CHAPTER twelve

Dubbing

What Is Dubbing?

Dubbing actually means mixing the sound for a project. However, over the years for most people it has come to mean dialogue replacement after the final edit of a foreign film, television series, or other media project. Dubbing is replacing the original language of a film with another language, as in English to Spanish or Spanish to English. That’s the way we use the word in this book. Good dubbing today looks like the story was recorded in the language you hear, even though that is not the original language in which the project was animated. Most voiceover artists create an audio character before the animators draw the characters to match the performance. That’s called prelay animation. A dubbing artist matches his performance to the completed work. The advantages are that the actor can see a complete character and personality on the screen, but the actor has to try to match the mouth movements and the pacing that is already there while dealing with ADR technology. The art and craft of the dubbing artist is being able to take a deep breath and let the words flow out of an animated character’s mouth. This chapter focuses on dubbing: where it’s done, what skills are needed, how to get work, the process, actor challenges, synchronization of dialogue, sound effects, anime, the part that budget plays, and advice from directors and other actors.

Where Is Dubbing Done?

Animation is made internationally and distributed to other countries, dubbed into other languages either in their country of origin or after distribution. The dubbing is done in major cities around the world. Los Angeles is a big dubbing capital as some dubbing is done there for animated films and cartoons that are made in the United States and shipped around the world. Dubbing is done there as well on anime that comes into the country from Japan. Not all American films and cartoons are dubbed in the United States. Some are dubbed after leaving the country. The countries called “the FIGS” (France, Italy, Germany, and Spain) dub basically everything that comes into their countries. Rome is a major dubbing city, as is Paris and Madrid. Because Europeans are used to viewing dubbed motion pictures, dubbing is accepted there more easily than it is in the United States. Richard Epcar, who has worked as a dubbing supervisor for DreamWorks and Universal all over the world, says, “You have about ten times more people in your talent pool in Europe than you would in the United States ….”

Germany also has a large dubbing industry, as most of their imported films are shown in dubbed versions in the theatres. Dubbing is done in Berlin and Munich, as well as other German cities. Many dubbing facilities in Germany are large. The industry is big enough that it has its own annual awards show, called the German Synchronizing Prize. The average German dubbing artist completes 300 takes a day. German actors often do a single line and then the cutters cut it into the sound track later. Because of a problem with pirating, German actors no longer get the films to take home and watch in advance as they used to do.

With its own large film industry, India dubs many animated films and cartoons. Major films and Indian cartoons, which are originally made in Hindi, are often now dubbed into regional languages as well. Some of the larger Indian production companies have their own dubbing departments, where they produce a single program in a number of languages, both for Indian audiences and for distributing abroad. Cartoon Network in India has a Hindi language channel.

Claudia Motta has been playing Bart Simpson in Mexico for ten years. She doesn’t believe in imitating the American actress, but gets into the personality of the role. Mexico has a large dubbing industry with competition from Argentina and Venezuela. Sometimes the Spanish-speaking countries use a neutral Spanish dialect so that it works well in Spain, Mexico, and all of South America.

In China, companies rush to get the adaptation and dubbing done so that the film can be released quickly before the pirated versions are available. Working days can be long.

Digital cinema should increase the number of dubbing markets, as the soundtrack is not married to the film as it is in 35 mm, and you can have distinct soundtracks. That versatility will make it easier to dub more versions.

Dubbing Can Be Big Business

Major international stars such as Antonio Banderas, who speaks Spanish fluently, are loved around the world. Antonio was cast as Puss in Boots in the Shrek movies. Asgeir Borgemoen is well known in his native Norway and so is Masatoshi Hamada in Japan. Both are voice actors who dub major roles into their own languages. Shrek the Third was dubbed into thirty-six different languages, including the languages of smaller markets such as Bulgaria and Slovenia.

Filmmakers look at the cost of dubbing a film and then at the money they’re likely to lose if a film isn’t dubbed into the local language. Not all animation is dubbed when it goes to another country. Some smaller countries accept films and cartoons in the original language and simply add subtitles for their local audience. Subtitling is much less expensive than adding a new voice track.

For a major film such as Shrek the Third, the international casting process may start early on. On this film, DreamWorks supplied detailed descriptions of the characters and their voices to Paramount Pictures International (PPI). Then PPI contacted their local offices in the countries where the dubbing was done. Sometimes the local office used a local celebrity; sometimes they cast a local experienced dubbing actor. PPI believes that what is important is that the voice is right for the character rather than that the voice matches the English language voice. Once again for Paramount this was a business decision: If you are paying more for the talent, does the publicity generated offset the extra cost? Paramount actually had a coordination team that worked closely with voice talent from around the world. This team worked on DreamWorks and Nickelodeon films. Jeffrey Katzenberg signs off on each major casting decision on dubbing for DreamWorks films.

What Skills Do I Need?

The most important skill is acting ability. Actors need a clear voice and good diction. You have to be one with the character you’re dubbing. You need the ability to act at least as well as the original actor and, in a few cases, better. It’s just as important to breathe life into a dubbed version as it is in the original. Actors need to know voice placement. Directors often like to match the original language voice as well as possible in pitch, timbre, and personality or attitude. Some actors go to great lengths to imitate the original artists in every way. They need to be able to keep that voice and personality consistent. Cartoon dubbing artists need a flexible voice, as one artist may dub many characters. Voice-over artists should be completely uninhibited. Actors need an open mind. Like other voice actors, dubbing artists need to be familiar with the vocabulary of the business. They must be able to understand what is needed and follow direction instantly. They must be able to understand the process. Actors need a good retentive memory. They have to be able to work quickly. Dubbing artists need a good command of the target language, which includes a proficiency in pronunciation and grammar and a knowledge of colloquialisms. They need some familiarity with the cultural differences between the two countries — the country of origin and the country that is receiving the new language version of the animated film or cartoon. A background in the study of languages is helpful. An actor with a good language background can sometimes suggest a phrase that syncs up better than a phrase in the script that isn’t working. A background in singing can help train the voice.

Director Raul Garcia looks for good acting. He looks for sincerity. He looks for actors who will treat the audience (the kids) with respect. It’s not important to him that an actor match the placement of the original English language voice. In trying to match the English language celebrity voice he looks for “the spirit and the energy rather than the quality of the voice.” Raul says, “Trust the director and trust the project … Animation is completely different to what live action is. The requirements for animation are very different, and the production, the way we work in animation, will require the actor to be more flexible and be a little more trusting in the process.”

How Do I Get Work?

In the United States, normally, the agents who handle voice-over artists also handle work for dubbing artists. The field is narrow; not many voice actors can do the work and so most actors who do dubbing know each other. They may refer friends. Directors may request actors they have worked with before. Engineers may refer actors that they worked with before. But you really need an agent in order to be considered a professional by others. And you need an agent who will get you work.

Maureen O’Connell, an American actress who started her dubbing career in Spain, learned on the job. She had already acted in a series of plays in the United States when she arrived in Madrid. She had American and English actor friends in the Spanish film community, and one of them referred her to a dubbing director when he was casting. There was no audition. She started the Spanish into English walla session with no previous dubbing experience. It was sink or swim. She was singled out to do some wild lines here and there. Because she was able to sync, spoke clearly, and could work quickly and efficiently, she passed the on-the-job test. She was hired back for more demanding roles. Since she was able to do her work well and quickly with only a couple of takes, she was able to support herself there as a dubbing professional, dubbing live action principal roles and working with directors such as Ingmar Bergman. It was not a large dubbing community. One director would recommend her to another director. Referrals from directors there got her work here in the United States, including her work in dubbing animation.

Do I Get a Script before the Session?

Ordinarily, actors do not see a script before the session. They go in cold. There was a time when actors were occasionally sent a copy of the original film for viewing prior to the dubbing session. But as pirating became such a large problem, that practice was stopped. Once the actor arrives for the session, he is given a script in the language that he’s going to be using for the dubbing. Some companies use fourteen-point type in the script to make it easier for the actors. Actors place their scripts on their music stand in a way that their eyes can go from paper to screen quickly.

If the actor has been hired to do only walla scenes (wild lines in group scenes), then he’ll probably not get a script at all. He’ll most likely be required to improvise his own lines appropriate for the group scene he’s recording, which means talking when the group on the screen is talking and refraining from talking when the group is quiet.

The Dubbing Process

At the dubbing session there will be a director, who is probably the one who’s adapted the script from the original language and written the dialogue. He may be responsible for postproduction as well. Sometimes there will be other actors at the session. Sometimes an actor may work alone.

The section to be dubbed is projected onto a television or film screen, digitally or looped, in a way that can be replayed over and over again. The actor finds the passage in his script, preferably memorizes it, and watches the screen to see how his passage matches the mouth movements. Sometimes there is a rehearsal before the first take, but not always. The goal is to do a good take in one or two tries, not fifteen or twenty. When Saban Entertainment was dubbing anime, they considered twenty dubs per hour to be the norm for actors.

A couple of synchronization systems are used in the United States. The most common is three beeps in a rhythm before the passage. The actor starts speaking on the fourth beep. Another system uses a system of flashes on screen instead of beeps. You should be able to find the time code in one corner of the screen. The exact time that the dialogue starts and ends may be written in the script:

When Maureen O’Connell was in Madrid, Spain, they used a different system with a single slash across the screen. The actor started speaking on the slash.

France and Canada often use another method. Voice for clarification actors watch colors at the bottom of the screen rather than the actor’s mouth and use the colors to conform their dialogue to the length of the words. If they’re not watching the actor, then they can’t see the expression on his face. Some people have trouble using this system.

Actor Challenges

1. Synchronization in a couple of takes. You are usually allowed to be off by one frame, if necessary. Content is usually considered more important than the technical aspects of the match.

2. Being able to memorize the line quickly so that you can focus on the screen.

3. Giving a good acting performance, not just a mechanical voice replacement.

4. Producing a clear voice with good diction and pronunciation.

Bigger Actor Challenges

1. Doing a character in a voice that is not your own, portraying another character (for instance, a villain playing a clown in a play).

2. Finding another way of saying something when the dialogue in the script doesn’t sync properly. If the writer is there at the dubbing session, you may volunteer a substitute tactfully. If you need to add syllables, words such as “hey” or “oh” can be added before a line.

Synchronization

Languages are all different. For instance, when you’re dubbing English into Spanish, you normally have to begin a fraction before the dialogue and end a fraction after because Spanish words are longer, typically, than English words. Indian actors say that it’s very difficult to dub fast-talking street-wise black actors into Hindi for the same reason. The words must fit into the space allotted for them in the language of origin.

The important thing for an actor to watch for is the labials. These are letters like b, m, p, wh, and w, where the lips go together to impede the breath. Lip – teeth consonants like f and v are also important.

There is a rhythm to speech. You look for and match that rhythm.

Of course, the dialogue should have the same meaning that the original has. Ideally, it should have the same beauty of language as well. This is mainly the translator/writer’s job, but if you have an idea to make it work better, you might suggest it.

In almost every project there is what one actress called “The loop from hell.” Things will be going smoothly, and then one loop just won’t work properly. Often no one seems to know exactly what the problem is or how to fix it. Maybe the writing is wrong, maybe the actor is having a problem with something, or maybe it’s the fault of the director, but it just isn’t working. Then finally someone will make a small adjustment and it all falls into place.

Today most countries around the world use Pro Tools software, which can move a line and expand or contract it for a closer sync. The use of Pro Tools has made it possible to make the fit so exact that a dub can look like the dialogue was originally recorded in that language.

The Mouth

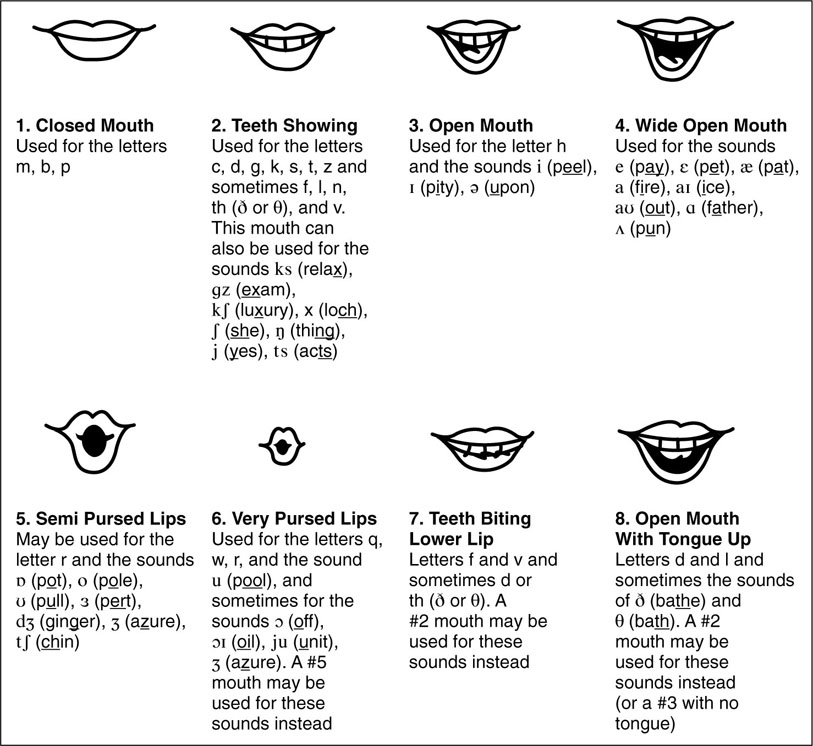

Television animators who animated in 2D had mouth charts to simplify the way a mouth looked when it pronounced certain sounds. Different studios had slightly different systems. At Hanna-Barbera we only had six different mouth positions to represent the English language. Animators at Disney, who animated feature films, had a bigger variety.

A. This was a closed mouth and represented the sounds of the letters m, b, and p.

B. The teeth showed in almost a smile. This represented the sounds of the letters c, d, f, g, k, l, n, s, t, th, v, y, and z.

C. The mouth was open. This mouth was open halfway between the B mouth and the D mouth. This represented vowels sounds such as i (peel), ɪ (pity), and ә (upon).

D. The mouth was wide open. This represented vowels such as e (pay), ɛ (pet), and ɑ (father).

E. This mouth was halfway between the D mouth and the F mouth, open with a slight pucker. It represented an r sound.

F. This mouth puckered. It represented q, w, and the u (pool) sound.

The numbered mouths in the figure are similar to the lettered mouths just given. I’ve added a couple more to show you some other possibilities.

Typical mouths used for animation.

Sound Effects

Anime and other action work can contain many sound effects, as characters run, fall, scream, fight, die, etc. These effects can be some of the hardest sounds to reproduce — grunts, chewing, kissing. Directors may tell you to cover your mouth because this is a covered sound. They’ll tell you that your mouth is too open or too closed. Perhaps the difficulty is partly cultural, as different cultures produce sounds differently.

The Challenges of Anime

Japanese anime was traditionally produced for adults. When anime was brought to the United States for American television, it was adapted here for children, which often caused many problems. The completed episodes would arrive with a Japanese translation into English. Often the material was not at all suitable for kids. There might be too much narration, and much of it would need to be taken out and dialogue added instead. Some things had to be censored out, making the episodes too short. So some of the American production companies that imported anime for American cartoons rewrote and reedited the animated footage, making the stories more suitable for children, but changing them considerably. Footage was taken from other episodes and edited in to make them the right length. Sometimes character names were changed as well. In such cases, actors were not dubbing the original version, but essentially creating new voices within the guidelines of the American production company. Some say that this was more about saving money on Saturday morning cartoons than it was about anything else.

Today there is a growing market for anime for adults, with many series targeted to middle school and high school kids. A few series are targeted to elementary age children. Because the adult market is there, and viewers have complained about story tampering, there is probably less of this repurposing being done. Much of the adult anime is moving and funny, which requires really good acting skills.

The majority of actors working in anime today have a background in theatre. The original Japanese actors have a reputation for good acting skills. Some anime viewers prefer to watch their anime in the original Japanese with subtitles because they prefer the Japanese acting. Of course the actors who are dubbing have a more difficult job, as they must be matching the mouth flaps as well as doing a good job of acting. It’s the acting skills that are most important.

Today most anime is dubbed during the day, but in earlier days anime was dubbed in the evenings or at night, often in someone’s garage recording studio. Not all anime work in the United States is union work, and the pay may be less. Networks in the United States generally buy sixty-five episodes of anime as opposed to thirteen episodes of other series, so there is a lot of work.

Getting Work in Anime

Because anime casting directors are looking for good acting skills, it’s a good idea to include an acting resume along with your demo when you send it to someone who casts for anime. See more about the resume in Chapter 7. As for the demo, be sure that your character clips are long enough that the casting director can listen to your acting ability. Skip the headshot. Skip the impersonations. Remember that anime uses mostly natural voices, not cartoony ones.

Many anime studios get hundreds of resumes and demos coming in each week. Casting directors say that they will listen to the demos, but they have no time for calls, and they’ll get very annoyed if you waste their time. DO NOT CALL. Do not email. If they’re interested in you, they’ll probably let you know in a few days or a few weeks. Do remind them with a postcard that you’re out there, but only once every few months. When they do call to set up an audition, be sure that you go. If you don’t have the time to go then, they probably won’t call again.

In addition to needing good acting skills, anime casting directors also need actors who can lip sync to the picture. They expect actors to be pleasant and enthused. They expect confidence, but not attitude. They want someone who takes direction easily. They want someone who is always on time and preferably fifteen to thirty minutes early.

Auditions may be a little different from the standard voice-over audition once directors know you and your work. It may be unnecessary to do any syncing in your audition. In some cases the director will be looking for voices to match the original performance. In other cases the director doesn’t like the original performance, and he’s looking for something better. As a result, the director may record several actresses and ship the auditions to the client for his decision. Sometimes the client is in the room with the director. The client may not give you the role you recorded, but he may give you another role instead. You may get two or three roles.

After an audition, actors will probably be notified between one day to two weeks later. Anime casting directors do not notify actors who did not get the part. Never turn down a role if you want to be called again. Send a follow-up postcard later, keeping the casting director updated on your career. Always include your contact information on each follow-up. Actor/director Richard Epcar says, “The more versatile you are, the more you’ll work.” Just because you don’t get one role doesn’t mean that you won’t be called later. Persevere.

Getting work in anime may be a matter of who you know. The skills needed are essentially the same ones needed for other dubbing work. This has become such a big business that there is no longer time to train anime actors on the job; you must have good skills in order to get work. Anime director Ellyn Stern says, “The best way for a beginning actor to get experience is to look for non-union work, where the stakes are not so high.”

The Anime Process

The process of dubbing for anime is essentially the same as it is for any other dubbing. It is not necessary to know Japanese, as the scripts are prepared in English, and directors know that they’re not going to find many actors who do know Japanese. There are times when everyone in the studio is volunteering their opinions on how to get a line to fit properly. It may be as simple as saying, “I’m” instead of “I am.” Of course, it’s the director’s job, and he has the final say.

When the actor arrives, he is given a script for his loops and told how many loops he will be doing. Actors first look for their own loops. Generally, they will be working alone — no other actors. In front of the actor will be a music stand and a monitor. Actors will be told to go to the first loop to be recorded. There is no time to prepare. Sometimes the director shows the actor the preceding or following loop, but not always. The three-beep system is usually used in the United States. The sound engineer is able to adjust the timing on the beeps, and if an actor has trouble starting on time, an adjustment with more time between beeps is possible and may help. When there is a long loop of perhaps three sentences, it may be difficult to get all three sentences correct in the same take. It’s possible to break up the sentences so that the take from one sentence can be saved and the other two can be redone. When this happens there will be no warning beeps, you must be able to match what you see and hear through the headphones.

Many times you’ll do your looping in less than the two-hour minimum. Then they’ll start looking for walla, and they may ask you to do some wild lines for other characters. “Make your voice heavier.” “Make it older.” “Make it younger.” So they’ll use up the two hours in that way.

If you are required to sing, a separate music track is provided, so the process is like singing karaoke. You won’t be asked to sing unless you have singing on your demo or you have auditioned for singing in advance.

Budget

Budget is important in any production. The actor who will get the most work is the one who can work the most quickly, as well as do a great job. If you’re tempted to give suggestions, consider whether the suggestions are worth the time it will take to make the changes. Maureen O’Connell knows that the reason she worked so much in Spain was that not only could she do a good job, but she could do it in 33 to 55% under the time that was budgeted.

The Director’s Point of View

Dubbing supervisor Richard Epcar worked on Madagascar, Chicken Run, and El Dorado. Sometimes he was involved in the casting process, and sometimes he wasn’t. In some cases he tried to do a voice match, casting an actor who could duplicate the voice of the original American voice actor. Sometimes the studio abroad preferred to cast a local celebrity in the role, and no effort was made to match the original voice. When he casts abroad, he may go through agents or he may hire directly actors that he has worked successfully with in the past. He was hired for his expertise in dubbing, overseeing the production and making sure that it was in sync and the performances were good. He acted as a liaison between the recording session abroad and the producing studio in the United States. Often he would supervise the mix as well. Recording had to be done very quickly. In terms of casting, Epcar says, “The people that come in and do a good job and deliver the goods right off the bat are the ones you’re going to pay attention to.” There was just no time to train newcomers.

Jacques Barreau has spent years traveling around the world casting Warner Bros. Animated product. He likes to break voice characterization into the two areas of voice placement (where the voice can be placed and the sounds available in each area) and voice effect (the way of working with the nose, mouth, and throat). Jacque wants his actors to first place their voice in an area as close as possible to the character they are dubbing. After the voice is placed correctly, then the actor can concentrate on attitude and good acting. Projection techniques and microphone techniques help mimic specific voices as well. Projection is the force of the voice coming out of the mouth (not necessarily the volume). More projection produces more energy. Less projection produces a quieter and calmer effect. Both influence attitude. Being closer to the microphone helps make a voice more sexy or it helps make it bigger and fuller. Farther from the microphone gives a thinner sound.

Cultural differences affect the way that dubbing is done from country to country. There will be different ways of working and different goals in the east and in the west and from one nation to another. In eastern countries the tradition of saving face may mean that a director will ask politely for a “different version” of a take he doesn’t like. Expectations may be different. As of this writing, it is often less important to many Japanese dubbing directors to sync the sound track as exactly as it usually is in the West. However, Japanese voice actors are highly respected for their excellent acting ability and may outperform some of their Western counterparts. Actors do not necessarily have the same training worldwide or even from one generation to another. Neither do directors. This will also affect the way that directors will direct an actor, and it will affect expectations for the final outcome.

In order to do his job as well as he can, the director needs as much information as possible from the originating company. Ideally, he needs scripts with good adaptations (often done where the dubbing is done). Writer’s bibles, character designs, and storyboards all help make the director’s job easier. The director needs ALL the information: when the job must be complete, what order the actors must be recorded (if that is important), and what casting requirements the original directors and company have in mind. Do they expect the same voice placement, texture, energy level, etc? Do they want a local celebrity? One director said that sometimes she has been given only an age range and a one-line description of the character. The more information given to the director and actor, the better the finished job will be.

Advice from Other Actors

JC O’Connell learned dubbing from her sister Maureen. She advises actors to work at dubbing as often as possible to increase their skills or to practice as well as they can at home. She is a singer. She is constantly learning new operas so she sings along with a recording, playing it over and over again to learn the arias. This is a very similar process to dubbing. You’re trying to match someone else’s voice while you’re singing. It involves getting the right rhythms and pitches and counting out the timing. JC says, “(Dubbing) really is watching the lips. You better have a good understanding of plosives. What are labials? When are your lips together? When are they apart?” JC’s advice to actors is “Constantly work on developing your voice through singing, through listening to dialects and foreign languages …. Explore what your voice can do.”

Wrapping Up

Usually, this is no-stress employment. There is no preparation. The sessions require focus, but they usually go pretty smoothly. In the United States, many looping sessions are covered by the Screen Actor’s Guild so there are health and retirement benefits. The pay is less than that of the more glamorous voice-over jobs, but sessions may last only a few hours. No residuals may be paid, however.

There is more advice about the recording session in general in Chapter 9: what to do before the session, what to bring, and some dos and don’ts. Of course the most important advice is to have fun!

Exercises

1. If you already speak more than one language, check around to see if your skills might help you get dubbing work in your area. Make lists of companies who might need your skills and market yourself.

2. Become more fluent in the languages you know.

3. Rent a foreign language version of a film that you’ve watched previously. Note how the dubbed version is synchronized. Pay attention to the quality of the acting.

4. Record a cartoon program on your DVR. Make a rough translation of one scene into the second language you know. Turn off the sound, replay the scene, and, using your translation, practice dubbing. If you need to rewrite your translation to synchronize, do it.

5. If you can find anime or a cartoon in more than one language, buy it in both. Transcribe the adaptation and use it as a script to practice.