6

Understanding Motivation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Specify the importance of managers’ understanding human motivation.

• Identify the stages in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

• Distinguish between motivators and hygiene factors for a given job situation.

• Describe the application of expectancy theory, equity theory, and organizational behavior modification to motivation on the job.

In Chapter 1, we discussed management as the process of accomplishing goals through other people. In order to do this, managers lead and direct subordinates in specific activities that will result in desired outcomes leading to the attainment of the organization’s strategic goals. Because managers must rely on others to accomplish goals, human nature and its relation to behavior and motivation are appropriate concerns of management.

The behavior of people as individuals and in groups at work and in the world at large is often rational, consistent, and predictable. When a person is hungry, he or she consumes food or drink to remove the feelings of discomfort. Sports teams enter contests with a desire to win, even when the odds against them are great. If individuals or an entire neighborhood are faced with pollution problems where they live, they try to remedy the offending situation.

At other times, people’s behavior is irrational. Some people do not eat when they should; others eat regularly, but select a diet that lacks nutrition; others overeat. People may act inconsistently; for example, they may work hard to purchase a home and then allow the home to deteriorate. People may also behave unpredictably—a fact especially worrisome to politicians and poll-takers.

Despite these seemingly random aspects of human behavior, certain universal characteristics can be discerned. Effective managers understand these characteristics and use this understanding to motivate their subordinates.

WHAT IS MOTIVATION?

Motivation has two distinctly different meanings. To a psychologist, understanding motivation means understanding the innermost drives that cause human behavior. Managers, however, are interested in results. To them, understanding motivation means understanding how to get people to act in ways that will get the job done. We often hear managers complain that there is “no motivation” among the members of their work group. For example, take the case of a supervisor on a construction site who has hired a bricklayer to build the chimney. This bricklayer lays 500 bricks an hour and is paid $10 an hour. The supervisor knows it is possible to lay 1,000 bricks an hour. If the supervisor could only “motivate” the bricklayer to work faster, the job would be done in half the time—and for half the cost.

Managers want to encourage desirable behavior and discourage undesirable behavior. In order to be able to do this, they must understand what causes human behavior. While psychologists are concerned with the deep emotional and historical roots of human behavior, managers are interested in only those aspects of motivation that directly account for a particular level of performance on the job. This is the approach to motivation taken in this chapter.

Human behavior, like all activity, has a cause and effect. It does not emerge from nothingness, but is stimulated by force within individuals and the environment. Human behavior is goal-directed, in that people channel their behavior toward the accomplishment of general and specifically desired results. This aspect of human behavior holds even though the particular behavior selected may or may not be able to bring about what is wanted. Individuals perceive their actions as proper, appropriate, and productive for the situations in which they are involved. This perception of human actions as efficacious is the essence of the goal-directed characteristic of human behavior.

Human behavior is also motivated, and this characteristic of human behavior is interrelated with its causal and goal-directed aspects. An unsatisfied goal motivates behavior toward that goal; accomplishment of the goal results in removing the cause of the behavior and the behavior itself. Thus, when an individual feels cold and wants to be warm, this feeling is the stimulus, or cause, for certain behavior: to change into warmer clothes. Dressing warmly to keep out the cold is behavior directed toward the goal of personal, physical comfort; the person is motivated to act in this way to meet the goal. Once the person is warm, the goal has been satisfied. Feelings of cold are no longer a motivator, and the related behavior will cease.

Feedback provides information about the effectiveness of goal-directed behavior. Through the senses and numerous other feedback mechanisms, one experiences the need fulfillment (or lack of it) resulting from one’s actions.

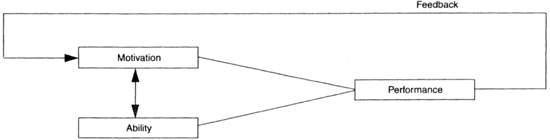

The question for managers in understanding motivation is to explain the reasons behind an individual’s performance on the job. Why does one bricklayer lay 500 bricks an hour while another lays 1,000? Performance may be seen as the result of two factors: motivation and ability (see Exhibit 6–1). A highly skilled bricklayer will be able to lay more bricks per hour than a novice; and a highly motivated novice will lay more bricks than an unmotivated novice. Some highly motivated individuals cannot achieve their goals because they lack the ability, while other highly skilled individuals do not achieve their potential because they lack motivation. A person with low ability but high motivation can be trained and can practice and improve. However, there may be limits to how much a person’s ability can be improved. Ability is a function of experience, practice, and general competence. Motivation, on the other hand, is influenced by numerous job factors—the organization, the peer group, and the manager.

Feedback is another factor that determines performance. Feedback has a direct effect on an individual’s motivation, but only an indirect one on an individual’s ability. Thus, managers can have a more direct effect on their subordinates’ motivation than on their abilities.

Human behavior does not occur in a vacuum. It is initiated by individuals, and they, in turn, react in different ways to stimuli and feedback. In addition, individual actions and reactions are affected by the surroundings in which people find themselves. The manager of a work unit is not usually in total control of the environment and its effect on subordinates’ behavior. Organizational factors also affect the general environment, or context, of the work group. Some of these factors are determined by the manager, who sets the work rules, and some are set by the organization. For example, a manager may be the one to decide how much flexibility a group is given in determining the daily work schedule, while the wages to be earned by the workers in that group may be set by someone other than that manager.

THEORIES OF MOTIVATION

The study of human behavior has produced a number of theories that attempt to explain motivation. These theories identify what motivates individuals to act in particular ways and explain how behavior can change. Some theories explain human motivation by identifying needs that drive people to behave in certain ways. Other theories explain motivation by showing how behavior results from expectations and perceptions of rewards.

Maslow’s Needs Theory

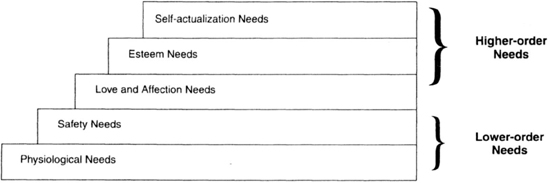

The fundamental goals, drives, or needs of humans can be classified in many ways. The needs hierarchy of Abraham H. Maslow is a classification system widely accepted and used (see Exhibit 6–2). The five basic needs Maslow has identified are, in a hierarchical order: (1) physiological needs, (2) safety needs, (3) love and affection needs, (4) esteem needs, and (5) self-actualization needs (Maslow 1943, 1954).

Maslow postulates that every person tries to satisfy these needs in the order of their ranking, and does not move toward satisfying a need before lower-order needs have been reasonably satisfied. Thus, a person first strives to satisfy physiological needs, and only after they are reasonably satisfied would the person begin to focus on meeting safety needs.

Physiological Needs

Physiological needs pertain to survival and physiological maintenance of the body; examples are the needs for food, drink, shelter, and relief from pain. A person must work so that physiological needs can be satisfied. These needs are reasonably well met by employees through the fact of their employment. Adequate income, rest rooms, ventilation, and comfortable temperatures are examples of things that can satisfy this most basic level of needs. Beyond motivating people to acquire paid employment, physiological needs are not dominant motivators in business and industry.

Safety Needs

Safety needs refer to our desire for freedom from threatening events and surroundings. This kind of freedom necessarily includes feelings of safety and security. Once individuals have provided for their physiological needs, they seek assurance that these needs will continue to be met in the future. The desires for safety and security encompass both economic security and psychological security. Thus, people are concerned about such things as having continual employment opportunities and a flow of adequate income. They also want to be free of the fear of the excessive expenses associated with long-term illness and losses of personal property. Much of the social legislation of recent decades—for example, social security, unemployment insurance, and pension laws—can be traced to people’s safety needs. Psychological security is related to economic security and is the fundamental drive for attaining a level of confidence in our ability to deal with threats and problems.

Love and Affection Needs

Love and affection needs encompass the needs for friendship, affiliation, interaction, and warm feelings from others. These needs follow physiological and safety needs in significance. Human beings are social creatures who are highly desirous of having ties with others and a feeling of belonging. These needs can be met on the job to some extent through the formal organization and the interactions that take place there. Informal social structures also occur naturally within every formal organization, and these afford rewarding and warm experiences for people within their work environment. Since one-third to one-half of a person’s waking hours are spent on the job, these needs affect the way people perform and behave at work.

Esteem Needs

Esteem needs encompass both self-esteem and the esteem of others. Individuals want to feel self-worth and self-respect—strength, achievement, confidence, and independence. They also want the respect of others—a good reputation, prestige, status, fame, glory, recognition, importance, dignity, and appreciation. Managers who wish to motivate employees through esteem needs tend to emphasize the difficulty of work and the skills required for success. They may publicly reward achievement with published performance lists, bonuses, pats on the back, lapel pins, and articles in the company paper. These and other forms of recognition help to promote employee pride. To the extent that the need for esteem is dominant, managers can promote high satisfaction and performance through opportunities for exciting, challenging work and recognition of performance (Hellriegel and Slocum 1989, 432–433). Delegation, discussed in the next chapter, is a means for addressing esteem needs.

Self-actualization Needs

Self-actualization needs are the desires we have for fulfillment by making the best of our abilities, skills, and potential. Traits commonly exhibited by a self-actualized person include initiative, spontaneity, problem solving ability, and a desire for privacy. Managers who motivate by meeting these needs help employees discover the growth opportunities inherent in their jobs. Their strategy for motivation may include involving employees in the decision-making process, restructuring jobs, or offering special assignments that call for special skills (Hellreigel and Slocum 1989, 433). As with esteem needs, delegation is a vehicle for tapping into an employee’s self-actualization needs.

McClelland’s Version of Need Theory

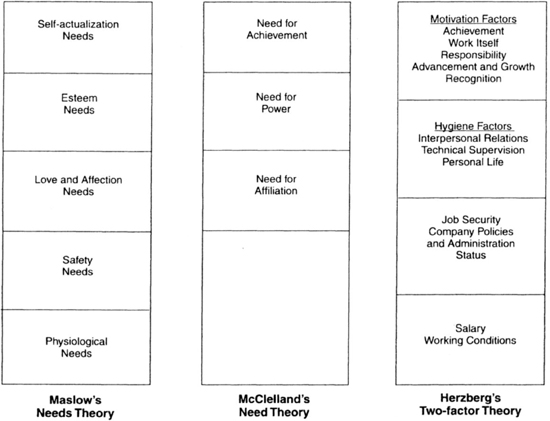

David McClelland proposed a different version of need theory (McClelland 1965). He postulated that three primary motives drive behavior: the need for achievement, the need for power, and the need for affiliation. According to McClelland’s theory, individuals acquire these motives in varying intensity from past experiences; they are learned responses to the feedback individuals receive from the environment as they grow to maturity. McClelland suggests that there is a tendency for some motives to be stronger than others. The degree of dominance of a given motive makes the individual tend to behave a certain way. For example, those with a high need for achievement are likely to pursue challenging tasks aggressively, would rather work than socialize, and have a tendency to want to do tasks themselves rather than delegate them to others. This contrasts with individuals who have a high need for affiliation. These people enjoy the company of others and seek it out. They do not work well on their own, preferring team tasks. Finally, people with a high power motive need to have an impact on others. They seek situations in which they can influence the actions and behavior of others. These individuals are often found in leadership positions in organizations.

Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory

Frederick Herzberg, another motivation theorist, researched the techniques managers use to motivate employees. He looked at actions taken by organizations that were intended to increase motivation by satisfying the perceived needs of employees. He found that there was a difference between factors that motivated employees to improve performance and factors that affected employee satisfaction but did not improve performance. He identified these as motivation factors and hygiene factors, respectively (Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman 1959).

Motivation Factors

Under the Herzberg theory, one group of factors functions as strong motivators and therefore can lead to better job performance; yet the absence of these factors does not cause dissatisfaction. Motivation factors include the following:

1. Achievement.

2. Recognition.

4. Pleasure in the work itself.

5. Responsibility.

From this list of motivation factors, it follows that the specific job conditions set forth below will tend to satisfy people and motivate them to greater effort, but their absence will not necessarily cause people to be less motivated.

1. Personal involvement in challenging tasks.

2. Opportunity for using abilities fully.

3. Presence of opportunities for testing one’s knowledge.

4. Discretionary control over one’s own behavior, equipment, funds, or other people.

5. Clear performance feedback.

6. Opportunity to interact with high-level executives.

The motivation factors are intrinsic to a job. Their presence tends to bring forth initiative in employees, moving them to a greater level of personal and organizational effectiveness.

Hygiene Factors

The other group of factors identified by Herzberg consists of a set of extrinsic job conditions that do not necessarily result in high job performance. When these conditions do not match expectations, however, employees are dissatisfied. Thus, managers should use these factors to provide at least a neutral atmosphere and avoid employee dissatisfaction. This set of extrinsic job conditions, which Herzberg called hygiene or maintenance factors, do not perform as motivators, but are agents of dissatisfaction when not up to expectations. They include the following:

1. Salary.

2. Job security.

3. Personal life.

4. Working conditions.

5. Status.

6. Good company policies and administration.

7. Interpersonal relations with supervisors.

8. Interpersonal relations with peers.

9. Interpersonal relations with subordinates.

10. Good technical supervision.

Accordingly, the conditions listed below tend to lead to dissatisfaction when absent from the work environment. Their presence will influence people to stay with a firm as satisfied, although not necessarily highly motivated, individuals.

1. Pleasant physical surroundings.

2. Coffee breaks and other social opportunities.

3. Good fringe benefits and salary levels.

4. Pleasant personal working relations with the supervisor, fellow employees, and others.

5. Competent supervision.

6. Promotion systems and status symbols based on seniority.

All these factors are part of the organizational climate apart from the job itself. Moreover, according to Herzberg, their presence will not motivate people to work harder than is necessary to remain employed.

Herzberg’s work has been criticized on several bases: the oversimplification of his definition of job satisfaction, his methodology, and the depth of his research. Nevertheless, the theory has had an impressive impact on management. The classification of well-established management practices into two clearly discernible groups based on their motivating effects has great appeal.

The theories of Maslow, McClelland, and Herzberg parallel each other, as shown in Exhibit 6–3. Because they help in understanding “what” motivates people, they are sometimes classified as content theories. We now examine three process theories, so-called because they help in understanding “how” people are motivated.

Expectancy Theory

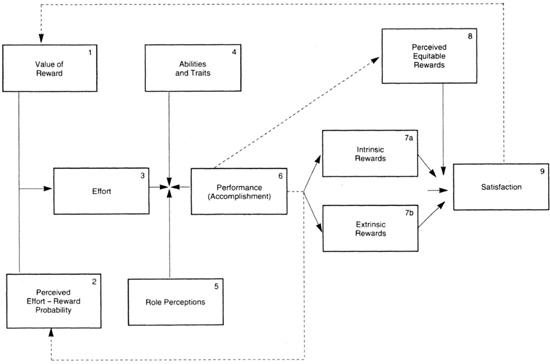

As management theorists examined the factors that influenced behavior on the job more closely, it became clear that future performance is related to the results in desired outcomes. Employees observe past actions, and the results of these past actions create expectations. Expectancy theory, diagramed in Exhibit 6–4, centers on the idea that people have expectations about the results of actions and they will act in ways to produce the results they find most desirable (Vroom 1964).

For example, a salesperson has two alternative actions to make sales: (1) wait for customers to come into the store, or (2) make calls to prospective buyers. Which action will the salesperson choose? The company has promised a promotion for salespeople who bring in new business in excess of their 15 percent goal. From past experience, the salesperson believes that calling prospects is more likely to get sales than waiting in the store. If the salesperson desires the promotion, chances are that the calling will be made. On the other hand, if a promotion would mean moving away from family and friends, the salesperson may not want it, and so would probably not make the sales calls to exceed the goal. In other words, people judge the outcomes of alternative actions. They attach value to the possible outcomes, and they act in ways that seem to produce the most desirable results for them.

Equity Theory

As noted above, behavior occurs in a context. The theories of motivation described so far explain motivation by comparing what a person has now with what the person would like to have in the future. Equity theory suggests that a component of motivation is the interpersonal comparison between individuals in similar positions in an organization (Baron 1983). It is based on the simple premise that people want to be treated fairly (Adams 1963).

Equity is defined as a ratio between a person’s job inputs (such as effort or skill) and the job rewards (such as pay or promotion) compared with the rewards others are receiving for similar job inputs. Equity theory holds that a person’s motivation, performance, and satisfaction depend on his or her subjective evaluation of the relationship between his or her effort/reward ratio to others in similar situations (Vecchio 1984). For example, if a secretary is making $20,000 a year and a new secretary is hired for $25,000 a year, a sense of inequity is virtually certain. Both sides may be motivated to remedy the inequity by acting to create a situation they feel is more fair. The $20,000-a-year secretary may feel underpaid and overworked and, in an effort to create equity in the situation, may start to produce less. The $25,000-a-year secretary may also feel the inequity and may try to work harder or take on more responsibility than the other secretary in order to compensate.

Organizational Behavior Modification

Behavioral psychology has provided managers with the basis for a theory of motivation that links rewards to behavior. Organizational behavior modification is the application of reinforcement theory to people in organizational settings (Luthans and Kreitner 1975, 1985). Reinforcement theory suggests that motivation to behave in particular ways can be increased by providing rewards for that behavior. According to this theory, positive rewards for desirable behavior will reinforce a person’s tendency to repeat that behavior. Behavior can be modified by manipulating the reward system. A manager who provides positive rewards is using the principle of operant conditioning by reinforcing desirable behavior patterns.

Reinforcement theory has provided the basis for many organizations to institute a “pay for performance” compensation system. The idea is that compensation provides a positive reinforcement for desired behavior. The concept of piecework is a good example of this system. Workers get paid for each piece that they complete, thus motivating them to produce more.

Although many successful applications of organizational behavior modification have been noted (Hamner and Hamner 1976), the motivation for human behavior is usually more complicated than this. Money does not mean the same thing to everyone, and people often are motivated by things other than compensation. The effects of the informal group and individual perceptions of value can dramatically alter the responses to managers’ efforts to motivate by reinforcement or positive, tangible rewards. Payment per piece may not be enough to ensure the quantity and quality that managers want to see. Piecework may produce the desired quantity at the expense of quality if there is no reward for quality. And even if organizational behavior modification works for a while, the impact of the positive reinforcement may wane once the novelty has worn off, and employees may come to view it as a routine part of the compensation system (Locke 1977).

MOTIVATION IN THE WORKPLACE

Motivation is individual but occurs in response to a total environment. The manager is an important part of this environment, the role of which in motivating workers to produce more was first noted as a result of the Hawthorne studies.

The Hawthorne Studies

As outlined in Chapter 2, the Hawthorne studies were scientific attempts to understand what motivated groups to different performance levels. Early in the twentieth century, some Western Electric engineers attempted to demonstrate the effect of lighting on worker productivity. The hypothesis was that if lights were dimmed, worker productivity would go down. The conditions of scientific experiment were met with an experimental room, a control room, and controlled changes. As the experimenter increased the light in the experimental room, production went up as expected. But production also rose in the control room. When the lights were dimmed in the experimental room, production went up again, and again it went up in the control room. These results surprised the researchers, because productivity was increasing in both the control room and the experimental room. They did not find a simple, direct relationship between a work condition such as lighting and increased productivity.

A significant variable was introduced by the very definition of the experiment itself. The fact that the workers were asked for their cooperation and input affected their motivation. The Hawthorne researchers concluded that worker motivation for increased productivity can be positively affected by “the organization of work teams and by the free participation of these teams in the task and purpose of the organization as it directly affects them in their daily rounds.” (Mayo 1987, 81). The results of this experiment were so startling that they have been named for the Western Electric plant at which the experiment took place. The “Hawthorne Effect” described the increased productivity that results from paying special attention to a work group.

Managers can create the Hawthorne Effect by paying special attention to their own work groups. Some have suggested that a participative decisionmaking style is likely to result in higher productivity because it simulates the conditions of the Western Electric experiments, allowing the work group to feel important.

No matter what motivational theory is applied, however, it is necessary to understand the relationship of people to work. Motivating people at work is centered on getting them to function in ways that are consistent with organizational goals. This means that people must believe that satisfying their own needs or goals is consistent with accomplishing organizational goals, or goals of their specific jobs. It also presupposes people’s approaching work with a reasonable attitude, regarding the work as a vehicle for need satisfaction. Motivating people raises questions, moreover, about the types of needs they ask to have satisfied on the job or through it, and the degree to which they naturally seek need satisfaction through work.

Theory X and Theory Y

The most widely reviewed treatise on the general approach and attitudes of people toward work was written by Douglas McGregor (McGregor 1960). McGregor presents two contrasting views of people and their relationship to work. One view, termed Theory X, is based on the following principles:

1. The average employee inherently dislikes work, will try to avoid it whenever possible, and must be coerced into performing adequately.

2. The average employee is not ambitious, dislikes job responsibilities, and prefers to be supervised closely.

3. The average employee is naturally self-centered and indifferent or oblivious to the achievement of organizational goals.

4. The average employee resists change.

5. The average employee desires job security and economic rewards above all others.

The contrasting view, termed Theory Y, is based on the following set of assumptions:

1. The expenditure of physical and mental effort in work is as natural for employees as play or rest.

2. Employees will exercise self-direction and self-control to accomplish objectives to which they are committed.

3. The commitment of employees to specific objectives is a result of the rewards associated with their achievement.

4. The average employee learns to accept rather than avoid responsibility, under proper conditions.

5. People have a substantial capacity for imagination, ingenuity, and creativity in solving organizational problems. They also want to satisfy social, esteem, and self-actualization needs. Security is important, but it is not the only consideration.

6. Most organizations only partially use the intellectual potential of the average employee.

Both Theory X and Theory Y have elements of truth. Certainly, there are individuals and work groups who can be classified easily as either Theory X or Theory Y types. Most people, however, typically fall somewhere between the two.

In the consideration of Maslow’s needs hierarchy, it was observed that all five types of basic human needs—physiological, safety, love and affection, esteem, and self-actualization—can be somewhat satisfied through work. However, if Theory X is more consistent with reality than Theory Y, management must try to motivate employees by focusing almost exclusively on the lower-order physiological and safety needs. If Theory Y holds, then management must provide opportunities for satisfying all five types of needs through employment.

Theory Z

In the late 1970s, as American managers became aware of the growing success of Japanese firms, often at the expense of American firms, they began to search for answers to their problems with productivity and the competition. They felt that if they could get their employees to produce more, they would be on the way to solving their problems. The Japanese were able to obtain high productivity from their workers. William Ouchi suggested a Theory Z, which encompassed some of the Japanese ways of thinking for an American audience (Ouchi 1981). Ouchi’s Theory Z is based on the following assumptions:

1. Employees need a sense of security; they get this by feeling as though they belong.

2. Employees who feel secure in their jobs will have a long-term identification with the company.

3. Employees will be motivated if they are included in decision making.

4. Social needs are an important part of worker identification with the workplace.

5. Needs at all levels of the Maslow hierarchy are important and should be met in the workplace.

IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS

The motivation of individuals and groups at work involves the application of all the principles stated thus far in this chapter about human behavior, the basic needs of people, and the attitudes people have about satisfying needs at work. Motivation also involves elements of interaction between management and employees. For managers, the essence of motivation is to provide an environment for employees to move voluntarily to action, with management furnishing the complementary setting of incentives and rewards. The feedback loop in Exhibit 6–5 shows a primary way managers affect employee motivation. Feedback can be either verbal or in a form of observable action.

In the remainder of this section, we identify certain management practices and behavior conducive to employee motivation.

Implications of Herzberg’s Theory

Identifying the motivation and hygiene factors and associating them with job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction in a two-factor model is one of two major contributions of Herzberg’s theory. The two-factor model implies that people require reasonable quantities of the various hygiene factors in order to prevent dissatisfaction. Once there is no particular job dissatisfaction, then the motivation factors can come into play and boost a person toward high job satisfaction.

The idea of job enrichment is the other major contribution of Herzberg’s theory. Job enrichment is essentially a motivational approach that focuses increasingly on human satisfaction and task efficiency by building greater challenge, responsibility, and opportunity for individual advancement and growth into jobs. The concept is built on the observation that although Herzberg’s hygiene, or maintenance, factors are important, they have limited effect on the quality of job performance and satisfaction. Motivation factors are those that tend to meet workers’ esteem and self-actualization needs and can be used to increase personal satisfaction and improve efficiency.

Proponents of job enrichment recognize that it can be successful only when employees have appropriate abilities and complementary psychological predispositions. Such a condition requires highly developed personnel selection. An effective performance appraisal system is also necessary for reinforcement of growth behavior.

The factors that are built into job enrichment necessarily are those that will be motivating. These include such features as people’s scheduling their own work and controlling their own job tasks and resources. Personal accountability and direct feedback also are significant aspects of job enrichment. In addition, all jobs should provide opportunities for employees to learn and to expand their skills or level of knowledge.

Job enrichment has been used successfully in many large firms, including AT&T, Texas Instruments, Travelers Insurance Company, and Motorola Corporation. At AT&T, one experiment involved employees in the stockholder relations department. Employee morale was low, turnover was high, and the work was poor. Herzberg suggested that employees be allowed to handle stockholder correspondence on their own; that is, permit the employees to do the necessary research, compose replies, and sign their own letters without having the work checked by their supervisor. The result? Turnover dropped, while productivity and morale rose dramatically.

Implications of Expectancy Theory

The research in support of expectancy theory suggests that managers control the reward system that employees use in setting their expectations. This may come from specifically stated rewards such as bonus systems or public acknowledgment of achievements. However, managers often overlook the importance of their behavior in setting expectations. Subordinates observe the actions of management very carefully and will use this information to set expectations about what will result from particular kinds of actions. For example, suppose that Sally’s manager knows that Sally has family problems and so has consistently ignored the fact that she is always late to work on Monday mornings and leaves early on Friday afternoons. Unless this situation is addressed, this manager is setting the expectation for others in the work unit that it is acceptable to be late for work on Mondays. Increased awareness of the expectations that are being set can help a manager motivate employees by creating expectations of reward for desirable behavior.

Expectancy theory also suggests that it is important to know what employees value, and to reward performance accordingly. Several other relevant guidelines are also implied for the practicing manager (Nadler and Lawler 1983):

1. Determine the primary outcomes each employee wants.

2. Decide what levels and kinds of performance are needed to meet organizational goals.

3. Make sure the desired levels of performance are possible.

4. Link desired outcomes and desired performance.

5. Analyze the situation for conflicting expectancies.

6. Make sure the rewards are large enough.

7. Make sure the overall system is equitable for everyone.

Implications of Equity Theory

Equity theory offers managers three messages (Moorhead and Griffen 1992). First, everyone in the organization needs to understand the basis for rewards. If people are to be rewarded more for high-quality work than for quantity of work, that fact needs to be clearly communicated to everyone. Second, people tend to take a multifaceted view of rewards, some tangible and others intangible. Finally, people base their actions on their perceptions of reality. If two people make exactly the same salary, but each thinks the other makes more, each will base his or her experience of equity on the perception rather than on reality. Hence, even if a manager believes two employees are being fairly rewarded, the employees themselves may not necessarily agree. A manager may hold the view that the two secretarial positions described earlier are not equal and should not be compared because the jobs are fundamentally different. However, this view will not change the perceptions of the two secretaries if they see themselves as holding comparable jobs.

Implications of Organizational Behavior Modification

Reinforcement theory has encouraged the development of incentive systems, in which managers set incentives for subordinates to reach stated goals. For example, a bonus for achieving particular sales targets is an incentive. Incentive systems may be established for achievement of individual or group goals.

Incentive systems are usually quite good at encouraging people to set goals and to meet or exceed their goals. However, a weakness of incentive systems is that in large organizations, they can often work at cross-purposes, so that incentives for one group encourage behavior that works against organizational goals. For example, offering a large incentive for individual salespeople to reach their goals may cause some “poaching”—salespeople making sales in territories that are not theirs. Additionally, any required servicing of existing contracts may be given a lower priority if servicing of accounts is not included in the incentive system. The overall effect may be intergroup competition between salespeople for territory and low-quality service after a sale has been made.

Incentive systems work well as motivational tools, but they must be developed with the entire organization in mind. They cannot provide rewards at someone else’s expense, and they must not present a potential conflict in the employees’ minds about priorities. Whether they realize it or not, managers are constantly influencing the behavior of their subordinates through the ways they withhold or offer rewards. In order to make their influence more effective, managers need to be aware of how reinforcements can best be applied (Stoner and Wankel 1986).

Perhaps the first general rule that managers should know is that what is rewarding for one individual is not necessarily so for another. For example, many employees are influenced to work longer hours by the promise of more money, but others may place higher value on time off. Another rule to keep in mind is that managers should not always accept the reasons that individuals themselves give for their actions. This is especially true when success and failure are involved. Lee Ross (1977) has described the “fundamental attribution error,” which is the tendency for people to attribute success to their own effort but failure to the actions of others or to the nature of the situation.

Managers should also be aware that some schedules of reinforcement are more effective than others. Under a continuous reinforcement schedule, the individual is immediately rewarded each time he or she manifests the desired behavior; for example, the individual is praised each time the work task is properly completed. Under a partial reinforcement schedule, rewards are provided intermittently—for example, through occasional praise for good performance and regular praise for exceptionally fine work. Continuous reinforcement has been found to lead to faster initial learning. Partial reinforcement, however, leads to a more permanent change in behavior.

W. Clay Hamner (1977) offers six rules for using organizational behavior modification techniques, pointing out that even though these rules make obvious sense, managers often violate them:

1. Don’t reward all individuals equally. To be effective behavior reinforcers, rewards should be based on performance. Rewarding everyone equally in effect reinforces poor or average performance and ignores high performance.

2. Be aware that failure to respond can also modify behavior. Managers influence their subordinates by what they do not do as well as by what they do. For example, failing to praise a deserving subordinate may cause that subordinate to perform poorly the next time.

3. Be sure to tell individuals what they can do to get reinforcement. Setting a performance standard lets individuals know what they should do to be rewarded; they can then adjust their work pattern accordingly.

4. Be sure to tell individuals what they are doing wrong. If a manager withholds rewards from a subordinate without indicating why, the subordinate may be confused about what behavior the manager finds desirable. The subordinate may also feel that he or she is being manipulated.

5. Don’t punish in front of others. Reprimanding a subordinate might sometimes be a useful way of eliminating an undesirable behavior. Public reprimand, however, humiliates the subordinate and may cause all the members of the work group to resent the manager.

6. Be fair. The consequences of a behavior should be appropriate. Subordinates should be given the rewards they deserve. Failure to reward subordinates properly or overrewarding underselling subordinates reduce the reinforcing effect of rewards.

Summary

Managers can facilitate motivation by being supportive. They can strive to understand their employees and their employees’ aspirations. They also can seek to establish desired behavior patterns and actions consistent with both organizational goals and employee needs and communicate their plans to employees. This will guide employees in goal-directed behavior and facilitate the evaluation of employee performance. The continuous use of an established system of rewards and punishments reinforces organizational guidelines and communicates their importance to employees. In this way, employees have a clear basis for assessing their behavior relative to personal needs satisfaction and organizational goals.

Do you have questions? Comments? Need clarification?

Call Educational Services at 800-225-3215, ext. 600.