We have just seen how underlying macroeconomic imbalances accumulated over the years. However, problems were deeply rooted in the economy well beyond macroeconomic variables; they were also present in the financial sector. Chapter 3 reviews some of the triggers that led to the global financial crisis and shows how the crisis spread across sectors and throughout the European economy.

The Real Estate Bubble in the United States

The mortgage market developed extraordinarily in the United States over the 2000s. Housing prices had been consistently increasing for years. Financial innovation allowed for many people to buy properties beyond their means. They were also encouraged by the government to do so to boost growth, particularly after 9/11. To achieve that, all kinds of new formulas were created: mortgages with teaser rates—with an initial very low rate—mortgages with balloon payments—a significant amount of capital is left to be paid at maturity—mortgages with negative amortization—with payments smaller than the interest charged and, therefore, with outstanding balance increasing over time—“liar loans”—in which borrower’s statements about her income level is not verified by the lender—and others. All these subprime mortgages entailed repeated refinancing. This system ostensibly worked perfectly as long as real estate prices continued to increase. People were happy with their improving standard of living and banks were happy with their increasing income.

The process of securitization completed the system. Sets of mortgage loans were packaged together, securitized, and then sold in the markets. This promised several advantages: the risk could be spread across the world instead of remaining concentrated on the originators—the banks providing the loan to the consumer. Secondly, securitization enabled the creation of tranches: a large proportion of risky loans could become an AAA product of the highest quality, thanks to the stamp of rating agencies.

However, there were important flaws in the system. The originators did not have incentives to control and mitigate the risks and rather focused on increasing their income in the form of fees. Investors around the world were buying AAA-rated American receivables, assuming their top quality without necessarily investigating what was behind. This was definitely not sustainable.

The Model Starts to Totter

To strengthen their resilience and compensate for their intrinsic weak position, banks need to comply with a series of prudential requirements (see Chapter 1). Among other things, banks are required to maintain balanced liquidity positions at the end of each day. Interbank lending markets allow banks to manage their liquidity positions by placing excess liquidity or by obtaining liquidity to compensate for a deficit. In principle, interbank markets are very safe so that prices—or spreads—were traditionally very low.

However, new developments in the U.S. real estate markets were about to change the financial landscape. After peaking in 2006, U.S. housing prices started to decline and thereby threatened the whole construction described in the previous section. Declining prices made the actual value of the portfolios of subprime loans quite uncertain. This raised concerns about the banks holding those portfolios such as Bear Stearns or Merrill Lynch in the United States but also other banks around the globe, from BNP Paribas to Bank of China. This impacted interbank markets: the reluctance of investors with excess liquidity to lend to “suspicious” banks led to an increase in the price and a reduction in the amounts underwritten. Between summer 2007 and summer 2008, the market was embedded with uncertainty about how many toxic assets banks were holding and their actual value. In most cases, those toxic assets represented a fraction of the aggregated banks’ balance sheet only; however, some small banks were failing and a few others were bailed-out by public authorities.

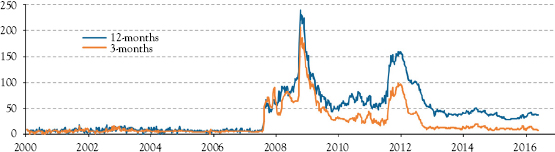

In September 2008, the overnight failure of Lehman Brothers, the fourth largest investment bank in the United States, meant a change in the game. The market was shocked by the fact that a leading bank had failed; the same fate could fall on any other bank. Confidence evaporated. The immediate soar of spreads in the interbank markets to over 300 basis points (Figure 3.1) signals that no bank was willing to lend to another anymore, in other words, interbank markets dried up.

Figure 3.1 Risk perceived in the interbank market, Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS)—Euribor spread, basis points

Interbank markets were traditionally perceived as having very low risk as reflected in the very low spread. The extend of the turmoil generated by the subprime crisis in 2007 and of the panic following the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008 is reflected in the spikes observed in the spreads. Since then, spread have significantly declined but remain above precrisis levels.

Source: Bloomberg and own calculations.

Support by Central Banks and Governments

The central banks—among them the European Central Bank (ECB)—had to step in to avoid the collapse of the financial system. In its role as a “lender of last resort,” the ECB provided as much liquidity as the banks asked for and provisionally substituted interbank markets: the liquidity provided by the ECB to commercial banks soared to over €800 billion at an interest rate that dropped to 1 percent (Figure 3.2).

At the same time, governments implemented a series of policies aiming at making confidence return to markets. Banks would not lend to each other as they feared not to be reimbursed at maturity. Therefore, governments issued guarantees on the bonds of banks in their jurisdictions: in case a bank was unable to reimburse a bond, the State would step in and pay on its behalf. By December 2008, EU States had granted up to €400 billion of guarantees on their banks’ bonds (Figure 3.3). These public guarantees improved investors’ confidence as reflected in declining spreads (Figure 3.1) and in the reactivation of the volumes in interbank markets. The United Kingdom, Germany, and France were the countries with the largest support to their financial systems in the initial phases of the crisis.1

Figure 3.2 Liquidity provided to euro area banks by the ECB

The European Central Bank reacted to the outbreak of the crisis by offering increasing amounts of liquidity at a lower cost to banks.

Source: ECB.

Figure 3.3 State guaranteed bonds, € billion

In order to restore confidence on financial institutions, governments guaranteed the bonds issued by their banks.

Source: European Commission.

Notes: Guarantees granted by the Irish government reached a peak of €285 billion in 2009 because of the blank guarantee.

In parallel to the financial turmoil of 2008–2010, economic activity started to slow down and unemployment started to rise (Figures 1.19 to 1.21). The excesses and imbalances accumulated over the years across EU countries started to surface and increasing numbers of households and companies started to have difficulties to repay their credits. Confronted with losses and more aware of the (low) creditworthiness of potential borrowers, banks restricted the provision of new loans. All of this pushed up the level of nonperforming loans (Figure 3.4) and further eroded bank income on top of the contagion stemming from the U.S. subprime market.2

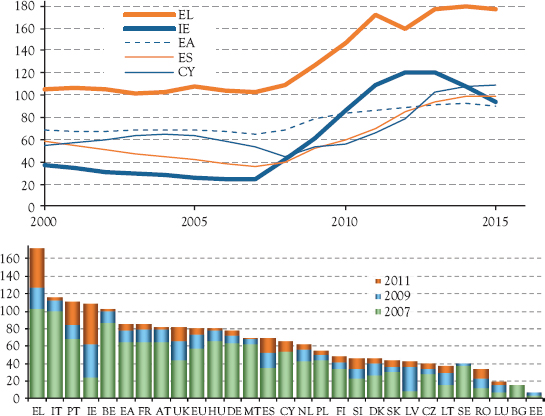

Figure 3.4 Nonperforming loans, percentage

The slowdown in real economy—and the excessive ease in the provision of credit in the pass—translated into increasing nonperforming loans, particularly in certain countries.

Source: ECB.

Notes: Guarantees granted by the Irish government reached a peak of €285 billion in 2009 because of the blank guarantee.

A potential problem—confidence—was materializing into actual losses. Therefore, governments also stepped in to directly inject capital on the many banks that have suffered massive losses. By December 2012, EU Member States had injected more than €300 billion of public funds into the banking system (Figure 3.5).

Erosion in Public Finances and the Sovereign Crisis

The public interventions helped stabilize financial markets; however, they also eroded public accounts. By 2011, public debt in many countries had gone well beyond the 60 percent threshold established by the Stability and Growth Pact (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.5 Capital injected in banks by public authorities, € billion

Banks incurred in large losses bringing them, in some cases, to or close to insolvency. No private investors were willing to support such financial institutions, so that governments stepped in and bail out financial institutions through large public capital injections.

Source: European Commission.

Figure 3.6 Public debt, percentage of GDP

The automatic stabilizers—for example, unemployment benefits—and the funding injected to support financial institutions translated in increasing amounts of public debt.

Source: Eurostat.

With the introduction of the euro, government bond yields converged across countries (Chapter 2). Although the response to the crisis was coordinated at European level, each country remained responsible for its own banking system. On the wake of the erosion in public finances, investors realized that not all the countries were the same and asked for increasing interest rates to lend money to the weakest countries (Figure 3.7). This in itself could only worsen the situation.

Figure 3.7 Yields on 10-year government bonds, percentage

The deterioration in the fiscal position of some countries and in their economic performance translated into increasing government bond yields.

Source: ECB.

Transmission to the Real Economy and Second Round Effects

The problems in the financial sector forced governments to step in and put pressure on public finances. Tighter lending conditions confronted by governments impacted back on national banks: Investors asked increasing interest rates for lending money to banks in the weakest countries. Indeed, high correlations between sovereign credit default swaps (CDSs) and bank CDSs are observed within the countries under fiscal stress independently of the strength of the banks themselves (Figure 3.8). Increasing CDSs signal increasing perceived risks and, therefore, banks are confronted with increasing cost of funding.

Moreover, banks translated their increasing funding costs to their customers by asking for higher interest rates on their (new) loans and by restricting the effective amounts lent. In other words, banks in countries under fiscal stress were unable to translate the declines in the ECB rates (Figure 3.2) into the rates charged to customers (Figure 3.9). The difficulties in the real economy fed back to the financial sectors through households and corporations that became unable to repay their credits (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.8 CDS spreads, 5 years, selection of countries

The deterioration in government finance and the economic performance impacted not only the risk premium of governments, but also translated to their national banks as reflected in increasing CDS spreads.

Source: Bloomberg.

Figure 3.9 Interest rates on new loans, percentage

Banks experiencing difficulties to finance themselves passed their increasing costs to their customers in the form of higher lending rates. Other banks experienced less constrains and reduced their lending rates more in line with the declines in the policy rate. As a consequence, a large dispersion in lending rates was observed across the countries sharing the single currency.

Source: ECB.

Conclusion

In Chapter 1, we discussed the interdependence of all the agents in an economy. In this chapter, we show how, following some triggering effects, the underlining structural weaknesses embarked the economy into a vicious cycle: a slowing economy eroded the bank and public accounts and fed back into an even slower growth (Figure 3.10). As it will be shown throughout the Volume II, the goal of public authorities evolved from addressing isolated bouts of problems to stop the vicious cycle with a more systematic approach.

Throughout this Volume I, we have reviewed the structure of the European financial sector, the factors leading to the global economic and financial crisis as well as how the crisis unfolded. Volume II will present how public authorities, both at national and EU level, responded to the crisis on a temporary basis to address some urgent and ad hoc issues as well as on a permanent basis to tackle structural problems in certain policy areas.

The response was orchestrated from many different fronts. The emergency financial support provided to both financial institutions and to sovereigns under stress is discussed in Part C. These efforts aimed at stabilizing the system through a sort of fire brigade. Fixing the flaws from a more structural perspective is discussed in Parts D (dealing with the regulatory reform) and E (discussing macroeconomic policies).

Figure 3.10 Feedback loop

The financial difficulties in the financial sector translated into the real economy and public finances and fed back to the financial sector in a sort of doom loop.

Source: Own elaboration.

Finally, Part F closes Volume II and the book by summarizing the different pieces of the policy reaction to the crisis and how they all fit together. It also reviews the future vision the European Union would like to head to and briefly discusses the potential challenges the European Union is likely to face in its way towards achieving that vision.

1 Ireland and Denmark represent specific cases as the government granted a blank guarantee to all the bonds issued by the banks under their jurisdictions (and not only guarantees to new issuances as in the other countries).

2 The discussion about the reaction in the United States, which was also significant, goes beyond the scope of this book. The reader can consult, for instance, Krugman (2013); Mian and Sufi (2014); Stiglitz (2010); or the final report of the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (Angelides et al. 2011).