or problem might prevent the protagonist from achieving it, such as a plague, an asteroid, a serial killer, or an iceberg. Also, we either meet or learn about the villain or antagonist or a bureaucrat on whom we can focus our dislike on when the “villain” is a volcano or an asteroid.

You can also think of the threat as the antagonist’s goal, which is usually the opposite of the protagonist’s goal. For example, in Speed (1996), the threat is that a bus will blow up if it goes below 50 miles per hour; therefore, the hero’s goal is to make sure that doesn’t happen so he can save the passengers.

Once we’ve met the protagonist and we know what the goal will be, we’re ready to move from the first act into the second act. The moment when the protagonist accepts the challenge of achieving the goal is called the first act break. Examples include Luke deciding to leave his planet to try to save Princess Leia in Star Wars; Rocky agreeing to fight the heavyweight champion of the world, Apollo Creed; or the terrorists taking over the building in Die Hard (which forces John McClane to try and stop them).

The first act break is the moment when the main character becomes locked into their path and the audience knows what the rest of the movie is about and what the goal/threat is.

The Second Act

The rhythm picks up and the pace increases once we move into the second act. The main character now tries to achieve their goal but encounters a series of obstacles that get in their way. Obstacles can include the following:

![]() The loss or death of family/mentor/allies: Dr. Crowe, the child psychologist, grows apart from his wife in The Sixth Sense; Luke loses mentor Obi-Wan in Star Wars.

The loss or death of family/mentor/allies: Dr. Crowe, the child psychologist, grows apart from his wife in The Sixth Sense; Luke loses mentor Obi-Wan in Star Wars.

![]() Personal injury, either physical or mental: El Mariachi loses his hand; Luke also loses his hand in The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Personal injury, either physical or mental: El Mariachi loses his hand; Luke also loses his hand in The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

![]() The threat turns out to be much worse than originally thought: The shark in Jaws is much bigger than expected; the computers in The Matrix seem omnipotent; the Death Star in Star Wars is the greatest weapon the universe has ever known.

The threat turns out to be much worse than originally thought: The shark in Jaws is much bigger than expected; the computers in The Matrix seem omnipotent; the Death Star in Star Wars is the greatest weapon the universe has ever known.

![]() The original method of defeating the villain/threat doesn’t work and/or only makes the threat more serious: The shark overwhelms Sheriff Brody and his team at first in Jaws because the sheriff has underestimated it; first the Air Force and then nuclear weapons fail against the aliens in Independence Day (1996).

The original method of defeating the villain/threat doesn’t work and/or only makes the threat more serious: The shark overwhelms Sheriff Brody and his team at first in Jaws because the sheriff has underestimated it; first the Air Force and then nuclear weapons fail against the aliens in Independence Day (1996).

As you’ve probably noticed, the two emotions that successful stories activate in the viewer are hope and fear. We hope the protagonist will achieve their goal, and we fear that they will not.

The second act usually involves a series of ups and downs in which some events (new information/training/a fresh ally) will bring the protagonist closer to the goal, while other events (loss of the clue/a betrayal/an injury) will push them further from the goal.

The ups and downs of the story are most often reflected through a series of twists, reversals, and false hopes. When the U.S. military brings in nuclear weapons in the film Independence Day, it gives the audience a false hope that, at least by using such an extreme measure, the aliens can be defeated. In The Sixth Sense, when we realize that a major character has been dead all along, this is a twist that changes what we have believed so far to be true. When El Mariachi gets knocked out and taken to Moco, his situation is reversed; he goes from being on top of the situation to a captive.

The main thing about the second act is, things get tougher for the main character, whether they are looking for love or trying to save the world. Our empathy for the main character grows as their situation gets worse.

They try to solve the problem, but their first solutions don’t work for whatever reason, and now when things get worse, we get to see what our heroes are really made of. As they continue to try to achieve their goal when it seems more impossible than ever, we really like them, and we want them to succeed.

Eventually, though, some combination of perseverance, resourcefulness, smarts (the main character’s strengths), and sheer luck, the main character catches a break that will enable them to possibly defeat the antagonist or resolve the conflict. This moment in the story is called the second act break. It usually happens around 75 percent of the way through the story, and it takes us from the forward momentum of the second act to the even faster momentum of the third act.

The second act break might feature any of the following:

![]() The main character finally figuring out how to stop the antagonist/threat. For example, Luke and his crew find a weakness in the plans for the Death Star.

The main character finally figuring out how to stop the antagonist/threat. For example, Luke and his crew find a weakness in the plans for the Death Star.

![]() The protagonist figuring out when the threat will climax—for instance, when will the lava hit midtown L.A. in Volcano (1997)? This is also called a “ticking clock.”

The protagonist figuring out when the threat will climax—for instance, when will the lava hit midtown L.A. in Volcano (1997)? This is also called a “ticking clock.”

![]() If the hero’s goal intensifies during the second act (Star Wars) or changes because of a new understanding of the circumstances (The Sixth Sense), the second act break is the moment when the last piece of the puzzle is in place and the protagonist knows what they must ultimately do—for example, help a young boy cope with his abilities in The Sixth Sense, or fly onto the Death Star and destroy it in Star Wars.

If the hero’s goal intensifies during the second act (Star Wars) or changes because of a new understanding of the circumstances (The Sixth Sense), the second act break is the moment when the last piece of the puzzle is in place and the protagonist knows what they must ultimately do—for example, help a young boy cope with his abilities in The Sixth Sense, or fly onto the Death Star and destroy it in Star Wars.

At this point, the audience knows what, when, and usually where and how the big scene/“big showdown” will occur.

The pace picks up as the second act break takes us from the second act into the third act because this is the first time the protagonist has been sure of what they need to do to finally achieve the goal.

The Third Act

The third act features the big showdown between the protagonist and antagonist or the big get-together or final goodbye in a love story. The main character must finally go all out with an act of great bravery in a drama or action movie or an act of honesty and compassion in a love story.

Often the showdown, also called the climax or climactic scene, will involve the hero overcoming a weakness that’s been discussed since the first act. In Jaws, Sheriff Brody, who is afraid of water, gets dumped in the ocean to fight the shark in Jaws. In Die Hard, John McClane must do the only thing he finds impossible: opening up to his wife. Superman must overcome kryptonite.

Sometimes, the hero must make a great sacrifice in order to achieve their goal: El Mariachi loses his hand, Jack sacrifices himself to save Rose in Titanic, driller Harry Stamper gives his life to save the earth in Armageddon (1998).

After the climax, the hero has won or lost (usually won), and there’s been a resolution or result, most likely the accomplishment of the goal or perhaps a new understanding or enlightenment. For example, when Luke blows up the Death Star, the resolution is, the Rebels are saved. When Jack sacrifices his life in Titanic, the resolution is, Rose is saved and will remember him always. When Austin Powers defeats Dr. Evil, he doesn’t get his mojo back, but his story is resolved because he realizes he doesn’t need it after all.

Occasionally, there is a difference between what the protagonist is trying to achieve and what the writer/creator (and the audience) feels they need. For example, we never believe that Lloyd Christmas should wind up with Mary in Dumb and Dumber (1994), though that is his stated goal. Yet, this does not make us lose empathy for Lloyd. Remember, empathy is based on our hope for the main character, so in this situation, we hope Lloyd will realize what he truly needs, which is to be honest with Harry and appreciate his good friend.

Finally, after the climax, there’s usually a shot or scene that lets us know things will be okay going forward. We get to enjoy a little downtime with our new best friend, the protagonist. For example, Hooper the shark expert and Sheriff Brody paddle back to shore in Jaws amid bits of exploded shark; the survivors back on Earth mourn Harry Stamper in Armageddon.

This final wrap-up after the conflict has been resolved is called the denouement.

Jobs and Crew Positions

Once a writer/director has a story to tell, they need a crew to help them tell it. In this section, we list some of the most common jobs in media creation. In some cases, we just give a brief description here and then more information in later chapters when we focus more in-depth on a particular job.

For those who have never considered doing any of these jobs, in most cases we are going to suggest the personality type that typically suits the job. None of these is an absolute or exclusive precondition for any job described, but they should help get your process started finding the best job for you.

Executive Producer

The coordinator or overseer of the entire production, the executive producer (EP) chooses the project and arranges the financing. They may work for a studio, own the script of underlying property, or in some way be responsible for getting the movie made.

Personality type: The executive producer, like a writer, must have or choose a story or big idea that will take over their lives for a substantial amount of time. They should be active readers and viewers and have a sense of the audience or marketplace for whatever project they are choosing to focus on. They must have the business sense to analyze whether the project they have chosen to develop will be competitive in whatever arena it will screen in, as well as the drive to put together the best possible team to produce the project.

Producer

The producer is a day-to-day boss responsible for making sure everyone else is doing their job. Their responsibilities include the following:

![]() Assigning responsibilities to individual crew members and checking to make sure they will complete tasks correctly and on time

Assigning responsibilities to individual crew members and checking to make sure they will complete tasks correctly and on time

![]() Arranging the shooting schedule location by location

Arranging the shooting schedule location by location

![]() Making sure everything needed to film is ready on schedule

Making sure everything needed to film is ready on schedule

Personality type: The producer needs to be extremely organized and able to juggle several issues at once. They must have good planning skills and predict where challenges to their success will come from, solving problems before they erupt.

Writer

The writer visualizes the plot and theme; creates the characters, visual descriptions, and dialogue; and communicates with the director and occasionally the actors about specific aspects of the story.

Personality type: The writer needs to have a good vocabulary and a visual, descriptive imagination.

Director

The “creative boss” of the movie, the director does the following:

![]() Transforms the script into a series of images or shots that can be filmed and turns thoughts and ideas into pictures and performances. They have to hold the whole project in their head to make sure everything that is filmed will all work together well.

Transforms the script into a series of images or shots that can be filmed and turns thoughts and ideas into pictures and performances. They have to hold the whole project in their head to make sure everything that is filmed will all work together well.

![]() Creates or oversees storyboards and shot lists to let crew members know what the shots are.

Creates or oversees storyboards and shot lists to let crew members know what the shots are.

![]() Casts actors who can give the necessary performances.

Casts actors who can give the necessary performances.

![]() Rehearses the actors and crew, giving them constructive feedback

Rehearses the actors and crew, giving them constructive feedback

![]() Oversees the creative process of the film from preproduction through postproduction

Oversees the creative process of the film from preproduction through postproduction

Personality type: The director needs to be a natural leader, visually and verbally creative, and focused on getting the job done; they must also supportive of people they work with. They deal mostly with the actors, director of photography, camera operator, and producer. All other work on the production is channeled through the director.

Actors/Talent

Actors play one or more onscreen roles in a project. An actor is responsible for the following:

![]() Creating a character including a backstory for their character, or the life that the character lived before the project began. Actors are responsible for developing their role both in the way they look and in the internalized thoughts and emotions they have, reacting spontaneously and believably as the character.

Creating a character including a backstory for their character, or the life that the character lived before the project began. Actors are responsible for developing their role both in the way they look and in the internalized thoughts and emotions they have, reacting spontaneously and believably as the character.

![]() Practicing and memorizing all dialogue.

Practicing and memorizing all dialogue.

![]() Practicing and memorizing their scenes, including their movements or blocking.

Practicing and memorizing their scenes, including their movements or blocking.

Personality type: Actors must be really focused to shut out all the “noise” and stress on a set and just let themselves become that other person they’re playing. They should have good memorization skills and commit themselves, in a mature way, to the things they do. Good actors, like good writers, have active imaginations and love coming up with new things every time they take on a new role. Actors interact mostly with the director and other actors.

Script Supervisor

The script supervisor (also known as the continuity supervisor) is the official note taker onset and is responsible for making sure that the script is filmed in its entirety or for noting why anything is changed in the dialogue or the description as filming progresses. The script/continuity supervisor deals mostly with the director since they help keep the director on task and make sure all of the shots and takes will have good continuity when the editors cut it all together.

Personality type: The script/continuity supervisor must be observant and take good notes.

First Assistant Director

The first assistant director or 1st AD, also known as the boss of the set, runs the set and makes sure everyone is doing their job and staying on schedule. They develop call sheets so that everyone knows when and where they need to be.

Personality type: This crew member must be tough and have good discipline and natural leadership skills and be a good motivator to help eliminate problems that can slow a crew down. The 1st AD deals mostly with the director and the producers.

Cinematographer/Director of Photography

The director of photography (DP, or DoP in the United Kingdom), also known at the cinematographer, is in charge of the look of the film and the way light and shadow are used to help create the tone or feeling of a movie. They choose the type of film to create the appropriate look as well as equipment to control or shape the light. The DP works mostly with the director and the camera operator.

Personality type: The DP must have good visual imagination and be visually creative and artistic.

Camera Operator

The director designs the shots, but the camera operator must record the shots; therefore, the camera operator must have especially good communication with the director. The cameraperson is in charge of maintaining the composition or framing, the exposure, and the focus of the shot.

Personality type: The camera operator must be responsible and reliable and like working with and learning new gear, as well as steady and focused.

Camera Assistants

Camera assistants, or assistant camera (AC), are in charge of the various responsibilities related to the preparedness and use of the camera, including the following:

![]() Transporting the camera gear (camera, boom pole, microphone, slate, and so on) to the location and back

Transporting the camera gear (camera, boom pole, microphone, slate, and so on) to the location and back

![]() Making sure they have all camera gear including slates, dry erase markers, lens cleaner, and so on

Making sure they have all camera gear including slates, dry erase markers, lens cleaner, and so on

![]() Marking the slate before each new take

Marking the slate before each new take

![]() Pulling/changing focus during the take for the camera operator, as needed

Pulling/changing focus during the take for the camera operator, as needed

![]() Making sure camera batteries are charged

Making sure camera batteries are charged

Personality type: The camera crew must be reliable and responsible and like learning how to use complicated equipment.

Gaffer

The gaffer handles the electricity on the set if need be. Professional productions use a lot of electricity for lights and other equipment, so this is an important job where safety is the absolute number-one priority. Student and amateur crews don’t always have gaffers but must still be focused on safety whenever dealing with electricity.

Personality type: The gaffer is like Batman on the set. They both wear gloves, feature an amazing tendency to get the impossible done, and have utility belts. Only gaffers’ utility belts feature a lot of tape, including gaffer’s tape. How cool is it that your job has its own kind of tape?

Key Grip/Grips

The key grip is the boss of the grips. This is the team that builds up or breaks down the lighting rigs used to film scenes based on the DP’s wishes as well as any other gear used by the camera crew such as the dolly. The grip team reports to the key grip and their assistant, the best boy.

Personality type: Grips get it done; they set it up, and then they break down the riggings and other lighting gear, which can be hung far above the stage or set. Grips are primarily involved in assuring the safety of everyone on the set. They listen well and ask what needs to be asked.

Production Designer/Art Director

The production designer collaborates with the director to make sure everything bought or made for the film (props, costumes, sets) contributes to the right mood or tone of the film, whether silly or serious. The art director works for the production designer and oversees the art department, making sure everything is created to the exact specifications of the design plan.

Personality type: The production designer and art director must have good visual imaginations and be especially demanding before saying that something is right for the film.

Costume Designer/Prop Master

Like the production designer, the costume designer and prop master collaborate with the director and actors to come up with the right clothing and onscreen objects for the characters to use when filming.

Personality type: These designers must like shopping and have good visual imaginations and be especially demanding before saying that something is right for the film.

Make-Up Artist/Hair Stylist

Make-up artists and hair stylists work with the director and actors to achieve whatever make-up and hair effect is appropriate for the scene, from simple everyday stage make-up to prosthetic effects.

Personality type: Make-up and hair stylists in media are extremely competent and passionate about what they do yet generally upbeat and pleasant to work with. They are often the ambassadors between the crew and the cast and must keep themselves familiar with trends in make-up and hair but also be knowledgeable about different styles through history and different cultures. They must be ready to style characters from different eras and ages. This is a lucrative discipline where those with a personal interest should consider a program to learn how to develop into a professional.

Production Sound Mixer/Boom Operator

The production sound mixer must get a great audio recording of the action on the set, typically focusing on the voices of the actors and then the background sound of the location. They must choose the proper microphones and recording devices to get the best, cleanest sound and analyze every location beforehand for potential problems such as buzzing in the background, street noise, or anything else that might impact recording.

The boom operator collaborates with the production sound mixer, wearing headphones so that they can hear the recorded sound and holding the boom pole and microphone over the actors’ heads while they are saying their lines at such an angle pointed down at their mouths so that their voices are clear and easy to understand.

Personality type: Both these positions require good hearing; additionally, the boom operator should have strong arms as they may have to hold the boom pole over their head for several hours a day while focusing on the sound quality.

Editor

The editor reviews all the footage and cuts the movie either on film or, increasingly these days, using a nonlinear editing (NLE) software such as Avid Media Composer, Adobe Premiere Pro, or Final Cut Pro X. The editor functions as the director’s second set of eyes, working with the director to create the final finished version of the movie.

When possible, the editor should watch on the set to make sure the director is giving them footage they can cut together well.

Personality type: The editor must have extremely high and exacting standards and a lot of patience to look through hundreds of takes of shot after shot trying to find “it”—the perfect balance, rhythm, and cut point to perfect the scene. Editor is one of the main jobs that leads to directing.

Assistant Editor

The assistant editor (AE) creates the edit log or list of all the available footage (aka dailies). The assistant editor is in charge of bringing in all the media into the editing system and organizing it for the editor to easily find and use it. They also may be called on to edit some of the scenes.

Personality type: The assistant editor likewise must have a lot of patience and concentration and be detail-oriented. On a two-hour feature film with a 10:1 shooting ratio (footage shot, length of piece), assistant editors have to log (list) and maintain a mere 20 hours of footage, but assistant editors on reality shows must sort through massive amounts of material, with ratios of 40:1 to 100:1 or more.

Sound Editor

Sound editors cut the music, sound effects, and rerecorded (or “looped”) dialogue (ADR) into the film.

Personality type: Sound editors, like video editors, must like working with computer programs. They often have little interaction with the rest of the crew except for the director.

Music Supervisor or Composer

The music supervisor helps the director choose prerecorded music that matches the feeling of the scene or comments on it in an appropriate way. Alternately, a composer writes and plays music specifically written for the film.

Music is a key component of a successful project, often conveying the emotion that the script or performances sometimes hold back on.

Personality type: The music supervisor or composer must have a sharp ear and a keen sense of how to choose or compose music that captures and amplifies the tone of each scene.

Publicist

The publicist determines the best strategy for getting the word out about any screenings or exhibition of the finished work enough in advance so that a substantial audience can build. Depending on the budget of the project, the publicist may create flyers/posters or other materials related to the movie in Adobe Photoshop or buy ad time on radio and television or buy ad space in print and on the Web.

Over the last 15 years, social media has become key to successful promotion of a media piece, with most sizable productions creating a website that users can link to through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or some other well-trafficked site. The publicist might also organize parties or other social events to promote the project.

Personality type: Publicists should be visually minded and active in social media, and familiar with Adobe Photoshop and other design-oriented software.

Production Assistant

The glue of any production, the production assistant (PA) is an all-purpose utility player who may be called on to help out with any job that needs doing, from assistant camera to art department to assistant producer. This is the key entry-level job on real Hollywood films and television production companies, both as office PAs and set PAs.

Personality type: A good production assistant is reliable and always looking for something to do to help their movie.

Production Workflow: The Three Ps

In video production, there are three main stages of the process of creating a project: preproduction, production, and postproduction. Don’t be fooled by the production-centric titles; each stage is as important as the other. Some jobs on a project are limited to one stage of the production, while the leading positions stay with a project through all three stages.

Preproduction

The preproduction stage begins when a decision is made to create a project and goes through until the start of the production stage. The steps that occur in preproduction include but are not limited to the following:

![]() Writing the script

Writing the script

![]() Budgeting the entire production

Budgeting the entire production

![]() Scheduling the shoot

Scheduling the shoot

![]() Fundraising to meet the budget

Fundraising to meet the budget

![]() Hiring the crew

Hiring the crew

![]() Casting the talent

Casting the talent

![]() Scouting locations

Scouting locations

![]() Designing and building sets

Designing and building sets

![]() Rehearsing

Rehearsing

![]() Renting equipment

Renting equipment

Production

The main phase of the production stage is principal photography, when the bulk of the shooting takes place. It is also where the majority of most projects’ budgets are spent. The length of the principal photography depends on many factors, such as intended running time of the project, the size of the budget, and—most importantly—the final deadline.

Additional photography, in the form of reshoots and pickups, is also part of production. Reshoots are done if there is an error or a change to a scene that can’t be fixed by any means other than to shoot the scene all over again. Pickups are additional shots that are necessary for the scene that were not captured when the scene was originally shot. Reshoots and pickups can occur as part of principal photography or during postproduction.

Postproduction

Postproduction (or post), as the name states, is the stage after production, but it doesn’t necessarily have to wait until production ends to start. The management and organization of media, the assets and material that make up the images and sound that are put together, frequently occurs as the production stage is still happening.

Picture editing is the first phase of post, and in most circumstances (live production excluded) takes a longer time than production. Simple projects that have little to no visual effects (VFX) have a smaller number of people working than the production stage requires. A project that has visual effect shots, such as adding background elements over a green screen or animations in the foreground, requires more crew members in post.

Postproduction also includes work on audio, titles and graphics, and color correction.

Note

There is industry slang used throughout each stage of production, and each one has a story behind it. To honor the memory of camera assistant Sarah Jones, whose life was cut short in an on-set accident in 2014, we call the first shot of the day the Jonesy.

One More P: Protocol

When setting up a shot, there is a standard order or protocol that a crew must follow for maximum efficiency. Before any equipment is set up, the director and talent use the stage or location space to block the action. Once the actors are blocked and rehearsed, the camera or cameras are placed for the first shot of the day.

Once the camera is placed, the grip and electric department get to work on lighting the shot. In cases of large or complicated lighting setups and shooting in a studio, the set is prelit for efficiency.

As final tweaks are done to the lighting, the sound crew can position their microphones, making sure they are not seen by camera nor cause any shadows in the shot.

Tip

The 1st AD might want to ask, “Is anyone not ready?” Asking this is more likely to get a response from someone making a final change that needs just one more minute than asking, “Is everyone ready?”

A full camera rehearsal takes place for all elements to be blended together before cameras roll. The talent aren’t the only ones who have a script with lines to say, the crew does, too! Once everything is working in full rehearsal, the director calls out, “Lock it up.”

The 1st AD says, “Quiet on the set, picture up!”

“Picture up” is short for “the picture is up,” which means the cameras are about to roll.

At this point a camera assistant holds the slate or clapboard in the shot with the sticks open, ready to mark.

Once the set is quiet, the 1st AD calls, “Roll” or “Roll sound.”

The sound mixer (or recordist) starts recording and says, “Speed!” That means the audio recording machine has taken up speed. This is a holdover from the days of analog audio recording where a reel-to-reel recorder took a moment for the motor to get to its proper recording speed.

Note

When numbering scene numbers on a slate, use uppercase letters to be easily recognized. Also, the letters I and O are skipped to avoid confusion with the numbers 1 and 0.

The camera operator starts recording and also calls, “Speed,” “Camera rolling,” “Camera rolls,” or just “Rolling.”

The camera assistant then verbally slates the shot by saying the scene number and take, for example for scene 3B take 2, the AC would say, “Scene three-baker, take-two.”

Before hitting the slate, the AC says, “Marker.” If there are separate slates for different cameras, the AC will say, “A-camera mark” or “B-camera mark” before hitting the slate.

The marker is called before hitting the slate, not after, and certainly not during. The purpose of the slate is to synchronize the picture and audio. The sound of the clapboard needs to be clearly heard so the editorial team can match it up to the picture frame where the sticks meet each other.

Tip

If there is a mistake made while hitting the slate, the AC needs to call, “Second sticks,” before hitting the slate again.

If there is no audio being recorded, the AC holds their fingers between the sticks to show the editing team that there is no associated audio to search for. Shooting without synchronized audio is called MOS.

If talent or crew are still a little antsy, the director might call for everyone to “settle” before calling, “Action!”

Then the magic happens. When the take is done, the director calls, “Cut.”

To keep things moving, it’s important that the director immediately state their intentions to either shoot another take or move on to another shot. To shoot another take, the director says, “Back to one,” which means back to first position, where everyone was when the shot started. If the take is good and no other take is needed, even for safety, the director or 1st AD can call, “Moving on.”

Then the cycle continues again and again, until the last shot of the day, which is called the martini shot. We’ll leave it up to you to figure out why it’s called that.

The Shot: Composing for Meaning

The placement of the camera and the type of lens used do a lot to help tell your story. When motion pictures got into the storytelling business at the start of the 20th century, directors just placed actors in front of the camera and had them act. The result was a filmed play, and the camera was mostly used as a recording device.

These days, media creators use the camera in countless ways to add energy to a scene or to comment on the action. Here are some things to think about when deciding where to put your camera.

A shot here is defined as a camera angle—move the camera or change the lens and you’re changing the shot—and it can be defined in many different ways as you will see. Here are some preliminary definitions and categorizations.

Shots Defined by Size

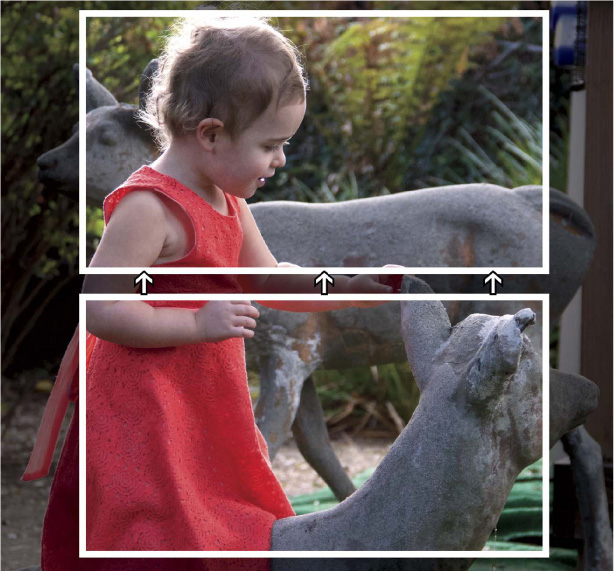

Some shots are defined by width, or the lateral range of subjects or action captured in the frame. Each shot plays a role in the sequence of shots that comprise a scene, is a part of the way one or more subjects are framed, or determines where the director wants the audience’s attention focused at a given time (see FIGURE 1.16).

Wide Shot (WS)

A wide shot is a short-lens shot used to establish space, as in a master shot, or a whole location, as in the opening of a film (see FIGURE 1.17). One of the key things video producers want to do, especially in the beginning of their project, is to establish where it is taking place and then again, once the location changes, to reestablish that.

Full Shot

A full shot gives a full-body view of the subject (see FIGURE 1.18). The top of the frame is slightly above the subject. The bottom of the frame is just underneath the subject’s feet. The shot allows the viewer to see the relationship between the subject and the location of the scene.

3/4 Shot

A 3/4 shot (pronounced “three-quarter”) is slightly closer than a full shot (see FIGURE 1.19). The bottom of the frame cuts off at around the knees. The shot is loose enough to see enough of the subject’s full body movement, without bringing attention to the placement of the subject in the surrounding space.

Medium Shot (MED)

A medium shot is a head and upper-body shot, where the bottom of the frame cuts off at around the waist of the subject (see FIGURE 1.20). It may be considered the workhorse of media creation since many directors use it most commonly to handle dialogue-heavy scenes. More than 50 percent of most films are medium shots.

Medium Close-up (MCU)

A medium close-up is like a medium shot, showing the head and the upper body, yet the bottom of the frame cuts off a halfway between the waist and the shoulders (see FIGURE 1.21).

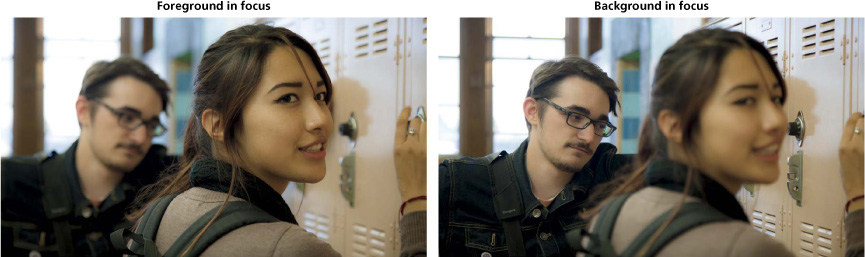

Close-up (CU)

In a close-up, the face of the character fills the frame, with the bottom of the frame cutting off right below the subject’s shoulders (see FIGURE 1.22). This brings the audience very close to the character in a way that can seem uncomfortable or claustrophobic, which is why it is mostly saved for scenes of emotional importance or to convey suspense.

Extreme Close Up (ECU)

A macro lens is used to magnify something in extreme close-up (see FIGURE 1.23) and make it fill the screen, for example, an ant on someone’s skin or a blade of grass. Showing the audience something closer than they would ever typically see it can have a disquieting effect on the audience. This was used to great effect by filmmaker David Lynch in the opening of his film Blue Velvet (1986).

Long Shot (LS)

The main action is far away from camera in a long shot (see FIGURE 1.24). This makes the audience look into the shot to figure out what is happening, and it can also be used to contrast a character with their environment, as in the magnificent pullback crane shot in Gone with the Wind in which Scarlett O’Hara is searching for a doctor when she is suddenly confronted with the terrible breadth of the destruction of Atlanta.

Two-Shot

The two-shot can be an MS, CU, or WS where two characters speak to each other and both their faces featured in the shot (see FIGURE 1.25).

Over-the-Shoulder (OTS)

This is a type of two-shot used frequently for conversations. Over-the-shoulder shots are generally done in pairs, each one focusing on a character on one side of the frame and the listener’s shoulder on the other side as if the camera was sitting on it like a parrot on a pirate (see FIGURE 1.26).

Shots Defined by Angle or Lens Height

Besides an eye-level shot, where the lens is at the same height as the subject’s eyes, there are labels for shots that look up, down, or in a rotated view at the subject.

High-Angle Shot

The camera is above the subject in a high-angle shot, which is frequently used to emphasize the smallness of the character and make it seem like the world is out to get them (see FIGURE 1.27). One example of this would be a frightened little leaguer stuck deep in right field from the point-of-view of a ball coming toward them.

Low-Angle Shot

In a low-angle shot (see FIGURE 1.28), the camera is below a character looking up at them, to make the character seem more powerful, as in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) when everyone’s favorite time-traveling cyborg “borrows” a biker’s duds and steps into shot leathered up to the tune of “Bad to the Bone.”

Oblique Shot/Dutch Angle