Chapter 3. Marrying the Story with the Aesthetic

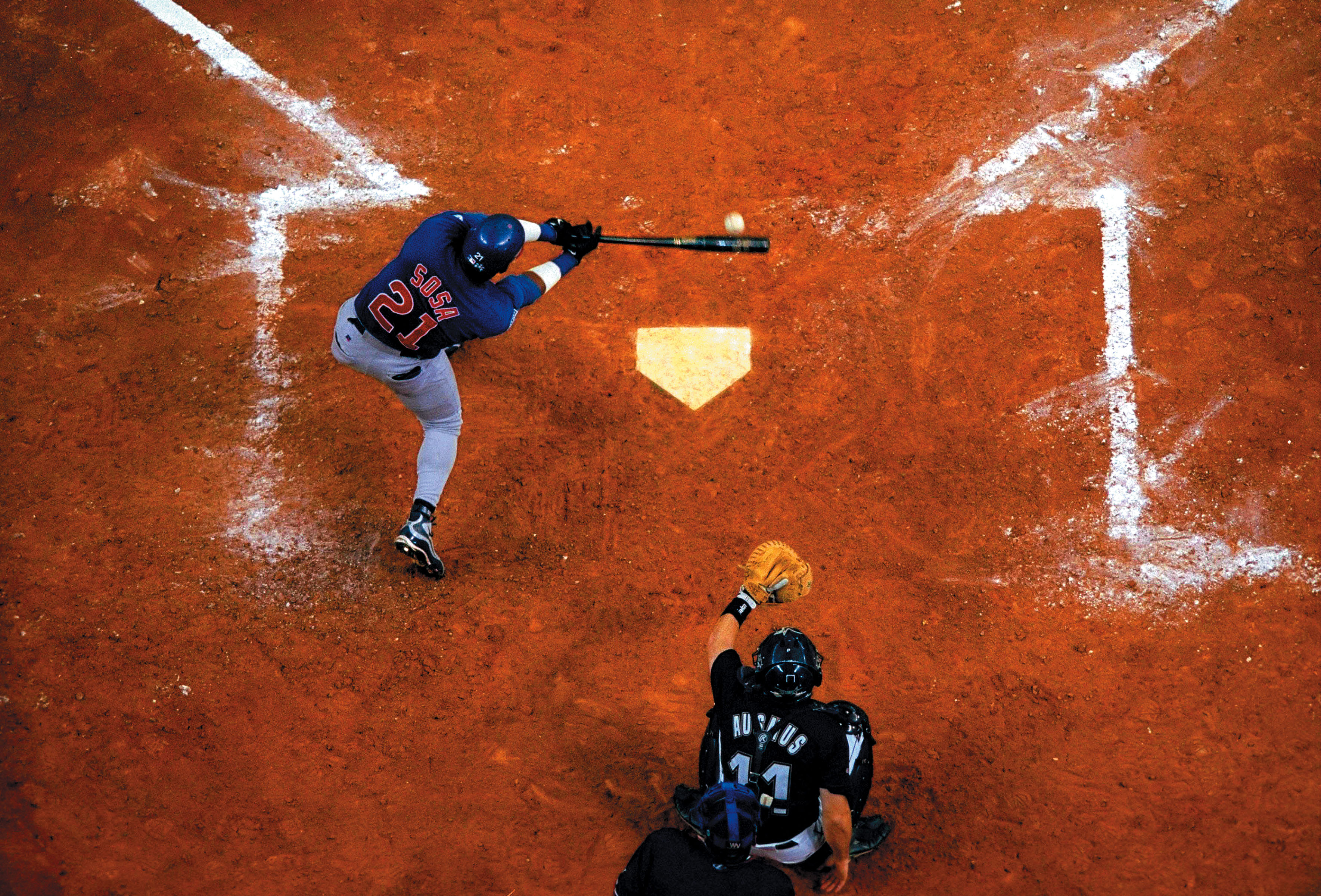

Right fielder Sammy Sosa of the Chicago Cubs swings at a pitch during a game against the Houston Astros at the Astrodome in Houston, Texas (1998).

f/28 1/800 400mm

There were a lot of things happening in 1998, but during the summer of that year, it was all about baseball and the home run competition between Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire. Along with dozens of other photographers, I was at the Houston Astrodome in anticipation of Sosa hitting his 66th single-season home run.

And though the event promised to be historic, the venue was horrible.

Photographers were relegated to two wells, our only options for photographing home plate. Our creative choices were thus limited to shooting either tighter or looser. And the background offered nothing but two big television cameras hulking behind Sosa. I was stuck.

I had photographed in venues across the country, and this was by far the ugliest stadium, from the ground perspective, that I had seen. This was one of the first domes in baseball. Fluorescents, which didn’t help the aesthetics, illuminated the field. So it was easy to justify the potentially bad results by thinking I had 65 other home run pictures that were just beautiful. This photograph was destined to be a total dud.

But then I looked up and saw there were catwalks just above home plate, so I started to negotiate access to it. I did so by striking a deal with the photographers from the Chicago Tribune and the Houston Chronicle to replace a roll of film in each of their remote cameras on the catwalk.

This decision to shoot from the catwalk rose not from my desire to want to make an overhead shot, but rather from my refusal to make terrible pictures.

This photograph for me is not just about the historic moment, but also about careful composition and geometry. Perspective lines lead almost perfectly out of the corners of the image directly into the batting zone. The home plate repeats those patterns. And there’s a right angle formed by the batter. It’s a very geometrical image.

The fact that Sosa’s arm is positioned almost perfectly parallel to that rectangle helps create a sense of balance. You also have this pristine uniform and all this mess of chalk and dirt. And of course, the pinnacle of it is that the only circular element is the big white ball. The perfect combination of ball and bat meet over home plate, and becomes Sammy Sosa’s historic 66th home run.

The action and the name and number on the back of Sosa’s uniform tell the story, but it’s also a beautiful photograph. This is how I would paint it if I could.

This was a very big turning point in my career, where I stopped following the press pool and accepting where I was going to shoot from and making the best of it. The image was going to be terrible.

Instead I looked to create my own solution, to make a better image.

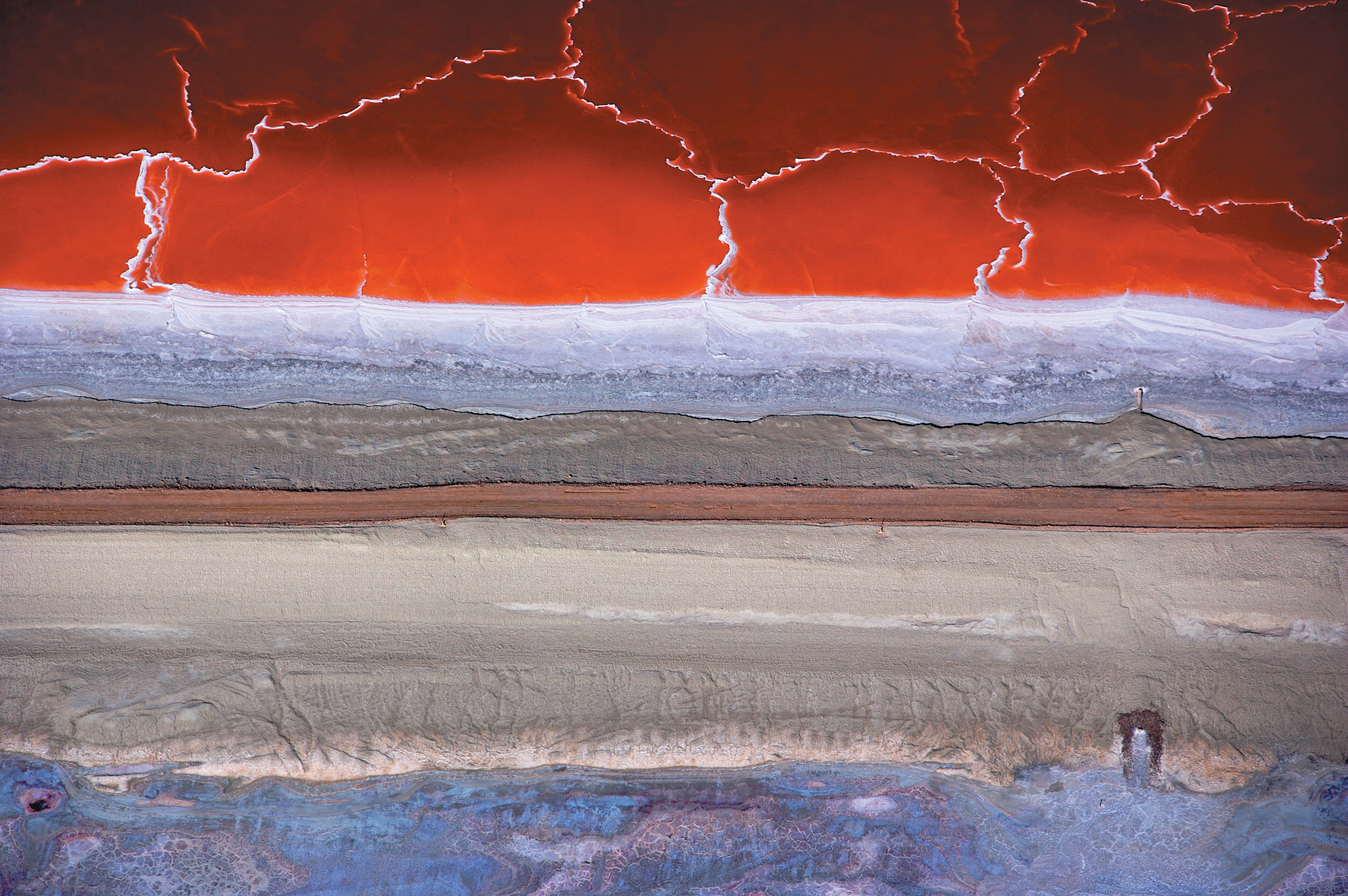

An aerial view of the wasteland that used to be Owens Lake, California (August 2007).

ISO 100 f/5.6 1/600 200mm

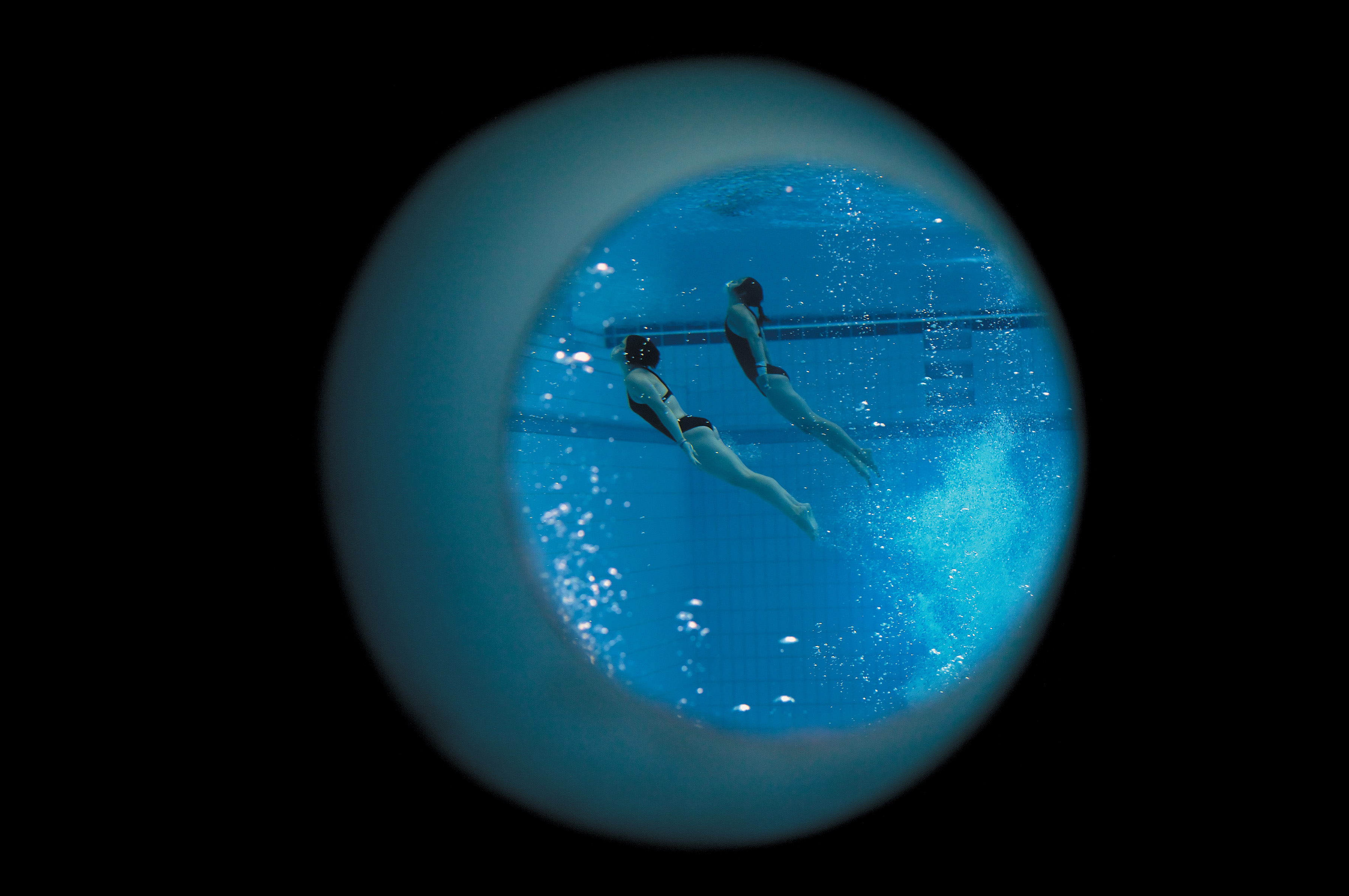

Underwater at the Women’s 10m synchronized diving competition (2008).

ISO 500 f/2 1/1600 50mm

The way to make great photographs demands more than just aiming for the best.

The Real Secrets

I developed my skills as a photographer shooting sports, but when you are shooting at the professional level, the reality is you are in competition with hundreds of the world’s best sports shooters, all of whom are jockeying for position and trying to outperform one another. They are creating amazing images as well as playing a high mental game, a game that you can’t possibly win.

The secret is to stop competing with them; you can’t win playing their game. You’ve got to play your own game, but it’s not an easy thing to do.

The newspaper just wants the picture that tells the story, and it’s something you can often deliver if you play it safe.

For a while I did just that and the paper was happy. They were in hog heaven, because most of the images going into the paper were being shot by their staff photographers. These weren’t photographs taken by a competitor or the wire service. They were mine.

But I found myself not feeling happy with those photographs. I didn’t want to look at them again. It just wasn’t enough to me that I’d gotten an image and it had run in the paper. So what? There were hundreds of other photographers shooting the same event, and they all had similar versions of what I had captured.

So the challenge for me was to tell the story but also to look at the frame as if it were a painting, to look at each photograph as if it were something that could be framed and displayed at a museum.

If I have any secrets, it is that the way to make great photographs demands more than just aiming for the best. It’s actually about being able to say no to all the mediocre or good pictures that are out there. It’s the ability to persist in the pursuit of the best photograph. That is the real secret.

From the air, you appreciate your world in a very, very different way, and you have a very different relationship to your three-dimensional environment.

A Proud Moment

Though I’m often recognized for the many aerial images that I made while at the New York Times, I have to say that the paper never had the resources to send me up on a helicopter to take pretty images.

I generally had what I called my laundry list—I had to shoot stadiums, I had to shoot for real estate assignments, you name it, but I always tried to shave off 10, 15 minutes at the end of the one-hour flight and find an image that might just make it into the Metro section or, best, onto the front page. One such time, as we were flying back from an hour-long flight in a helicopter, I asked the pilot to take a quick detour through Central Park on the way to West 30th Street to the heliport where we landed. That’s when I saw the skating rink.

What I first saw were shadows of people. From the air, you appreciate your world in a very, very different way, and you have a different relationship to your three-dimensional environment. I remember seeing these shadows kind of swimming around, and we were turning around in circles seemingly forever, for a good two to three minutes, waiting for that one moment. It happened when that one skater did a pirouette and just kind of solidified the image.

This photograph wasn’t associated with any particular story or historic event, but it’s one of the images I’m most proud of from when I worked at the New York Times. Photo editor Karen Getinkaya and I convinced them to put it on the front page.

The New York Times’s front page is the most expensive real estate in the news business, and they generally only put newsworthy images there. There is no news value whatsoever in this image. It’s just a photograph documenting everyday life, but it’s a very beautiful graphic image, and it showed up huge on the front page. I was proud of it because it showed that the New York Times could respect the value of an image even when the emphasis was more on the aesthetics than just its news value.

Skaters at the Lasker Rink in Central Park are dwarfed by their shadows in this aerial view taken February 22, 2004.

ISO 400 f/4 1/1000 70-200mm

Three cowboys share drinks and conversations by a fire at the end of the day’s work in Waimea on the Big Island of Hawaii for an essay on the Hawaiian cowboy, or paniolo, in January of 2006.

ISO 400 f/2 1/2 24mm

Taking Risks

Near the end of an exhausting two-week shoot for a commercial client on the paniolo, or Hawaiian cowboys, I casually asked the paniolo shown here if they ever got together when they were not actually at work. They said they often get together over bonfires at the end of the week. I asked them if they’d mind if I photographed them, and they agreed.

So they started their fire and they had their drinks. My goal was to find an angle where the geometry felt right. So, there’s that diagonal line falling through the image. There’s the classic silhouette of the cowboy in the foreground. There’s the cowboy resting on the left and the other one stoking the fire.

On a technical level this photo was shot at ½ second at f/2. So only the person at the center is sharp, and I shot at this slow shutter speed so you could see the embers flying off the edge of the flames. There was very little light, but to me this represents what if felt like after a demanding two-week shoot. They were tired and I was exhausted. It was time to let go and relax.

I thought this was a very important image as part of the series to show that these paniolo who work very hard during the week yet have a very blessed job, also have this camaraderie among them. It’s not easy work, but it easily beats a lot of jobs out there. There’s a sense of freedom that you feel when you look at that image, and I think that the long exposure adds to that.

There was a risk in shooting the image this way, especially by making the choice not to use flash. The reality was that most of the shots I made that night were out of focus or soft due to motion blur. But I wouldn’t have gotten the image that you see now, if I hadn’t risked failure.

To me, this image represents a pure moment of Americana. It’s a nostalgic look at the cowboy that we all have imagined. So adding artificial light is somewhat counterintuitive to me. Having the scene lit by nothing but the fire is appropriate and lends to the purity of the moment. That’s why I shot it that way. There is nothing better than beautiful natural light.

This image isn’t technically perfect, but I think we can pursue perfection to a fault. We photographers pay attention to the rule of thirds and technical directives. We try to get the highest pixel count and the most dynamic range. Yet at the end of the day all that perfection can lead to failure, more times than not.

You have to have a healthy respect for this desire for perfection, yet it has a very good chance of sucking the life out of your photographs.

As a photographer, particularly a photojournalist, you are constantly reminded that though life can be devastating and terrible, for the most part it is beautiful, and that beauty can be found in the familiar and the ordinary.

Beauty in Action

Sports imagery often revolves around the action, the key play, but there’s also a potential for strong, graphic beauty even in the midst of a photographing a challenging, even dangerous, sport.

This image speaks strongly to the power of an aerial photograph’s ability to capture the beauty of nature. People see surfers all the time from the ground, but when you shoot directly down, you can see how absolutely gorgeous that water is and the relationship between the human being to the size of those waves. You can clearly see how small those surfers are relative to the power of nature, and how dangerous and beautiful it all is at the same time.

The photograph marries the liveliness of the white foam with the contrasting calm of the dark water. It also marries the beauty of that water with the danger of what they are doing. So in many ways the aesthetic and the content are playing against each other. It’s a graphically pleasing image, but it also gives you a clear idea of what these guys are engaged in.

Beauty can be found in the familiar and the ordinary. It’s just a matter of opening your eyes. There are few things more satisfying than capturing that beautiful moment, when things line up just right, and making an image that reveals the beauty of the everyday.

Surfers practice in the days leading up to the Rip Curl Pipeline Masters in 2006.

ISO 200 f/5.6 1/2500 700mm

Photographing What Isn’t There

When I was offered the assignment to return to New Orleans a year after Katrina had hit, I didn’t want to go. In fact, I was so reluctant to go back that I told my editor that I would rather be sent to Iraq than go back to New Orleans.

I was so afraid of what I would find there. The initial story had been so emotionally draining that I was worried that going back a year later and seeing a tremendous lack of progress would throw me into a tailspin. But I did go, and took this shot, an image I wouldn’t have made when I was younger.

One of the hardest things to do as a photographer is shoot emptiness, or shoot something that’s not there but which conveys what is beneath the surface. As a younger photographer, I was always looking for that moment, that thing. This is a subtle image that’s actually packed with information.

What this particular image says is, here we are a year later. The vegetation has grown back. There are the remnants of two homes on the back left, but there is nothing rebuilt, and these concrete stairs and stoop are the only things left of the house that once existed here.

You can see the brand-new levee behind, in the background, and new electrical poles. So the infrastructure has been rebuilt. It shows that the 9th Ward region is virtually a ghost town: it’s really speaking to the remnants and the lack of progress. When I look at this image, I feel a tremendous amount of emptiness at the thought that that whole neighborhood is gone. The people are gone and the houses are gone. There is still news value there, because again it’s about the levee.

Concrete steps are all that remain of a house in this tilt-shift photograph made in the Lower 9th Ward on August 24, 2006—one full year after Katrina devastated the area.

ISO 100 f/5.6 1/160 45mm

It takes a lot of guts to take a picture of nothing and expect people to feel what I was feeling. It brings the image to a whole new level. Often I tried to make images that popped off of the page. This is more of a style of image that you might see shot with large format for a museum. It’s not so much a newspaper or magazine photograph, but it speaks to my evolution as a photographer. After years and years of making what could be called “banger” images, I was striving to make something more poetic and subtle.

Try as you might to ignore that lower 9th Ward, it’s still there. Politicians might not want tourists to go down there, not allow residence to go there. That loss of that community is still there. Sadly, it’s represented by that stoop.

Your approach to an image should speak to what you are trying to see and what’s there, and in this case, 99 percent of the photographers are going to walk right past it and not even notice it’s there. It’s a very unspectacular image. It’s not meant to pop off the page, and it’s an image that you are only going to get if you study it and think about it.

Besides the choice to shoot that image with a tilt-shift lens, which helped throw the tree out of focus, the image doesn’t involve any major technical feats.

It’s unspectacular in the way it was shot, but it’s an image that welcomes risk because it invites the viewer to completely miss it or to actually study it or ponder it a little bit more.

Images are happening around you every second. You can photograph anything in a million different ways, but what I always try to remember is to photograph something as if I’ve discovered it for the first time. And if I have photographed it before, I find a way to see it as I’ve never seen it before.

A trio of golfers completes their round of golf at the Cog Hill Country Club in Lemont Illinois, just south of Chicago on August 7, 2007.

ISO 320 f/3.5 1/1250 110mm