7

Understanding Leadership

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Trace the development of leadership theory from trait approaches to transformational approaches.

• Diagnose situations to determine the appropriate leadership style.

• Distinguish power from authority and leadership from management.

• List and describe five bases of social power that drive effective leadership.

• Specify the significance of delegation to leadership.

In Chapter 6, we examined some theories of human motivation and noted the complexity of the subject. Based on several explanations for observed behavior in individuals, we suggested some applications of these theories for managers to use in the workplace. A basic understanding of motivation is important to managerial success, since a manager, as we discussed in Chapter 1, is a person who gets things done through other people. Many managers mistakenly view motivation strictly as a personal characteristic—some have it, others don’t. Actually, in the organizational context, this complex phenomenon is best seen as an effect resulting from the leadership of the person in charge and the situation at hand, both interacting with an individual’s personal traits.

In this chapter, we turn to the subject of leadership. In today’s turbulent times, when American managers face new challenges from global competition, strong action is needed. Many have called for new models of leadership in order for American business to meet the challenges. This chapter reviews the development of leadership theory, identifies some guidelines for leadership, and discusses the significance of effective leadership for management.

THE NATURE OF LEADERSHIP IN ORGANIZATIONS

As Ralph Stogdill (1974), a pioneer in the study of leadership, so aptly put it, “there are almost as many definitions of leadership as there are persons who have attempted to define the concept.” Few terms inspire less agreement on definition. Leadership has been defined in terms of individual traits, behavior, influence over other people, interaction patterns, role relations, occupation of an administrative position, and perception of others regarding legitimacy of influence. Definitions of leadership usually have as a common denominator the assumption that it is a group phenomenon involving the interaction between two or more persons. In addition, most definitions reflect the assumption that it involves an influence process whereby intentional influence is exerted by the leader over followers (Yukl 1989).

People have long been fascinated with the concept of leadership. Who is a leader? Why do some individuals become leaders? What characteristics do leaders share? When does an individual become identified as a leader? Is being a leader different from being a manager? These questions arise in attempts to define leadership. Many researchers have set their hands to this task, and as a result of their work, we do have some generally accepted principles of leadership (Bennis and Nanus 1985; Bradford and Cohen 1984; Yukl 1989). We will trace this search for a definition by reviewing selected contributions to understanding leadership.

Trait Approaches

If we were to develop a list of individuals considered to be great leaders, the list might include Ronald Reagan, Lee Iacocca, Pope John Paul II, Cory Aquino, Golda Meir, Mohandas Gandhi, Adolf Hitler, John F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King. Does this list help to define leadership? Although we can all generally agree that these individuals can be called leaders, we are likely to disagree about what characteristics or traits apply to them all. If we could agree on such a list of characteristics, we would have a general definition of leadership. The early trait theorists tried to do just this.

Early studies of leadership scrutinized physical traits. Leaders were found to be physically large and powerful. One review of twelve leadership studies found that leaders were taller than followers in nine instances and shorter in two.

Feldman (Time 1971, 64) found a relationship between physical traits and political leaders. He observed that except for the 1924 election of Calvin Coolidge, every presidential election from 1900 to 1968 was won by the tallest candidate. He also argued that American males under 5 feet 8 inches tall are discriminated against.

Later studies of leadership traits focused on psychological rather than physical traits. Fiedler (1960) concluded that effective leaders maintain greater psychological distance between themselves and their subordinates than less effective leaders do. The ability to provide the guidance and direction that coordinates subordinates’ efforts is a leadership skill that successful managers tend to possess and unsuccessful ones lack. Stogdill (1974, 41), in an exhaustive review of the literature, concluded that a leader is characterized by a strong drive for responsibility and task completion, vigor and persistence in pursuit of goals, venturesomeness and originality in problem solving, drive to exercise initiative in social situations, self-confidence and sense of personal identity, willingness to accept consequences of decision and action, readiness to absorb interpersonal stress, willingness to tolerate frustration and delay, ability to influence other people’s behavior, and capacity to structure social interaction systems to the purpose at hand. People who are highly flexible in adjusting their behavior in different situations are more likely to emerge as leaders in groups than are people who are less flexible (Dobbins et al. 1990). Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991) identified six traits on which leaders tend to differ from non-leaders: ambition and energy, the desire to lead, honesty and integrity, self-confidence, intelligence, and job-related knowledge. The ability to motivate people, the ability to communicate, the ability to inspire confidence in subordinates, and decisiveness frequently show up on lists of effective leader traits.

There are, however, many shortcomings in applying the trait approach. First, supporting evidence is inconsistent. One study may support the relationship between a given trait and leadership ability and another may not. For example, Stogdill (1948) refuted the contention that height was an important factor in leadership. Second, even though theorists agree on the importance of some traits, they disagree on their relative importance. Third, focusing on a leader’s traits ignores subordinates, who influence the accomplishments of the leader. Finally, the list of important leadership traits has grown continually, leaving little real understanding of leadership. Although the trait approach is still used, most leadership scholars find it unsatisfactory. Over forty-five years ago, Stogdill (1948, 35) suggested that leadership is “a process of influencing the activities of an organized group toward goal setting and goal achievement.” Stogdill made a significant contribution to leadership theory by introducing the concept of process to our understanding of leadership. Process implies a dynamic set of behaviors rather than a static set of traits.

Behavioral Approaches

Behavioral theories of leadership were pursued during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Despite Stogdill’s insight that leadership is a process of influence, researchers continued to classify leadership qualities. But instead of classifying physical or psychological traits, they looked for distinguishing behavior that could determine successful leadership.

A Leadership Continuum

Tannenbaum and Schmidt (1958, 1973) suggested that leadership styles could be seen as a continuum, based on the superior-subordinate relationship (see Exhibit 7–1). At one end of the continuum is the autocratic leader, who makes all the decisions, which subordinates are then expected to accept. Autocratic leaders exercise complete control over their followers. They not only set the goals for the group and make the final decisions, but also discourage subordinates’ participation.

At the other extreme is the democratic leader, who makes decisions jointly with nonmanagers, at least to the extent organizational constraints allow. The democratic leader allows nonmanagers to participate in the decisions on group goals and the means to achieve these goals. This style likely results in increased quality of the nonmanagement group because of their feelings of participation.

Although personally favoring the democratic style, Tannenbaum and Schmidt acknowledge that leaders need to take certain practical considerations into account before deciding on a leadership style. They suggest that a manager should consider three sets of “forces” before choosing: forces in the manager, forces in the subordinates, and forces in the situation. The continuum shows that many leadership styles can be used, representing various combinations of the two extremes. The most effective leaders will be the most flexible. They will consider their subordinates’ abilities, their own abilities, and the organization’s goals when deciding how to cope with different situations by delegating authority.

The Michigan Studies

Rensis Likert (1961) and his colleagues at the Institute of Social Research at the University of Michigan performed extensive research on leadership. They were able to identify two basic leadership styles: the job-centered leader, who concentrates on job structure, closely supervising employees to ensure that assigned tasks are completed; and the employee-centered leader, who emphasizes the human relations aspects of management and allows subordinates considerable freedom in achieving goals. Many studies were performed using these two classifications. The general conclusion Likert and his associates reached was that employee-centered managers were more effective than job-centered managers. In reaching this conclusion, Likert implied that there is no middle ground; managers are either employee-centered or job-centered. He recommended developing employee-centered managers whenever possible.

Likert’s research is extended by that of Kohn and Katz (1960). They recognized three leadership factors:

1. Closeness of supervision. Highly productive groups are not as closely supervised as less productive groups.

2. Employee orientation. Highly productive groups are allowed more participation by their superiors than less productive groups.

3. Differentiation of the supervisory role. Supervisors of highly productive groups spend less time duplicating the functions of their subordinates.

Kohn and Katz agreed with Likert that employee-centered leadership was most effective.

The Ohio State Studies

A series of empirical studies of leadership conducted by Edwin Fleishman (1955) and other scholars at Ohio State University isolated two dimensions of leadership ability: consideration and initiating structure. Consideration measures the development of mutual trust, with respect for subordinates and encouragement of two-way communication. Initiating structure measures the leaders’ ability to structure their own and subordinates’ roles in the attainment of goals.

The consideration dimension resembles the Michigan group’s employee-centered orientation. Both dimensions address individual and social needs of workers. Similarly, the initiating structure dimension is like the job-centered dimension identified by Likert and his associates. Both of these dimensions focus on issues of supervision and task accomplishment. Despite their similarities, the Michigan and Ohio State conceptions differ in an important way. As we discussed, the former sees the two dimensions of leader behavior as mutually exclusive, whereas the latter sees these dimensions as coexisting (Wagner and Hollenbeck 1992).

One of the studies by Fleishman (1955) showed a positive relationship between the proficiency of production supervisors and their initiating structure scores, while the relationship between proficiency and consideration was negative. The opposite was true of nonproduction supervisors. More recent studies have found no direct relation between leader behavior and employee reaction (Kerr et al. 1974).

The Iowa Studies

At the time of the Michigan and Ohio State studies, Kurt Lewin and his colleagues at the University of Iowa studied a leader’s manner of making decisions and identified three different decision-making styles: authoritarian, democratic, and laissez-faire. The authoritarian leader makes virtually all decisions alone. A democratic leader works with his or her group to help members come to their own decisions. The laissez-faire leader, just as the French term implies, leaves the group members alone to do whatever they want. In research settings, groups preferred democratic leaders. The Iowa studies revealed only rather modest relationships between leader style and follower behavior.

The Managerial Grid

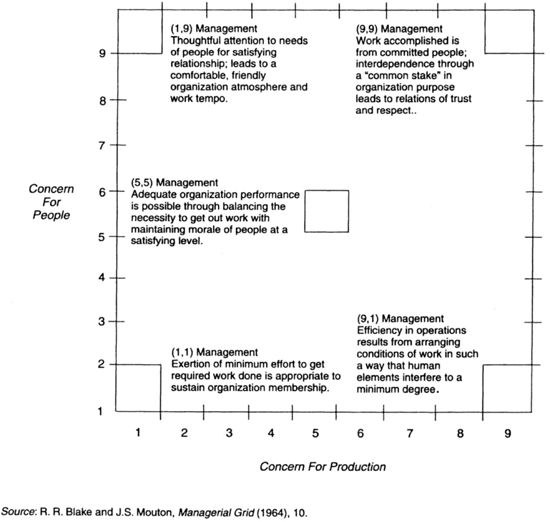

Another attempt at analyzing the relationship between two contrasting types of leaders’ behavior is Blake and Mouton’s (1964) managerial grid, republished in 1991 as the leadership grid figure (Blake and McCanse 1991). Concern for people is measured on the vertical axis; concern for production is measured on the horizontal axis (see Exhibit 7–2). Five leadership styles are identified on the grid:

• (1,1) Management. Managers at this position on the grid are weak; they show little concern for either production or people.

• (9,1) Management. Managers at this position are task-oriented. They place a high priority on output, with little or no consideration for human factors.

• (1,9) Management. Managers at this position are employee-oriented. They emphasize consideration for employees; production is secondary.

• (5,5) Management. Managers at this position are middle-of-the-road. They try to strike a balance between concern for workers and concern for production.

• (9,9) Management. Managers at this position are ideal. They try to achieve a high worker morale and a high level of output.

According to the concept, (9,9) management should be the goal of all leaders (Blake and McCanse 1991). Although the managerial/leadership grid approach has great intuitive appeal, it lacks support from rigorous empirical studies. Consideration research argues against the idea that there is any one best way of leading, irrespective of followers and situations.

Situational/Contingency Approaches

Research into leadership behavior continued to reveal contradictions. When one study suggested that a particular set of behaviors promoted effective leadership, another study found that these behaviors were not effective. No one could agree on a set of leader behaviors that would be effective for all situations. Researchers then began to examine the situations themselves. Situational theories of leadership suggest that there are elements of the situation—including the task, the subordinates, and the organization—that together act to determine the effectiveness of a given leadership style.

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory

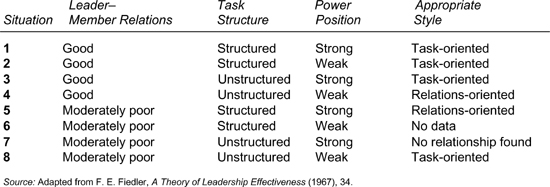

Fred Fiedler (1967) developed a contingency theory of leadership—that is, one based on a given situation. He identified three factors that determine the influence a leader derives from a particular situation:

1. Position power. This refers to the amount of influence inherent in the position. It includes the authority to reward and punish subordinates, the amount of support that the leader receives from supervisors, and the leader’s overall status within the organization.

2. Leader-member relations. This refers to the amount of trust and confidence subordinates have in the leader and to the leader’s attitude toward the subordinates.

3. Task structure. This refers to the extent to which subordinates’ jobs are clearly defined and structured.

Fiedler claimed that the appropriateness of a leader’s style to specific group situations determined the leader’s effectiveness. He analyzed various groups, such as basketball teams, military units, and management groups, and observed a pattern. Different leadership styles were more effective with different groups. Exhibit 7–3 summarizes the relationships Fiedler found. In this exhibit, eight different situations are described, varying in terms of the three key situational factors described above. For example, in Situation 1 (good relations existing between the leader and subordinates, a structured task requiring accomplishment, and strong positional power for the leader), Fiedler’s theory recommends a task-oriented leadership style.

Rather than take the approach that managers should adapt themselves to a particular style of leadership, Fiedler’s theory describes the kind of leader that best fits each situation. The proper leadership style depends on a particular situation. The leader’s power position, relationship with the group, and the task structure all determine the leadership style that will exist.

House’s Path-goal Theory

The path-goal theory of leadership derived from expectancy theory (discussed in Chapter 6) by Robert House (1971) states that effective leaders clarify the paths, or means, by which subordinates can attain both high job satisfaction and job performance. Leaders do this by clearly specifying task requirements, reducing roadblocks to task achievement, and increasing opportunities for task-related satisfaction. The leader’s function is to motivate and help subordinates reach their job-related objectives. According to the path-goal theory, it is important that the leader understand what goals and expectations subordinates have in a given situation. Once these are understood, the leader can match a leadership style to these goals.

While Fiedler’s theory assumes that a particular leader’s style is a fixed characteristic, the path-goal theory assumes that an individual has flexibility in choosing a leadership style. The choice of leadership style should rest upon the leader’s diagnosis of the task situation, as well as the employees’ expectations and goals.

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Theory

Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard (1982) have developed one of the most widely practiced models of leadership (Exhibit 7–4). They note that an element central to any leadership theory is the group being influenced—the leader’s followers. The followers actually hold the power. It is their willingness to follow that gives leaders their power.

The situational maturity of subordinates is the key variable and related to the ability and willingness of people to take responsibility for directing their own behavior. It has two components: job maturity and psychological maturity. People high in job maturity have the knowledge, skill, and experience to perform their job tasks without direction from others. People high in psychological maturity are intrinsically motivated and don’t require much external encouragement.

The maturity dimension is broken down into four stages:

M1. Subordinates are both unable and unwilling to take responsibility to do something. They are neither competent nor confident.

M2. Subordinates are unable, but willing to do the necessary job tasks. They are motivated, but currently lack the appropriate skills.

M3. Subordinates are able but unwilling to do what the leader asks of them.

M4. Subordinates are both able and willing to do what is asked of them.

Using the same two leadership dimensions as Fiedler, task and relationship behavior, situation theory then considers each as low or high and combines them into four leader styles, described as follows:

S1. Telling. The leader emphasizes directive behavior, defines roles, and tells people what, when, where, why, and how to do various tasks.

S2. Selling. The leader provides both directive behavior and supportive behavior.

S3. Participating. The leader and followers share in decision making, with the main role of the leader being facilitating and communicating.

S4. Delegating. The leader need not provide much in the way of direction and support because the subordinates neither require nor desire them.

To use the model, the manager uses a style appropriate for the maturity level of the followers (S1 to Ml, S2 to M2, etc.). Implicit in the model is the prescription that managers are supposed to do all they can to help subordinates achieve high levels of maturity.

Like the managerial/leadership grid approach, situational theory has been well received because of its intuitive appeal. However, the theory has received little attention from researchers, but on the basis of research to date, any enthusiastic endorsement should be cautioned against (Robbins 1993).

Transformational Approaches

Recent thinking about effective leadership deemphasizes theoretical complexity and looks at leadership more the way an average person might view the subject. Basically, this approach supplements situational/contingency thinking with a revival of a leader’s charisma and transformational qualities.

Transformational leaders are viewed as being charismatic and different from “ordinary” organizational leaders. Leaders of the latter type guide or motivate their followers in the direction of established goals by clarifying role and task requirements in the manner discussed prior to this section of the chapter. Transformational leaders inspire followers to transcend their own self-interests for the good of the organization and are capable of having a profound and extraordinary effect on their followers. They are proposed to have an idealized goal that they want to achieve and a strong personal commitment to their goal; they are perceived as unconventional, assertive, self-confident, and as agents of radical change rather than managers of the status quo (Conger and Kanungo 1988, 91).

Bernard M. Bass (1990, 22) describes transformational leaders as capable of providing vision and a sense of mission by instilling pride and gaining the respect and trust of followers. These leaders communicate high expectations to followers and promote intelligence, rationality, and careful problem solving. In addition, they treat each employee individually and give personal attention through coaching and advising.

Transformational leadership is used in connection with the approaches previously discussed and produces levels of subordinate effort and performance that go beyond those that might occur with a “conventional” approach alone. It is considered more than just charismatic leadership, since a purely charismatic leader may want subordinates to adopt his or her view and go no further.

Leadership and Culture

As leadership has begun to be viewed as more situationally determined and less individually determined, the situational context has become the focus of attention. The organizational context in which the process of influence or leadership takes place is also an important variable in determining leadership style. Schein (1985) suggests that leadership must be viewed within the context of organizational culture. Leaders create, maintain, and change the organizational culture; thus, leadership cannot be defined apart from the culture. Schein (1985, 2) states, “The only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage culture.” He suggests that effective leadership depends upon the individual’s ability to manage organizational culture. Thus effective leadership requires that an individual be able to diagnose organizational culture, choose appropriate leadership styles, and make changes so that the organization can adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF LEADERSHIP

The preceding survey of leadership theory shows that there has been a great deal of attention given to understanding leadership. Thinking has moved away from trait theories, to a more situational approach, and back to traits. Although the academic debate and research continues, certain characteristics of leadership are generally accepted. These include the following notions:

• Leadership is a process.

• Leadership requires the use of influence.

• Leadership requires the power to influence.

• Leadership is group dependent.

• Leadership is dynamic.

As stated in the review of leadership theories, leadership is a process of influence rather than a set of characteristics (Stogdill 1948). According to this perspective, leaders share behavior rather than traits, and all leaders share an ability to influence a group.

Leadership requires the use of influence, which can be defined as any act or potential act that affects the behavior of another person (Cohen et al. 1984, 266). Later in this chapter, we explain how individuals are able to influence groups. Essentially, leadership requires a base of social power, a situation, a task, and a group congruent with the preferred style of the individual leader.

Leadership is also group dependent—it exists only because the group exists. The process of influence requires that one or more other individuals be present to engage in an interaction. It is possible to engage in influencing behavior only if one is in the presence of another. A leader in one situation may become a follower if the circumstances change dramatically enough to cause another leader to emerge. For example, a guide may be leading a group through a tour of the White House. As long as the situation remains the same, the tour guide will command the group’s attention and following. However, if smoke suddenly begins billowing up a hall from behind the group and a group member shouts, “Fire!” and then, “Follow me!” chances are that the group will follow that individual. Leadership of the group would change from the tour guide to the speaker of the command. The quick reaction and apparent expertise of the person saying, “Follow me!” make that person the new leader of that group for that particular situation.

Finally, leadership is dynamic because, as George Labovitz has stated (1985, V-7), “In a real sense it is a contract between an individual and the group and is in a continuous state of renegotiation.” An individual’s status as leader is dependent upon the group’s response. This response is constantly in a state of change; thus, leaders must constantly renegotiate their status.

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

Consider the concept of leadership as it relates to management. In thinking of a list of leaders, how many managers would you include on that list? Are all managers leaders? Are all leaders managers? The answer to both of these questions is not all, but certainly some. The key distinction between being a manager and being a leader lies in the distinction between power and authority.

Authority can be defined as the right to give orders, a right vested in a position and not a person. As Fayol noted (1949), if individuals are given authority, they must be held responsible for the results of using that authority. In contrast, power can be defined as the ability to influence people. This influence can be derived from authority, but need not be. An informal leader, for example, has power, but may not have authority.

As noted earlier, leadership is a process of influencing a group toward common objectives. Influence stems from power. Power is different from authority: Authority is bestowed by the organization, but power has different sources. Where does power come from?

French and Raven (1959) have identified five sources of power:

1. Legitimate power (sometimes called bureaucratic authority). This power comes from having a superior status in the organizational framework. It is the basis for authority, as described above. Legitimate power is most effective if the employees accept the leader. If not reinforced by other sources of power, it is less influential.

2. Reward power. This involves providing positive reinforcement. A leader uses a positive reward, either monetary (a raise in pay) or psychological (a compliment). Reward power is available to most managers. For it to be effective, however, there must be a direct and observable relationship between accomplishing group objectives and receiving the reward. It is not unusual for a work group to attempt to negate reward power by punishing those workers who respond to it. For example, a group may refuse to socialize with a worker who it feels is working too fast, thus making the other workers look slow or lazy. This is especially true if the workers are paid a piece rate and are in danger of having production standards increased because of the faster worker.

3. Coercive power (sometimes called dominance). This type of power is based on fear, either physical or psychological. In a business setting, this usually takes the form of a fear of being fired or of receiving an undesirable work assignment. In most work situations in our society, coercive power should be used sparingly and only as a last resort; its frequent use alienates a work group.

4. Expert power This power resides in people who have some special knowledge or expertise that enables them to gain the respect and cooperation of the group. Ideally, managers have enough expertise to command this sort of power. To the extent that the manager depends on another person for expertise, that other person shares some of the manager’s power.

5. Referent power. This type of power is based on the subordinates’ identification with the leader. Followers are influenced by their regard for a given leader. The leader may not necessarily be liked, but is respected.

These five sources of power can be classified into two main categories: organizational and personal. Coercive, reward, and legitimate power stem directly from status within the organization. Generally, the higher the position a person holds in the organizational hierarchy, the greater the amount of each of these kinds of power he or she possesses. On the other hand, expert and referent power depend primarily on individual characteristics, the group’s characteristics, and the requirements of the task.

From these conclusions come certain implications for managers. First of all, some sources of influence overlap. For example, reward and legitimate power often go hand in hand, and referent and expert power are also frequently related. Second, the more numerous the sources of a leader’s power, the greater his or her effectiveness.

Understanding these different sources of power helps us to distinguish between managers who are not leaders and those who are. A true leader will possess and use most, if not all, of the five sources of power, while the manager who is less of a leader will rely on the three sources bestowed by virtue of his or her position in the organization: legitimate, reward, and coercive power.

Do all managers have to be leaders? No. Bradford and Cohen (1984) suggest using the terms interchangeably, with a focus on the managerial aspects of the position. They suggest that our models of leaders are overly rooted in the concept of “heroic management.” This type of manager tends to burn out more quickly, in addition to being less effective than a manager who is more of a developer. In addition, Bradford and Cohen contend that if too much attention is focused on being a leader, ultimate business goals may get lost. The developer-manager, on the other hand, diagnoses the situation, the task, and the group more appropriately and uses others as leaders if necessary in order to achieve the strategic objective of the company.

American heroes have tended to be tough people who do it alone—who carry the burden of a big job on their shoulders. These ideals have carried over into the world of management, creating a widely held perception that the good manager or leader should reflect these characteristics. However, as Bradford and Cohen have noted, the heroic style of doing it alone is not the most effective way of managing. In fact, effective management requires making the most of the resources available; and, as noted in Chapter 5, the most valuable resource a business has is its people.

Developer-managers see their role not as heroic leaders, but as coaches. A coach is one who can assist subordinates in developing their own talents, in taking on greater challenges, and in striving for quality. This is a difficult task for many managers because it may mean developing others as leaders. In order to do this, managers must rise above the notion that there can be only one leader, and that that one leader must be the boss. If all managers could develop the potential of their subordinates, American businesses could achieve tremendous gains from the additional resources that would then be at their disposal.

DELEGATION

Delegation is the process by which managers assign formal authority, responsibility, and accountability for work activities to subordinates. Thus, delegation is an integral part of the process of leadership. The importance of effective delegation was underscored by Lyndall Urwick (1944, 51), a pioneering management scholar, who observed, “Without delegation, no organization can function effectively. Yet, lack of courage to delegate properly and of knowledge of how to do it is one of the most general causes of failures in organizations.”

In the delegation process, legitimate power is conferred on subordinates, as well as reward power and coercive power to some extent. Expert power may also be conveyed indirectly in that the subordinate who now acts in place of the superior will acquire expert power to the extent he or she develops the necessary skills to perform the tasks. To some extent delegation is thus empowerment. The extent to which managers delegate is influenced by factors such as the culture of the organization, the specific situation involved, and the relationships, personalities, and capabilities of those involved.

Louis Allen (1981) has listed six useful delegation principles that apply to most situations:

1. Establish objectives and standards. Subordinates should participate in developing the objectives they are expected to meet. They should also agree to the standards that will measure their performance.

2. Define authority and responsibility. Subordinates should clearly understand the work and authority delegated to them, recognize their responsibility, and accept their accountability for results.

3. Involve subordinates. The challenge of the work itself will not always encourage subordinates to accept and perform delegated tasks well. Managers can motivate subordinates by involving them in decision making, by keeping them informed, and by helping them improve their skills and abilities.

4. Require completed work. Managers should require subordinates to carry work through to completion. The manager’s job is to provide guidance, help, and information.

5. Provide training. Delegation can be only as effective as the ability of people to perform the work and make the necessary decisions. Managers should continually appraise delegated responsibilities and provide training programs aimed at building on strengths and overcoming deficiencies.

6. Establish adequate controls. Managers should provide timely, accurate reports that enable subordinates to compare their performance to agreed-on standards and to correct their deficiencies.

IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS

None of the various leadership approaches discussed in this chapter (nor those omitted from discussion) provide all that is needed for a manager to be an effective leader. Every approach has shortcomings. Viewed broadly, however, there are a number of observations that can serve as guides for managers as they seek to become competent leaders.

Undoubtedly, there is no list of traits that universally defines successful leaders. However, in a wide variety of organizational situations, a number of characteristics tend to distinguish leaders from nonleaders and effective from ineffective leaders. To the extent managers possess, or develop, characteristics such as those discussed in this chapter, the more likely they will be able to influence their subordinates in desirable ways.

Research strongly indicates that leader behaviors broadly classified as task-centeredness and people-centeredness are important dimensions for managerial effectiveness. Task-centered leaders have also been described as autocratic, restrictive, directive, structuring, socially distant, task-oriented, and close (in the sense of close versus general supervision). People-centered leaders have been labeled democratic, participative, permissive, relation-centered, people-oriented, and follower-oriented.

Stogdill (1974, 403-407) has examined the effects of both of these types of leader behavior on the important managerial concerns of group productivity, job satisfaction, and group cohesiveness. More often than not, task-centered behavior relates positively with productivity, whereas being people-centered has no consistent relationship. There is no assurance that group productivity can be increased simply by the leader being more people-centered. Being socially distant (in the sense of defining the leader’s role as separate and distinct from that of subordinates), directive, and structuring (in the sense of communicating to subordinates what is expected of them) tends to be associated with productivity. Being autocratic and restrictive tends to be inconsistently related or unrelated to productivity.

Being people-centered does tend to enhance employee satisfaction and group cohesiveness, but being task-centered, with the exception of engaging in structuring behavior, tends to do the opposite. Structuring behavior tends to enhance satisfaction and cohesiveness. These observations are consistent with the prescription of Blake and McCanse for (9,9) management (1991); that is, leaders should engage in high levels of both people-centered and task-centered behavior, with structuring work activities being the focus of the task-centered behavior.

According to House’s path-goal theory (1971), a leader’s major function is to provide a path for increasing subordinates’ job satisfaction and productivity. This is done by clarifying the nature of the task, increasing opportunities for job satisfaction, and fostering conditions that help employees complete their tasks. Simply put, managers should find out what their people want and help them get it.

The situational theory of Hersey and Blanchard (1982) takes the two leadership dimensions discussed above a step further by specifying for the leader (through the use of Exhibit 7–4) the relative degree of task and relationship behavior necessary in relation to the relative job and psychological maturity of the individual or group.

In most organizations, people first become managers because of a promotion based primarily on technical competence. Charismatic and transformational qualities are considered infrequently, if at all. It follows, therefore, that these qualities are not widely present among those in organizations responsible for leading others. Indeed, these qualities are viewed as inherent to an individual and relatively uncommon. It is possible, however, for a manager to develop transformational qualities by communicating high expectations to subordinates by word and action, doing everything possible to instill pride of accomplishment in subordinates, and intensely promoting subordinates’ self-interests through conscientious coaching and advising.

Summary

To be effective leaders, at minimum, managers need to establish their roles as separate and distinct from those of their subordinates, and they need to be proficient in job-related knowledge and skills. Proficiency does not mean that the manager must necessarily be the “best” or “know it all” under all circumstances.

Managers should be capable of engaging in high levels of both task- and people-centered behaviors, varying these behaviors in relation to the situational maturity of subordinates. They need to communicate what is expected of subordinates by clarifying the nature of tasks, letting subordinates know how well they are doing, and what might need to be done to improve performance. As the situation warrants, managers should engage in delegation. In order for any delegation to be effective, managers need to do all they can to help subordinates achieve situational maturity.

Above all, the more effective managers will be flexible. They will embrace all five sources of organizational power, relying most heavily on expert and referent power, while judiciously using legitimate, reward, and coercive power as the situation dictates.

Finally, to the degree that it is within their personal makeup, the more effective leaders will convey a vision to subordinates of how work-related conditions can be improved in the future and a sense of mission in carrying out the improvements. The effective leaders do this by being assertive and self-confident and working diligently to gain subordinates’ respect and trust.

Do you have questions? Comments? Need clarification?

Call Educational Services at 800-225-3215, ext. 600.