TWO

![]()

Get Yourself Ready for Bold, Inclusive Conversations

Knowing others is intelligence; knowing yourself is true wisdom. Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.

LAOTZU1

Chapter 1 focuses on the compelling business case for learning how to engage in bold, inclusive conversations. This chapter outlines what you need to do to get ready for the conversation. As highlighted in the preface, this is hard work. And the hard work begins with you. In the next chapter, I will delve into the importance of learning about those who are different from you as another key aspect of getting ready—also hard work.

A key reason for not being able to effectively dialogue about polarizing topics is our lack of cultural self-understanding. Bold conversations about race, religion, politics, and other polarizing subjects require different skills than other types of conversations. Historically we have not wanted to talk about these topics because it is just too hard, making us uncomfortable and often eliciting strong emotional responses.

I don’t think we necessarily consider the ability to dialogue about race or other lightning-rod topics as a real skill, or at least not the way the dictionary defines the word as “difficult work.” Our behaviors would suggest that we think we can expect individuals from vastly different world experiences to be able to sit together and discuss controversial and polarizing issues without the readiness and preparation to do so effectively. Getting yourself ready is a developmental process that involves learning to assess your current capabilities, understanding the gap between where you are and where you need to be for meaningful cross-difference dialogue. Readiness can actually take a long time because it is a skill that one develops over time through knowledge acquisition and practice.

The self-readiness steps include

![]() focusing on cultural self-understanding by exploring your cultural identity

focusing on cultural self-understanding by exploring your cultural identity

![]() getting beyond “blindness”

getting beyond “blindness”

![]() facing your fears and biases

facing your fears and biases

![]() acknowledging the power in your power and privilege

acknowledging the power in your power and privilege

EXPLORE YOUR OWN CULTURAL I DENTITY

We as humans must deal with an identity located in the core of the individual yet also in the core of our cultural community.

Erik Erikson, developmental psychologist2

Our cultural identity shapes our worldviews and, thus, all of the different opinions, attitudes, ideologies, and assumptions that we bring into our conversations.

Before you can have a bold conversation, you should engage in deep introspection. Any self-help book or leadership development program advises that the first step toward mastery is self-understanding. Introspection involves thinking about what you are thinking, a concept that behavioral scientists call metacognition.

Cultural self-understanding is a particular type of awareness that explores who you are culturally. Culture is bigger than any one of our identities. It is the combination of who we are and how we see and interpret the world. It may include our race/ethnicity, nationality, religion, geographic location, values, and beliefs. Our worldview is formed from our membership in a cultural community.

What Is Culture?

Culture can be defined as the behavioral interpretation of how a group lives out its values to survive and thrive, or, alternately, the unwritten practices, rules, and norms of a group. Most often, we take our culture for granted. It just is. However, our culture drives our behavior. Do we believe in shaking hands, bowing, or kissing when we meet someone new? Is it okay to show your emotions, or does your cultural norm say it is preferred not to be emotionally expressive when you are passionate or even angry about something? What does assertiveness look like in your culture? Is it a positive or negative attribute? It is not until we find ourselves out of our cultural norm that we recognize our own unique cultural patterns.

If you are member of a dominant group (e.g., white, male, heterosexual), you may not have to come out of your cultural comfort zone very often. I often hear leaders and others in training sessions struggle with an exercise that explores their cultural identity. Some say, “I don’t really have a culture.” While others say, “I just never thought about it before,” and in the end find the exercise very self-revealing. Everybody has a cultural connection. There is no such thing as a view from nowhere. We get our worldview from somewhere, and it is in uncovering where and how that we enhance our cultural self-understanding.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a critical concept in understanding our identity and adds to the complexity of self-understanding. An example of how intersectionality manifests is reflected in the experiences of the gay, Muslim, Middle Eastern employee who called out his multiple identities in Chapter 1. Intersectionality theory acknowledges the overlapping and interdependent nature of simultaneously being a member of several historically marginalized groups.

First introduced by Sociologist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 in a critique of feminist and antiracism discourse, intersectionality challenged the effectiveness of gender and civil rights ideologies, which had traditionally excluded the unique experiences of black women.3 For women of color, the compounding effects of belonging to multiple marginalized identities (e.g., black, woman, low socio-economic class) created a unique experience that was oftentimes overlooked in the inquiry into and development of solutions that sought to address race and gender issues. According to intersectionality, the context and degree to which we experience power or marginalization is influenced by the intersection of our varying identities.

Those who are part of multiple non-dominant groups may be more sensitive to and aware of their differences, and are perhaps uncomfortable colluding with the cultural “rules” of the dominant group that are unfamiliar. The cultural exercise below encourages self-understanding. The questions posed are, more often than not, easier for those who are part of non-dominant groups (e.g., people of color, LGBTQ, those from a different religious group) to answer.

However, whether in the majority or minority, it is important to increase your cultural self-understanding.

Ask yourself these questions:

Where did I grow up, and what was the culture of my community growing up?

What did I learn about right/wrong, good/bad growing up?

What are my values and beliefs, and how have they changed over time?

If I had to describe a cultural community to which I belong, what would I say?

![]() What is my cultural identity?

What is my cultural identity?

Race/ethnicity

Generation

Religion

Education

Profession

Political persuasion

How does my cultural identity shape who I am and how I think?

![]() What is my mindset about difference?

What is my mindset about difference?

Are we basically all the same as humans?

Are we more alike than we are different?

Is color blindness/gender blindness the best way?

Do I think my group’s cultural norms are better than other people’s?

Are differences normal, inevitable, something to learn about?

Gaining cultural self-understanding is not necessarily intuitive, especially for those in the dominant group. It takes time. Spend time with yourself understanding who you are. Seek a partner, perhaps a family member or a trusted friend, who can help you on the journey.

GETTING BEYOND “BLINDNESS”

When someone says to me, “I don’t see you as a black person,” I interpret that as them not seeing me for who I am—that they don’t see this core aspect of my identity (being black) as important. While I recognize that most people who make this statement mean well, they are saying that they see me as the same as them—I am their equal. They are, in effect, minimizing my difference. The reality is, I am different. To have bold, inclusive conversations, we must first acknowledge that there are important differences that make a difference.

Since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, when it became illegal to discriminate based on race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, and religion, we have focused on treating people the same, being color blind, gender blind, or blind to any differences. The legislation says that we should treat people equally. However, equal and the same are not synonymous. Many strive to practice the Golden Rule (treating others the way you want to be treated), rather than the Platinum Rule (treating others the way they want to be treated). You will not know how others want to be treated unless you have some level of understanding about others. Operating from the assumption that you know what is good for others because you know what is good for you can thwart efforts for mutual understanding.

The Golden Rule is a good starting point, but bold conversations are much more effective if you have the capability to practice the Platinum Rule. If we assume that we are basically all the same and minimize our differences, we have no incentive to spend time learning about others who may be from a different race, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and so on, because we feel there is essentially nothing to learn.

FINDING COMMON GROUND

A “sameness” mindset, however, can be a good place to start when there are polarized views. You want to find the common ground, a place of agreement from which to start the conversation. For example, we all want our communities to be safe, or we all want the best for our children. However, we may have different worldviews of how to accomplish these goals. Discovering our commonalities builds trust and an opening for deeper dialogue.

When we are polarized, the human tendency is to judge. We are so entrenched in our own beliefs, it sends us to our own corners, rather than to a place of non-judgmental curiosity about why we have different views. For example, white people may be more likely to hold the worldview that police officers are our friends. Based on experience, minority communities, particularly black communities, may have learned the exact opposite. To have bold conversations we have to explore our similarities (e.g., we all want our communities to be safe) before we can effectively talk about our differences.

My sister-in-law is Muslim. For many years, we did not talk about religion. While I respected and loved her very much, I had no knowledge of Islam. I thought it to be a very different religion from my own Christian beliefs and quite frankly I was afraid to ask questions because I did not want to appear ignorant. I felt we were polarized and it was best not to talk about it until one day in a conversation she mentioned Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I was stunned. I did not think that Islam would have any of the same Christian characters that I was familiar with. My point is that it was not until we found common ground—something that was the same—that we were able to continue to share commonalities and eventually begin to explore our differences.

“Going Along to Get Along”

Often, individuals from historically marginalized groups minimize their differences, or take a “go along to get along” stance, as a means of survival, which, in effect, can validate the “we are all the same” worldview. People with visible differences from non-dominant groups may find that to be successful they have to accentuate their similarities and downplay their differences. Differences may make majority group members uncomfortable. This dynamic makes it even more difficult to engage in meaningful conversations. Dominant group members may over-assume similarities, and minority group members might feel a need to understate differences. These two dynamics void each other out and result in no progress on really understanding the perspective of the other.

Bold conversations can happen only when there is an openness to acknowledge that there are differences that make a profound difference in perceptions and outcomes for many of us.

Stereotype Threats

A stereotype threat, a term coined by Claude Steele, is the expectation or the fear that one will be judged based on a negative stereotype about one’s social identity group, rather than on actual performance and potential.4

Stereotype threats have been proven to have an immediate impact on performance. One study on stereotype threats and women’s performance in math found that women are more likely to perform just as well on math tests as their male counterparts when the test is described as not producing gender differences in performance.5 This condition countered the stereotype that women do not do as well in math as men.

Similar results were found among African American students on standardized tests.6 Steele’s study found that African American students were less likely to perform well when the test was described as diagnostic of intellectual ability. Even if the test was not an ability diagnostic, black students underperformed due to their fears of colluding with stereotypes that suggest blacks are intellectually inferior. They performed better when the test was described as non-diagnostic.

Although there are numerous laboratory studies in academic settings that show the impact of stereotype threats on performance, the influence in work settings has not been explored very much.

In a paper in The Counseling Psychologist, the authors explore the impact of stereotype threats at work. The authors contend that in a workplace where an individual is in the minority, there is a greater likelihood that this individual will experience stereotype threats. They posit that there are three potential responses to stereotype threats in the workplace:7

![]() Overcompensation—To prove that the stereotype does not apply to them or that they are not a typical member of their group, people may distance themselves from the negatively stereotyped group and assimilate by trying to behave and act more like those in a more positively viewed group. This is akin to minimizing their differences, the “go along to get along” phenomena.

Overcompensation—To prove that the stereotype does not apply to them or that they are not a typical member of their group, people may distance themselves from the negatively stereotyped group and assimilate by trying to behave and act more like those in a more positively viewed group. This is akin to minimizing their differences, the “go along to get along” phenomena.

![]() Discouragement—When an individual believes that no matter how hard he/she tries, the stereotype is just too big to overcome, this can manifest in disengagement from negative evaluations about one’s group in order to preserve self-esteem. For example, from a psychological perspective, negative performance evaluations are discounted by the individual and not deemed relevant to his/her self-perception. In the short term, disengagement may work in preserving one’s self-esteem, but in the long term, it may negatively impact motivation and performance because individuals believe they have no control over the outcomes.

Discouragement—When an individual believes that no matter how hard he/she tries, the stereotype is just too big to overcome, this can manifest in disengagement from negative evaluations about one’s group in order to preserve self-esteem. For example, from a psychological perspective, negative performance evaluations are discounted by the individual and not deemed relevant to his/her self-perception. In the short term, disengagement may work in preserving one’s self-esteem, but in the long term, it may negatively impact motivation and performance because individuals believe they have no control over the outcomes.

![]() Resiliency—The authors believe many underrepresented groups actually manage to be resilient to stereotype threats in the workplace. It may play out in an advocacy or champion role, as one who supports learning and training in the organization to alleviate stereotypes. Other responses in this category include pointing out positive attributes of the targeted identity group and collective action, such as affinity groups that work to support inclusive practices.

Resiliency—The authors believe many underrepresented groups actually manage to be resilient to stereotype threats in the workplace. It may play out in an advocacy or champion role, as one who supports learning and training in the organization to alleviate stereotypes. Other responses in this category include pointing out positive attributes of the targeted identity group and collective action, such as affinity groups that work to support inclusive practices.

It is important to understand the role of stereotype threats in developing the capability for bold, inclusive conversations. If the stereotype threats of “less intelligent” or “less articulate” are unconsciously playing out, it will certainly impact the effectiveness of the dialogue.

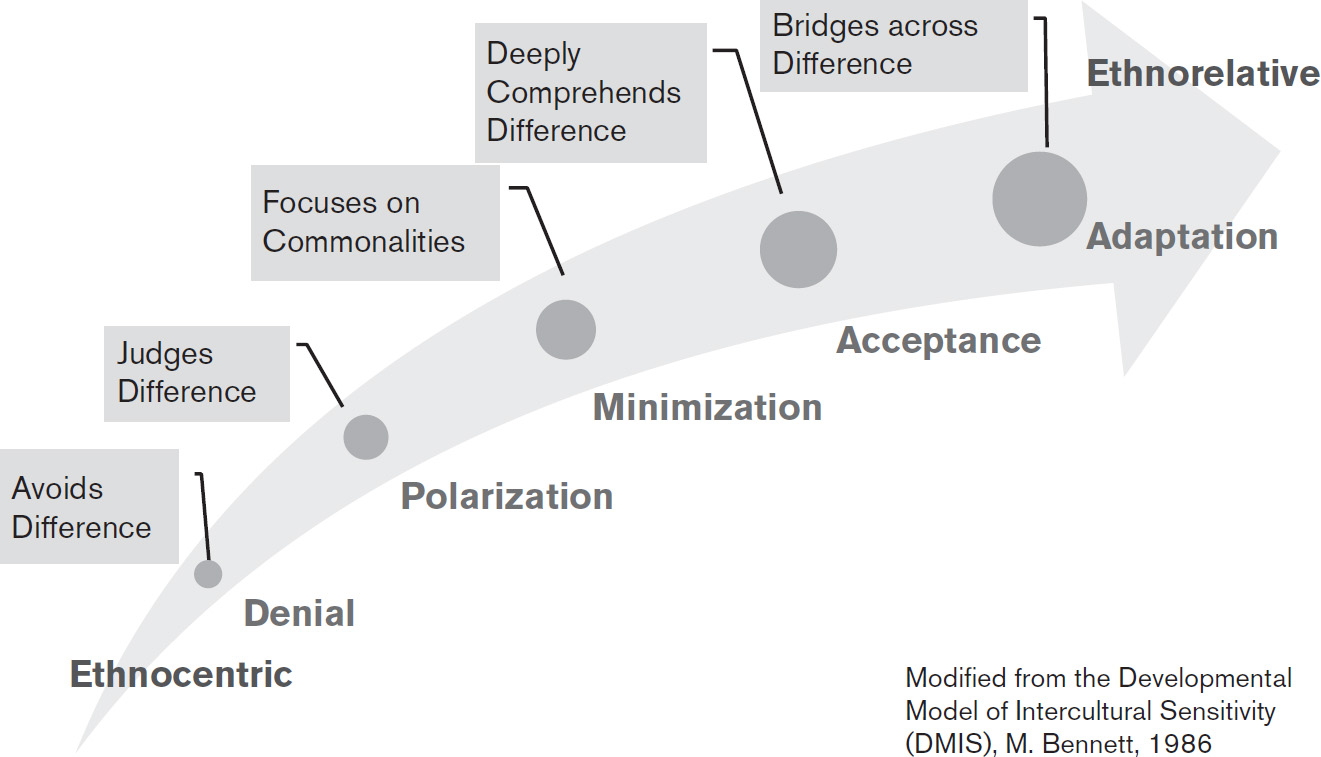

IDC Helps Us Understand How We Experience Difference

A useful model for assessing how we experience difference is the Intercultural Development Continuum (IDC), which is assessed by the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI), developed and owned by IDI’s president, Dr. Mitchell Hammer.

The theory is that as our experience with difference expands, we have a greater capacity to understand and bridge the complexities of cultural differences. It is a developmental model that contends that we advance through stages of greater capability to meaningfully address differences. Figure 2 highlights the developmental stages.

If we have had no experience with difference, we might be at the first stage, denial, where one would avoid or be disinterested in differences. The next stage is polarization, where we judge differences. Both denial and polarization are early developmental phases where we have little experience or knowledge of differences and can see difference only through our own cultural lens (i.e., an ethnocentric worldview). When we are at polarization, the goal should be to move to minimization. The theory is that you must move through each stage as you develop cultural competence.

FIGURE 2. INTERCULTURAL DEVELOPMENT CONTINUUM

The third stage is minimization. This is where we practice the Golden Rule. Here, the mindset is that we are essentially all the same and any differences are inconsequential because we are all human. Minimization is where most people fall on the continuum because we have essentially been taught to minimize differences. As mentioned above, historically marginalized groups often minimize their differences as a way to “go along to get along.” Individuals from dominant group identities minimize when they do not have a deeper comprehension of differences. Minimization can be a good place to find common ground but is insufficient for bold conversations.

The two stages that reflect a much deeper understanding of difference—a recognition that there are differences that make a difference and the need for those differences to be understood and bridged—are acceptance and adaptation (ethnorelative stages). At these stages, one embodies a more complex way of experiencing difference and is able to view the world from the perspective of other cultures. Acceptance does not mean agreement. It means that we accept that there are a number of ways that cultures experience the world and that we are curious to learn more about our differences. At the adaptation stage, not only do we recognize patterns of differences in our own and other cultures, but we also know how to effectively bridge those differences in mutually respectful ways. The Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI), a 50-question online psychometric inventory, is effective in providing a baseline of your individual (or group’s) cultural competence, enhancing your self-understanding, and ultimately, gauging your readiness for bold, inclusive conversations (www.idiinventory.com).

FACE YOUR FEARS AND CHOOSE COURAGE

It takes courage . . . to endure the sharp pains of self-discovery rather than choose to take the dull pain of unconsciousness that would last the rest of our lives.

Marianne Williamson, A Return to Love: Reflections on the Principles of A Course in Miracles8

There is always some level of fear when you delve into unknown territory. Bold conversations require venturing outside one’s comfort zone, which can be intimidating. The role of cultural identity makes dialogue even more complicated, because our identity groups are linked to a broader historical and social context. Sometimes history is uncomfortable and traumatic, which can make some of us fearful of having these discussions and more inclined to want to forget (or even deny) the past. For example, dialogue around race usually elicits fear and discomfort, largely due to the history of racism and the historical oppression of people of color. It is much easier for many to see these ills as isolated moments from the past. However we cannot forget or deny them because the intolerance, bigotry, and hatred have not disappeared. Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, racism, and homophobia are still modern-day issues that continue to divide, polarize, and lead to violence and senseless killings. Instead of avoiding these conversations, we must identify strategies that alleviate our fears and position us to effectively engage in bold conversations as a means to solve these menacing problems.

Let’s pause here. Do you experience a sense of fear when engaging in bold conversations? If so, ask yourself what am I afraid of? These questions are relevant whether you are a member of a dominant or non-dominant group. Are you afraid . . .

![]() of offending?

of offending?

![]() of not knowing enough about the subject?

of not knowing enough about the subject?

![]() of the conflict that might arise?

of the conflict that might arise?

![]() of remembering some negative outcome from a previous dialogue?

of remembering some negative outcome from a previous dialogue?

![]() that you will be judged?

that you will be judged?

![]() that the other person won’t “get it”?

that the other person won’t “get it”?

![]() of the possibility of becoming emotional or angry?

of the possibility of becoming emotional or angry?

As part of your self-discovery process, really probe why you might be afraid of having a bold conversation. Try to lean into your discomfort. Most things that are hard create some level of discomfort. By the same token, facing the difficulty and working through it brings satisfaction in the end.

It takes courage to face our fears. A 2012 Psychology Today article highlights six attributes of courage: (1) feeling fear, yet choosing to act; (2) following your heart; (3) persevering in the face of adversity; (4) standing up for what is right; (5) expanding your horizons and letting go of the familiar; (6) facing suffering with dignity and faith.9 Practice finding your courage to have bold, inclusive conversations.

Along with courage, we need cultural humility to engage in conversations across difference. A 1998 article in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved describes cultural competence in clinical training as a detached mastery of a theoretically finite body of knowledge. Cultural humility, on the other hand, incorporates lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redress the power imbalances in the patient/physician dynamic.10 Cultural humility is the ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the other person.

WE ALL HAVE BIASES

We all have biases, but most of us are unaware of how they manifest in our decisions and interactions. This is because social scientists assert that most of our biases are unconscious, and our unconscious biases drive 99 percent of our behaviors. Unconscious bias is a bias that happens automatically and is triggered by our brain making quick judgments and assessments of people and situations, influenced by our background, cultural environment, and personal experiences. How can you address your unconscious biases if you are unaware of them?

Know Your Culture: Increase self-understanding as discussed earlier. Know your own culture, why you believe what you believe, your history, and early experiences that have shaped your value system.

Change, Expand the Story: If unconscious biases are built up over time by the mind ingesting biased, partial, and negative messages, then the work to undo them is in meeting these messages with positive, affirming, counter-narratives that are equally powerful. Counter-narratives are only possible when you know what they are. If you don’t know other stories, you cannot change the one that is in your head.

Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie, in a compelling TED Talk called “The Danger of a Single Story,” cautions that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk stereotyping and vast misinterpretations.11 In her talk, she says if the single story of Africa is that it is an undeveloped, poverty-ridden continent, you miss the other stories, like hers—growing up in a middle-class household with college-professor parents; or the rich history of a place like Timbuktu, the home of the first university in the world. What stories do you have about individuals, groups, and cultures that are different from yours? Is it a single story, or do you have several narratives in your mind—some perhaps good, others not so good, but a balance?

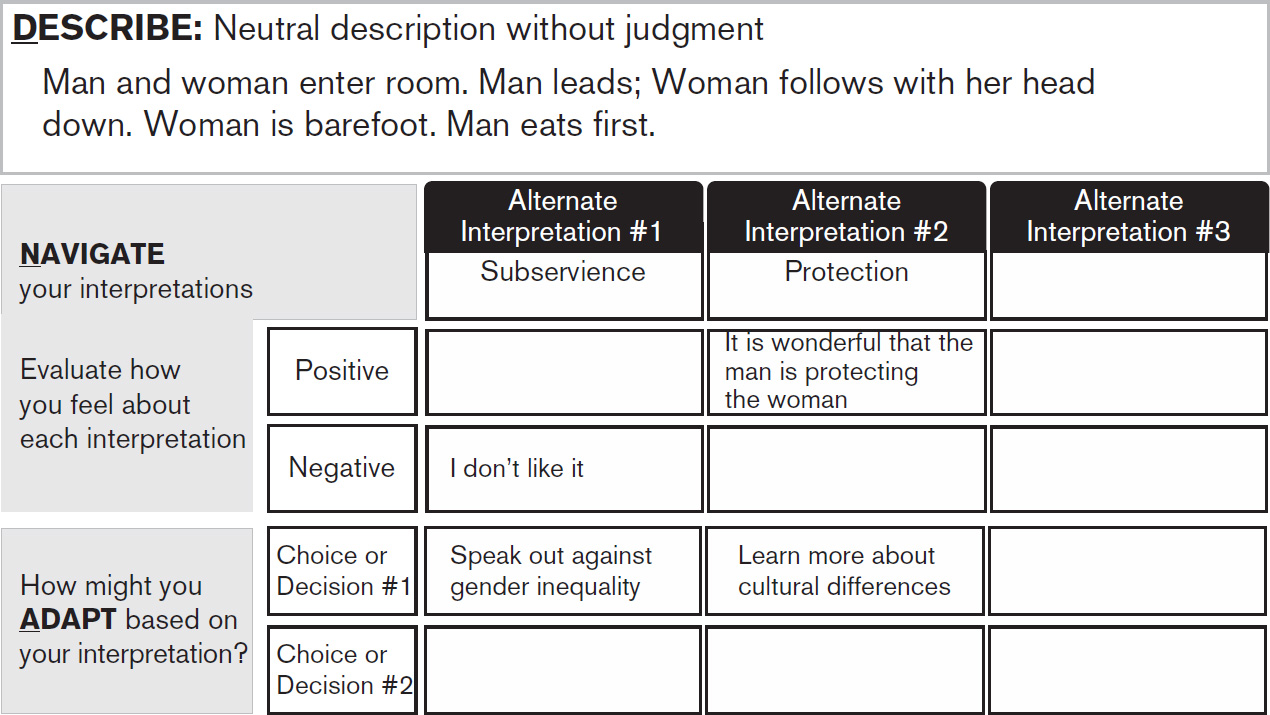

Describe before You Interpret: I do an exercise with clients in which I show a short video depicting the following interaction.

A man and woman walk silently into the room, never speaking, and the woman walks in behind the man with her eyes looking slightly downward. The man is wearing shoes and the woman is barefoot. The man comes to a chair and sits down, and then the woman sits on the floor next to him. The man acts like he’s eating something from a bowl. He then passes the bowl to the woman, and she eats from the bowl. When she’s finished, the man puts his hand just above the woman’s bowed head—it looks as though he’s almost pushing her head up and down—though his hand never actually touches her head. Then, the man stands up and leaves first, and the woman leaves behind him.

I ask them what they see. Words like subservience, male dominance, and gender inequality always surface—which are judgments and interpretations, rather than descriptions or observations. After that, I explain what is really happening in the video. “In the scene you just saw, the woman and the Earth are actually the two most sacred and revered aspects of their specific culture, so much so, that only the woman is holy and good enough to sit on the ground and touch it with her feet. Men can only experience the Earth through the woman. The man is charged with testing the food before it is proven fit for the woman; in case it is poisoned, he would die first. He is also charged with walking in first to deflect any attacks, and thus, to safely lead the way for her to walk unharmed.”

Next I ask, “How did you see subordination, subservience, gender inequality?” Had they actually described their observations, they would have said “The woman had her head lowered” or “She was barefoot.” However, their interpretations were based on what those behaviors mean for them. I follow up with the question “Where do our interpretations come from?” and the group recognizes that our unconscious biases direct our interpretations.

The Winters Group has developed a tool called DNA that supports us in being more intentional in naming and challenging our interpretations. DNA stands for Describe, Navigate, Adapt.

FIGURE 3. THE WINTERS GROUP DNA TOOL

(Adapted from D.I.E., Kappler and Nokken,1999.)

Describe: First describe the behaviors and actions you see. Be careful not to let your personal judgments influence what you observe.

Navigate: Navigate your understanding. Be aware that your interpretations are influenced by the behaviors of your culture. What are alternative interpretations?

Adapt: Once you feel you have a pretty good understanding of the behaviors and actions you observed, begin to think of ways to navigate the situation effectively using mutual adaptation skills.

I ask participants to think of alternative interpretations via the DNA tool. Figure 3 is an example of how one might approach alternative interpretations using the earlier video, laying out the steps of describing without judgment, navigating and evaluating interpretations, and articulating possible adaptations. If your interpretation of the behaviors is “subservience,” you would likely evaluate that negatively. If, however, your interpretation is that the man was protecting the woman, your evaluation and how you would adapt might be very different.

The DNA tool is useful in helping us to see beyond the single story (adapted from Nam & Condon, 2010).12

ACKNOWLEDGE YOUR POWER AND PRIVILEGE

Power and privilege determine who is invited to the table, who has access, and who can make decisions. Power also refers to the ability of individuals or groups to induce or influence systems and the beliefs or actions of other persons or groups. One’s level of power or access to power is largely dependent on one’s social status and group membership in various social categorizations, including race, class, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, age, religion, nationality, immigrant status, ability, and weight.

Privilege, at its essence, refers to the advantages that people benefit from based solely on their social status. It is a status that is conferred by society and perpetuated by systems that favor certain groups. This status is not necessarily asked for or appropriated by individuals, which is why it can be difficult for people to see their own privilege.

Power and privilege are relative. We all have it to a certain extent in different situations. However, from a systemic view, dominant groups in society have benefitted the most from unearned power and privilege. As you think about bold, inclusive conversations, consider, regardless of whether you are from the dominant or non-dominant group, what power or privilege you may have. For example, you may be a person of color—a group that has historically been without power and privilege—but in this situation, you are the manager, which puts you in a position of power from which to act.

Historically marginalized groups need to understand and recognize the impact of power and privilege without blaming dominant group individuals for this condition. No effective conversation comes from the blame game. Power and privilege is systemic and complex. I also want historically marginalized groups not to automatically think they are powerless. I too often hear the sentiment: “What can I do? White people hold all of the power.” You can change your perspective and definition of power. Power does not have to be a zero-sum game. It can mean shared power. We can see it as infinite. In his book, Power: The Infinite Game, Michael Broom contends that the infinite perspective of power means that we see the end goal as not winning or losing but rather as continuing the game and maintaining it.13

A finite perspective of power leads to a defensive stance where deception and secrecy are the preferred strategies. When we think of power as infinite, it evokes cooperation and openness. Bold, inclusive conversations happen only with an infinite power worldview.

Dominant group individuals should work on understanding the impact of their unearned power and privilege. Nondominant groups should not use that as a crutch but rather change their mindset, and, consequently, their behavior will change. If you see yourself as powerless, you act powerless. If you see yourself as having infinite power, you press on with confidence and resolve.

Here are some general, then more specific, questions that you should ask yourself about power and privilege, as part of your readiness to have a bold conversation.

![]() What is my positional power in this situation?

What is my positional power in this situation?

![]() Do I have power simply because I am a member of a dominant group?

Do I have power simply because I am a member of a dominant group?

![]() What influence do I have over the outcomes?

What influence do I have over the outcomes?

![]() If I am not a member of the dominant group, does the power and privilege of those who will be a part of the conversation concern me?

If I am not a member of the dominant group, does the power and privilege of those who will be a part of the conversation concern me?

![]() As a member of the non-dominant group, what power do I have in this situation? Do I see power as finite or infinite?

As a member of the non-dominant group, what power do I have in this situation? Do I see power as finite or infinite?

![]() Can I essentially live being unaware on a day-to-day basis of my identity group (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, immigrant status)?

Can I essentially live being unaware on a day-to-day basis of my identity group (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, immigrant status)?

![]() Is it likely that I will be ostracized by my friends and family because of my sexual orientation?

Is it likely that I will be ostracized by my friends and family because of my sexual orientation?

![]() Can I demonstrate my religious beliefs without fear?

Can I demonstrate my religious beliefs without fear?

You should explore these and a host of other questions about power and privilege as part of your readiness to have a bold conversation. This mention of power and privilege just scratches the surface. I advise that you do some more research to gain a deeper understanding of this phenomena. It is at the core of our social issues, fuels polarization, and precludes the possibility of equitable dialogue.

If those involved are not ready for the complex discussions around power and privilege conversations, the result can be deeper polarization. It is not the first place you want to start if the participants are fairly new to having these types of conversations and there is a great deal of polarization.

CHAPTER 2 ![]() TIPS FOR TALKING ABOUT IT!

TIPS FOR TALKING ABOUT IT!

![]() Remember that the ability to engage in bold, inclusive conversations is a journey that requires cultural self-understanding, addressing our biases and fears, and understanding our power and privilege.

Remember that the ability to engage in bold, inclusive conversations is a journey that requires cultural self-understanding, addressing our biases and fears, and understanding our power and privilege.

![]() Know your culture. Everybody has a cultural identity that shapes their worldview. We don’t always consciously realize how our culture informs our perceptions and behavior.

Know your culture. Everybody has a cultural identity that shapes their worldview. We don’t always consciously realize how our culture informs our perceptions and behavior.

![]() Resist the tendency to minimize differences. We tend to minimize our differences and overstate our similarities, leading us to practice the Golden Rule rather than the Platinum Rule.

Resist the tendency to minimize differences. We tend to minimize our differences and overstate our similarities, leading us to practice the Golden Rule rather than the Platinum Rule.

![]() Resist the single story. Many of us only have a single story about those who are different. Meaningful dialogue will occur only if we learn more than one story about others.

Resist the single story. Many of us only have a single story about those who are different. Meaningful dialogue will occur only if we learn more than one story about others.

![]() Take the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI). It is a useful tool for assessing our readiness for bold, inclusive conversations.

Take the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI). It is a useful tool for assessing our readiness for bold, inclusive conversations.

![]() Recognize your power and privilege. Power and privilege are key determinants in the nature and tenor of cross-difference dialogue.

Recognize your power and privilege. Power and privilege are key determinants in the nature and tenor of cross-difference dialogue.

![]() Know your level of readiness before you engage in bold, inclusive conversations.

Know your level of readiness before you engage in bold, inclusive conversations.