THREE

![]()

Expand Your Understanding of Others and Assess Organizational Readiness

Invite people into your life who don’t look like you, don’t think like you, don’t act like you, don’t come from where you come from, and you might find that they will challenge your assumptions and make you grow as a person.

MELLODY HOBSON1

The work to get ready for bold, inclusive conversations is personal, and it also requires assessing organizational readiness. Chapter 2 focused on the self-understanding aspect of readiness. This chapter highlights the importance of learning about other cultures as well as assessing organizational readiness.

In her 2014 TED Talk, “Color Blind or Color Brave?” Mellody Hobson, president of Ariel Capital, challenges us to venture outside our comfort zones, be intentional in engaging with our “others,” and leverage difference, not only for the greater good but also for maximum business impact. Let’s explore why having a greater understanding of other cultures or being “color brave” is so critical to engaging in bold, inclusive conversations.

CHALLENGE SINGLE STORIES

Historically we have not had much practice interacting across difference. In some cases, there were legal restrictions that prohibited cross-cultural interactions. For example, segregation laws kept black and white people from intermingling. Likewise, members of the LGBTQ community were forced to suppress that aspect of their identity until the last several decades. Historically, our norm has been not to express political views, and many of us were taught that religious beliefs that differed from our own were “wrong.”

Readiness requires a level of knowledge about differences that goes beyond your worldview. It means that you have done some study on the issues, you have listened to different perspectives, even those contrary to your own, to give you a more balanced view. As mentioned in Chapter 1, social media gives us the ability to broaden and diversify our networks. However, we typically connect only with those who are most like us. Learning to engage in meaningful dialogue across difference requires not only understanding your view but also understanding what others believe and why. This is sometimes referred to as being able to walk in another’s shoes, or empathy.

Many of us have only a single story about those who are different from us, as discussed in Chapter 2. We lack a wider worldview than what we get from those closest to us. We may be fearful of learning more because we have been taught not to talk about race, politics, and other issues, especially in the workplace. The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) included several questions on its 2013 American Values Survey designed to gauge the range and diversity of Americans’ social networks. The survey results include the following:

![]() Seventy-five percent of white Americans reported that the circle of people with whom they “discuss important matters” is entirely white and only 15 percent said they have a racially mixed social network. Political affiliation made no difference in the results.

Seventy-five percent of white Americans reported that the circle of people with whom they “discuss important matters” is entirely white and only 15 percent said they have a racially mixed social network. Political affiliation made no difference in the results.

![]() Eighty-one percent of white Republicans and 78 percent of white Democrats have social networks that are entirely composed of whites. Among white independents, 73 percent say their social networks are comprised entirely of people who are white.

Eighty-one percent of white Republicans and 78 percent of white Democrats have social networks that are entirely composed of whites. Among white independents, 73 percent say their social networks are comprised entirely of people who are white.

![]() Almost two-thirds (65 percent) of black Americans report having a social network comprised only of black people. However, 23 percent of black Americans answered that their network includes a mix of people from other racial and ethnic backgrounds, a percentage somewhat higher than that of white Americans.

Almost two-thirds (65 percent) of black Americans report having a social network comprised only of black people. However, 23 percent of black Americans answered that their network includes a mix of people from other racial and ethnic backgrounds, a percentage somewhat higher than that of white Americans.

![]() In contrast, only 46 percent of Hispanics report that their social networks are limited only to other Hispanics, and 34 percent report having a mixed social network.

In contrast, only 46 percent of Hispanics report that their social networks are limited only to other Hispanics, and 34 percent report having a mixed social network.

![]() There were no gender differences and only slight differences by age. White Americans aged 65 and older were only slightly more likely than white young adults (ages 18–29) to have entirely white social networks (80 percent vs. 72 percent).2

There were no gender differences and only slight differences by age. White Americans aged 65 and older were only slightly more likely than white young adults (ages 18–29) to have entirely white social networks (80 percent vs. 72 percent).2

In another survey, 56 percent of Americans think that Muslim values are at odds with American values. When asked, however, how often they have talked with a Muslim in the past year, 68 percent said never or seldom.3 We certainly can’t have meaningful dialogue across differences if we are not having any cross-difference contact at all.

The idea of integrating our schools and our neighborhoods is based on the premise that there are advantages to cross-cultural interactions. If we get to know each other better through more exposure and experience with each other, we break down the barriers and can more effectively explore our similarities and differences. As a matter of fact, George Romney, Mitt Romney’s father, was a passionate supporter of integrated housing in the ’60s. He said, “We’ve got to put an end to the idea of moving to suburban areas and living only among people of the same economic and social class.”4 Needless to say, that was not a popular worldview at the time, nor is it today.

PRACTICE THE 4Es

A critical aspect of being ready to have bold conversations about polarizing subjects is to have some knowledge of those who come from a different cultural community than your own. For this to happen, I offer the 4Es—Exposure, Experience, Education, and Empathy.

1. Exposure

An impactful exercise called Who’s in My World invites participants to consider their own identity and the identity of those with whom they most often associate. For example, if I identify as black, and most of the people in my world are also black (e.g., people who regularly visit my home, people I socialize with, people in the movies I see and books that I read, my close friends, people in my faith community), I am getting very little opportunity for exposure to difference. If we don’t have cross-group exposure, the likelihood of expanding our understanding of others is limited. Who’s in your world?

2. Experience

Experience with difference is not the same as exposure. Diversity can be all around you without you ever really creating meaningful relationships and mutual understanding. Experience is about engaging with those who are different from you in ways that are cross-culturally enriching. Forging such relationships means that you are willing to address your fears, be vulnerable, and shed single-story narratives.

AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson’s story about his lack of knowledge of his black friend’s life experience discussed in Chapter 1 is a poignant example of how we can have exposure to difference without a meaningful experience. Developing cross-cultural relationships takes time, energy, and desire.

It may be more difficult for employees who think they have little in common to develop meaningful relationships. For instance, let’s say the manager is a white male and the employee is a Southeast Asian woman. Finding commonalities to begin to connect and develop a meaningful work relationship that demonstrates that the manager cares about her as a person—and not just a production unit—may not be easy for either party. However, it is critical to engagement and retention, and vital in preparing for bold, inclusive conversations. Sharing meaningful experiences might include external team-building events, a work book club that allows different perspectives on the content, time in team meetings for members to talk about their culture.

One of the key drivers of engagement, according to Gallup’s Q12 Engagement Survey is “somebody cares about me at work.”5 Gallup further asserts that it is important for employees to have a sense of belonging, which means feeling included. A study conducted by the Center for Talent Innovation, “Vaulting the Color Bar: How Sponsorship Levers Multicultural Professionals into Leadership,” showed that 40 percent of African Americans and one-third of people of color overall feel like “outsiders” in their corporate culture, versus 26 percent of white employees who feel that way.6 Bold, inclusive conversations will only be successful if employees feel that they belong, that they are cared about, and that their voices will be heard.

Encourage Reciprocal Learning

If you didn’t grow up like I did then you don’t know, and if you don’t know it’s probably better you don’t judge.

Junot Díaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao7

The need to expand our knowledge about the other is mutual. The Winters Group offers a program called Cross-cultural Learning Partners, which aims to foster reciprocal learning. We pair individuals who are different in some way (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, religion) and invite them to go on a guided journey of learning about each other. This includes short lessons with reflective questions and recommendations for experiences that they can share (e.g., engage with each other’s faith community or visit a cultural museum together).

The Cross-cultural Learning Partners program is grounded in the reciprocal nature of the learning, unlike many one-way mentoring programs, such as reverse mentoring, a very popular concept in today’s workplace. Reverse mentoring programs are designed so that the person who is a member of the dominant group identity can learn more about the individual who is part of the non-dominant group. One-way programs perpetuate an “us-and-them” environment, and can contribute to polarization. Cross-cultural learning is specifically designed so that both parties are learning from each other, reducing the feeling that it is one-sided.

Historically marginalized groups need to learn about the majority as much as the majority needs to learn about marginalized groups. However, I contend that the historically marginalized groups may have a head start on this journey because our exposure, experience, and education has largely been from the dominant group perspective.

3. Education

Enhancing your exposure and experience is part of your education. However, those two Es need to be augmented with more formal education around difference. This can happen via workplace training, advanced university courses, movies, documentaries, museum visits, books, travel, and so on.

Beware of media reports as the only source of education about difference. We know that most reporting is biased, but beyond that, it may not provide a contextual understanding of the facts.

The Center for Racial Justice Innovation (Race Forward), compiled a report in 2015 called the Race Reporting Guide.8 Geared toward helping journalists, the guide asserts that most race reporting focuses on individual, specific incidents or events and fails to include a broader context, such as the role of history, institutional policies, and inequitable practices; and it rarely features much coverage of racial justice advocacy or solutions. The report calls for a more systemic analysis that looks at root causes and the mechanisms that feed into patterns.9

The report also asserts that language matters. The words we use can be triggers (see Chapter 7 for examples of triggers) or paint stereotypical pictures. For example, terms like “illegal immigrants” should not be used. “Illegal” should be used to describe an action and not the person. Understanding both the role of language and the significance of educating oneself on broader contexts are critical to preparing for bold, inclusive conversations.

Let’s Stop Punishing

There is a tendency to want to punish people, especially public figures, when they say something that offends a particular group. This results in a lot of media coverage and calls for their resignations, or worse; and when the action is taken against this obviously “bad” person (racist/sexist/homophobic, etc.), we all feel better again. But, what have we learned?

For those who may understand the reasons why the comments were inappropriate or offensive, the punishment is often warranted. For those who may not understand the context, it may have the effect of shutting down the possibility of conversations on polarizing topics. The fear of offending or not knowing enough can loom large in these situations, and unless people are inclined to dig deeper and do their own learning, they may alienate themselves from that group.

Juan Williams, a black journalist, was fired from NPR in 2010 when he said in an interview with Bill O’Reilly, “When I get on the plane, I got to tell you, if I see people who are in Muslim garb and I think, you know, they are identifying themselves first and foremost as Muslims, I get worried. I get nervous.”10

Granted, as a public figure he probably should not have said that. However, he was probably articulating what a lot of Americans think (survey research would confirm that this is the case), and he was being honest. This could have been viewed as an opportunity to have deeper dialogue, to understand the underlying context with which the comments were made. It was an opportunity for education that was missed. If people think they will be punished for sharing honest fears and concerns, they will certainly not want to do so.

In a training session that I facilitated many years ago, a gentleman came up to me at the conclusion and said, “I got it . . . I just won’t talk to any of my black coworkers. I don’t want to offend anybody, and it is just better for me to keep my mouth shut.” He obviously did not want to do the personal work required to learn more about differences.

There are certainly boundaries. There are certain comments or actions that deserve consequences (i.e., punishment). Many organizations have zero-tolerance rules that are explicitly spelled out in their Human Resources policies. I am not talking about those obvious, egregious comments that are mostly known to employees (e.g., racist, sexist, homophobic jokes; the “n” word). I mean the type of remarks that come from the I-don’t-know-what-I-don’t-know place on the learning curve. For example, it might be offensive if someone asks a black woman, “How did you get your hair like that?” or “May I touch your hair?” Rather than take offense, the black woman can use it as a learning opportunity to share with the person why such questions are offensive and inappropriate. If she assumes positive intent, the conversation is very different from the one that might have happened otherwise.

As I said earlier, we must cut each other some slack for bold, inclusive conversations to occur.

Ask yourself:

![]() Do I know the history of the other group from their perspective?

Do I know the history of the other group from their perspective?

![]() Do I understand the underlying systems that impact outcomes for the group(s)?

Do I understand the underlying systems that impact outcomes for the group(s)?

![]() What do I know in general about cultural differences? (e.g., direct vs. indirect communication styles, individualistic vs. group-oriented cultures, how power is displayed, etc.)

What do I know in general about cultural differences? (e.g., direct vs. indirect communication styles, individualistic vs. group-oriented cultures, how power is displayed, etc.)

![]() What do I know about their values and beliefs and how and why they were shaped as they are? (e.g., millennials’ experience with technology differs from that of baby boomers, which shapes their worldview)

What do I know about their values and beliefs and how and why they were shaped as they are? (e.g., millennials’ experience with technology differs from that of baby boomers, which shapes their worldview)

4. Empathy

Effective dialogue across difference will not happen if we cannot be empathetic. Empathy is not sympathy. Sympathy engenders pity. Empathy leads to mutual understanding and respect. It is encompassed in the theories of emotional intelligence, a concept that is now understood to drive personal and business success. Emotional intelligence is comprised of four parts: self-awareness, self-management, other awareness, and managing relationships. Emotional intelligence is a vital ingredient for effective bold, inclusive conversations.

Recognize Culturally Learned Communication Styles

While there are many cross-cultural differences that have been well researched and documented, the one that is most important to understand when having bold, inclusive conversations is how we have learned to communicate and handle conflict.

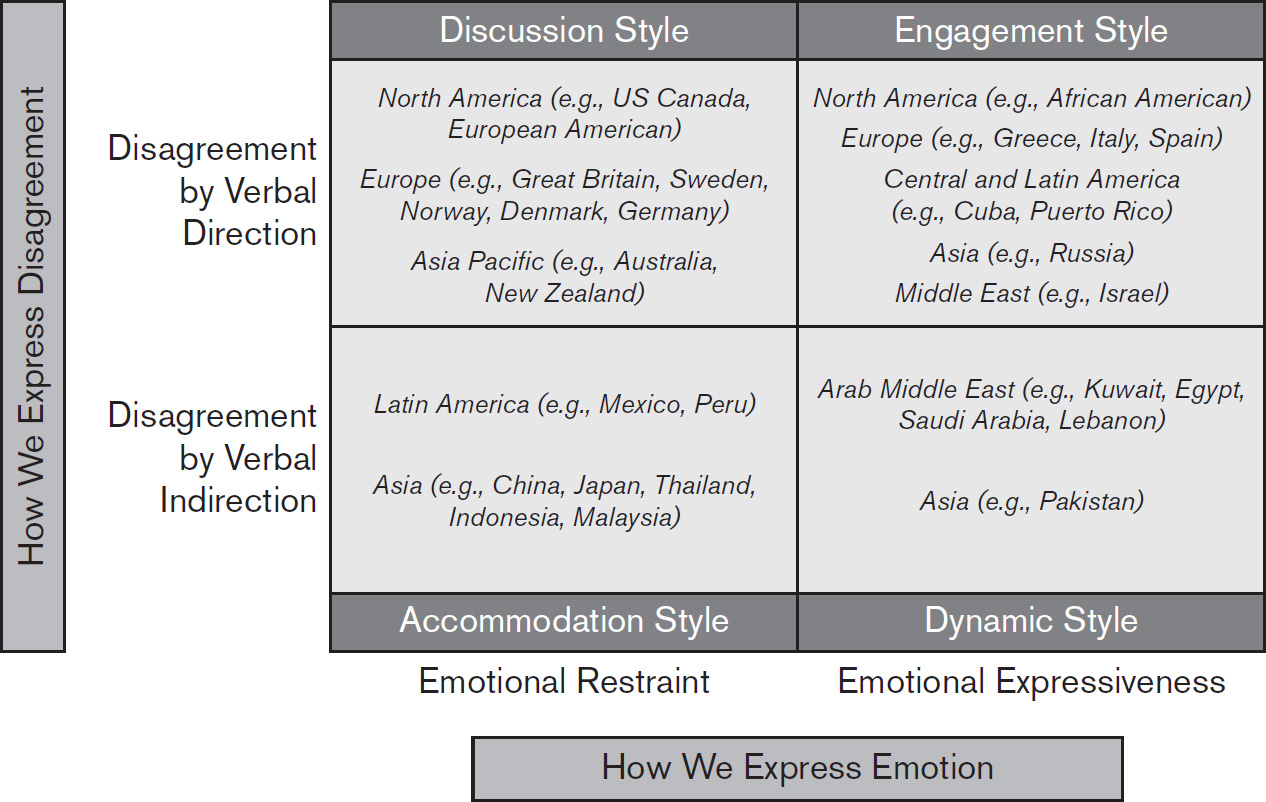

The Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory, developed by Dr. Mitchell Hammer, helps us to distinguish cultural preferences for solving problems and handling conflict. There are four preferred styles: discussion, engagement, accommodation, and dynamic, as shown below in Figure 4.

Discussion style is most preferred by Euro-American, Northern European, and Canadian cultures. It is characterized as direct and emotionally controlled. Engagement style is most commonly found among African Americans, Greeks, some Western Europeans, and some Latino cultures. Engagement style is direct and emotionally expressive. Accommodation style, preferred by many Asian cultures, is indirect and emotionally restrained. Dynamic style, common among Middle Eastern cultures, is indirect and emotionally expressive.

Those who prefer discussion style will advocate for logical, rational, fact-based arguments with limited emotional expressiveness, while those whose style is either dynamic or engagement-oriented will be comfortable with a strong display of emotion; they may be more apt to tell stories or use metaphors and circular reasoning. Someone who is prone to discussion style will use a more linear approach. Likely to prefer that people speak one at a time, discussion-style leaders may go around the room in a team meeting, asking everyone to speak in turn. Engagement-style leaders, on the other hand, may be more comfortable with over-talking and being interrupted.

FIGURE 4. INTERCULTURAL CONFLICT STYLES

(based on the Intercultural Conflict Style Model, M.R. Hammer, 2009)

I have coached several African American leaders who have received feedback that their passion (translation: display of emotion) needs to be contained. In one situation, the young woman was the highest ranking African American in the company. She was on the fast track. She developed a presentation about a very mundane compliance issue and decided to be creative in how she presented it. Rather than just sharing the facts, she developed a story about the topic using fictional characters.

After the presentation, she was under the impression that it had gone very well. However, a few days later, her manager shared that several of the senior leaders thought she should have just stayed with the facts. Her approach was inappropriate for the topic. At times, they said they thought they were listening to a Baptist preacher. This young woman’s father, in fact, was a Baptist preacher and she acknowledged that unconsciously she may have mimicked some of his style. However, she was still hurt and frustrated because she felt even more alienated by her difference.

The Euro-American communication style relies heavily on logic and technical information rather than illusion, metaphor, and more creative and emotional styles of persuasion. Learning to communicate across cultures is a shared responsibility. In this case, if both had known more about culturally learned communication styles, the outcome may have been different.

Direct-communication cultures tend to be okay with voicing their unfiltered opinions and shooting from the hip, as the saying goes. Indirect cultures may be very uncomfortable speaking up without having had some reflection time or speaking before a senior leader has spoken. Disagreeing with one’s superior might be considered disrespectful in some Asian cultures, whereas in discussion or engagement cultures, healthy debate is expected. Indirect cultures may not want criticism in public, whereas direct culture may be fine with public constructive feedback.

I have heard numerous times from Euro-American leaders that their Asian employees tend not to speak up in meetings. Often their solution is to force everyone to speak via round-robin techniques. This approach may be very uncomfortable for some Asian employees and those from other indirect cultures. When employees are reticent about speaking up in a meeting, discussion- or engagement-style leaders may interpret that they are not conversant on the topic or they are disengaged.

Using the concepts of the DNA model outlined in Chapter 2, consider alternate interpretations for the behavior. One alternate interpretation is that these employees have a different cultural norm for engaging. The solution might be to expand the number of approaches for soliciting input (e.g., one-one or electronic forms of communication) and not making it mandatory that everyone speak during a group meeting.

In a study conducted by Sylvia Ann Hewlett and reported in the Harvard Business Review, employees in a “speak-up” culture are 3.5 times as likely to contribute their full innovative potential.11 However, we should consider alternative interpretations of what “speak up” means from a cultural perspective. It is critical, as part of your readiness for bold, inclusive conversations, to have a basic understanding of culturally learned communication styles.

A cautionary note: I do not want to stereotype different groups. Not all African Americans communicate engagement style; nor do all Asians prefer accommodation style. The explanation of the different styles is meant to help us understand that there are meaningful differences in how cultures communicate based on their norms, values, and beliefs. However, it does not mean that everyone who is a member of that group shares that characteristic. Some cultural groups, such as Native Americans, or Africans, may fall into any of the four styles, depending on factors including their history in terms of mobility and colonization.

BUILD CROSS-CULTURAL TRUST

There are myriad reasons for a lack of cross-cultural trust. Many historically marginalized groups have been taught not to trust the “other” based on historical atrocities, accounts of which have been passed down from generation to generation. “Never trust the white man” was a common admonition in my household growing up. I was also taught not to trust or associate with anybody who practiced a religion different from my own because they were surely going to hell. And according to my mother, Jewish people could not be trusted to be honest. How many of us come to the workplace with embedded “records” that may now be deep in our unconscious minds but nonetheless drive our perceptions and behaviors?

We don’t have to rely on history to understand the lack of trust between majority and minority groups. There are numerous modern-day examples of why trust is limited. African American communities may not trust police because of their firsthand experiences with racial profiling. Women may not trust leadership to provide equal benefits and pay.

By the same token, majority-group members may not trust historically marginalized groups because they don’t know them very well or because of the single-story phenomenon mentioned earlier that perpetuates stereotypes, such as a low intelligence, lack of motivation (e.g., blacks are lazy), and dishonesty (e.g., you can’t trust Arabs).

One of the key readiness steps before embarking on bold, inclusive conversations is building trust. People will not talk honestly and openly when there is little or no trust. To build trust you need to consistently practice the 4Es as outlined above. Trust cannot be built without exposure to and experience with those who are different from you. How will you know when there is trust between two people or among the team? One key sign is the extent to which there is an openness to revealing and sharing personal information. Another sign of a trusting relationship is the willingness to be vulnerable—admitting weaknesses, acknowledging what you don’t know.

Paul Zak’s Harvard Business Review article, “The Neuroscience of Trust,” explores a study that compared people at low-trust companies with people at high-trust companies. Those at high-trust companies report 74 percent less stress, 106 percent more energy at work, 50 percent higher productivity, 13 percent fewer sick days, 76 percent more engagement, 29 percent more satisfaction with their lives, and 40 percent less burnout.12 He and his colleagues found through scientific brain studies and other research that there are eight management behaviors that foster trust. Four are particularly pertinent to fostering bold, inclusive conversations.

Share Information Broadly: If you do not have the whole picture (e.g., just a single story), it is impossible to have effective dialogue.

Intentionally Build Relationships: As mentioned above, exposure and experience with differences are critical components of bold, inclusive conversations. The better I know you, the more I can trust you. We tend not to develop relationships across race, ethnicity, disability status, sexual orientation in part due to the fear of the unknown and our human tendency to stay with our own tribe. Zak’s research shows that when people intentionally build social ties at work, their performance improved. Finding common ground, as recommended in Chapter 2, can facilitate the ability to begin to build meaningful relationships across difference.

Show Vulnerability: The willingness on the part of leaders to admit when they do not know something builds credibility and trust, according to Zak’s research. It may be more difficult to admit ignorance on topics like race and religion due to the fear of how it will look to the employee. Managers may feel as if they should know more than they do, and historically marginalized employees may feel the same. This is where patience and cutting each other some slack are important. When a manager genuinely shows interest and honestly admits to not knowing, it will likely engender more trust.

Facilitate Whole-Person Growth: We often define inclusion, in part, as the ability for individuals to bring their whole selves to work. Zak contends that assessing personal growth with discussions about work-life integration and family has a powerful effect on trust, as does allowing time for recreation and reflection, which improves engagement and retention. Leaders need to build skills to be comfortable talking about personal aspects with employees who are culturally different from them. I often hear from historically marginalized groups that such conversations are awkward. There is a shared responsibility. Members of historically marginalized groups need to develop skills for the more personal conversations as well. Finding common ground, discussed in Chapter 2, is a good place to start.

In Steven Covey’s book, Speed of Trust, one of the core tenets of building trusting relationships is straight talk.13 “Say what is on your mind. Don’t hide your agenda. When we talk straight, we tell the truth and leave the right impression.” While this may be sound advice, it doesn’t work all of the time if you are from a historically marginalized group. Here are some reasons why straight talk is not always safe.

From the perspective of the historically marginalized group:

![]() “If I tell you exactly what it feels like to be a ____ in this organization, you think I am whining or being overly sensitive.”

“If I tell you exactly what it feels like to be a ____ in this organization, you think I am whining or being overly sensitive.”

![]() “Straight talk will make you feel guilty or ashamed, and I don’t want to make you feel bad. It could be a career derailer.”

“Straight talk will make you feel guilty or ashamed, and I don’t want to make you feel bad. It could be a career derailer.”

![]() “I don’t trust you with my straight talk. You would just not understand it, and I am not sure how you might share it or misinterpret it.”

“I don’t trust you with my straight talk. You would just not understand it, and I am not sure how you might share it or misinterpret it.”

![]() “If I say what is on my mind, I might lose my job.”

“If I say what is on my mind, I might lose my job.”

![]() “Nobody in this company really says what they think. I am not going to put myself out there.”

“Nobody in this company really says what they think. I am not going to put myself out there.”

![]() “I am not the spokesperson for my identity group. You may use my perspective to generalize my group.”

“I am not the spokesperson for my identity group. You may use my perspective to generalize my group.”

From the dominant-group perspective:

![]() “If I was to talk straight to you, I would have to admit that I really don’t know anything about your group. I am embarrassed to admit that.”

“If I was to talk straight to you, I would have to admit that I really don’t know anything about your group. I am embarrassed to admit that.”

![]() “I can’t talk straight with you because you might get offended and file a lawsuit against the company.”

“I can’t talk straight with you because you might get offended and file a lawsuit against the company.”

![]() “Nobody in this company really says what they think. I am not going to put myself out there.”

“Nobody in this company really says what they think. I am not going to put myself out there.”

Trust is built differently across cultures. Thomas Koch-man in Conflict Styles in Black and White posited that African Americans tend to build trust via sharing one’s emotional reality in a direct manner and whites tend to build trust via controlling emotion.14 He found that black people can trust you if you are straight with them and tell them exactly what you think and feel. He found that for whites, trust was built when you spare feelings to help keep the difficult conversation “on track.”

Such differences need to be acknowledged and understood to build mutual trust across difference. Experts agree that it takes years to build trust, seconds to break it, and forever to repair it. Building trust is a process—a journey—and not an event.

IS IT FACT OR TR UTH?

There’s a world of difference between truth and facts. Facts can obscure the truth.

Maya Angelou15

Understanding the difference between fact and truth can help us to build trust. While it might seem like splitting hairs, I think it is important to call out the distinction. Some will say, “just the facts please.” Others will say, “What is the truth about this situation?” A fact is something that is undeniable and will stand until proven wrong. It is universally accepted. It is something that has happened or occurred. For example, that the Louvre is in Paris is a fact. Truth is much more subjective, incorporating feelings and beliefs, and it can change. Something may be true for me—I am afraid of heights—but not true for you. Additionally I might not always be afraid of heights. It may be true now but not always.

The reason that this is an important distinction is because in dialogue we can erode trust if we judge one’s truth. “It’s silly to be afraid of heights” or “You need to get over that” would be judgments that could negatively impact conversation. One’s perception of a situation is one’s truth. Respecting another’s truth is important. Understanding why something is true for that individual is necessary to engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

For example, if a woman thinks that she is not being taken seriously for her contributions, this might be considered her truth. This is what she experiences. She may have facts to substantiate her beliefs: incidences that have occurred—someone else got the promotion, for example. Her male boss thinks otherwise, based on his truth. The fact might be that over his career he has promoted a number of women. It does not change this woman’s truth that she has not been promoted. It can be challenging to find common ground without sorting out the facts from one’s truth and recognizing that they are both important.

SEPARATE THE PERSON FROM THE POSITION

President Barack Obama said we can disagree without being disagreeable. We can also oppose someone’s perspective and not demonize that person. For example, we may read a post from a friend or colleague on Facebook about their political leanings with which we disagree, and we immediately judge the person rather than just judging the idea. When we agree with others, we judge them as intelligent and informed. However, when we disagree, our judgments of the person are negative. We may label them as racists or homophobic, based on their support of a particular candidate or position.

Developing the capability to judge one’s idea without judging the person with that belief is really hard. During the 2016 presidential campaign there was a tendency by some Democrats to judge all Donald Trump supporters as bigots. Without knowing why someone supported one candidate or another, we cannot make broad judgments about their principles.

Be cautious about being too eager to be inclusive for the sake of inclusion. Sometimes there is a thin line between being inclusive of diverse versus harmful positions. The goal should not be to accept all positions, rather to be initially curious and open to understanding why one may take a particular position before totally judging the person.

As another example, pro-choice versus pro-life perspectives are very polarizing in this country. If you are pro-choice, can you respect a person who is pro-life? Can you disagree with someone’s position without negatively labeling the person? If the person holding the pro-life viewpoint takes some action that is harmful to others (e.g., attempting to stop individuals from entering abortion clinics), you would have grounds for judging the person based on potentially harmful behavior and their refusal to allow others to exercise their rights. If, however, the person with the pro-life views exercises their beliefs as it relates to their own decisions and choices, and respects that others have the right to make different decisions and choices, perhaps we are then able to separate the person from the position.

ASSESS ORGANIZATIONAL READINESS

The notion of culture certainly extends to organizational culture. So far, I have advised you to enhance your understanding of your own cultural norms and frameworks as well as those of others. Understanding the organizational culture is also key in assessing readiness to engage in bold, inclusive conversations. How would you answer the following questions about your organization?

![]() Is inclusion explicitly articulated as one of the organization’s values?

Is inclusion explicitly articulated as one of the organization’s values?

![]() Does the organization demonstrate that it values inclusion through actions by all leaders in the organization?

Does the organization demonstrate that it values inclusion through actions by all leaders in the organization?

![]() Are there formal programs in place promoting inclusion (e.g., employee network groups, mentoring, training, recruitment of diverse talent, etc.)?

Are there formal programs in place promoting inclusion (e.g., employee network groups, mentoring, training, recruitment of diverse talent, etc.)?

![]() Does the organization celebrate diversity with different company-sponsored events?

Does the organization celebrate diversity with different company-sponsored events?

![]() Does the organization actively support philanthropic causes of diverse groups?

Does the organization actively support philanthropic causes of diverse groups?

![]() Is there visible evidence of employee diversity?

Is there visible evidence of employee diversity?

![]() Are leaders evaluated on their inclusion practices?

Are leaders evaluated on their inclusion practices?

![]() Is it a culture of risk taking or risk aversion?

Is it a culture of risk taking or risk aversion?

![]() Is it common to call out the “elephants in the room” or does the organization tend not to tackle tough subjects?

Is it common to call out the “elephants in the room” or does the organization tend not to tackle tough subjects?

![]() Would you characterize the culture as passive-aggressive?

Would you characterize the culture as passive-aggressive?

![]() Do leaders show they care about all employees?

Do leaders show they care about all employees?

![]() Is the culture open or closed (i.e., few people allowed in the inner circle)?

Is the culture open or closed (i.e., few people allowed in the inner circle)?

![]() Are leaders well trained to support employee development and address relevant personal concerns?

Are leaders well trained to support employee development and address relevant personal concerns?

![]() What is the level of trust of leadership?

What is the level of trust of leadership?

If the culture does not demonstrate that it values all employees and incorporates inclusion as one of its core values, it may not be ready to tackle bold, inclusive conversations.

As part of the readiness process, one organization assembled a small task force to evaluate the content of the dialogue session against the organizational culture. The initial content was designed to focus primarily on issues of race. The team determined that while race needed to be addressed as its own issue, the organization was not ready to tackle race by itself. This initial session would be more successful, they concluded, if it was reframed to encompass other diversity dimensions. The title was changed from Workplace Trauma in the age of #BlackLivesMatter to Affirming Inclusion and Building Bridges during Challenging Times. Piloted with a group of HR and diversity leaders, the session was very successful, and the organization now plans to continue the dialogues, working up to discussing race, as well as a more comprehensive treatment of specific topics, such as LGBTQ and religion.

You may think that you are personally ready to have bold conversations on polarizing topics, and you may also think that your organization needs to engage in these conversations because it would help to create a more inclusive climate. However, the facts may suggest otherwise. Tackling these topics before the organization is ready could be disastrous, leaving those involved feeling more alienated and polarized. In Chapter 2, I introduced the Intercultural Development Inventory and the Intercultural Developmental Continuum, which reveals that most people have a minimization mindset. A bold discussion on race will likely be more successful with those who are at acceptance and adaptation on the continuum.

A session that is inclusive of different dimensions of diversity works well for those with a minimization worldview because they may view it as “treating everyone the same” and not focusing on one particular group. It was a smart move for this organization to recognize that it needed more development—both in self-understanding and in understanding other cultures—before delving into race, one of the most complex and divisive issues of our time.

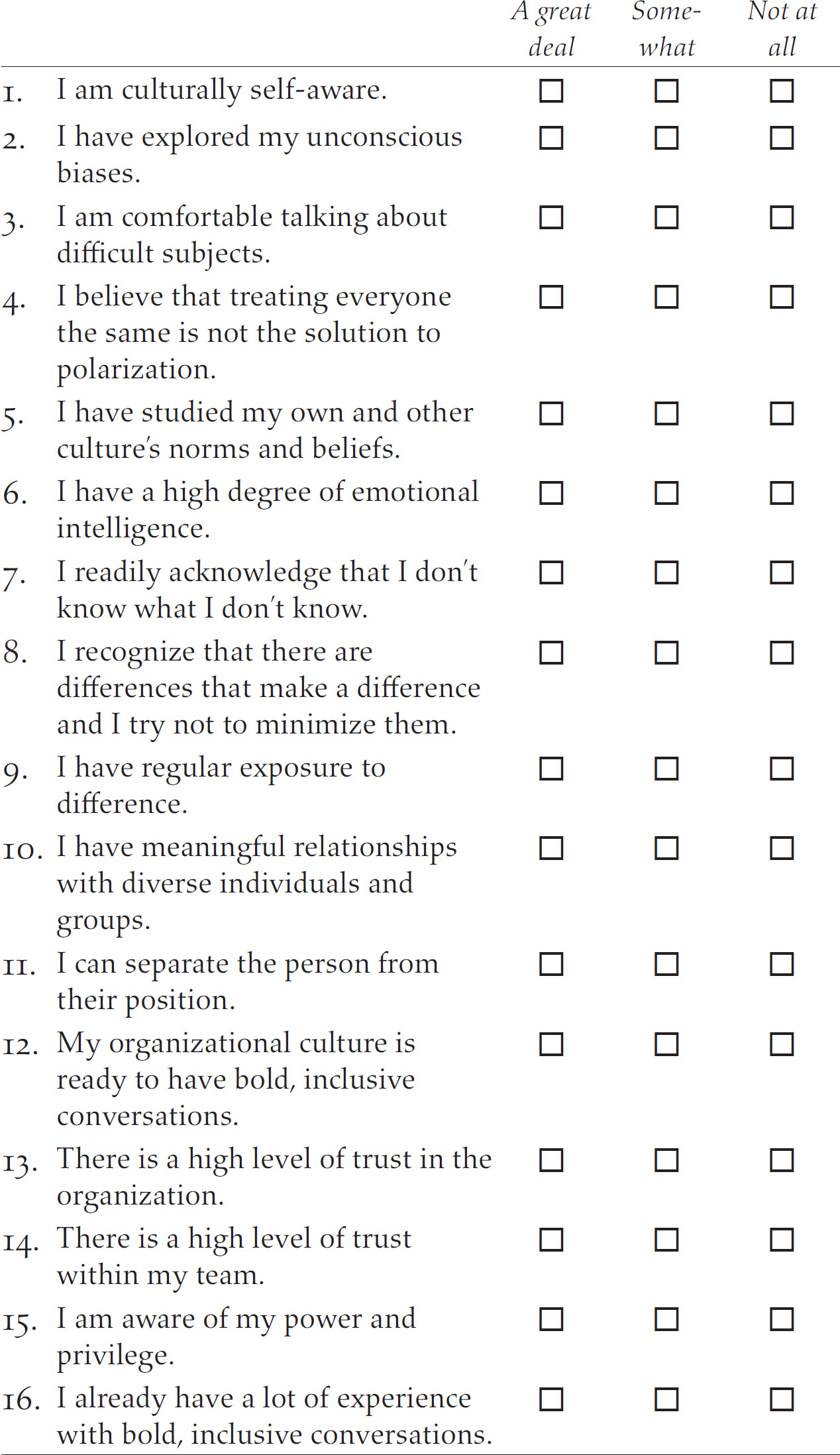

ARE YOU REALLY READY FOR BOLD, INCLUSIVE CONVERSATIONS?

After reading Chapters 2 and 3, you might be thinking, If I have to do all of this to get ready to have a bold, inclusive conversation, forget it. It is just too much work.

Do not despair. If you have gotten through these chapters, you must have some level of interest in learning how to engage in bold conversations.

Chapters 2 and 3 simply highlight the imperative of ensuring that you are ready to engage in these difficult cross-cultural discussions and some of the important knowledge about others that is necessary. Readiness is a journey. You do not have to wait until you have mastered all of the readiness skills before you start to have conversations across difference.

At the very least, raise your self-awareness and your knowledge of the differences, as outlined in these two chapters, before attempting to engage in bold, inclusive conversations. You will need to acknowledge your skill level (e.g., “I am new at this,” “I don’t know as much as I need to know about our differences,” “I am still learning and hope you will support me in that journey”). As proven by Zak’s research highlighted above, showing your vulnerability and being willing to learn can go a long way in building trusting relationships.

Answer the self-assessment survey on page 64 to gauge your readiness for bold, inclusive conversations.

If you answered “somewhat” or “not at all” to all of the statements, you are definitely not ready to engage in polarizing conversations. If you answered “somewhat” or “not at all” to more than half of the statements, proceed with caution. If you were able to answer “a great deal” or “somewhat” to at least half of the statements, you can likely move more quickly through the steps that will be provided in Chapters 5 and 6.

Simultaneously work on your readiness and move cautiously into the conversations, being mindful of how far your readiness will take you. As this is a skill, do not go beyond your capabilities, and continue to enhance them so that you can enjoy increasingly mutually beneficial interchanges across differences.

You might be thinking, How long will it take to get ready? I really don’t know. As you can see from the self-assessment, it depends on a number of different factors. The key point is, if you are not ready, don’t try to tackle the tough conversations. Go slowly and methodically. The remaining chapters provide guidance on the process.

READINESS SELF-ASSESSMENT

CHAPTER 3 ![]() TIPS FOR TALKING ABOUT IT!

TIPS FOR TALKING ABOUT IT!

![]() Learn about those who are different. We may not have enough knowledge of cultural differences to effectively engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

Learn about those who are different. We may not have enough knowledge of cultural differences to effectively engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

![]() Learn to understand others from their worldview, not yours. Learning about others from their perspective (i.e., the ability to walk in their shoes) is key to forging mutual understanding.

Learn to understand others from their worldview, not yours. Learning about others from their perspective (i.e., the ability to walk in their shoes) is key to forging mutual understanding.

![]() Remember that learning about others requires exposure, experience, education, and empathy.

Remember that learning about others requires exposure, experience, education, and empathy.

![]() Engage in mutual or reciprocal learning. The need to expand our knowledge about the other is mutual.

Engage in mutual or reciprocal learning. The need to expand our knowledge about the other is mutual.

![]() Recognize the importance of trust. Building trust across difference is a prerequisite to bold, inclusive conversations.

Recognize the importance of trust. Building trust across difference is a prerequisite to bold, inclusive conversations.

![]() Learn how cultures differ in their communication styles to engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

Learn how cultures differ in their communication styles to engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

![]() As well as personal readiness, assess organizational readiness for bold, inclusive conversations.

As well as personal readiness, assess organizational readiness for bold, inclusive conversations.